Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and estrogen deficiency both predispose fracture patients to increased risk of delayed union or nonunion. The present study investigated the effects of strontium ranelate (SR) on fracture healing in ovariectomized (OVX) diabetic rats.

Material/Methods

A mid-shaft fracture was established in female normal control (CF), diabetic (DF), and OVX diabetic (DOF) rats. Treated DOF rats received either insulin alone (DOFI) or combined with SR (DOFIS). All rats were euthanized at 2 or 3 weeks after fracture. Fracture healing was evaluated using radiological, histological, immunohistochemical, and micro-computed tomography analyses.

Results

At 3 weeks after fracture, radiological and histological evaluations demonstrated delayed fracture healing in the DF group compared with the CF group, which was exacerbated by OVX, as indicated by the significantly lower X-ray score, BMD, BV/TV, and Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar, and the markedly decreased OCN and Col I expression in the DOF group. All these changes were prevented by insulin alone or combined with SR treatment. In comparison with the DOFI group, DOFIS rats displayed markedly higher OCN expression at 2 weeks after fracture and Col I expression at 2 and 3 weeks after fracture.

Conclusions

These results demonstrated delayed fracture healing with preexisting estrogen deficiency and T2DM. While insulin alone and combined with SR were both effective in promoting bone fracture healing in this model, their combined treatment showed significant improvement in promoting osteogenic marker expression, but not of the radiological appearance, compared with insulin alone.

MeSH Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Fracture Healing; Insulin; Osteoporosis; Strontium

Background

Impaired healing and nonunion of skeletal fractures are global public health problems, with morbidity exacerbated in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), one of the most common chronic diseases, with a growing prevalence as changing lifestyles lead to increased obesity [1,2]. T2DM has been recognized clinically to increase the risk for infection, malunion, nonunion, and re-operation across a wide range of surgically-treated fractures [3]. In addition to diabetes, another common disease in elderly women is postmenopausal osteoporosis, which has also been identified as a possible risk factor for impaired fracture healing [4], indicated by disturbed callus formation and delayed fracture union [5,6].

Fracture healing is a complex process, initiated by an inflammatory response, followed by the formation of soft and hard callus, and ending with callus remodeling and replacement with lamellar bone [7]. This series of biological events follows a specific temporal and spatial sequence that can be affected by factors including abnormal glucose and estrogen levels. T2DM, for example, can increase fracture risk through its specific effects on bone, including high blood glucose levels and an increase in the production of advanced glycation end products, reactive oxygen species, and inflammatory mediators. These factors cause an increase in the number of osteoclasts and a reduction in the number of osteoblasts, leading to an imbalance in bone formation and resorption and, ultimately, an impaired potential for intramembranous and endochondral ossification during fracture repair [8].

Estrogen is the key hormone involved in the maintenance of bone mass, with estrogen deficiency a major cause of postmenopausal osteoporosis due to abnormal bone remodeling and higher bone resorptive activity [9]. Estrogen deficiency can also lead to delayed fracture healing, and callus formation is proved to be related to the expression ratios of different subtypes of estrogen receptors in ovariectomy-induced osteoporotic fracture healing [10]. Previous studies proved that ovariectomy can increase serum glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids [11], and these factors can exacerbate the delayed healing process in diabetes. Moreover, ovariectomized (OVX) rats display clear symptoms of insulin resistance [12]. Therefore, in fracture patients with combined T2DM and postmenopausal osteoporosis, the resulting impaired fracture healing may result in significant morbidity and negatively impact quality of life, leading to a greater economic burden on patients. T2DM and osteoporosis are common and complex disorders that frequently co-exist, particularly in middle-aged and elderly women, with increasing global prevalence. Therefore, there will be a greater requirement for therapy that can accelerate fracture healing in patients with both of these 2 identified high-risk factors of T2DM and postmenopausal osteoporosis, thereby protecting such patients against delayed fracture union and nonunion.

In the clinical setting, patients with T2DM and postmenopausal osteoporosis who sustain a fracture are treated with insulin and anti-osteoporosis agents. Some previous studies have demonstrated that insulin promotes fracture healing. Clinical and experimental studies suggest that strontium ranelate (SR) can improve abnormal bone turnover, as indicated by changes in the levels of circulating bone markers and reduced fracture incidence following treatment [13]. In a normal rat model, SR administration increased the bone volume and microarchitecture as compared with untreated rats. Furthermore, several case reports have shown that SR can both promote bone formation and inhibit bone resorption [14–16]. Additionally, it can promote fracture healing by increasing osteogenesis and bone formation in the fracture site, thereby improving the microstructure of trabecular bone and enhancing the biomechanical properties of the callus [14,17]. Moreover, SR increased the expression of the osteoblast marker osteocalcin (OCN) [14]. We therefore hypothesized that SR would promote fracture healing in rats with estrogen deficiency and T2DM when pre-treated with insulin. In the present study, we evaluated the effect of SR combined with insulin on the healing process of a fracture model in OVX rats with T2DM induced by the consumption of a high-fat diet (HFD) and the injection of a single low dose of streptozotocin (STZ).

