Abstract

Background

Further research gaps exist in relation to the promotion of breastfeeding. Robust scientific evidence obtained by a meta-analysis would provide objectively summarized data while enabling the assessment of consistency of findings. This review includes the first documented meta-analysis done on the effectiveness of targeting fathers for promoting breastfeeding (BF). Assessments have been done for a primary outcome and for six more secondary outcomes.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, Google Scholar, CENTRAL databases and unpublished researches were searched. Selections of randomized-controlled trials and quasi-experimental studies were done in three rounds. Heterogeneity and potential publication bias were assessed. Eight studies were included in meta-analysis and others in narrative synthesis of the outcomes. Pooling was done with the Mental- Haenszel method using risk ratio (RR). Summary-of-Findings table was composed by Review-Manager (version 5.3) and GRADEproGDT applications. Subsequent sensitivity analysis was done.

Results

Selected eight interventional studies included 1852 families. Exclusive BF at six months was significantly higher (RR = 2.04, CI = 1.58–2.65) in the intervention groups. The RR at 4 months was 1.52 (CI = 1.14 to 2.03). Risk of full-formula-feeding (RR = 0.69, CI = 0.52–0.93) and the occurrence of lactation-related problems were lower in the intervention groups (RR = 0.24, CI = 0.10–0.57). More likelihood of rendering support in BF-related issues was seen in intervention groups (RR = 1.43, CI = 1.22–1.68). Increase of maternal knowledge and favorable attitudes on BF were higher in the intervention groups (P ≤; 0.001). The quality of evidence according to GRADE was “low” (for one outcome), “moderate” (for four outcomes), and “high” (for two outcomes).

Conclusions

Targeting fathers in promotion of BF has provided favorable results for all seven outcomes with satisfactory quality of evidence.

This review was registered in the PROSPERO-registry (ID: 2017-CRD42017076163) prior to its commencement.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Fathers’ influence on breastfeeding, Exclusive breastfeeding, Breastfeeding promotion, Infant nutrition, Partner support in breastfeeding

Background

Breast milk is regarded as the best source of nutrition a newborn can get [1]. It provides favorable outcomes to the baby as well as to the mother [2–6]. These outcomes are not only limited to growth-related, immunological, and economic benefits, but also extend to a larger scope with the assumption of influencing genetic-dynamics as well [7]. Furthermore, breastfeeding has been found to be associated with favorable adult outcomes like prevention of chronic non-communicable diseases which are becoming global epidemics [8–11]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommend an exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) period of 6 months for all settings [1, 12–14]. Since 2001, this recommended duration has not been changed until now [15, 16]. Yet in many communities, the breastfeeding norms are being challenged [17, 18]. It has been mentioned that in certain settings of low and middle-income countries, the cumulative prevalence of EBF in babies younger than 6 months is less than 40% [6]. In many of high-income countries, the duration of EBF period is shorter compared to resource-poor settings [6].

There are certain factors that increase as well as decrease the duration of EBF. Lack of family and social support have been determined as detrimental factors associated with the exclusivity and duration of breastfeeding [1, 19]. In addition, the occurrence of lactation-related problems like breast engorgement, sore nipples, incorrect attachment, and promotion of formula feeding have been recognized as negatively influencing factors of breastfeeding [20, 21]. In contrast, higher knowledge of mothers on breastfeeding helps to promote it [20].

Promotion of breastfeeding needs multilevel supportive measures with interventions being implemented through several channels [17]. Fathers have been named as one recommended target in promoting breastfeeding [22, 23]. Qualitative research findings have revealed some domains of the father’s role in breastfeeding [24]. Yet, literature suggests that “fathers or male partners” have not been given adequate emphasis in the promotion of breastfeeding [18, 25].

The available research findings of observational studies point towards a positive correlation between the support of the male partner and the likelihood of continuation of breastfeeding [18, 25, 26]. Even the perceived support of the partner is linked with favorable levels of self-efficacy [27]. In addition to their support, the attitudes of the husband have been documented as determinants of breast feeding self-efficacy [28, 29]. In contrast, some literature does not recommend the “broad application of male involvement” in promoting EBF [30]. A cohort study has documented that though their emotional support does, the practical support of fathers as not being associated with better breastfeeding [31]. Similarly, a study done in India has revealed that though the fathers’ attitudes support breast feeding, they do not influence the duration of EBF [32].

Child nutrition programs require much more investments and commitments globally [13]. At the same time, more scientific literature is needed in determining the effectiveness of interventions on breastfeeding as there are issues on the generalizability of currently available evidence [33]. The WHO has highlighted that more scientific evidences are needed “across different regions, countries, population groups and contexts, in order to adequately and sensitively protect, promote and support breastfeeding.” [34]. Meta-analysis of systematically reviewed data would provide objectively-summarized precise data and enable assessing the consistency of findings [35]. It is recommended that the use of randomized control studies as an ideal strategy in determining the effectiveness of interventions which target breastfeeding [36, 37]. When randomization is not possible, quasi-experimental studies may produce better evidence than observational studies in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions [38, 39].

The present review included assessing a primary outcome as well as six secondary outcomes. First, a specific objective was to conduct a meta-analysis on its effectiveness on the adherence to EBF practices at the end of 6 months as the primary outcome. The second specific objective included six other secondary outcomes which are complementary parameters in determining the effectiveness of breastfeeding or factors which significantly influence the primary outcome. They were: EBF at the end of 4 months, full formula-feeding within 2 months, support of the father, prevalence of breastfeeding related problems, knowledge of the mother on breastfeeding, and the attitudes of the mother on breastfeeding.

Methods

Protocol and registration

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were referred [40]. The review was registered in the PROSPERO-International prospective register of systematic reviews registration (2017-CRD42017076163). Subsequent amendments were made in the protocol clarifying the eligibility criteria further.

Eligibility criteria

The research question was composed based on PICOS and SPIDER sequence [41]. It was formulated as “targeting the father/male-partner in addition, more effective than targeting the pregnant or new mother alone, in promoting breastfeeding with evidences of interventional studies.”

The criteria for the selection of studies included: being a randomized or quasi experimental study, the intervention group including the male partners, and the intervention being delivered either in the antenatal period and/or within the postnatal period.

