Abstract

Background

Open abdomen (OA) may be required in patients with abdominal trauma, sepsis or compartment syndrome. Vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction (VAWCM) is a widely used approach for temporary abdominal closure to close the abdominal wall. However, this method is associated with a high incidence of re-operations in short term and late sequelae such as incisional hernia. The current study aims to compare the results of surgical strategies of OA with versus without permanent mesh augmentation.

Methods

Patients with OA treatment undergoing vacuum-assisted wound closure and an intraperitoneal onlay mesh (VAC-IPOM) implantation were compared to VAWCM with direct fascial closure which represents the current standard of care. Outcomes of patients from two tertiary referral centers that performed the different strategies for abdominal closure after OA treatment were compared in univariate and multivariate regression analysis.

Results

A total of 139 patients were included in the study. Of these, 50 (36.0%) patients underwent VAC-IPOM and 89 (64.0%) patients VAWCM. VAC-IPOM was associated with reduced re-operations (adjusted incidence risk ratio 0.48 per 10-person days; CI 95% = 0.39–0.58, p < 0.001), reduced duration of stay on intensive care unit (ICU) [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 0.53; CI 95% = 0.36–0.79, p = 0.002] and reduced hospital stay (aHR 0.61; CI 95% = 0.040–0.94; p = 0.024). In-hospital mortality [22.5 vs 18.0%, risk difference − 4.5; confidence interval (CI) 95% = − 18.2 to 9.3; p = 0.665] and the incidence of intestinal fistula (18.0 vs 22.0%, risk difference 4.0; CI 95% = −10.0 to 18.0; p = 0.656) did not differ between the two groups. In Kaplan–Meier analysis, hernia-free survival was significantly increased after VAC-IPOM (p = 0.041).

Conclusions

In patients undergoing OA treatment, intraperitoneal mesh augmentation is associated with a significantly decreased number of re-operations, duration of hospital and ICU stay and incidence of incisional hernias when compared to VAWCM.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10029-018-1798-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Open abdomen, Vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction, Mesh augmentation, Non-absorbable mesh

Introduction

Open abdomen (OA) treatment with temporary abdominal closure using negative-pressure wound therapy has become a standard of care in trauma patients undergoing damage control surgery [1]. OA is also increasingly used in non-trauma patients with abdominal sepsis or abdominal compartment syndrome as a life-saving procedure, especially in the growing older population with increased comorbidities and limited physiologic reserve [2].

Temporary abdominal closure needs to ensure the integrity of the abdominal wall and to compartmentalize abdominal contents to avoid treatment-related complications (e.g., intestinal fistula, inability to close the abdominal wall). Several methods for temporary abdominal closure have been described of which vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction (VAWCM) has been reported to be associated with the lowest fistula rate with high rates of fascial closure [3]. However, using the VAWCM technique, multiple surgical revisions are often required for definitive abdominal closure, which may lead to a prolonged ICU and total hospital duration of stay [4]. In addition, these patients exhibit a high rate of incisional hernias of up to 66% during long-term follow-up potentially because of local fascial traction [5].

Therefore, novel strategies to support the abdominal wall in these patients are required. Synthetic mesh implantation has been shown to effectively support the abdominal wall [6]. However, the use of such meshes in OA may have been limited due to the lack of robust data and due to reports of mesh related complications [7]. We have previously shown that the use of synthetic meshes in patients with peritonitis or fascial dehiscence is an effective approach [8, 9]. Thus, a therapeutic algorithm that includes mesh-augmented definitive abdominal closure (VAC-IPOM) in this severely ill patient’ population has been developed and introduced at the Bern University Hospital in 2005. The aim of this large two-centre study was to compare this VAC-IPOM technique with the current standard of care (VAWCM) in patients undergoing OA treatment.

Materials and methods

Study design

All consecutive patients treated for OA between January 2005 and December 2015 from two centers were analyzed. The participating centers were the Department for Visceral Surgery and Medicine, Bern University Hospital, Switzerland (patients with VAC-IPOM) and the Department for Surgery, Medical University of Vienna, General Hospital Vienna, Austria (patients with VAWCM). Patients not using the VAC-IPOM technique at the University Hospital of Bern (n = 22) were excluded from the study. Cantonal ethics committee of Bern, Switzerland and the institutional review board of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria have approved this study.

