Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Does A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase 8 (ADAM8) control extravillous trophoblast (EVT) differentiation and migration in early human placental development?

SUMMARY ANSWER

ADAM8 mRNA preferentially localizes to invasive HLA-G-positive trophoblasts, associates with the acquirement of an EVT phenotype and promotes trophoblast migration through a mechanism requiring β1-integrin.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Placental establishment in the first trimester of pregnancy requires the differentiation of progenitor trophoblasts into invasive EVTs that produce a diverse repertoire of proteases that facilitate matrix remodeling and activation of signaling pathways important in controlling cell migration. While multiple ADAM proteases, including ADAM8, are highly expressed by invasive trophoblasts, the role of ADAM8 in controlling EVT-related processes is unknown.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

First trimester placental villi and decidua (6–12 weeks’ gestation), primary trophoblasts and trophoblastic cell lines (JEG3, JAR, Bewo, HTR8/SVNeo) were used to examine ADAM8 expression, localization and function. All experiments were performed on at least three independent occasions (n = 3).

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Placental villi and primary trophoblasts derived from IRB approved first trimester placental (n = 24) and decidual (n = 4) were used to examine ADAM8 localization and expression by in situ RNAScope hybridization, flow cytometry, quantitative PCR and immunoblot analyses. Primary trophoblasts were differentiated into EVT-like cells by plating on fibronectin and were assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy and immunoblot analysis of keratin-7, vimentin, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), HLA-G and ADAM8. ADAM8 function was examined in primary EVTs and trophoblastic cell lines utilizing siRNA-directed silencing and over-expression strategies. Trophoblast migration was assessed using Transwell chambers, cell–matrix binding was tested using fibronectin-adhesion assays, and ADAM8-β1-integrin interactions were determined by immunofluorescence microscopy, co-immunoprecipitation experiments and function-promoting/inhibiting antibodies.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Within first trimester placental tissues, ADAM8 preferentially localized to HLA-G+ trophoblasts residing within anchoring columns and decidua. Functional experiments in primary trophoblasts and trophoblastic cell lines show that ADAM8 promotes trophoblast migration through a mechanism independent of intrinsic protease activity. We show that ADAM8 localizes to peri-nuclear and cell-membrane actin-rich structures during cell–matrix attachment and promotes trophoblast binding to fibronectin matrix. Moreover, ADAM8 potentiates β1-integrin activation and promotes cell migration through a mechanism dependent on β1-integrin function.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

The primary limitation of this study was the use of in vitro experiments in examining ADAM8 function, as well as the implementation of immortalized trophoblastic cell lines. Histological localization of ADAM8 within placental and decidual tissue sections was limited to mRNA level analysis. Further, patient information corresponding to tissues obtained by elective terminations was not available.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

The novel non-proteolytic pro-migratory role for ADAM8 in controlling trophoblast migration revealed by this study sheds insight into the importance of ADAM8 in EVT biology and placental development.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC-Discovery Grant) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR-Open Operating Grant). There are no conflicts or competing interests.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

NA.

Keywords: A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 8, cell migration, placenta, integrin, trophoblast

Introduction

Early establishment of the human placenta involves coordinated regulation of trophoblast differentiation along two distinct cellular pathways, referred to as the villous and extravillous pathways (Velicky et al., 2016). Trophoblast progenitors committed to the villous pathway terminally differentiate into the multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast of floating villi, a cellular structure that participates in major endocrine and nutrient/waste transfer functions of the placenta (Huppertz, 2011). In contrast, cells differentiating along the extravillous pathway give rise to distinct subtypes of invasive trophoblasts that play central roles in directing uterine blood vessel remodeling, modulating the maternal–fetal immune response and facilitating the physical attachment of the placenta to the uterus (Pijnenborg et al., 2011; Velicky et al., 2016). Invasive trophoblasts, broadly termed extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs), exhibit molecular changes that modify cell–matrix and cell–cell adhesion (Zhou et al., 1997), enhance extracellular matrix degradation/remodeling (DaSilva-Arnold et al., 2015), promote cell migration (Davies et al., 2016) and alter the cell cycle towards a quiescent phenotype (Velicky et al., 2014). Impairments in these EVT-related processes are thought to contribute to placental insufficiency and related pregnancy disorders (Huppertz, 2011). However, relatively little is understood about the cellular and molecular processes that control trophoblast differentiation along the extravillous pathway. Even less is known about the causative nature of EVT-related defects in contributing to pregnancy complications like spontaneous miscarriage, preterm birth and pre-eclampsia.

Trophoblasts residing within anchoring cell columns of placental villi serve as progenitors for invasive interstitial and endovascular EVTs (Haider et al., 2016; De Luca et al., 2017). Within distal regions of anchoring villi, column trophoblasts acquire EVT-like characteristics, including the de novo expression of the MHC class-I molecule, HLA-G, the up-regulation of specific integrin cell–matrix adhesion proteins (i.e. α5 integrin), and production of proteases important in extracellular matrix and cell membrane remodeling (Davies et al., 2016). Global transcriptomic analyses have identified multiple gene families of proteases to be enriched in EVTs (Bilban et al., 2009; Tilburgs et al., 2015). Notably, members of the Zn2+-dependent A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase (ADAM) gene family are highly expressed by invasive trophoblasts (Bilban et al., 2009). Specifically, ADAM8, ADAM12, ADAM19 and ADAM28 mRNA levels are prominent in EVT (Aghababaei and Beristain, 2015), indicating that these proteases play broad roles in EVT-related processes. Indeed in other tissue systems, ADAMs control cell migration/invasion through proteolytic-dependent (Sahin et al., 2004) and -independent (Reiss and Saftig, 2009; Zigrino et al., 2011) mechanisms by regulating growth factor gradients, cell surface receptor function and cell–cell/cell–matrix adhesion.

Recent studies have identified roles for ADAM12 and ADAM28 in EVT biology, where both proteases promote trophoblast column outgrowth and EVT invasion (Aghababaei et al., 2014; Biadasiewicz et al., 2014; De Luca et al., 2017). Notably, the catalytic domain of ADAM12 is necessary for promoting trophoblast invasion (Aghababaei et al., 2014). However, ADAM12 also induces trophoblast spreading through a β1-integrin dependent mechanism (Biadasiewicz et al., 2014), indicating that ADAM-related functions may also include non-proteolytic processes that involve cell–matrix interactions.

Related to ADAM12’s role in controlling cell migration through cell–matrix interactions, ADAM8 promotes endothelial cell migration (Romagnoli et al., 2014) and pancreatic cancer cell invasion (Schlomann et al., 2015) via β1-integrin. As an active membrane-bound metalloprotease, ADAM8 cleaves multiple substrates, including immuno-modulating factors (tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, L-selectin, CD23) (Fourie et al., 2003), cell adhesion molecules (CHL1) (Naus et al., 2004) and proteins important in angiogenesis (Tie-2, Flt-1, VE-cadherin, CD31, EphB4) (Guaiquil et al., 2010). Notably, the distribution of ADAM8 expression is limited within healthy somatic tissues, but is elevated in cancerous and chronically inflamed tissues, indicating that its function may be restricted to pathological processes (Romagnoli et al., 2014). However, the identification of abundant ADAM8 transcripts in invasive trophoblasts suggests that ADAM8 may play an important role in human placental development.

