Abstract

A comprehensive understanding of the native pulmonary blood supply is crucial in newborns with pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect and aortopulmonary collaterals (PA/VSD/MAPCA). We sought to describe the accuracy in terms of identifying native pulmonary arteries, radiation dose and anaesthetic time associated with multi-modality imaging in these patients, prior to their first therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, we wanted to evaluate the cumulative radiations dose and anaesthetic time over the study period. Patients with PA/VSD/MAPCA diagnosed at < 100 days between 2004 and 2014 were identified. Cumulative radiation dose and anaesthetic times were calculated, with imaging results compared with intraoperative findings. We then calculated the cumulative risks to date for all surviving children. Of 19 eligible patients, 2 had echocardiography only prior to first intervention. The remaining 17 patients underwent 13 MRIs, 4 CT scans and 13 cardiac catheterization procedures. The mean radiation dose was 169 mGy cm2 (47–461 mGy cm2), and mean anaesthetic time was 111 min (33–185 min). 3 children had MRI only with no radiation exposure, and one child had CT only with no anaesthetic. Early cross-sectional imaging allowed for delayed catheterisation, but without significantly reducing radiation burden or anaesthetic time. The maximum cumulative radiation dose was 8022 mGy cm2 in a 6-year-old patient and 1263 min of anaesthetic at 5 years. There is the potential to generate very high radiation doses and anaesthetic times from diagnostic imaging alone in these patients. As survival continues to improve in many congenital heart defects, the important risks of serial diagnostic imaging must be considered when planning long-term management.

Keywords: Pulmonary atresia, Aortopulmonary collaterals, Imaging modalities, Radiation, Anesthetic time

Introduction

Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect represents a spectrum of congenital heart disease with significant anatomical heterogeneity. In patients where the pulmonary blood supply is provided by aortopulmonary collaterals(PA/VSD/MAPCA), accurate imaging is critical to long term planning and prognosis; in particular, the presence of absence of native pulmonary arteries [1, 2]. In view of this, multiple imaging modalities may be employed in the same patient even before any intervention is performed, all of which can carry important risks (Table 1) [3–9]. General anaesthesia, for example, almost universally required under 6 months of age, carries significant risks in patients with single ventricle physiology (such as pulmonary atresia) in this age group [10–13]. The use of ionising radiation associated with CT and cardiac catheterisation also carries important long-term risks, with younger children 3 to 4 times more likely than adults to develop malignancies following radiation exposure [3, 14–16]. Cardiac catheterisation alone accounts for by far the largest proportion of radiation exposure in children with congenital heart disease [3, 17, 18].

Table 1.

Imaging modalities in patients with pulmonary atresia

| Modality | Advantages | Disadvantages/risks |

|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography |

Bedside test Non-invasive |

Poor visualisation of most extrapericardial structures |

| Cardiac catheterisation [4, 5, 8] |

Can determine dual supply of lung segments Direct pressure measurements Accurate in identifying native pulmonary arteries |

Invasive Risk of vascular injury, stroke, death General anaesthetic required Radiation risk |

| CT Angiography [4, 6, 7] |

Fast acquisition Accurate for native pulmonary arteries, shunts and vessel sizes Can image extracardiac structures |

General anaesthetic likely to be required Radiation risk |

| MRI Angiography [6, 8, 9] |

Relatively accurate for pulmonary arteries and larger collaterals Can calculate flow rates Can image extracardiac structures No radiation |

General anaesthetic likely to be required Less accurate than CT for sub-millimetre vessels Slow acquisition time Possible gadolinium deposition in the brain |

The aim of this study was to quantify the radiation exposure and anaesthetic time associated solely with diagnostic imaging to identify native pulmonary arteries, if present, in newborns and infants with PA/VSD/MAPCA, prior to their first therapeutic intervention. We then calculated the cumulative risks to date for all surviving children.

