Abstract

In a previous study in patients with intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), we found an association between high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) with poor short-term mortality. In the current study, this preliminary finding was validated using an independent patient cohort. A total of 181 ICH patients (from January 2016 to December 2017) were included. Diagnosis was confirmed using computed tomography (CT) in all cases. Patient survival (up to 30 days) was compared between subjects with high NLR (above the 7.35 cutoff; n = 74) versus low NLR (≤ 7.35; n = 107) using Kaplan-Meier analysis. A multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify factors that influenced the 30-day mortality. Correlation between NLR with other relevant factors (e.g., C-reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen) was examined using Spearman correlation analysis. The 30-day mortality was 19.3% (35/181) in the entire sample, 37.8% (28/74) in the high-NLR group, and 6.5% (7/107) in the low-NLR group (P < 0.001). In comparison to the low-NLR group, the high-NLR group had higher rate of intraventricular hemorrhage (29.7 vs. 16.8%), ICH volume (median 23.9 vs. 6.0 cm3) and ICH score (median 1.5 vs. 0), and lower GCS score (9.4 ± 4.5 vs. 12.9 ± 3.2). An analysis that divided the samples into three equal parts based on NLR also showed increasing 30-day mortality with incremental NLR (1.6, 15.0, and 41.7% from lowest to highest NLR tertile, P for trend < 0.001). Kaplan-Meier curve showed higher 30-day mortality in subjects with high NLR than those with low NLR (P < 0.001 vs. low-NLR group, log-rank test). High NLR (> 7.35) is associated with poor short-term survival in acute ICH patients.

Keywords: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, Intracerebral hemorrhage, 30-day mortality, Inflammation

Introduction

Acute intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is associated with high disability and mortality. Increasing evidence suggests that inflammation contributes significantly to tissue damage caused by ICH. Specifically, activated inflammatory cells could release a variety of proinflammatory cytokines and proteases (Zhao et al. 2007), which in turn cause secondary brain injury. Edema, typically the result of inflammatory responses and mechanical compression by hematoma, is a major clinical feature of secondary brain injury and contributes to neurological deterioration (Babu et al. 2012).

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) increases with increasing severity of inflammatory response and has been associated with poor patient outcomes in cancers (Grenader et al. 2016; Ojerholm et al. 2017), cardiovascular diseases (Kurtul et al. 2016; Sari et al. 2015), ischemic diseases (Aktimur et al. 2016; Qun et al. 2017), and a variety of other conditions (Ozcicek et al. 2017; Pan et al. 2017; Senturk et al. 2016). A recent study from this research group (Wang et al. 2016) showed an association of high NLR with 30-day mortality in ICH patients. High NLR has also been suggested to be predictive for 90-day prognosis (Lattanzi et al. 2016b and early neurological deterioration in patients with acute ICH (Lattanzi et al. 2017b). In a study by Lattanzi et al. (2018), NLR improved the accuracy of outcome prediction when added to the Modified ICH score. In patients with ischemic stroke, high NLR has also been associated with bleeding after thrombolysis (Guo et al. 2016). In the current study, we used an independent cohort of ICH patients to validate our previous finding that high NLR (> 7.35) is associated with 30-day mortality in ICH patients.

Methods

Study Sample

Consecutive adult ICH patients receiving treatment for acute ICH at the Emergency Department of Jiading District Central Hospital Affiliated Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences between January 2016 and December 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. The diagnosis of ICH was established with CT scan in all subjects. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study participants

| Inclusion criteria |

| Patients with a diagnosis of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) verified by CT scans. |

| Age ≥ 18 years |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Patients admitted to the hospital > 24 h after ICH. |

| Patients with hematologic disorders, immunosuppressant drug users (steroids), those with a history of infection within 2 weeks before ICH, a stroke history within 6 months, patients with a history of malignancy, and those using anticoagulants. |

| Patients who refused treatment. |

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Jiading District Central Hospital (No.2017-KY-09). All subjects were de-anonymized. Written informed consent was waived by the Ethics Review Board.

Data Collection

Demographic information, past medical history, clinical data, and laboratory measures were collected from medical records. Hypertension was defined using the 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines (Mancia et al. 2014): resting systolic pressure (SBP) at ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic pressure (DBP) at ≥ 90 mmHg on three separate occasions or regular use of anti-hypertension medications. Diabetes was defined using the 2016 American Diabetes Association Guidelines (Chamberlain et al. 2016). All laboratory tests were carried out using venous blood collected after over-night fasting. Patient management was, in principle, based on the 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Guidelines (Hemphill 3rd et al. 2015).