Material and Methods

Animals and diet

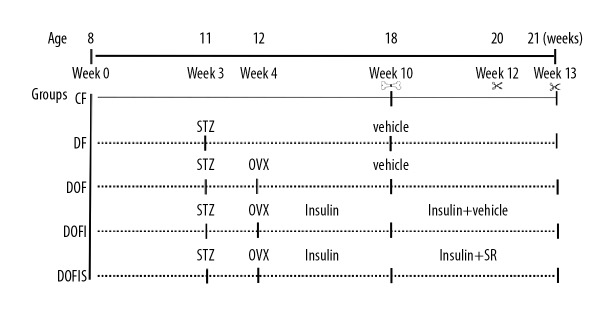

In total, we used 90 8-week-old, female, Sprague-Dawley rats. Prior to this study, all the animals were maintained in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. Sixteen rats were fed a normal diet as the control (CF) group, whereas the remaining rats received an HFD composed of 17% carbohydrate, 41% fat, and 43% protein (catalog number: H10141; Beijing China Fu Kang Biological Technology Co., Ltd.). All of the rats had access to pelleted food and water ad libitum. The feeding methods were retained until the experiment was completed. After 3 weeks of dietary regimen, rats that received the HFD diet were injected with 35 mg/kg STZ (Sigma) dissolved in 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.4, into the abdomen. The blood glucose was determined before and after the injection once weekly. One week after the STZ injection, diabetes was diagnosed when the blood glucose level was >13.9 mmol/L [18]. Following the STZ injection, 6 rats died and 4 rats were excluded from the study after failing to meet the blood glucose level. The remaining 64 rats were randomly divided into 4 experimental groups of 16 rats each: diabetic (DF) group, OVX diabetic (DOF) group, insulin-treated DOF (DOFI) group, and insulin- and SR-treated DOF (DOFIS) group. The rats of the DOFI and DOFIS groups received insulin therapy once diabetes was confirmed. Insulin (Novolin N, Novo Nordisk A/S, Denmark) was injected subcutaneously at 2–4 u during daylight and 4–6 u nightly, adjusted in response to the blood glucose level determined every 2 days [19] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol. Lines: Rats in the CF group were fed a normal chow diet. Dotted lines: Rats in the experimental groups were fed a high-fat diet. STZ: the streptozotocin solution was injected intraperitoneally in DF, DOF, DOFI, and DOFIS groups at 3 weeks. OVX: Rats in the experimental groups (except CF and DF groups) were bilaterally ovariectomized. Insulin: Rats in the DOFI and DOFIS groups were treated with insulin at 4 weeks. All animals underwent closed fracture surgery on the right femur at 10 weeks. Insulin+SR: Rats in DOFIS group were treated with insulin and strontium ranelate until the end of the experiment. Rats were killed at 12 and 13 weeks.

Surgical procedure

The rats in the CF and DF groups underwent a laparotomy, while those in the DOF, DOFI, and DOFIS groups received a bilateral ovariectomy once they met the criteria for diabetes. Penicillin (150 IU/kg, intramuscularly) was administered preoperatively to prevent infection. Following bilateral ovariectomy, the DOFI and DOFIS groups received insulin to control the hyperglycemia symptoms during the entire experiment. After 6 weeks, a standard dropped-weight closed femoral fracture model with intramedullary fixation was used in all cases. Animals were anesthetized using an intraperitoneal injection of 40 mg/kg body weight sodium pentobarbital. Under sterile conditions, a medial parapatellar incision was performed at the right knee. After drilling a hole into the intracondylar, a 20-G needle was implanted intramedullary and the patella was dislocated laterally as described previously [20]. The skin incision was closed using staples. A mid-shaft fracture was established by blunt trauma, using a weight dropped from a height of 30 cm [21]. The fracture was radiographically documented. SR (Servier, Co., France) treatment of 600 mg/kg daily was implemented in the DOFIS group by oral gavage after a closed fracture was established [22]. At 2 or 3 weeks after fracture, rats were euthanized after a 12-h fasting period.

Radiographic analysis

At 2 or 3 weeks after fracture, the rats were anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg), radiographs were obtained in the anteroposterior orientation by high-resolution digital radiography using a DR 7500 system (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, United States) at an exposure of 45 kV for 5.5 s, and the femora were harvested. A radiographic healing score as described previously was assessed independently by 3 observers to grade the fracture healing [23]. The fracture healing was graded as follows: Grade 1, no calcification; Grade 2, patchy-calcification; Grade 3, calcification has the appearance of a callus; Grade 4, callus bridging across the fracture gap; Grade 5, continuity of bone trabeculae; Grade 6, remodeling to normal bone.

Micro-computed tomography (μ-CT)

Formation of new bone was scanned using an isotropic voxel size of 10 μm (55 kVp, 145 μA; μCT 40, Scanco Medical, Brüttisellen, Switzerland). The sample was placed and aligned in parallel in a transparent cylindrical sample holder (18.5 mm diameter) and secured with a surrounding sponge. Regions of interest (ROI) were drawn on the 2-dimensional image slices, with 381 axial slices above and below the fracture gap. The grey-values were globally binarized using the following parameters for callus [sigma (0.8), support (1) and threshold (150)] and cortical bone [sigma (1.5), support (3) and threshold (370)] [24–26]. After reconstruction of the data, the analysis of the non-volume-dependent parameters was performed based on the selected volume of interest to obtain the 3-dimensional interpretation. The threshold applied in the present study used the following parameters for callus and cortical bone. The following measures of bone structure and composition were evaluated from the μ-CT image data for each specimen: bone mineral density (BMD, mg HA/cm3); bone volume (BV, mm3); total volume (TV, mm3); and percent bone volume (BV/TV, 1).

Histology analysis

After micro-CT scanning, the specimens were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and transferred to 0.5 methylenediaminetetraacetic acid (pH 7.4) for 8 weeks. Afterward, the tissues were dehydrated with a series of ethanol rinses and 1 rinse with chloroform, and then were embedded in paraffin. Six-micrometer-thick sections were prepared along the coronal plane of the femur using a microtome (Leica RM2165, Leica, Germany). For the quantitative analysis, all sections were stained by safranin-O/light green. The mineralized area per periosteal callus area: Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar (%) and cartilage area per periosteal callus area: Cg.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar (%) [27] were manually defined by 3 professionals using Image-Pro Plus 6.0.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining

To study the characteristics of TRAP activity, TRAP staining was performed using a staining kit (Leagene, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The area of TRAP staining was quantified by histomorphometry from at least 10 different sites within the callus. The ROI was defined as the area of the callus excluding all cortical bone. This ROI was outlined manually for each specimen using image analysis software [28].

