Case Report

A 11-year-old girl who attained menarche 1 year back was evaluated for hematuria of 1 month duration. Ultrasound showed a mass lesion in the bladder. Cystoscopy revealed a 6.4 × 4 cm lesion arising from the right lateral and anterior wall of the bladder. Biopsy from the tumor was suggestive of primitive neuroendocrine tumor. Histopathology revealed a neoplasm composed of cells arranged in alveolar pattern cells having scanty cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei in a background of eosinophilic material suggestive of malignant small round cell neoplasm. Immunohistochemistry was done with synaptophysin, which was positive in occasional cells and CD99 antigen (Cluster of differentiation 99), also known as MIC2 which showed strong membrane staining suggesting PNET. Since there was no disparity between the morphology and the IHC, EWS FLI 1 was not done.

Imaging was done by MRI pelvis, which showed an intravesical mass of 7 × 6.3 × 5 cm arising from the anteroinferior wall of the bladder on the right side with extravesical extension and breach of serosa. A bone marrow biopsy was done, which showed myeloid and erythroid adequate in a ratio of 1:1 with normal maturation and adequate megakaryocytes. CT scan of thorax was negative for metastasis. The case was discussed in the pediatric multidisciplinary board and decision was made for induction chemotherapy followed by surgery. She received 6 cycles of induction chemotherapy with vincristine, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide, alternating with ifosphamide and etoposide. Post-chemo, her MRI showed residual lesion 3 × 4.5 cm with minimal bladder wall infiltration. She was planned for partial cystectomy and postoperative radiation therapy. The option of fertility preservation was discussed with her parents, and it was decided to do Ovarian transposition (OT) during surgery. She was taken up for surgery after informed consent. Intraoperative cystoscopy was done and lesion identified by transillumination. Growth was seen in the anterior wall of bladder, 3 cm from the right vesicourethral junction. A wide excision of the lesion was done, the bladder was closed in two layers, and a suprapubic catheter was placed. Bilateral ovaries were detached from the uterus and transposed to the paracolic gutters after dissecting the ovarian vessels.

Postop period was uneventful and she was discharged uneventfully. She did not have any voiding difficulties. Histopathology of resected specimen came as a primitive neuroectodermal tumor bladder, tumor size of 3 × 3 × 3 cm and margins clear. Following surgery, she received pelvic radiation 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions. At present, she has completed her treatment and is on follow-up with a disease-free status. She has attained her menstrual cycles twice after treatment completion.

Discussion

PNET is a rare malignancy and there is very little literature on PNET arising from urinary bladder. It comes under the spectrum of “Ewing sarcoma family of tumors” (EFT). Ewing sarcoma usually affects bones. It can less commonly be seen in the soft tissue called extraosseous Ewing sarcoma. The term PNET was coined by Arthur Purdy Stout, who in 1918 described a small round cell neoplasm in the ulnar nerve. Later, James Ewing described a tumor of undifferentiated cells in the long bones, which was named as Ewing’s sarcoma after him. It was observed over the years that these two tumors share the same translocation and represent a similar spectrum of disease and are members of EFTs.

PNET is classified into central nervous system (CNS) PNET and peripheral PNET. Peripheral PNET is much less common. Being rare, it is difficult to diagnose this malignancy. Other differential diagnosis of round cell neoplasms include small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, and small cell variant of malignant melanoma [1]. Differentiation from them is by combined histological, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analysis of the cells. Histology shows tumor composed of small, round, blue cells with a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio. The nuclei stain dark and form a cord-like or sheet-like arrangement. The small round cells may form a pseudorosette formation or the Homer Wright rosettes. They exhibit specific chromosomal translocations on 22q12, 11q24, which is seen in 90% of cases. Antibodies to CD99 are used in diagnostic immunohistochemistry to distinguish Ewing’s sarcoma from other tumors of similar histological appearance. Distinct membranous staining is seen for Ewing/PNET and cytoplasmic staining for other tumors [2–4].