Search strategy

The PubMed, EMBASE, Google Scholar and CENTRAL-Cochrane library were searched. Our search strategy was ‘breastfeeding’ AND ‘expectant father OR father OR male partner.’ By contacting the fellow colleagues of the related fields, attempts were made to seek any unpublished literature. Furthermore reference lists of the selected articles and references of the systematic reviews were carefully studied in tracing the eligible articles.

Selection of studies

The selection of the studies was done in three rounds. In the first round, original research articles, which were compatible with the general objective of the present review, were selected. In the second round, articles on experimental studies were retained. In the third round, the studies which are compatible with the specific objectives were retained. In the first and second rounds, when the selection could not be done by the details mentioned in the abstracts, full articles were referred. Full articles were compulsorily referred in the third round.

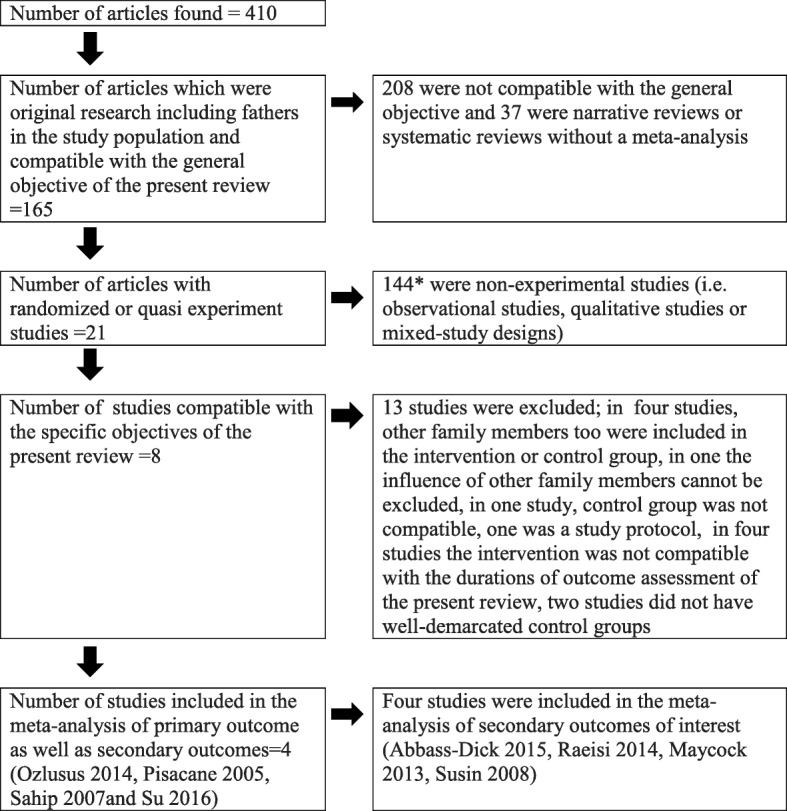

The selection of articles was done by two independent reviewers. It was ensured that in selected articles, the intervention had been specifically targeting breastfeeding promotion. The articles which were selected by both reviewers were identified first. When there was a disparity, a third reviewer was involved to resolve it following a discussion with original reviewers. Following de-duplication, 410 articles were selected to be screened (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow-diagram on the selection of studies

Data-extraction

Data extraction was done by two reviewers independently using a pre-designed template. A third reviewer ensured the similarity of the two datasets of the initial reviewers. The extracted variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Extracted variables from selected studies

| Population | Intervention | Comparison | Outcome | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -Eligibility criteria -Characteristics of the participants |

-Kind of intervention/s done with duration/s | -Number of arms -Number participated -Number completed the allocated exposure |

-Primary and secondary outcomes -How the outcomes were measured -Number of participants with each outcome |

-Type of design -Year of conduct -Study setting |

Estimation of bias

The risk of bias table was composed based on the recommendations for the randomized trials and quasi experimental studies [42–47]. The bias assessment was based on the methodological issues related to random number generation, allocation concealment, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and any other bias. Determination of the level of bias was done by two reviewers independently and was contributed by a third reviewer in case of a disparity of decisions. Publication bias was assessed by a funnel plot [48].

Meta-analysis and narrative synthesis

The assessment for statistical heterogeneity of the selected studies was done with chi-square and I-square tests for all the meta-analyses [48, 49]. The cut-off of the I-square test for heterogeneity was considered as 50% and for the p value of chi-square test was considered as 0.1 [42, 48]. Meta-analysis was done by the software Review Manager (version 5.3) having done the heterogeneity assessments [50]. Mental- Haenszel method was used in pooling. Fixed-model assumptions were used in meta-analysis which was complemented by the random-model assumptions in assessing the robustness of findings. Risk Ratio (RR) was used as the effect measure as it has been described as less-misleading compared to the Odds Ratio [51, 52]. Narrative synthesis was done when the selected studies were found be heterogeneous by both chi-square statistic and I-square values [53, 54]. Combined results were presented in a Summary of Findings (SoF) table (Table 2) [55]. The quality of evidence was assessed with the criteria of “Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) Working Group” with the help of the “GRADEproGDT” application [45–47].

Table 2.

Summary of Findings (SoF) Table

| Effectiveness of targeting fathers for breast feeding promotion | ||||||

| P - Expectant and new fathers I – Health education on breast feeding C – Educating only the mother O – Promotion of breast feeding | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed riska | Corresponding riskb | Relative effect | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of evidence GRADE | Comments |

| Exclusive BF for six months | 201 per 1000 | 411 per 1000 (318 to 534) | RR = 2.04 (1.58–2.65) | 587 [71–74] (4 studies) | Moderatec | Meta-analysis done |

| EBF for four months | 194 per 1000 | 294 per 1000 (221 to 393) | RR = 1.52 (1.14 to 2.03) | 507 [72, 73, 77] (3 studies) | Lowd | Meta-analysis done |

| Full formula feeding within two months | 247 per1000 | 170 per 1000 (128 to 230) | RR = 0.69 (0.52 to 0.93) | 721 [73, 76] (2 studies) | Moderatee | Meta-analysis done |

| Support of the father | 548 per 1000 | 783 per 1000 (668 to 920) | RR = 1.43f (1.22 to 1.68) | 383 [73, 75, 78] (3 studies) | Highg | Meta-analysis done for two studies [75, 78] and narrative synthesis done for one study [73] |

| In the third study (Su 2016), fathers in the intervention group knew how to support continuation of breast feeding. When a breastfeeding related problem occurred, they provided solid support. The fathers in the control group did not know how to support even if they wanted to. | ||||||