In this study, we set out to characterize ADAM8 localization and function within the fetal–maternal interface. We show that ADAM8 mRNA preferentially localizes to column trophoblasts within anchoring placental villi and to invasive interstitial EVTs within decidual tissue. ADAM8 expression increases in primary trophoblasts differentiating into invasive EVT-like cells, where ADAM8 loss-of and gain-of-function experiments show that ADAM8 promotes trophoblast cell line–matrix adhesion and migration through a mechanism requiring β1-integrin. Together, these findings suggest that ADAM8 plays an important role in early placental development by controlling trophoblast differentiation into the EVT sub-lineage.

Materials and Methods

Tissues

Samples of first trimester (gestational ages ranging from 5 to 12 weeks) placental (N = 24) and decidual tissues (N = 4) were obtained from women (19–35 years of age) providing written informed consent undergoing elective terminations of pregnancy at British Columbia’s Women’s Hospital, Vancouver, Canada. All samples were confirmed to have come from viable pregnancies by ultrasound-measured fetal heartbeat.

Ethical approval

The use of these tissues was approved by the Research Ethics Board on the use of human subjects, University of British Columbia (H13-00 640).

FACS purification of placental cells

Placental villi single cell suspensions were generated from fresh first trimester placental specimens (n = 4) by enzymatic digestion and analyzed by flow cytometry following protocols adapted from Beristain et al. (2015) and Aghababaei et al. (2015). Briefly, placental villi were digested for 1 h at 37°C in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), 750 U/ml collagenase and 250 U/ml hyaluronidase. Organoids obtained after vortexing were subjected to red blood cell lysis in 0.8% (w/v) NH4Cl, further dissociation in 0.25% (w/v) trypsin for 2 min, 5 mg/ml dispase with 0.1 mg/ml DNase I for 2 min, and filtered through a 40 μm mesh to obtain single cells. Contaminating immune cells were removed from the cell admixture by EasySep immuno-magnetic bead purification (all reagents obtained from StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Following magnetic bead exclusion, 2.5 × 106 cells were blocked with Fc receptor antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), and incubated with the following antibodies on ice for 30 min: anti-CD45 (clone 2D1, eBioscience), anti-CD49f-PE-Cy7 (clone GoH3, eBioscience) and anti-HLA-G-PE (clone 87 G, eBioscience). Dead cells were excluded from analysis by staining with 7AAD (eBioscience). The cell surface markers CD49f and HLA-G were used to identify placental trophoblast cell populations, while CD45 was used to identify and exclude contaminating immune cells that were not completely removed by EasySep magnet purification (StemCell Technologies). FACS analysis was performed using FACSDiva (BD, San Diego, CA, USA) and FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, USA). Cell sorting was performed on a FACSAria (BD) into tubes containing ice-cold HBSS/2% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Magnetic bead purification of placental cells

Placental villi single cell suspensions were obtained from first trimester placental villi by enzymatic digestion, density gradient centrifugation and Miltenyi magnetic immuno-bead cell isolation (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Briefly, placental villi were enzymatically digested with 0.125% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; T8003) and 0.1 mg/ml DNAse I (Sigma-Aldrich) over two consecutive 30-min digests to obtain single cell suspensions. After each trypsin digest, supernatant was collected, centrifuged and cell pellets were suspended, washed in DMEM/F12 1:1 containing 10% FBS, and pushed through a 100 μm sieve. Following this, cells were layered onto a 10-layer discontinuous Percoll gradient (10–70%) and centrifuged for 30 min at 1000 g without engagement of the rotor brake, and cell bands residing between 35 and 50% layers were harvested, washed in HBSS, and used to obtain mesenchymal/stromal cells (adherent cells following 30 min of plating onto 30 mm plates) or used to isolate EGFR+ or HLA-G+ cells following the manufacturer’s instructions of Miltenyi MS Column microbead positive cell purification. For microbead cell isolation, 4 × 106 cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with anti-EGFR-PE (R-1, 1:20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) or anti-HLA-G-PE (MEM-G/9, 1:100; ExBio, Vestec, Czech Republic) antibody in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA. Following this, cells were incubated with 20 μl anti-PE microbeads (130-048-801, Miltenyi) per 1 × 107 cells; cells were collected via positive selection using Miltenyi MS MACS separator columns.

Primary trophoblast and cell line culture

Primary trophoblast cultures were propagated from first trimester placental villous tissues (n = 8) using procedures modified from Aghababaei et al. (2014). Briefly, whole placental villi were washed twice in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and following this, villi were enzymatically digested with 0.125% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; T8003) and 0.1 mg/ml DNAse I (Sigma-Aldrich) over two consecutive 30 min digests; after each digest, supernatant was collected, centrifuged and cell pellets were suspended and washed in DMEM/F12 1:1 containing 10% FBS. Following this, cells were layered onto a discontinuous Percoll gradient (10–70%) and centrifuged for 30 min at 1000 g without engagement of the rotor brake, and cell bands residing between 35 and 50% layers were harvested and washed in HBSS. Contaminating immune cells were removed from the cell admixture by EasySep CD45 immuno-magnetic bead purification (StemCell Technologies) where remaining cells were plated onto plastic culture plates for 30 min to remove stromal cells. The 1 × 106 non-adherent cells (following the 30 min pre-culture) were plated onto fibronectin-coated (10 μg/ml) 35 mm culture plates for up to 72 h. The purity of the trophoblast culture was determined by immunostaining for human cytokeratin-7 and vimentin. Only cultures exhibiting >90% immunostaining for cytokeratin-7 were included in this study. On-going trophoblast cultures were maintained in DMEM:F12 1:1 containing 25 mM glucose, 2.5 mM l-glutamine, antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin) and supplemented with 10% FBS (all from Gibco; Grand Island, USA).

JEG3 choriocarcinoma cells (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM media containing 25 mM glucose, 4 mM l-glutamine and sodium pyruvate. JAR choriocarcinoma cells were gifted from Drs S. Lye and C. Dunk (University of Toronto, Canada) and were cultured in RPMI media containing 25 mM glucose, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Bewo choriocarcinoma cells (B30 clone) kindly gifted by Dr J. Strauss III (Virginia Commonwealth University) were maintained in Ham’s F-12K (Kaighn’s) media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The ECT cell line HTR8/SVneo (HTR8) was a generous gift from Dr C.H. Graham (Queen’s University, Canada). HRT8 cells were maintained in RPMI1640 containing 25 mM glucose and 2 mM l-glutamine. All media were supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin).

