Abstract

This study shows that methyl 2-aminobenzoate (also known as methyl anthranilate, hereafter MA) undergoes direct photolysis under UVC and UVB irradiation and that its photodegradation is further accelerated in the presence of H2O2. Hydrogen peroxide acts as a source of hydroxyl radicals (·OH) under photochemical conditions and yields MA hydroxyderivatives. The trend of MA photodegradation rate vs. H2O2 concentration reaches a plateau because of the combined effects of H2O2 absorption saturation and ·OH scavenging by H2O2. The addition of chloride ions causes scavenging of ·OH, yielding Cl2·− as the most likely reactive species, and it increases the MA photodegradation rate at high H2O2 concentration values. The reaction between Cl2·− and MA, which has second-order rate constant = (4.0 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1·s−1 (determined by laser flash photolysis), appears to be more selective than the ·OH process in the presence of H2O2, because Cl2·− undergoes more limited scavenging by H2O2 compared to ·OH. While the addition of carbonate causes ·OH scavenging to produce CO3·− ( = (3.1 ± 0.2) × 108 M−1·s−1), carbonate considerably inhibits the photodegradation of MA. A possible explanation is that the elevated pH values of the carbonate solutions make H2O2 to partially occur as HO2−, which reacts very quickly with either ·OH or CO3·− to produce O2·−. The superoxide anion could reduce partially oxidised MA back to the initial substrate, with consequent inhibition of MA photodegradation. Fast MA photodegradation is also observed in the presence of persulphate/UV, which yields SO4·− that reacts effectively with MA ( = (5.6 ± 0.4) × 109 M−1·s−1). Irradiated H2O2 is effective in photodegrading MA, but the resulting MA hydroxyderivatives are predicted to be about as toxic as the parent compound for aquatic organisms (most notably, fish and crustaceans).

Keywords: advanced oxidation processes, methyl anthranilate, methyl 2-aminobenzoate, hydrogen peroxide, photodegradation intermediates, emerging contaminants

1. Introduction

Methyl 2-aminobenzoate (MA, C8H9NO2) is a clear liquid that occurs in many essential oils. It has a melting point of 24 °C, a boiling point of 256 °C, and a density of 1.17 g·mL−1 [1]. MA can be found in Concord grapes, jasmine, bergamot, lemon, orange, and strawberries, and it is used as bird repellent in the protection of food crops such as corn, sunflower, rice, and fruits [2]. MA is also employed to prevent birds from accessing oil spill–contaminated water or water pools near airports, in the latter case reducing the risk of collision with aircraft [3]. MA is used as well for the flavouring of candies, soft drinks, chewing gum, and medicines [4], which suggests that it has limited toxicity towards mammals, including humans. Its LD50 (lethal dose 50) values for rats and rabbits are in fact in the g/(Kg body weight) range for either oral or dermal uptake [5]. Despite these apparently favourable features, MA shows non-negligible toxicity for aquatic organisms, with LC50 (lethal concentration 50 in water, i.e., acute toxicity) values of 20–30 mg·L−1 for fish [6]. More importantly, it can cause chronic effects to both fish and crustaceans at 10–70 µg·L−1 levels [7,8,9]. Therefore, toxicity to fish is to be taken into account when using MA to protect aquaculture facilities from predation by birds [10]. MA is also poorly biodegradable, little volatile, and it undergoes limited partitioning to solids. Moreover, its predicted hydrolysis time is in the range of several months to some years [11]. Following ingestion as a food additive and excretion, this compound is unlikely to be eliminated from the aqueous phase of the wastewater treatment plants (estimates for MA elimination are in the range of a few percent, mostly accounted for by sludge adsorption) [11]. Therefore, MA could easily reach surface water environments. Unfortunately, concentration data of MA in surface waters are extremely difficult to be found in the literature, as are data concerning the elimination of MA from aqueous solutions including wastewater.

Poor elimination during wastewater treatment is a widespread feature of several emerging substances used as drugs, fragrances, fire extinguishers etc. These compounds can be found in surface waters at significant levels due to point-source emission at the treatment plant outlets [12,13]. A likely future development in wastewater treatment will be the update of the existing plants to enable the removal of emerging contaminants. As technological upgrade options, Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) are among the best promising tools [14,15]. Most AOPs are based on the thermal, electrochemical, photochemical or sonochemical generation of hydroxyl radicals (·OH), in the homogeneous phase or in heterogeneous systems (e.g., heterogeneous photocatalysis, [16]). The ·OH radicals are very strong oxidants and they can react with a very wide variety of organic and inorganic molecules, including pollutants. The relevant reactions include electron or hydrogen transfer, as well as addition to double bonds and aromatic rings [17]. Among AOPs, the UV irradiation of hydrogen peroxide (hereafter, H2O2/UV) presents several advantages including the elevated quantum yield of ·OH photogeneration (the reaction H2O2 + hν → 2 ·OH has ~ 0.5 and ~ 1 [17,18]), the low cost of H2O2, and the formation of rather innocuous reaction by-products from H2O2 itself (mostly H2O and O2) [19,20]. H2O2 is also water-miscible and it is relatively safe to store and transport pending some precautions, but its water solutions need to be added with stabilisers (e.g., stannate, pyrophosphate, nitrate, colloidal silicate) that will finally end up in the water undergoing treatment [18]. Moreover, toxic or otherwise harmful photodegradation intermediates may be formed when dealing with the treatment of certain organic pollutants [21]. Another issue is that ·OH reacts not only with the target contaminant, but also with natural organic matter (NOM) and with inorganic anions that occur in aqueous solution. While NOM is mostly a ·OH quencher, in the case of some anions the framework is more complicated because their oxidation by ·OH yields reactive radical species, which are less reactive than ·OH itself but could still initiate some degradation processes on their own. Examples are the ·OH-induced formation of the carbonate radical (CO3·−) from carbonate and bicarbonate, of dichloride (Cl2·−) from chloride, of dibromide (Br2·−) from bromide, and of nitrogen dioxide (·NO2) from nitrite [22]. Moreover, one of the possibilities to reduce the consumption of reactive species by the organic and inorganic components of natural waters is to replace ·OH with the more selective sulphate radical, SO4·−, which reacts with several pollutants but undergoes less interference from NOM and inorganic anions compared to ·OH [23]. To produce SO4·−, it is often sufficient to replace H2O2 with the analogous peroxide persulphate (S2O82−) in comparable processes [23,24].