Immunohistochemical analysis

For immunohistochemistry, longitudinal sections of the callus were treated for 10 min at 60°C and processed through xylene and decreasing graded alcohols for hydration. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked using hydrogen peroxide for 15 min. After blocking unspecific binding sites with phosphate-buffered saline and goat normal serum for 30 min at room temperature, trypsin was used to expose the antigen. Immunohistochemical localization of OCN and collagen type-I (Col I) was performed using commercially available specific antibodies. The sections were incubated overnight with a rabbit-anti-rat OCN or Col I monoclonal antibody (1: 500; GTX12496; Dako North America, Inc., Carpinteria, CA, USA) at room temperature. A peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (ZSGB-BIO, PV-6000) was used as secondary antibody (incubation for 30 min at 37°C). Diaminobenzidine (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) served as the chromogen and Mayer’s hemalum as the counterstain, and the sections were washed with distilled water and dehydrated in an increasing graded ethanol and xylene series. To determine the number of positive cells, all sections were evaluated under light microscopy. The percentage of positive cells was determined in 10 randomly selected optical fields from each section by microscopy (×200 magnification). Two sections were selected for each rat. For semi-quantitative analysis, positive cells were defined by yellow-brown granules in the cytoplasm. The ROI was defined as the area of the callus excluding all cortical bone. The semi-quantitative analysis of the immunohistochemical score (IHS) was calculated by combining an estimate of the percentage of immunoreactive cells (A, quantity score) with an estimate of the staining intensity (B, staining intensity score), as follows: A, no positive cells=0, 1–10% positive cells=1, 11–50%=2, 51–80%=3, and 81–100%=4; B: negative=0, weakly positive=1, moderately positive=2, and strongly positive=3 [29].

Statistical analysis

All data are given as means ± standard deviation and were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0. A one-way analysis of variation was performed to analyze all data. Post hoc analysis was performed using an LSD test or Dunnett’s T3 test, as appropriate. A value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

Establishment of animal model

The survival rate of rats treated with the STZ injection was 91.9%, and the success rate for T2DM model establishment was 86.5%. The remaining animals tolerated the fracture procedure well, with limping restricted to 2–4 days during the early post-operative course. One animal in both the DF and DOF groups had to be excluded because of mortality after the fracture operation due to infection complications.

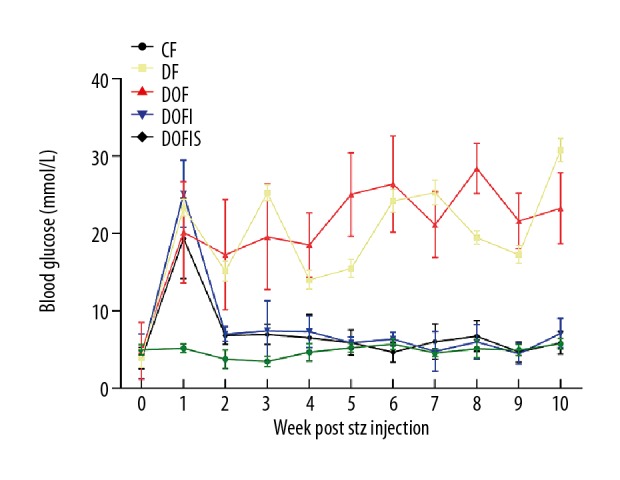

Characteristics of blood glucose

All but the CF group rats received a 3-week HFD, and the blood glucose levels were significantly higher than those of the CF group after a single low-dose STZ injection. The rats treated with insulin with/without SR displayed glucose levels comparable with the CF group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Blood glucose was measured weekly after STZ injection. Data are expressed as mean ±SD.

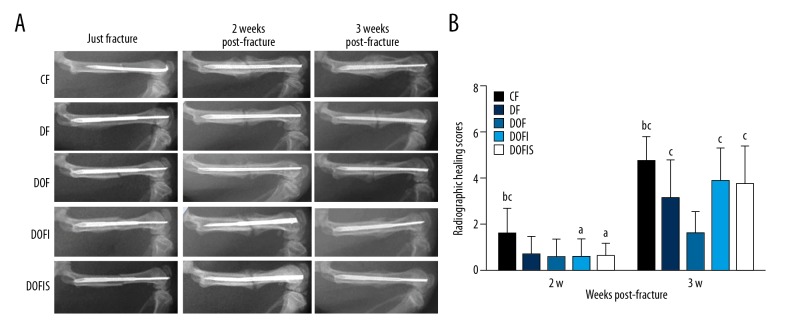

Radiological analysis

Radiological analysis and the healing scores of the 5 groups are presented in Figure 3. At 2 weeks after fracture, the highest fracture healing evaluation score was observed in the CF group, which was significantly higher than in the other 4 groups, while there was no significant difference between the DF and DOF groups nor among the DOF, DOFI, and DOFIS groups.

Figure 3.

(A) Representative radiographies of the 5 groups at 0, 2 and 3 weeks after fracture. (B) Radiographic healing scores of 5 different groups. Data are expressed as mean ±SD. a p<0.05, vs. CF group; b p<0.05, vs. DF group; c p<0.05, vs. DOF group.

At 3 weeks, a clear callus contour was defined in the CF group. The fracture-healing evaluation scores in the DF and DOF groups were significantly lower than that of the CF group, and the healing score in the DOF group was significantly lower than that of the DF group. The DOFI and DOFIS groups displayed significantly higher scores than the DOF group, with no significant difference between the CF, DOFI, and DOFIS groups.

