Abstract

Background

Multiple studies have implicated a role for CD8+T cell-mediated immune response to autoantigens in vitiligo. However, the antigen-specific T lymphocyte reactivity against the peptide epitopes is diverse among different world populations. This study aimed to identify the risk HLA-A allele in vitiligo and study CD8+ T cell reactivity to 5 autoantigenic peptides in Han Chinese populations, and to analyze the association of CD8+ T cell reactivity with disease characteristics.

Material/Methods

The risk HLA-A allele was analyzed by case-control study. Enzyme linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay was used to compare T cell reactivity to the 5 autoantigenic peptides between vitiligo patients and healthy controls, then we analyzed the association of CD8+ T cell reactivity to 2 positive peptides with disease activity and area of skin lesions.

Results

The results indicated that the most frequent allele in the Han Chinese vitiligo patients was the HLA-A*02: 01 allele with a significantly higher frequency compared to controls (20.20% versus 13.79%, P=6.64×10−5). The most frequently encountered epitopes were 2 gp100 modified peptides, IMDQVPFSV and YLEPGPVTV, whereas a weak T cell reactivity against tyrosinase and Melan-A/MART-1 were evaluated. Moreover, we demonstrated that T cell reactivity against the 2 positive peptides was significantly associated with disease characteristics including disease activity and area of skin lesions.

Conclusions

Our findings showed that the HLA-A*02: 01 allele was the major risk HLA-A allele, and 2 gp100 modified peptides were identified as autoantigens and were found to be closely related to disease characteristics which might play a critical role in Han Chinese vitiligo patients.

MeSH Keywords: Autoantigens, CD8-Positive T-Lymphocytes, gp100 Melanoma Antigen, HLA-A Antigens, Vitiligo

Background

Vitiligo is a chronic depigmenting disorder caused by loss of functioning epidermal melanocytes [1]. The mechanism of melanocyte loss in vitiligo was not yet been precisely established. Various theories have been suggested regarding its initiation, including genetic, immune, and environmental factors [2–4]. Moreover, the autoimmunity theory has been the leading hypothesis for causation and has been supported by the clinical association of vitiligo with several other autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and systemic lupus erythematosus [1].

In vitiligo, cytotoxic T cells infiltrating into the perilesional margin are suspected to be involved in the pathogenesis of the disease [1]. Melanocyte antigen-specific T cells are present in perilesional vitiligo skin, and are proven to be capable of killing melanocytes in vitro [5]. Upon melanocyte antigen-specific stimulation, the perilesional CD8+T cells are activated [5]. Although the association between vitiligo and autoimmune reactions has not been fully explained, many melanocytes-expressing proteins have been identified as autoantigens [1]. Cui et al. showed that 24 out of 29 vitiligo patients (83%) had autoantibodies to melanocytes-associated autoantigen versus 2 out of 28 healthy controls (7%) [6]. So far, various proteins have been detected as autoantigens in vitiligo, including tyrosinase [7–9], tyrosinase-related protein 1 [10,11], tyrosinase-related protein 2 [12,13], Pmel17 (gp100) [14,15], tyrosine hydroxylase [16], lamin A [17], and MART-1 [18]. A number of studies have demonstrated that specific cellular immune response is mainly directed against the melanin synthesis related protein tyrosinase, gp100, and MART-1 [1]. However, T cell reactivity differed against different peptide epitopes, and conflicting results have been found in previous studies for T cell responses to the same epitopes [19–21]. It still remains unclear whether the autoantigens identified in Caucasians play a critical role in Han Chinese populations.

While the strongest genetic associations of vitiligo is the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), the specific associated MHC loci and alleles are diverse among different world populations [22]. In this study, we analyzed the risk HLA-A allele in a case-control study in the Han Chinese populations and compared T cell reactivity to 5 autoantigenic peptides, comparing vitiligo patients and healthy controls. As Mandelcorn-Monson et al. claimed, if the dominant epitopes that mediate vitiligo are identified, it would be possible to design therapies to treat this disease with antagonist peptide ligands that could block specific T cell responses [20]. Therefore, our study will deepen our understanding of autoimmunity in vitiligo etiology and shed new light on the immune therapy for vitiligo patients.

Material and Methods

Study participants

Study participants consisted of 255 vitiligo patients (generalized vitiligo) enlisted from the Department of Dermatology, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University. All materials from patients and healthy controls were collected after obtaining informed consent and approval by the ethics review board of the Fourth Military Medical University. In all, 42 HLA-A*02: 01 positive vitiligo patients and 32 healthy controls were included in the ELISPOT assay. Following informed consent, information of patients’ characteristics, family history, disease activity, and area of the skin lesions were collected mainly by questionnaire. The selected vitiligo patients in this study did not have any systemic treatment (including immunosuppressive therapy or phototherapy) during at least 3 months, as described in our previous research [23].