EFT have similar clinical features, including a peak incidence between 10 and 20 years, a tendency to metastasize to lungs, bone and bone marrow, and responsiveness to the same chemotherapeutic regimens and radiation therapy. Some patients may be seen to have subclinical metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Such patients are also seen to have high relapse rates with local therapy alone (80 to 90%) [5–7]. The presenting symptoms of patients with bladder PNET include hematuria, polyuria, anuria, dysuria, and lower abdomen mass and pain abdomen. They are more commonly identified in young adults and adolescents, and are known to be relatively aggressive. Because of the rarity of the neoplasm, there are no definite guidelines regarding its management. PNET is managed by a multimodality approach with surgery or radiation for local disease, which is preceded by induction chemotherapy [8, 9].

Local treatment of PNET should be radiation or surgery or a combination of both. There are no randomized trials comparing these two modalities and considering the rarity of this disease; treatment decisions are individualized. Surgery has been shown to be the best for local control of disease. In situations when the disease is unresectable or when it may not be possible to preserve an organ, these patients are ideal candidates for radiation preceded by induction chemotherapy [7, 10]. In this patient, considering the initial tumor bulk and extra serosal spread of the tumor, it was decided to treat her with induction chemotherapy followed by surgery and pelvic radiation. Radiation can also be considered in the settings when the resected margins are close or positive.

Our patient presented with gross hematuria, and following induction chemotherapy, there was decrease in size of the mass, and she was taken up for partial cystectomy along with an OT as she was planned for local radiotherapy postoperatively. OT is an accepted technique in patients with pelvic malignancies planned for pelvic radiation. Other options of fertility preservation include embryo cryopreservation and ovarian tissue cryopreservation.

OT is surgical relocation of ovaries preserving its blood supply to a site outside the radiation field. It is done in young patients prior to pelvic radiation with the intention of preserving ovarian function. By transposing the ovaries away from the pelvis, the reproductive as well as hormonal function of ovaries are retained. So, the quality of life of these survivors of childhood cancers should also be taken into account in their treatment plan. The long-term effect of OT in preservation of ovarian function has been studied in the past [11–14]. The extent of damage by RT depends on the dose of RT used, age at exposure, and drugs used for chemotherapy. A single dose of 2 Gy was shown to decrease the ovarian reserve by > 50% [15, 16]. OT can be done either by laparotomy, laparoscopy, or robotic approaches. It is a relatively simple procedure involving the detachment of ovary from the uterus and fallopian tube and making an incision in the peritoneum below the ovarian vessels in the infundibulopelvic ligament to mobilize it, so that it can be fixed to the proposed site like the paracolic gutters. Another approach was proposed as a modification in laparoscopy approach. Here, a prolene suture on a straight needle is passed through a small incision on the abdomen where OT is planned, and it can be fixed to anterior abdominal wall by subcutaneous sutures [17]. On completion of treatment, the sutures are removed to release the ovaries back to pelvis. OT has been shown to decrease the radiation exposure to ovaries by 50–90%. In a study of 122 patients who underwent OT, 50% had early menopause [18]. There is limited data as such on OT in PNET, and much of it is for other malignancies as described above. There are several studies showing variable success rates for OT. In a study in 1992, 12 pregnancies were reported in 18 children who underwent OT at a mean age of 9.4 years [11]. In another study after a follow-up of 14 years in Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 14 pregnancies were reported in 11 women, of which 11 delivered successfully. There was no increased risk for abortion, congenital abnormality, and prematurity as compared to general population [19]. P Morice et al. reported on 37 women with different malignancies, including vaginal clear cell adenocarcinomas, ovarian dysgerminomas, and pelvic soft tissue sarcoma. They reported an overall pregnancy rate of 15% in vaginal adenocarcinoma and 80% in ovarian dysgerminoma and sarcoma. The cases of vaginal adenocarcinoma were those with history of DES exposure causing morphological abnormality in their genital tracts, and hence the lower fertility rate [20].

