Abstract

We identified influenza C virus (ICV) in samples from US cattle with bovine respiratory disease through real-time PCR testing and sequencing. Bovine ICV isolates had high nucleotide identities (≈98%) with each other and were closely related to human ICV strains (≈95%). Further research is needed to determine bovine ICV’s zoonotic potential.

Keywords: influenza C virus, cattle, bovine respiratory disease, BRDC, bovine respiratory disease complex, United States, USA, Midwest, Oklahoma, Montana, Texas, Kansas, Missouri, Colorado, Nebraska, livestock, cows, zoonoses, respiratory infections, viruses, influenza virus, influenza

Influenza viruses are contagious zoonotic pathogens that belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family, which consists of 4 genera: Alphainfluenzavirus (influenza A virus), Betainfluenzavirus (influenza B virus), Gammainfluenzavirus (influenza C virus [ICV]), and Deltainfluenzavirus (influenza D virus) (1–4). Classification of influenza viruses is based on the antigenic differences in the nucleoprotein and matrix protein and supported by intergenic homologies of 20%–30% and intragenic homologies >85% (3).

The most common influenza pathogen is influenza A virus, which can infect humans, pigs, cattle, birds, as well as other animals (2,4). ICV was first identified in humans in 1947. This group of influenza viruses was initially thought to exclusively infect humans until isolates were identified in pigs in China (5,6) and Japan (7). Antigenic and genetic analyses suggest that ICV might transmit between humans and pigs in nature (8); however, interspecies transmission has not been confirmed experimentally. In 2011, an influenza C–like virus was identified in swine and cattle in the United States (9); this virus was initially proposed to be an ICV subtype but was later identified as influenza D virus (3) because the virus had ≈50% overall amino acid identity with human ICV strains, a level of divergence similar to that between influenza A and influenza B viruses.

Although influenza viruses of other genera can infect cattle, the potential for ICV infection in cattle has not been previously investigated. The objective of this study was to determine if ICV can be found in specimens from cattle with bovine respiratory disease and, if so, determine the prevalence.

The Study

Bovine respiratory disease complex (BRDC) is one of the most common causes of death in livestock in US feedlots and feedlots worldwide (10). During October 2016–January 2018, we collected 1,525 samples (mainly nasal swab and lung tissue specimens) from cattle in the Midwest of the United States and submitted them to Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (Manhattan, Kansas, USA) for BRDC diagnostic testing. We screened samples for ICV by real-time reverse transcription PCR, as well as for 10 other BRDC-associated pathogens (Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, Histophilus somni, Bibersteinia trehalosi, Mycoplasma bovis, bovine viral diarrhea virus, bovine respiratory syncytial virus, bovine respiratory coronavirus, bovine herpesvirus 1, and influenza D virus; Technical Appendix). We sequenced a 590-bp fragment of the matrix gene from 12 ICV-positive samples (GenBank accession nos. MH421865–73; Technical Appendix Table) to confirm the PCR results and perform a phylogenetic analysis. We selected 1 isolate (C/bovine/Montana/12/2016) for complete genome sequencing (GenBank accession nos. MH348113–9).

Of 1,525 samples, 64 (4.20%) were positive for ICV: 38 samples with a cycle threshold (Ct) <36 and 26 with a Ct 36–39. The most common pathogens were bovine respiratory coronavirus (34.98%), M. bovis (32.27%), and M. haemolytica (17.04%). The remaining BRDC pathogens were present but less prevalent: P. multocida (13.42%), H. somni (12.58%), influenza D virus (11.93%), bovine respiratory syncytial virus (9.19%), bovine viral diarrhea virus (7.05%), B. trehalosi (3.47%), and bovine herpesvirus 1 (2.95%).