Outcome parameters

The primary outcome parameter was hernia-free survival. Secondary outcome parameters comprised of general complications such as re-operations, duration of hospital stay, duration of stay on intensive care unit (ICU), mortality and mesh-associated complications such as intestinal fistula and surgical site infection (SSI). SSI infection was defined according to CDC criteria [10]. Intestinal fistula was defined as the persistent leakage of bowel contents within 100 days of the initial OA.

Surgical strategy

VAWCM group

OA was covered with abdominal dressings and dynamic tension on fascia was applied to avoid fascial retraction. Dynamic tension on fascia was applied either via vessel loops or temporary inlay meshes as previously described [11, 12]. The vessel loops were sutured to the anterior sheet of the rectus muscle and constant tension was applied to approximate the fascial edges. In addition, 18 (22.2%) patients received a temporary large-pore polypropylene inlay mesh. The mesh was sutured to the fascial edges with non-absorbable sutures and was removed at definitive abdominal closure. The fasciae were closed with absorbable loops.

VAC-IPOM group

The technique has been previously published [13]. Briefly, patients with OA were treated for one or two cycles with abdominal dressings to stabilize the patients’ conditions. After this initial period, intraperitoneal onlay mesh implantation was performed using dual-layered-, large pore, synthetic meshes. Meshes were placed with an overlap of at least 5 cm on all sides. The meshes were fixed in all corners with a non-absorbable polypropylene suture (Prolene®, Ethicon) and the edges were attached to the peritoneum with the same suture. The fascia was partially or completely closed with a PDS running suture (PDS®, Ethicon). A vacuum dressing (V.A.C.®, KCI) was then placed on the mesh and continuous suction was applied (25–75 mmHg suction). Wound treatment included: (1) vacuum dressings until an adequate formation of granulation tissue was achieved and (2) skin re-adaptation with non-resorbable sutures (Dermalon®, Covidien).

Statistical analysis

Data were reported as median and interquartile ranges (IQR), or numbers and percentages, as appropriate. Patients’ groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test and Mann–Whitney U test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Time-to-event outcomes were analysed using the log-rank test. Effects are reported as risk differences or c-statistics with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The primary endpoint hernia-free survival, was analyzed with Kaplan–Meier curves and a log-rank test for statistical comparison. The effect of mesh treatment on hernia-free survival and secondary outcomes was adjusted in multivariable regression analyses. Clinically important and potential confounder variables (age, gender, BMI, emergency primary operation, malignancy, ASA score, immunosuppressive drugs) were tested in univariable models and included in the multivariable model if the p value was below 0.2. Logistic, Cox or Poisson regression were fitted for binary, time-to-event or count outcomes, respectively. Results were reported as odds ratio (OR), hazard ratio (HR) or incidence risk ratio (IRR) with 95% CI and p values. A two-sided p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS Statistics (Version 17.0.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Meshes used in the VAC-IPOM group include polypropylene-based mesh in 39 (78%) patients, (Parietene composite®, Medtronic, in 34 (87.2%) patients; Dynamesh®, FEG Textiltechnik mbH, in 4 (10.3%) patients; Vipro®, Ethicon, in 1 (2.5%) patient) and polyester-based meshes (Parietex composite®, Medtronic) in 11 (22%) patients. Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics

| VAWCM (n = 89) | VAC-IPOM (n = 50) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median in years (IQR) | 55 (48–67) | 61 (55–72) | 0.046 |

| Male patients (%) | 52 (58.4%) | 30 (60.0%) | 1.000 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 (IQR) | 24.8 (21.0–29.2) | 27.3 (23.1–35.0) | 0.172 |