Materials and Methods

The institutional database of the Department of Congenital Heart Disease (Heartsuite, Systeria, Glasgow, United Kingdom), at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital in London, United Kingdom, was interrogated to find all patients diagnosed with pulmonary atresia, ventricular septal defect and aortopulmonary collaterals under 100 days of age, between 2004 and 2014. The cumulative radiation doses and anaesthetic time of patients during the study period was calculated. Radiation doses are given in dose area product units (cGy cm2) [16], which are independent of the location of measurement and regarded as being suitable for describing radiation exposure in children [19].

In keeping with unit policy, decision making for these complex patients was not protocolised over this time period, and imaging strategies were determined on a case-by-case basis; hence, not every patient underwent all imaging modalities. We also evaluated the cumulative radiation dose and anaesthetic time for these patients over the whole study period.

Results

19 patients diagnosed with PA/VSD/MAPCA under the age of 100 days were identified. The first investigation was transthoracic echocardiography in all cases, of which 17 patients went on to have further imaging. In total, there were 13 MRI scans, 13 cardiac catheterisations and 4 CT scans performed in this group before therapeutic intervention. All were within the first 100 days of life, and aside from one patient with 2 MRI scans, no patient had the same investigation more than once. A full summary of the imaging strategy used in each patient is depicted in Table 2, including the accuracy of the imaging modalities in identifying the presence of native pulmonary arteries. Example imaging from a single patient is shown Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Imaging strategy, additional findings and cumulative radiation dose and anaesthetic time prior to first intervention

| Age (d) | PAs on echo? | Imaging 1 | Age (d) | PAs? | Imaging 2 | Age (d) | PAs? | Other findings | Imaging 3 | Age (d) | PAs? | Other findings | PAs at Surgery? | GA (mins) | Rad (mGy cm2) | Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 0 | 0 | Shunt to PAs |

| 2 | 0 | Yes | Cath | 6 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 181 | 78 | Shunt to PAs |

| 3 | 1 | No | MRI | 5 | No | MRI | 79 | No | + 1 APC | Cath | 86 | No | None | No | 90 | 141 | Shunt to unif. |

| 4 | 0 | Yes | MRI | 4 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 92 | 0 | Shunt to PAs |

| 5 | 0 | Yes | MRI | 5 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 33 | 0 | Shunt to PAs |

| 6 | 0 | No | Cath | 1 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 40 | 62 | Shunt to PAs |

| 7 | 0 | Yes | MRI | 2 | Yes | Cath | 16 | Yes | None | – | – | – | – | Yes | 114 | 231 | Shunt to PAs |

| 8 | 0 | Yes | MRI | 19 | Yes | Cath | 34 | Yes | None | – | – | – | – | Yes | 185 | 172 | Shunt to PAs |

| 9 | 0 | Yes | Cath | 2 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 108 | 122 | Shunt to PAs |

| 10 | 0 | Yes | MRI | 11 | No | Cath | 34 | Yes | None | – | – | – | – | Yes | 91 | 58 | Shunt to PAs |

| 11 | 94 | Yes | MRI | 96 | No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | No | 52 | 0 | Shunt to unif. |

| 12 | 1 | No | MRI | 6 | No | Cath | 8 | Yes | + 1 APC | – | – | – | – | Yes | 107 | 158 | Shunt to PAs |

| 13 | 73 | Yes | MRI | 76 | Yes | Cath | 80 | Yes | + 1 APC | – | – | – | – | Yes | 118 | 47 | Shunt to PAs |

| 14 | 11 | Yes | MRI | 18 | No | Cath | 60 | No | None | CT | 85 | Yes | None | No | 157 | 461 | Shunt to unif. |

| 15 | 10 | Yes | MRI | 11 | No | Cath | 17 | Yes | + 1 APC | – | – | – | – | Yes | 174 | 338 | Stent to PDA |

| 16 | 0 | Yes | CT | 1 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 0 | 66 | Shunt to PAs |

| 17 | 0 | Yes | MRI | 1 | No | CT | 7 | No | + 2 APCs | Cath | 13 | Yes | − 1 APC | Yes | 130 | 191 | Shunt to PAs |

| 18 | 23 | No | CT | 24 | No | Cath | 25 | Yes | PAs | – | – | – | – | Yes | 108 | 238 | Conduit to unif. |

| 19 | 0 | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Yes | 0 | 0 | Shunt to PAs |