Co-infections with >1 pathogen are common in BRDC cases. ICV-positive samples were also found to be positive for >1 bovine respiratory disease pathogen (n = 12, Table 1), the most common being M. bovis (9/12), followed by H. somni (7/12), and M. haemolytica (6/12). Among the ICV-positive samples, ICV12 was strongly positive (Ct 15.81); this sample was also positive for M. haemolytica and P. multocida, both bacterial pathogens commonly associated with secondary infections. Other BRDC pathogens associated with secondary infections (M. bovis, bovine viral diarrhea virus, and H. somni) were also detected in samples ICV4, ICV16, ICV18, and ICV20 (11–13). These results suggest that ICV is associated with bovine respiratory disease in cattle.

Table 1. Cycle thresholds for ICV and other bovine respiratory pathogens in 12 ICV strong positive samples from cattle with respiratory disease, United States, October 2016–January 2018*.

| ID no. | State | ICV | BVDV | BHV-1 | BRSV | BCoV | IDV | Mycoplasma bovis | Mannheimia haemolytica | Pasteurella multocida | Histophilus somni | Bibersteinia trehalosi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICV1† | TX | 29.95 | – | – | – | – | 36.77 | 39.41 | – | – | – | – |

| ICV2† | OK | 23.92 | – | – | – | – | 24.25 | 29.17 | 31.30 | – | 31.32 | – |

| ICV3† | OK | 21.02 | – | – | 38.93 | 27.00 | 29.15 | 31.40 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| ICV4‡ | OK | 29.98 | – | – | – | – | – | 24.54 | 31.33 | – | 31.05 | – |

| ICV5† | MO | 24.47 | – | 34.98 | – | – | – | 30.12 | – | 28.00 | 24.40 | 34.00 |

| ICV6† | CO | 26.91 | – | – | – | – | – | 30.25 | 32.78 | 29.60 | 30.00 | 35.00 |

| ICV12† | MT | 15.81 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 22.87 | 25.70 | – | – |

| ICV16‡ | NE | 27.18 | 16.44 | – | – | – | – | 28.47 | – | – | – | – |

| ICV18† | MN | 30.58 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 35.06 | – | – | – |

| ICV20‡ | KS | 27.92 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 23.49 | – |

| ICV21‡ | KS | 26.72 | – | – | 35.59 | – | – | 25.67 | 30.95 | – | 28.47 | – |

| ICV22† | MT | 25.08 | – | – | – | – | 20.24 | 35.58 | – | – | 35.64 | – |

*BCoV, bovine respiratory corona virus; BHV-1, bovine herpesvirus 1; BRSV, bovine respiratory syncytial virus; BVDV, bovine viral diarrhea virus; ICV, influenza C virus; ID, identification; IDV, influenza D virus; NT, not tested (sample used up); –, negative. †Nasal swab sample used in analysis. ‡Lung sample used in analysis.

We further evaluated 12 strong positive (Ct<31) samples by sequencing a 590-bp fragment of their matrix gene. Alignment of the partial matrix gene sequences indicated that the isolates in 3 samples (ICV2, ICV3, and ICV4) obtained from different cattle on the same farm in Oklahoma were identical. Because these 3 influenza viruses were most likely the same strain, the virus in just 1 sample (ICV2) was used for phylogenetic analysis. The matrix gene sequence in sample ICV5 from Missouri (GenBank accession no. MH421866) was identical to that in ICV6 from Colorado (GenBank accession no. MH421867).

Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the bovine ICV isolates are closely related to the porcine and human ICV isolates, and the bovine ICV isolates are more closely related to each other (Table 2; Figure). The bovine ICV isolates’ partial matrix gene sequences shared high nucleotide identities (≈98%). For both partial matrix gene sequences and the whole genome sequence (7 segments), the nucleotide identity between bovine and human isolates was ≈95%. The full genome sequence of C/bovine/Montana/12/2016 from sample ICV12 had high nucleotide identity to C/Mississippi/80 (and several other human ICV strains), with an overall identity of 97.1%. Nucleotide identities between these 2 isolates were also high for each gene: 97.0% for polymerase basic 2, 97.7% for polymerase basic 1, 97.5% for polymerase 3, 96.2% for hemagglutininesterase, 96.8% for nucleoprotein, 96.8% for matrix, and 97.6% for nonstructural protein. The only porcine ICV isolate available was more closely related to human (≈98% identity) isolates than bovine (≈95% identity) isolates; the porcine ICV isolate had nearly the same identity that the human ICV isolates had among each other (Table 2).

