Abstract

In the past decade, new diabetes technologies, including continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) systems, support patients with diabetes in their daily struggle with achieving a good glucose control. However, shortly after the first CGM systems appeared on the market, also the first concerns about adverse skin reactions were raised. Most patients claimed to suffer from (sometimes severe) skin irritation, or even allergy, which they related to the (acrylate-based) adhesive part of the device. For a long time the actual substance that caused these skin reactions with, for example, the Flash Glucose Monitoring system (iscCGM; Freestyle® Libre) could not be identified; however, recently Belgian and Swedish dermatologists reported that the majority of their patients that have developed a contact-allergic while using iscCGM react sensitively to a specific acrylate, that is, isobornyl acrylate (IBOA). Subsequently they showed by means of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry that this substance is present in the case of the glucose sensor attached by an adhesive to the skin. We report three additional cases from Germany, including a 10-year-old boy, suffering from severe allergic contact dermatitis to IBOA.

Keywords: acrylates, adhesives, allergic contact dermatitis, contact allergy, continuous glucose monitoring, flash glucose monitoring, FGM, insulin pump, patch pump, isobornyl acrylate, medical device, patch test

Case Reports

Our index patient, a 10-year-old boy, known with diabetes mellitus type 1 since four years, started usage of the Flash Glucose Monitoring system (iscCGM; Freestyle® Libre, Abbott, Chicago, Ill, US) in May 2016. In November 2016 he complained the first time about an itch underneath the attached glucose sensor, which progressively worsened so that after two days the sensor had to be removed. The skin under iscCGM system was erythematous and vesicular rash was present (Figure 1). The skin reaction subsided after a few days following treatment with a topical corticosteroid cream. The next sensor was then attached upon the other upper arm. However, already within 24 hours he experienced a severe itch again, one day later accompanied from a strong vesicular rash with yellowish secretion at the edges of the sensor, necessitating again its removal. A contact allergy to a component contained in the part connecting the sensor to the skin, was strongly suspected. Interestingly, some weeks later, the patient also unfortunately developed similar skin reactions to the adhesive part of his insulin patch pump (Omnipod®; Insulet/Ypsomed, Liederbach, Germany) possibly to the same, or to a similar, component, the latter then indicating cross-reactivity. Meanwhile, the patient was able to continue to use the iscCGM by using an additional plaster (Stomahesive®, Convatec, Deeside, Flintshire, UK) between the skin and the sensor. This plaster appears to prevent allergens from penetrating into the skin.

Figure 1.

Allergic contact dermatitis in a 10-year-old boy after usage of an iscCGM system.

To verify the hypothesis that a contact allergy was the cause of the skin reaction, patch tests were performed. Patch tests are a well-known diagnostic method where a substance, suspected as the cause of skin allergy (contact allergy), is placed on a test chamber and applied on the back or on the upper arm. These patches are left under occlusion for a certain period, typically 48 hours, after which they are removed again and the tests can be read out and scored (negative [–], doubtful [?], clear [+], strong [++], very strong [+++], and irritant reactions). Readings are usually performed upon removal of the tests, and also one or two days later. In general, a distinction can be made between a contact-irritant and a truly contact-allergic skin reaction. The latter shows a typical crescendo evolution, that is, the patch test reaction becomes stronger over time. Conversely, a contact-irritant skin reaction rather shows a decrescendo reaction pattern.

Patch tests are commercially available and are divided into different patch test trays, designed to diagnose allergic skin reactions in certain patients or within a certain clinical context (eg, hairdressers’ series, rubber series, etc). In our index patient, patch tests were performed with allergens from a ‘standard’ series and from a “plastics and glues” series, following recommendations of the German Contact Allergy Group (Deutsche Kontaktallergie Gruppe; http://dkg.ivdk.org/). The latter test tray also contains some acrylates, which are often present in adhesives, and which are known to be strong sensitizers.