| Knowledge of the mothers on breast feeding (BKS scale and a developed tool) | In one study (Su 2016), mothers’ knowledge on breastfeeding increased by 19.75 points in the experimental group and by 14.81 in the control group (p = 0.009). In another study (Raesi 2014), the pre-study knowledge was not significantly different in the two groups whereas the post-intervention knowledge was 103 in the experimental group and 95.71 in the control group (P < 0.0001). | 169 [73, 75] (2 studies) | Moderateh | Narrative synthesis done | ||

| Breast feeding related problems | 179 per 1000 | 43 per 1000 (18 to 102) | RR = 0.24 (0.10 to 0.57) | 280 [71] (1 study) | Highi | Narrative synthesis done |

| Maternal attitudes towards breast feeding (IIFAS scale) | The increase of maternal attitudes towards breastfeeding was significantly more in the intervention group (p = 0.001) | 69 [73] (1 study) | Moderatej | Narrative synthesis done | ||

aTotal events divided by the total participants in the control group

bFunction of “assumed risk” and the “relative effect”

cQuality was downgraded due to risk of bias (2 points) and upgraded for large effect (1 point)

dQuality was downgraded due to risk of bias (2 points)

eQuality was downgraded due to risk of bias (1 points)

fMeta-analysis was done for findings of two studies as the third was heterogeneous

gQuality was downgraded due to risk of bias (1 points) and upgraded for large effect (1 point)

hQuality was downgraded due to risk of bias (2 points) and upgraded for large effect (1 point)

iQuality was downgraded due to risk of bias (1 points) and upgraded for large effect (1 point)

jQuality was downgraded due to risk of bias (2 points) and upgraded for large effect (1 point)

Assessing the robustness of the results

The sensitivity analysis was done by re-performing the meta-analysis with random-model assumption following the initial fixed-model assumption [56, 57]. Furthermore, it was done by repeating the meta-analysis of the primary outcome leaving out one study at a time [58].

Results

Selection of studies

The selection-related details of the studies are summarized in Fig. 1. Twenty experimental studies were thus selected in the second round. Out of these twenty, thirteen studies were excluded in the third round [20, 59–70]. Out of the remaining eight studies, four were included in the meta-analysis of the primary as well as secondary outcomes of interest [71–74]. Four others were included in meta-analysis of the secondary outcomes [75–78]. All eight studies included 1852 families. During the search, only one article which gives the impression of an experimental study by the title, could not be traced [79].

Interventions of the studies

Interventions consisted of Information-Education-Communication methodologies including; face-to-face discussions, power-point presentations, usage of brochures, usage of models, leaflets, and electronic media. In three studies (Su 2016, Sahip 2007, Raeisi 2014) the intervention was done during the antenatal period [73–75]. In two studies (Ozlusus 2014, Maycock 2013) the intervention started in the antenatal period and extended in to the neonatal period [72, 76]. In three studies (Susin 2008, Pisacane 2005, Abbass-Dick 2015), the intervention was done in the neonatal period [71, 77, 78].

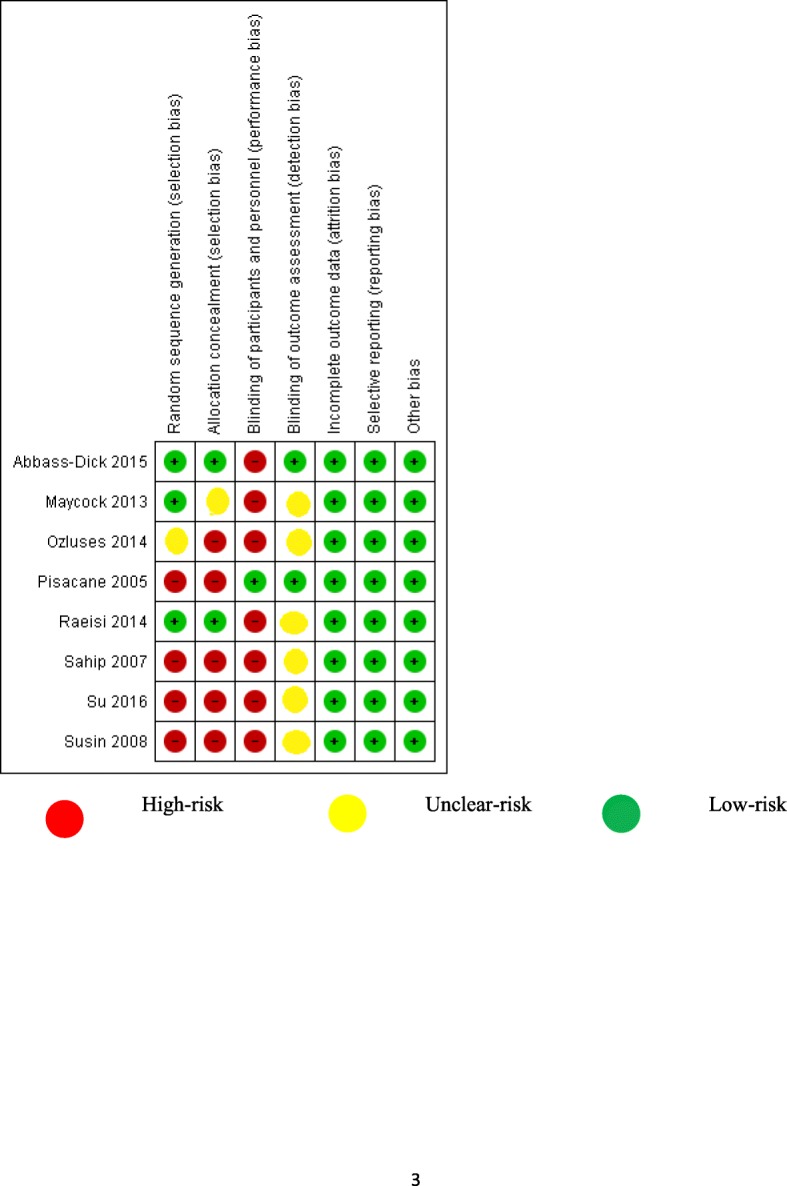

Results of bias assessment

All eight studies were with low risks of attrition, reporting, and other biases. Blinding of participants was done only in the study of Piscane (2015). High-risk of bias due to issues related to random number generation and allocation concealment could not be excluded respectively in four and five studies (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias summary of individual studies