| Known malignancy (%) | 36 (41.8%) | 27 (54.0%) | 0.212 |

| Type 2 diabetes (%) | 15 (17.0%) | 6 (12.0%) | 0.471 |

| Cardiac disease (%) | 47 (52.8%) | 23 (46.0%) | 0.483 |

| Pulmonary disease (%) | 16 (18.0%) | 20 (40.0%) | 0.008 |

| Liver disease (%) | 18 (20.2%) | 14 (28.0%) | 0.303 |

| Kidney disease (%) | 20 (22.5%) | 9 (18.0%) | 0.665 |

| Anticoagulation preoperative (%) | |||

| Phenprocoumon | 1 (1.2%) | 5 (10.4%) | 0.024 |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors | 5 (6.0%) | 4 (8.3%) | 0.723 |

| Dual anticoagulation | 11 (13.1%) | 2 (4.2%) | 0.132 |

| Immunosuppressors (%) | |||

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 1 (1.2%) | 4 (8.2%) | 0.090 |

| Cortisone | 5 (6.2%) | 2 (4.1%) | |

| Both | 4 (4.9%) | – | |

| ASA score (%) | |||

| 2 | 35 (41.7%) | 8 (16.3%) | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 43 (51.2%) | 18 (36.7%) | |

| 4 | 3 (3.6%) | 22 (44.9%) | |

| 5 | 3 (3.6%) | 2 (4.1%) | |

| Type of primary surgery (%) | |||

| Hepatobiliary surgery | 4 (4.5%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.011 |

| Pancreatic surgery | 6 (6.7%) | – | |

| Upper GI surgery | 14 (15.7%) | 6 (12.0%) | |

| Resection of intestine with preserved continuity | 23 (25.8%) | 9 (18.0%) | |

| Resection of intestine without preserved continuity | 19 (21.3%) | 10 (20.0%) | |

| Pancreatic necrosectomy | 3 (3.4%) | – | |

| Multivisceral resections | 4 (4.5%) | 10 (20.0%) | |

| Vascular surgery | 2 (2.2%) | 4 (8.0%) | |

| Other | 14 (15.7%) | 10 (20.0%) | |

| Emergency primary procedure (%) | 41 (46.1%) | 26 (52.0%) | 0.596 |

| Prior laparotomies, no. (IQR) | 3 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.030 |

| Duration of primary operation in minutes (IQR) | 195 (135–318) | 240 (163–300) | 0.416 |