The disease activity classification of vitiligo was based on case history as described in our previous study [24,25]. Patients without obvious progressive during the last 3 months were classified as stable vitiligo disease, patients with rapidly increase of lesion during the last 3 months were classified as actively progressive. Among the 42 HLA-A*02: 01 positive vitiligo patients, there were 20 cases of stable vitiligo and 22 cases of actively progressive vitiligo. There were no patients with the other autoimmune disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Vitiligo patients (n=42) | Healthy controls (n=32) | |

|---|---|---|

| Range of age in months, mean (SD) | 11–74, 32.9 (15) | 13–67, 32.09 (14.6) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 24 (57) | 20 (62) |

| Female | 18 (43) | 12 (38) |

| Range of disease during in months, Mean (SD) | 1–324, 96.71 (109.83) | NA |

| Disease of activity of vitiligo, n (%) | NA | |

| Stable (no progress in past 3 months) | 20 (47.6) | NA |

| Active (rapidly progress within 3 months) | 22 (52.4) | NA |

| The area of skin lesions, n (%) | NA | |

| <5% | 21 (50) | NA |

| 5–50% | 17 (40.5) | NA |

| >50% | 4 (9.5) | NA |

NA – not applicable; SD – standard deviation.

HLA typing and PBMCs preparation

We drew 1 mL fresh blood samples from vitiligo patients and used the samples to extract Genomic DNA. The specific operation was performed using the Blood Genomic DNA Extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the kit description. We used 1% agarose gel electrophoresis to detect and assure DNA quality. Qualified DNA samples were provided to Songon Biotech Company (Shanghai, China) and HLA genotyping were performed using PCR-SBT.

We collected 25 mL to 30 mL heparinized blood samples and used the samples to isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The isolations of PBMCs were performed by Ficoll gradient centrifugation (Dakewe, Beijing, China) as described in our previous study [23]. Red Blood Cell Lysis Buffer was used to resuspend PBMCs and remove the red blood cells. Hank’s balanced salt solution (Gibco, USA) was used to wash the PBMCs. And then the PBMCs were plated in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) or frozen in cell freezing medium containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma, USA) until needed for further experiments.

Peptide synthesis

The 5 HLA-A2-restricted peptides used in the ELISPOT assays are shown in Table 2: gp100 protein: 209–217.2M (IMDQVPFSV) and 280–288.9V (YLEPGPVTV) [26]; MelanA/MART-1: 26–35.2L (ELAGIGILTV) [27] and 26–35 (EAAGIGILTV) [28,29]; and tyrosinase: 369–377.3D (YMDGTMSQV) [30]; CD3 as a positive control, and HIV Gag: 77–85 (SLYNTVATL) as irrelevant control [31]. All the peptides which were used in the experiment were synthesized and provided by Sangon Biotech Company (Shanghai, China).

Table 2.

Peptides used for the detection of specifically reactive cytotoxic T cells.

| Peptide sequence | Protein | Position | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| YMDGTMSQV | Tyrosinase, 3D (modified) | 369–377 | Human |

| IMDQVPFSV | gp100, 2M (modified) | 209–217 | Human |

| YLEPGPVTV | gp100, 9V (modified) | 280–288 | Human |

| ELAGIGILTV | MART-1, 2L (modified) | 26–35 | Human |

| EAAGIGILTV | MART-1 | 26–35 | Human |

ELISPOT assays

ELISPOT assays were performed as described in our previous study [23]. PBMCs were unfrozen, washed, and incubated overnight in DAYOU medium (Dakewe, Beijing, China) at 37°C in 5% CO2. The IFN-γ ELISPOT plates (ELISpotPRO for human IFN-γ, Mabtech, Stockholm, Sweden) enveloped with IFN-γ were washed 5 times with PBS, and then 2×105 PBMCs were added to the IFN-γ ELISPOT plate. Then the 2 modified gp100 peptides (209–217.2M and 280–288.9V, 10 μg/mL), MelanA/MART-1peptides (26–35, 10 μg/mL), modified MelanA/MART-1peptides (26V35.2L, 10 μg/mL), and modified tyrosinase peptide (369–377.3D, 10 μg/mL) were added to the ELISPOT plate. CD3 (1: 1000) antibody served as positive control, and HIV Gag: 77–85 (SLYNTVATL) as irrelevant control. Plates were developed 48 hours later at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were discarded, and plates were washed 5 times with PBS. Biotinylated anti-IFN-γ antibody (1 μg/mL) was added to the plates to detect captured IFN-γ 100 μL. After incubating for 2 hours at room temperature, the plates were washed 5 times with PBS, followed by addition of phosphatase substrate solution BCIP/NBT-plus. The tap water was used to stop the reaction until distinct spots appeared. The blue spots were counted using an ELISPOT Image Analyzer and software (Cell Technology Inc., Jessup, MD, USA). The spot forming cells (SFC) were defined as described in our previous research [23] as SFC=experimental group–irrelevant control group.