Imaging Analysis

The ICH diagnosis was based on clinical features and confirmed by a post hoc assessment of CT images by an experienced neurologist. The following features were extracted using the CT slice with the largest ICH area: (A) the largest diameter of the hematoma; (B) the dimension of the hemorrhage perpendicular to the largest diameter as the second diameter; (C) the height of the hematoma, as calculated by multiplying the number of slices involved by the slice thickness. ICH volume was calculated as follows: ABC/2 (Kothari et al. 1996). Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) was defined as hyperdense intraventricular signal not attributable to calcification or choroid plexus.

Statistical Analysis

Based on our previous study (Wang et al. 2016), the study sample was divided using NLR at a cutoff of 7.35. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t test if normally distributed and with Mann-Whitney U test if otherwise. Categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 test. Potential association between NLR and 30-day mortality was also assessed by dividing the sample into three parts of equal size followed by P for trend analysis using the Jonckheere-Terpstra test. Spearman correlation analysis was used to determine the correlation of NLR with other factors. Multiple logistic regression was conducted to identify the factors that influenced the 30-day mortality. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

A total of 213 patients with acute ICH sought emergency care at our department during the study period; 32 patients were excluded due to treatment discontinuation within 24 h (n = 19), hospital admission at > 24 h after the first symptom (n = 2), infection within 2 weeks before ICH (n = 5), anticoagulant use within 3 months (n = 5), and leukemia (n = 1). The final analysis included 181 patients (112 men; age 65.8 ± 14.3 years). The mean duration from disease onset to sample collection was 14.8 ± 6.9 h (range: 4–22). The total 30-day mortality was 19.3% (35/181). Demographic data and clinical features are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of all ICH patients included in the study

| Characteristics (n = 181) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years); mean ± SD; (range) | 65.8 ± 14.3 (29~91) |

| Age ≥ 80 years [n (%)] | 39 (21.5) |

| Male [n (%)] | 112 (61.9) |

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 156 (86.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus [n (%)] | 43 (23.8) |

| 30-day mortality [n (%)] | 35 (19.3) |

| Supratentorial origin [n (%)] | 166 (91.7) |

| Presence of IVH [n (%)] | 40 (22.1) |

| ICH volume (cm3); mean ± SD; (range) | 23.8 ± 35.2 (2.3~180.8) |

| GCS score, mean ± SD; (range) | 11.5 ± 4.2 (3~15) |

| ICH score, mean ± SD; (range) | 1.3 ± 1.4 (0~5) |

| Time from ICH onset to sample collect, hours | 14.8 ± 6.9 (4~22) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg); mean ± SD; (range) | 139 ± 15 (92~223) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg); mean ± SD; (range) | 81 ± 16 (57~112) |

| WBC (*109/L); mean ± SD; (range) | 9.6 ± 4.5 (4.6~48.1) |

| Neutrophil (*109/L); mean ± SD; (range) | 7.6 ± 4.5 (0.6~41.4) |

| Lymphocyte (*109/L); mean ± SD; (range) | 1.2 ± 0.5 (0.2~3.3) |

| NLR; mean ± SD; (range) | 8.7 ± 8.6 (1.0~61.9) |

| CRP (mg/L); mean ± SD; (range) | 32.7 ± 8.6 (1.0~198.0) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl); mean ± SD; (range) | 3.6 ± 0.9 (1.4~6.9) |