| Incision at primary procedure (%) | |||

| Median laparotomy | 64 (75.3%) | 49 (98.0%) | 0.007 |

| Transverse Laparotomy | 11 (12.9%) | 1 (2.0%) | |

| Combined | 9 (10.6%) | – | |

| Laparoscopy | 1 (1.2%) | – | |

ASA American Society of Anaesthesiology, IQR interquartile range

Short-term outcome

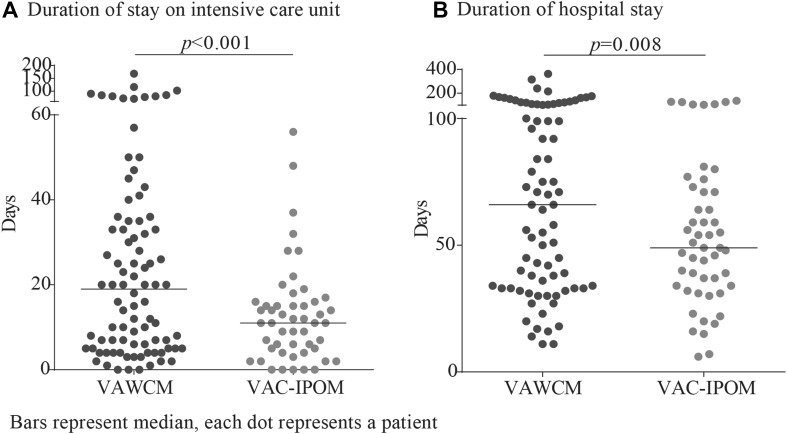

Detailed operative characteristics and postoperative results are shown in Table 2. There was no difference of the intestinal fistula rate and in-hospital mortality between VAWCM and VAC-IPOM. The median number of re-operations after initiation of OA was 5 (IQR 2–13) for VAWCM and 3 (IQR 2–5) for VAC-IPOM (Fig. 1). The incidence of re-operations during hospitalisation per 10-person days after initiation of OA was 1.28 for VAWCM and 0.62 for VAC-IPOM. Therefore, the adjusted incidence risk ratio for re-operation was 0.48 for VAC-IPOM [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.39–0.58, p < 0.001] (Table 3). Duration of ICU stay was significantly longer for VAWCM compared to VAC-IPOM [adjusted hazard ratio 0.53 (CI 95%, 0.36–0.79), p = 0.002] (Fig. 2a). Complete fascial closure was achieved in 66 (74.2%) patients for VAWCM versus 13 (26.0%) patients for VAC-IPOM [risk difference − 48.2 (CI 95%, − 63.3 to − 33.0), p < 0.001]. Duration of hospital stay was significantly longer for VAWCM compared to VAC-IPOM [adjusted hazard ratio 0.61 (CI 95%, 0.40–0.94), p = 0.024] (Fig. 2b).

Table 2.

Operative and postoperative results

| VAWCM (n = 89) | VAC-IPOM (n = 50) | Effect measure (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence of OA after primary surgery in days (IQR) | 11 (4–16) | 11 (7–17) | 0.53 (0.43 to 0.63) | 0.605 |

| Leakage of gastric anastomosis (%) | 5 (5.6%) | 1 (2.0%) | − 3.6 (− 9.8 to 2.5) | 0.419 |

| Leakage of small intestinal anastomosis (%) | 12 (13.5%) | 9 (18.0%) | 4.5 (− 8.3 to 17.3) | 0.471 |

| Leakage of colonic anastomosis (%) | 3 (3.4%) | 5 (10.0%) | 6.6 (− 2.5 to 15.7) | 0.136 |

| Leakage of pancreatic anastomosis (%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0.9 (− 3.6 to 5.3) | 1.000 |

| Leakage of small intestine and colon (%) | – | 1 (2.0%) | 2.0 (− 1.9 to 5.9) | 0.360 |

| VAC therapy (%) | 87 (97.8%) | 45 (90.0%) | − 7.8 (− 16.6 to 1.1) | 0.098 |

| Duration of redo-surgery in minutes (IQR) | 70 (43–110) | 111 (80–181) | 0.72 (0.61 to 0.80) | < 0.001 |

| Incidence of intestinal fistula until 100 days after OA (%) | 16 (18.0%) | 11 (22.0%) | 4.0 (− 10.0 to 18.0) | 0.656 |

| Occurrence of intestinal fistula before OA (%) | 7 (7.9%) | 4 (8.0%) | 0.1 (− 9.2 to 9.5) | 1.000 |

| Intestinal fistula during OA treatment (%) | 9 (10.1%) | 7 (14.0%) | 3.9 (− 7.6 to 15.4) | 0.582 |

| Type of intestinal fistula (%) | ||||

| Small intestine | 13 (14.6%) | 9 (18.0%) | 3.4 (− 9.5 to 16.3) | 0.633 |

| Enteroatmospheric | 3 (3.4%) | 2 (4.0%) | 0.6 (− 6.0 to 7.2) | 1.000 |

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 20 (22.5%) | 9 (18.0%) | − 4.5 (− 18.2 to 9.3) | 0.665 |

| Reason for mortality (%) | ||||

| Cardiopulmonary insufficiency | 2 (2.2%) | – | − 2.2 (− 5.3 to 0.8) | 1.000 |

| Sepsis/multi-organ failure | 12 (13.5%) | 6 (12.0%) | − 1.5 (− 13.0 to 10.0) | 1.000 |

| Underlying disease | 3 (3.4%) | 2 (4.0%) | 0.6 (− 6.0 to 7.2) | 0.633 |

| OtherA | 3a (3.4%) | 1b (2.0%) | − 1.4 (− 6.7 to 4.0) | 1.000 |

| Patients requiring intensive care (%) | 85 (95.5%) | 47 (94.0%) | − 1.5 (−9.4 to 6.4) | 0.702 |