Meta-analysis of the primary outcome

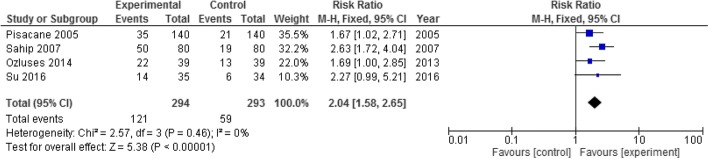

Four studies were selected for the meta-analysis for the first specific objective (i.e. primary outcome) (Table 3). This meta-analysis included 587 families with 294 in the experimental group (i.e. the male partner involved in the health education) and 293 in the control group (male partner not involved in the health education). The four selected studies seemingly were not significantly heterogeneous (I2 = 0%, p value = 0.46). The pooled RR was 2.04 (CI = 1.58 to 2.65). It reflects that compared to a baby whose father has not participated in a breastfeeding promotional intervention, a baby whose father attended such an intervention is more than two times as likely to be exclusively breastfed for 6 months (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the selected studies for the meta-analysis of the primary outcome

| Study | Study | Population | Comparison | Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Ozlusus, 2014 [72] | Turkey, Experimental study | -Ability to read, write and speak Turkish -Who were hoping to live in a mentioned area in Turkey until infants would be six months |

1. Control group (No intervention) with 39 families 2. Experimental group I (Only mothers) with 39 participants 3. Experimental group II (Both mom and dad) with 39 families |

Education manuals, demonstrations. Fathers’ education done during visiting hours (from the day mother got admitted until the day of discharge) | -Exclusive breast feeding: Control- 12.8%, Group I- 33.3%, Group II- 56.4 |

| 2. Pisacane, 2005 [71] | Italy, A controlled trial | Parent-pairs of healthy, term normal birth weight infants. unmarried women, | 1. Intervention group - 280 participants (140 mothers and 140 fathers) 2. Control group B- 280 participants (140 mothers and 140 fathers) |

Intervention included a face-to-face 40 minute session on infant feeding, difficulties in breast feeding including their management. A leaflet given at the end. | -Full Breast feeding at six months: Intervention group-25%, Control- 15% |

| 3. Sahip, 2007 [74] | Turkey Interventional study. | Expectant fathers attending the workplaces in which a trained physician was available consisted the intervention group. | 1.Intervention, 80 2. Control, 80 |

Six sessions each of 3-4 hours. A certificate to hang on newborn babies’ room. | -Full Breast feeding at six months: Intervention group-62.5%, Control- 23.7% |

| 4. Su, 2016 [73] | China, Quasi-experimental study | Participants fluent in Mandarin, more than 20 years, first pregnancy, singleton fetus, couple living together, gestational age more than 39 weeks | -Intervention group with 36 pregnant mother-husband pairs -Control group of 36 with only the pregnant mother |

60-90 minute health education sessions using power-point presentations and models | -Full Breast feeding at six months: Intervention group- 14 of 35 (40%), control group-6 of 34(17.6%) |

Fig. 3.

Forest-plot with fixed-model assumption for the primary outcome

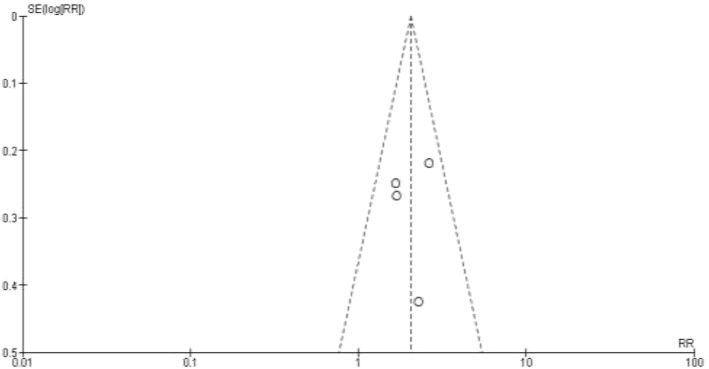

The effect measures of the selected studies yielded an approximately symmetrical Funnel-plot as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot of the studies used in meta-analysis of the primary outcome

The results of the sensitivity analysis have been mentioned in Table 4. Even when the meta-analysis was done with random-model assumption as well as when it was repeated removing one study at a time, the pooled estimates were significantly favoring the interventional groups.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and sub group analysis of the pooled estimate of primary outcome

| Heterogeneity | Number | Risk Ratio | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With fixed-model assumption (four studies) | I2 value- 0% P = 0.46 |

587 | 2.04 | 1.58 to 2.65 |

| With random-model assumption (four studies) | I2 value- 0% P = 0.46 |

587 | 2.04 | 1.57 to 2.65 |

| Fixed-model assumption with Ozlusus 2014 removed | I2 value- 0% P = 0.38 |

509 | 2.14 | 1.59 to 2.89 |

| Random-model assumption with Ozlusus 2014 removed | I2 value- 0% P = 0.38 |

509 | 2.17 | 1.61 to 2.93 |

| Fixed-model assumption with Pisacane 2005 removed | I2 value- 0% P = 0.44 |

307 | 2.25 | 1.66 to 3.07 |

| Random-model assumption with Pisacane 2005 removed | I2 value- 0% P = 0.44 |

307 | 2.21 | 1.63 to 3.01 |

| Fixed-model assumption with Sahip 2007 removed | I2 value- 0% P = 0.81 |

427 | 1.77 | 1.27 to 2.46 |

| Random-model assumption with Sahip 2007 removed | I2 value- 20% P = 0.29 |

427 | 1.76 | 1.27 to 2.44 |

| Fixed-model assumption with Su 2016 removed | I2 value- 0% P = 0.29 |

518 | 2.02 | 1.53 to 2.66 |

| Random-model assumption with Su 2016 removed | I2 value- 0% P = 0.29 |

518 | 2.00 | 1.47 to 2.73 |

Meta-analysis and narrative synthesis of the secondary outcomes

The characteristics of the selected studies for the analysis of secondary outcomes have been summarized in Table 5. The SOF table was prepared for the seven outcomes (Table 2). For four outcomes (EBF at the end of 6 months, EBF at the end of 4 months, full formula feeding within 2 months and support of the father), meta-analysis showed favorable outcomes in the interventional groups than in the control groups. Respectively, the chi-square values and I-square values in the heterogeneity analysis for EBF at the end of 4 months were 0.62 and 0%. For formula feeding within 2 months the respective values were 0.13 and 55%. For the support of father, they were 0.37 and 0%, respectively.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the selected studies for the meta-analysis of the secondary outcomes

| Study | Study | Population | Comparison | Intervention | Selected outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Abbass-Dick 2015 [78] | Canada, Randomized controlled trial | Primiparous mothers with a singleton birth, 18 or more years old, term delivery, with a male partner | 1. Intervention group (107 couples) 2. Control group (107 couples) |

