Abstract

There is growing evidence that differentiated care models employed to manage treatment-experienced patients on antiretroviral therapy could improve adherence to medication and retention in care. We conducted a realist evaluation to determine how, why, for whom, and under what health system context the adherence club intervention works (or not) in real-life implementation. In the first phase, we developed an initial program theory of the adherence club intervention. In this study, we report on an explanatory theory-testing case study to test the initial theory. We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis and an explanatory qualitative study to gain insights into the important mechanisms activated by the adherence club intervention and the relevant context conditions that trigger the different mechanisms to achieve the observed outcomes. This study identified potential mitigating circumstances under which the adherence club program could be implemented, which could inform the rollout and implementation of the adherence club intervention.

Keywords: adherence, adherence club, antiretroviral therapy, configurational mapping, intervention-context-actor-mechanism-outcome configuration, generative mechanisms, program theory, realist evaluation, retention in care, retroduction, mixed-methods, South Africa

Background

South Africa has an estimated 7 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (Joint United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS [UNAIDS], 2017), with an estimated 3.5 million (50%) initiated on antiretroviral therapy (ART) as at the end of 2016 (Department of Health, 2016). About 85.5% of HIV-positive South African adults had been diagnosed by mid-2015, but only 56.9% of HIV-diagnosed adults were initiated on ART (Johnson, Dorrington, & Moolla, 2017). Retaining most (90%) of those initiated in care and achieving high population-level adherence to ART (90%) is understood to play a strategic role toward ending AIDS by 2030 (UNAIDS, 2014).

The large cohort of PLWHA on ART in South Africa engenders challenges of poor retention in care (keeping the patients under the care umbrella) and adherence to medication (taking medication at the prescribed time and dose) as the clinics become congested (Bateman, 2013). The congestions experienced at the public health clinic lead to long waiting times, diminished quality of health care, and health care worker fatigue conditions that reduced the willingness of patients to return to the clinic for their required care (L. S. Wilkinson, 2013).

Empirical observations have shown that standard clinic ART service delivery models limit capacities to achieve the UNAIDS’s 2014 “90-90-90” goals (Bateman, 2013). Consequently, differentiated ART delivery models such as the adherence club intervention have been implemented in the Western Cape Province, South Africa, to enhance efforts toward improving retention in care and adherence to ART among PLWHA (MacGregor, McKenzie, Jacobs, & Ullauri, 2018). This is owing to the ability of differentiated models to streamline and decentralize HIV treatment and care services—community-based and home-based models (Grimsrud, Barnabas, Ehrenkranz, & Ford, 2017).

The adherence club intervention was implemented in the Western Cape Province as a systems improvement intervention to enhance patient retention in care, and their adherence to medication, and decongest congested health facilities (Mukumbang, Van Belle, Marchal, & van Wyk, 2016b). The implementation of the adherence club intervention has seen a rapid expansion in the Western Cape Province since its inception in 2007 and subsequent rollout in 2011 (L. Wilkinson et al., 2016). Although the adherence club intervention was originally designed as a clinic-based intervention, various models (community-based and home-based) have been designed to further decentralize (expand) care to the community (International AIDS Society [IAS], 2016).

The adherence club intervention is a differentiated ART delivery model designed to shift the management of PLWHA with a record of good medication adherence and attendance of clinic appointments (stable patients) for group management—health-care worker managed groups or client-managed groups (IAS, 2016). These patients are placed in groups of 25 to 35 and meet bimonthly at the facility (facility-based). The adherence club sessions are facilitated by a lay counselor, who coordinates structured consultations, health talks, group and individual adherence counseling sessions, and medication collections and ensures a conducive environment for social support (Mukumbang, Marchal, Van Belle, & van Wyk, 2018a).

Outcome-based evaluations of the adherence club intervention show that it produces improved rates of retention in care and adherence to medication than the standard clinic ART program (Grimsrud, Sharp, Kalombo, Bekker, & Myer, 2015; Luque-Fernandez et al., 2013; Tsondai et al., 2017). For instance, according to the study conducted by Luque-Fernandez et al. (2013), 2 years after the first enrolment of patients in the adherence clubs, 0.7% had died and 1.7% were lost to follow-up. At the end of the study, 97% of club patients remained in care compared with 85% of patients receiving care via the standard clinic scheme.

The success of group-based adherence-enhancing models of HIV care has led to calls for their adoption within various contexts to improve the management of PLWHA (Grimsrud et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2016). Although evidence suggests that the adherence club intervention is potentially effective for improving medication adherence and retention in care among PLWHA, inciting calls for wide-spread adoption, there is a limited understanding of how, why, and under what health system contexts (conditions) the adherence club intervention could be most effective. In the pursuit of understanding how, why, and under what contexts the adherence club intervention works or not, we proposed a realist evaluation study (Mukumbang, Van Belle, Marchal, & van Wyk, 2016a). In the first phase of the study, we formulated an initial program theory—tentative explanation (Box 1; Mukumbang et al., 2018a).

Box 1.

Initial Program Theory of the Adherence Club Intervention (Hypotheses).

|

Initial Program Theory 1

IF adult (18+ years) clinically “stable” patients with evidence of good clinic attendance are group-managed, receive quick symptom checks, quick access to medication, consistent counseling, and social support from the peer counselor, THEN patients are likely to adhere to medication and remain in care, BECAUSE they develop a group identity, which improves their perceived social support, satisfaction, and trust; and acquire knowledge, which helps them to understand their perceived threat and perceived benefits and improves their self-efficacy. As a result, they become encouraged, empowered, and motivated, thus, more likely to remain in care and adhere to the treatment. Initial Program Theory 2 IF operational staff receive goals and targets set to continuously enroll patients in the adherence club and strictly monitor their participation through strict standard operating practices (the promise of exclusion in the event of missed appointment and active patient tracing), THEN patients are likely to adhere to medication and remain in care, BECAUSE they fear (perceived fear) losing the benefits (easy access to medication, peer support, reduced waiting times, and two-month ART collection) of the club system and they are coerced through adhesive club rules. As a result, they become nudged to remain in care and adhere to the treatment, which might decongest the health facility. |

In this study, we aimed to test the hypothesis (the initial program theory) of the adherence club with the goal of validating, rejecting, or modifying the initial program theory. Our goal, therefore, was to obtain a refined program theory of the adherence club intervention based on the operation of the intervention in the identified primary health care facility.

Methodological Approach

The realist evaluator seeks to understand how, why, for whom, and under what circumstances programs work by formulating program theories (Pawson & Manzano-Santaella, 2012; Pawson & Tilley, 1997, 2004)—how programs achieve their intended outcome(s). The evaluator hypothesizes in advance the intervention (or its components), the relevant actors, mechanisms that are likely to operate, the contexts in which they might operate, and the outcomes that will be observed if they operate as expected. Realist evaluation involves theory testing and refinement; therefore, realist studies start with developing an initial program theory and ends with a refined program theory (Mukumbang, 2018; Mukumbang et al., 2018a).

Realist evaluation explores how causal powers (mechanisms) introduced and/or triggered by the intervention generate outcomes (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). Thus, the process of eliciting and testing the program theory of a program is considered central to the realist evaluation approach. A program theory consists of a set of statements that describes a particular program; explains why, how, and under what conditions the program effects occur; predicts the outcomes of the program, and specifies the requirements necessary to bring about the desired program effects (Sharpe, 2011). Program theory testing assesses whether the assumption(s) of how and why the program is expected to work holds true and under what conditions. If not, why? Therefore, the initial program theory—theories and ideas that inform the design and implementation of the intervention—guides the assessment of the effectiveness of the intervention and the consistency of the implementation (Manzano, 2016).