The goal of this work is to study the photoinduced degradation of MA under UV irradiation (direct UVC photolysis, here used as benchmark) and with H2O2/UV and persulphate/UV treatments, as well as to assess the effect on the process of common inorganic anions such as chloride and carbonate. To better assess the effect of the added anions, the reactivity of CO3·− and Cl2·− with MA was studied by using the nanosecond laser flash photolysis technique. Because MA is not harmless to aquatic environments, this study investigates the following: (i) whether and to what extent MA could be photodegraded under AOP conditions, also in the presence of inorganic anions such as chloride and carbonate; and (ii) the potential of MA photodegradation to produce intermediates that might have higher impact than the parent compound, and that could be formed during the AOP removal of MA and/or other contaminants.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. MA Photodegradation by UV and H2O2/UV

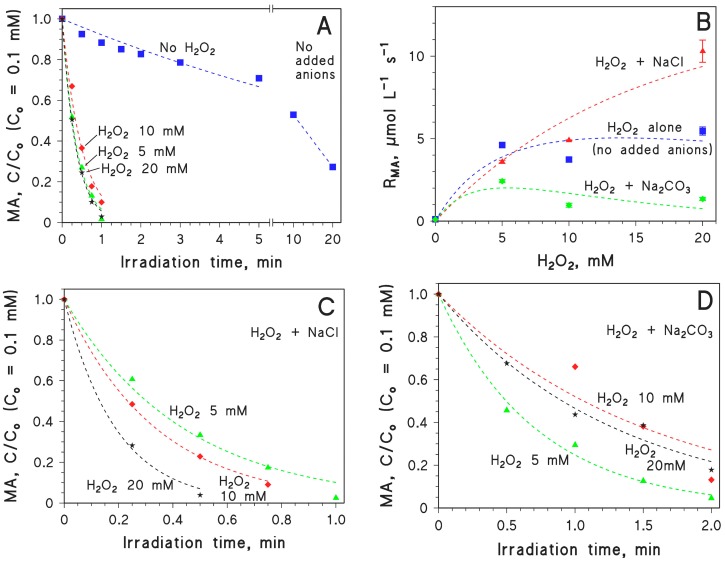

The photoinduced degradation of 0.1 mM MA was first studied under UVC irradiation alone (lamp maximum emission at 254 nm) and under UVC irradiation in the presence of different concentration values of H2O2 (see Figure 1 for the absorption spectra of MA and H2O2). The MA time evolution under these conditions is reported in Figure 2A, while Figure 2B reports the trend of the photodegradation rate of MA (RMA) as a function of the H2O2 concentration. Table 1 reports the pseudo-first order photodegradation rate constants of MA (kMA) for this and other series of experiments. Note that RMA = kMA [MA]o, where [MA]o = 0.1 mM is the initial concentration of MA.

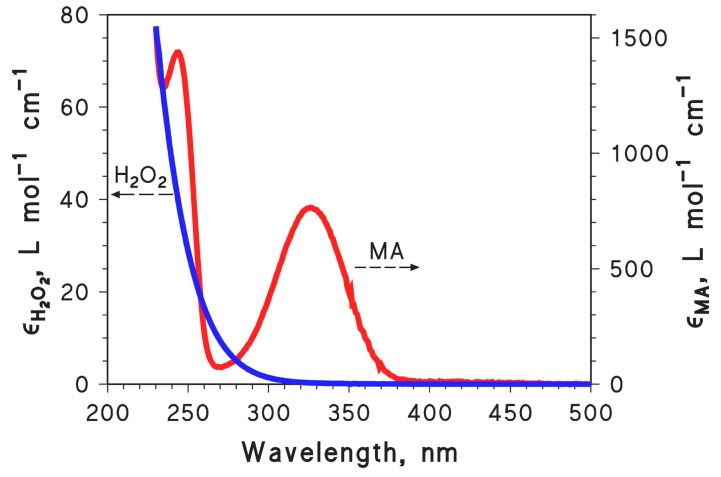

Figure 1.

Absorption spectra (molar absorption coefficients) of methyl 2-aminobenzoate (MA) (right Y-axis) and H2O2 (left Y-axis).

Figure 2.

(A) Time trend of 0.1 mM MA under UVC irradiation, alone or in the presence of different concentration values of H2O2 (varied in the range of 0–20 mM); (B) Initial photodegradation rates of 0.1 mM MA (RMA) as a function of H2O2 concentration, alone or in the presence of 0.1 M NaCl or 0.1 M Na2CO3; (C) Time trend of 0.1 mM MA in the presence of 0.1 M NaCl and different concentration values of H2O2 (varied in the range of 5–20 mM); (D) Time trend of 0.1 mM MA in the presence of 0.1 M Na2CO3 and different concentration values of H2O2 (varied in the range of 5–20 mM). The pH values of the studied systems were ~neutral, with the exception of the systems containing Na2CO3. The error bars shown in panel (B) represent the uncertainty associated to the calculation of the photodegradation rates by fitting the MA time trend data with a pseudo-first order kinetic model (intra-series variability). In several cases the error bars were smaller than the data points. The reproducibility between experimental replicas (inter-series variability) was in the range of 15–20%.

Table 1.

Pseudo-first order photodegradation rate constants of MA (kMA) in the different irradiation experiments. The initial concentration values of hydrogen peroxide, persulphate, chloride and carbonate are also reported. The error bounds to the kMA data represent the sigma-level uncertainty of the pseudo-first order kinetic model. In all the cases the initial concentration of MA was 0.1 mM.

| [H2O2], mM | [S2O82−], mM | [Cl−], mM | [CO32−], mM | kMA, min−1 (±σ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | / | / | / | 0.081 ± 0.007 |

| 5 | / | / | / | 2.72 ± 0.12 |

| 10 | / | / | / | 2.03 ± 0.13 |

| 20 | / | / | / | 2.87 ± 0.09 |

| 5 | / | 100 | / | 2.29 ± 0.16 |

| 10 | / | 100 | / | 2.97 ± 0.06 |

| 20 | / | 100 | / | 5.30 ± 0.34 |

| 5 | / | / | 100 | 1.40 ± 0.08 |

| 10 | / | / | 100 | 0.652 ± 0.121 |

| 20 | / | / | 100 | 0.764 ± 0.049 |

| / | 0 | / | / | 0.106 ± 0.007 |

| / | 1 | / | / | 0.133 ± 0.031 |

| / | 5 | / | / | 0.598 ± 0.018 |

| / | 10 | / | / | 7.09 ± 0.16 |

Some MA photodegradation with a half-life time of approximately 10 min took place in the absence of H2O2, due to MA direct photolysis. The direct photolysis quantum yield of MA was calculated as follows [25]:

| (1) |

where is the incident spectral photon flux density of the lamp and is the absorbance of 0.1 mM MA. The photolysis quantum yield was measured in separate experiments under monochromatic irradiation (at 254 and 325 nm) and under broadband irradiation (see Supplementary Material for the detailed results). The values obtained in the different conditions are in the order of magnitude of 10−3. The value at 254 nm ( = 3.8 × 10−3) is the most relevant to our steady irradiation experiments, and a decrease was observed in the values of as the irradiation wavelength increased. Therefore, when applying artificial irradiation, the UVC spectral range and in particular the radiation at 254 nm (very near the UVC absorption maximum of MA, see Figure 1) appears to be the most suitable option to induce MA direct photolysis.