Statistical testing

Chi-squared test was used to compare the allele frequency distributions in vitiligo patients and healthy controls and analyzed using SPSS software (version 19.0). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to analyze the results of the ELISPOT assays using the unpaired t-test, and P<0.05 was considered with statistically significant difference.

Results

The HLA-A*02: 01 was a risk HLA-A allele in Han Chinese vitiligo patients

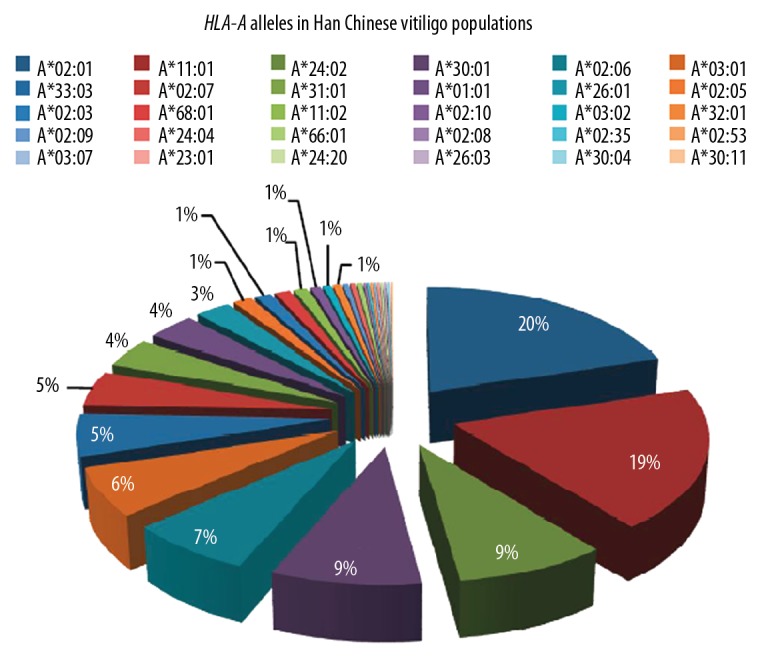

The study consisted of 255 patients with generalized vitiligo and 106 89 healthy controls in Han Chinese populations. The data of 10 689 controls was derived from the study by Zhang X et al. [32]. As shown in Figure 1, the frequency of HLA-A*02: 01 allele accounted for the biggest percentage in these patients, and was 20.20%, followed by HLA-A*11: 01 (19.02%), HLA-A*24: 02 (8.63%), HLA-A*30: 01 (8.63%), HLA-A*02: 06 (7.25%), and HLA-A*03: 01 (6.47%). Moreover, compared with the control group, the proportion of HLA-A*02: 01 (P=6.64×10−5), A*03: 01 (P=7.42×10−5), and A*02: 05 (P=0.001) were significantly increased in vitiligo patients; reversely, HLA-A*24: 02 (P=8.02×10−7), A*33: 03 (P=0.042), and A*02: 07 (P=0.028) were significantly reduced in the vitiligo patients (Table 3).

Figure 1.

HLA-A alleles in Han Chinese vitiligo populations. The HLA-A*02: 01 allele (20.20%) accounted for the most frequency in patients, followed by: HLA-A*11: 01 (19.02%), HLA-A*24: 02 (8.63%), HLA-A*30: 01 (8.63%), HLA-A*02: 06 (7.25%), and HLA-A*03: 01 (6.47%).

Table 3.

HLA-A alleles demonstrated significant differences in vitiligo patients compared with healthy controls from Han Chinese populations.

| HLA-A allele | Vitiligo | Controls | Vitiligo versus healthy controls | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | 1 P-value | ||