Pawson and Tilley (1997) proposed the context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) heuristic tool to conceptualize the theory building process in realist evaluation. According to Van Belle, Rifkin and Marchal (2017), “The actors and the interventions are considered to be embedded in a social reality, which influences how the intervention is implemented and how actors respond to it (or not)…” (p. 4) Considering the notions of “actors” and “intervention” in modifying the CMO configuration leads us to the understanding that an outcome (O) is generated by a mechanism (M) being triggered in context (C) through an actor (A) when an intervention (I) is implemented. To this end, we used the intervention-context-actor-mechanism-outcome (ICAMO) configuration as a proposed heuristic explanatory tool to construct the theories in the current study (Mukumbang et al., 2018a).

In our previous work, we formulated the initial program theory of the adherence club intervention. First, we conducted an exploratory qualitative study of program designers’ and managers’ assumptions and perspectives of the intervention and a document review of the design, rollout, implementation, and outcome of the adherence clubs (Mukumbang et al., 2016b). We also conducted a systematic review of available studies on group-based ART adherence support models in sub-Saharan Africa (Mukumbang, Van Belle, Marchal, & van Wyk, 2017a). In addition, we carried out a scoping review of social, cognitive, and behavioral theories that have been applied to explain adherence to ART (Mukumbang, Van Belle, Marchal, & van Wyk, 2017b).

Using the process of configuration mapping—an approach to causality, whereby outcomes are considered to follow from the alignment of a specific combination of attributes (Pawson & Tilley, 2004)—we constructed an ICAMO map representing the initial program theory of the adherence club using the information gleaned from the various sources. We used the “if…then…because” statements to translate the ICAMO configuration map into testable hypotheses (Box 1).

The goal of testing the initial program theory of the adherence club intervention (an evaluation of the adherence club intervention) was to verify, refute, and/or modify the elicited initial program theory. In this study, we report on the process of testing the initial program theory to explicate how, why, for whom, and under what health system context the adherence club intervention could work (or not) in real-life implementation.

Complex interventions, having more than one possible outcomes, sensitive to context, and having long causal chains linking intervention with its outcome(s), such as the adherence club intervention usually undergo some tailoring when implemented in different contexts (Petticrew, 2011). Capturing what is delivered in practice, with close reference to the underlying theory of the intervention, can enable evaluators to distinguish between adaptations to make the intervention fit different contexts and changes that undermine intervention fidelity and realized outcomes (Moore et al., 2015).

Because realist evaluation is focused on providing explanatory models, it has the potential to open the “black box” of programs by making explicit the generative mechanisms to explain how the program modalities lead to the intended outcome(s) (Astbury & Leeuw, 2010). For this reason, realist evaluation is recommended as an alternate approach for capturing the complexities of health care interventions during evaluations (Van Belle, van de Pas, & Marchal, 2017; Van Belle, Rifkin, & Marchal, 2017). Theory-driven approaches to evaluation, such as the realist evaluation, hold the potential to capture the complexities of multi-component interventions and could provide valuable implementation insights of how the different components of the adherence clubs work and under what conditions (Van Belle et al., 2017).

Research Design

Realist evaluation scafolded this explanatory theory–building approach to a multiple embedded case study (Yin, 2013). Facility Z (one of the cases) was considered a unit of analysis, with each of its adherence clubs being subunits. Kœnig (2009) confirmed that the case study research design aligns with the realist evaluation approach.

While conducting a realist evaluation, quantitative data analysis is usually used to identify and classify patterns attributed to the context and program outcome (Westhorp, 2014). Qualitative approaches are, on the contrary, used to explore the context features, the underlining mechanism, and the intervention modalities (Byng, Norman, & Redfern, 2005). In other words, the qualitative methods allow for the identification of the constraints and opportunities the program offers, relevant context elements, the generative mechanisms (reasoning and the choices of the actors), and behaviors of the actors (emergent outcomes).

Study Setting

Facility Z is a provincial primary health care facility that provides primary health care to its surrounding communities. Facility Z provides the first level and some second level care from 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. from Mondays to Fridays. This facility operates as maternity obstetric unit, mental health services, specialized pediatric services for children up to 5 years old, an outpatient department, pharmacy and dispensary, an antiretroviral clinic, and a chronic diseases of lifestyle (CDL) clinic (including CDL clubs). Furthermore, it is an accredited ART initiation and ongoing management site.

The adherence club program was implemented at Facility Z during the first phase rollout of the program in 2011. Three offices situated within the main clinic were allocated for the ART program—for the doctor, nurse, and the counselor(s), respectively. As more patients were recruited into the club program and new clubs were created, the allocated area could no longer accommodate the program. In addition, the ART patients complained of possible identification by their neighbors and friends, so they did not feel comfortable.

Because of these challenges, a project was conceived to build an infectious disease clinic in 2011 to accommodate the ART program. In 2012, the ART program was moved to the new building at the back of the main clinic. This building had four rooms for consultations (one doctor and three nurses), two adherence clubrooms, a waiting area and a storeroom, providing an ideal structural environment for operating the adherence club program.

Following the successes of the adherence club program and the overall ART program at Facility Z, the facility was proposed as the pilot site for the integration of chronic care in 2015. This meant that the ART services had to move back to the main clinic to be situated where the other CDL are being managed to form a single Unit. While the ART patients and those with CDL were managed within the same unit, they were served by separate teams of health care providers with separate treatment management schedules and treatment strategies. The initial challenges of lack of space, inconvenience, and exposure to inadvertent disclosure when managing ART patients resurfaced, so the clinic management decided to move the “integrated” services back to the separate building in 2016 where the services currently (February 2018) operate.

Although the two services are organized within the same unit, they are coordinated separately. On one side, the CDL services operate, and on the other side, the adherence club program, but the patients share a common waiting area. This means that the building that was occupied by the ART services only is being shared with the CDL Unit. Thus, problems of lack of space and confidentiality are prevailing.

Method

Realist evaluation is compatible with a relatively wide range of research methods. Consequently, it is method neutral (does not specify what methods could be used) but encourages the use of a multi-method evidence base (Pawson & Tilley, 2004). Many authors have argued for the systematic combination of qualitative and quantitative methods when conducting realist studies (McEvoy & Richards, 2006). We used qualitative methods to explore implementation features related to the context (nonparticipatory observations) and the mechanism (in-depth interviews), and quantitative methods to describe and classify the outcomes.

Sampling

For the quantitative phase—a retrospective analysis of club registers—we only included the 10 clubs that had reached maximum capacity (25–35) of the 18 clubs that opened in 2012. Of these 10 clubs, we used the lottery or fishbowl draw method of sampling without replacement (Punsalan & Uriarte, 1987) to obtain two adherence clubs to be included in the analysis. Club A had 26 patients and Club B had 34 patients, totaling 60 patients.