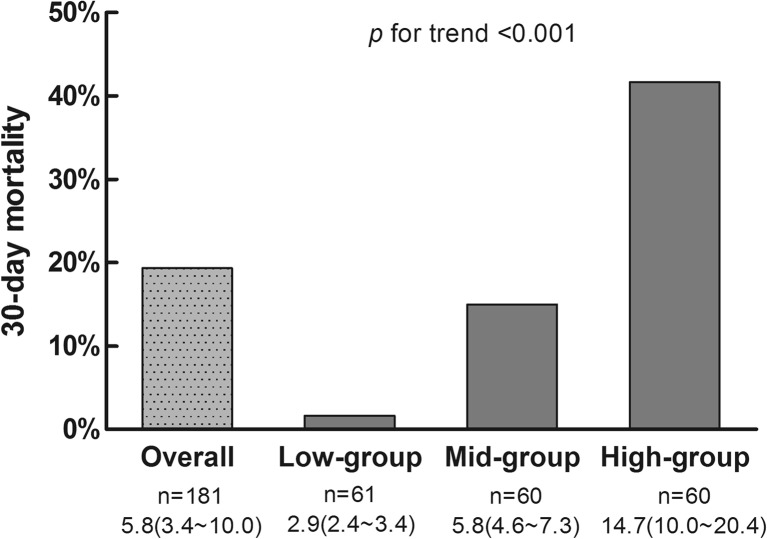

The study sample was divided into three parts of equal size based on NLR: lowest (NLR median: 2.9, 25th~75th: 2.4~3.4), middle (NLR median: 5.8, 25th~75th: 4.6~7.3), and highest (NLR median: 14.7, 25th~75th: 10.0–20.4). The 30-day mortality was 1.6, 15, and 41.7% in the groups with lowest, middle, and highest NLR, respectively (Fig. 1). P for trend was < 0.001.

Fig. 1.

The trend for 30-day mortality with increasing NLR, from the lowest to highest tertile (n = 61 or 60 per tertile). The median value and the 25th~75th are shown under the label of horizon axis

Among the 181 patients, 74 had high NLR (> 7.35); the remaining 107 had low NLR (≤ 7.35). CRP and fibrinogen data were only available in 136 (75%) and 119 (66%) cases out of the 181 total cases, respectively. The 30-day mortality was 37.8% (28/74) in the high-NLR group vs. 6.5% (7/107) in the low-NLR group (P < 0.001). The two groups also differed significantly in the rate of IVH (29.7 vs. 16.8%), ICH volume (median 23.9 vs. 6 cm3), ICH score (median 2 vs. 0), GCS score (9.4 ± 4.5 vs. 12.9 ± 3.2), WBC (median 11.8 × 109/L vs. 8.3 × 109/L), neutrophil count (median 9.7 × 109/L vs. 5.1 × 109/L), lymphocyte count (0.8 × 109/L vs. 1.4 × 109/L), CRP (29 vs. 6 mg/L) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of population with NLR ≤ 7.35 and NLR > 7.35

| Low-NLR group (≤ 7.35, n = 107) |

High-NLR group (> 7.35, n = 74) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years); mean ± SD | 65.0 ± 13.9 | 67.1 ± 14.8 | 0.327 |

| Age ≥ 80 years [n (%)] | 20 (18.7) | 19 (25.7) | 0.261 |

| Male [n (%)] | 65 (60.7) | 47 (63.5) | 0.706 |

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 93 (86.9) | 63 (85.1) | 0.733 |

| Diabetes mellitus [n (%)] | 25 (23.4) | 18 (24.3) | 0.881 |

| Supratentorial origin [n (%)] | 96 (89.7) | 70 (94.6) | 0.242 |

| Presence of IVH [n (%)] | 18 (16.8) | 22 (29.7) | 0.040 |

| ICH volume (cm3); median (IQR) | 6.0 (10.9) | 23.9 (41.3) | < 0.001 |

| GCS score, mean ± SD | 12.9 ± 3.2 | 9.4 ± 4.5 | < 0.001 |

| ICH score, median (IQR) | 0 (1) | 1.5 (2) | < 0.001 |

| Time from ICH onset to sample collection, hours, mean ± SD | 14.0 ± 6.8 | 15.9 ± 7.0 | 0.066 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 157.5 ± 24.2 | 161.5 ± 26.3 | 0.297 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg), mean ± SD | 89.1 ± 14.6 | 95.9 ± 17.0 | 0.005 |

| WBC (*109/L), median (IQR) | 8.3 (4.2) | 11.8 (6.5) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil (*109/L), median (IQR) | 5.1 (2.9) | 9.7 (5.1) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte (*109/L), median (IQR) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.4) | < 0.001 |

| NLR, median (IQR) | 3.7 (2.2) | 11.5 (11.1) | < 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L); median (IQR) | 6 (16.5) | 29 (68.5) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl); mean ± SD | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 0.114 |

| 30-day mortality [n (%)] | 7 (6.5) | 28 (37.8) | < 0.001 |

The Spearman correlation analysis showed an association between NLR with the presence of IVH, ICH volume, GCS score, ICH score, and 30-day mortality as well as CRP (Table 4).

