Abstract

Background:

Syzygium cumini, Terminalia chebula, Trigonella foenum graecum and Salvadora persica are medicinally important plants well known for their pharmacological activities.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to compare the antidiabetic potential of partially purified bioactive fractions isolated from four targeted medicinal plants in diabetic rats.

Methods:

Alloxan was administered (125 mg/kg, IP) in albino Wistar rats to produce diabetes. The partially purified bioactive fractions, namely S. cumini tannin fraction (ScTF), T. foenum graecum (Fenugreek) saponin fraction (FgSF), T. chebula flavonoid fraction (TcFF) and S. persica flavonoid fraction (SpFF), were administered to diabetic rats with the dose of 100 mg/kg, per oral (PO) and the effect of the fractions on body weight, liver glycogen and serum glucose were studied up to 15 days.

Results:

The results have indicated that diabetic rats treated with fractions showed a statistically significant (P < 0.05) decrease in serum glucose and increase in body weight and liver glycogen. Among ScTF, FgSF, TcFF and SpFF possesse better hypoglycemic activity in all models.

Conclusion:

The present investigation reveals that flavonoid isolated from S. persica is useful in the management of diabetes mellitus because of ability to regulate glucose level and reduce related complications.

Keywords: Alloxan, Antidiabetic activity, Salvadora persica, Syzygium cumini, Terminalia chebula

Introduction

Natural products have been used since ancient times in the traditional system of medicine for the treatment of diabetes.[1] These secondary metabolites include a large and diverse group of substances that serve as a source of most of the active ingredients of medicines.[2] Plant-derived secondary metabolites have long been the basis of drug discovery and drug development, as combinatorial chemistry presents an opportunity for the rational design of lead compounds to target specific molecules.[3,4] Numerous studies have validated the traditional use of antidiabetic medicinal plants by investigating the biologically active compound in the extracts which is being able to reduce postprandial blood sugar level. Numerous phytochemicals including alkaloids, phenol, polyphenols, terpenoids, flavonoids and tannins present in the active plant extract, are thought to be accountable not only for their antidiabetic activity but also for various pharmacological activities.[5] For example, tannins extracted from S. cumini Skeels bark have been reported to exert gastroprotective and anti-ulcerogenic effects on HCl/ethanol induced gastric mucosal injury in Sprague-Dawley rats.[6] Uemura et al. demonstrated that diosgenin, a phytosteroid sapogenin, isolated from fenugreek improved hepatic steatosis and hyperlipidemia by suppressing the mRNA expression of lipogenic genes in the liver of obese diabetic mice.[7] Srivastav et al. found that a flavonoid-rich extract of T. chebula ameliorates contraceptive efficacy in male albino rats.[8] Flavonoids identified in S. persica are useful in the prevention of arteriosclerosis, cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative diseases as well as possess anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic, anticancer, antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-allergic, antihypertensive and anti-arthritic properties.[9]

Diabetes is associated with the impaired carbohydrates, fats and protein metabolism characterized by chronic hyperglycemia, resulting from defects in insulin secretion, insulin action or both.[10] If the disease is not treated properly, it generates both microvascular and macrovascular complications leading to mortality, hence glycemic control is required to prevent these long term complications. Phytotherapy that is, treatment with the bioactive phytoconstituents obtained from medicinal plants is the potential mechanistic perspective in the management of diabetes.[11] Although lot of antidiabetic agents are available to treat the disease, the total recovery, which avoids adverse effects, late-stage diabetic complications, and prove satisfactory in maintaining euglycemia, has not yet been reported till date. Hence, the search is still continued for an orally effective drug from natural plant products.[12]

Methods

Collection of plant material

Plant samples, including seeds of T. foenum graecum and T. chebula were purchased from the local market, while S. cumini seeds and S. persica leaves were collected from a local region of Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India and were authenticated by the Department of Botany, Padmashri Vikhe Patil College, Pravaranagar (Loni), Tal: Rahata, District Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India.