| Days at intensive care unit (IQR) | 20 (6–36) | 11 (6–16) | 0.37 (0.27 to 0.46) | 0.002 |

| Termination of OA treatment after initiation in days (IQR) | 28 (9–63) | 3 (0–7) | 0.13 (0.06 to 0.19) | < 0.001 |

| Fascia closed (%) | 66 (74.2%) | 13 (26.0%) | − 48.2 (− 63.3 to − 33.0) | < 0.001 |

| SSI at discharge (%) | 16 (18.0%) | 27 (54.0%) | 36.0 (20.1 to 52.0) | < 0.001 |

| Duration of hospital stay in days (IQR) | 66 (33–109) | 49 (34–72) | 0.40 (0.3 to 0.49) | 0.007 |

IQR interquartile range, OA open abdomen, SSI surgical site infection

AOther included: a death due to brain oedema (n = 1), pulmonary embolism (n = 1), perforation of aorta (n = 1) and bdeath due to liver failure (n = 1)

Fig. 1.

Re-operations after initiation of open abdomen until discharge

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted effect of mesh-augmentation on important outcome variables

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

| In-hospital mortality | ||||

| VAC-IPOM | 0.76 (0.32–1.82) | 0.534 | 0.45 (0.13–1.61) | 0.221 |

| ASA score > 3 | 2.56 (1.02–6.42) | 0.045 | 3.92 (1.08–14.23) | 0.038 |

| Emergency primary procedure | 2.04 (0.88–4.71) | 0.097 | 3.60 (1.13–11.44) | 0.030 |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 4.72 (1.54–14.46) | 0.006 | 5.14 (1.43–18.44) | 0.012 |

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Intestinal fistula at 100 days | ||||

| VAC-IPOM | 1.29 (0.54–3.04) | 0.566 | 2.06 (0.78–5.42) | 0.143 |

| ASA score > 3 | 0.26 (0.05–1.02) | 0.052 | 0.19 (0.04–0.97) | 0.045 |

| Emergency primary procedure | 0.38 (0.15–0.94) | 0.035 | 0.47 (0.18–1.20) | 0.114 |

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Hernia-free survival | ||||

| VAC-IPOM | 0.30 (0.09–1.02) | 0.055 | 0.36 (0.10–1.27) | 0.114 |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 3.02 (0.87–10.5) | 0.083 | 2.74 (0.78–9.64) | 0.116 |

| Age | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.078 | 0.97 (0.94–1.01) | 0.126 |

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Duration of stay on Intensive care unit | ||||

| VAC-IPOM | 0.52 (0.36–0.77) | < 0.001 | 0.53 (0.36–0.79) | 0.002 |

| Emergency primary procedure | 1.26 (0.89–1.78) | 0.193 | 1.29 (0.88–1.89) | 0.198 |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 1.67 (0.97–2.90) | 0.066 | 1.38 (0.79–2.43) | 0.257 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.034 | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.109 |

| Malignancy | 0.67 (0.47–0.95) | 0.026 | 0.77 (0.53–1.13) | 0.189 |

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Duration of hospital stay | ||||

| VAC-IPOM | 0.57 (0.38–0.87) | 0.008 | 0.61 (0.40–0.94) | 0.024 |

| Age | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.029 | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.115 |

| Malignancy | 0.74 (0.49–1.01) | 0.138 | 0.86 (0.58–1.30) | 0.484 |

| Unadjusted | p | Adjusted | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence risk ratio (95% CI) | Incidence risk ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Re-operations during OA treatment | ||||

| VAC-IPOM | 0.49 (0.41–0.58) | < 0.001 | 0.48 (0.39–0.58) | < 0.001 |

| ASA Score > 3 | 0.70 (0.57–0.85) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (0.82–1.32) | 0.755 |

| Emergency primary procedure | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | 0.090 | 0.89 (0.76–1.04) | 0.134 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.345 |

| Malignancy | 0.69 (0.60–0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.75 (0.64–0.89) | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.117 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.016 |

| Male gender | 0.81 (0.71–0.92) | 0.001 | 0.90 (0.78–1.04) | 0.151 |

Odds ratios, hazard ratios and incidence risk ratios are shown VAC-IPOM versus VAWCM. Variables with a p value below 0.2 on univariable analysis are displayed