Face to face intervention of approximately 15 minutes. Could refer to materials like workbook, video and a website later | -Support of fathers: Intervention group- 71%, Control group- 52% |

| 2. Raeisi 2014 [75] | Iran, Interventional study | Mother in second trimester, no pregnancy complication or underlying disease | 1. Intervention group (Group A) – 50 couples 2. Control group (Group B)- 50 couples |

Three training sessions including brochures | -Support of fathers: Intervention group-94%, Control- 60% -Knowledge of mothers Intervention group-103 points, Control- 95.71 points |

| 3. Maycock 2013 [76] | Australia Randomized controlled trial | Mother must be more than 18 years, father must be contactable living in Western Australia and willing to involve in child rearing | 1. Intervention group- 358 2. Control group-298 |

Two hour antenatal health education session and a postnatal social support package including printed materials. | -Full formula feeding at six weeks: Intervention group-18.4%, Control- 24.8% |

| 4. Susin 2008 [77] | Brazil, Controlled clinical trial | Couples living in the city of Porto Alegre, infants have no health problems, birth weight equal to or more than 2500 g, have initiated breastfeeding | -Control group (no intervention)- 201 -Intervention group with mother- 192 -Intervention group with both mother and father- 193 |

Health education session with a 18-minute video and a discussion, an explanatory handout was provided | -EBF at four months: Intervention group with mothers- 11.1%, Intervention group with both mother and father-16.5% |

The first three-pooled measures were found to be robust with sensitivity analysis done by repeating with random-model assumption. The effect measure for the “support of the father” became non-significant when the latter model-assumption was used. The occurrence of breastfeeding problems showed a very lower likelihood in the intervention group. The narrative summaries for knowledge of mother on breastfeeding, maternal attitudes towards breastfeeding and the additional narrative summary for the support of father, too demonstrated favorable outcomes in the intervention groups than in the control groups.

The quality of evidence was determined as: low (for one outcome), moderate (for two outcomes), and high (for two outcomes) based on the recommendations of GRADE recommendations.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review with a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of targeting the male partner for the promotion of breastfeeding. The meta-analysis revealed that targeting the fathers is associated with two times the likelihood of getting the baby exclusively breastfed for 6 months. Furthermore, the experimental groups achieved favorable results when the other six outcomes were concerned as well. The systematic review included both randomized controlled trials as well as quasi-experimental trials. The suitability of the inclusion of the latter in systematic reviews have been highlighted in modern literature [80].

The quality of this systematic review and meta-analysis was ensured with several steps. Firstly, the data search was done without restricting to a time period. It is mentioned that searching all available data as a better strategy in systematic reviews [81]. The duration of EBF was recommended to be 6 months from the beginning of twenty-first century and until then, there had been a debate about shorter duration [82, 83]. Many of the previously documented literature had no uniformity of considering EBF period as 6 months [84]. Since then it was decided to include another secondary outcome for a shorter duration (i.e. EBF for 4 months).

Risk of bias estimates were not done by averaging the several components of the bias estimates but by utilizing recommended guidelines. [42, 45, 85] Not surprisingly, in the majority of studies, blinding had not been possible and as a result they were categorized as high-risk for the performance bias. Strict categorizing criteria were adhered to in the estimation of bias. As an example, when the allocations were done based on time period of delivery of baby, the high-risk categorization for selection bias was given and down-grading was done in determining the quality of evidence in the SoF table. To improve the validity of the results, RR was used as the effect measure instead of odds ratio [51, 52].

It is recommended to consider the statistical, clinical, and methodological heterogeneity in interpreting the quality of meta-analysis [48, 86, 87]. The statistical heterogeneity of the studies were seemingly acceptable based on I-square percentages and chi-square values [42, 48–50]. Only the I-square value was marginally high for one of the secondary outcomes (i.e. for the support of father). Clinical heterogeneity does not seemingly influence the results as most of the outcomes for which the meta-analyses were done are objectively categorically coded (as an example, whether EBF continued for 6 months or not). In all studies, the periods of interventions did not extend beyond the neonatal period. All outcome measurements had been done after 2 months of the birth. Measures to minimize methodological-bias were adhered to in selection of the studies and in the expression of risk of bias of each study. Furthermore, the control groups of the studies had been recruited from similar settings. Even though “fatherhood” is influenced by the culture, universally, fathers care for the well-being of the family and children [88, 89]. Hence, though the degree of involvement of a father may vary in nutrition related affairs of the newborn, its direction in all settings can be assumed as towards getting more benefits to the baby.

An extensive sensitivity analysis has been done in the present manuscript. Sensitivity analysis has been defined as “a method to determine the robustness of an assessment by examining the extent to which results are affected by changes in methods, models, values of unmeasured variables, or assumptions.” [90] Since all the measures except one in the sensitivity analysis point towards significant favorable effects of targeting fathers, the robustness of the conclusions become high.

Targeting fathers was effective in increasing likelihood of EBF at the end of 6 months as well as at the end of 4 months. RR for the EBF at 6 months is higher than that of the figure at 4 months and double as compared to the control group. In other words, it is associated with a higher probability of uninterrupted provision of breast milk enabling the child to get its benefits [1–6]. This finding can be evaluated further using the fourth outcome in the SoF table which is the support extended by the father for breastfeeding. High quality evidence was seen in the meta-analysis as well as the narrative synthesis showing the favorable influence of targeting fathers on the prospective support they render. When fathers get to know the scientific evidence on the benefits of breastfeeding, it can be postulated that they would encourage the partner to continue this course. This would have resulted in increasing their support as well as indirectly prolonging the duration of EBF.

