Abstract

Purpose

In this study, we elucidated the effects of berberine, a major alkaloid component contained in medicinal herbs, such as Phellodendri Cortex and Coptidis Rhizoma, on expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) in a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line (ARPE-19) caused by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation.

Methods

ARPE-19 cells were cultured to confluence. Berberine and LPS were added to the medium. MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA were measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction. MCP-1 and IL-8 protein concentrations in the media were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

After stimulation with LPS, MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA in ARPE-19 cells reached maximum levels at 3 h, and MCP-1 and IL-8 protein in the culture media reached maximum levels at 24 h. Berberine dose-dependently inhibited MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA expression of the cells and protein levels in the media stimulated with LPS.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that berberine inhibited the expression of MCP-1 and IL-8 induced by LPS.

Keywords: Berberine, Human retinal pigment epithelial cells, Lipopolysaccharide, Monocyte chemotactic protein-1, Interleukin-8

Introduction

The retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells play important roles in physiology of the retina. The main functions of RPE are phagocytosis of photoreceptor segments, absorption of light, and formation of blood–retina barrier, which regulates the ionic and metabolic gradients required for normal retinal function [1]. The RPE cells also have an important role in different pathologic processes of the retina such as age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy [2–5]. Human RPE cells isolated from donor eyes express monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) by stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [6, 7]. MCP-1 is a potent chemoattractant inducing the infiltration of monocytes and macrophages into tissues [8]. IL-8 is known as a neutrophil chemotactic factor [9]. MCP-1 and IL-8 are member of two chemotactic families [10] and are called CCL2 and CXCL8, respectively, according to a new classification system recommended by Zlotnik and Yoshie [11]. Crane et al. [12] reported that MCP-1 and IL-8 are produced at much higher levels than other chemokines tested in RPE cells. Dunn et al. [13] reported that ARPE-19, a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line, has structural and functional properties characteristic of RPE cells in vivo. Our study showed that MCP-1 and IL-8 in the culture media of ARPE-19 cells are increased by IL-1β or TNF-α [14, 15]. LPS induced MCP-1 and IL-8 in ARPE-19 cells [7, 16, 17]. The levels of chemotactic cytokines including MCP-1 and IL-8 are higher in the vitreous of patients with age-related macular degeneration [18–20], proliferative vitreoretinal diseases [21, 22], and proliferative diabetic retinopathy than in normal subjects [23–25]. These cytokines may help in stimulating the infiltration of monocytes and macrophages into eyes with such disorders [26]. Thus, MCP-1 and IL-8 may be involved in part in the pathogenesis of intraocular disorders.

Berberine (Fig. 1) is a major alkaloid isolated from medicinal herbs such as Berberis sp., Coptidis sp. rhizome, and Phellodendri sp. cortex; these plants are included in several Kampo formulae (traditional Chinese–Korean–Japanese medicine), such as Oren-gedoku-to (Huang-Lian-Jie-Du-Tang), and have been used to treat various inflammatory diseases. This alkaloid has multiple pharmacological actions, including diarrhea-treating action [27–29], anti-inflammatory effects [15, 30–36], glucose-lowering potential [37–40], cholesterol-lowering effect [41–43], and neuroprotective action [44–47]. We previously reported that berberine inhibited MCP-1 and IL-8 induced by LPS in rat uveitis in vivo [36]. In the present study, we investigated the effects of berberine on MCP-1 and IL-8 expression in ARPE-19 cells stimulated with LPS.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of berberine

Materials and methods

Cell culture

ARPE-19, a human RPE cell line, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (No. CRL-2302, Rockville, MD, USA). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium and Ham’s F12 (DMEM/F12; 1:1; Gibco-BRL, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS); penicillin, 100 U/ml; and streptomycin, 100 μg/ml, to obtain confluent cells. All cells were cultured at 37 °C under 10% CO2 and 90% moist air. Media were changed twice a week. The viability of ARPE-19 cells after incubation was assessed using trypan blue dye.

Total RNA extraction and MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA expression by real-time polymerase chain reaction

Berberine was purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, Mo., USA). The molecular weight of the alkaloid was 371.8, and the chemical structure is shown in Fig. 1. Berberine was dissolved in 50 mM dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) just before use. The final concentration of DMSO was kept at ≤0.05% in the culture media to avoid its inhibitory effects on the proliferation of the ARPE-19 cell line.