Table 4.

The correlation between NLR, NLR > 7.35, and other factors

| Factors | NLR | NLR > 7.35 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | P | Spearman’s rho | P | |

| Presence of IVH | 0.297 | < 0.001 | 0.166 | 0.026 |

| ICH volume | 0.572 | < 0.001 | 0.474 | < 0.001 |

| GCS score | − 0.533 | < 0.001 | − 0.417 | < 0.001 |

| ICH score | 0.444 | < 0.001 | 0.347 | < 0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 0.454 | < 0.001 | 0.390 | < 0.001 |

| CRP | 0.566 | < 0.001 | 0.487 | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.090 | 0.376 | 0.161 | 0.114 |

We conducted a logistic regression analysis that included NLR (high vs. low), age (≥ 80 years vs. below), IVH (presence vs. absence), ICH volume (≥ 30 cm3 vs. below), GCS score, SBP, DBP, and WBC as independent variables. Selection of the factors was based previously reported association with clinical outcome in ICH patients (Wang et al. 2016; Lattanzi et al. 2016a, b). After adjustment for other factors, high NLR remained to be associated with 30-day mortality, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.797 (95% CI 1.280–11.260) (Table 5). Other factors associated with high mortality included the following: ICH volume ≥ 30 cm3 (OR 2.979, 95% CI 1.012–8.767) and GCS score (OR 0.862, 95% CI 0.755–0.984).

Table 5.

Adjusted risk factors for 30-day mortality in ICH patients

| Variables | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of IVH | 0.003 | 7.249 | 1.983–26.504 |

| ICH volume ≥ 30 cm3 | 0.021 | 15.381 | 1.502–157.493 |

| GCS score | 0.003 | 0.713 | 0.570–0.893 |

| NLR > 7.35 | 0.011 | 8.365 | 1.623–43.110 |

| CRP | 0.081 | 1.014 | 0.998–1.029 |

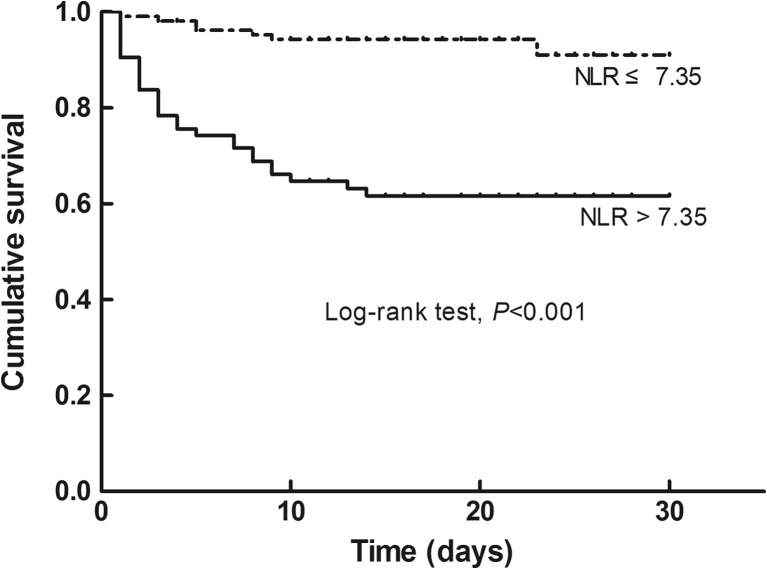

The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that patients with high NLR had significantly higher 30-day mortality than those with low NLR (log-rank test, P < 0.001, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve showing 30-day mortality in subjects with low NLR (≤ 7.35; dotted line; n = 107) vs. high NLR (> 7.35; solid line; n = 74)

Discussion

Previous studies indicated that NLR is closely related to the prognosis of stroke patients (Aktimur et al. 2016; Qun et al. 2017). High NLR is associated with 30-day mortality (Wang et al. 2016) and in-hospital mortality (Giede-Jeppe et al. 2017), as well as 90-day mortality (Lattanzi et al. 2016a, b; Tao et al. 2017) in ICH patients. In patients with ischemic stroke, high NLR has also been associated with hemorrhagic transformation upon thrombolysis (Guo et al. 2016). In the current study, we found a close association of high NLR (> 7.35) with IVH, ICH volume, and ICH score. We also identified a negative correlation between NLR and GCS score. Multivariate logistic regression showed that high NLR is an independent risk for 30-day mortality.