| A*02: 01 | 103 (20.20) | 2947 (13.79) | 6.64×10−5 | 1.58 (1.27–1.97) |

| A*11: 01 | 97 (19.02) | 3970 (18.57) | 0.778 | 1.03 (0.82–1.29) |

| A*24: 02 | 44 (8.63) | 3633 (15.73) | 8.02×10−7 | 0.46 (0.34–0.63) |

| A*30: 01 | 44 (8.63) | 1426 (6.67) | 0.084 | 1.32 (0.97–1.81) |

| A*02: 06 | 37 (7.25) | 1213 (5.67) | 0.143 | 1.3 (0.93–1.83) |

| A*03: 01 | 33 (6.47) | 687 (3.21) | 7.42×10−5 | 2.08 (1.45–2.99) |

| A*33: 03 | 28 (5.49) | 1717 (8.03) | 0.042 | 0.67 (0.45–0.98) |

| A*02: 07 | 24 (4.70) | 1568 (7.33) | 0.028 | 0.62 (0.41–0.94) |

| A*31: 01 | 20 (3.92) | 775 (3.63) | 0.731 | 1.09 (0.69–1.71) |

| A*01: 01 | 18 (3.53) | 766 (3.58) | 0.986 | 0.98 (0.61–1.58) |

| A*02: 05 | 7 (3.33) | 56 (0.26) | 0.001 | 5.3 (2.4–11.7) |

| A*26: 01 | 13 (2.54) | 582 (2.72) | 1.000 | 0.94 (0.54–1.63) |

| A*02: 03 | 6 (1.18) | 521 (2.44) | 0.077 | 0.48 (0.21–1.07) |

| A*68: 01 | 6 (1.18) | 172 (0.80) | 0.314 | 1.47 (0.65–3.33) |

| A*11: 02 | 5 (0.98) | 351 (1.64) | 0.29 | 0.59 (0.24–1.44) |

| A*02: 10 | 4 (0.78) | 91 (0.43) | 0.287 | 1.85 (0.68–5.05) |

| A*32: 01 | 3 (0.59) | 322 (1.51) | 0.095 | 0.39 (0.12–1.21) |

| A*03: 02 | 3 (0.59) | 50 (0.23) | 0.126 | 2.52 (0.79–8.12) |

| A*66: 01 | 2 (0.39) | 19 (0.09) | 0.085 | 4.43 (1.03–19.05) |

| A*02: 09 | 2 (0.39) | 14 (0.07) | 0.052 | 6.01 (1.36–26.5) |

| A*24: 04 | 2 (0.39) | 8 (0.04) | 0.022 | 10.52 (2.23–49.65) |

| A*24: 20 | 1 (0.20) | 68 (0.32) | 1.000 | 0.62 (0.09–4.44) |

| A*23: 01 | 1 (0.20) | 50 (0.23) | 1.000 | 0.84 (0.12–6.08) |

| A*11: 03 | 1 (0.20) | 18 (0.08) | 0.361 | 2.33 (0.31–17.5) |

| A*30: 04 | 1 (0.20) | 16 (0.07) | 0.33 | 2.62 (0.35–19.82) |

| A*30: 11 | 1 (0.20) | 6 (0.03) | 0.152 | 7 (0.84–58.23) |

| A*26: 03 | 1 (0.20) | 5 (0.02) | 0.132 | 8.4 (0.98–72.01) |

CI – confidence interval; OR – odds ratio.

P-value was calculated by using Chi-squared test.

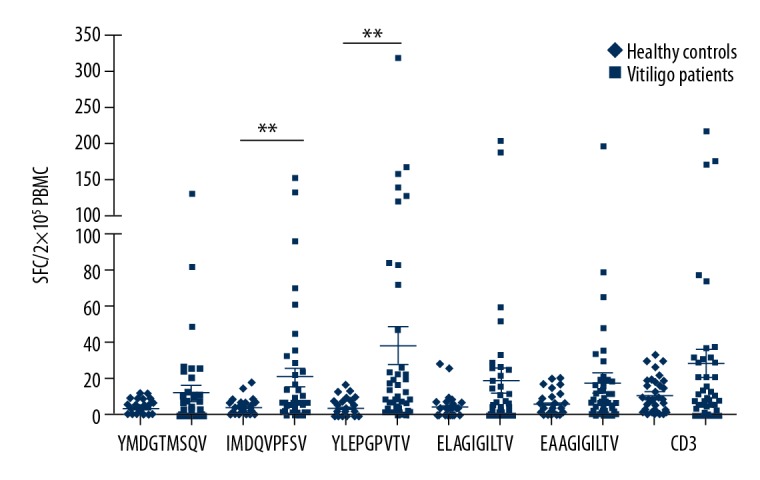

CD8+T lymphocyte reactivity to 2 gp100 modified peptides was evaluated in HLA-A* 0201 vitiligo patients

Previous studies have shown that melanocyte antigens, including the modified gp100 epitopes, tyrosinase, and MART-1 peptides, acted as triggers for immune responses of CD8+ T cells of vitiligo patients [20,21]. Thus, we examined the reactivity of CD8+T cells to 5 epitopes which were derived from gp100/tyrosinase/MART-1 in 42 HLA-A* 02: 01-restricted Han Chinese vitiligo patients.

The results demonstrated that the immunodominant epitopes were 2 gp100 modified peptides: gp100 209-217,2M (IMDQVPFSV) and gp100 280-288,9V (YLEPGPVTV). As shown in Figure 2, PBMCs isolated from vitiligo patients showed significantly stronger reactivity to immunodominant epitopes than the healthy controls (P<0.01). Meanwhile, 6 out of 42 patients showed reactivity to gp100 280–288.9V, with spots more than 100 per 2×105 cells. Furthermore, only 1 patient demonstrated no reactivity against the gp100 280–288.9V (YLEPGPVTV), and 3 out of 42 patients showed no reactivity to gp100 209–217.2M (IMDQVPFSV).

Figure 2.