PAs pulmonary arteries, GA general anaesthetic, Rad radiation dose, Cath catheterisation, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, APC aortopulmonary collaterals, Unif unifocalised collaterals, CT computed tomography, PDA patent arterial duct

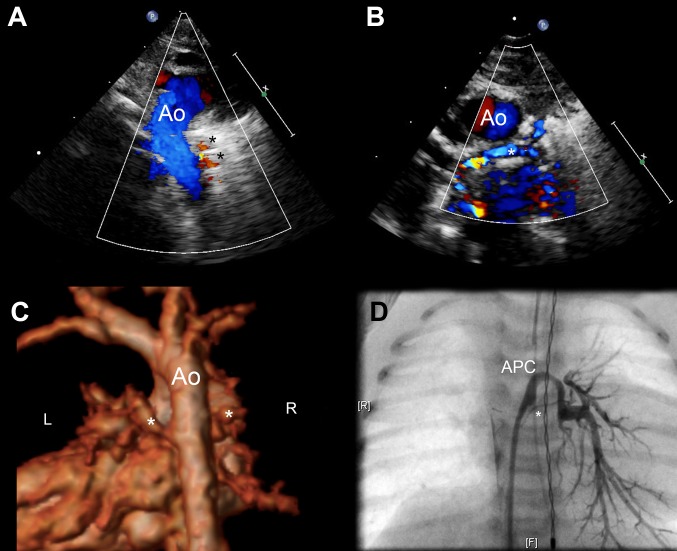

Fig. 1.

a Echocardiography immediately after birth in a patient antenatally diagnosed with pulmonary atresia and ventricular septal defect showing a right sided aortic arch and collateral vessels (asterisked) arising from the descending aorta. Ao aorta. b Parasternal short axis view from the same study showing suspected confluent, but severely hypoplastic pulmonary arteries (asterisked). Ao aorta. c 3D reconstructed MRI on day 1 of life in the same patient, clearly demonstrating large collaterals to the left and right lung from the descending aorta. The possibility of a small native left pulmonary artery was raised but the study was not conclusive. CT imaging was subsequently performed at 7 days—no native pulmonary arteries were identified. d Still from aortic injection during cardiac catheterisation on day 13 of life. Tiny confluent branch pulmonary arteries were identified (asterisked), in addition to the major collaterals previous described

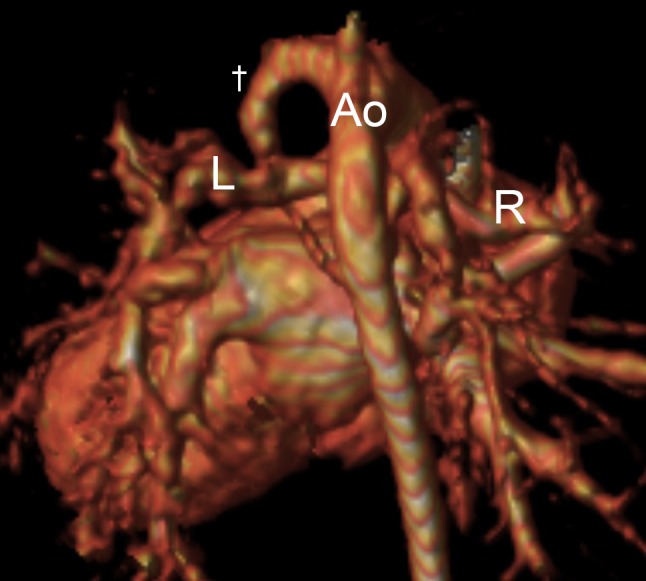

Fig. 2.