The addition of H2O2 considerably accelerated the photodegradation of MA, and relatively similar kinetics were obtained in the H2O2 concentration range of 5–20 mM. A plateau trend of RMA vs. [H2O2] is apparent in Figure 2B, and in principle it might be accounted for by two different phenomena: (i) saturation of H2O2 absorption with increasing H2O2 concentration; and (ii) offset between photoinduced ·OH generation, and ·OH scavenging by H2O2 itself. The first effect depends on the absorbance of H2O2. Considering ~ 15 L·mol−1·cm−1 and assuming b = 2 cm as the optical path length inside the irradiated solutions, the absorbance of the studied H2O2 solutions was approximately 0.15 (5 mM H2O2), 0.3 (10 mM), and 0.6 (20 mM). The absorbance of 0.1 mM MA at 254 nm is ~ 0.2, and the fraction of radiation absorbed by H2O2 in the irradiated systems can be calculated as follows [25]:

| (2) |

On this basis, the values of as a function of the H2O2 concentration are 0.24 (H2O2 5 mM), 0.41 (H2O2 10 mM), and 0.63 (H2O2 20 mM). Because the lamp radiation can be considered as monochromatic as a first approximation, these values are directly proportional to the formation rate of ·OH produced by the irradiation of H2O2 ( ∝ ). The direct proportionality constant between and includes the formation quantum yield of ·OH by irradiated H2O2 and the incident photon flux in solution, which are constant values that can be included into a proportionality parameter (as ). The photogenerated ·OH can react with either MA or H2O2, and in the latter case the second-order reaction rate constant is = 2.7 × 107 M−1·s−1 [26]. By assuming as the (unknown) second-order reaction rate constant between ·OH and MA, the competition kinetics between MA and H2O2 yields the following results for the MA photodegradation rate ():

| (3) |

With the known values of ~ 15 M−1·cm−1, ~ 0.2, [MA] = 0.1 mM and = 2.7 × 107 M−1·s−1, it was possible to fit reasonably well the vs. [H2O2] experimental data reported in Figure 2B (see dashed curve in the figure). The fit results suggested that would be about two orders of magnitude higher than . This means that the reaction of ·OH with H2O2 is expected to prevail over that with 0.1 mM MA for [H2O2] > 10 mM, which is right within the investigated range of H2O2 concentrations.

2.2. Effect of Inorganic Anions on MA Photodegradation

The effect of anions commonly occurring in surface waters, and most notably of chloride and carbonate, on the photodegradation of MA induced by H2O2/UV was studied upon UVC irradiation of MA, H2O2, and, where relevant, NaCl or Na2CO3.

The time evolution of 0.1 mM MA in the presence of 0.1 M NaCl and different concentration values of H2O2 is reported in Figure 2C, and the corresponding photodegradation rates are reported in Figure 2B. The figure shows that MA photodegradation became progressively faster as the H2O2 concentration increased and, differently from the previous case (MA + H2O2 + UV, without chloride), there was no obvious plateau trend. The experimental rate data could be fitted well with an equation of the form , where is a constant proportionality factor (see the dashed curve in Figure 2B). In this case it seems that the observed trend just mirrored the photon absorption by H2O2, with no need to invoke an additional competition kinetics between MA, H2O2 and the reactive transient species. Moreover, at elevated H2O2 concentration the photodegradation of MA was considerably faster in the presence of 0.1 M NaCl than in the absence of chloride. These pieces of evidence suggest that the prevailing reactive species in the MA/H2O2/Cl−/UV system is very unlikely to be ·OH, which is expected to produce a plateau trend as per the above discussion. A different transient species should rather be involved, inducing competition kinetics between MA and H2O2 to a far lesser extent than ·OH. This reactive transient, provisionally indicated here as X, should react with MA and H2O2 in such a way that . If this condition is met, one has < 1 in Equation (4), which differs from Equation (3) in that the ·OH-based terms are replaced by X-based ones:

| (4) |

In the presence of ·OH + Cl−, the following reactions may take place [26,27,28]:

| ·OH + Cl− ⇆ HOCl·− [Keq,5 = 0.70 M−1] | (5) |

| HOCl−· + H+ ⇆ H2O + Cl· [Keq,6 = 1.6×107 M−1] | (6) |

| Cl· + Cl− ⇆ Cl2·− [Keq,7 = 1.9×105 M−1] | (7) |

Based on the above reactions, potential X-species in the system are HOCl·−, Cl·, and Cl2·−. The reactivity of Cl2·− can be studied by laser flash photolysis, thus one can check the possible involvement of Cl2·− in MA photodegradation by measuring .

In the H2O2/Na2CO3/UV system with 0.1 M Na2CO3, the photodegradation of MA did not accelerate when increasing [H2O2] above 5 mM (see Figure 2D for the MA time trends, and Figure 2B for the corresponding photodegradation rates). The ·OH reactions with carbonate and bicarbonate are more straightforward than in the case of chloride and they lead to the unequivocal formation of CO3·− as additional reactive species [26,29]:

| ·OH + HCO3− → H2O + CO3·− | (8) |

| ·OH + CO32− → OH− + CO3·− | (9) |

A comparison of the MA photodegradation rates in the systems “H2O2 alone” and “H2O2 + Na2CO3” in Figure 2B shows that the rates were lower in the presence of carbonate, coherently with the replacement of ·OH with the less reactive species CO3·−. Moreover, the ratio increased with increasing [H2O2]. A potential explanation for this phenomenon is that H2O2 competes more effectively with MA, for reaction with CO3·−, than for reaction with ·OH. In other words, this hypothesis leads to the assumption that . Considering that = 8 × 105 M−1·s−1 is known from the literature [30], the measurement of by laser flash photolysis is an appropriate test for this hypothesis.