Surprisingly, no reactions were found in the patient, leading us to suspect that other, perhaps non–commercially available acrylates might be contained in the adhesive part of the sensor. To facilitate the diagnostics in this particular case, the adverse skin reaction was reported to the “hotline” of the manufacturer of the iscCGM system, to get more information on the individual components of the system. This approach, however, did not result in a clear response at the first attempt. Thereafter, we contacted the adhesive manufacturer (Adhesive Research Glen Rock, PA, US) which supplies the adhesive materials to the manufacturer of this system. He provided the names of the individual components contained in the adhesive in the framework of a confidentiality agreement. Therefore, this particular information cannot be published. However, after comparing of the acrylates that are in the adhesive with those acrylates contained in the patch test, it becomes clear that most of the acrylates in the adhesive are not present in the patch test.

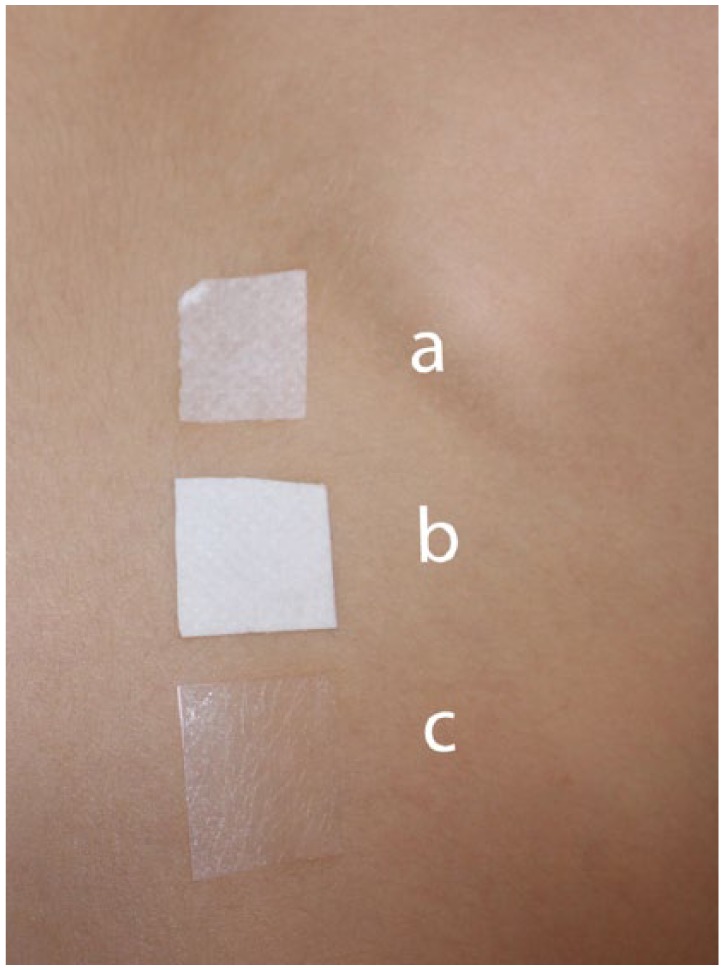

The manufacturer of the adhesive was kind enough to provide those acrylates for further patch testing of the index patient after some months. However, these were not the individual acrylate monomers, but three different (finished) adhesive components from the iscCGM: (a) adhesive that sticks the sensor to the skin; (b) double layer of (a) and (c); (c) only the thin adhesive layer that bounds the plastic case of the glucose sensor to the adhesive. Performance of additional patch tests with these adhesives (Figure 2a) showed surprisingly no skin reactions (Figure 2b). As these results were not in agreement with the strong skin reactions the patient had experienced to the (adhesive part of the) whole glucose sensor device, our hypothesis was that perhaps the true allergen was present in another part of the sensor, possibly migrating toward the skin.

Figure 2a.

Patch tests with the original adhesives obtained from the manufacturer of the adhesive used to attach the glucose sensor to the skin. (a) Adhesive that sticks the sensor to the skin. (b) Double layer. (c) Only the thin adhesive layer that bounds the sensor to the adhesive.