Concerning the qualitative phase (interview method), we purposively selected (theoretical sampling) the participants: the health care providers, patients currently using the adherence club intervention, and those who previously were in adherence clubs from the ART department of the primary health care facility. Pawson and Tilley (1997) suggest that the selection of the potential participants for realist interviews should be based on their contributions toward clarifying the initial program theory as different respondents might contribute to different components of the initial program theory. For instance, health care providers have specific ideas on what is in the intervention that works, the outcomes of the intervention, and some awareness of patients for whom the intervention works (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). Patients, on the contrary, are more likely to illuminate the program mechanisms (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). Table 1 shows the number of adherence club patients and cadre sampled to participate in the qualitative arm of the study.

Table 1.

Interview Participants.

| Stakeholder | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Doctors | 1 |

| Adherence club nurse | 2 |

| Adherence club counselors/club facilitator | 2 |

| Patients in clubs | 5 |

| Former club patients | 2 |

| Total | 12 |

Data Collection Strategy and Processes

The data strategy adopted for the study is outlined in Figure 1. The data were collected from November 2016 to April 2017.

Figure 1.

Data collection approach adopted.

We started by collecting quantitative data from the adherence club registers to report on the relevant outcomes and the outcome trends of the adherence club intervention. In Table 2, the various modalities of retention in care as reported in the club register are described.

Table 2.

Various Outcomes of Patients Recorded in the Club Register.

| Recorded Outcome | Outcome Event |

|---|---|

| DNA | Did not attend—Club session or send a buddy within 5 days after the club sessions |

| BTC | Back to Clinic—Exiting the club for medical reasons and reinstated in the routine standard of care |

| TFOC | Transferred out to a different club—Patient is transferred out to another club in the same facility |

| TFO | Transfer out—Patient is leaving the facility completely and will attend a clinic elsewhere |

| RIP | Rest in Peace—Patient has died |

In addition, viral load data of the patients attending the adherence club are recorded in the adherence club register. The notation LDL (lower than detectable) is used to indicate viral repression. Therefore, we used the “time to first viral rebound (<400 copies/mL)” as an indication of poor adherence to medication.

For the qualitative phase, we applied three data collection methods: nonparticipant observations of adherence club sessions and activities, semistructured interviews with the clinicians and the facility counselors, and in-depth interviews with patients using the adherence club interventions. In some instances, we conducted dyadic interviews (Morgan, Ataie, Carder, & Hoffman, 2013)—where we allowed two participants of the same designation (i.e., counselors) to interact in response to interview questions.

We scheduled the structured observations to align with the bimonthly adherence club scheduled meetings. An observation guide (Supplementary Appendix 1) detailing the interactions, processes, or behaviors to be observed before, during, and after the adherence club session was used. We conducted two structured observations per club as illustrated in Figure 1.

In the interviews, the initial program theories were presented to the participants, and they were requested to respond to alternate theories—confirming, falsifying, and, above all, refining the initial program theories (Manzano, 2016). In applying this method, we used a semistructured interview format guided by an interview guide (Supplementary Appendix 2). As required in realist interviewing, we tailored the interview questions to reflect the knowledge held by the various participants. For the operational staff, our focus was on the implementation and outcomes of the adherence club intervention. The focus of the patient interview was to guide the patients to recount their experiences and reasoning related to their context.

Quantitative data were captured and prepared for analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 24. The structured observations were documented in the form of jottings and photos, which were later developed into field notes. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber and prepared for analysis. Atlas.ti version 7 was used to manage the qualitative data.

Ethical Considerations

This study is part of a larger project, “A Realist Evaluation of the Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence Club Program in Selected Primary Health-Care Facilities in the Metropolitan Area of Western Cape Province, South Africa.” Ethics clearance was received from the University of the Western Cape Research Ethics Committee (UWC REC; Registration No: 15/6/28; Mukumbang et al., 2016a). We also obtained permission from the Provincial Department of Health of the Western Cape Province. In addition, we obtained the permission of the facility head and management prior to data collection processes.

At the level of the study participants, we first provided the interviewed participants with an information sheet of the project. This was followed by a verbal explanation of the role of the participant—taking part in an interview for 20 to 30 minutes—and the significance of their participation. The participants were required to sign an informed consent form. We promised and ensured confidentiality and anonymity by identifying the participants using pseudo names and by password-protecting all files related to the study.

To access the adherence and retention in care records of the patients from the club registers, permission was obtained from the clinic manager and the head of the adherence club unit. Access to the data was also monitored by two adherence club counselors and the data clerk involved the sampling process.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (Bland & Altman, 1998) to estimate the probability of being retained in care at 12, 24, and 36 months intervals. Participants were considered not retained in the club care if lost to follow-up, sent back to clinic care, or died. Time to first viral rebound (<400 copies/mL) was used to assess their adherence behavior.

Thematic content analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994) of the qualitative data was conducted using the ICAMO heuristic framework (Table 3). This process involved identifying what data elements could be categorized as Intervention modality, Context elements, Actor attributes, and generative Mechanisms and Outcome patterns through a deductive process guided by the two initial program theories.

Table 3.

Thematic Content Analysis Coding Frame.

| Category | Definition | Coding Rules |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | An intervention is a combination of program elements or strategies designed to produce behavior changes or improve health status among individuals or a group | Modalities or program activities of the adherence club to improve retention in care or improve patients’ adherence to antiretroviral therapy |

| Context | Context refers to salient conditions that are likely to enable or constrain the activation of program mechanisms. | Components of both the physical and the social environment that favor or disfavor the expected outcomes |

| Actors | These are the individuals, groups, and institutions who play a role in the implementation and outcomes of an intervention | This was coded as the actions or actual practices of an individual, group, or institution. |

| Mechanisms | This refers to any underlying determinants or social behaviors generated in certain contexts | Any explanation or justification why a service or a resource was used by an actor to achieve an expected outcome, or considered as a constraint |

| Outcomes | ||

| Immediate outcome | Describes the immediate effect of the adherence club program activities | Immediate outcome typically refers to changes in knowledge, skills, or awareness, as these types of changes typically precede changes in behaviors or practices. |

| Intermediate outcome | Intermediate outcomes refer to behavioral changes that follow the immediate knowledge and awareness changes. | Codes here define a move from direct outcomes to intermediate outcomes, identified through the indirect impact of the activity and accountability of the program. |

| Long-term outcome | Refer to change in the medium- and long-term, such as a patient’s health status, and impact on community and health system | The codes here represent the further indirect impact of the activity demonstrating the lesser accountability of the program. |

While quantitative data and analysis allowed us to identify, classify, and describe the adherence and retention in care behavior of the patients using the adherence club intervention, the nonparticipant observations and realist interviews allowed us to identify intervention modalities, mechanisms, and context factors that interact with the mechanism to perpetuate the observed behaviors.

Results

Qualitative Findings

The qualitative data are reported following the initial program theories (hypotheses).

Mechanisms

Mechanisms related to Initial Program 1

This initial theory relates to how clinically stable patients receiving care in the adherence club program perceive, interpret, and act on the resources and opportunities offered by the club intervention. The postulated mechanisms include perceived stigma, frustration (related to disrupted group dynamics), perceived (lack of) social support from group members, perceived (lack of) support from care providers, encouragement (discouragement), lack of learning opportunities (perceived inadequacy), perceived benefit, and confusion.

Perceived stigma

Because of sharing the same treatment space with other CDL patients, the study participants suggested that the attendance of club activities presented an opportunity for the ART patients of being identified by someone from their community, who is not HIV-positive. This could lead to them being stigmatized in the community.