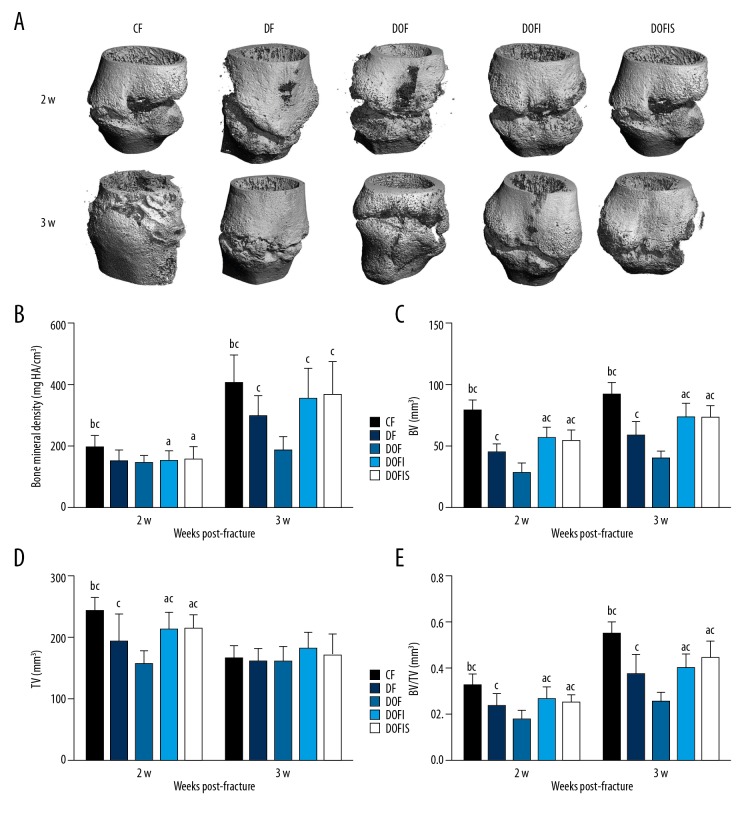

μ-CT

The callus microarchitecture in each group is shown in Figure 4A. At 2 weeks after fracture, the BMD, BV, TV, and BV/TV in the DF and DOF groups were lower than those in the CF group. In addition, the BV, TV, and BV/TV in the DOF group were lower than those in the DF group. By 3 weeks after fracture, the BMD, BV, and BV/TV in the DF and DOF groups were significantly lower than those in the CF group, and those in the DOF group were significantly lower than those in the DF group (Figure 4B–4E).

Figure 4.

(A) The photomicrograph of callus formation and mineralization in fracture area from specimens with micro-CT. Micro-CT analysis of the bone mineral density (B), BV (C), TV (D), BV/TV (E), in the callus of right femoral. Data are expressed as mean ±SD. a p<0.05, vs. CF group; b p<0.05, vs. DF group; c p<0.05, vs. DOF group.

Regarding the effect of insulin alone or in combination with SR treatment, the DOFI and DOFIS groups displayed significantly higher BV, TV, and BV/TV than in the DOF group at 2 weeks after fracture. At 3 weeks after fracture, BMD, BV, and BV/TV in the DOFI and DOFIS groups were higher than those of the DOF group. At 2 weeks after fracture, these 4 parameters in the DOFI and DOFIS groups were significantly lower than in the CF group. At 3 weeks after fracture, similar trends were found in BV and BV/TV, while no statistically significant difference was found in BMD values between CF and DOFI or DOFIS group. When comparing DOFI with DOFIS, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups for these 4 parameters at either 2 or 3 weeks after fracture (Figure 4B–4E).

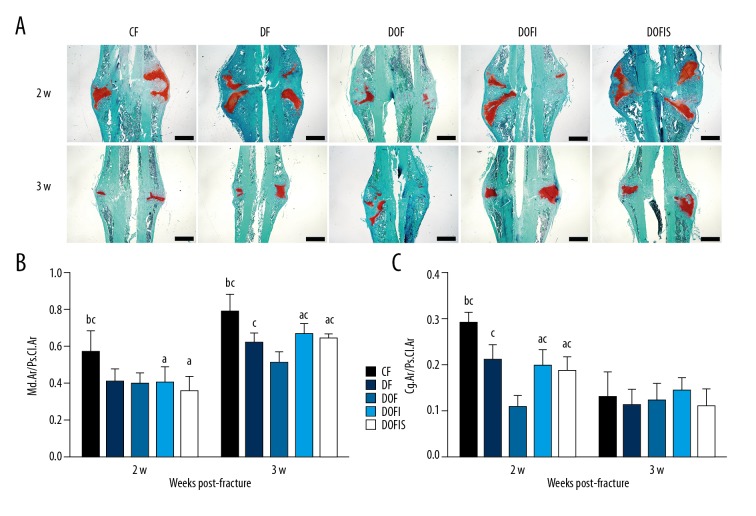

Histology analysis

Histological images of the decalcified sections are presented in Figure 5A. At 2 weeks after fracture, the DF and DOF groups exhibited lower Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar and Cg.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar than in the CF group, with the Cg.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DOF group also lower than in the DF group. At 3 weeks after fracture, the Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DF and DOF groups were lower than in the CF group, and the Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DOF group was lower than in the DF group (Figure 5B, 5C).

Figure 5.

(A) Safranin-O/fast green staining of the longitudinal sections of calluses at 2 and 3 weeks after fracture. Woven bone is stained green and cartilage tissue is red. Black bars=1 mm. (B, C) Comparisons of the mineralized area per periosteal callus area: Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar (%) (B) and cartilage area per periosteal callus area: Cg.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar (%) (C) among the 5 groups. Data are expressed as mean ±SD. a p<0.05 vs. CF group; b p<0.05 vs. DF group; c p<0.05 vs. DOF group.

At 2 weeks after fracture, the Cg.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DOFI and DOFIS groups was larger than that in the DOF group. At 3 weeks after fracture, the Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DOFI and DOFIS groups was significantly larger than in the DOF group. At 2 and 3 weeks after fracture, the Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DOFI and DOFIS groups was lower than in the CF group, and at 2 weeks after fracture, the Cg.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DOFI and DOFIS groups was lower than in the CF group. By contrast, none of these parameters displayed any significant differences between the DOFI and DOFIS groups at either 2 or 3 weeks after fracture (Figure 5B, 5C).

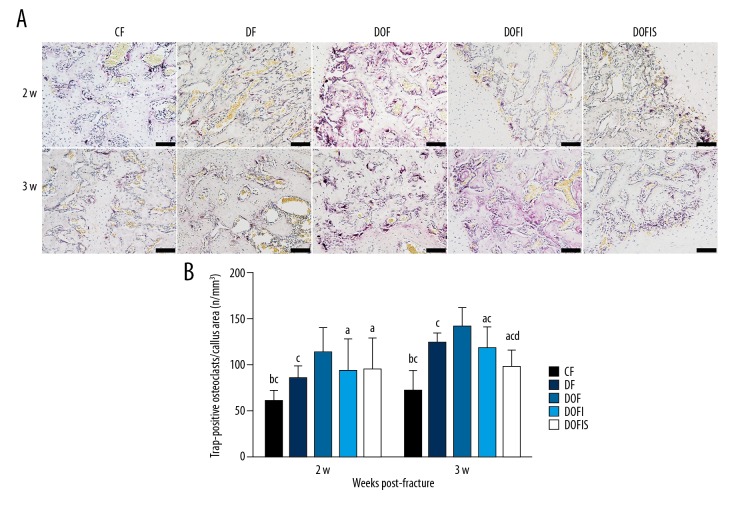

TRAP staining

TRAP-positive multinucleated giant cells were observed in all 5 groups in callus around the newly formed trabeculae, indicating activated bone remodeling (Figure 6A). At 2 and 3 weeks after fracture, new trabecular bone formation by endochondral ossification was observed in the CF group, with little TRAP reaction in the fracture-site callus of CF animals.