2.3. MA Photodegradation by Persulphate/UV

The UV irradiation of persulphate yields the sulphate radical, SO4·− [31,32,33]. This radical has similar if not higher reduction potential compared to ·OH, but it tends to be preferentially involved in charge-transfer reactions while ·OH often triggers hydrogen-transfer or addition processes in comparable conditions [17,34].

| S2O82− + hν → 2 SO4·− | (10) |

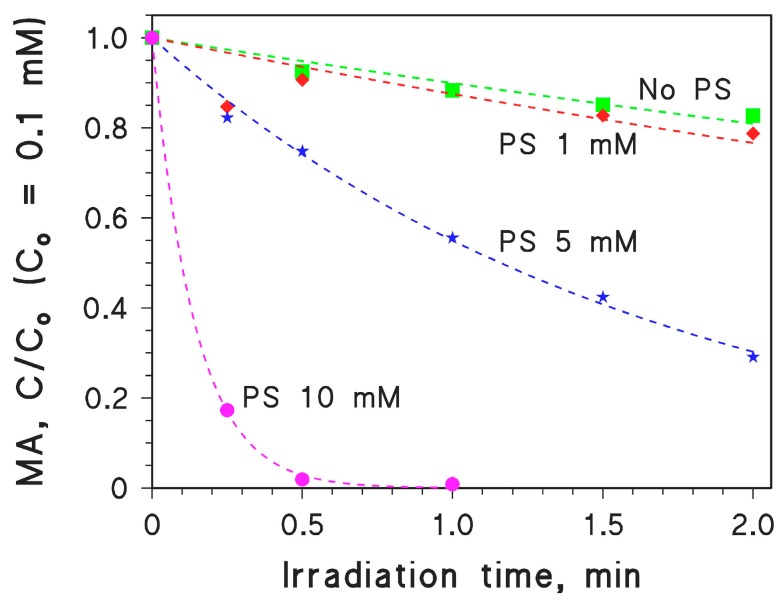

The time trend of 0.1 mM MA upon UVC irradiation in the presence of varying concentration values of sodium persulphate (PS) is reported in Figure 3. The figure shows that PS above 1 mM concentration could considerably accelerate the photodegradation of MA, and that the photodegradation became considerably faster as the PS concentration was higher. Moreover, while there was limited difference between the MA time trends with 5 or 10 mM H2O2, the photodegradation of MA with 10 mM PS was considerably faster compared to 5 mM PS. This result suggests that the reaction between SO4·− and PS interferes with MA photodegradation to a lesser extent than the reaction between ·OH and H2O2.

Figure 3.

Time trend of 0.1 mM MA upon UVC irradiation, alone or in the presence of different concentration values of Na2S2O8 (persulphate, PS). The PS concentration was varied in the range of 0–10 mM.

2.4. Second-Order Reaction Rate Constants of MA with Cl2·−, CO3·− and SO4·−

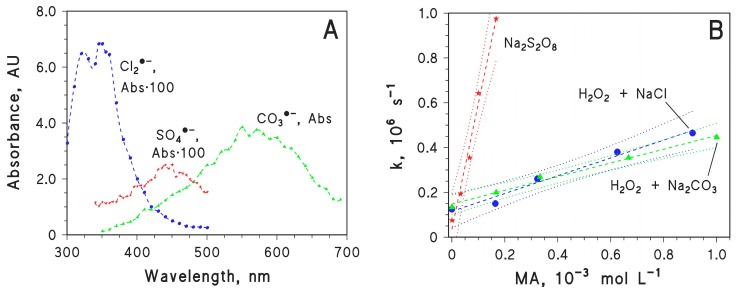

The second-order reaction rate constants between MA and three reactive transient species (Cl2·−, CO3·−, and SO4·−) were measured by means of the laser flash photolysis technique. The radical Cl2·− was produced by laser irradiation of H2O2 + NaCl (0.01 M chloride) at pH 3 by HClO4, under which conditions the equilibria of reactions (4–6) are shifted towards the products and there is a consequent enhancement of the formation of Cl2·− [26,27,28]. As far as the other transient species are concerned, CO3·− was produced by laser irradiation of H2O2 + Na2CO3, and SO4·− was produced by laser irradiation of Na2S2O8. The actual occurrence of these radicals as the main transient species in the laser-irradiated solutions has been demonstrated in previous studies [35,36]. Figure 4A reports the absorption spectra of the studied solutions undergoing laser flash photolysis, obtained just after the laser pulse. Based on these results, in successive experiments the radical Cl2·− was monitored at 350 nm, CO3·− at 550 nm, and SO4·− at 450 nm. Figure 4B reports the trends of the pseudo-first order decay constants k of each transient as a function of the MA concentration. Following the Stern-Volmer approach, the slopes of k vs. [MA] represent the second-order reaction rate constants of the transient species with MA. We obtained = (4.0 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1·s−1 (the error bounds represent the σ-level uncertainty), = (3.1 ± 0.2) × 108 M−1·s−1, and = (5.6 ± 0.4) × 109 M−1·s−1. These values are consistent with the typical reactivity of the three transient species [30].

Figure 4.

(A) Absorption spectra of the radicals CO3·−, Cl2·−, and SO4·− produced by laser flash photolysis of 2.5 mM H2O2 + 0.1 M Na2CO3 (CO3·−), of 2.5 mM H2O2 + 0.01 M NaCl (pH 3, adjusted with HClO4) (Cl2·−), and of 10 mM Na2S2O8 (SO4·−). The absorbance signals were taken soon after the laser pulse. Laser irradiation at 266 nm, 35 mJ·pulse−1; (B) First-order decay constants of the studied radical species (SO4·−, Cl2·−, CO3·−) as a function of MA concentration. The radical species were obtained by laser irradiation of 10 mM Na2S2O8 (SO4·−), of 2.5 mM H2O2 + 0.01 M NaCl at pH 3 (Cl2·−), and of 2.5 mM H2O2 + 0.1 M Na2CO3 (CO3·−). The slopes of the lines give the second-order reaction rate constants between the relevant radicals and MA (Stern-Volmer approach).

The formation of CO3·− and SO4·− upon either laser-based or steady-state irradiation of, respectively, H2O2 + Na2CO3 and Na2S2O8 is rather straightforward [35,36]. In the case of H2O2 + NaCl, the laser irradiation took place at pH 3 to ensure the formation of Cl2·−. In contrast, the corresponding steady irradiation experiments took place at the natural pH, where the involvement of Cl2·− in MA photodegradation is less obvious.

To assess the actual involvement of Cl2·− in the steady irradiation process one can check whether « , as suggested by the steady irradiation results where was directly proportional to (see Figure 2B). Table 2 summarises the second-order reaction rate constants of Cl2·−, CO3·− and ·OH with MA, derived in this study, and those with H2O2 and HO2−, obtained from the literature [26,30].