Bold values are considered significant (p < 0.05)

95% CI 95% confidence interval; ASA American Society of Anaesthesiology

Fig. 2.

a Duration of stay on intensive care unit. b Duration of hospital stay

Long-term outcome

Median follow-up was 681 days (311–1091) for VAWCM and 426 (178–1058) for VAC-IPOM (p = 0.201). SSI at last follow-up was found in 3 patients for VAWCM [after a median of 648 days (151–1207)] and 12 patients for VAC-IPOM [after a median of 269 days (55–454), p = 0.001]. Hernia-free survival showed a significant curve separation when comparing VAC-IPOM with VAWCM (p = 0.041) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Hernia-free survival

Mesh-related complications

SSI at last follow-up did not differ when comparing polypropylene-based meshes with polyester-based meshes [n = 9 (28.1%) vs n = 3 (33.3%), p = 1.000]. A higher but not significant incidence of SSI was found when fascial closure was not achieved [n = 11 (34.4%)] compared to fascial closure [n = 1 (12.5%), p = 0.240]. Partial mesh explantation due to persistent SSI was necessary in 4 (9.8%) patients. There was no difference in partial mesh explantation when comparing polypropylene-based meshes with polyester-based meshes (n = 3 polypropylene versus n = 1 polyester mesh, p = 1.000). We did not find a difference in incidence of intestinal fistula until 100 days after OA (n = 10 polypropylene versus n = 1 polyester mesh, p = 0.416).

Discussion

The current study shows that VAC-IPOM in patients with OA treatment decrease re-operations, duration of hospital and ICU stay, and the incidence of incisional hernia, when compared with VAWCM, which represents the current standard of care.

OA treatment with temporary abdominal closure should address three main clinical problems: (1) survival of the patient; (2) prevention of short-term complications of the abdominal wall; (3) reduction of long-term complications.

To improve survival and to prevent multi-organ injury in OA, the initial management of abdominal sepsis includes removal of inflammatory ascites [14, 15]. This is mainly achieved by vacuum therapy, which is offered by both, VAC-IPOM and VAWCM and thereby potentially explains the comparable in-hospital mortality.

To reduce short-term complications, the integrity of the abdominal wall should be restored as soon as hemodynamic stabilization and removal of septic foci have been achieved. Repetitive abdominal dressings in this setting as required by VAWCM are potentially unnecessary or even harmful leading to a marked increase in duration of stay on ICU.

The fascial closure rate of the current series with VAWCM was similar to a previously published meta-analysis, i.e., 73.1% [3]. However, the fasciae of 25.8% of patients using the VAWCM technique were not closed and a planned ventral hernia was the consequence, which could be prevented by the VAC-IPOM technique. In the VAC-IPOM group, fascial closure was not required in the majority of patients because this technique was sufficient to stabilize the abdominal wall and prevented excessive fascial traction. Therefore, high tension to achieve fascial closure can be avoided.

Intestinal fistula is a putative complication in patients with OA and might potentially further complicate the clinical course [16]. The current series supports a growing body of literature showing that the incidence of enterocutaneous fistula in the contaminated abdomen is not different when compared to a cohort without synthetic, intraperitoneal mesh implantation [8, 9, 17–19]. Visceral protection with dual-layered meshes seems to be a key element in prevention of mesh-related intestinal fistula in these patients [20]. Because of this additional barrier function, the VAC-IPOM technique also allows bedside subcutaneous VAC treatment, avoiding unnecessary re-operations.

The frequency of SSI in this population is high and may be complicated by chronic mesh infection [21]. Even though mesh removal is a putative complication for chronic SSI (especially in patients with peritonitis), mesh explantation is rarely necessary [22].