Preparation of extracts

Each plant material, that is, T. foenum graecum seeds, S. cumini seeds, S. persica leaves and T. chebula seeds was ground into a fine powder and was subjected to successive extraction by maceration in solvents with increasing order of their polarity such as petroleum ether, chloroform, ethanol and aqueous solvent. All extracts were then filtered through Whatman filter paper. Filtrates of organic solvents (petroleum ether, chloroform and ethanol) were concentrated using a rotary evaporator while aqueous extracts were frozen at −77°C and finally lyophilized at −46°C.[13] All these fractions were then subjected for in vitro antidiabetic evaluation as mentioned in our previous research papers[14,15,16,17] and the most potential one among the four solvent fractions of each plant, that is, chloroform extract of T. foenum graecum, ethanol extract of S. cumini, aqueous extract of S. persica and petroleum ether extract of T. chebula were selected for further thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and in vivo analysis.

Thin-layer chromatography and identification of nature of bioactive fractions

TLC and nature of partially purified bioactive fractions were performed as previously described.[18]

Animals

Male albino Wistar rats weighing 150–250 g, 11 weeks old were used for the study. The animals were housed in spacious, labeled cages at 26°C ± 2°C, and maintained under standard 12 h light/12 h dark cycle throughout the study. They were given access to rodent pellet and water ad libitum. The experimental protocols and procedures used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC reg.no. ARCMR/PIMS/IAEC38/2012) under strict compliance of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals guidelines.

Toxicity test

The toxicity test of partially purified bioactive compounds was studied as per Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development guidelines. High concentration bioactive compounds (5000 mg/rat) prepared in saline were administered per orally to groups of three rats each for 7 consecutive days. The rats were then observed for any abnormal behavior such as respiratory distress, hyperexcitability, diarrhea, salivation, motor impairment and any lethality or death.[19]

Induction of diabetes in experimental rats

Diabetes was induced experimentally by a single intraperitoneal administration of 125 mg/kg body weight of a freshly prepared alloxan monohydrate (10% in normal saline). The rats were kept for next 24 h on 5% w/v glucose solution bottles in their cages to prevent sudden hypoglycemia. After 72 h, animals from all groups were subjected to serum glucose estimation. The blood samples were collected by puncturing the retro-orbital sinus. Animals in group which showed the serum glucose level >200 mg/dl were selected for the study.[20]

Experimental design

Seven groups of rats, n = 6 in each group received following treatment schedule.

Group I: Normal control (0.1 ml normal saline)

Group II: Negative control (diabetic without treatment)

Group III: Positive control (diabetic + glibenclamide 5 mg/kg, (PO)

Group IV: Diabetic + S. cumini tannin fraction (ScTF) (100 mg/kg, (PO 0.1 ml normal saline,)

Group V: Diabetic + T. foenum graecum (Fenugreek) saponin fraction (FgSF) (100 mg/kg, PO 0.1 ml normal saline)

Group VI: Diabetic + T. chebula flavonoid fraction (TcFF) (100 mg/kg, PO 0.1 ml normal saline)

Group VII: Diabetic + S. persica FF (SpFF) (100 mg/kg, PO in 0.1 ml normal saline).

Bioactive fraction, standard drug glibenclamide (5 mg/kg) and saline were administered using feeding cannula. Group I served as normal control, which received saline for 15 days. Group II to Group VII were alloxan-induced diabetic rats and were given a fixed dose of bioactive fraction (100 mg/kg, PO in 0.1 ml normal saline) and standard drug glibenclamide (5 mg/kg) for 15 consecutive days. The blood samples were collected by puncturing the retro-orbital sinus on day 1st, 4th, 7th and 15th of the treatment.

Oral glucose tolerance test

The entire groups of normal rats were fasted overnight (18 h) before OGTT. After 1 h of feeding of partially purified fractions, rats were given glucose 3 g/kg per orally 30 min after the fraction and/or drug administration. At 30, 90 and 150 min interval after glucose loading, blood samples (serum) were collected by puncturing the retro-orbital sinus. Serum glucose level was measured by the glucose oxidase method immediately after separation of serum from the blood.[21]

Biochemical parameters

Serum glucose was estimated using Biochemical autoanalyzer (Robonik, India, Pvt. Ltd.) and glucose estimation kit, 10 μl serum was used for each assay. Liver glycogen was estimated according to the Carroll et al.[22]

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was done using (ANOVA) and Dunnett test to compare the data. (P < 0.05 ± was considered a statistically significant. Values are presented as means ± standard deviation.

Results

The acute toxicity studies revealed the nontoxic nature of the ScTF, FgSF, TcFF, and SpFF. There was no lethality or any toxic reactions found at any of four plants doses selected until the end of the study period.