Ex vivo ELISPOT assays for 5 antigenic peptides in HLA-A*02: 01 vitiligo patients. Patient PBMCs (2×105 per well) were cultured directly on the ELISPOT plate with 5 antigenic peptides (10 μg/mL) respectively, including tyrosinase 369–377.3D (YMDGTMSQV), gpl00 209–217.2M (IMDQVPFSV), gpl00 280–288.9V (YLEPGPVTV), MART-1 26–35.2L (ELAGIGILTV), and MART-l 26–35 (EAAGIGILTV.) Plates were developed 48 hours later and detected by ELISPOT assays. The CD3 antibody was served as positive control, and HIV Gag: 77–85 (SLYNTVATL) as irrelevant control. Each group was set up in triplicate. The significant difference reactivity to the melanocyte antigens demonstrated between vitiligo patients and healthy controls. ** P<0.01. Non-parametric student’s t-test, P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Weak reactivity of peptide specific response to tyrosinase and Melan-A/MART-1

Previous studies demonstrated that the reactivity of antigen-specific CD8+T cells to tyrosinase and MelanA/MART-1 peptides were controversial [20,21]. In this study, 18 out of 42 patients demonstrated reactivity against all the epitopes, including 3 epitopes derived from tyrosinase and MelanA/MART-1. Seven of 42 patients showed no reactivity against both tyrosinase 369–377,3D (YMDGTMSQV) and MelanA/MART-1 26–35.2L (ELAGIGILTV). Besides, 4 out of 42 patients demonstrated no reactivity against EAAGIGILTV (MelanA/MART-1 26–35). Whereas 17 out of 42 patients showed low reactivity to tyrosinase 369–377.3D (YMDGTMSQV) with less than 10 spots per 2×105 cells. In addition, 14 of 42 and 16 of 42 patients demonstrated low reactivity to MelanA/MART-1 26–35.2L (ELAGIGILTV) and MelanA/MART-1 26–35 (EAAGIGILTV) with less than 10 spots per 2×105 cells, respectively (Figure 2). These results indicated that there was a weak reactivity of peptide specific response to tyrosinase and Melan-A/MART-1.

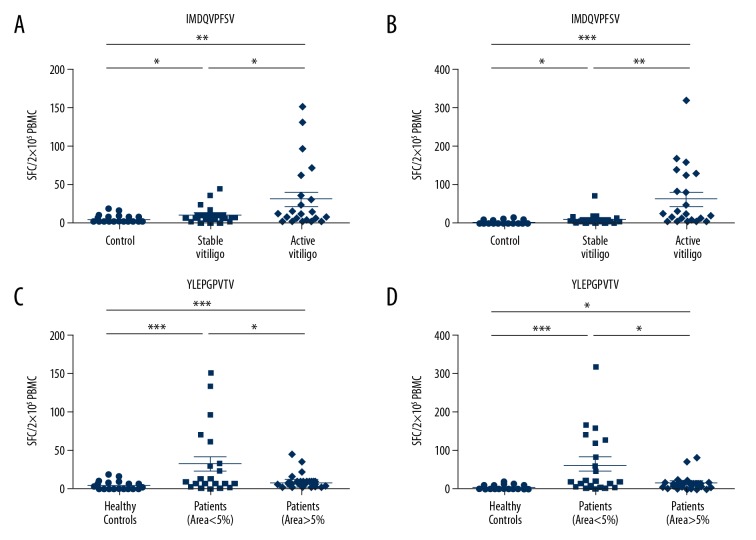

The CD8+ T cell reactivity to 2 modified gp100 peptides was associated with disease characteristics

In order to test whether there was a correlation between disease activity and CD8+ T cell reactivity to 2 modified gp100 peptides, we compared the reactivity of PBMCs between stable and active vitiligo patients. The results demonstrated that there was stronger CD8+ T cell reactivity of active vitiligo patients against gp100 209–217.2M (IMDQVPFSV) and gp100 280–288.9V (YLEPGPVTV) than stable patients (P<0.05 and P<0.01 respectively, Figure 3A, 3B). These results indicated that the CD8+ T cell reactivity to 2 modified gp100 peptides were associated with disease activity. Furthermore, to determine whether the T cell reactivity to 2 modified gp100 peptides was associated with the area of skin lesions, we next compared the PBMCs reactivity between vitiligo patients with the area of skin lesions less than 5% and more than 5%. As shown in Figure 3, compared with more than 5% skin lesions, there was significantly stronger reactivity of vitiligo patients with less than 5% skin lesions against 2 modified gp100 peptides (P<0.05 and P<0.05 respectively). Altogether, the results demonstrated that the CD8+ T cell reactivity to 2 modified gp100 peptides was significantly correlated with the area of skin lesions.

Figure 3.