Immunofluorescence, RNAScope and immunohistochemistry microscopy

Immunofluorescence

Placental villi (6–12 weeks gestation; n = 5) were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Tissues were paraffin embedded and sectioned at 6 μm onto glass slides. Immunofluorescence was performed as described elsewhere (Aghababaei et al., 2014). Briefly, cells or placental tissues underwent antigen retrieval by heating slides in a microwave for 5 × 2 min intervals in a citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Sections were incubated with sodium borohydride for 5 min, RT, followed by Triton X-100 permeabilization for 5 min, RT. Slides were blocked in 5% normal goat serum/0.1% saponin for 1 h, at room temperature (RT), and incubated with combinations of the indicated antibodies overnight, 4°C: Mouse monoclonal KRT7 (1:100, clone RCK105, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, USA); rabbit monoclonal KRT7 (1:75, clone SP52, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, USA); rabbit monoclonal vimentin (1:100, clone D21H3, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA); mouse monoclonal HLA-G (1:100, clone 4H84, Exbio, Vestec, Czech Republic); rabbit monoclonal Ki67 (1:100, clone SP6; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); mouse monoclonal β1-integrin (1:150, clone 12G10, EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA); mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc (1:700, clone 9E10, Sigma Aldrich). Following overnight incubation, sections and coverslips were washed with PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit-488/-586 and goat anti-mouse-488/-568 conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at RT and washed in PBS and mounted using ProLong Gold mounting media containing DAPI (Life Technologies). To detect filamentous-actin, cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 568 Phalloidin (1:60, Thermo Scientific).

Active β1-integrin immunofluorescence intensity measurements were performed using ZenPro2 Image Analysis software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Briefly, subclasses specific to fluorescence channels, intensity thresholds (DAPI channel, EGFP channel, Texas Red channel) and hierarchical conditions were established in JAR cells labeled with anti-active β1-integrin (clone 12G10)/Alexa Fluor-488 secondary, Phalloidin-568 and DAPI. Cell area was defined by Phalloidin-568 signal, and within this area, active β1-integrin mean fluorescence intensity was quantified. For these analyses, a minimum of 124 cells per siRNA condition from three independent experiments (n = 3) were quantified using a 20X Plan-Apochromat/0.8NA objective. For active β1-integrin quantification, cells were identified by phalloidin stain and data were obtained from five randomly selected, non-overlapping fields of view acquired by ZenPro2 automated X/Y axis tiling. For cell imaging experiments, siRNA-transfected JAR cells were plated onto fibronectin-coated 8-well chamber slides for 60 or 120 min prior to fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde.

Immunohistochemistry

Decidua (n = 4) from first trimester pregnancies were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4°C, paraffin imbedded and serially sectioned at 6 μm onto glass slides. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed using sodium citrate (10 mM, pH 6.0) followed by quenching endogenous peroxidases with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at RT. Sections were then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X-100 for 5 min at RT. Serum block was performed with 5% BSA in tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST). Sections were then incubated with mouse monoclonal HLA-G (1:100, clone 4h84, ExBio, Vestec, Czech Republic) diluted in TBST overnight at 4°C. Following overnight incubation, sections were incubated with Envision+ Dual Link Mouse/Rabbit HRP-linked secondary antibody (DAKO) for 1 h at RT. IgG1 isotype controls and secondary antibody-only negative controls were performed to confirm antibody specificity. Staining was developed via 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen (DAB Substrate Kit, Thermo Scientific), counterstained in Modified Harris Hematoxylin Solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and coverslips mounted with Entellan mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA).

RNAScope

RNA in situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope® 2.0 HD Assay-RED (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions (Wang et al., 2012). Briefly, placenta (n = 5) and decidua (n = 4) from first trimester pregnancies were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffin-embedded. Tissue sections were serially sectioned at 6 μm, and following deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was performed using RNAscope® Target Retrieval Reagent (95°C for 15 min) and ACD Protease Plus Reagent (40°C for 30 min). RNAScope probes targeting ADAM8 (Hs-ADAM8-C2; Ref. 512 161-C2) and negative control (Probe-dapB; Ref. 310 043) were incubated on sections for 2 h at 40°C, and following this, the RNAscope signal was amplified over six rounds of ACD AMP 1–6 incubation and application of RED-A and RED-B at a ratio of 1 volume of RED-B to 60 volumes of RED-A for 10 min at RT. Selected samples were counterstained with 50% Hematoxylin I for 2 min at RT and all samples were mounted using Vecta/Mount (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Slides (immunofluorescence, IHC, RNAScope) were imaged with an AxioObserver inverted microscope (Car Zeiss) using 20× LD Plan-Neofluar/0.4NA, 20× Plan-Apochromat/0.8NA or 40× Plan-Apochromat oil/1.4NA objectives (Carl Zeiss). An ApoTome 0.2 structured illumination device (Carl Zeiss) set at full Z-stack mode and five phase images was used for acquiring all immunofluorescence images.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was prepared from FACS-purified cells from placental villi (n = 4) and trophoblastic cell lines (JEG3, Bewo, JAR, HTR8-SVNeo) using TRIzol (cell lines) or TRIzol-LS (FACS-purified cells) (Life Technologies) as described in Perdu et al. (2016). 100–200 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed using a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (QuantaBiosciences Inc.; Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and subjected to SYBR Green (QuantaBiosciences) qPCR (∆∆CT) analysis using an ABI Viia seven Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies) and forward and reverse primer sets for ADAM8 (F: 5′-CCCTTCCCAGTTCCTGTCTA-3′, R: 5′-GGCTCCTTGCTTCCTCTG-3), VIM (vimentin) (F: 5′-AAAGTGTGGCTGCCAAGAACCT-3′, R: 5′-ATTTCACGCATCTGGCGTTCCA-3′), HLA-G (F: 5′-TTGCTGGCCTGGTTGTCCTT-3′, R: 5′-TTGCCACTCAGTCCCACACAG-3′), KRT7 (cytokerain-7) (F: 5′-GGACATCGAGATCGCCACCT-3′, R: 5′-ACCGCCACTGCTACTGCCA-3′) and GAPDH (F: 5′-AGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTGGT-3′, R: 5′-CCCCACTTGATTTTGGAGGGA-3′). All raw data were analyzed using Sequence Detection System software version 2.1 (Life Technologies). The threshold cycle values were used to calculate relative RNA expression levels. Values were normalized to endogenous GAPDH transcripts.

siRNA transfection

Two siRNAs (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) targeting human ADAM8 (hADAM8) mRNA (A8i-1 5′-CGGCACCTGCATGACAACGTA-3′; A8i-2 5′-CTGCGCGAAGCTGCTGACTGA-3′) were employed for transient transfections. ON-TARGETplus non-silencing siRNA#1 (NS; Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA; Cat# D-001 810-01-20) was served as a control. siRNAs (20 nM) were introduced in cells by reverse transfection using Lipofectamine RNAi Max transfection reagent (Life Technologies). Transfected cells were analyzed 24 h post-transfection.

Expression vectors

Full-length and protease-dead (ΔE335Q) human ADAM8 pcDNA3.1/Myc-His and empty pCDNA3.1/Myc-His mammalian expression constructs were kindly gifted to us by Dr GE Sonenshein (Tufts University) (Srinivasan et al., 2014).Two μg/ml of plasmid DNA was transiently transfected into HTR8 trophoblastic cells using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Transfected cell cultures were incubated 48 h post-transfection prior to experimentation. C-terminal HA-tagged CD23b plasmid (#19 136) was obtained from Addgene.

Immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation and zymography

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed in PBS and incubated in RIPA cell extraction buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl) supplemented with 2 mM Na3VO4, 2 mM PMSF and an appropriate dilution of Complete Mini, EDTA-free protease inhibition cocktail tablets (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), for 30 min. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit (Thermo Scientific). For immunoblotting, 30 μg of cell protein lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were probed using antibodies directed against rabbit anti-ADAM8 (polyclonal, 1:1000, LSBio), rabbit β1-integrin (polyclonal, 1:1000, Cell Signaling), mouse anti-HA (clone HA-7, 1:1000, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), mouse anti-Myc (clone Myc.A7, 1:5000, Sigma Aldrich), mouse anti-HLA-G (clone 4H84, 1:2000, ExBio), rabbit anti-EGFR (clone D38B1, 1:1000, Cell Signaling), mouse anti-GAPDH (clone 6C5, 1:10 000, HyTest, Turku, Finland). The blots were stripped and re-probed with an HRP-conjugated monoclonal antibody directed against mouse β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse horseradish-peroxidase conjugated (1:5000, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The intensity of the bands was quantified using Quantity-One software (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunoprecipitation

Whole cell lysate was extracted from JAR cells or primary trophoblasts cultured over 2 h using a 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 5 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4). Endogenous β1-integrin was immunoprecipitated from 200 to 500 μg of whole cell lysate with 0.5 μg mouse anti-β1-integrin antibody (clone P5D2, Abcam); prior to immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were pre-cleared with protein A/G agarose beads overnight at 4°C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Following protein A/G bead IgG pulldown, β1-integrin immunoprecipitates were subjected to gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting, probing against rabbit anti-ADAM8 (1:1000, LSBio, Seattle, WA, USA), rabbit anti-α5-integrin (polyclonal, 1:1000, Cell Signaling) and rabbit anti-β1-integrin (polyclonal, 1:1000, Cell Signaling).

Zymography

Following 24 h of culture in complete media after transfection, ADAM8-silenced JAR cells and ectopically expressing ADAM8 HTR8-SVNeo cells were cultured in serum free media for 48 h. At this point conditioned media (CM) was collected and clarified by centrifugation, concentrated × 10 using Amicon Ultra 3 K centrifugal filters (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), and protein concentration was normalized to 10 μg/μl. The 100 μg of each sample was run on a non-reducing 7.5% acrylamide gel containing 400 μg/ml gelatin, after which gels were incubated with incubation buffer (1% Triton-X 100, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2) for 24 h at 37°C. Following this, gels were stained with 0.5% Coomassie Blue, destained, and imaged using a Biorad Gel Doc XR+ System.

Transwell migration assays

Cell motility assays were performed using uncoated (migration); fibronectin-coated (10 μg/ml, Sigma); and Matrigel-coated (growth factor reduced, BD; diluted 1:1 DMEM/F12) Transwells fitted with Millipore membranes (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA; 6.5 mm filters, 12 μm pore size) as described (Aghababaei et al., 2014). Briefly, primary trophoblasts, JAR and HTR8 cells suspended at 2 × 104 cells/200 μl in DMEM/F12, DMEM or RPMI1640 media with 1% BSA were plated in the upper chambers and cultured for the indicated times. Lower chambers contained 500 μl of DMEM or DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells from the upper surface of the Millipore membrane were removed by gentle swabbing, and transmigrated cells attached to the membrane were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with eosin. The filters were rinsed with water, excised from the Transwells, and mounted upside down onto glass slides. Cell invasion was determined by counting the number of DAPI-stained nuclei in 10 randomly selected, non-overlapping fields using a ×10 Plan-Apochromat/0.80NA objective (Carl Zeiss) and quantified using ZenPro2 software (Carl Zeiss). Cell invasion was tested in duplicate wells, on three independent occasions. For cell migration experiments examining β1-integrin function, activating 12G10 (10 μg/ml) or inhibitory P5D2 (10 μg/ml) were added to cell culture media.

Cell adhesion assay

JAR and HTR8 (2 × 103) cells in 100 μl of serum-free media supplemented with 0.1% BSA were added to fibronectin-coated wells in a 96-well plate. After 20 or 120 min, the wells were washed two times with serum free media to remove the non-adherent cells. Adherent cells were left to recover in media supplemented with 10% FBS for 3 h. MTT (0.5 mg/ml) was added to the cells. After 2 h incubation, formazan was dissolved in 100 μl of DMSO and measured the optical density at 560 nm and subtracted background at 670 nm.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded in triplicate at 1 × 103 cells/well into opaque 96-well microplates containing 100 μl of DMEM or RPMI with 5% FBS. Cells were cultured for 0, 24, 48 or 72 h, after which cell viability/number was measured using the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega; Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was recorded using a FLUOstar Optima plate reader (BMG LabTech; Ortenberg, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Flow cytometry and microscopy image data are reported as median values and inter-quartile ranges (IQR). Quantitative PCR gene expression, cell adhesion, proliferation and immunoblot densitometry data are presented as mean values ± SD. All calculations were carried out using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA). For single comparisons, Mann–Whitney non-parametric unpaired two-tailed t-tests were performed. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis analyses, followed by Dunn’s post-test were performed. The differences were accepted as significant at P < 0.05.

Results

ADAM8 is expressed by multiple trophoblast cell types within the fetal–maternal interface and preferentially localizes to HLA-G+ cells