ARPE-19 cells were planted and cultured in 6-well culture plates (averaging 2.0 × 106 cells/well) for 14 days in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS. After the cells were washed twice with serum-free medium, ARPE-19 cells were preincubated for 2 h in serum-free medium with 0.05% DMSO or 0.2, 1, 5, and 25 μM of berberine for 30 min. Then, LPS (Escherichia coli, serotype 055:B5, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Mo., USA) was added to the medium and incubated. Total RNA was extracted from the cells using RNeasy Protect Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and treated with RNase-free DNase Set (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to remove any residual genomic DNA. One microgram of each total RNA was reverse transcribed using random hexamers, MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ, USA), and thermal cycler (Gene Amp PCR System 2400; Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, CT, USA). Condition of the reverse transcription included incubation at 25 °C for 10 min, reverse transcription at 48 °C for 30 min, and reverse transcriptase inactivation at 95 °C for 5 min.

cDNA was used to detect real-time PCR products for MCP-1 and IL-8 using TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ, USA) and ABI PRISM™ 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA) with TaqMan® Pre-Developed Assay Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA) for human MCP-1 and IL-8. The thermal profile for each primer consisted of 2 min at 50 °C and 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C. To compare expression patterns, mRNA template concentrations for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and the target genes were calculated using the standard curve method. The expression levels of MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA were normalized by GAPDH mRNA level in each sample, and the changes were expressed as an n-fold relative to the value of cells untreated with LPS.

MCP-1 and IL-8 protein concentrations by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ARPE-19 cells were seeded in 24-well culture plates (averaging 2.0 × 105 cells/well) and incubated for 14 days in DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% FBS. The cells were washed twice with serum-free medium and incubated in serum-free medium for 2 h. ARPE-19 cells were preincubated in serum-free medium with 0.05% DMSO or 0.2, 1, 5, and 25 μM of berberine for 30 min. Then, LPS was added to the medium, and it was incubated for 24 h. Thereafter, the supernatant was collected and stored at −70 °C until assay. MCP-1 and IL-8 protein concentrations were determined using ELISA (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and were calculated based on standard curves using concentrations of recombinant MCP-1 and IL-8 in the ranges of 51–2000 and 25–1000 pg/ml, respectively. All assays were performed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean values ± standard errors. Statistical analysis was performed using the Scheffe’s procedure for multiple comparisons of mean value. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of MCP-1 mRNA and IL-8 mRNA after stimulation with LPS in ARPE-19 cells

Cell viability was above 98%; most ARPE-19 cells incubated with LPS (5 μg/ml), 0.05% DMSO, and berberine (25 μM) for 24 h were viable.

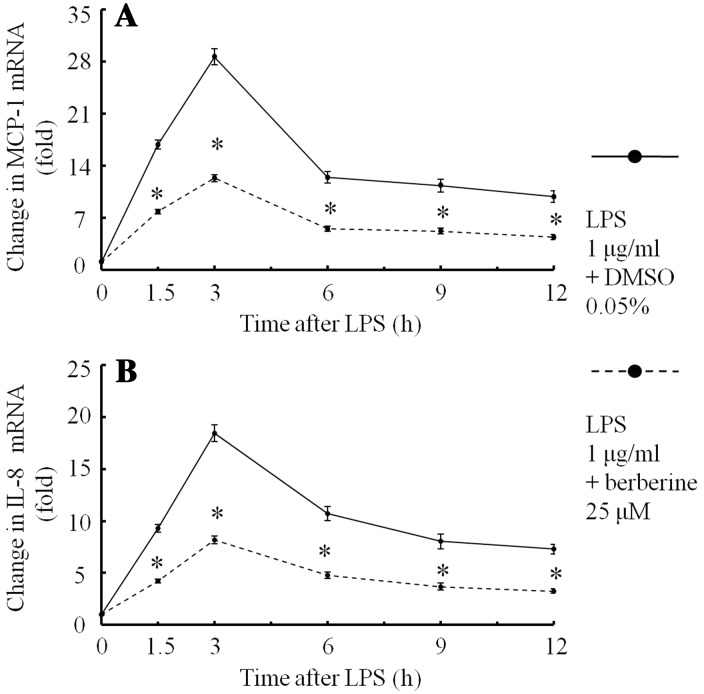

When the medium was incubated with 0.05% DMSO, ARPE-19 cells expressed small amounts of MCP-1 mRNA and IL-8 mRNA. After stimulation with LPS (1 μg/ml) and 0.05% DMSO, MCP-1 mRNA (Fig. 2a) and IL-8 mRNA (Fig. 2b) in ARPE-19 cells increased, reached maximum levels (28.4- and 18.3-fold, respectively) at 3 h, and then gradually decreased. Berberine (25 μM) inhibited these mRNA expressions in ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 2a, b).