At long-term follow-up, incisional hernia is the most important complication in patients after OA [23, 24]. Even in a series of patients with a very high fascial closure rate of 88%, the rate of incisional hernias remained high with an incidence of at least 28.6% [25]. These high incidences of incisional hernia and the fact that the collagen structure is comprised in these patients (Fig. SDC 2) indicates the importance of a reinforcement of the abdominal wall. Biologic meshes are an option for the treatment of abdominal wall defects in contaminated fields [26]. However, a recent meta-analysis revealed that biologic meshes were associated with more surgical site complications and hernia recurrence compared to synthetic meshes [27]. Therefore, usage of biologic meshes for such situations should be critically reevaluated [28].

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and the fact that two different centres were compared with differences in health care. The fact that both hospitals treat a similar number of patients using a comparable surgical spectrum, confounding biases should be reduced. Essentially, prior to data collection, outcome parameters were pre-defined to overcome different definitions. Additionally, the most relevant outcome parameters (Mortality, intestinal fistula, fascial closure, hernia) did not differ compared to other published series [3]. Of note, the current series almost exclusively consists of non-trauma patients.

Conclusion

In the current study, VAC-IPOM in patients with OA decreased re-operations, duration of hospital and ICU stay, and the incidence of incisional hernia compared to VAWCM. Based on these results, abdominal closure using synthetic mesh-augmentation represents a therapeutic option in patients undergoing OA treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

MOJ: Study design, data analysis, writing. CHS: Data collection, data interpretation. TH: Statistical analysis, writing. JZ: Histology, writing. TP: Data collection, data interpretation. DC: Study design, critical revision of the manuscript. PS: Study design, data analysis, critical revision of the manuscript. GB: Study design, data analysis, critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest

MOJ, CHS, TH, JZ, TP, DC, PS and BG declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Cantonal ethics committee of Bern, Switzerland and the institutional review board of the Medical University of Vienna, Austria have approved this study.

Human and animal rights

The study including participant has been performed in accordance with the ethical standard of the Declaration of Helsinki and ist later amendments.

Informed consent

For this retrospective review, informed consent was not required from both ethical review boards.