Association of disease characteristics and CD8+ T cell reactivity to 2 modified gp100 peptides. (A) There were significantly stronger reactivity of active vitiligo patients against the gp100 209–217,2M (IMDQVPFSV) than stable patients (* P<0.05). (B) The significantly stronger reactivity was detected against the gp100 280–288.9V (YLEPGPVTV) in active vitiligo patients than stable patients (**P<0.01). (C) There was significantly stronger CD8+ T cell reactivity against gp100 209–217.2M (IMDQVPFSV) in vitiligo patients with less than 5% skin lesions than vitiligo patients with more than 5% skin lesions (* P<0.05). (D) Vitiligo patients with skin lesions of less than 5% encountered significantly stronger reactivity against the gp100 280–288.9V (YLEPGPVTV) than vitiligo patients with more than 5% skin lesions (* P<0.05). Non-parametric student’s t-test.

Discussion

Previous studies indicated that HLA-A*02 subtype was associated with vitiligo [33]. This HLA-A*02 subtype was widely expressed in 35–45% of the USA population [34]. In this study, 20.20% (103 out of 510) of Han Chinese vitiligo patients were identified as HLA-A*02: 01, which accounted for the highest in all HLA-A subtypes, followed by HLA-A*11: 01 (19.02%), HLA-A*24: 02 (8.63%), HLA-A*30: 01 (8.63%), HLA-A*02: 06 (7.25%), and HLA-A*03: 01 (6.47%). Furthermore, we compared HLA-A allele frequencies between vitiligo patients and healthy controls in the Han Chinese populations and found that the frequencies of A*02: 01 and A*03: 01 were significantly increased in vitiligo patients, suggesting that these subtypes were the risk alleles for vitiligo in the Han Chinese populations. However, the HLA allele frequencies might vary among different ethnic groups. Singh et al. demonstrated that the primary association of HLA with vitiligo in North India and Gujarat was not with A*02: 01, but with A*33: 01, B*44: 03, and DRB1*07: 01 [35]. Jin et al. carried out next-generation DNA sequencing of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C exons 2, 3, and 4, which contained the sequence variations that define HLA subtypes, suggesting that the vitiligo-associated HLA-A region SNPs tagged both HLA-A*02: 01 and HLA-A*02: 06, and also occasional non-HLA-A*02 alleles, but do not tag specific alleles of HLA-B or HLA-C in Japanese populations [22]. Moreover, Jin et al. reported that MHC class I association derived from HLA-A, specifically HLA-A*02: 01, in European-derived white vitiligo patients [3,36]. This indicates that the specific associated MHC loci and alleles are diverse among different world populations.

A lot of studies have supported the concept that the destruction of melanocytes was due to the autoimmune reaction in progressive vitiligo [1]. Moreover, candidate antigens to be targeted by T cells in vitiligo were from melanoma research. Most T cells infiltrating in melanoma could respond to melanocyte differentiation antigens that are also expressed in normal melanocytes, including tyrosinase, gp100, MelanA/MART-1, TRP-2, and TRP-1 [37]. However, different studies have reported conflicting results due to the differences of area distribution of the patients, progression of disease, and HLA-A sites. Inconsistent conclusions were obtained regarding the role of melanocyte-associated autoantigen in vitiligo, especially the tyrosinase and Melan-A/MART-1 [20]. In our study, we evaluated T cell reactivity to 5 autoantigenic peptides from tyrosinase, gp100, and MelanA/MART-1 that have been confirmed in Caucasians in HLA-A2-positive patients with vitiligo. It was indicated that the most frequent immunodominant epitopes were 2 gp100 modified peptides: gp100 209-217,2M (IMDQVPFSV) and gp100 280–288,9V (YLEPGPVTV). This was consistent with a previous study by Rochelle et al., which showed that antigen-specific T lymphocyte reactivity against gp100 peptides 209.2m/280.9v was detected in 15 out of 17 (88%) patients [20]. Our findings in a larger sample size of 36 out of 42 patients (85.7%,) indicated a significant association between CD8+T lymphocyte reactivity against modified gp100 and vitiligo. Parkhurst et al. showed that modification of either the gp100 epitopes 209 to 217 or 280 to 288, via substituting amino acids at the primary anchor residues for peptide/MHC binding, could improve MHC binding affinity and enhance CD8+ T cell specific responses [26].

Gp100, a melanocyte-specific expressing protein, plays a critical role for melanogenesis in melanocytes and melanoma cells [21]. In this study, we found a positive correlation between vitiligo disease activity and reactivity to gp100. There was a significantly stronger T cell reactivity of active vitiligo patients to both gp100 209–217.2M (IMDQVPFSV) (P<0.05) and gp100 280–288.9V (YLEPGPVTV) (P<0.01) than stable patients. This finding supported the viewpoint that a significant association was demonstrated between T cell reactivity against gp100 peptides and disease activity by Lang et al. [21] and Rochelle et al. [20]. We next noted that there was a positive association between the area of skin lesions and T cell reactivity against 2 modified gp100 peptide. This demonstrated that there was a significantly stronger T cell reactivity to modified gp100 peptides in vitiligo patients with less than 5% involved skin area than vitiligo patients with more than 5% involved skin area (P<0.05). To sum up, these results demonstrated the gp100-specific T cells played a pathogenic role in vitiligo, and CD8+ T cell reactivity to gp100 peptides was significantly associated with disease characteristics.