3D reconstructed MRI at 9 months of age, following the insertion of a left-sided Blalock-Taussig shunt (†) at 34 days of age. The right (R) and left (L) pulmonary arteries are now clearly visible. Prior to intervention, the patient had received a total of 120 min of general anaesthetic time and a radiation dose of 191 mGy m2. Ao aorta

The mean cumulative anaesthetic time for all forms of imaging was 111 min (median 108 min, range 33–185 min). One child who underwent CT only after echocardiographic evaluation did not have general anaesthetic. The mean radiation dose for the 13 patients undergoing diagnostic cardiac catheterisation was 119 mGy cm2 (median 122 mGy cm2, range 47–231 mGy cm2). In the four patients who underwent CT, the mean radiation dose was 92 mGy cm2 (median 90 mGy cm2, range 66–123 mGy cm2). The mean total radiation dose for the three patients undergoing both catheterisation and CT was 297 mGy cm2 (median 238 mGy cm2, range 191–461 mGy cm2). A total five patients (two with echo only and three echo and MRI only) had no radiation exposure prior to therapeutic intervention.

The average age of patients undergoing primary cardiac catheterisation was 3 days (median 2 days, range 1–6 days, n = 3). For patients undergoing primary CT or MRI, the mean age of any subsequent catheterisation (n = 10) was 35 days (median 21 days, range 8–86 days; p = 0.09). Having an MRI or CT prior to catheterisation did not significantly reduce the radiation dose or anaesthetic time of the cardiac catheterisation in our series.

Over the 10-year period of our study, many surviving patients underwent further imaging to assess the pulmonary vasculature. This comprised of non-invasive cross-sectional imaging as well as diagnostic and/or interventional cardiac catheterisation, most frequently to address circumferential stenosis in the reconstructed pulmonary arteries. Table 3 shows the cumulative number of investigations performed to date, including the total number of X-ray radiological studies, with total radiation dose and anaesthetic times for each patient.

Table 3.

Lifetime imaging, cumulative radiation dose and anaesthetic time

| N | Age at last follow up |

N

Cath |

Cath Rad (mGy cm2) | Cath GA (mins) |

N

CT |

CT Rad (mGy cm2) |

N

MRI |

MRI GA (mins) |

N

CXR |

N

OXR |

Total Rada (mGy cm2) | Total GA (mins) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 years | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 172 | 18 | 34 | 0 | 172 |

| 2 | 8 years | 3 | 2843 | 409 | – | – | 2 | 186 | 34 | – | 2843 | 595 |

| 3 | d. 96 days | 1 | 141 | 63 | – | – | 2 | 57 | 6 | – | 141 | 120 |

| 4 | 5 years | 5 | 4327 | 811 | 1 | 34 | 4 | 452 | 30 | 6 | 4361 | 1263 |

| 5 | d. 17 months | 2 | 1156 | 170 | – | – | 2 | 96 | 26 | 1 | 1156 | 266 |

| 6 | 3 years | 2 | 185 | 125 | – | – | 2 | 131 | 25 | 1 | 185 | 256 |

| 7 | d. 32 days | 1 | 231 | 100 | – | – | 1 | 14 | 16 | 2 | 231 | 114 |

| 8 | 2 years | 1 | 172 | 98 | – | – | 2 | 147 | 15 | – | 172 | 245 |

| 9 | 6 years | 5 | 8022 | 786 | – | – | 3 | 358 | 39 | 1 | 8022 | 1144 |

| 10 | 5 years | 3 | 1357 | 245 | – | – | 3 | 199 | 45 | 12 | 1357 | 444 |

| 11 | 5 years | 2 | 104 | 155 | 1 | 133 | 1 | 52 | 57 | 14 | 237 | 207 |

| 12 | d. 18 months | 2 | 1409 | 164 | – | – | 2 | 114 | 15 | 1 | 1409 | 278 |

| 13 | 4 years | 1 | 47 | 56 | – | – | 2 | 134 | 23 | – | 47 | 190 |

| 14 | d. 2 years | 1 | 338 | 108 | 1 | 123 | 2 | 145 | 42 | 4 | 461 | 253 |

| 15 | d. 30 days | 1 | 804 | 110 | – | – | 1 | 64 | 12 | – | 804 | 174 |

| 16 | 16 months | 2 | 349 | 237 | 2 | 404 | 1 | 28 | 26 | 3 | 753 | 265 |

| 17 | 9 months | 1 | 84 | 119 | 1 | 107 | 1 | 11 | 20 | 7 | 191 | 130 |

| 18 | 10 months | 1 | 165 | 108 | 2 | 303 | – | – | 42 | 4 | 468 | 108 |

| 19 | d. 31 days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

N number, Cath catheterisation, Rad radiation dose, CT computed tomography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, GA general anaesthetic, CXR chest X-ray, OXR other X-ray, d. died