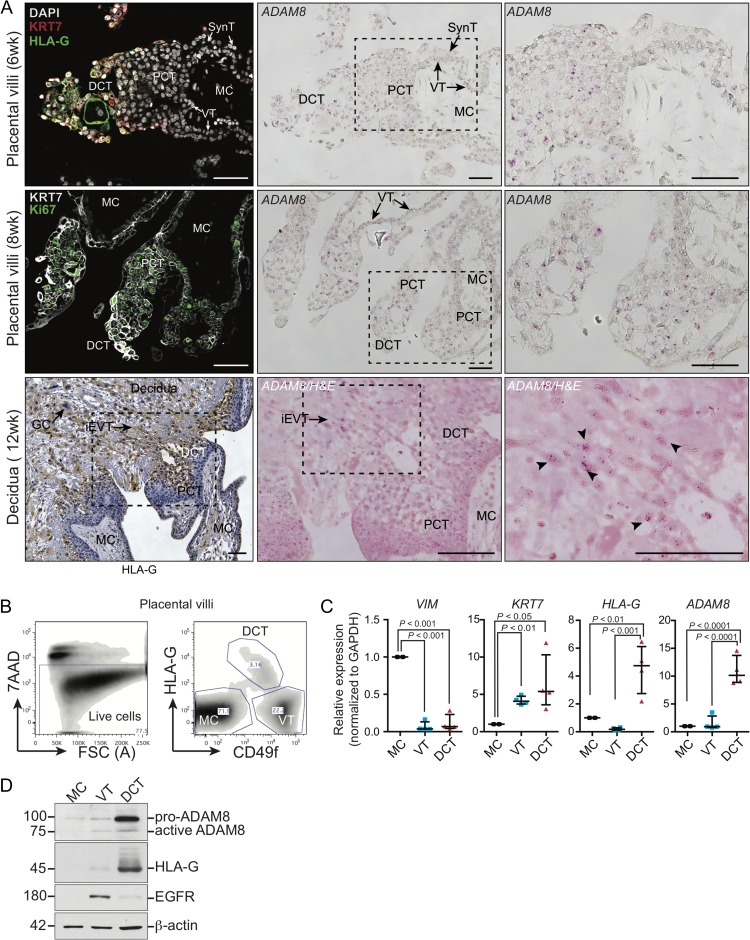

To examine ADAM8’s localization within the fetal–maternal interface, in situ RNAscope labeling of endogenous ADAM8 mRNA in first trimester placental (6–11 weeks’ gestation) and decidual tissues (10–12 weeks’ gestation) were performed. RNAscope is a new technique that enables molecular visualization of RNA signal (Wang et al., 2012), and was used as a substitute for traditional immunohistochemistry analysis as we were unable to optimize ADAM8 antibody labeling on frozen or formalin-fixed placental specimens (three commercial antibodies were tested). Serially sectioned tissues immunostained with antibodies targeting keratin-7 and/or HLA-G facilitated trophoblast subtype identification within placenta (i.e. villous trophoblast, syncytiotrophoblast, proximal and distal column trophoblast (DCT)) and decidua (interstitial EVT). ADAM8 mRNA localized to multiple trophoblast subtypes within placental villi (Fig. 1A). Specifically, within floating placental villi, ADAM8 signal was detected in villous trophoblasts underlying anchoring columns, but was otherwise absent in the majority of villous trophoblasts, whereas moderate ADAM8 signal was observed within the syncytiotrophoblast (Supplementary Fig. S1). Within anchoring villi, ADAM8 signal was strong and localized to both proximal HLA-G−/Ki67+ and distal HLA-G+/Ki67− column trophoblasts; low-undetectable ADAM8 signal was observed within the mesenchymal core of placental villi (Fig. 1A). In samples labeled with the negative control probe, no signal was detected in placental villi (Supplemental Fig. S1). Within the decidua, ADAM8 signal localized to anchoring EVT columns and to HLA-G+ interstitial EVT, including multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

ADAM8 preferentially localizes to anchoring columns of placental villi. (A) Representative immunofluorescence, immunohistochemistry and RNAScope microscopy images of serially sectioned first trimester placental villi (6–11 weeks gestation; n = 5) and decidua (10–12 weeks gestation; n = 4) showing ADAM8 mRNA transcript localization (pink punctate signal) within trophoblast subtypes. Proximal and distal column, as well as interstitial EVT subtypes of trophoblasts are identified by immunostaining of cytokeratin (KRT7) and HLA-G. ‘PCT’ indicates proximal column trophoblast; ‘DCT’ indicates distal column trophoblast; ‘VT’ indicates villous trophoblast; ‘SynT’ indicates syncytiotrophoblast; ‘MC’ indicates placenta mesenchymal core; ‘iEVT’ indicates interstitial extravillous trophoblast; ‘GC’ indicates trophoblast giant cell. The perforated white box indicates enlarged inset image. Black arrowheads denote ADAM8 signal. Bars = 100 μm. (B) Fluorescence activated cell-sorting (FACS) plots demonstrate the trophoblast isolation strategy used to purify mesencymal core cells (MC), distal column trophoblasts (DCT) and villous/proximal column trophoblasts (VT). Live cells, depleted of CD31+ (endothelial) and CD45+ (immune) cells using immuno-magnetic beads, were positively gated by 7AAD exclusion. Cells were further segregated by excluding CD45+ immune cells and by cell surface labeling of HLA-G and CD49f. Cell subtype proportions are indicated within each gated population (percent of cells within FACS plot). (C) ADAM8 mRNA levels in FACS-purified MCs, VTs and DCTs. Trophoblast subtype purity was assessed by qPCR analysis targeting the pan-trophoblast marker KRT7, the EVT-marker HLA-G and the mesenchymal lineage marker VIM. GAPDH was used for normalization. Results are presented as mean ± SD in bar graphs from four distinct placental villi specimens (n = 4); results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (D) Immunoblot showing protein levels of pro- and active-ADAM8, HLA-G, and EGFR in MC, VT and DCT isolated from placental villi using immuno-magnetic beads. Molecular weights (kDa) are shown to the left and β-actin indicates loading control.

To confirm ADAM8’s preferential expression in column trophoblasts, total RNA from flow cytometry sorted villous (VT) and proximal column (PCT) and DCT was subjected to ADAM8 qPCR analysis (Fig. 1B) (Aghababaei et al., 2015; De Luca et al., 2017). Cell sorting of trophoblast subpopulations was based on cell surface expression of CD49f and HLA-G, and trophoblast subtype purity was confirmed by assessment of lineage specific KRT7 (epithelial/trophoblast) and VIM (mesemchymal) markers, as well as DCT-specific HLA-G expression (Fig. 1C). Consistent with our in situ RNA labeling findings, ADAM8 mRNA levels were markedly higher in HLA-G+ DCTs compared to VTs/PCTs or mesenchymal cells (Fig. 1C). To assess if ADAM8 protein levels within these distinct placental cell populations correlated with mRNA data, we probed for ADAM8 in protein lysates obtained from epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)+ and HLA-G+ cells from first trimester placental villi purified using magnetic microbeads; EGFR is a specific villous trophoblast marker and identifies subsets similar/analogous to HLA-G−/CD49fhi populations. Immunoblotting confirmed that ADAM8 protein is prevalent in HLA-G+ trophoblasts, while EGFR-/HLA-G− mesenchymal/stromal cells and EGFR+ villous trophoblasts express little/no ADAM8 (Fig. 1D). Together, these findings show that ADAM8 is expressed by multiple trophoblast cell types and is particularly elevated in HLA-G+ trophoblasts of anchoring columns, indicating that ADAM8 may play a role in aspects of EVT differentiation and function.