Figure 6.

(A) TRAP staining method demonstrating the longitudinal sections of calluses from 2 and 3 weeks after fracture. TRAP-positive multinucleated cells were stained red in the callus. The black bars=100 μm. (B) Trap-positive osteoclasts per callus area of 5 different groups. Data are expressed as mean ±SD. a p<0.05, vs. CF group; b p<0.01, vs. DF group; c p<0.05, vs. DOF group; d p<0.05, vs. DOFI group.

At 2 and 3 weeks after fracture, the number of osteoclasts in the DF, DOF, DOFI, and DOFIS groups were significantly higher than in the CF group, while the DOF group showed significantly increased osteoclasts compared to the DF group. At 2 weeks after fracture, the number of osteoclasts showed no significant difference among the DOF, DOFI, and DOFIS groups. However, the DOFI and DOFIS groups showed significantly fewer osteoclasts than in the DOF group at 3 weeks after fracture, and the value in the DOFIS group was significantly lower than in the DOFI group (Figure 6B).

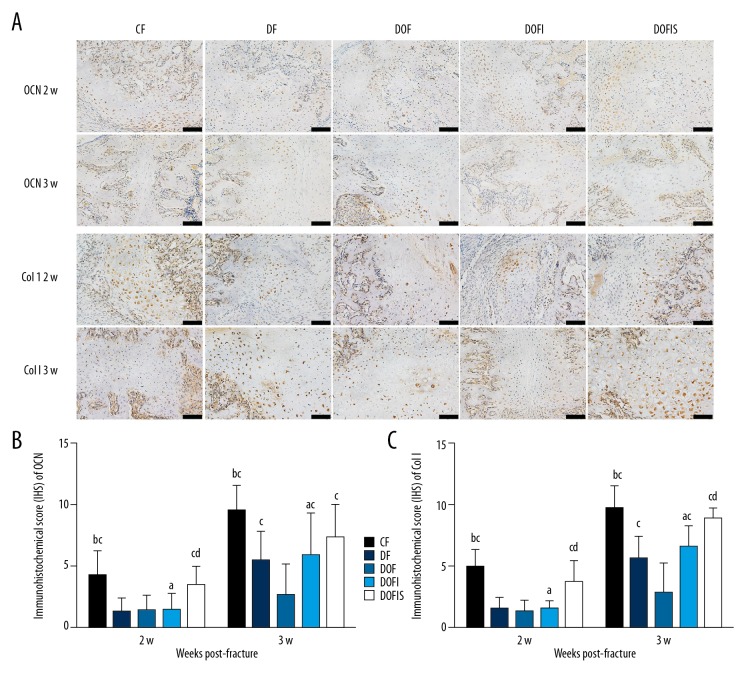

Immunohistochemical staining

The proteins in the callus expressed in the experimental groups are presented in Figure 7A. At 2 and 3 weeks after fracture, the expressions of OCN and Col I in the CF group were higher than in the DF and DOF groups. No significant differences in OCN and Col I staining were found between the DF and DOF groups at 2 weeks after fracture. However, CON and Col I staining in the DF group were significantly greater than in the DOF group at 3 weeks (Figure 7B, 7C).

Figure 7.

(A) Immunohistochemistry staining for OCN and Col I in the callus among the 5 groups. The black bars=100 μm. (B, C) Immunohistochemistry analyses for OCN (B) and Col I (C) in the callus among the 5 groups. Data are expressed as mean ±SD. a p<0.05, vs. CF group; b p<0.01, vs. DF group; c p<0.05, vs. DOF group; d p<0.05, vs. DOFI group.

At 2 weeks after fracture, no significant differences were observed between the DOF and DOFI groups for OCN or Col I. However, the expressions of OCN and Col I in the DOFIS group were significantly greater than in the DOF and DOFI groups. At 3 weeks after fracture, the expressions of OCN and Col I in the DOFI and DOFIS groups were significantly greater than in the DOF group, and the expression of Col I in the DOFIS group was significantly greater than in the DOFI group, but no significant difference was observed between the DOFI and DOFIS groups for OCN. At 2 and 3 weeks after fracture, the expressions of OCN and Col I in the DOFI group were significantly lower than in the CF group. No significant differences were observed between the CF and DOFIS groups for OCN or Col I at either 2 or 3 weeks after fracture (Figure 7B, 7C).

Discussion

The present study provides evidence by radiological, histological, and μ-CT analyses to confirm that preexisting diabetes and estrogen deficiency resulted in delayed fracture healing, while insulin alone or combined with SR promoted fracture healing in this model. However, combined insulin and SR treatment displayed no significant advantage over insulin alone.

The normal fracture healing process in rats was described previously [7]. By 14 days, some of the cartilage begins to calcify, whereas most of the fracture callus remains largely composed of cartilage. By 21 days – corresponding to about 4 or 5 weeks in a human – the fracture is almost united. At this stage, the callus is composed mostly of calcified cartilage, which must be removed and replaced by bone. Previous studies suggested that hyperglycemia in T2DM enhanced and prolonged the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and decreased the expression of osteogenic genes, which in turn can adversely affect bone healing [30–32]. We established a T2DM model using HFD combined with STZ injection [18]. The combined results of all the assessments performed in the present study confirmed that fracture healing was significantly delayed in diabetic rats in comparison with normal rats. This was indicated by a markedly lower X-ray score and bony callus mass and ratio as shown by μ-CT and histology analysis, which are consistent with previous studies [33,34]. A previous study reported that the primary effect of diabetes on cartilage is enhanced loss of cartilage. This may lead to a diminished scaffold for new bone formation, and, hence, a smaller callus size [35]. A similar result was found in the present study: the Cg.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar in the DF group was significantly lower than that in the CF group, with the same trends found for Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar, BV, and BV/TV at 3 weeks after fracture. The expression of OCN and Col I, which are the major proteins released by osteoblasts and contribute greatly to bone formation [36,37], were decreased in the diabetic rats. By contrast, Hie et al. [38] showed that STZ-induced diabetic bone expressed greater TRAP, which is considered to be a characteristic marker of activated osteoclasts. In our study, TRAP staining suggests higher osteoclast activity in the callus of the DF rats. Taken together, the delayed fracture healing process in diabetic rats, with less bone mass of newly formed callus, is due mainly not only to the decreased bone-formation capacity, but also the increased bone-resorption activity.