aNot including radiation from chest and other X-rays

Discussion

We have attempted to quantify the cumulative anaesthetic time and radiation exposure resulting from serial diagnostic investigations in patients with PA/VSD/MAPCA. The median radiation dose in our series prior to intervention was 122 mGy cm2, with one patient undergoing 157 min of general anaesthetic time and a total radiation dose of 461 mGy cm2 within the first 3 months of life, prior to any therapeutic intervention being performed. By way of comparison, the median radiation dose for 312 interventional catheter procedures in our institution—across all age groups—was 176 mGy cm2 from 2005 to 2009 [16]. We rarely perform pure diagnostic catheterisation in our institution, and hence could not compare to diagnostic catheterisations for other reasons.

As anticipated, despite carrying the highest risks, cardiac catheterisation appeared to be the “gold standard” investigation, correctly identifying the presence or absence of native pulmonary arteries in all patients. It was also most frequently the final investigation before committing to intervention. MRI and CT showed poorer sensitivity to identify native pulmonary arteries in our patients, and whilst the numbers were too small to allow for a comprehensive comparison, falling acquisition times and the use of CT and MRI imaging without anaesthesia continue to increase their attractiveness in a clinical setting [6, 20, 21]. CT in particular has shown promising results for infants with aortopulmonary collaterals [22], with the potential for a reduced radiation burden in modern systems [23]. The potential advantage of cross-sectional imaging providing an initial “roadmap” for subsequent catheterisation was, however, not clearly demonstrated in our series: the mean radiation dose when catheterisation was performed without prior CT/MRI was 87 mGy cm2 (median 78 mGy cm2, range 62–122 mGy cm2, n = 3), and 152 mGy cm2 (median 150 mGy cm2, 47–338 mGy cm2, n = 10) when cross-sectional imaging was available; the mean anaesthetic time was 110 min (median 108 min, range 40–181 min) versus 86 min (median 99 min, range 40–119 min), respectively (p = 0.38). In both MRI and CT settings, correct imaging of vessels is flow dependent, and in cardiac catheterisation usually injections of contrast is done with “power injections” per pump or by hand, hence providing adequate flow locally [24].

Repeated diagnostic and interventional procedures in patients with PA/VSD/MAPCA, in particular cardiac catheterisation, can lead to extremely high cumulative radiation doses in later childhood. Children are more susceptible than adults to the effects of ionising radiation and, as survival continues to improve, these patients will have a longer life-span over which that risk is expressed [16, 25]. One patient of our series has been exposed to a cumulative radiation dose of 8022 mGy/cm2 at the age of 6 years, from five catheterisation procedures. One could argue that such radiation dose moves the future malignancy risk from stochastic towards probable, even when taking into account anticipated life expectancy [25].

Limitations

This is a single centre, retrospective, descriptive study. During the study period, no protocol regarding imaging to identify native pulmonary arteries existed in our institution, and different imaging modalities were applied on a case-to-case basis.

Conclusion

Whilst optimisation of the pulmonary circulation is crucial in patients with PA/VSD/MAPCA, there is the potential to generate very high radiation doses and anaesthetic times from diagnostic imaging alone. As survival continues to improve in patients with a range of complex congenital heart defects, the important risks of serial diagnostic imaging must be considered alongside long-term interventional strategies.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

The institutional audit board waived the need for informed consent for this retrospective data analysis.