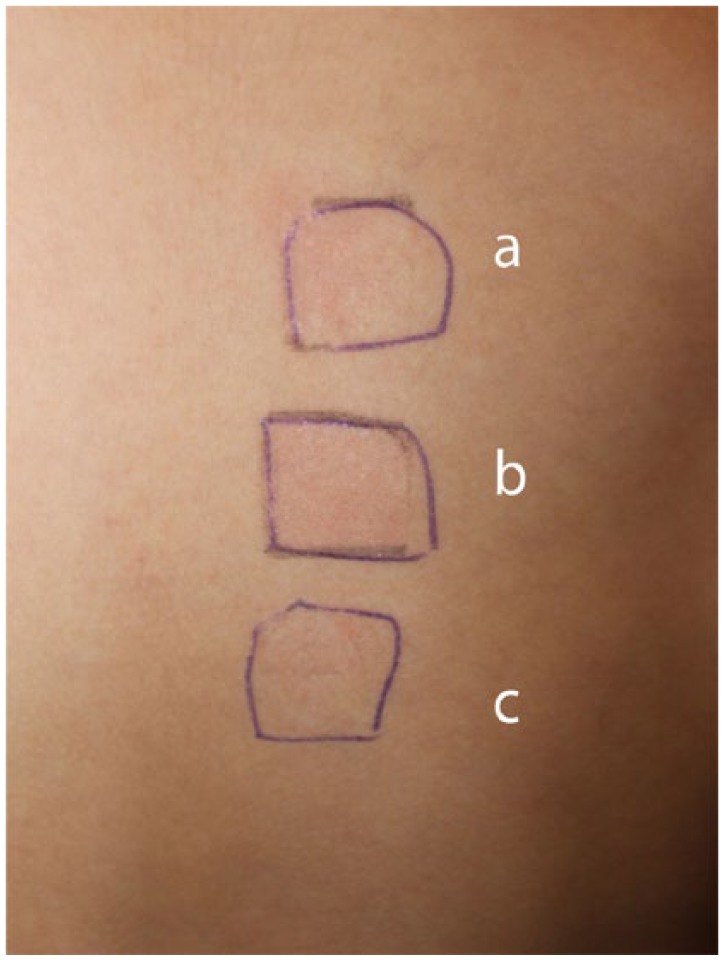

Figure 2b.

No skin reactions to a patch test containing standard acrylates on day 2 and day 3 (shown here).

A recent report by Belgian and Swedish dermatologists showing that several of their patients with skin reactions due to usage of the iscCGM system were sensitized to a specific acrylate (isobornyl acrylate; IBOA).1 An analysis of an extract made from a whole sensor device by means of gas chromatography and mass spectrometry showed that this contains IBOA. Using a small sample of IBOA 0.1% in petrolatum for a patch test in our patient induced a strong skin reaction (Figures 3a and 3b). This also showed the typical crescendo reaction between the two reading times. This argues for a true contact-allergic reaction and excludes a contact-irritant.

Figure 3a.

Positive skin reactions to a patch test reaction (+) containing isobornyl acrylate (IBOA) on day 2.

Figure 3b.

Positive (increased) skin reactions to the same patch test (++) on day 3.

IBOA was also used as a patch test in two other patients with known skin reactions after usage of the iscCGM system. Both have shown no reactions to allergens contained in the standard patch test series, but showed a positive reaction to IBOA. These patients had given written consent before the patch tests were performed.

Discussion

Only limited information exist to how many patients using iscCGM for longer periods of time develop a contact allergy. Obtaining such numbers is difficult as many cases might not be reported to the manufacturer or the authorities. Patients might simply switch to a different CGM system.

One reason for the development of a contact allergy might be the relatively long wearing time of the glucose sensor (ie, in Europe this can be used for two weeks) on the skin. In some patients this may result in skin irritation, but may also lead in others to cutaneous sensitization (contact allergy), and eventually to allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). This was at least reported by dermatologists from Belgium and Sweden,1 and as described in the present three cases from Germany.

Contact allergy is a type IV (cell-mediated) hypersensitivity reaction that typically consists of two phases: The initial phase is the sensitization to an antigen, which may take weeks, but can take months or years to occur. Patients that developed an ACD to the iscCGM system had noticed skin reactions after the use of several sensors. This indicates a sensitization to (a component of) the glucose sensor within a few months; however, some have shown sensitization much sooner (eg, already after the use of one or two sensors). When patients are actually sensitized, the contact-allergic response occurs much faster after reexposure (already within a few days).