Fig. 2.

Changes in MCP-1 mRNA and IL-8 mRNA expression after stimulation with LPS in ARPE-19 cells in serum-free media were preincubated for 30 min with berberine (25 μM) or 0.05% DMSO. After LPS (1 μg/ml) had been added to the medium, ARPE-19 cells were incubated for 1.5, 3, 6, 9, and 12 h. The changes in mRNA were determined using real-time PCR. Changes in MCP-1 mRNA (a) and IL-8 mRNA (b) after stimulation with LPS are shown. The data are expressed as means ± standard errors of four independent experiments. *P < 0.01, compared to the value without berberine

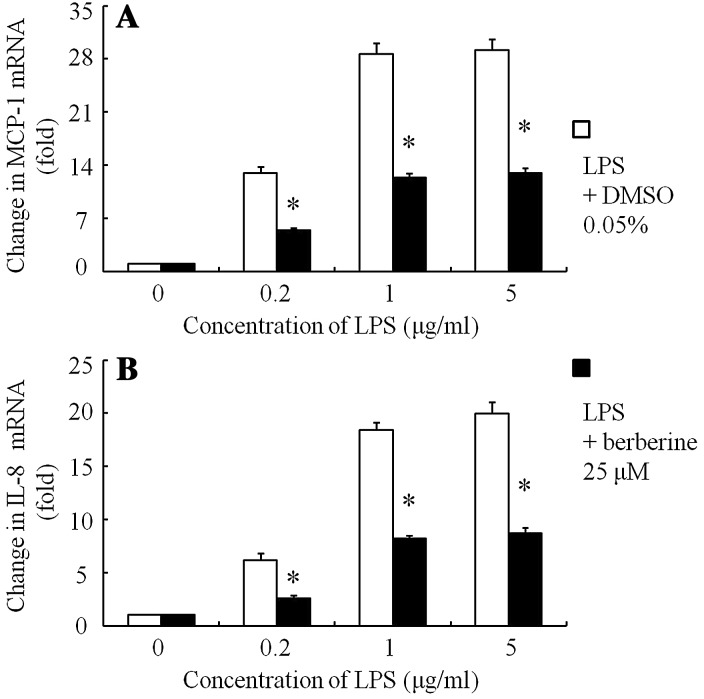

LPS (0.2–5 μg/ml) dose-dependently stimulated MCP-1 mRNA (Fig. 3a) and IL-8 mRNA (Fig. 3b) in ARPE-19 cells. Berberine (25 μM) inhibited these mRNA expressions in ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

Changes in MCP-1 mRNA and IL-8 mRNA expression after stimulation with various concentrations of LPS in ARPE-19 cells in serum-free media were preincubated for 30 min with berberine (25 μM) or 0.05% DMSO. After various concentrations of LPS (0.5, 1 and 5 μg/ml) had been added to the medium, the cells were incubated for 3 h. The changes in mRNA were determined using real-time PCR. Changes in MCP-1 mRNA (a) and IL-8 mRNA (b) after stimulation with LPS are shown. The data are expressed as means ± standard errors of four independent experiments. *P < 0.01, compared to the value without berberine