The association between high NLR and short-term mortality is highly complex and could involve many other factors. Upon ICH, neutrophils are the earliest WBCs that appear in hematoma (Wang 2010), peaking in 2–3 days and then gradually disappearing (Wang and Dore 2007; Zhou et al. 2014). Neutrophils release large amounts of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). The concentration of TNF-α in plasma is positively correlated with ICH volume (Behrouz 2016). There is also a positive correlation between the number of TNF-α positive cells and apoptotic neurons around the hematoma (Zhang et al. 2015).

Neutrophils could aggravate brain damage by producing reactive oxygen species, releasing proinflammatory factors, upregulating the expression of metalloproteinase 9, and increasing blood-brain barrier permeability (Moxon-Emre and Schlichter 2011). Neutrophils could also stimulate microglia/macrophages to release a variety of cytokines and free radicals (Wang and Dore 2007). High interleukin-1β (IL-1β) could exacerbate brain edema through inflammatory response and increasing blood-brain barrier permeability (Wei et al. 2014). In a study in animal model of ICH, lymphocytes potentiated cerebral inflammation and brain injury (Rolland 2nd et al. 2011). Fingolimod (Thomas et al. 2017), a drug that reduces T cell cycle pool, could reduce brain edema by downregulating inflammatory mediators, including γ-interferon, IL-17, and expression of intracellular adhesion molecules (Rolland et al. 2013).

Decreased lymphocyte count has been reported to be associated with 90-day mortality (Morotti et al. 2017b) and poor neurological recovery (Giede-Jeppe et al. 2016) in ICH patients. Lower lymphocyte count in non-survivors identified in the current study is consistent with these previous reports. As an established easy-to-use marker of systemic inflammation (Celikbilek et al. 2014), NLR conveys important information about the complex inflammatory activity in the vascular bed (Tamhane et al. 2008).

The current study had several limitations. First, it is an observational, single-institution study with relatively small sample size. Second, we did not examine the relationship between NLR and proinflammatory cytokines. Third, a multitude of variables acts at both local and systemic level to interfere with the pathways linked to the secondary damage and neurovascular recovery (Lattanzi et al. 2013; Lattanzi et al. 2016a; Zangari et al. 2016). Many of these variables were not analyzed in the current study. For example, hematoma growth after ICH has been associated with neuroimaging features (e.g., spot sign (Ciura et al. 2014) and several non-contrast CT markers (Morotti et al. 2017a) as well as blood pressure management (Lattanzi et al. 2017a). Blood pressure variability has been associated with poor clinical outcome both in patients with ischemic stroke (Buratti et al. 2014) and ICH (Lattanzi and Silvestrini 2015; Lattanzi and Silvestrini 2016; Lattanzi et al. 2015). Unfortunately, the current study is based on routine clinical practice in which blood pressure was not measured continuously.

In summary, we found higher 30-day mortality in ICH patients with high NLR (> 7.35). Multivariate regression showed that high NLR is an independent risk for 30-day mortality.

Abbreviations

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- NLR

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- GCS

Glasgow Coma Scale

- IVH

intraventricular hemorrhage

- CT

computed tomography

- SBP

systolic pressure

- DBP

diastolic pressure

- OR

odds ratios

- CI

confidence intervals

- WBC

white blood cells

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

Author Contributions

Fei Wang and Li Wang: carried out the studies, participated in collecting data, and drafted the manuscript. Ting-ting Jiang, Jian-jun Xia, and Wen-hui Kang: participated in collecting data and helped to draft the manuscript. Li-juan Shen: participated in collecting data and tested the blood samples. Feng Xu: performed the statistical analysis. Yong Ding, Li-xia Mei, and Xue-feng Ju: participated in collecting data and followed up patients. Shan-you Hu and Xiao Wu: design, review, and edit the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Information

The work was supported by the Seed Fund (Natural Science Class) of Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences (No. HMSF-17-21-026), Foundation of the Public Health Bureau of Jiading (No. 2017-KY-09) and New Key Subjects of Jiading District (No. 2017-ZD-03).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Shan-you Hu, Phone: 00862167073176, Email: hushanyou9@163.com.

Xiao Wu, Phone: 00862167073128, Email: wx5187@163.com.