Sensitization to an allergen lasts a whole life and cross-reactivity toward chemically related substances may occur (eg, in the case of IBOA, to similar substances present in other medical devices, such as in insulin pumps). No therapy exists to treat contact allergy; the only meaningful action is to avoid exposure to the allergen, or to provide at least a substantial reduction of exposure to it.

Until recently there were only a few reports on skin allergy caused by components of devices used for diabetes therapy.2 In 1995, two young women, who showed a contact-allergic skin reaction to two different insulin pumps were described and the authors revealed that one of the culprit allergens was IBOA.3 A case of sensitization to cyanoacrylate, caused by exposure to a CGM system in another child with diabetes, was recently described.4 In this particular case cyanoacrylate was shown to be a component of the thin layer glue that binds the sensor to the adhesive. The manufacturer of this CGM system (Dexcom®) has already reacted to this adverse event, and has taken the effort to change the construction of their sensor set (Gisin V, JDST, in press). The sensor is now bound onto the adhesive part by a thermic technique, thereby avoiding the further use of cyanoacrylate.

The case described in this article has changed our view about the reason for the development of contact allergies when using the iscCGM system. It appears as if this sensitization is not due to a component (ie, an acrylate) present in the adhesive, or in the thin layer glue between the sensor and the adhesive but to the plastic material of the sensor itself. This view is based on the negative patch tests with commercially available acrylates in our patient, and, furthermore, the negative patch tests with finished adhesive components used in the iscCGM device (before being assembled into the actual complete glucose sensor). The positive skin reactions with patch tests containing IBOA in our patients make us believe that this is the culprit contact allergen in these cases.1 To our understanding IBOA is a part of the plastic material of the glucose sensor themselves. IBOA is an acrylate monomer that can be polymerized and used as a plasticizer, a coating and so on. It has qualities of hardness combined with flexibility, and impact resistance. IBOA can also be easily released into materials flowing over surfaces made from it.5 After recontacting the adhesive manufacturer itself, they once again confirmed that IBOA is not contained in the adhesive part, nor in the layer glue between the adhesive and the sensor.

As medical devices, such as glucose sensors, are not labeled with what kind of material they contain, and as manufacturers tend to be reluctant to handle skin problems caused by their products adequately,1 we speculate that similar issue might have been observed by other dermatology and allergology departments throughout the countries in which iscCGM is widely used already. In a recent study Christoffers et al published an analysis of two decades of occupational patch testing with acrylates in 151 patients.6 The authors also described one case of occupational ACD to IBOA caused by uncured UV ink and acrylate coating.

The cases discussed here make us believe that IBOA is somehow contained in the glucose sensor itself and that this acrylate migrates into the adhesive part of the device and as such comes into contact with the skin. We hope that the information presented here stimulates the manufacturer of iscCGM to investigate this issue further and provide a technical solution for this issue, even if it shows up only in a small fraction of the patients using this product. Longer usage of the iscCGM system in a larger group of patients (also children) might result in skin reactions in a significant number of patients. As there is great interest in continuing usage of this innovative product that is highly appreciated by the patients, our suggestions are intended to improve this system and not to counteract its usage. Our results also indicate that IBOA should become a standard substance for patch tests, used in case of ACD caused by medical devices.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; FGM, flash glucose monitoring; IBOA, isobornyl acrylate.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Herman A, Aerts O, Baeck M, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isobornyl acrylate in Freestyle® Libre, a newly introduced glucose sensor. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;77(6):367-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heinemann L, Kamann S. Adhesives used for diabetes medical devices. A neglected risk with serious consequences? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10(6):1211-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Busschots AM, Meuleman V, Poesen N, Dooms-Goossens A. Contact allergy to components of glue in insulin pump infusion sets. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33(3):205-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwensen JF, Friis UF, Zachariae C, Johansen JD. Sensitization to cyanoacrylates caused by prolonged exposure to a glucose sensor set in a diabetic child. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;74(2):124-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foti C, Romita P, Rigano L, et al. Isobornyl acrylate: an impurity in alkyl glucosides. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2016;35(2):115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christoffers WA, Coenraads PJ, Schuttelaar ML. Two decades of occupational (meth)acrylate patch test results and focus on isobornyl acrylate. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69(2):86-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]