Table 2.

Second-order reaction rate constants (kX+Y) between the transient species X = Cl2·−, CO3·− or ·OH, and the compound Y = MA, H2O2, or HO2−.

The experimental data of in the presence of H2O2 alone (see Figure 2B) are consistent with ~ 0.01. From this value and the condition « , one gets » 1.4 × 107 M−1·s−1. The laser flash photolysis experiments yielded = (4.0 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1·s−1, in full agreement with the steady irradiation estimate. This means that Cl2·− is a reasonable reactive species for the photodegradation of MA in the presence of H2O2 + Cl− under irradiation in ~neutral solution.

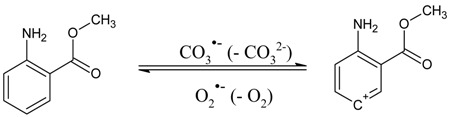

The steady irradiation trend of in the presence of Na2CO3, when interpreted in the framework of a competition kinetics between MA and H2O2 for reaction with CO3·−, gives ~ 0.01. From the literature datum = 8 × 105 M−1·s−1 [30] one gets < 8 × 107 M−1·s−1, which is in stark contrast with the value = (3.1 ± 0.2) × 108 M−1·s−1 obtained by laser flash photolysis. The H2O2 + Na2CO3 solutions had more basic pH (~10) compared to those containing H2O2 + NaCl, thus H2O2 would in part occur as its conjugate base HO2− [37]. However, when considering that = 7.5 × 109 M−1·s−1 [26] and = 3 × 107 M−1·s−1 [30], from the condition one derives < 2 × 107 M−1·s−1, which is again not consistent with the laser flash photolysis results. A more reasonable explanation is that the reactions of HO2− with ·OH and CO3·− are much faster than those of H2O2 (see Table 2), thereby causing a considerable production of HO2·/O2·− (reactions 11, 12; [26,30]). The superoxide radical anion that prevails at the pH conditions of the studied systems [37] is an effective reductant [38], and it could reduce the oxidised MA transients back to the initial compound (see e.g., reaction 13).

| CO3·− + HO2− → HCO3− + O2·− | (11) |

| ·OH + HO2− → H2O + O2·− | (12) |

|

(13) |

The above reactions, ending up in an inhibition of MA photodegradation, might explain the trend of in the presence of carbonate, reported in Figure 2B.

2.5. MA Photodegradation Intermediates

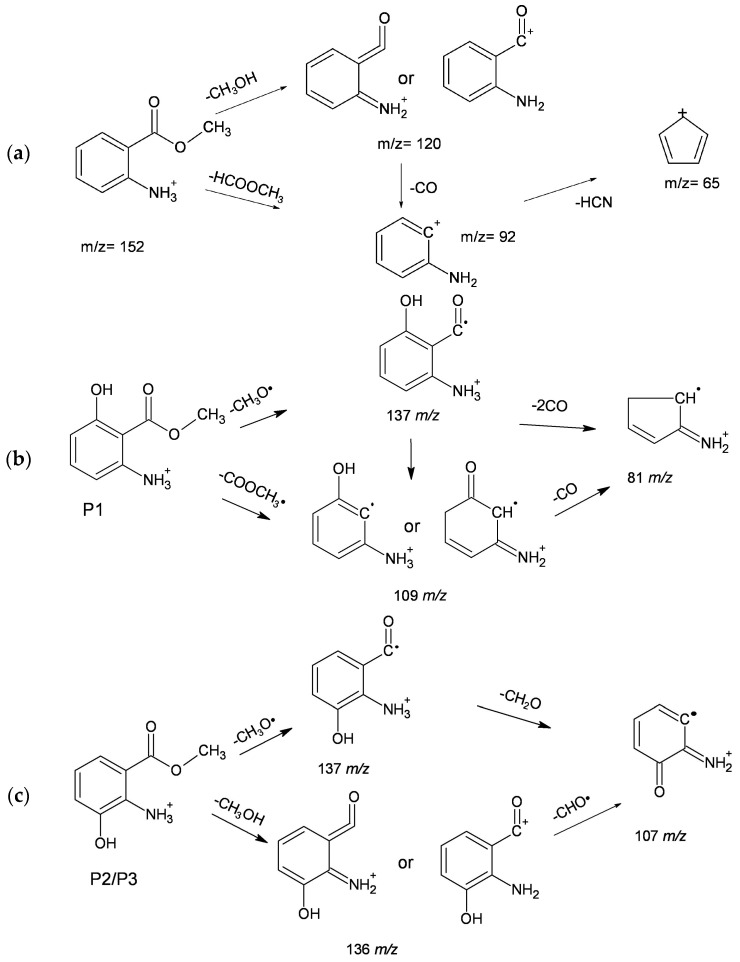

The LC-MS analysis of the MA solutions irradiated in the presence of H2O2, with a conversion percentage of 32%, allowed the detection of MA at the retention time of 12.5 min and of several photodegradation intermediates, namely P1 (10.6 min), P2 (11.0 min), P3 (11.4 min), and P4 (13.1 min). Useful information was initially obtained from the MS spectrum of MA itself. A pattern of MA fragmentation, based on the information obtained in its MS2 spectrum at 20 eV, is shown in Figure 5a. The spectrum shows the formation of a fragment ion with an accurate mass of m/z = 120.0499, which corresponds to an elemental composition of C7H6ON+ (error = −17 ppm) and is formed by the loss of a CH3OH group. This fragmentation is a peculiar behaviour of ortho-substituted esters [39]. Two additional fragment ions are also observed at m/z 92 and 65. The former with an accurate mass of 92.0500 (C6H6N+, error = −1.3 ppm) arises from the loss of HCO2CH3 from the molecular ion, which is a common fragmentation process in the methyl esters of carboxylic acids [40]. The same fragment could also be produced by CO loss from the fragment ion at m/z 120.0499. The fragment with m/z = 65.0391 (C5H5+, error = −3.1 ppm) is obtained from m/z = 92.0500 by loss of HCN.

Figure 5.

Proposed MS fragmentation pathways of: (a) MA; (b) a possible structure of P1; (c) a possible structure of P2/P3.

As far as the intermediates P1, P2, and P3 are concerned, they were characterised by the molecular ion m/z = 168.0655. This is consistent with the elemental composition C8H10O3N+ (error = −3.4 ppm), corresponding to MA monohydroxy derivatives. Remarkably, despite the possibility to hydroxylate MA in four different positions, only three isomers were actually detected with P2 as the major one. The MS2 product ions of these compounds are listed in Table 3, together with the LC retention times of the parent molecules.