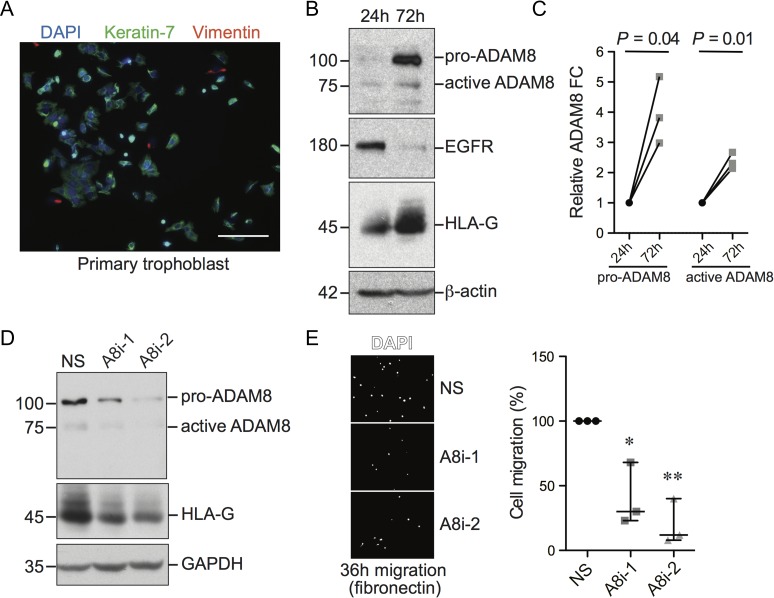

ADAM8 expression increases during EVT differentiation and promotes trophoblast migration

To examine ADAM8 expression dynamics during the differentiation of cultured trophoblasts into EVT-like cells, primary trophoblasts from first trimester placenta were seeded onto fibronectin-coated plates and cultured for 24 and 72 h; primary trophoblasts seeded onto fibronectin spontaneously differentiate into HLA-G-expressing EVT-like cells (Velicky et al., 2014). Probing cells for keratin-7 and vimentin and assessment by immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that the purity of trophoblast cultures exceeded 90% with minimal fibroblast contamination (Fig. 2A). Following 72 h of culture, immunoblot analysis showed that levels of HLA-G increased while levels of EGFR (a villous trophoblast marker) decreased, indicative of successful EVT differentiation (Fig. 2B). Notably, EVT differentiation correlated with an increase in both pro- and active-forms of ADAM8 protein (∼100 and 75 kDa products), further supporting that ADAM8 expression associates with the EVT phenotype (Fig. 2B and C).

Figure 2.

ADAM8 increases during extravillous trophoblast (EVT) differentiation and promotes cell migration. (A) Representative immunofluorescence microscopy image of primary trophoblasts 24 h post-seeding onto fibronectin-coated plate. Cells were immunostained with antibodies directed against keratin-7 (green), vimentin (red) and DAPI (blue). Bar = 100 μm. (B) Immunoblot showing protein levels of pro- and active-ADAM8, EGFR and HLA-G in whole cell lysates derived from primary trophoblasts cultured over 72 h on fibronectin-coated plates. Molecular weights (kDa) are shown to the left and β-actin indicates loading control. (C) Graph depicts pair-wise comparisons of pro- and active-ADAM8 protein fold-change in primary trophoblasts at 72 h of culture compared to levels at 24 h (n = 3). Shown is the P value (paired t test, two-tailed). (D) Representative immunoblot showing protein levels of pro- and active-ADAM8 and HLA-G in primary trophoblasts transfected with control non-silencing siRNA (NS) or siRNA targeting ADAM8 (A8i-1, A8i-2) following 72 h of culture (n = 3). Molecular weights (kDa) are shown to the left and GAPDH indicates loading control. (E) Representative Transwell migration images of primary trophoblasts transfected with control or ADAM8-silencing siRNA stained with DAPI (white) following 36 h of culture (n = 3 experiments). Graph to the right shows quantification of trophoblast migration as a proportion normalized to NS control. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test).

We next set out to investigate if ADAM8 expression affects the migratory capacity of EVT. To do this, siRNA-directed silencing of ADAM8 in primary trophoblasts seeded onto fibronectin-coated Transwells was performed (Fig. 2D and E). Two ADAM8-targeting siRNAs (A8i-1, A8i-2) and one non-silencing control siRNA (NS) were used in these experiments, and ADAM8 knockdown efficiency was assessed 72 h post-transfection by immunoblotting (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, ADAM8 silencing resulted in moderately lower levels of HLA-G, suggesting that ADAM8 may play roles in controlling EVT differentiation (Fig. 2D). Further, ADAM8 knockdown led to a decrease in EVT migration (Fig. 2E). These results provide evidence that ADAM8 expression is regulated during EVT differentiation and that ADAM8 functions to promote a pro-migratory phenotype.

ADAM8-controlled migration does not require intrinsic proteolytic activity

To examine the role of ADAM8 in more depth, we resorted to testing ADAM8 function in trophoblastic cell lines that serve as models for specific trophoblast-related processes (i.e. proliferation, invasion, fusion, endocrine function). As a first step, ADAM8 mRNA and protein levels were examined by qPCR and immunoblot analyses in four distinct cell lines: JEG3, JAR, Bewo and HTR8. ADAM8 expression was shown to be highest (both mRNA and protein) in JEG3 cells, with moderate mRNA and high protein levels also detected in JAR and Bewo cells (Fig. 3A and B). Notably, these trophoblastic cell lines expressed both the full-length pro- and the truncated active-form of ADAM8 (Fig. 3B). In contrast, ADAM8 levels (mRNA and protein) were undetectable in HTR8 cells (Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

ADAM8 promotes trophoblastic cell migration independent of its proteolytic activity. (A) qPCR analysis of ADAM8 in JEG3, JAR, Bewo and HTR8 trophoblastic cell lines (n = 3 for each). Gene expression was normalized to endogenous GAPDH. (B) Immunoblot showing protein levels of pro- and active-ADAM8 in JEG3, JAR, Bewo and HTR8 cell lines. Molecular weights (kDa) are shown to the left and GAPDH indicates loading control. Immunoblots showing protein levels of pro- and active-ADAM8 and CD23-HA in whole cell lysates (WCL) and conditioned media (CM) of (C) JAR cells transfected with control (NS) and ADAM8-silencing (A8i-1, A8i-2) siRNA and (D) HTR8 cells transfected with empty (EV), ADAM8 full-length (A8) and protease-dead ADAM8 (A8∆EQ) pCDNA3.1 expression constructs. Molecular weights (kDa) are shown to the left and β-actin indicates loading control. (−) Indicates non-transfected control cells. Graphs show quantification of Transwell cell migration in (E) JAR cells transfected with control (NS) and ADAM8-silencing (A8i-1, A8i-2) siRNA (n = 3 or n = 4 per condition) and (F) HTR8 cells transfected with empty (EV), ADAM8 full-length (A8) and protease-dead ADAM8 (A8∆EQ) (n = 3 or n = 4 per condition). Transwells were either uncoated or coated with fibronectin or Matrigel. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001; One-way ANOVA (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). (G) Gelatin zymography image showing pro- and active-MMP2/MMP9 in JAR and HTR8 cells transfected with control/ADAM8 siRNA or ectopic control/ADAM8 expression constructs. Immunoblot of GAPDH indicates protein loading in each well. Molecular weights (kDa) are shown to the left. Line graphs depict cell proliferation (H) in JAR cells transfected with control (NS) and ADAM8-silencing siRNA (A8i-1, A8i-2) over 72 h or (I) HTR8/SVneo cells transfected with empty (EV), ADAM8 full-length (A8) or protease-dead ADAM8 (A8∆EQ) over 48 h (n = 3 for each cell line). ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001; one-way ANOVA (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test).