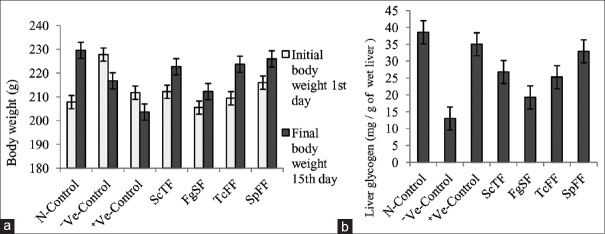

Figure 1a showed the effect of four partially purified bioactive compounds isolated from selected plants, namely ScTF, FgSF, TcFF and SpFF, on the body weight changes of diabetic rats as compared to normal rats and rats received standard drug glibenclamide. During the 2 weeks of observation of the treated diabetic rats, there was weight gain, relative to 1st day of start of the treatment. The untreated diabetic rats lost their body weight significantly as compared to normal control. The diabetic rats treated with glibenclamide also showed decrease in body weight compared to that of normal control.

Figure 1.

(a) Changes on body weight after oral administration of partially purified bioactive fractions from different plants in diabetic rats. (b) Changes on liver glycogen levels after administration of partially purified bioactive fractions from different plants in diabetic rats

Figure 1b showed the effect of four partially purified compounds isolated from targeted plants, namely ScTF, FgSF, TcFF and SpFF, on liver glycogen of diabetic rats as compared to normal rats and standard drug glibenclamide. Negative control, that is diabetic untreated rats showed significantly decreased levels of glycogen, i.e. 12.99 ± 1.66 mg versus 38.60 ± 4.83 mg/g of wet liver of normal rats. However, treatment with partially purified compounds significantly elevated glycogen levels in diabetic rats. SpFF increased levels equally with that of glibenclamide able to increase liver glycogen.

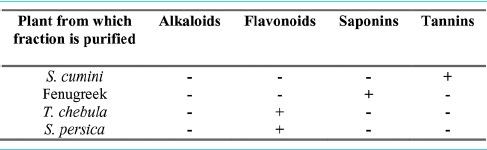

Table 1 showed the phytochemical screening of four partially purified bioactive fractions from different plants revealing the presence of tannins, saponins and flavonoids.

Table 1.

Three different phytochemicals were found in the four partially purified bioactive fractions from different plants

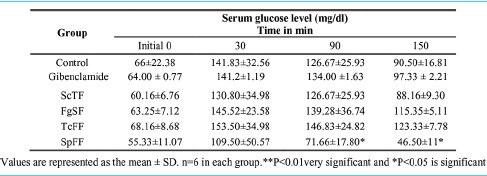

Table 2 showed the hypoglycemic effect of different doses of ScTF, FgSF, TcFF and SpFF on fasting OGTT of normal rats and diabetic rats assessed at different time intervals. The serum glucose level at different time intervals, i.e. 30, 90 and 150 min were compared with initial 0 min serum glucose level of their respective groups. There was statistically significant (P < 0.05) decrease in serum glucose level at different time interval in SpFF-treated group at 90 and 150 min when compared to initial, serum glucose level. The ScTF-treated groups also reduced serum glucose level at 150 min when compared with the respective serum glucose level of the control group.

Table 2.

Hypoglycemic effect of partially purified bioactive fractions from different plants on serum glucose level in oral glucose tolerance test in fasted rats

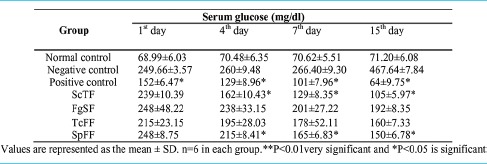

Table 3 showed the effect of ScTF, FgSF, TcFF and SpFF on serum glucose level in normal and alloxan induced diabetic rats. Serum glucose levels were checked on 1st, 4th, 7th and 15th day. It was observed that the serum glucose level in diabetic rats was significantly increased when compared with normal rats. Oral administration of partially purified bioactive fractions showed a highly significant reduction in the serum glucose level starting at the 4th day of treatment, compared to 1st day as well as compared to negative (untreated) control values of diabetic rats in the corresponding days. On the other hand, glibenclamide treatment of diabetic rats showed a significant reduction in serum glucose levels at the 2nd day, which gradually decreased till 15th day in comparison with untreated diabetic rats. In the negative control (diabetic) group, out of the 6 animals, 2 animals were died of diabetes, one on the 7th day and another one died on the 15th day.