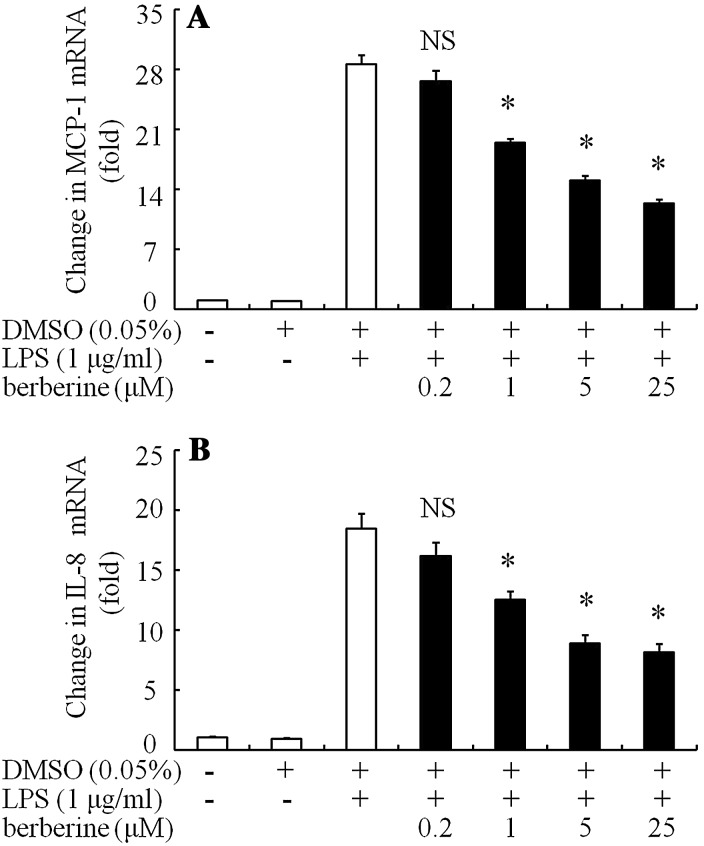

Incubation with DMSO 0.05% had only a little inhibition on MCP-1 (Fig. 4a) and IL-8 mRNA (Fig. 4b). Berberine (1–25 μM) dose-dependently inhibited MCP-1 mRNA (Fig. 4a) and IL-8 mRNA (Fig. 4b) in the cells stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) at 3 h. Berberine at 25 μM showed maximum inhibition: MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA expression, 12.2- and 8.2-fold, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Effects of berberine on MCP-1 mRNA and IL-8 mRNA expression after stimulation with LPS in ARPE-19 cells in serum-free media were preincubated for 30 min with berberine or 0.05% DMSO. LPS (1 μg/ml) was added to the media and incubated for 3 h. After incubation, total RNA was extracted from the ARPE-19 cells, and semiquantitative real-time PCR was performed. Changes in MCP-1 mRNA (a) and IL-8 mRNA (b) in ARPE-19 cells after stimulation with LPS for 3 h are shown. The data are expressed as means ± standard errors of four independent experiments. *P < 0.01; NS not significant, compared to the value of LPS-alone-treated group

MCP-1 and IL-8 protein concentrations after stimulation with LPS in ARPE-19 cells

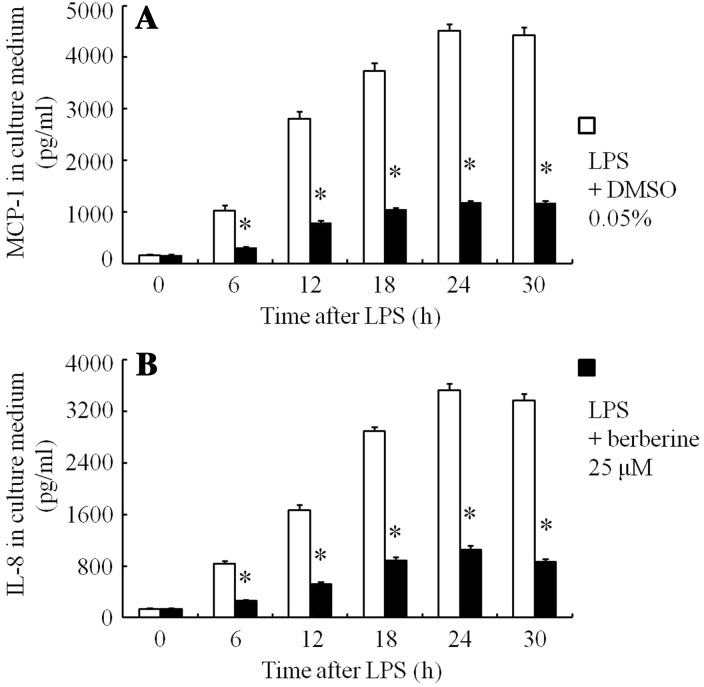

When the cells were incubated for 24 h with 0.05% DMSO, MCP-1 and IL-8 protein concentrations in the culture media were 147 and 131 pg/ml, respectively. After stimulation with LPS (1 μg/ml) and 0.05% DMSO, MCP-1 (Fig. 5a) and IL-8 (Fig. 5b) in the culture media increased and reached maximum levels (4514 and 3529 pg/ml, respectively) at 24 h, and remained so at 30 h. Berberine (25 μM) inhibited these protein levels (Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5.