Previous studies demonstrated that the reactivity of antigen-specific CD8+T cells to MelanA/MART-1 and tyrosinase peptides were controversial. Palermo et al. showed plenty of both MelanA/MART-1 and tyrosinase-specific T cells from PBMCs of HLA-A2-positive vitiligo patients were stained using HLA-melanocyte peptide tetramersin in vitro [38]. On the contrary, Rochelle et al. showed that reactivity to both MelanA/MART-1 and tyrosinase peptides might be found at low levels and in a small group of their patients (28%) [20]. In our study, several patients showed low and no reactivity against MelanA/MART-1 and tyrosinase peptides, indicating that that there was weak reactivity of peptide specific response to tyrosinase and Melan-A/MART-1. The controversy between our findings and previous studies may at least partly be explained by different antigen-specific T lymphocyte reactivity to the peptide epitopes among different world populations.

A number of studies indicated that CD8+ T cells specific for melanocyte antigens, including MelanA/MART-1, gp100, and tyrosinase, had been detected in the peripheral blood and perilesional skin of patients with vitiligo [5,20,38]. Although there has been little report about directly using epitope peptides for vitiligo treatment, Mandelcorn-Monson et al. considered that it was possible to treat vitiligo with antagonist peptide ligands that could block specific T cell responses [20]. Besides, in a multiple sclerosis (EAE) mouse model, Casares et al. showed that systemic delivery of nanoparticles coated with autoimmune-disease-relevant peptides bound to MHC II molecules could trigger antigen-specific regulatory CD4+T cell type 1-like cells, further leading to resolution of established autoimmune phenomena [39]. Thus, our study may provide new clues for vitiligo immunotherapy in the future.

Conclusions

Our findings showed that HLA-A*02: 01 allele was the major risk HLA-A allele, and 2 gp100 modified peptides were identified as autoantigens and closely related to disease characteristics which may play a critical role in Han Chinese vitiligo patients. Our study supported that autoantigens mediated T cell immune response to melanocytes played a key role in the pathogenesis of vitiligo.

Footnotes

Source of support: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no.81472863, no.81130032, no.81703096, no.81472893, no.81402599, no.81502717)