To further dissect ADAM8 function, JAR and HTR8 cell lines were selected for endogenous silencing (JAR) and ectopic over-expression (HTR8) experiments. The JAR choriocarcinoma cell line is moderately migratory, while the SV-transformed HTR8 cell line is highly invasive; both cell lines are commonly used to study trophoblast related processes. To verify that endogenous, as well as ectopic ADAM8 is proteolytically active, we examined ADAM8’s ability to cleave cell surface CD23, a previously characterized ADAM8 substrate (Fourie et al., 2003). In ADAM8-silenced JAR cells ectopically expressing HA-tagged CD23, soluble CD23 levels in CM were reduced compared to NS-transfected controls (Fig. 3C). Co-expression of full-length ADAM8 (A8) and CD23-HA in HTR8 cells clearly revealed a soluble 25 kDa CD23 product in CM; expression of protease-dead ADAM8 (A8∆EQ) and an empty control vector did not lead to CD23 cleavage (Fig. 3D). Together, these experiments establish that both endogenous and ectopic ADAM8 is proteolytically active, and that our loss-of and gain-of-function systems in JAR and HTR8 cells are intact.

To reaffirm our earlier finding that ADAM8 promotes trophoblast migration, ADAM8-silenced JAR cells were subjected to Transwell migration (uncoated, fibronectin-coated) and invasion (Matrigel-coated) assays. On all three matrices, ADAM8 knockdown impaired cell migration and invasion by ~40%, although A8i-2 siRNA was more effective at blocking migration than A8i-1 siRNA (Fig. 3E). In HTR8 cells, over-expression of ADAM8 led to a 3-fold increase in cell migration and invasion through uncoated, fibronectin- and Matrigel-coated Transwells (Fig. 3F). To our surprise, protease-dead ADAM8 also promoted HTR8 migration and invasion, suggesting that ADAM8 promotes trophoblast motility through a mechanism independent of its proteolytic function (Fig. 3F). To investigate this further, we tested if ADAM8 manipulation altered intrinsic gelatinase activity (MMP2, MMP9) in JAR and HTR8 cells, as MMP proteolytic activity is known to control trophoblast invasion (Onogi et al., 2011). While gelatinase zymography showed that JAR cells express high levels of pro- and active-forms of MMP2 (and negligible amounts of MMP9), ADAM8 silencing did not affect baseline levels of MMP2 expression or activity (Fig. 3G). In HTR8 cells that predominately expressed only the pro-forms of MMP2 and MMP9, ectopic expression of proteolytically active and inactive ADAM8 did not affect baseline MMP levels (Fig. 3G). These findings suggest that ADAM8 controls trophoblast migration/invasion through MMP-independent mechanisms.

We next investigated if ADAM8’s effect on trophoblast migration could in part be explained through actions on cell viability. Both loss-of and gain-of ADAM8 function did not conclusively alter cell viability/expansion in either cell line; while A8i-1 siRNA had no effect on JAR viability, at 48 and 72 h, A8i-2 siRNA impaired cell viability (Fig. 3H). Ectopic expression of either active or protease-dead ADAM8 did not affect HTR8 expansion (Fig. 3I). Together, these findings indicate that ADAM8 promotes a migratory and invasive phenotype in trophoblasts that does not require intrinsic protease activity.

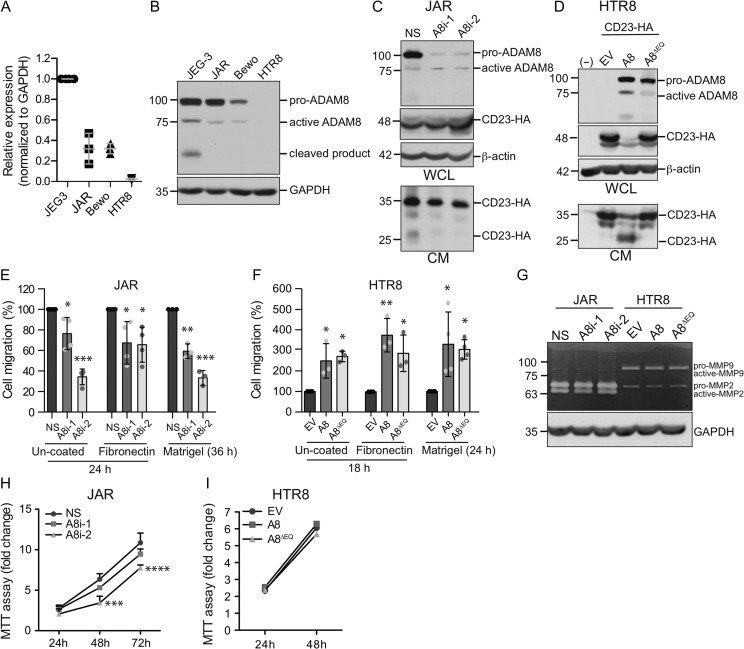

ADAM8 localizes to actin-rich structures and promotes cell attachment to fibronectin matrix

To help elucidate the mechanism by which ADAM8 promotes trophoblast migration, we next examined the intracellular localization of ectopic ADAM8 within transiently transfected HTR8 cells. Because we were unable to demonstrate specific ADAM8 immunofluorescence labeling (three commercial ADAM8 antibodies were tested), ectopic ADAM8 visualization was facilitated by probing against an in-frame Myc epitope tag. To visualize localization of ADAM8 during early and late cell–matrix binding and spreading, cells were fixed at 20 and 120 min post-seeding on fibronectin. At 20 min, cells expressing full-length and protease-dead ADAM8 showed distinct punctate-peri-nuclear localization of ADAM8 (Fig. 4A). Although less strong, ADAM8 signal was also evident peripherally at the cell membrane (Fig. 4A). In both cell membrane and peri-nuclear compartments, ADAM8 signal overlapped with filamentous actin (Fig. 4A). At 120 min post-seeding, the punctate and membrane-associated ADAM8 signal was lost, but was now diffuse and cytoplasmic, and did not appear co-localize with the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

ADAM8 transiently localizes to actin-rich structures during cell attachment and promotes cell adhesion to fibronectin matrix. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images (from n = 4 experiments) of transiently transfected HTR8 cells probed with antibody directed against Myc-tag epitope (white or green). Filamentous actin is labeled with phalloidin (white or red) and nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Cells were transfected with full-length pCDNA3.1-ADAM8 (ADAM8-Myc) or protease-dead pCDNA3.1-ADAM8∆EQ (ADAM8∆EQ-Myc) expression constructs and seeded on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 20 and 120 min. Perforated white box shows magnified region. Bars = 20 μm. Bar graphs show relative proportions of cells adhering to fibronectin matrix in (B) HTR8 cells transiently transfected with control empty vector (EV), full-length ADAM8 (A8), and protease-dead ADAM8 (A8∆EQ) or in (C) JAR cells transfected with control (NS) and ADAM8 silencing (A8i-1, A8i-2) siRNA following 20 or 120 min of culture (n = 3 per condition). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test).