Changes in MCP-1 and IL-8 protein concentrations in culture medium of ARPE-19 cells in serum-free media were preincubated for 30 min with berberine or 0.05% DMSO. After LPS (1 μg/ml) had been added to the medium, the cells were incubated for 6, 12, 18, 24, and 30 h. The MCP-1 levels (a) and IL-8 concentrations (b) in the culture media after stimulation with LPS, determined using ELISA, are shown. The data are expressed as means ± standard errors of four independent experiments. *P < 0.01, compared to the value without berberine

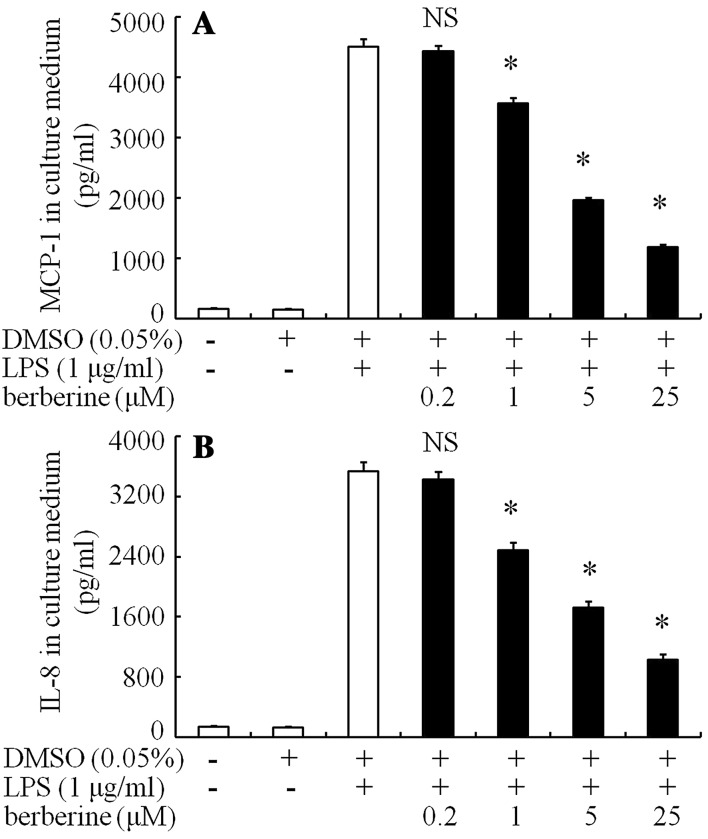

DMSO 0.05% had only a little inhibition on IL-8 and MCP-1 protein levels in the media (Fig. 6). Berberine (1–25 μM) dose-dependently inhibited LPS-stimulated MCP-1 (Fig. 6a) and IL-8 (Fig. 6b) concentrations in the culture medium at 24 h. Berberine at 25 μM showed maximum inhibition: MCP-1 and IL-8 protein levels, 1182 pg/ml (inhibition of 73.8%) and 1034 pg/ml (inhibition of 70.7%), respectively.

Fig. 6.

Effects of berberine on MCP-1 and IL-8 protein concentrations after stimulation with LPS in ARPE-19 cells were incubated for 30 min in serum-free media with berberine or 0.05% DMSO. LPS (1 μg/ml) was added to the medium and the cells were incubated for 24 h. The MCP-1 levels (a) and IL-8 protein concentrations (b) after stimulation with LPS in the culture media, determined using ELISA, are shown. The data are expressed as means ± standard errors of four independent experiments. *P < 0.01; NS not significant, compared to the value of LPS-alone-treated group

Discussion

Dunn et al. [13] have demonstrated changes in gene expression and function with time of confluence in ARPE-19 cells with a mature epithelial phenotype require as much as 2–4 weeks of culture. In the present study, therefore, ARPE-19 cells cultured for 14 days after planting were used.