The concept of fertility preservation is upcoming in oncology practice. With newer and better treatment modalities improving the cure rate of cancers, the long-term issues of cancer survivors are very relevant. Permanent infertility is one of the most important issues affecting the quality of life of cancer survivors. OT aims at preserving hormonal function of the ovary and possibility of pregnancy once she is cured of cancer. This option should be offered to all patients planned for pelvic radiation as ovarian tissue is very much susceptible to radiation. Efficacy of OT has been reported by many studies, including a meta-analysis, which had 1189 patients with ovarian function retained in 70% [21].

This case report emphasizes on the radical treatment of this rare malignancy and offering fertility preservation to those planned for pelvic radiation. Figs 1, 2 and 3.

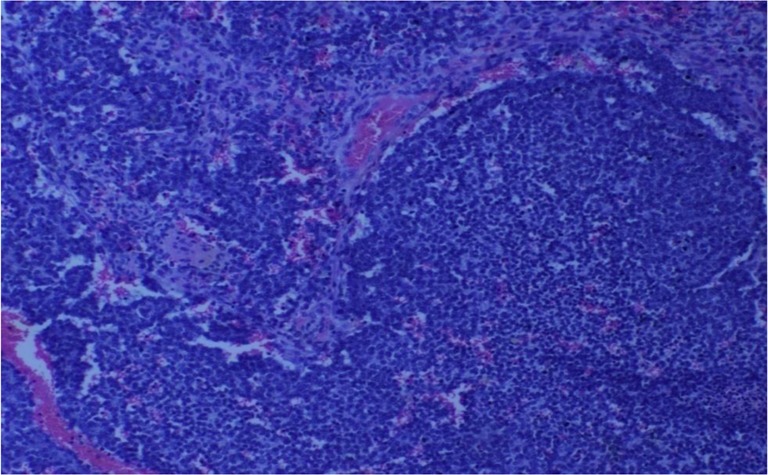

Fig. 1.

H&E (× 200) section showing malignant round cells with a rossetoid pattern with intervening vascular channels

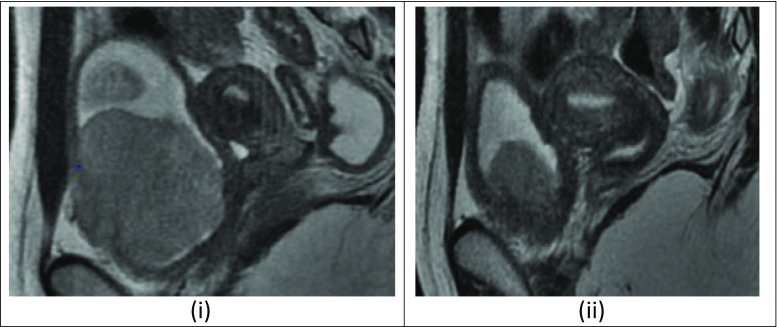

Fig. 2.

(i) Pre chemo MRI showing 7 × 6.3 × 5 cm bladder mass arising from the anteroinferior wall of bladder on right side: (ii):Post-chemo MRI showing residual lesion 3 × 4.5 cm with minimal bladder wall infiltration

Fig. 3.

(i): Mass lesion arising from anterior wall of bladder. (ii): Resected specimen. (iii): Left ovary (white arrow) and fallopian tube (black arrow) transposed to the paracolic gutter

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Reshmi John, Email: reshjohn83@gmail.com.

Arun Peter Mathew, Email: arunpeter@gmail.com.