Sometimes you come for your club date for pick-up; there are social issues with HIV, which we cannot even run away from like stigma. (Counsellor)

The [club] patients also were complaining about them [patients with other chronic conditions] coming inside the place where they [club patients] are being stigmatized. They say they are being stigmatized because outside the building, there were other people, their neighbors, their families and whoever, so it was difficult for them to talk even when the room door was closed. (Nurse)

But you are outside [not in a club room], you are scared to mention your problem because everyone is listening. . . The people will be like, what is going on there? Who are those people? (Patient)

Frustration (related to disrupted group dynamics)

The adherence club teams adopted a model of splitting the adherence club groups into those who were employed and unemployed and merging them with similar groups in another adherence club to form a new “club.” Thereby space issues could be resolved, and potential inadvertent status disclosure to other non-HIV positive patients averted. Those who were employed were given the morning timeslots and those unemployed the 11 o’clock timeslot. Breaking up the groups led to frustration, as one of the participants commented,

The patients are coming a long way with each other. When they come, they share their experiences with each other. Sometimes the patients start the discussions because they are used to one another. So now when we split them, then that one feels, “No! I do not want to be separated from my club. I want my club.” (Nurse)

Perceived (lack of) social support from group members

Patient interaction is identified as a pivotal element of the adherence club intervention. With lack of conducive space to conduct the club activities as dictated by the current conditions of “integration,” patients do not get the time or space to interact with each other as they could when they had a designated conducive space in 2014. This has reduced the social support that patients used to get from each other. Some participants commented on this:

This one can be shy, this one would say I have a pimple there, then its starts from there, you saying things, which are real and then the other one would say! I also have this thing; I did not know it is caused by HIV. (Nurse)

A patient who had experienced the adherence club program when patients could gather as a group and at its current state where there is no conducive meeting area identified the important role of group sharing and social support and the consequences of the absence of “gathering as a club.”

Especially for me, what was very important is when you have a problem; you will be thinking that problem is just affecting you. However, once you come to the club, you can hear many of the people also have the same problem. You will be sharing that problem. At the end of the day, you have a good point on how to solve the problem. That is why I liked the club… Now, we do not have time to share problems together as a club. It already affects us, which if we can be together like before; we can share our problems. … Sometimes you can see someone who has a problem you once had, but because we do not have time to chat together, it is difficult just to approach them. (Patient)

Perceived (lack of) support from care providers

In this theme, we identify from the data instances pointing to supportive health care providers and instances where the health care providers could not provide the support that patients needed because of the circumstances dictating the execution of the adherence club intervention. Regarding perceived support, the health care providers cited an instance where they had to go out of their way to preserve the medication of patients who communicate with them to ensure that the medication is not sent back to the clinic after the five-day grace period.

They arrange with us if someone will not be able to make it. Today, I have four patients who have told me on WhatsApp or called that they will not make it today. They are going to come by that day so I have to take the medication [for safe keep] before it goes to the pharmacy. (Counsellor)

Respondents also recounted instances where social support to patients was not possible due to the prevailing circumstances.

We do not have time to share our problems. If you try to ask a nurse, “I have got this problem, this and this” they will say, “No, you can see all those people, they need my help now. I do not have time to help you” and which is true. (Patient)

The patients have their own things that they want to ask, maybe to the nurse. …but when you come here, everybody [non-HIV-positive patients] is standing here, you cannot even ask what you wanted. (Nurse)

Encouragement (discouragement)

When the adherence club used to work smoothly, and the patients had time to consult with the club facilitators and other health care providers, a patient recounted that they used to get encouragement from the health care providers.

Even the sisters they will encourage you about food, this and that, all those things they talk when you came to club. (Patient)

With some important aspects of the adherence club intervention not being effectuated because of the implementation conditions, another patient stated that she is now discouraged from attending the club sessions (knowing that she can always come and pick up her medication when she wants).

If I want to squeeze and come on my date, I can do it. But because there is no more club [sitting as a group], that means I have no reason to attend. (Patient)

Perceived benefit

The benefit of the adherence club intervention regarding the patient relates to the quick collection/pick-up of their medication packages. In fact, this is the only aspect of the adherence club intervention that is functional and accommodates the absence of a clubroom and the presence of patients with CDL. Two patients recounted how this aspect of the adherence club is beneficial to them.

Yes, I like it [the adherence club] because you can come and get your medication in time, then you can eventually go to work. When you are not in the club, you have to stay for the whole in the queue, maybe you will go home past four o’clock. (Patient)

It is easier for me. Like, I am working, my boss does not give us enough time to come and when we come, we must sit all day. Then he will complain why we sit so long, so it is easier when I just come [to] pick up [my medication] and go. (Patient)

Confusion

One of the club patients recounted how confused they got when they were trying to locate where the adherence club session was taking place because of the displacements that they experienced related to the service integration.

You go to your normal place, room 14 there is no one there, and the door is locked. You wait and look out for the other people. Then, there is this system of integration where people will collect their folders and take their folders to the big weighing room for the normal patient. There, they are being tossed up and down, and not even asked. If our blood pressures could be tested in the morning, you will see that it will be high. There is no direction, there is no movement, and people are standing there not knowing what to do. (Patient)

Initial Program Theory 2

The second initial program theory of the adherence club intervention relates to the role of the rules and regulations of the adherence clubs in driving the behaviors of the patients using the club intervention to enhance and sustain retention of patients in care and their adherence to medication. Themes identified from the data are poor understanding/knowledge of the club rules, perception (or absence) of being punished, and negligence (laxity).

Poor understanding/knowledge of club rules—perceived inadequacy

Following the adherence to club rules and regulations—attending every club session and maintaining good medication adherence—is an important step that guarantees that a patient stays in the adherence club to benefit from its rewards. Some of the health care providers indicated that not having a conducive environment to deliver the club activities deprived them of the chance to make newly recruited club patients understand the club rules and the consequences of not following the club rules and regulations.

Like a new club is starting today. We need to do everything with that patient on that first day, telling the patient about adherence, informing them of the processes, the club rules, and all those stuff. You need to tell the patients those things. Then, where is space? What we do [is that] we just register the patient, and it is not nice to work like that. (Counsellor)

Another counselor suggested that because the patients do not understand or know the club rules, it is difficult for them to follow the club rules.

Yes, patients are not following the club rules anymore. . . because now, that patient will come as a new patient, the patient just knows that she must get a packet [medication] here. She does not know that she has a five-day grace period, she does not know all those stuff, and so [if she does not follow the rules] we send her back to the clinic. Now she is back from clinic care; changing clubs. (Counsellor)

Perceived absence of a feeling of being punished

The second initial program theory of the adherence club suggests that when patients perceive they are being punished by removing them from the adherence club intervention to clinic care—characterized by long waiting times—they tend to adhere to their medication and attend club appointments. The following quotes from the participants suggest that the leniency showed by the health care providers to put patients out of the club when they fail to adhere to the club rules and regulations takes away the perceived fear associated with returning to the main clinic care scheme, thus reducing the effectiveness of the adherence club intervention.