In the our present findings, 0.2, 1, and 5 μg/ml LPS dose-dependently stimulated MCP-1 mRNA and IL-8 mRNA, and 5 μg/ml LPS showed had no significant difference compared with 1 μg/ml LPS in ARPE-19 cells. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of berberine were determined after stimulation of 1 μg/ml LPS in the present study. In the present study, after stimulation with LPS (1 μg/ml), MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA in ARPE-19 cells reached peak levels at 3 h, and MCP-1 and IL-8 protein in the culture media reached peak levels at 24 h. Therefore, the inhibitory effects of berberine on the MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA were determined after stimulation of LPS at 3 h, and on the MCP-1 and IL-8 protein were determined after stimulation of LPS at 24 h.

In the present study, LPS dose-dependently stimulated MCP-1 and IL-8 expression in ARPE-19 cells. High levels of the MCP-1 and IL-8 in the aqueous humor and vitreous were involved in part in the pathogenesis of intraocular disorders such as age-related macular degeneration, proliferative vitreoretinal diseases, and diabetic retinopathy [18–25]. Therefore, the treatment of these eye diseases requires the suppression of MCP-1 and IL-8 expression.

In China, berberine (5–20 mg/kg per day) has long been used in the treatment of diarrhea and gastrointestinal disorders [27, 28]. In Japan, berberine alone is not used clinically. Mixed extracts from multiple herbs, which contain several alkaloids, are administered orally. For example, Oren-gedoku-to (Huang-Lian-Jie-Du-Tang in Chinese), which contains extracts from Scutellariae sp. radix, Coptidis sp. rhizoma, Gardeniae sp. fructus, and Phellodendri sp. cortex, is prescribed for treatment of gastritis. Oren-gedoku-to (1.5 g) usually contains berberine (240 mg). Kong et al. [42] reported that oral administration of berberine (0.5 g twice per day) for 3 months lowers serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic people. The alkaloid also reported has the other pharmacological actions, including glucose-lowering potential [44–47].