Table 3.

Summary of the mass spectrometric data of the detected MA hydroxyderivatives.

| Compound Acronym | LC Retention Time, (min) | MS2 Fragments, m/z (% Relative Abundance) |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 10.6 | 141 (8), 137 (7), 109 (100), 81 (38) |

| P2 | 11.0 | 136 (100), 137 (30), 107 (3) |

| P3 | 11.4 | 136 (100), 137 (25), 107 (25) |

In the case of P1, the most abundant product ion is 109.0515 m/z (C6H7ON+, error = −11.6 ppm), which arises from the loss of CH3COO· and is consistent with the presence of the -OH group in position 4 or 6 with respect to the ester functionality of MA. The fragment at 81.0590 m/z (C5H7N+, error = +14.2 ppm) can be explained with the further loss of another CO group. The formation of the 141.0569 m/z fragment (C7H9O3+, error = +12.3 ppm) can be justified with the loss of HCN, whereas the detachment of a CH3O· radical group would yield the fragment at 137.0470 m/z (C7H7O2N+, error = −5.0 ppm). Unfortunately, no further information is present in the spectrum that allows for the determination of the exact location of the OH group. For explanatory purposes, the fragmentation pathway of the 6-hydroxyderivative of MA is reported in Figure 5b. Remarkably, a totally similar fragmentation that yields fragment ions with the same m/z values could be proposed for the 4-hydroxyderivative.

As far as P2 and P3 are concerned, the most abundant signal occurs at 136.0375 m/z (C7H6O2N+, error = −17.3 ppm) and, in analogy with the fragmentation of MA, it could arise from CH3OH loss. As already seen for P1, one also observes the product ion at 137.0465 m/z. The occurrence of the product ion at 107.0358 m/z (H2CO loss) suggests the presence of an OH group in ortho or para position with respect to the amino group (i.e., in position 3 or 5 with respect to the ester functionality). A possible fragmentation pathway for the 3-hydroxyderivative is shown in Figure 5c, but a fully similar pathway could be proposed for the 5-hydroxyderivative. From the available MS data it was unfortunately not possible to attribute uniquely each isomer to the corresponding signal. However, by assuming that P2 and P3 are the 3- and 5-hydroxyderivatives of MA (irrespective of which is which), one can tentatively conclude that both of them are anyway formed. In contrast, P1 may be either the 4- or the 6-hydroxyderivative. Therefore, one could tentatively assume that hydroxylation takes place in the 3 and 5 positions, plus 4 or 6 (in other words, either the 3-, 4-, and 5- or the 3-, 5-, and 6-hydroxyderivatives would be formed).

In the case of P4, the accurate mass of the molecular ion (m/z = 331.0915) corresponds to the elemental composition C16H15N2O6+, with an error of −4.6 ppm. This indicates the possible presence of an oxidised dimeric structure. Unfortunately, based on the available MS data it was not possible to propose a univocal structure for this compound.

Based on ECOSAR predictions, the MA hydroxyderivatives would show comparable toxicity as the parent molecule [7]. In all the cases the major effects are predicted to be the acute and, most notably, the chronic toxicity towards fish and crustaceans.

3. Methods

3.1. Reagents and Materials

Methyl 2-aminobenzoate (MA, purity grade ≥98%), methanol (gradient grade), HClO4 (70%), NaOH (1.0 M titrated solution), and Na2CO3 (99.9%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). Formic acid (98%), H2O2 (30%), and NaCl (99.5%) were purchased from Fluka (Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). The above chemicals were used as received. Ultra-pure water was prepared with a Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA) Milli-Q apparatus (resistivity ≥ 18.2 MΩ cm, TOC < 2 ppb).

3.2. Irradiation Experiments

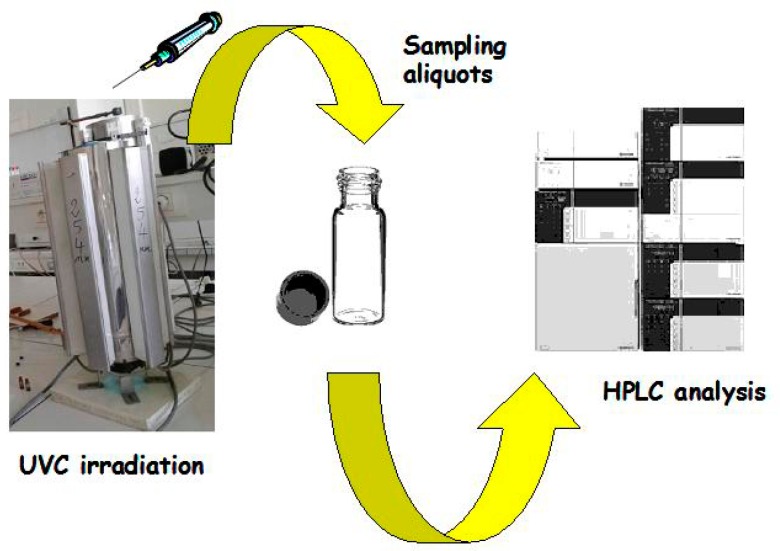

The absorption spectra of the studied compounds (see Figure 1 for MA and H2O2) were taken with a Varian (Palo Alto, CA, USA) Cary 3 UV-vis spectrophotometer, using 1 cm quartz cuvettes. The solution pH was measured with a combined glass electrode connected to a Meterlab pH meter (Hach Lange, Loveland, CO, USA). Solutions containing 0.1 mM MA, and other components where relevant, were inserted inside a quartz tube (100 mL total volume), which was placed in the centre of an irradiation set-up consisting of six TUV Philips (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 15 W lamps with emission maximum at 254 nm. The lamp intensity was 7.6 × 10−9 Einstein cm−2·s−1. The water solutions were magnetically stirred during irradiation. At scheduled irradiation times, 1.5 mL sample aliquots were withdrawn from the tube, placed into HPLC vials, and kept refrigerated until HPLC analysis. The time trend of MA was monitored by means of a high-performance liquid chromatograph interfaced to a photodiode-array detector (HPLC-PDA, model Nexera XR by Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with SIL20-AC autosampler, SIL-20AD pump module for low-pressure gradients, CT 0-10AS column oven (set at 40 °C), reverse-phase column Kinetex RP-C18 packed with Core Shell particles (100 mm × 2.10 mm × 2.6 µm) by Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA), and SPDM 20A photodiode array detector. The isocratic eluent was a A/B = 60/40 mixture of A = (0.5% formic acid in water, pH 2.3) and B = methanol, at a flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1. In these conditions, the MA retention time was 7.3 min. The detection wavelength was set at 218 nm. A schematic of the experimental procedure is reported in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the used experimental procedure.