References

- 1.De Alava E, Pardo J. Ewing tumor: tumor biology and clinical applications. Int J SurgPathol. 2001;9:7–17. doi: 10.1177/106689690100900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez Beltran A, Perez Seoane C, Montironi R, Hernandez-Iglesias T, Mackintosh C, de Alava E. Primary primitive neuroectodermaltumor of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathological study emphasising immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and molecular analyses. J ClinPathol. 2006;59:775–778. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.029199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee SS, Eyden BP, RJ MV, Bryden AA, Clarke NW. Primary peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the urinary bladder. Histopathology. 1997;30:486–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishii N, Hiraga H, Sawamura Y, Shinohe Y, Nagashima K. Alternative EWSFLI1 fusion gene and MIC2 expression in peripheral and central primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Neuropathology. 2001;21:40–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2001.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar V, Khurana N, Rathi AK, Malhotra A, Sharma K, Abhishek A, et al. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of prostate. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008;51:386–388. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.42518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher CD. Peripheral neuroectodermal tumors. In: Franz ME, Weiss SW, editors. Soft Tissue Tumors. 3. St. Louis: Mosby Co; 1995. pp. 1221–1250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.FriedrichsN VR, Poremba C, Schafer KL, Böcking A, Buettner R, et al. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) in the differential diagnosis of malignant kidney tumors. Pathol Res Pract. 2002;198:563–569. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkitaraman R, George MK, Ramanan SG, Sagar TG. A single institution experience of combined modality management of extra skeletal Ewings sarcoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikitakis NG, Salama AR, O’Malley BW, Jr, Ord RA, Papadimitriou JC. Malignant peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor-peripheral neuroepithelioma of the head and neck: a clinicopathologic study of five cases and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2003;25:488–498. doi: 10.1002/hed.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruger S, Schmidt H, Kausch I, Bohle A, Holzhausen HJ, Johannisson R, Feller AC. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) of the urinary bladder. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:751–754. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thibaud E, Ramirez M, Brauner R, Flamant F, Zucker JM, Fékété C, Rappaport R. Preservation of ovarian function by ovarian transposition performed before pelvic irradiation during childhood. J Pediatr. 1992;121(6):880–884. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Detti L, Martin DC, Williams LJ. Applicability of adult techniques for ovarian preservation to childhood cancer patients. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29(9):985–995. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9821-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrenz B, Henes M, Neunhoeffer E, Fehm T, Lang P, Schwarze CP. Fertility preservation in girls and adolescents before chemotherapy and radiation - review of the literature. Klin Padiatr. 2011;223(3):126–130. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green DM, Sklar CA, Boice JD, Jr, Mulvihill JJ, Whitton JA, Stovall M, Yasui Y. Ovarian failure and reproductive outcomes after childhood cancer treatment: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2374–2381. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leiper AD, Stanhope R, Lau T, Grant B, Blacklock H, Chessells JM, Plowman PN. The effect of total body irradiation and bone marrow transplantation during childhood and adolescence on growth and endocrine function. Br J Haematol. 1987;67(4):419–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace WH, Thomson AB, Kelsey TW. The radiosensitivity of the human oocyte. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):117–121. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gareer W, Gad Z, Gareer H. Needle oophoropexy: a new simple technique for ovarian transposition prior to pelvic irradiation. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(7):2241–2246. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1541-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feeney DD, Moore DH, Look KY, Stehman FB, Sutton GP. The fate of the ovaries after radical hysterectomy and ovarian transposition. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56(1):3–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terenziani M, Piva L, Meazza C, Gandola L, Cefalo G, Merola M. Oophoropexy: a relevant role in preservation of ovarian function after pelvic irradiation. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(3):935.e15–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morice P, Thiam Ba R, Castaigne D, Haie-Meder C, Gerbaulet A, Pautier P, Duvillard P, Michel G. Fertility results after ovarian transposition for pelvic malignancies treated by external irradiation or brachytherapy. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(3):660–663. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mossa B, Schimberni M, Di Benedetto L, Mossa S. Ovarian transposition in young women and fertility sparing. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(18):3418–3425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]