Table 3.

Hypoglycemic effect of partially purified bioactive fractions from different plants on serum glucose level in alloxan-induced diabetic rats

Discussion

Alloxan-induced diabetic rats are one of the animal models used for diabetic studies.[23] Alloxan (2, 4, 5, 6-tetraoxypyrimidine; 5, 6-dioxyuracil) induces diabetes by evoking a sudden rise in insulin secretion which is responsible to suppress the islet response to glucose.[24,25] Overproduction of hepatic glucose further leads to the death of pancreatic cells. Alloxan-induced diabetic rats showed symptoms such as polydypsia, polyuria, body weight loss, ketonuria and hyperglycemia.[26] Glibenclamide is frequently used standard in diabetic rats to compare the efficacy of various drugs or herbal preparations.[27]

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that compared the antidiabetic effect of partially purified bioactive fractions isolated from four different plants in experimental diabetes. First, extracts have been fractionated using solvents with increasing order of their polarity. All 16 fractions from four target plants were screened in vitro and the four fractions showing highest activity each from four plant solvent fractions were selected for further TLC analysis. Partially purified bioactive fractions were then scratched off and analyzed for its in vivo characterization.

In our study, diabetic untreated rat showed weight loss which may be due to one of the following reasons: excessive breakdown of tissue proteins,[28] dehydration, catabolism of fats and proteins,[29] muscle wasting,[30] etc. Oral administration of partially purified bioactive fractions to the diabetic rats for consecutive 15 days showed improvement in their body weight, indicating that the partially purified fractions had beneficial effect in preventing loss of body weight of diabetic rats. The probable mechanism of this benefit is due to a better control of hyperglycemic state and decreased fasting blood glucose level could improve body weight in diabetic rats.[31] SpFF-treated diabetic rats were shown good results in comparison with control.

The liver plays a crucial role in glucose metabolism, especially in postprandial glycogen storage as well as glycogen depletion in overnight fasting. In people with diabetes, liver looses its normal capacity to synthesize glycogen as glycogen synthase activation becomes defective.[32] Therefore, our result showed decreased liver glycogen in negative control, that is, an untreated diabetic group. Diabetic rats treated with partially purified bioactive fractions are proved to be effective in the recovery of liver glycogen. Increased secretion of insulin may be responsible for glycogenesis. As compared to normal control and positive control SpFF have shown a better recovery in liver glycogen.[33]

Considering the OGTT, partially purified bioactive fractions treated diabetic rats showed significant decrease in serum glucose concentration at 90 min and 150 min interval. Among the four partially purified bioactive fractions, SpFF brought an effective hypoglycemic effect when compared to other bioactive fractions. The anti-hyperglycemic effect may occur due to one of the two reasons, (i) reduction in intestinal glucose absorption and (ii) induction of glycogenic process including reduction in glycogenolysis and glyconeogenesis.[34]

While planning the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, the three factors those should be taken care of insulin deficiency, insulin resistance and increased hepatic glucose output.[35] At present, there are five different types of hypoglycemic agents such as sulfonylureas, meglitinides, biguanides, thiazolidinediones and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors are available displaying unique pharmacological properties.[36] Glibenclamide which we used as a control is a class of sulfonylureas acts as insulin secretagogues, that is, it stimulates insulin release from the insulin-secreting ß-cells situated in the pancreas and may slightly improve insulin resistance in peripheral target tissues such as muscle and fat. They have specific receptor present on pancreatic b-cells. Binding of the drug to these cells leads to inhibition of ATP-dependent potassium channel, altering calcium influx and stimulation of insulin secretion. Sulfonylureas reduce fasting plasma glucose by 60–70 mg/dL. In this study, it found that SpFF is able to reduce glucose levels by 63 mg/dL. Like sulfonylurea, it may directly stimulate the insulin secretion. Furthermore, in this study fractions are proven good in maintaining the proper body weight, which is one of the important characteristics of sulfonylurea drugs. Hence, this study claims one possibility that SpFF fraction has a similar mechanism as that of sulfonylurea. Some oral antidiabetic drugs act by increasing insulin action and glucose-mediated utilization in peripheral tissues such as liver and muscles and decreasing hepatic glucose output. Biguanides come under this class of drugs and are suggested to prescribe up to 500 mg−2,2000 mg/day of dose.[37]