References

- Aktimur R, Cetinkunar S, Yildirim K, Aktimur SH, Ugurlucan M, Ozlem N. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a diagnostic biomarker for the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016;42:363–368. doi: 10.1007/s00068-015-0546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu R, Bagley JH, Di C, Friedman AH, Adamson C. Thrombin and hemin as central factors in the mechanisms of intracerebral hemorrhage-induced secondary brain injury and as potential targets for intervention. Neurosurg Focus. 2012;32:E8. doi: 10.3171/2012.1.FOCUS11366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrouz R. Re-exploring tumor necrosis factor alpha as a target for therapy in intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2016;7:93–96. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0446-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratti L, Cagnetti C, Balucani C, Viticchi G, Falsetti L, Luzzi S, Lattanzi S, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Blood pressure variability and stroke outcome in patients with internal carotid artery occlusion. J Neurol Sci. 2014;339:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celikbilek A, Ismailogullari S, Zararsiz G. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis in ischemic cerebrovascular disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 2014;28:27–31. doi: 10.1002/jcla.21639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain JJ, Rhinehart AS, Shaefer CF, Jr, Neuman A. Diagnosis and management of diabetes: synopsis of the 2016 American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:542–552. doi: 10.7326/M15-3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciura VA, Brouwers HB, Pizzolato R, Ortiz CJ, Rosand J, Goldstein JN, Greenberg SM, Pomerantz SR, Gonzalez RG, Romero JM. Spot sign on 90-second delayed computed tomography angiography improves sensitivity for hematoma expansion and mortality: prospective study. Stroke. 2014;45:3293–3297. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giede-Jeppe A, Bobinger T, Gerner ST, Madžar D, Sembill J, Lücking H, Kloska SP, Keil T, Kuramatsu JB, Huttner HB. Lymphocytopenia is an independent predictor of unfavorable functional outcome in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2016;47:1239–1246. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giede-Jeppe A, Bobinger T, Gerner ST, Sembill JA, Sprugel MI, Beuscher VD, Lucking H, Hoelter P, Kuramatsu JB, Huttner HB. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent predictor for in-hospital mortality in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;44:26–34. doi: 10.1159/000468996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenader T, Waddell T, Peckitt C, Oates J, Starling N, Cunningham D, Bridgewater J. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced oesophago-gastric cancer: exploratory analysis of the REAL-2 trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:687–692. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Yu S, Xiao L, Chen X, Ye R, Zheng P, Dai Q, Sun W, Zhou C, Wang S, Zhu W, Liu X. Dynamic change of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and hemorrhagic transformation after thrombolysis in stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:199. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0680-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill JC, 3rd, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, Becker K, Bendok BR, Cushman M, Fung GL, Goldstein JN, Macdonald RL, Mitchell PH, Scott PA, Selim MH, Woo D. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46:2032–2060. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothari RU, Brott T, Broderick JP, Barsan WG, Sauerbeck LR, Zuccarello M, Khoury J. The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke. 1996;27:1304–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.27.8.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtul A, Yarlioglues M, Duran M, Murat SN. Association of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Silvestrini M. Optimal achieved blood pressure in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: INTERACT2. Neurology. 2015;85:557–558. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000470918.40985.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Silvestrini M. Blood pressure in acute intra-cerebral hemorrhage. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:320. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.08.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Silvestrini M, Provinciali L. Elevated blood pressure in the acute phase of stroke and the role of angiotensin receptor blockers. Int J Hypertens. 2013;2013:941783. doi: 10.1155/2013/941783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Blood pressure variability and clinical outcome in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:1493–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Bartolini M, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Glycosylated hemoglobin and functional outcome after acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the outcome of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2016;47:1654–1657. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. How should we lower blood pressure after cerebral hemorrhage? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;43:207–213. doi: 10.1159/000462986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and neurological deterioration following acute cerebral hemorrhage. Oncotarget. 2017;8:57489–57494. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Rinaldi C, Angelocola S, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio improves outcome prediction of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. 2018;387:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology 2013 ESH/ESC practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Blood Press. 2014;23:3–16. doi: 10.3109/08037051.2014.868629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morotti A, Boulouis G, Romero JM, Brouwers HB, Jessel MJ, Vashkevich A, Schwab K, Afzal MR, Cassarly C, Greenberg SM, Martin RH, Qureshi AI, Rosand J, Goldstein JN, ATACH-II and NETT investigators Blood pressure reduction and noncontrast CT markers of intracerebral hemorrhage expansion. Neurology. 