The prevalence of full-formula-feeding was less in the intervention group. This finding can be discussed coupling to the sixth outcome (i.e. occurrence of breastfeeding related problems). When fathers are educated on breastfeeding, due to their support (i.e. fourth outcome), better positioning and attachment of the baby to the breast during feeding would be facilitated. Lesser lactation-related problems would ensure not opting for the formula milk. Furthermore, this would be facilitated by the fact that mothers’ knowledge and attitudes on breastfeeding becoming more favorable with the intervention (i.e. fifth and seventh outcomes).

The effect of the intervention on mothers’ knowledge and on favorable attitudes can be described with several explanations. The mutual discussions that occur in the household with the partners would improve mothers’ knowledge. Secondly, the positive perception of the partner’s attitude on breastfeeding would foster the mothers’ attitudes as well. This is compatible with the global literature [27].

In the present review, all seven outcomes, including EBF rates, were favorably influenced by targeting the expectant fathers for promotion of breast milk. This review adds value to the attempts made by the healthcare systems in involving expectant and new fathers in the interventions for the promotion of breastfeeding. More emphasis could be given for the male-partner domain of the awareness packages that are done in the ante-natal and neonatal periods for the promotion of breastfeeding. Since the breastfeeding is associated with mitigation of communicable diseases as well as prospective occurrence of NCDs, targeting fathers becomes a cost-effective strategy which yields the effects through prolonged duration of EBF. Breastfeeding related indicators are used to determine the improvement of the health status of a country [91]. Furthermore, longer duration of breastfeeding is recommended as a “smart investment” in achieving Sustainable Developmental Goals [92]. Hence the intervention of this review would ensure better placement of countries in relation to health indicators.

There were several limitations of the review. Firstly, the results could not be standardized for the quality of the interventions. This was because the review was done on different experimental studies which were done on different settings using different intervention packages. To compensate for its impact, seven outcome measures which are supposed to be linked with the awareness on general-aspects related to breastfeeding were selected. Furthermore in selecting the studies, special emphasis was given to the intervention-related details. Since the determination of the risk of bias and grading of the quality of evidence include judgmental decision-making, undue influence of being “subjective,” could not be totally excluded. Yet, several steps like independent assessment by several reviewers, contacting the GRADE support group for clarifications were done. Another is that, in measuring the mothers’ knowledge (fifth outcome), different tools were used. To minimize its impact, the narrative summary was made to focus on the “change of knowledge” rather than on the raw scores.

Conclusions

Targeting fathers in the antenatal and postnatal periods of the baby: improves EBF at 6 months (RR = 2.04, CI = 1.58–2.65) and EBF at 4 months (RR = 1.52, CI = 1.14 to 2.03). In addition it decreases the probability of full-formula-feeding at 2 months (RR = 0.69, CI = 0.52 to 0.93) and the occurrence of breastfeeding related problems (RR = 0.24, CI = 0.10 to 0.57). Furthermore it increases the support extended by the father in breastfeeding related issues (RR = 1.43, CI = 1.22 to 1.68). Mothers’ knowledge on breastfeeding and the favorable attitudes on breastfeeding are augmented with the intervention done on fathers (P ≤; 0.001).

The conclusions are robust as suggested by the sensitivity analysis. The quality of evidence ranges from “low” to “high” for different outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Authors like to acknowledge Nicola Richards of Melbourne School of Global and Population Health, University of Melbourne for her valuable inputs in revising the manuscript.

Funding

The review was self-funded and was not funded by a third party.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the review are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

PKBM was involved in the conceptualization of the review, literature search, data extraction, data analysis and drafting of the initial manuscript. MW, SM and C were involved in the conceptualization of the review, literature search, data extraction, data analysis and editing the manuscript. S, MFM and PM were involved in conceptualization of the review, literature search, data extraction, and editing the manuscript. SJ involved in revising of the manuscript. All authors read the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Pasyodun Koralage Buddhika Mahesh, Phone: 094-772618059, Email: buddhikamaheshpk@gmail.com.

Moraendage Wasantha Gunathunga, Email: wasantg@commed.cmb.ac.lk.

Suriyakumara Mahendra Arnold, Email: mahendra_arnold@yahoo.com.

Chintha Jayasinghe, Email: chinthaj@yahoo.com.

Sisira Pathirana, Email: sisira_pathirana@yahoo.com.

Mohamed Fahmy Makarim, Email: mfmmakarim@gmail.com.

Pradeep Malaka Manawadu, Email: malaka102mfc@yahoo.com.

Sameera Jayan Senanayake, Email: sjsenanayake@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Motee A, Ramasawmy D, Pugo-Gunsam P, Jeewon R. An assessment of the breastfeeding practices and infant feeding pattern among mothers in Mauritius. J Nutr Metab. 2013;2013:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2013/243852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuchenbecker J, Jordan I, Reinbott A, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and its effect on growth of Malawian infants: results from a cross-sectional study. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2015;35(1):14–23. doi: 10.1179/2046905514Y.0000000134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogunrinade SA. Effects of exclusive breastfeeding on babies health in Ife Central local government of Osun State. Int J Nutr Metab. 2014;6(1):1–8. doi: 10.5897/IJNAM2013.0156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker W. Allan, Iyengar Rajashri Shuba. Breast milk, microbiota and intestinal immune homeostasis. Pediatric Research. 2014;77(1-2):220–228. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motee A, Jeewon R. Importance of Exclusive Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding among Infants. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci J. 2014;2(2):56–72. doi: 10.12944/CRNFSJ.2.2.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wojcicki JM, Heyman MB, Elwan D, Lin J, Blackburn E, Epel E. Early exclusive breastfeeding is associated with longer telomeres in Latino preschool children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(2):397–405. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.115428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singhal A. The role of infant nutrition in the global epidemic of non-communicable disease. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75(02):162–168. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelishadi R, Farajian S. The protective effects of breastfeeding on chronic non-communicable diseases in adulthood: a review of evidence. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3(1):3. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.124629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahesh PKB, Gunathunga MW, Jayasinghe S, et al. Financial burden of survivors of medically-managed myocardial infarction and its association with selected social determinants and quality of life in a lower middle income country. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):251. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0687-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahesh PKB, Gunathunga MW, Jayasinghe S, Arnold SM, Liyanage SN. Factors influencing pre-stroke and post-stroke quality of life among stroke survivors in a lower middle-income country. Neurol Sci. 2018;39(2):287–295. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-3172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en/. Published 2017. Accessed Nov 9 2017.