References

- 1.Coccolini F, Roberts D, Ansaloni L, et al. The open abdomen in trauma and non-trauma patients: WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:7. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0167-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber DG, Bendelli C, Balogh ZJ. Damage control surgery for abdominal emergencies. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e109–e118. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atema JJ, Gans SL, Boermeester MA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the open abdomen and temporary abdominal closure techniques in non-trauma patients. World J Surg. 2015;39:912–925. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2883-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willms A, Schaaf S, Schwab R, Richardsen I, Bieler D, Wagner B, Güsgen C. Abdominal wall integrity after open abdomen: long term results of vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction (VAWCM) Hernia. 2016;20:849–858. doi: 10.1007/s10029-016-1534-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjarnason T, Montgomery A, Ekberg O, Acosta S, Svensson M, Wanhainen A, Björck M, Petersson U. One-year follow-up after open abdomen therapy with vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction. World J Surg. 2013;37:2031–2038. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jairam AP, Timmermans L, Eker HH, et al. Prevention of incisional hernia with prophlyactic onlay and sublay mesh reinforcement versus primary suture only in midline laparotomies (PRIMA): 2-year follow-up of a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390:567–576. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van’t Riet M, de Vos van Steenwijk PJ, Bonjer HJ, Steyerberg EW, Jeekel J. Mesh repair for postoperative wound dehiscence in the presence of infection: is absorbable mesh safer than non-absorbable mesh? Hernia. 2007;11:409–413. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scholtes M, Kurmann A, Seiler C, Candinas D, Beldi G. Intraperitoneal mesh implantation for fascial dehiscence and open abdomen. World J Surg. 2012;36:1557–1561. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1534-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurmann A, Barnetta C, Candinas D, Beldi G. Implantation of prohylactic intraperitoneal mesh in patients with peritonitis is safe and feasible. World J Surg. 2013;37:1656–1660. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:606–608. doi: 10.1017/S0195941700015241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortelny RH, Hofmann A, Gruber-Blum S, Petter-Puchner AH, Glaser KS. Delayed closure of open abdomen in septic patients is facilitated by combined negative pressure wound therapy and dynamic fascial suture. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:735–740. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersson U, Acosta S, Björck M. Vacuum-assisted wound closure and mesh-mediated fascial traction—a novel technique for late closure of the open abdomen. World J Surg. 2007;31:2133–2137. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietz UA, Wichelmann C, Wunder C, Kauczok J, Spor L, Strauss A, Wildenauer R, Jurowich C, Germer CT. Early repair of open abdomen with a tailored two-component mesh and conditioning vacuum packing: a safe alternative to the planned giant ventral hernia. Hernia. 2012;16:451–460. doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0919-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlson GL, Patrick H, Amin AI, McPherson G, MacLennan G, Afolabi E, Mowatt G, Campbell B. Managment of open abdomen: a national study of clinical outcome and safety of negative pressure wound therapy. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1154–1159. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828b8bc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubiak BD, Albert SP, Gatto LA, Snyder KP, Maier KG, Vieau CJ, Roy S, Nieman GF. Peritoneal negative pressure therapy prevents multiple organ injury in a chronic porcine sepsis and ischemia/reperfusion model. Shock. 2010;34:525–534. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e14cd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connolly PT, Teubner A, Lees NP, Anderson ID, Scott NA, Carlson GLl. Outcome of reconstructive surgery for intestinal fistula in the open abdomen. Ann Surg. 2008;247:440–444. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181612c99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birolini C, de Miranda JS, Utiyama EM, Rasslan S. A retrospective review and observations over a 16-year clinical experience on the surgical treatment of chronic mesh infection. What about replacing a synthetic mesh on the infected surgical field? Hernia. 2015;19:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamieh J, Tan WH, Ramirez R, Nohra E, Apakama C, Symons W. Synthetic versus biologic mesh in single-stage repair of complex abdominal wall defects in a contaminated field. Surg Infect. 2017;18:112–118. doi: 10.1089/sur.2016.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carbonell AM, Criss CN, Cobb WS, Novitsky YW, Rosen MJl. Outcomes of synthetic mesh in contaminated ventral hernia repairs. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willms A, Myosoms F, Güsgen C, Schwab R, Lock J, Schaaf S, Germer C, Richardsen I, Dietz U. The open abdomen route by EuraHS: introduction of the data set and initial results of procedures and procedure-related complications. Hernia. 2017;21:279–289. doi: 10.1007/s10029-017-1572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersson P, Montgomery A, Petersson U. Wound dehiscence: outcome comparison for sutured and mesh reconstructed patients. Hernia. 2014;18:681–689. doi: 10.1007/s10029-014-1268-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Argudo N, Pereira JA, Sancho JJ, Membrilla E, Pons MJ, Grande L. Prophylactic synthetic mesh can be safely used to close emergency laparotomy, even in Peritonitis. Surgery. 2014;156:1238–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel NY, Cogbill TH, Kallies KJ, Mathiason MA. Temporary abdominal closure: long-term outcomes. J Trauma. 2011;70:769. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318212785e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandl A, Laimer E, Perathoner A, Zitt M, Pratschke J, Kafka-Ritsch R. Incisional hernia rate after open abdomen treatment with negative pressure and delayed primary fascia closure. Hernia. 2014;18:105–111. doi: 10.1007/s10029-013-1064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verdam FJ, Dolmans DE, Loos MJ, Raber MH, de Wit RJ, Charbon JA, Vroemen JP. Delayed primary fascial closure of the septic open abdomen with a dynamic closure system. World J Surg. 2011;35:2348–2355. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosen MJ, Krpata DM, Ermelich B, Blatnik JA. A 5-year clinical experience with single-staged repairs of infected and contaminated abdominal wall defects utilizing biologic mesh. Ann Surg. 2013;257:991–996. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182849871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atema JJ, de Vries FE, Boermeester MA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the repair of potentially contaminated and contaminated abdominal wall defects. Am J Surg. 2016;212:982–985. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majumder A, Winder JS, Wen Y, Pauli EM, Belyansky I, Novitsky YW. Comparative analysis of biologic versus synthetic mesh outcomes in contaminated hernia repairs. Surgery. 2016;160:828–838. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.