Are you taking your medication or not? To assess the patient for adherence, you need to ask this question to the patients. Then you can see deep down, this one [patient] is not taking the tablets. This one was cheating. This one was changing times and all those things, and then if the viral load keeps on going up, although the patient is on the second line, then you do a pill count. You take the treatment and give the patient weekly supplies. The patient must come back to you after the week’s supply. The patient will take the medication. When you repeat the viral load, it will be low because it is tiring to come to the clinic [frequently], and the patient does not have anywhere to hide. . . (Counsellor)

After one month, they come the following month. We send them now to the floor, go get your folder. From the folder, you go via preparation room. From the preparation, you go to the doctor or to the sister [nurse]. . .whoever sees you there, then no punishment for that patient. Is only that one-day punishment for visiting wrongly, the patient will come back and will be given another two months’ supply of medication and same club visit date. That patient is still now in the club, so you do not know when you book the patient out or when you do not. That is why we say they [clinicians] do not follow a proper structure of the club because it was precisely said, “After five days if the patient does not come, book the patient out.” So now, the patient takes one month, two months and comes back, and on their return, they remain [are kept] in the club. (Counsellor)

Negligence (laxity)

Negligence follows from the lack of knowledge of the club rules and the lack of enforcement of the rules on the part of the health care provider. These conditions instill laxity in the patients, as they do not perceive any threat of being returned from the adherence club to the standard clinic ART care. This is what a participant had to say:

You can see even me; my date was on Thursday the 7th September 2017. However, because there is nothing to rush for, I am only coming today [Tuesday, 19 September 2017]. (Patient)

During our observation, we saw and interviewed patients who failed to attend their routine club appointment, coming weeks later. They were simply asked to go to the pharmacy to check if their medication package was still there. If not, they were sent to see a clinician, who prescribed a month’s supply and then told to attend their next club appointment.

Context

In realist evaluation, “context” relates to the circumstances in which the program is implemented and it is considered as the features of the organization, staffing, history, and so on that are necessary for the program to “fire” the mechanism or that prevent the intended mechanisms from firing. Contextual conditions were identified to influence (an inhibiting role) the implementation and execution of the adherence club intervention. These were the integration of HIV treatment with other CDL, the unconducive environment, the lack of resources, poor adherence club program coordination, experimenting various execution models, and presence of non-HIV-positive patients.

Integration of HIV treatment with other CDL

Previously, the adherence club program had a designated building at the back of the main clinic building. From 2015, there was a pilot of the “service integration” project, whereby ART patients and those with other CDL were managed in an “integrated” fashion—at the same unit. One of the participants described the nature of the service integration:

That is now the aim and the purpose [of the service integration] to mix the club. However, we are not mixed yet, but we are all gathering in this one waiting area. So those people [the other health-care providers] are busy with the chronic [CDL] people that side and we are busy with the HIV people this side. (Counsellor)

The “integration” of these services, nevertheless, seems to impact, especially in a negative manner on the implementation of the adherence club program. This is what a participant said regarding the effects of the service integration:

When we were there [in the facility], we were still separated from the other people [those with CDL], because we are using the same waiting room near the two rooms [Each used by HIV patients and the other by CDL patients]. A normal person could see why these people are sitting in their own space. So, it is already telling somebody, something is wrong with these people. (Counsellor)

We also observed how the patients when they arrived at the unit sat together, but there were minimal interaction and conversation taking place.

Unconducive environment

Reports from the participants indicated that previously, the adherence club program operated in a separate building, with designated spaces to operate two club sessions concurrently. Nevertheless, with the introduction of the notion of “integration,” the area is shared with services pertaining to other CDL making it less convenient for the execution of club activities.

The way the clubs used to run when we were inside this building before [separate designated building for adherence club activities], we could do all sorts of things with the patients. . . especially health education, HIV and AIDs education. We could run the clubs very smoothly on a daily basis, also having one-on-one talks with the patients. It was all about HIV. We could talk about it all the time. Then we were moved inside the building… By going inside the facility, the challenge[s] that we had was, we only got a small room to work in. (Nurse)

Following the service integration, aspects of the adherence club program became disorganized making the environment within which the activities of the club were held unconducive to the health care providers and the patients. This could be identified from the experiences of the following participants:

When we started this thing [integration], we thought HIV would be at the back because the room is there, and then, people with other chronic conditions would be from that black bunk up there. But on the first day, we were shocked, because those people [CDL services] occupied the entire space. We did not know where to go, so we called the [facility] manager. “Can you see what happening?” Because what they said was, it must be back-to-back. This one [group] must face this side and those [the other group] must face that side. It might happen that we [ART services] are quick, and that side [CDL services] is slow and the patients with CDL are asking. What is happening that side? (Adherence club). (Doctor)

Every time we are in the room, we need to close the door and then, there is not enough ventilation and the room was packed because it was just one small room. So, we have been working like that for quite a long time. Until we were sent out again to return to the same building and there we found another challenge where we only got this small room for our activities. (Counsellor)

Lack of resources

Some of the health care providers working on the adherence club cited the lack of resources as challenges they face in the delivery of adherence club services.

You see, so we have been doing that [running the clubs] all along, but we do not have the proper space, proper things to run the place you know! (Nurse)

We came to find out that there are no clubrooms available, only this room and this waiting area here are available for us. We cannot do much in this waiting area because. . . we are together with other chronic illness people here inside. (Counsellor)

Our observation confirmed there was only a small room, which measures about 3 meters in length by 2 meters in width that was allocated for conducting the adherence club activities.

Poor (adherence club) program coordination

Reports from the adherence club implementers indicate challenges regarding the coordination and execution of the adherence club activities, conditions that could influence the uptake of the intervention by the patients. They mentioned irregularities and confusion during the scripting of the patients for medication and in deciding when a patient should be sent out of club care as some of the issues facing the delivery of the club intervention:

So, when it is scripting time, she [Nurse] will do the scripting for all the clubs. Then we have the challenge whereby the clinicians inside, they would send the patient to book for a club, but then the nurse has already scripted for the club patients. (Counsellor)

When the patient has high blood pressure and diabetes, the clinician will ask the patient to go back to the clinic [back-to-regular clinic care]. The next two months or a month later, the patient will come for another check-up, then, if their blood pressure is normal—stable, they will be sent back to the club—another club, but you [the counsellor] have already taken that patient from the club. This renders the [club] registers dirty [untidy]. (Nurse)

Experimenting various execution models

Another contextual condition influencing the execution of the adherence is the experimentation of different implementation models of the adherence club intervention. These changes were related to the frequent changes in the environment and the timeslots. While the changes in the environment were related to the introduction of the “integrated” care model, the changes in the timeslots were an attempt to resolve the issues of space and potential stigma from the non-HIV-positive patients. A participant outlined these changes:

Then we also tried the structure whereby, we select those unemployed ones and the one ones who are employed we give them one slot and the others but still it did not work. People they were used to coming at eight o’clock and then, we eventually, we found people were not coming even at that eleven [o’clock] nor in the afternoon. So, the structures were not working for the timeslots. You see, so we left the timeslots and came back to eight o’clock because no one wants to come at eleven o’clock at the hospital either. (Counsellor)

Presence of non-HIV-positive patients

The presence of non-HIV-infected patients close to where the adherence club patients were receiving care affected the outcomes of the adherence club intervention. With the two services taking place concurrently, there is not enough space to accommodate both services while ensuring patient confidentiality. The size of the adherence clubroom being small means that 25 to 30 patients cannot all fit inside for the club activities to be properly conducted. This means that some aspects of the adherence club, such as health talks, counseling, and instructing the club rules, which can compromise the confidentiality of the club patients are omitted, and only the medication packages of the patients were distributed.