Estrogen deficiency also induces the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines midkine and interleukin-6 during the early phase after fracture [39] and reduces the differentiation ability of the osteogenic system [40], finally leading to delayed fracture healing [10]. Ferreira et al. [41] demonstrated that bilateral ovariectomy combined with diabetes could exacerbate the disorder of bone microstructure. A further study confirmed that diabetes and estrogen deficiency exacerbated each other’s effect [42]. Li et al. [43] found that the lumbar BMD of OVX rats with T2DM was lower than for OVX or T2DM alone. In the present study, the coexistence of estrogen deficiency exacerbated the delayed fracture-healing process observed in the T2DM rats, particularly at 3 weeks after fracture, indicated by the lower radiographic healing score, BMD, BV, BV/TV, Md.Ar/Ps.Cl.Ar, OCN, and Col I expression, as well as the increased TRAP expression. These results suggest that the preexistence of diabetes and estrogen deficiency more seriously affect the fracture healing process through decreasing the bone formation and increasing bone resorption activity.

Earlier studies proved that insulin treatment can reverse the impaired fracture healing process in diabetic rats by increasing osteoblastic proliferation and enhancing callus mineralization, thereby improving the biomechanical properties of newly formed callus [44–46]. In the present study, insulin treatment displayed beneficial effects on fracture healing in diabetic rats, indicated by the significantly higher X-ray scores than in the DOF group. Moreover, histology and the μ-CT analysis showed enhanced bone mass of the newly formed callus in the insulin-treatment group compared with the DOF group. Interestingly, the X-ray healing score and BMD in the DOFI group are comparable with those in the CF group at 3 weeks after fracture. Previous studies have shown that insulin treatment can reverse the bone loss in newly formed callus [33] and markedly increase femoral BMD in T2DM rats [47]. Moreover, local insulin injections can restore the deficit in cell proliferation in diabetic animals, promote fracture healing, and enhance the formation of mineralized tissues at the defect site [48,49]. These positive effects of insulin on fracture healing in diabetic rats are expected because of its dual roles of modulating glucose metabolism and stimulating the osteogenic process [50]. Increasing evidence indicates that insulin can stimulate osteoblast differentiation, which in turn enhances OCN synthesis, which is the osteoblast-produced peptide that can stimulate pancreatic β-cell proliferation and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity [51]. In the present study, insulin treatment enhanced OCN and Col I expression in the callus of diabetic rats. Moreover, with respect to the potential inhibitory role of insulin on osteoclast activity in this condition [52], we analyzed TRAP in the newly formed callus and found that insulin treatment reduced the osteoclast activity in this model, which can also contribute to its benefits in the fracture-healing process. The evidence presented above indicates that pretreatment with insulin alone promotes the fracture healing process in ovariectomized diabetic rats. However, in the clinical setting, patients with T2DM and postmenopausal osteoporosis who sustain a fracture are most often older patients who have suffered from these conditions for many years, and likely have other complicating factors that contribute to a delay in fracture healing. Although these patients will receive insulin treatment, it is unlikely that it will rescue the fracture healing process as observed in the animal model in the present study.

The effect of SR on bone formation and bone resorption has been proved [53], and increasing evidence from clinical and experimental studies support the effectiveness of SR in enhancing fracture healing [54]. Therefore, SR can be considered an effective therapeutic agent for accelerating fracture healing in osteoporotic bone. However, to date, no study has focused on the effects of SR on fracture healing in rats with combined diabetes and estrogen deficiency. With respect to the clinical treatment strategy assuming that insulin intervention is necessary for diabetic patients, we treated the OVX diabetic rats with either insulin alone or combined with SR, but not SR alone. We found that insulin alone and insulin combined with SR treatment both promoted the fracture-healing process in this model, with enhanced bone mass, increased OCN and Col I expression, and decreased TRAP activity.

However, with the intervention period and dosage used in the present study, we did not find evidence from the radiological, μ-CT, or histologic analysis to prove more significant benefits of SR combined with insulin than that found with insulin treatment alone, because there was no significant difference between the DOFI and DOFIS groups in the healing score. By contrast, TRAP staining and immunohistochemical analysis indicated an increased inhibitory effect of SR on osteoclast activity and promotion of OCN and Col I expression. The contradictory trends between radiological evaluation and biomolecular analysis are difficult to explain. First, they may be due to the short treatment period of 2 or 3 weeks, which for such a complicated model is not long enough to exhibit effects sufficient to convert the molecular benefits into radiological and histologic changes [55]. Second, while the SR dosage of 600 mg/kg/d in the present study can lead to a blood strontium concentration close to the human therapeutic exposure [22], this is a relatively lower dosage when considering the 450–900 mg/kg used in previous studies, where it displayed positive effects on bone formation in bone-defect and fracture models [22, 56–62]. Further study is needed to determine whether a higher SR dose would exhibit a significant effect on fracture healing in the model of combined estrogen deficiency and diabetes. Finally, a previous study indicated that calcium intake and serum calcium levels are important regulators of any SR treatment [63], and that SR and calcium display competing relationships in bone tissue [64]. SR can induce a decrease in the bone-tissue calcium concentration through competing with calcium for deposition in the newly formed bone callus. This may not lead to an obvious adverse effect on the fracture-healing process in rats with a normal diet containing sufficient calcium. However, in the present study, we fed rats with a standard diabetes-inducing diet with 0.4% calcium, which is much lower than the calcium in a normal diet, which may exacerbate the delayed fracture-healing process in this model. With regard to diabetes, this could lead to decreased calcium intake in the gut and increased calcium excretion in the kidneys [65]. All of the factors mentioned above can contribute to the non-significant enhancement of the promotive effects of SR when combined with insulin compared with insulin alone on the fracture-healing process in such a complicated model of fracture established with the preexistence of diabetes and estrogen deficiency.