We previously reported that berberine inhibited the in vivo expression of MCP-1 and IL-8 induced by LPS, decreasing the inflammatory cell infiltration and the levels of protein and cells in the aqueous humor in rat [36]. In the present study, we found that the alkaloid significantly inhibited the in vitro expression of MCP-1 and IL-8 induced by LPS in a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line. Therefore, an effect of berberine in the chemokine-mediated disorders may be expected.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Zhejiang Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Planning Project (No. 2016ZA132), and by Zhejiang Province Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (No. 2014KYA104).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bok D. The retinal pigment epithelium: a versatile partner in vision. J Cell Sci Suppl. 1993;17:189–195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.1993.Supplement_17.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanus J, Anderson C, Wang S. RPE necroptosis in response to oxidative stress and in AMD. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24(Pt B):286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanus J, Anderson C, Sarraf D, Ma J, Wang S. Retinal pigment epithelial cell necroptosis in response to sodium iodate. Cell Death Discov. 2016;2:16054. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NagasakaY Kaneko H, Ye F, Kachi S, Asami T, Kato S, Takayama K, Hwang SJ, Kataoka K, Shimizu H, Iwase T, Funahashi Y, Higuchi A, Senga T, Terasaki H. Role of caveolin-1 for blocking the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58:221–229. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simó R, Villarroel M, Corraliza L, Hernández C, Garcia-Ramírez M. The retinal pigment epithelium: something more than a constituent of the blood-retinal barrier–implications for the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:190724. doi: 10.1155/2010/190724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mai K, Chui JJ, Di Girolamo N, McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D. Role of toll-like receptors in human iris pigment epithelial cells and their response to pathogen-associated molecular patterns. J Inflamm (Lond) 2014;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung KW, Barnstable CJ, Tombran-Tink J. Bacterial endotoxin activates retinal pigment epithelial cells and induces their degeneration through IL-6 and IL-8 autocrine signaling. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1374–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rollins BJ, Walz A, Baggiolini M. Recombinant human MCP-1/JE induces chemotaxis, calcium flux, and the respiratory burst in human monocytes. Blood. 1991;78:1112–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen CG, Anderson AO, Appella E, Oppenheim JJ, Matsushima K. The neutrophil-activating protein (NAP-1) is also chemotactic for T lymphocytes. Science. 1989;243:1464–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.2648569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines-CXC and CC Chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60509-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zlotnit A, Yoshie O. Chemokines: a new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity. 2000;12:121–127. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80165-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crane IJ, Wallace CA, Mckillop-Smith S, Forrester JV. Control of chemokine production at the blood-retina barrier. Immunology. 2000;101:426–433. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2000.01105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn KC, Aotaki-Keen AE, Putkey FR, Hjelmeland LM. ARPE-19, a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line with differentiated properties. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62:155–169. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui HS, Hayasaka S, Zhang XY, Chi ZL, Hayasaka Y. Effects of α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone on interleukin-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression in a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line. Ophthalmic Res. 2005;37:279–288. doi: 10.1159/000087699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui HS, Hayasaka S, Zhang XY, Hayasaka Y, Chi ZL, Zheng LS. Effect of berberine on interleukin-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression in a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line. Ophthalmic Res. 2006;38:149–157. doi: 10.1159/000090672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollreisz A, Rafferty B, Kozarov E, Lalla E. Klebsiella pneumoniae induces an inflammatory response in human retinal-pigmented epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paeng SH, Park WS, Jung WK, Lee DS, Kim GY, Choi YH, Seo SK, Jang WH, Choi JS, Lee YM, Park S, Choi IW. YCG063 inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa LPS-induced inflammation in human retinal pigment epithelial cells through the TLR2-mediated AKT/NF-κB pathway and ROS-independent pathways. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36:808–816. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du Z, Wu X, Song M, Li P, Wang L. Oxidative damage induces MCP-1 secretion and macrophage aggregation in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254:2469–2476. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hautamäki A, Seitsonen S, Holopainen JM, Moilanen JA, Kivioja J, Onkamo P, Järvelä I, Immonen I. The genetic variant rs4073 A → T of the Interleukin-8 promoter region is associated with the earlier onset of exudative age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93:726–733. doi: 10.1111/aos.12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonas JB, Tao Y, Neumaier M, Findeisen P. Cytokine concentration in aqueous humour of eyes with exudative age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90:e381–e388. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitamura Y, Takeuchi S, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Tsukahara I, Matsuda A, Tagawa Y, Mizue Y, Nishihira J. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 levels in the vitreous of patients with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002;46:218–221. doi: 10.1016/S0021-5155(01)00497-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aksunger A, Or M, Okur H, Hasanreisoglu B, Akbatur H. Role of interleukin 8 in the pathogenesis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211:223–225. doi: 10.1159/000310794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harada C, Okumura A, Namekata K, Nakamura K, MitamuraY Ohguro H, Harada T. Role of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and nuclear factor kappa B in the pathogenesis of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;74:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrovic MG, Korosec P, Kosnik M, Hawlina M. Vitreous levels of interleukin-8 in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:175–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayasaka S, Zhang XY, Cui HS, Yanagisawa S, Chi ZL, Shimada Y. Vitreous chemokines and Sho (Zheng in Chinese) of Chinese–Korean–Japanese medicine in patients with diabetic vitreoretinopathy. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:537–543. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerszten RE, Garcia-Zepeda EA, Lim YC, Yoshida M, Ding HA, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Luster AD, Luscinskas FW, Rosenzweig A. MCP-1 and IL-8 trigger firm adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelium under flow conditions. Nature. 1999;398:718–723. doi: 10.1038/19546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen C, Yu Z, Li Y, Fichna J, Storr M. Effects of berberine in the gastrointestinal tract–a review of actions and therapeutic implications. Am J Chin Med. 2014;42:1053–1070. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X14500669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen C, Tao C, Liu Z, Lu M, Pan Q, Zheng L, Li Q, Song Z, Fichna J. A randomized clinical trial of berberine hydrochloride in patients with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Phytother Res. 2015;29:1822–1827. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subbaiah TV, Amin AH. Effect of berberine sulphate on entamoeba histolytica. Nature. 1967;215:527–528. doi: 10.1038/215527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuo CL, Chi CW, Liu TY. The anti-inflammatory potential of berberine in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2004;203:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi SB, Bae GS, Jo IJ, Wang S, Song HJ, Park SJ. Berberine inhibits inflammatory mediators and attenuates acute pancreatitis through deactivation of JNK signaling pathways. Mol Immunol. 2016;74:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin K, Liu S, Shen Y, Li Q. Berberine attenuates cigarette smoke-induced acute lung inflammation. Inflammation. 2013;36:1079–1086. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng WE, Ying Chang M, Wei JY, Chen YJ, Maa MC, Leu TH. Berberine reduces Toll-like receptor-mediated macrophage migration by suppression of Src enhancement. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;757:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayasaka S, Kodama T, Ohira A. Traditional Japanese herbal (kampo) medicines and treatment of ocular diseases: a review. Am J Chin Med. 2012;40:887–904. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Wang Q, Xie M, Liu P, Qi X, Liu X, Li Z. Berberine exerts an anti-inflammatory role in ocular Behcet’s disease. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:97–102. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui HS, Hayasaka S, Zheng LS, Hayasaka Y, Zhang XY, Chi ZL. Effect of berberine on monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1 expression in rat lipopolysaccharide-induced uveitis. Ophthalmic Res. 2007;39:32–39. doi: 10.1159/000097904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu C, Wang Z, SongY WuD, Zheng X, Li P, Jin J, Xu N, Li L. Effects of berberine on amelioration of hyperglycemia and oxidative stress in high glucose and high fat diet-induced diabetic hamsters in vivo. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:313808. doi: 10.1155/2015/313808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Li X, Zou D, Liu W, Yang J, Zhu N, Huo L, Wang M, Hong J, Wu P, Ren G, Ning G. Treatment of type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia with the natural plant alkaloid berberine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2559–2565. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Wei J, Xue R, Wu JD, Zhao W, Wang ZZ, Wang SK, Zhou ZX, Song DQ, Wang YM, Pan HN, Kong WJ, Jiang JD. Berberine lowers blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients through increasing insulin receptor expression. Metabolism. 2010;59:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pirillo A, Catapano AL. Berberine, a plant alkaloid with lipid- and glucose-lowering properties: from in vitro evidence to clinical studies. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li XY, Zhao ZX, Huang M, Feng R, He CY, Ma C, Luo SH, Fu J, Wen BY, Ren L, Shou JW, Guo F, Chen Y, Gao X, Wang Y, Jiang JD. Effect of berberine on promoting the excretion of cholesterol in high-fat diet-induced hyperlipidemic hamsters. J Transl Med. 2015;13:278. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0629-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kong W, Wei J, Abidi P, Lin M, Inaba S, Li C, Wang Y, Wang Z, Si S, Pan H, Wang S, Wu J, Wang Y, Li Z, Liu J, Jiang JD. Berberine is a novel cholesterol-lowering drug working through a unique mechanism distinct from statins. Nature Med. 2004;10:1344–1351. doi: 10.1038/nm1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YH, Yang P, Kong WJ, Wang YX, Hu CQ, Zuo ZY, Wang YM, Gao H, Gao LM, Feng YC, Du NN, Liu Y, Song DQ, Jiang JD. Berberine analogues as a novel class of the low-density-lipoprotein receptor up-regulators: synthesis, structure-activity relationships, and cholesterol-lowering efficacy. J Med Chem. 2009;52:492–501. doi: 10.1021/jm801157z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui HS, Matsumoto K, Murakami Y, Hori H, Zhao Q, Obi R. Berberine exerts neuroprotective actions against in vitro ischemia-induced neuronal cell damage in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures: involvement of B-cell lymphoma 2 phosphorylation suppression. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:79–85. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Oliveira Juliana Sorraila, Abdalla Fátima Husein, Dornelles Guilherme Lopes, Adefegha Stephen Adeniyi, Palma Taís Vidal, Signor Cristiane, da Silva Bernardi Jamile, Baldissarelli Jucimara, Lenz Luana Suéling, Magni Luana Pereira, Rubin Maribel Antonello, Pillat Micheli Mainardi, de Andrade Cinthia Melazzo. Berberine protects against memory impairment and anxiogenic-like behavior in rats submitted to sporadic Alzheimer’s-like dementia: Involvement of acetylcholinesterase and cell death. NeuroToxicology. 2016;57:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou J, Du X, Long M, Zhang Z, Zhou S, Zhou J, Qian G. Neuroprotective effect of berberine is mediated by MAPK signaling pathway in experimental diabetic neuropathy in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;774:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar A, Ekavali Mishra J, Chopra K, Dhull DK. Possible role of P-glycoprotein in the neuroprotective mechanism of berberine in intracerebroventricular streptozotocin-induced cognitive dysfunction. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:137–152. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]