That side [CDL services] is usually slower and the patients there are asking why. “We want to go to that door. It is faster there.” How do you tell them what is in that door? [Adherence club office]. (Counsellor)

At some point, the adherence club team attempted to change the adherence club times to later in the morning so that the patients could come when those with CDL had finished their session, but the health care providers reported that this strategy did not work. This is what they had to say:

We cannot do those stuff anymore [health talks, counselling and club rule instructions] because if we do, we are disclosing the status of our patients. They [clinic management] have been trying to tell us to change our timeslots. We told them that we cannot change the timeslots because these people are working people, they have jobs, they have careers, they go to school so they are just interested to come and get their meds, stay for that hour and go. They are only prepared to stay that hour because we used to tell them that the club is from eight to nine. We tried it [changing the timeslots] for the first and second months. We asked the patients to come on their usual two month’s basis, but it still did not work. (Nurse)

Outcome

The term “outcome” includes short-, medium-, and long-term, intended and unintended changes resulting from the implementation of the adherence club intervention. For the patients using the adherence club, this change could be sustained retention in care and adherence behavior and a change in the experiences of the patients in the program. Outcomes identified from the qualitative data analysis include inadvertent status disclosure, poor club attendance, poor retention in care, and poor adherence to medication.

Inadvertent status disclosure

Some of the study participants suggested that the proximity of non-HIV-positive patients to where HIV-treatment and care services are taking place could lead to inadvertent disclosure of their HIV status, which could lead to perceived stigma. The words of this participant capture this:

Nobody knows that I am HIV positive except my husband. If other people see me outside and we are chatting about HIV and AIDS, they will really know I am HIV positive. Once I walk outside, they will start gossiping about me. “She is HIV positive”. (Patient)

Poor club attendance

Because of the prevailing conditions under which the adherence clubs are being delivered, and the absence of some of its key components of the intervention, patients have been prompted not to honor their club appointments. This was confirmed by a nurse and a patient.

You remember I said there is a five-day grace, now we get patients who stay longer than that five days. After one month, they come the following month. (Nurse)

You can see even me, my date was on Thursday, I was supposed to come on the 7th, on Thursday but because [now there is] nothing to rush for, because all along we were rushing for the club, you see? So now, I just give myself any time that I can just come for my medication. (Patient)

Poor retention in care

According to some health care providers, the repercussion of the integration of services for patients with CDL along with those on ART can be seen in the poor retention in care of those receiving care in the adherence clubs. This is what a club facilitator had to say:

We saw a drop in the [Club] attendance. People did not come, some came later [after club hours] if they came. One or two will come even not at that eleven o’clock slot that we gave them, so we did not actually know what we are doing. (Counsellor)

Poor adherence to medication

Health care providers working on the adherence club also suggested that the poor execution of the adherence club intervention owing to the “integration” of other services into the program affects the medication adherence behavior of patients in the adherence club.

When you do not have health talks, people will take advantage. How? When they come in here, you just give them their treatment then you go, you do not know whether they are taking [their medication] or not because there is no space where you can monitor. Unless after one year, we monitor them, annually. Yes, and then, you could see this patient was not taking treatment for. . . some time. (Nurse)

Quantitative findings

The two main outcomes of interest of the adherence club intervention regarding patient care are retention in care and adherence to medication. Although the adherence club intervention is suggested to produce/give rise to health systems benefits such as reducing the workload of the health care workers and decongesting the local health care facilities (Mukumbang et al., 2016b); these outcomes, at this time, could not be explored in the current study.

Retention in care

An overall retention in care rate of 81.7% was achieved by the two selected adherence clubs within 36 months. The retention in care rates of the various Clubs A and B are represented in Table 4. Although Clubs A and B have different numbers of patients in each club, the retention in care rates of both clubs are comparable (Club A: 80.8% vs. Club B: 82.7%).

Table 4.

Retention in Care Distributions in Two Adherence Clubs at Facility Z.

| Adherence Club | Total Number | Number of Patients Who Dropped Out of the Club | Patients Retained |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | |||

| Club A | 26 | 5 | 21 | 80.8 |

| Club B | 34 | 6 | 28 | 82.7 |

| Combined | 60 | 11 | 49 | 81.7 |

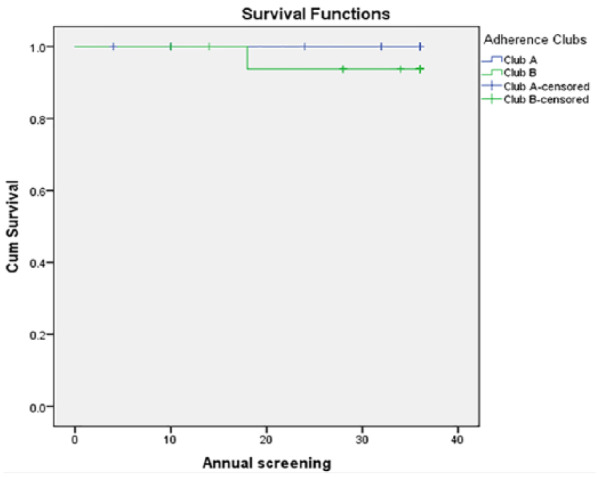

Figure 2a shows the rate at which patients dropped out of the sampled adherence clubs. The survival curve suggests that in the first two years, in Club A 87.8% (confidence interval [CI] = [67.9%, 96.6%]) and in Club B 97% (CI = [83%, 98.8%]) patients were retained in care. However, within the third year, there was a steep drop in the number of patients retained in the two clubs. Based on the hazard function graph (Figure 2b), by the end of the third year, the probability of a patient dropping out of club care is 23% for Club A and 20% for Club B. The log-rank test with a p value of .764 (significance at p < .05) suggests a high level of consistency in the capacity of these two clubs to retain patients in care, as illustrated in the Hazards graph (Figure 2b). An extrapolation of the graph suggests there is an increased possibility that more patients will be dropping out of the adherence club care at the current state of the intervention implementation.

Figure 2.

Survival distribution and hazard function of patient retention in care in two adherence clubs at facility Z.

Adherence to medication

Adherence to medication was measured using the viral load of the patients as a proxy. The adherence to medication was measured as time to viral rebound (viral load > 400 copies/mL). Based on the case studies selected, a total adherence rate of 96.7% was recorded at the end of 36 months in care. A breakdown of the performance of each of these clubs is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Adherence Behavior Distributions in Two Adherence Clubs at Facility Z.

| Adherence Club | Total Number | Number of Patients’ Viral Rebound (VL > 40 Copies/mL) | Patients With Suppressed Viral Load | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | |||

| Club A | 26 | 0 | 26 | 100.0 |

| Club B | 34 | 2 | 32 | 94.1 |

| Combined | 60 | 2 | 58 | 96.7 |

The values in Table 5 suggest very good adherence rates registered by both clubs. Nevertheless, this should be understood in the context that most of the patients who did not show the propensity to maintain good medication adherence have dropped out of club care. The Kaplan–Meier curve (Figure 3) shows how many of the patients had been censored before the end of the study period. When a person dropped out of care for one reason or another, these patients were considered as censored, so we do not know if the event occurred or not (viral rebound).

Figure 3.

Adherence to medication survival curve Two Adherence Clubs at Facility Z.