Conclusions

Multiple factors may be involved in the process of delayed fracture healing caused by diabetes, which is aggravated by estrogen deficiency. With the dosage and intervention regimen in our study, insulin alone partially rescued fracture healing in rats combined with T2DM and estrogen deficiency. Although SR combined with insulin raised the expression of osteogenic-specific markers in the callus, it did not show any additional radiological benefits on new callus compared with insulin alone. Further study with appropriate adjustment of the design is needed to test the potential application of SR in the treatment of menopausal diabetic fracture.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Hong Xu for providing technical and assessment support during immunohistochemical analysis.

Footnotes

Source of support: The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 31171136), the Key Medical Research Foundation of Hebei Province (zd2013092), the Major Project of Nature Science Foundation of Hebei Province (H2016209176), and the Young Talent Support Foundation of Hebei Province

Conflict of interests

None.

References

- 1.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gortler H, Rusyn J, Godbout C, et al. Diabetes and healing outcomes in lower extremity fractures: A systematic review. Injury. 2018;49:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellegaard M, Jorgensen NR, Schwarz P. Parathyroid hormone and bone healing. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;87:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namkung-Matthai H, Appleyard R, Jansen J, et al. Osteoporosis influences the early period of fracture healing in a rat osteoporotic model. Bone. 2001;28:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung WH, Miclau T, Chow SK, et al. Fracture healing in osteoporotic bone. Injury. 2016;47(Suppl 2):S21–26. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(16)47004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Einhorn TA. The science of fracture healing. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:S4–6. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200511101-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiao H, Xiao E, Graves DT. Diabetes and its effect on bone and fracture healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2015;13:327–35. doi: 10.1007/s11914-015-0286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ. Sex steroids and the construction and conservation of the adult skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:279–302. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow SK, Leung KS, Qin L, et al. Callus formation is related to the expression ratios of estrogen receptors-alpha and -beta in ovariectomy-induced osteoporotic fracture healing. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:1405–16. doi: 10.1007/s00402-014-2070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majumdar AS, Giri PR, Pai SA. Resveratrol- and melatonin-abated ovariectomy and fructose diet-induced obesity and metabolic alterations in female rats. Menopause. 2014;21:876–85. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao YK, Zhang SF, Zou SE, Xia X. Daidzein improves insulin resistance in ovariectomized rats. Climacteric. 2013;16:111–16. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.664831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai TT, Tai CL, Ho NY, et al. Effects of strontium ranelate on spinal interbody fusion surgery in an osteoporotic rat model. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167296. e0167296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonnelye E, Chabadel A, Saltel F, Jurdic P. Dual effect of strontium ranelate: Stimulation of osteoblast differentiation and inhibition of osteoclast formation and resorption in vitro. Bone. 2008;42:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi C, Hu B, Guo L, et al. Strontium ranelate reduces the fracture incidence in a growing mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:1003–14. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cianferotti L, D’Asta F, Brandi ML. A review on strontium ranelate long-term antifracture efficacy in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5:127–39. doi: 10.1177/1759720X13483187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahim MR, Singh S, Merican AM, et al. The effect of strontium ranelate on the healing of a fractured ulna with bone gap in rabbit. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12:112. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0724-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivasan K, Viswanad B, Asrat L, et al. Combination of high-fat diet-fed and low-dose streptozotocin-treated rat: A model for type 2 diabetes and pharmacological screening. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki K, Miyakoshi N, Tsuchida T, et al. Effects of combined treatment of insulin and human parathyroid hormone (1–34) on cancellous bone mass and structure in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Bone. 2003;33:108–14. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holstein JH, Menger MD, Culemann U, et al. Development of a locking femur nail for mice. J Biomech. 2007;40:215–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong E, Sangadala S, Boden SD, et al. A novel low-molecular-weight compound enhances ectopic bone formation and fracture repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:454–61. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habermann B, Kafchitsas K, Olender G, et al. Strontium ranelate enhances callus strength more than PTH 1–34 in an osteoporotic rat model of fracture healing. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;86:82–89. doi: 10.1007/s00223-009-9317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quirk BJ, Sannagowdara K, Buchmann EV, et al. Effect of near-infrared light on in vitro cellular ATP production of osteoblasts and fibroblasts and on fracture healing with intramedullary fixation. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2016;7:234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman TA, Patel P, Parvizi J, et al. Micro-CT analysis with multiple thresholds allows detection of bone formation and resorption during ultrasound-treated fracture healing. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:673–79. doi: 10.1002/jor.20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Hsiao EC, Lieu S, et al. Loss of Gi G-protein-coupled receptor signaling in osteoblasts accelerates bone fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:1896–904. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyman JS, Munoz S, Jadhav S, et al. Quantitative measures of femoral fracture repair in rats derived by micro-computed tomography. J Biomech. 2009;42:891–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidmaier G, Wildemann B, Cromme F, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 coating of titanium implants increases biomechanical strength and accelerates bone remodeling in fracture treatment: A biomechanical and histological study in rats. Bone. 2002;30:816–22. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00740-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miao D, Scutt A. Recruitment, augmentation and apoptosis of rat osteoclasts in 1,25-(OH)2D3 response to short-term treatment with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in vivo. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2002;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soslow RA, Dannenberg AJ, Rush D, et al. COX-2 is expressed in human pulmonary, colonic, and mammary tumors. Cancer. 2000;89:2637–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001215)89:12<2637::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blakytny R, Spraul M, Jude EB. Review: The diabetic bone: A cellular and molecular perspective. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2011;10:16–32. doi: 10.1177/1534734611400256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miranda C, Giner M, Montoya MJ, et al. Influence of high glucose and advanced glycation end-products (ages) levels in human osteoblast-like cells gene expression. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:377. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1228-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamann C, Goettsch C, Mettelsiefen J, et al. Delayed bone regeneration and low bone mass in a rat model of insulin-resistant type 2 diabetes mellitus is due to impaired osteoblast function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E1220–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00378.