- 13.Cai X, Wardlaw T, Brown DW. Global trends in exclusive breastfeeding. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heymann J, Raub A, Earle A. Breastfeeding policy: a globally comparative analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(6):398–406. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith HA, Becker GE. Early additional food and fluids for healthy breastfed full-term infants. In: Smith HA, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. In: Kramer MS, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbass-Dick J, Dennis C-L. Breast-feeding Coparenting framework. Fam Community Health. 2017;40(1):28–31. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doğa Öcal F, Vural Yılmaz Z, Ceyhan M, Fadıl Kara O, Küçüközkan T. Early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding: factors influencing the attitudes of mothers who gave birth in a baby-friendly hospital. J Turkish Soc Obstet Gynecol. 2017:1–9. 10.4274/tjod.90018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Susiloretni KA, Hadi H, Prabandari YS, Soenarto YS, Wilopo SA. What works to improve duration of exclusive breastfeeding: lessons from the exclusive breastfeeding promotion program in rural Indonesia. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(7):1515–1525. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1656-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garbarino F, Morniroli D, Ghirardi B, et al. Prevalence and duration of breastfeeding during the first six months of life: factors affecting an early cessation. La Pediatr Medica e Chir. 2013;35(5). 10.4081/pmc.2013.30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Swigart Tessa M., Bonvecchio Anabelle, Théodore Florence L., Zamudio-Haas Sophia, Villanueva-Borbolla Maria Angeles, Thrasher James F. Breastfeeding practices, beliefs, and social norms in low-resource communities in Mexico: Insights for how to improve future promotion strategies. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown A, Davies R. Fathers’ experiences of supporting breastfeeding: challenges for breastfeeding promotion and education. Matern Child Nutr. 2014;10(4):510–526. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rempel LA, Rempel JK. The breastfeeding team: the role of involved fathers in the breastfeeding family. J Hum Lact. 2011;27(2):115–121. doi: 10.1177/0890334410390045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett AE, McCartney D, Kearney JM. Views of fathers in Ireland on the experience and challenges of having a breast-feeding partner. Midwifery. 2016;40:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter T, Cattelona G. Ann. Breastfeeding initiation and duration in first-time mothers: exploring the impact of father involvement in the early post-partum period. Heal Promot Perspect. 2014;4(2):132–136. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2014.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu J, Chan WCS, Zhou X, Ye B, He H-G. Predictors of breast feeding self-efficacy among Chinese mothers: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Midwifery. 2014;30(6):705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X, Gao L, Ip W-Y, Sally Chan WC. Predictors of breast feeding self-efficacy in the immediate postpartum period: a cross-sectional study. Midwifery. 2016;41:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robert E, Coppieters V, Swennen B, Dramaix M. Determinants of breastfeeding in the Brussels Region. Rev Med Brux. 36(2):69–74 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26164964. [PubMed]

- 30.Yourkavitch JM, Alvey JL, Prosnitz DM, Thomas JC. Engaging men to promote and support exclusive breastfeeding: a descriptive review of 28 projects in 20 low- and middle-income countries from 2003 to 2013. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s41043-017-0127-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emmott Emily H., Mace Ruth. Practical Support from Fathers and Grandmothers Is Associated with Lower Levels of Breastfeeding in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0133547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karande S, Perkar S. Do fathers’ attitudes support breastfeeding? A cross-sectional questionnaire-based study in Mumbai, India. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66(1):30. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.110861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balogun OO, O’Sullivan EJ, McFadden A, et al. Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. In: Balogun OO, et al., editors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Guideline: protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding in facilities providing maternity and newborn services. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [PubMed]

- 35.Ganeshkumar P, Gopalakrishnan S. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2013;2(1):9. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.109934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lumbiganon P, Martis R, Laopaiboon M, Festin MR, Ho JJ, Hakimi M. Antenatal breastfeeding education for increasing breastfeeding duration. In: Lumbiganon P, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell-Box KM, Braun KL. Impact of male-partner-focused interventions on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and continuation. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(4):473–479. doi: 10.1177/0890334413491833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aussems M-CE, Boomsma A, Snijders TAB. The use of quasi-experiments in the social sciences: a content analysis. Qual Quant. 2011;45(1):21–42. doi: 10.1007/s11135-009-9281-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2006;13(1):16–23. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johansen M, Thomsen SF. Guidelines for reporting medical research: a critical appraisal. Int Sch Res Not. 2016;2016:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2016/1346026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):579. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conway A, Clarke MJ, Treweek S, et al. Summary of findings tables for communicating key findings of systematic reviews. In: Conway A, et al., editors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JH, Kim TK, In J, Lee DK, Lee S, Kang H. Assessment of risk of bias in quasi-randomized controlled trials and randomized controlled trials reported in the Korean journal of anesthesiology between 2010 and 2016. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2017;70(5):511. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2017.70.5.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waddington H, Aloe AM, Becker BJ, et al. Quasi-experimental study designs series—paper 6: risk of bias assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias) J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.GRADE working group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328(7454):1490–0. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bown MJ, Sutton AJ. Quality control in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40(5):669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melsen WG, Bootsma MCJ, Rovers MM, Bonten MJM. The effects of clinical and statistical heterogeneity on the predictive values of results from meta-analyses. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(2):123–129. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Israel H, Richter RR. A guide to understanding meta-analysis. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2011;41(7):496–504. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akobeng AK. Understanding systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(8):845–848. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.058230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schechtman E. Odds ratio, relative risk, absolute risk reduction, and the number needed to treat—which of these should we use? Value Heal. 2002;5(5):431–436. doi: 10.1046/J.1524-4733.2002.55150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campbell M, Thomson H, Katikireddi SV, Sowden A. Reporting of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews of public health interventions: a methodological assessment. Lancet. 2016;388:S34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32270-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J Dev Eff. 2012;4(3):409–429. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2012.710641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langendam MW, Akl EA, Dahm P, Glasziou P, Guyatt G, Schünemann HJ. Assessing and presenting summaries of evidence in Cochrane reviews. Syst Rev. 2013;2(1):81. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schroll JB, Moustgaard R, Gøtzsche PC. Dealing with substantial heterogeneity in Cochrane reviews. Cross-sectional study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brugha TS, Matthews R, Morgan Z, Hill T, Alonso J, Jones DR. Methodology and reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies in psychiatric epidemiology: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(6):446–453. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.098103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Zhao-Yang, Zhao Keke, Zheng Jingwei, Rossmiller Brian, Ildefonso Cristhian, Biswal Manas, Zhao Pei-quan. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Complement Factor H I62V Polymorphism and Risk of Polypoidal Choroidal Vasculopathy in Asian Populations. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e88324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolfberg AJ, Michels KB, Shields W, O’Campo P, Bronner Y, Bienstock J. Dads as breastfeeding advocates: results from a randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):708–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maycock BR, Scott JA, Hauck YL, et al. A study to prolong breastfeeding duration: design and rationale of the parent infant feeding initiative (PIFI) randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):159. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hannula LS, Kaunonen ME, Puukka PJ. A study to promote breast feeding in the Helsinki metropolitan area in Finland. Midwifery. 2014;30(6):696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Susiloretni KA, Krisnamurni S, Sunarto, WEidiyanto SYD, Yazid A, Wilopo SA. The effectiveness of multilevel promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in rural Indonesia. Am J Health Promot. 2013;28(2):e44–e55. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120425-QUAN-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wockel A, Abou-Dakn M. Influence of the partner on breastfeeding duration and breast diseases during lactation. Results of an intervention study. Gynakol Prax. 2009;33(4):643–9.