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, van Geel N. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):74–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60763-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Poole IC, Das PK, van den Wijngaard RM, et al. Review of the etiopathomechanism of vitiligo: A convergence theory. Exp Dermatol. 1993;2(4):145–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1993.tb00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richmond JM, Frisoli ML, Harris JE. Innate immune mechanisms in vitiligo: danger from within. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(6):676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandoval-Cruz M, Garcia-Carrasco M, Sanchez-Porras R, et al. Immunopathogenesis of vitiligo. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10(12):762–65. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Boorn JG, Konijnenberg D, Dellemijn TA, et al. Autoimmune destruction of skin melanocytes by perilesional T cells from vitiligo patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(9):2220–32. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui J, Arita Y, Bystryn JC. Characterization of vitiligo antigens. Pigment Cell Res. 1995;8(1):53–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1995.tb00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song YH, Connor E, Li Y, et al. The role of tyrosinase in autoimmune vitiligo. Lancet. 1994;344(8929):1049–52. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91709-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baharav E, Merimski O, Shoenfeld Y, et al. Tyrosinase as an autoantigen in patients with vitiligo. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105(1):84–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp EH, Gawkrodger DJ, MacNeil S, et al. Detection of tyrosinase autoantibodies in patients with vitiligo using 35S-labeled recombinant human tyrosinase in a radioimmunoassay. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109(1):69–73. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12276556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemp EH, Waterman EA, Gawkrodger DJ, et al. Autoantibodies to tyrosinase-related protein-1 detected in the sera of vitiligo patients using a quantitative radiobinding assay. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):798–805. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jimbow K, Chen H, Park JS, et al. Increased sensitivity of melanocytes to oxidative stress and abnormal expression of tyrosinase-related protein in vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(1):55–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.03952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemp EH, Waterman EA, Gawkrodger DJ, et al. Identification of epitopes on tyrosinase which are recognized by autoantibodies from patients with vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113(2):267–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemp EH, Gawkrodger DJ, Watson PF, et al. Immunoprecipitation of melanogenic enzyme autoantigens with vitiligo sera: evidence for cross-reactive autoantibodies to tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related protein-2 (TRP-2) Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109(3):495–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4781381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemp EH, Gawkrodger DJ, Watson PF, et al. Autoantibodies to human melanocyte-specific protein pmel17 in the sera of vitiligo patients: A sensitive and quantitative radioimmunoassay (RIA) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114(3):333–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemp EH, Waterman EA, Gawkrodger DJ, et al. Molecular mapping of epitopes on melanocyte-specific protein Pmel17 which are recognized by autoantibodies in patients with vitiligo. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;124(3):509–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kemp EH, Emhemad S, Akhtar S, et al. Autoantibodies against tyrosine hydroxylase in patients with non-segmental (generalised) vitiligo. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20(1):35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Lv Y, Li C, et al. Vitiligo autoantigen VIT75 is identified as lamin A in vitiligo by serological proteome analysis based on mass spectrometry. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(3):727–34. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teulings HE, Willemsen KJ, Glykofridis I, et al. The antibody response against MART-1 differs in patients with melanoma-associated leucoderma and vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27(6):1086–96. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams S, Lowes MA, O’Neill DW, et al. Lack of functionally active Melan-A(26–35)-specific T cells in the blood of HLA-A2+ vitiligo patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(8):1977–80. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandelcorn-Monson RL, Shear NH, Yau E, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte reactivity to gp100, MelanA/MART-1, and tyrosinase, in HLA-A2-positive vitiligo patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121(3):550–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris JE. Cellular stress and innate inflammation in organ-specific autoimmunity: Lessons learned from vitiligo. Immunol Rev. 2016;269(1):11–25. doi: 10.1111/imr.12369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin Y, Hayashi M, Fain PR, et al. Major association of vitiligo with HLA-A*02: 01 in Japanese. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28(3):360–62. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui T, Yi X, Guo S, et al. Identification of novel HLA-A*0201-restricted CTL epitopes in chinese vitiligo patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep36360. 36360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Yi X, Jian Z, et al. A single-nucleotide polymorphism of miR-196a-2 and vitiligo: an association study and functional analysis in a Han Chinese population. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2013;26(3):338–47. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song P, Li K, Liu L, et al. Genetic polymorphism of the Nrf2 promoter region is associated with vitiligo risk in Han Chinese populations. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20(10):1840–50. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkhurst MR, Salgaller ML, Southwood S, et al. Improved induction of melanoma-reactive CTL with peptides from the melanoma antigen gp100 modified at HLA-A*0201-binding residues. J Immunol. 1996;157(6):2539–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valmori D, Fonteneau JF, Lizana CM, et al. Enhanced generation of specific tumor-reactive CTL in vitro by selected Melan-A/MART-1 immunodominant peptide analogues. J Immunol. 1998;160(4):1750–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Jennings C, et al. Recognition of multiple epitopes in the human melanoma antigen gp100 by tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor regression. J Immunol. 1995;154(8):3961–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romero P, Gervois N, Schneider J, et al. Cytolytic T lymphocyte recognition of the immunodominant HLA-A*0201-restricted Melan-A/MART-1 antigenic peptide in melanoma. J Immunol. 1997;159(5):2366–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skipper JC, Hendrickson RC, Gulden PH, et al. An HLA-A2-restricted tyrosinase antigen on melanoma cells results from posttranslational modification and suggests a novel pathway for processing of membrane proteins. J Exp Med. 1996;183(2):527–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Hull LK, et al. Sequence motifs important for peptide binding to the human MHC class I molecule, HLA-A2. J Immunol. 1992;149(11):3580–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou F, Cao H, Zuo X, et al. Deep sequencing of the MHC region in the Chinese population contributes to studies of complex disease. Nat Genet. 2016;48(7):740–46. doi: 10.1038/ng.3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu JB, Li M, Chen H, et al. Association of vitiligo with HLA-A2: A meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(2):205–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis JM, Henson V, Slack R, et al. Frequencies of HLA-A2 alleles in five U.S. population groups. Predominance Of A*02011 and identification of HLA-A*0231. Hum Immunol. 2000;61(3):334–40. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(99)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh A, Sharma P, Kar HK, et al. HLA alleles and amino-acid signatures of the peptide-binding pockets of HLA molecules in vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(1):124–34. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laddha NC, Dwivedi M, Mansuri MS, et al. Vitiligo: Interplay between oxidative stress and immune system. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22(4):245–50. doi: 10.1111/exd.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Poole IC, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, van den Wijngaard RM, et al. Autoimmune aspects of depigmentation in vitiligo. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9(1):68–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palermo B, Campanelli R, Garbelli S, et al. Specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against Melan-A/MART1, tyrosinase and gp100 in vitiligo by the use of major histocompatibility complex/peptide tetramers: The role of cellular immunity in the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(2):326–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clemente-Casares X, Blanco J, Ambalavanan P, et al. Expanding antigen-specific regulatory networks to treat autoimmunity. Nature. 2016;530(7591):434–40. doi: 10.1038/nature16962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]