Data Synthesis

Realist evaluation submits that theories of how, why, for whom, and under what circumstances programs’ work could be formulated by conceptualizing the relational links between the context within which programs are implemented, the generative mechanisms the programs trigger, and the outcomes of interest. After we distilled the various aspects of the implementation of the adherence club intervention at Facility Z according to the elements of the ICAMO heuristic tool, our next task was to conceptualize the links between the different elements. This will help us to compare and contrast the theory obtained to the initial program theory toward confirming, refuting, and modifying the initial program theory (Manzano, 2016).

In testing the initial program theory of the intervention as directed by the data attributed to the intervention, context, actor, mechanism, and outcome collected from the implementation site, the realists work at a level of abstraction where we consider the main mechanisms generating the main patterns of outcomes, a process referred as retroductive inferencing. First, we identified mechanisms and the different outcomes that these mechanisms are likely to perpetuate. Second, we examined the context conditions that were associated with the mechanisms identified as informed by the data.

Our data synthesis followed two steps. First, we constructed an ICAMO matrix table (Table 6). The construction of the ICAMO matrix table followed the process of retroduction—a form of inference that seeks to identify and verify mechanisms that are theorized to have generated the phenomena (Eastwood, Jalaludin, & Kemp, 2014). In our retroductive inferencing, we applied the “configurational” approach to causality, a logic in which outcomes are considered to follow from the alignment, within a case, of a specific combination of attributes (Pawson & Tilley, 2004).

Table 6.

An ICAMO Matrix to Identify and Align the Elements of the ICAMO Heuristic Tool.

| Intervention Modalities | Context | Actor | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Club rules and regulation | • Integration of HIV treatment with other chronic diseases

of lifestyle • Unconducive environment • Lack of resources • Presence of non-HIV positive patients |

• Patient | • Perceived stigma • Poor knowledge of club rules and regulations • Perceived absence of punitive measures |

• Inadvertent disclosure of HIV status • Poor club attendance |

| Group dynamics | • Unconducive environment • Lack of resources • Experimenting various execution models |

• Patient • Group |

• Perceived lack of social support • The feeling of frustration related to loss of group dynamics |

• Reduced adherence related to constant changes and disruptions in group dynamics |

| Health talks/education | • Lack of resources • Presence of non-HIV positive patients • Unconducive environment |

• Patient | • Perceived inadequacy | • Reduced self-efficacy leading to poor retention in care

and medication adherence • Inadvertent disclosure of HIV status |

| Quick medication access | • Unconducive environment • Lack of resources • Experimenting various execution models |

• Patient | • Perceived benefit • Perceived stigma |

• Adherence to medication related to medication

availability • Poor adherence resulting from poor club attendance |

| Prompt continuity of care | • Poor adherence club program coordination and execution | • Clinicians • Patient |

• Role confusion • Dissatisfaction |

• Reduced rate of retention in care |

| Club facilitator–patient relationship | • Unconducive environment • Lack of health talks and counseling sessions |

• Facilitator • Patient |

• Trust • Perceived lack of support |

• Poor adherence to medication • Poor retention in care |

| Overall intervention | • Unconducive environment • Lack of resources • Experimenting various execution models • Presence of non-HIV positive patients • Experimenting various execution models • Poor adherence club program coordination |

• Patients • Club teams |

• Demotivation • Frustration • Confusion |

• Reduced attendance at club sessions • Poor retention in care • Reduced medication adherence rates |

Note. ICAMO = intervention-context-actor-mechanism-outcome.

After obtaining conjectured ICAMO configurations, the second step of the data synthesis was the construction of the configuration map (Figure 4). Following the matrix table, we applied counterfactual thinking (testing possible alternative explanations) to argue toward transfactual (mechanism-centered) conditions (Eastwood et al., 2014). We applied the retroduction logic to configure the elements of the realist heuristic tool (configurational mapping)—assuming the outcomes to follow from the alignment of mechanisms fired in particular contexts—to construct the program theory. By counterfactual thinking, after formulating the possible ICAMO links, we examined each possible alternative configuration for its explanatory power (explanation).

Figure 4.

Configuration map representing the refined program theory.

Finally, using the “if. . ., then. . ., because . . .” statement (Westhorp, 2014), we constructed a program theory of the adherence club intervention based on the data obtained in the case study (Box 2).

Box 2.

Modified Program Theory of the Adherence Club Based on the Case Study Data.

| Grouping clinically stable patients [Actors] receiving quick uninterrupted supply of antiretroviral medication with limited health talks and counseling, inadequate understanding of the club rules and regulations [Intervention] within the context of limited resources (non-conducive clubroom) and integrated care with other patients managed for non-infectious diseases of lifestyle and poorly coordinated club execution [Context], then patients are likely to not attend club sessions and adhere to their medication [Outcome] because they become negligent, frustrated, and demotivated [Mechanisms]. |

Discussion

The objective of this case study was to test the initial program theory of the adherence club intervention in a real-life implementation condition to ultimately refute, concur, or modify the initial program theory. The move from the initial program theory to obtain a causal theory (theory of what happens in practice) is derived by studying various aspects of the program in an implementation scenario. The data obtained from this facility, while it does not exactly match the hypothesized theory, provided very important aspects of the implementation of the adherence club intervention to modify the initial program theory.

The adherence club intervention comprises of four service modalities: quick medication collection, targeted health education and counseling (group-based and individual-based), social environment for sharing, and fast-tracked clinician visits. These treatment modalities are knit together by club rules and regulations. The findings in this study revealed that owing to the circumstances under which the adherence intervention is implemented at Facility Z, only the quick medication collection aspect and fast-tracked clinician visits are effectively implemented. Even the rules that are meant to govern operating the clubs are not adequately applied, and the patients are not fully briefed about the terms and conditions of the adherence club intervention.

In a study conducted by Root and Whiteside (2013) to evaluate what works in another differentiated care program, they identified that the health talk provided to patients and the relationship between the health care providers and the users were most important to the patients. The authors explained that the health talk enhanced treatment uptake and literacy and the real-time interactions between the patients and care supporters were central to the intervention. Our study findings revealed that absence of a conducive space (structure) where patients could be assembled, hindering the delivery of health talks, which took away the aspects of real-time interactions between the patients themselves (group identity) and with the health care providers (adherence support).

Root and Whiteside (2013) suggested that the “relationship” also provided a conducive psychological environment in which patients received support and encouragement when they experienced stigma, medication side effects, and other obstacles to adherence. The effects of the absence of real-time interactions led to the loss of group dynamics, which engendered the feelings of frustration, dissatisfaction, and perceived lack of social support among the patients.

Our study revealed that a disorganized service provision potentially leads to poor uptake of the intervention by the patients. This finding is supported by a study conducted to explore the experiences of patients attending adherence clubs at a primary health care center. In this study, Dudhia and Kagee (2015) uncovered that the logistics around operating the club (delivery of care and support for club team) could place a burden on clinic functioning, thus impacting on the quality of care delivered to patients. The context of disorganized care provision related to lack of resources and support for the club team triggers mechanisms such as dissatisfaction and demotivation, which could influence that retention in care and adherence behaviors of patients.