The time evolution of MA concentration ([MA]) was fitted with the pseudo-first order equation [MA]t = [MA]o , where [MA]t is the concentration of MA at the time t, [MA]o the initial concentration of MA, and kMA the pseudo-first order photodegradation rate constant of MA. The initial rate of MA photodegradation is RMA = kMA [MA]o.

3.3. Identification of Photodegradation Intermediates

The photodegradation intermediates of MA were identified by liquid chromatography interfaced with mass spectrometry (LC-MS). A Waters Alliance (Milford, MA, USA) instrument equipped with an electrospray (ESI) interface (used in ESI+ mode) and a Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Micromass, Manchester, UK) were used. Samples were eluted on a column Phenomenex Kinetex C18 (100 mm × 2.10 mm × 2.6 µm) with a mixture of acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% formic acid in water (B) at 0.2 mL·min−1 flow rate, with the following gradient: start at 5% A, then up to 95% A in 15 min, keep for 10 min, back to 5% A in 1 min, and keep for 5 min (post-run equilibration). The capillary needle voltage was 3 kV and the source temperature 100 °C. The cone voltage was set to 35 V. Data acquisition was carried out with a Micromass MassLynx 4.1 data system. Both MS and MS/MS experiments were carried out by using this chromatographic set-up.

3.4. Laser Flash Photolysis Experiments

The reactivity of the radicals Cl2·−, CO3·−, and SO4·− was studied by means of the nanosecond laser flash photolysis technique. Flash photolysis runs were carried out using the third harmonic (266 nm) of a Quanta Ray GCR 130-01 Nd:YAG laser system instrument, used in a right-angle geometry with respect to the monitoring light beam. The single pulses energy was set to 35 mJ unless otherwise stated. A 3 mL solution volume was placed in a quartz cuvette (path length of 1 cm) and used for a maximum of three consecutive laser shots. The transient absorbance at the pre-selected wavelength was monitored by a detection system consisting of a pulsed xenon lamp (150 W), monochromator, and a photomultiplier (1P28). A spectrometer control unit was used for synchronising the pulsed light source and programmable shutters with the laser output. The signal from the photomultiplier was digitised by a programmable digital oscilloscope (HP54522A). A 32 bits RISC-processor kinetic spectrometer workstation was used to analyse the digitised signal.

3.5. Model Assessment of Toxicity

The potential acute and chronic toxicity of the detected MA intermediates was assessed with the ECOSAR software (US-EPA, Washington DC, USA). ECOSAR uses a quantitative structure-activity relationship approach to predict the toxicity of a molecule of given structure. The relevant endpoints are the acute and chronic toxicity thresholds (LC50, EC50, chronic values ChV) for freshwater fish, daphnid, and algae. The values predicted by ECOSAR are apparently very precise but, as far as accuracy is concerned, a compound can be said to be more toxic than another only when the predicted values differ by at least an order of magnitude [7,8].

4. Conclusions

The H2O2/UV technique as photochemical ·OH source is a potentially effective tool to achieve MA photodegradation, and in fact the addition of hydrogen peroxide considerably accelerated the photodegradation of MA compared to UV irradiation alone. The addition of inorganic anions that act as ·OH scavengers, such as chloride and carbonate, did not necessarily quench MA photodegradation. The reason is the reactivity with MA itself of the generated radical species, i.e., Cl2·− produced from Cl−+·OH and CO3·− produced from CO32−+·OH. In the case of chloride, there was even an acceleration of MA photodegradation at elevated [H2O2], because Cl2·− competes more successfully than ·OH for reaction with MA in the presence of H2O2 (H2O2 behaves as a scavenger of ·OH and, to a lesser extent, of Cl2·− as well). The same effect was not observed with carbonate, possibly because the basic pH caused a considerable production of superoxide (O2·−) upon oxidation of the H2O2 conjugated base, HO2−. The radical O2·− is a well-known reductant that could reduce the partially oxidised MA back to the starting compound. Effective MA photodegradation was also observed with persulphate/UV, probably because of the fast reaction between MA and photogenerated SO4·−, and because of limited scavenging of SO4·− by persulphate itself.

Among the MA photodegradation intermediates detected in the H2O2/UV process, the hydroxyderivatives could be about as toxic as the parent compound. Therefore, decontamination is not yet achieved once MA has disappeared, and the H2O2/UV treatment of MA should at least ensure the photodegradation of the MA hydroxylated derivatives as well. Usually, the photodegradation of both the primary compound and its intermediates takes more time than the photodegradation of the starting compound alone.

Acknowledgments

G.M.L. acknowledges the Erasmus Placement programme for financially supporting her stay in Clermont-Ferrand.

Abbreviations

| kMA | pseudo-first order rate constant of MA photodegradation. |

| kX+Y | second-order reaction rate constant between the species X and the compound Y. |

| RMA | initial photodegradation rate of MA. |

| εY,λ | molar absorption coefficient of the compound Y at the wavelength λ. |

| p°(λ) | incident spectral photon flux density of the used lamp at the wavelength λ. |

| formation rate of the species X in the presence of the compound Y under irradiation. | |

| fraction of radiation absorbed by the compound Y at the wavelength λ, inside the solution S. |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials are available online.

Author Contributions

M.S. conceived the study and corrected the paper. G.M.L. performed the experiments. D.F. interpreted the MS results. D.V. made kinetic calculations and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Sigma-Aldrich. [(accessed on 3 March 2017)]; Available online: http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/aldrich/w268208.

- 2.Fraternale D., Ricci D., Flamini G., Giomaro G. Volatiles profile of red apple from Marche region (Italy) Rec. Nat. Prod. 2011;5:202–207. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolbeer R.A., Clark L., Woronecki P., Seamans T.W. Pen tests of methyl anthranilate as a bird repellent in water; Proceedings of the Eastern Wildlife Damage Control Conference; Ithaca, NY, USA. 6–9 October 1991; pp. 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J.E., Luo W.T., Lorne I.M., Pankow J.F. Candy flavorings in tobacco. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:2250–2252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1403015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.M&U International Methyl Anthranilate Material Safety Data Sheet. [(accessed on 19 December 2016)]; Available online: http://www.mu-intel.com/upload/msds/20141119004116.pdf.