- 64.Bich TH, Hoa DTP, Ha NT, Vui LT, Nghia DT, Målqvist M. Father’s involvement and its effect on early breastfeeding practices in Viet Nam. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(4):768–777. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Furman L, Killpack S, Matthews L, Davis V, O’Riordan MA. Engaging Inner-City fathers in breastfeeding support. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(1):15–20. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2015.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tohotoa J, Maycock B, Hauck Y, Howat P, Burns S, Binns C. Supporting mothers to breastfeed: the development and process evaluation of a father inclusive perinatal education support program in Perth, Western Australia. Health Promot Int. 2011;26(3):351–361. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ingram J, Johnson D. A feasibility study of an intervention to enhance family support for breast feeding in a deprived area in Bristol, UK. Midwifery. 2004;20(4):367–379. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stremler J, Lovera D. Insight from a breastfeeding peer support pilot program for husbands and fathers of Texas WIC participants. J Hum Lact. 2004;20(4):417–422. doi: 10.1177/0890334404267182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Susin LR, Giugliani ER, Kummer SC, Maciel M, Simon C, da Silveira LC. Does parental breastfeeding knowledge increase breastfeeding rates? Birth. 1999;26(3):149–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1999.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bich TH, Hoa DTP, Målqvist M. Fathers as supporters for improved exclusive breastfeeding in Viet Nam. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(6):1444–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pisacane A. A controlled trial of the Father’s role in breastfeeding promotion. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):e494–e498. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Özlüses E, Çelebioglu A. Educating fathers to improve breastfeeding rates and paternal-infant attachment. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(8):654–657. doi: 10.1007/s13312-014-0471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Su M, Ouyang Y-Q. Father’s role in breastfeeding promotion: lessons from a quasi-experimental trial in China. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(3):144–149. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2015.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.SAHIP Y, Molzan Turan J. education for expectant fathers in workplaces in Turkey. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39(06). 10.1017/S0021932007002088. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Raeisi K, Shariat M, Nayeri F, Raji F, Dalili H. A single center study of the effects of trained fathers’ participation in constant breastfeeding. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52(9):694–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maycock B, Binns CW, Dhaliwal S, et al. Education and support for fathers improves breastfeeding rates. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(4):484–490. doi: 10.1177/0890334413484387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosane Odeh Susin L, Regina Justo Giugliani E. Inclusion of fathers in an intervention to promote breastfeeding: impact on breastfeeding rates. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(4):386–392. doi: 10.1177/0890334408323545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abbass-Dick J, Stern SB, Nelson LE, Watson W, Dennis C-L. Coparenting breastfeeding support and exclusive breastfeeding: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):102–110. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Suomela A, Verronen P, Tamminen T, Nurmi R, Turunen L. The father, a very important figure if breast feeding is to succeed. A successful Tampere project. Katilolehti. 1982;87(11):332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rockers PC, Tugwell P, Grimshaw J, et al. Quasi-experimental study designs series–paper 12: strengthening global capacity for evidence synthesis of quasi-experimental health systems research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meehan S, Beck CR, Mair-Jenkins J, Leonardi-Bee J, Puleston R. Maternal obesity and infant mortality: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):863–871. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ng Charmaine S, Dibley Michael J, Agho Kingsley E. Complementary feeding indicators and determinants of poor feeding practices in Indonesia: a secondary analysis of 2007 Demographic and Health Survey data. Public Health Nutrition. 2011;15(05):827–839. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review. World Heal Organ. 2001;47. 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.

- 84.Sciacca JP, Dube DA, Phipps BL, Ratliff MI. A breast feeding education and promotion program: effects on knowledge, attitudes, and support for breast feeding. J Community Health. 1995;20(6):473–490. doi: 10.1007/BF02277064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Higgins JPT, Green S, ed. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [Updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- 86.West SL, Gartlehner G, Mansfield AJ, et al. Comparative Effectiveness Review Methods: Clinical Heterogeneity. Agency Healthc Res Qual. 2010. Methods Research Paper. AHRQ Publication No. 10-EHC070-EF. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/. [PubMed]

- 87.Gagnier JJ, Moher D, Boon H, Beyene J, Bombardier C. Investigating clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews: a methodologic review of guidance in the literature. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cruz RA, King KM, Widaman KF, Leu J, Cauce AM, Conger RD. Cultural influences on positive father involvement in two-parent Mexican-origin families. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(5):731–740. doi: 10.1037/a0025128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roopnarine JL, editor. Fathers across Cultures: The importance, roles, and diverse practices of dads. Santa Barbara: Praeger/ABC-Praeger/ABC-CLIO; 2015.

- 90.Thabane L, Mbuagbaw L, Zhang S, et al. A tutorial on sensitivity analyses in clinical trials: the what, why, when and how. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Issaka AI, Agho KE, Renzaho AM. Prevalence of key breastfeeding indicators in 29 sub-Saharan African countries: a meta-analysis of demographic and health surveys (2010–2015) BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e014145. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.World Bank. Breastfeeding: A Smart Investment for Reaching the Sustainable Development Goals. http://blogs.worldbank.org/health/breastfeeding-smart-investment-reaching-sustainable-development-goals. Published 2016. Accessed 15 Nov 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the review are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.