Correlating with our studies, SpFF fraction shown better recovery of liver glycogen, which is an important factor in regulation of blood glucose level. Other hypoglycemic agents, though they found effective in curing diabetes up to some extent, they are associated with some side effects.[38]

An attempt was made to analyze the antidiabetic effect of partially purified bioactive fractions on serum glucose level. Parameters for antidiabetic activity were measured before and on 1st, 4th, 7th and 15th day. Glibenclamide shown better serum glucose level reduction as compared to normal. In comparison to all bioactive fractions, diabetic rats treated with ScTF and SpFF reported significant (P < 0.05) reduction of serum glucose level compared to control diabetic rats after 4th up to 15th days of treatment. Phytochemicals isolated from medicinal plants have been reported to show antidiabetic activity.[39] Phytoconstituents such as alkaloids, glycosides, polysaccharides and phenolics such as flavonoids, terpenoids and steroids are the most prevalent among phytochemical groups. From the data obtained in our current analysis, it was observed that the partially purified phytoconstituents, that is, saponins, tannins and flavonoids showed prominent antidiabetic properties in vivo. Out of all four phytoconstituents purified, flavonoids isolated from S. persica showed significant levels of bioactive compound as well as potent antidiabetic activity and anti-hyperglycemic effect, especially by improving liver glycogen and body weight of the treated diabetic rats. Tannins isolated from S. cumini also showed the best result for antidiabetic potential, but less anti-hyperglycemic effect as well as less effect on body weight and liver glycogen content in comparison with S. persica.