- 6.Clark L., Cummings J., Bird S., Aronov E. Acute toxicity of the bird repellent, methyl anthranilate, to fry of Salmo salar, Oncorhynus mykiss, Ictalurus punctatus and Lepomis macrochirus. Pestic. Sci. 1993;39:313–317. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780390411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayo-Bean K., Moran K., Meylan B., Ranslow P. Methodology Document for the ECOlogical Structure-Activity Relationship Model (ECOSAR) Class Program. US-EPA; Washington DC: 2012. 46 pp [Google Scholar]

- 8.US-EPA, ECOSAR Software (Ecological Structure Activity Relationships Predictive Model) [(accessed on 20 December 2016)]; Available online: https://www.epa.gov/tsca-screening-tools/ecological-structure-activity-relationships-ecosar-predictive-model.

- 9.Avery M.L. Evaluation of methyl anthranilate as a bird repellent in fruit crops; Proceedings of the Fifteenth Vertebrate Pest Conference; Newport Beach, CA, USA. 3–5 March 1992; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorr B., Clark L., Glahn J.F., Mezine I. Evaluation of a methyl anthranilate-based bird repellent: Toxicity to channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus and effect on great blue heron Ardea herodias feeding behavior. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 1998;29:451–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-7345.1998.tb00669.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US-EPA EPI Suite™-Estimation Program Interface. [(accessed on 15 December 2016)]; Available online: https://www.epa.gov/tsca-screening-tools/epi-suitetm-estimation-program-interface.

- 12.Zuccato E., Castiglioni S., Bagnati R., Melis M., Fanelli R. Source, occurrence and fate of antibiotics in the Italian aquatic environment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;179:1042–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.03.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson S.D., Ternes T.A. Water analysis: Emerging contaminants and current issues. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:2813–2848. doi: 10.1021/ac500508t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper W.J., Cramer C.J., Martin N.H., Mezyk S.P., O′Shea K.E., von Sonntag C. Free radical mechanisms for the treatment of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) via advanced oxidation/reductive processes in aqueous solutions. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:1302–1345. doi: 10.1021/cr078024c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brillas E., Sires I., Oturan M.A. Electro-Fenton process and related electrochemical technologies based on Fenton’s reaction chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:6570–6631. doi: 10.1021/cr900136g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pichat P., editor. Photocatalysis and Water Purification. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gligorovski S., Strekowski R., Barbati S., Vione D. Environmental implications of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) Chem. Rev. 2015;115:13051–13092. doi: 10.1021/cr500310b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doré M. Chemistry of Oxidants and Water Treatments. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganiyu S.O., van Hullebusch E.D., Cretin M., Esposito G., Oturan M.A. Coupling of membrane filtration and advanced oxidation processes for removal of pharmaceutical residues: A critical review. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2015;156:891–914. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2015.09.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J.L., Wang S.Z. Removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) from wastewater: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2016;182:620–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rozas O., Vidal C., Baeza C., Jardim W.F., Rossner A., Mansilla H.D. Organic micropollutants (OMPs) in natural waters: Oxidation by UV/H2O2 treatment and toxicity assessment. Water Res. 2016;98:109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minero C., Pellizzari P., Maurino V., Pelizzetti E., Vione D. Enhancement of dye sonochemical degradation by some inorganic anions present in natural waters. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008;77:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avetta P., Pensato A., Minella M., Malandrino M., Maurino V., Minero C., Hanna K., Vione D. Activation of persulfate by irradiated magnetite: Implications for the degradation of phenol under heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:1043–1050. doi: 10.1021/es503741d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matzek L.W., Carter K.E. Activated persulfate for organic chemical degradation: A review. Chemosphere. 2016;151:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braslavsky S.E. Glossary of terms used in photochemistry, 3rd edition (IUPAC Recommendations 2006) Pure Appl. Chem. 2007;79:293–465. doi: 10.1351/pac200779030293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buxton G.V., Greenstock C.L., Helman W.P., Ross A.B. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O−) in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1988;17:1027–1284. doi: 10.1063/1.555805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayson G.G., Parsons B.J., Swallow A.J. Some simple, highly reactive, inorganic chlorine derivatives in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday I. 1973:1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vione D., Maurino V., Minero C., Calza P., Pelizzetti E. Phenol chlorination and photochlorination in the presence of chloride ions in homogeneous aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:5066–5075. doi: 10.1021/es0480567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canonica S., Kohn T., Mac M., Real F.J., Wirz J., Von Gunten U. Photosensitizer method to determine rate constants for the reaction of carbonate radical with organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:9182–9188. doi: 10.1021/es051236b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neta P., Huie R.E., Ross A.B. Rate constants for reactions of inorganic radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1988;17:1027–1284. doi: 10.1063/1.555808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hori H., Yamamoto A., Hayakawa E., Taniyasu S., Yamashita N., Kutsuna S. Efficient decomposition of environmentally persistent perfluorocarboxylic acids by use of persulfate as a photochemical oxidant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:2383–2388. doi: 10.1021/es0484754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Criquet J., Leitner N.K.V. Degradation of acetic acid with sulfate radical generated by persulfate ions photolysis. Chemosphere. 2009;77:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antoniou M.G., de la Cruz A.A., Dionysiou D.D. Degradation of microcystin-LR using sul fate radicals generated through photolysis, thermolysis and e− transfer mechanisms. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2010;96:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2010.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrmann H., Hoffmann D., Schaefer T., Braeuer P., Tilgner A. Tropospheric aqueous-phase free-radical chemistry: Radical sources, spectra, reaction kinetics and prediction tools. ChemPhysChem. 2010;11:3796–3822. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuo Z.H., Cai Z.L., Katsumura Y., Chitose N., Muroya Y. Reinvestigation of the acid-base equilibrium of the (bi)carbonate radical and pH dependence of its reactivity with inorganic reactants. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1999;55:15–23. doi: 10.1016/S0969-806X(98)00308-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Y.L., Bianco A., Brigante M., Dong W.B., de Sainte-Claire P., Hanna K., Mailhot G. Sulfate radical photogeneration using Fe-EDDS: Influence of critical parameters and naturally occurring scavengers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:14343–14349. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martell A.E., Smith R.M., Motekaitis R.J. Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes Database, Version 4.0. NIST; Gaithersburg, MD, USA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bielski B.H.J., Cabelli D.E., Arudi R.L., Ross A.B. Reactivity of HO2•/O2•− radicals in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1985;14:1041–1100. doi: 10.1063/1.555739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merritt C.R.B. In: Mass Spectrometry: Part A. Merritt C. Jr., McEwen C.N., editors. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY, USA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barker J. Mass Spectrometry: Analytical Chemistry by Open Learning. 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons; West Sussex, UK: 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.