Table 2. Average nucleotide identities among bovine, porcine, and human ICV strains, United States*.

| Gene sequence | Bovine ICV, % | Human ICV, % | Bovine ICV vs. human ICV, % | Bovine ICV vs. porcine ICV, % | Human ICV vs. porcine ICV, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix, partial | 98.43 | 98.47 | 95.54 | 96.06 | 98.84 |

| Polymerase basic 2 | NA | 97.76 | 94.97 | 95.00 | 98.34 |

| Polymerase basic 1, full length | NA | 97.59 | 94.69 | 94.70 | 98.08 |

| Polymerase 3 | NA | 97.79 | 96.36 | 95.50 | 97.31 |

| Hemagglutinin esterase | NA | 95.44 | 90.83 | 91.10 | 95.97 |

| Nucleoprotein | NA | 97.67 | 95.48 | 95.30 | 97.85 |

| Matrix, complete | NA | 98.33 | 95.51 | 95.80 | 98.82 |

| Nonstructural protein |

NA |

98.32 |

95.67 |

95.80 |

98.36 |

| Entire genome | 97.56 | 94.79 | 94.74 | 97.82 |

*ICV, influenza C virus; NA, not applicable.

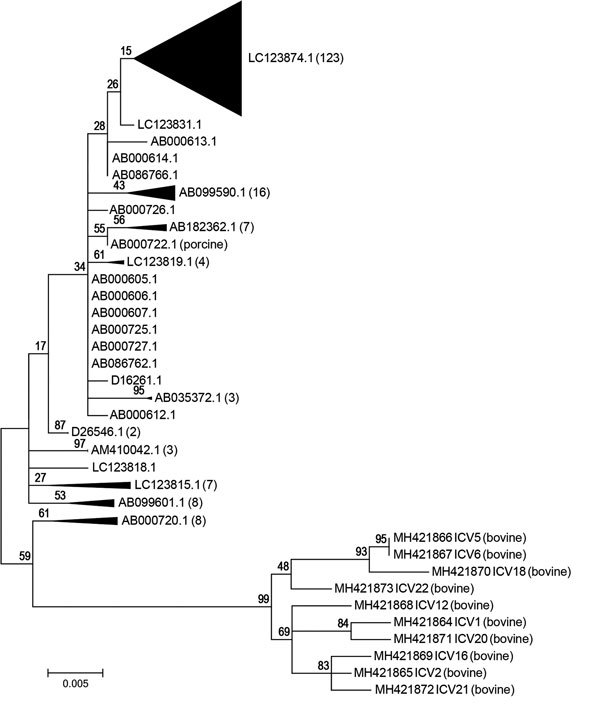

Figure.

Phylogenetic tree of 10 bovine ICV isolates compared with 1 porcine and 195 human ICV isolates (not labeled), United States. Some subtrees containing only human isolates were collapsed to decrease the size of the image. A representative taxon identification number for each collapsed subtree is shown with the number of taxa in the subtree in parentheses. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown above the branches. The tree with the highest log likelihood is shown. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. Scale bar indicates the relative distance of 0.005, which indicates a 0.5% sequence difference. ICV, influenza C virus.

The phylogenetic tree of the partial matrix gene sequences (Figure) further demonstrates the relationship between bovine and human ICV isolates. All bovine ICVs formed a separate clade on the phylogenetic tree, with a 99% bootstrap value. Of the 195 partial matrix gene sequences from human ICVs, the 10 corresponding sequences from bovine ICVs had the highest identities (average 96.70%) to those from C/Mississippi/80 (GenBank no. AB000720.1), C/Nara/82 (GenBank no. AB000723), and C/Kyoto/41/82 (GenBank no. AB000724) and the lowest identities (average 94.21%) to those from C/Yamagata/30/2014 (GenBank no. LC123874) and C/Yamagata/32/2014 (GenBank no. LC123875).