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picke AK, Gordaliza Alaguero I, Campbell GM, et al. Bone defect regeneration and cortical bone parameters of type 2 diabetic rats are improved by insulin therapy. Bone. 2016;82:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creecy A, Uppuganti S, Merkel AR, et al. Changes in the fracture resistance of bone with the progression of type 2 diabetes in the ZDSD rat. Calcif Tissue Int. 2016;99:289–301. doi: 10.1007/s00223-016-0149-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayal RA, Tsatsas D, Bauer MA, et al. Diminished bone formation during diabetic fracture healing is related to the premature resorption of cartilage associated with increased osteoclast activity. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:560–68. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. 2007;130:456–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi J, Hu KS, Yang HL. Roles of TNF-α, GSK-3β and RANKL in the occurrence and development of diabetic osteoporosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:11995–2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hie M, Shimono M, Fujii K, Tsukamoto I. Increased cathepsin K and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase expression in bone of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Bone. 2007;41:1045–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haffner-Luntzer M, Fischer V, Prystaz K, et al. The inflammatory phase of fracture healing is influenced by oestrogen status in mice. Eur J Med Res. 2017;22:23. doi: 10.1186/s40001-017-0264-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goseki MS, Omi N, Yamamoto A, et al. Ovariectomy decreases osteogenetic activity in rat bone. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1996;42:55–67. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.42.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferreira ECS, Bortolin RH, Freire-Neto FP, et al. Zinc supplementation reduces RANKL/OPG ratio and prevents bone architecture alterations in ovariectomized and type 1 diabetic rats. Nutr Res. 2017;40:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verhaeghe J, Suiker AM, Einhorn TA, et al. Brittle bones in spontaneously diabetic female rats cannot be predicted by bone mineral measurements: studies in diabetic and ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1657–67. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650091021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li B, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. Altered gene expression involved in insulin signaling pathway in type II diabetic osteoporosis rats model. Endocrine. 2013;43:136–46. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9757-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beam HA, Parsons JR, Lin SS. The effects of blood glucose control upon fracture healing in the BB Wistar rat with diabetes mellitus. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1210–16. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kayal RA, Alblowi J, McKenzie E, et al. Diabetes causes the accelerated loss of cartilage during fracture repair which is reversed by insulin treatment. Bone. 2009;44:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Follak N, Klöting I, Merk H. Influence of diabetic metabolic state on fracture healing in spontaneously diabetic rats. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2005;21:288–96. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fujii H, Hamada Y, Fukagawa M. Bone formation in spontaneously diabetic Torii-newly established model of non-obese type 2 diabetes rats. Bone. 2008;42:372–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gandhi A, Beam HA, O’Connor JP, et al. The effects of local insulin delivery on diabetic fracture healing. Bone. 2005;37:482–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dedania J, Borzio R, Paglia D, et al. Role of local insulin augmentation upon allograft incorporation in a rat femoral defect model. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:92–99. doi: 10.1002/jor.21205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hou CJ, Liu JL, Li X, Bi LJ. Insulin promotes bone formation in augmented maxillary sinus in diabetic rabbits. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:400–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Paula FJ, Horowitz MC, Rosen CJ. Novel insights into the relationship between diabetes and osteoporosis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:622–30. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas DM, Udagawa N, Hards DK, et al. Insulin receptor expression in primary and cultured osteoclast-like cells. Bone. 1998;23:181–86. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marie PJ. Strontium ranelate: A physiological approach for optimizing bone formation and resorption. Bone. 2006;38:S10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aslam MZ, Khan MA, Chinoy MA, et al. Significance of strontium ranelate in healing of surgically fixed tibial diapyseal fractures treated with strontium ranelate vs. placebo; A randomised double-blind controlled trial. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:S123–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ammann P, Shen V, Robin B, et al. Strontium ranelate improves bone resistance by increasing bone mass and improving architecture in intact female rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:2012–20. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li YF, Luo E, Feng G, et al. Systemic treatment with strontium ranelate promotes tibial fracture healing in ovariectomized rats. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:1889–97. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozturan KE, Demir B, Yucel I, et al. Effect of strontium ranelate on fracture healing in the osteoporotic rats. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:138–42. doi: 10.1002/jor.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zacchetti G, Dayer R, Rizzoli R, Ammanm P. Systemic treatment with strontium ranelate accelerates the filling of a bone defect and improves the material level properties of the healing bone. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/549785. 549785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pérez Núñez MI, Ferreño Blanco D, Alfonso Fernández A, et al. Comparative study of the effect of PTH (1–84) and strontium ranelate in an experimental model of atrophic nonunion. Injury. 2015;46:2359–67. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Komrakova M, Weidemann A, Dullin C, et al. The impact of strontium ranelate on metaphyseal bone healing in ovariectomized rats. Calcif Tissue Int. 2015;97:391–401. doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-0019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosa JA, Sakane KK, Santos KC, et al. Strontium ranelate effect on the repair of bone defects and molecular components of the cortical bone of rats. Braz Dent J. 2016;27:502–7. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201600693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lavet C, Mabilleau G, Chappard D, et al. Strontium ranelate stimulates trabecular bone formation in a rat tibial bone defect healing process. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:3475–87. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pemmer B, Hofstaetter JG, Meirer F, et al. Increased strontium uptake in trabecular bone of ovariectomized calcium-deficient rats treated with strontium ranelate or strontium chloride. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2011;18:835–41. doi: 10.1107/S090904951103038X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fuchs RK, Allen MR, Condon KW, et al. Strontium ranelate does not stimulate bone formation in ovariectomized rats. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1331–41. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wongdee K, Krishnamra N, Charoenphandhu N. Derangement of calcium metabolism in diabetes mellitus: negative outcome from the synergy between impaired bone turnover and intestinal calcium absorption. J Physiol Sci. 2017;67:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s12576-016-0487-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]