2017;89:548–554. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morotti A, Marini S, Jessel MJ, Schwab K, Kourkoulis C, Ayres AM, Gurol ME, Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM, Anderson CD, Goldstein JN, Rosand J. Lymphopenia, infectious complications, and outcome in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2017;26:160–166. doi: 10.1007/s12028-016-0367-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxon-Emre I, Schlichter LC. Neutrophil depletion reduces blood-brain barrier breakdown, axon injury, and inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:218–235. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31820d94a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojerholm E, Smith A, Hwang WT, Baumann BC, Tucker KN, Lerner SP, Mamtani R, Boursi B, Christodouleas JP. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a bladder cancer biomarker: assessing prognostic and predictive value in SWOG 8710. Cancer. 2017;123:794–801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcicek A, Ozcicek F, Yildiz G, Timuroglu A, Demirtas L, Buyuklu M, Kuyrukluyildiz U, Akbas EM, Topal E, Turkmen K. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a possible indicator of epicardial adipose tissue in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:118–123. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.50784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Du J, Li T, Liao H. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio associated with disease activity in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014451. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qun S, Tang Y, Sun J, Liu Z, Wu J, Zhang J, Guo J, Xu Z, Zhang D, Chen Z, Hu F, Xu X, Ge W. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts 3-month outcome of acute ischemic stroke. Neurotox Res. 2017;31:444–452. doi: 10.1007/s12640-017-9707-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland WB, 2nd, Manaenko A, Lekic T, Hasegawa Y, Ostrowski R, Tang J, Zhang JH. FTY720 is neuroprotective and improves functional outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;111:213–217. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0693-8_36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland WB, Lekic T, Krafft PR, Hasegawa Y, Altay O, Hartman R, Ostrowski R, Manaenko A, Tang J, Zhang JH. Fingolimod reduces cerebral lymphocyte infiltration in experimental models of rodent intracerebral hemorrhage. Exp Neurol. 2013;241:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari I, Sunbul M, Mammadov C, Durmus E, Bozbay M, Kivrak T, Gerin F. Relation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio with coronary artery disease severity in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73:1310–1316. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2015.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senturk M, Azgin I, Ovet G, Alatas N, Agirgol B, Yilmaz E. The role of the mean platelet volume and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in peritonsillar abscesses. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamhane UU, Aneja S, Montgomery D, Rogers EK, Eagle KA, Gurm HS. Association between admission neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:653–657. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao C, Hu X, Wang J, Ma J, Li H, You C. Admission neutrophil count and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predict 90-day outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. Biomark Med. 2017;11:33–42. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2016-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K, Sehr T, Proschmann U, Rodriguez-Leal FA, Haase R, Ziemssen T. Fingolimod additionally acts as immunomodulator focused on the innate immune system beyond its prominent effects on lymphocyte recirculation. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:41. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0817-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Preclinical and clinical research on inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:463–477. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Dore S. Inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:894–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Hu S, Ding Y, Ju X, Wang L, Lu Q, Wu X. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and 30-day mortality in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, You C, Jin H, Chen H, Lin B. Correlation between serum IL-1beta levels and cerebral edema extent in a hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage rat model. Neurol Res. 2014;36:170–175. doi: 10.1179/1743132813Y.0000000292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangari R, Zanier ER, Torgano G, Bersano A, Beretta S, Beghi E, Casolla B, Checcarelli N, Lanfranconi S, Maino A, Mandelli C, Micieli G, Orzi F, Picetti E, Silvestrini M, Stocchetti N, Zecca B, Garred P, De Simoni MG, LEPAS group Early ficolin-1 is a sensitive prognostic marker for functional outcome in ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:16. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0481-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yi B, Ma J, Zhang L, Zhang H, Yang Y, Dai Y. Quercetin promotes neuronal and behavioral recovery by suppressing inflammatory response and apoptosis in a rat model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurochem Res. 2015;40:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Sun G, Zhang J, Strong R, Song W, Gonzales N, Grotta JC, Aronowski J. Hematoma resolution as a target for intracerebral hemorrhage treatment: role for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in microglia/macrophages. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:352–362. doi: 10.1002/ana.21097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Anne Stetler R, Yang QW. Inflammation in intracerebral hemorrhage: from mechanisms to clinical translation. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:25–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]