Conclusions

This study confirms the presence of ICV in US cattle with clinical signs of bovine respiratory disease. Although interspecies transmission of influenza viruses occurs between humans and other animals, we do not have data that indicates ICV is a zoonotic pathogen. However, the full genome sequence of C/bovine/Montana/12/2016 has 97.1% nucleotide identity with the human isolate C/Mississippi/80, which is within the range of average identities among human isolates. More detailed investigations are needed to confirm if ICV is involved in bovine respiratory disease, to characterize the relationship between bovine and human ICV strains, and to determine the zoonotic potential of bovine ICV isolates to cause human disease.

Description of methods used for PCR and phylogenetic analysis and bovine influenza C virus sequence information.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and the Swine Health Information Center.

Biography

Mr. Zhang is a joint doctoral student candidate at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Changchun, China, and Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas, USA. His research interests are the development and validation of molecular diagnostic assays for animal and zoonotic pathogens.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Zhang H, Porter E, Lohman M, Lu N, Peddireddi L, Hanzlicek G, et al. Influenza C virus in cattle with respiratory disease, United States, 2016–2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Oct [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2410.180589

References

- 1.King AMQ, Lefkowitz EJ, Mushegian AR, Adams MJ, Dutilh BE, Gorbalenya AE, et al. Changes to taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2018). Arch Virol. 2018;163:2601–31. 10.1007/s00705-018-3847-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spickler AR. Influenza. Flu, grippe, avian influenza, grippe aviaire, fowl plaque, swine influenza, hog flu, pig flu, equine influenza, canine influenza. 2016. [cited 2018 Mar 8]. http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/influenza.pdf

- 3.Hause BM, Collin EA, Liu R, Huang B, Sheng Z, Lu W, et al. Characterization of a novel influenza virus in cattle and Swine: proposal for a new genus in the Orthomyxoviridae family. MBio. 2014;5:e00031–14. 10.1128/mBio.00031-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vemula SV, Zhao J, Liu J, Wang X, Biswas S, Hewlett I. Current approaches for diagnosis of influenza virus infections in humans. Viruses. 2016;8:96. 10.3390/v8040096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo YJ, Jin FG, Wang P, Wang M, Zhu JM. Isolation of influenza C virus from pigs and experimental infection of pigs with influenza C virus. J Gen Virol. 1983;64:177–82. 10.1099/0022-1317-64-1-177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuanji G, Desselberger U. Genome analysis of influenza C viruses isolated in 1981/82 from pigs in China. J Gen Virol. 1984;65:1857–72. 10.1099/0022-1317-65-11-1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaoka M, Hotta H, Itoh M, Homma M. Prevalence of antibody to influenza C virus among pigs in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:711–4. 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimura H, Abiko C, Peng G, Muraki Y, Sugawara K, Hongo S, et al. Interspecies transmission of influenza C virus between humans and pigs. Virus Res. 1997;48:71–9. 10.1016/S0168-1702(96)01427-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hause BM, Ducatez M, Collin EA, Ran Z, Liu R, Sheng Z, et al. Isolation of a novel swine influenza virus from Oklahoma in 2011 which is distantly related to human influenza C viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003176. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Agriculture. Cattle and calves nonpredator death loss in the United States, 2010. 2011 [cited 2018 Mar 8]. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/general/downloads/cattle_calves_nonpred_2010.pdf

- 11.Gabinaitiene A, Siugzdaite J, Zilinskas H, Siugzda R, Petkevicius S. Mycoplasma bovis and bacterial pathogens in the bovine respiratory tract. Vet Med (Praha). 2011;56:28–34. 10.17221/1572-VETMED [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bielefeldt-Ohmann H. The pathologies of bovine viral diarrhea virus infection. A window on the pathogenesis. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 1995;11:447–76. 10.1016/S0749-0720(15)30461-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basqueira NS, Martin CC, dos Reis Costa JF, Okuda LH, Pituco ME, Batista CF, et al. Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) complex as a signal for bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) presence in the herd. Acta Sci Vet. 2017;45:1434. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of methods used for PCR and phylogenetic analysis and bovine influenza C virus sequence information.