Conclusion

The present study concludes that tannins, saponins and flavonoids isolated from targeted medicinal plants demonstrated significant decrease of serum sugar level and apparent improvement in glucose tolerance in the single administration study. Hence, it is clear that these compounds could give hypoglycemic effect in people with diabetes, especially in case of high postprandial glucose level. All these compounds were found safe. Flavonoids isolated from S. persica were found more potent than other targeted plants. Investigations should be undertaken to elucidate specific active molecule responsible for activity and whether those actions of purified molecule are mediated by a single component or a synergistic action.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Shapiro K, Gong WC. Natural products used for diabetes. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002;42:217–26. doi: 10.1331/108658002763508515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey AL. Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ji HF, Li XJ, Zhang HY. Natural products and drug discovery. Can thousands of years of ancient medical knowledge lead us to new and powerful drug combinations in the fight against cancer and dementia? EMBO Rep. 2009;10:194–200. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balandrin MF, Kinghorn AD, Farnsworth NR. ACS Symposium Series 534. Washington, DC: ACS Publications; 1993. Plant-Derived Natural Products in Drug Discovery and Development. Human Medicinal Agents from Plants; pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaikwad SB, Mohan GK, Rani MS. Phytochemicals for diabetes management. Pharm Crops. 2014;5:11–28. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramirez RO, Roa CC., Jr The gastroprotective effect of tannins extracted from duhat (Syzygium cumini skeels) bark on HCl/ethanol induced gastric mucosal injury in Sprague-Dawley rats. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2003;29:253–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uemura T, Goto T, Kang MS, Mizoguchi N, Hirai S, Lee JY, et al. Diosgenin, the main aglycon of fenugreek, inhibits LXRα activity in hepG2 cells and decreases plasma and hepatic triglycerides in obese diabetic mice. J Nutr. 2011;141:17–23. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.125591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastav A, Chandra A, Singh M, Jamal F, Rastogi P, Rajendran SM, et al. Inhibition of hyaluronidase activity of human and rat spermatozoa in vitro and antispermatogenic activity in rats in vivo by Terminalia chebula, a flavonoid rich plant. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;29:214–24. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noumi E, Hajlaoui H, Trabelsi N, Ksouri R, Bakhrouf A, Snoussi M. Antioxidant activities and RP-HPLC identification of polyphenols in the acetone 80 extract of Salvadora persica. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;5:966–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel DK, Kumar R, Laloo D, Hemalatha S. Diabetes mellitus: An overview on its pharmacological aspects and reported medicinal plants having antidiabetic activity. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2:411–20. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60067-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Abhar HS, Schaalan MF. Phytotherapy in diabetes: Review on potential mechanistic perspectives. World J Diabetes. 2014;5:176–97. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i2.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey A, Tripathi P, Pandey R, Srivatava R, Goswami S. Alternative therapies useful in the management of diabetes: A systematic review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3:504–12. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.90103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senguttuvan J, Paulsamy S, Karthika K. Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of leaf and root parts of the medicinal herb, Hypochaeris radicata L. For in vitro antioxidant activities. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:S359–67. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bansode TS, Gupta A, Chaphalkar SR, Salalkar BK. Integrating in silico and in vitro approaches to screen the antidiabetic drug from Trigonella foenum graecum Linn. Int J Biochem Res Rev. 2016;14:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bansode TS, Gupta A, Salalkar BK. In silico and in vitro assessment on antidiabetic efficacy of secondary metabolites from Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels. Plant Sci Today. 2016;3:360–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bansode TS, Salalkar BK. Exploiting the therapeutic potential of secondary metabolites from Salvadora persica for diabetes using in silico and in vitro approach. J Life Sci Biotechnol. 2016;5:127–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bansode TS, Salalkar BK. Strategies in the design of antidiabetic drugs from Terminalia chebula using in silico and in vitro approach. Micro Med. 2016;4:60–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bansode TS, Gupta A, Shinde B, Salalkar BK. Partial purification and antidiabetic effect of bioactive compounds isolated from medicinal plants. Micro Med. 2017;5:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paris: OECD; 2002. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals/Section 4: Health Effects Test No. 423: Acute Oral Toxicity – Acute Toxic Class Method. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenzen S. The mechanisms of alloxan – And streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:216–26. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergmeyer HU, Bernt E. Glucose determination with glucose oxidase and peroxidase. In: Bergmeyer HU, editor. Methods of Enzyme Analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 1205–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll NV, Longley RW, Roe JH. The determination of glycogen in liver and muscle by use of anthrone reagent. J Biol Chem. 1956;220:583–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivasan K, Ramarao P. Animal models in type 2 diabetes research: An overview. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:451–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruckmann G, Wertheimer E. Alloxan studies; the action of alloxan homologues and related compounds. J Biol Chem. 1947;168:241–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szkudelski T. The mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in B cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol Res. 2001;50:537–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geetha G, Kalavalarasariel Gopinathapillai P, Sankar V. Anti diabetic effect of Achyranthes rubrofusca leaf extracts on alloxan induced diabetic rats. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2011;24:193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandhi GR, Sasikumar P. Antidiabetic effect of Merremia emarginata burm.f. in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2:281–6. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60023-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamalakkannan N, Prince PS. Antihyperglycaemic and antioxidant effect of rutin, a polyphenolic flavonoid, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic wistar rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hakim ZS, Patel BK, Goyal RK. Effects of chronic ramipril treatment in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;41:353–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajkumar L, Srinivasan N, Balasubramanian K, Govindarajulu P. Increased degradation of dermal collagen in diabetic rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 1991;29:1081–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pari L, Saravanan R. Antidiabetic effect of diasulin, a herbal drug, on blood glucose, plasma insulin and hepatic enzymes of glucose metabolism in hyperglycaemic rats. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2004;6:286–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-8902.2004.0349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.König M, Bulik S, Holzhütter HG. Quantifying the contribution of the liver to glucose homeostasis: A detailed kinetic model of human hepatic glucose metabolism. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ananda PK, Kumarappan CT, Sunil C, Kalaichelvan VK. Effect of Biophytum sensitivum on streptozotocin and nicotinamide-induced diabetic rats. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2:31–5. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60185-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anusooriya P, Malarvizhi D, Gopalakrishnan VK, Devaki K. Antioxidant and antidiabetic effect of aqueous fruit extract of Passiflora ligularis juss. On streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:130342. doi: 10.1155/2014/130342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fröde TS, Medeiros YS. Animal models to test drugs with potential antidiabetic activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115:173–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luna B, Feinglos MN. Oral agents in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1747–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenzati B, Zucco C, Miglietta S, Lamberti F, Bruno G. Oral hypoglycemic drugs: Pathophysiological basis of their mechanism of actionOral hypoglycemic drugs: Pathophysiological basis of their mechanism of action. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2010;3:3005–20. doi: 10.3390/ph3093005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stein SA, Lamos EM, Davis SN. A review of the efficacy and safety of oral antidiabetic drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2013;12:153–75. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.752813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Firdous SM. Phytochemicals for treatment of diabetes. EXCLI J. 2014;13:451–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]