References

- 1.Griselli M, McGuirk SP, Winlaw DS, et al. The influence of pulmonary artery morphology on the results of operations for major aortopulmonary collateral arteries and complex congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metras D, Chetaille P, Kreitmann B, Fraisse A, Ghez O, Riberi A. Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, extremely hypoplastic pulmonary arteries, major aorto-pulmonary collaterals. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:590–596. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(01)00855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JN, Hornik CP, Li JS, Benjamin DK, Jr, et al. Cumulative radiation exposure and cancer risk estimation in children with heart disease. Circulation. 2014;130:161–167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greil GF, Schoebinger M, Kuettner A, et al. Imaging of aortopulmonary collateral arteries with high-resolution multidetector CT. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:502–509. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ley S, Zaporozhan J, Arnold R, et al. Preoperative assessment and follow-up of congenital abnormalities of the pulmonary arteries using CT and MRI. Eur Radiol. 2006;17:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor AM. Cardiac imaging: MR or CT? Which to use when. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:433–438. doi: 10.1007/s00247-008-0843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollingsworth CL, Yoshizumi TT, Frush DP, et al. Pediatric cardiac-gated CT angiography: assessment of radiation dose. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;189:12–18. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romeih S, Al-Sheshtawy F, Salama M, et al. Comparison of contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography with invasive cardiac catheterisation for evaluation of children with pulmonary atresia. Heart Int. 2012;7:e9. doi: 10.4081/hi.2012.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao UV, Vanajakshamma V, Rajasekhar D, Lakshmi AY, Reddy RN. Magnetic resonance angiography vs. angiography in tetralogy of Fallot. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2013;21:418–425. doi: 10.1177/0218492312457360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sümpelmann R, Osthaus WA. The pediatric cardiac patient presenting for noncardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20:216–220. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3280c60c89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottlieb EA, Andropoulos DB. Anesthesia for the patient with congenital heart disease presenting for noncardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26:318–326. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328360c50b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odegard KC, DiNardo JA, Kussman BD, et al. The frequency of anesthesia-related cardiac arrests in patients with congenital heart disease undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:335. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000268498.68620.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramamoorthy C, Haberkern CM, Bhananker SM, et al. Anesthesia-related cardiac arrest in children with heart disease: data from the pediatric perioperative cardiac arrest (POCA) registry. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1376–1382. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181c9f927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee to Assess Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation, Nuclear and Radiation Studies Board, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council of the National Academies . Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation BEIR VII phase. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Williams A, et al. The use of computed tomography in pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:700–707. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith BG, Tibby SM, Qureshi SA, Rosenthal E, Krasemann T. Quantification of temporal, procedural, and hardware-related factors influencing radiation exposure during pediatric cardiac catheterisation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80:931–936. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downing TE, McDonnell A, Zhu X, et al. Cumulative medical radiation exposure throughout staged palliation of single ventricle congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;36:190–195. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-0984-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan Frandics P., Hanneman Kate. Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Neonates With Congenital Cardiovascular Disease. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 2015;36(2):146–160. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boothroyd A, McDonald E, Moores BM, Sluming V, Carty H. Radiation exposure to children during cardiac catheterisation. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:180–185. doi: 10.1259/bjr.70.830.9135445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fogel MA, Weinberg PM, Parave E, et al. Deep sedation for cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a comparison with cardiac anesthesia. J Pediatr. 2008;152:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards AD, Arthurs OJ. Paediatric MRI under sedation: is it necessary? What is the evidence for the alternatives? Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:1353–1364. doi: 10.1007/s00247-011-2147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meinel FG, Huda W, Schoepf UJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of CT angiography in infants with tetralogy of fallot with pulmonary atresia and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2013;7:367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou QR, Gao W, Sun AM, et al. A prospective evaluation of contrast and radiation dose and image quality in cardiac CT in children with complex congenital heart disease using low-concentration iodinated contrast agent and low tube voltage and current. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:20160669. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valverde I, Parish V, Hussain T, et al. Planning of catheter interventions for pulmonary artery stenosis: improved measurement agreement with magnetic resonance angiography using identical angulations. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77(3):400–408. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harbron R, Chapple C-L, O’Sullivan JJ, Best KE, Berrington de González A, Pearce MS. Survival adjusted cancer risks attributable to radiation exposure from cardiac catheterisations in children. Heart. 2017;103:341–346. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]