While exploring the potential for a care model—medication adherence club (MACs) to enhance the management of large numbers of stable patients with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and HIV—Khabala et al. (2015) established the feasibility of MACs for mixed chronic disease managemment in resource-limited settings. Nevertheless, another study conducted to assess patient and health care worker perceptions and experiences of MACs indicated that there were some concerns about the stigmatization of HIV positive patients in groups with non-HIV patients (Venables et al., 2016). Our study also identified that managing patients with different chronic conditions under the same treatment scheme introduces the potential for the HIV positive patients to feel stigmatized by the non-HIV positive patients. Dudhia and Kagee (2015) confirmed that patients felt stigmatized when seen using the adherence club intervention by other patients at the clinic. Stigma has been consistently associated with poor medication adherence and retention in care (Lyimo et al., 2014). Thus, perceived stigma remains an important mechanism (barrier) mitigating the proper functioning of the adherence club intervention in the context of “integrated” care.

According to Pawson and Sridharan (2009), realist hypotheses attempt to differentiate program actors and their circumstances (referred as “contexts”) regarding how they might respond to the adherence club program mechanism. The “integrated” care model, adopted by Facility Z, presents a unique context for the patients using the adherence club intervention regarding the program mechanisms introduced by the intervention. Based on the data, the “integration” presents a different prevailing context within which the adherence club intervention is implemented, characterized by the unconducive environment, lack of resources (adherence club meeting room), the presence of non-HIV-positive patients, different execution models, and poor adherence club program coordination. While the context is supposed to provide the “ideal” conditions to bring the mechanisms into action (Pawson & Tilley, 1997), these mentioned conditions seemed to undermine those mechanisms provided by the adherence club intervention.

Limitations, Rigor, and Trustworthiness

Regarding the retention in care and adherence behaviors of patients in the adherence club, it would have been ideal to obtain the overall rates of the facility. This posed a challenge because the facility is actively creating more clubs monthly, which would potentially affect the overall retention in care and adherence rates of patients in the adherence club program.

To this end, we decided to select, purposively, two adherence clubs that had reached their maximum capacity and to study the rate at which patients drop out of the club for various reasons—default, transferred out of the clinic, lost to follow-up, or died. Another reason that we purposively selected the clubs is related to the muddled nature of the adherence club registers. This follows the poor execution of the adherence club rules, whereby patients would be returned to another adherence club when they show signs of good adherence after being dropped from the club.

To improve the rigor of the study, we adopted the mixed-method approach. The use of a multi-method approach for data collection was informed by their ability not only to improve abductive inspiration but also to confirm and complement the information required to modifying, refuting, and/or verifying the initial program theory. In addition, we used a variety of participants to promote the triangulation of the information obtained and promote facts verification. Finally, in conducting and reporting the study, we followed the guidelines for reporting realist evaluation studies developed by Wong et al. (2016).

Conclusion

The role of context in defining the outcome of health care interventions has been highlighted by implementation scientists and realist evaluators. The findings of this study revealed the prevailing implementation context of the adherence club intervention as presented by an “integrated” model of managing patients with HIV and people with chronic noncommunicable diseases. These findings highlight potential conditions that can mitigate the adherence club intervention mechanisms toward achieving the intended outcome of the intervention. These conditions served toward developing a refined theory explaining how, why, for whom, and under what health system conditions the adherence club intervention works (or not) (Mukumbang, Marchal, van Belle, & van Wyk, 2018b).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, S1_-_Observation_guide for “Patients Are Not Following the [Adherence] Club Rules Anymore”: A Realist Case Study of the Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence Club, South Africa by Ferdinand C. Mukumbang, Bruno Marchal, Sara Van Belle and Brian van Wyk in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, S2_-_Interview_guide-clinicians for “Patients Are Not Following the [Adherence] Club Rules Anymore”: A Realist Case Study of the Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence Club, South Africa by Ferdinand C. Mukumbang, Bruno Marchal, Sara Van Belle and Brian van Wyk in Qualitative Health Research

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, S3_-_Interview_guide-patients for “Patients Are Not Following the [Adherence] Club Rules Anymore”: A Realist Case Study of the Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence Club, South Africa by Ferdinand C. Mukumbang, Bruno Marchal, Sara Van Belle and Brian van Wyk in Qualitative Health Research

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge acknowledge the contributions of the four reviewers who reviewed the work. Their comments and queries provided valuable insights toward improving the article.

Author Biographies

Ferdinand C. Mukumbang is a postdoctoral fellow at the School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, South Africa. His work is focused on differentiated models of care and community-based interventions for managing people living with HIV. He also has interest in theory-building, and the development of research and evaluation methodology for public health.

Bruno Marchal is a professor and the head of the Health Services Organization unit at the Department of Public Health, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (Belgium) and visiting researcher at the School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town. His current research focuses on stewardship of local health systems, research approaches for complex issues in health (including realist research) and life-long conditions.

Sara Van Belle is a political scientist and anthropologist, with a PhD in public health (LSHTM, 2014) and is a post-doctoral fellow at the Institute of Tropical Medicine. She has a keen interest and expertise in governance, accountability and public sector reform, policy analysis, health systems and sexual and reproductive health, and (social) theory-building, and the development of research and evaluation methodology for public health.

Brian van Wyk is an associate professor at the School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape. He is a behavioral scientist with interests in HIV/AIDS and health systems, with particular emphasis on treatment adherence and adolescents.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa (National Health Scholars Program). This research was also funded by an African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship (ADDRF) award offered by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in partnership with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The work was also partly funded by the Framework 4 Agreement between the Belgian Directorate General for Development Cooperation and the University of the Western Cape (grant number: BBD 0344023272).

Supplementary Material: Supplemental Material for this article is available online at journals.sagepub.com/home/qhr. Please enter the article’s DOI, located at the top right hand corner of this article in the search bar, and click on the file folder icon to view.

ORCID iD: Ferdinand C Mukumbang  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1441-2172

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1441-2172

References

- Astbury B., Leeuw F. L. (2010). Unpacking Black boxes: Mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 31, 363–381. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman C. (2013). MSF again paves the way with ART. South African Medical Journal, 103, 71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J. M., Altman D. G. (1998). Survival probabilities (the Kaplan-Meier method). BMJ, 317(7172), Article 1572. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9836663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byng R., Norman I., Redfern S. (2005). Using realistic evaluation to evaluate a practice-level intervention to improve primary healthcare for patients with long-term mental illness. Evaluation, 11, 69–93. doi: 10.1177/1356389005053198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. (2016). Implementation of the universal test and treat strategy for HIV positive patients and differentiated care for stable patients. Pretoria, South Africa: Author; Retrieved from http://www.mhsc.org.za/news/circular-universal-test-and-treat-strategy-hiv-positive-patients-and-differentiated-care-stable [Google Scholar]

- Dudhia R., Kagee A. (2015). Experiences of participating in an antiretroviral treatment adherence club. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20, 488–494. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.953962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood J. G., Jalaludin B. B., Kemp L. A. (2014). Realist explanatory theory building method for social epidemiology: A protocol for a mixed method multilevel study of neighbourhood context and postnatal depression. SpringerPlus, 3(1), Article 12. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsrud A., Barnabas R. V., Ehrenkranz P., Ford N. (2017). Evidence for scale up: The differentiated care research agenda. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 20(Suppl. 4), 22024. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.5.22024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsrud A., Bygrave H., Doherty M., Ehrenkranz P., Ellman T., Ferris R., . . . Bekker L. G. (2016). Reimagining HIV service delivery: The role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. Journal of the Inter-national AIDS Society, 19(1), 21484. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.21484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsrud A., Sharp J., Kalombo C., Bekker L.-G., Myer L. (2015). Implementation of community-based adherence clubs for stable antiretroviral therapy patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(1), 19984. doi: 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]