Cell migration is in part controlled by the ability of a cell to bind to its underlying substratum to generate tractile force (Zaman et al., 2006; Nordenfelt et al., 2016). To investigate if ADAM8 peri-nuclear and cell membrane dynamics alters the ability of cells to adhere to fibronectin matrix, HTR8 cells ectopically expressing ADAM8 were subjected to cell–matrix adhesion assays. Compared to control cells transfected with an empty pCDNA3.1 vector, over-expression of full-length and protease-dead ADAM8 enhanced HTR8 binding to fibronectin 20 min post-seeding (Fig. 4B). By 120 min, no difference in cell–matrix adhesion was observed between ADAM8-expressing and non-expressing HTR8 cells (Fig. 4B). To determine if this effect is conserved in other trophoblastic cell types, we tested how loss-of endogenous ADAM8 affects JAR cell-fibronectin adhesion. Consistent with our over-expression model, ADAM8-silencing led to impaired binding of JAR cells to fibronectin at 20 min post-seeding. However, by 120 min, both control and ADAM8-silenced cell adherence was comparable (Fig. 4C). Together, these findings indicate that ADAM8 induces trophoblast migration, in part by initiating/promoting cell–matrix adhesion.

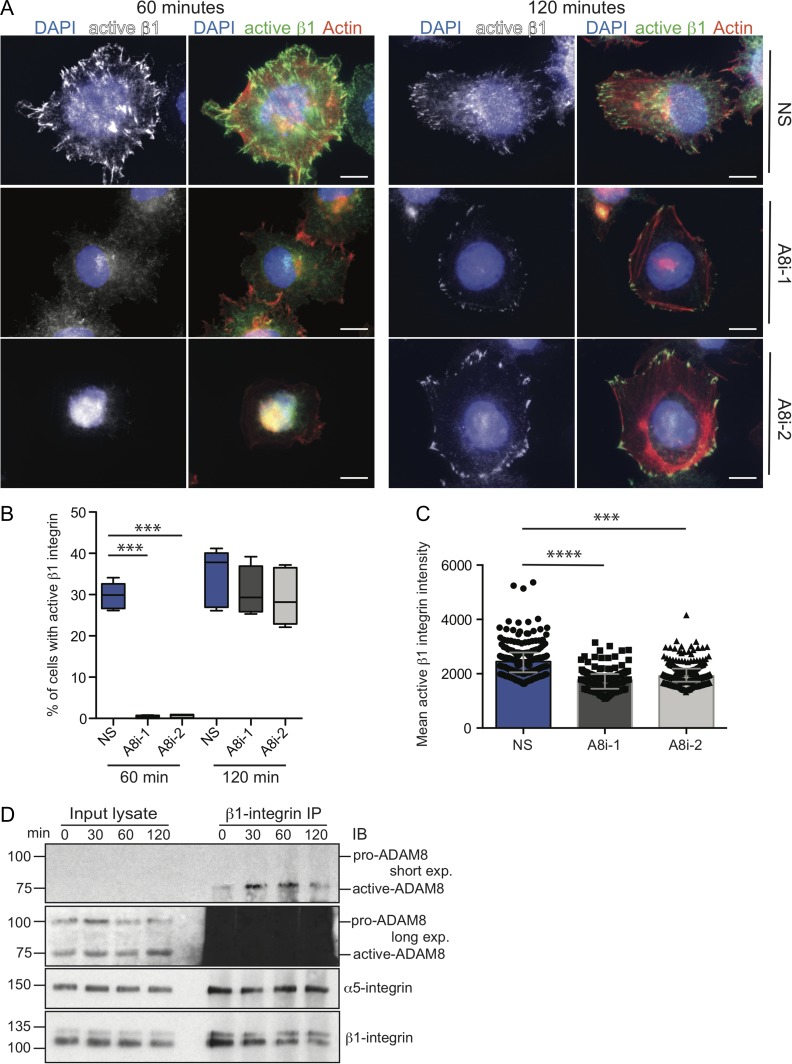

Loss-of ADAM8 blunts β1-integrin activation during cell–matrix attachment

ADAM8’s ability to promote trophoblast attachment to fibronectin suggests that ADAM8 may be regulating integrin-dependent cell–matrix binding, and in particular β1-integrin dependent adhesion since this β integrin subunit preferentially facilitates binding to fibronectin (Takada et al., 1992). To investigate this more closely, β1-integrin localization and activity was assessed in control and ADAM8-silenced JAR cells seeded on fibronectin. Following 60 and 120 min post-seeding, β1-integrin localization was visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy by probing with an antibody (clone 12G10) that recognizes the active conformation of fibronectin-bound β1-integrin (Fig. 5A). We initially examined JAR cells fixed at 20 min post-seeding (the time point used in HTR8 adhesion assays), however at this earlier time point, JAR cells had not adequately spread on fibronectin to facilitate immunofluorescence imaging; 60 min was determined to be adequate for visualization of JAR spreading. At 60 min, ∼30% of control NS-transfected cells showed an active β1-integrin signal that was highly punctate and localized to protruding cellular extensions (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, ADAM8 silencing led to a decrease in active β1-integrin signal intensity (Fig. 5A and C), characterized by diminished punctate β1-integrin localization within extending cellular processes (punctate signal was observed in <1% of cells) (Fig. 5B). Notably, ADAM8-silenced JAR cells appeared more rounded and less spread out than control cells (Fig. 5A). Indeed, mean fluorescence intensity of active β1-integrin signal was decreased in ADAM8-silenced JAR cells (Fig. 5C). By 120 min, the punctate active β1-integrin signal was detectable in both control and ADAM8 knock-down JAR cells, however this signal in ADAM8-silenced cells was limited to the membrane periphery of cell protrusions as compared to the more robust pattern seen in control NS-transfected cells (Fig. 5A and B). Importantly, in control and ADAM8 knockdown cells 120 min post-seeding, cells appeared equally attached and spread on fibronectin (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

ADAM8 potentiates trophoblast–matrix attachment by engaging β1-integrin-dependent cell spreading. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images (from n = 3 experiments) of JAR trophoblastic cells transfected with control (NS) or ADAM8-silencing (A8i-1, A8i-2) siRNA probed with antibody directed against active β1-integrin (clone 12G10; white or green) following 60 or 120 min post-seeding onto fibronectin matrix. Filamentous actin is labeled with phalloidin (white or red) and nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Bars = 20 μm. (B) Box-plots show the proportion of control and ADAM8 siRNA transfected JAR cells harboring the punctate active β1-integrin signal. ***P ≤ 0.001; One-way ANOVA (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). (C) Bar graph shows mean cell intensity of active β1-integrin fluorescence signal in control (NS) and ADAM8-silenced (A8i-1, A8i-2) JAR cells following 60 min of seeding onto fibronectin matrix. ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001; one-way ANOVA (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test). (D) Representative immunoblots (IB) showing co-immunoprecipitation of active β1-integrin (clone 12G10) with active-ADAM8 in JAR cells seeded onto fibronectin over 120 min (0–120 min). Whole cell protein lysates (input lysate) or β1-integrin immunoprecipitates (β1-integrin IP) were probed with antibodies targeting ADAM8, α5-integrin and β1-integrin (clone P5D2). Shown are short (short exp.) and long (long exp.) exposures for ADAM8 signal. Molecular weights (kDa) are shown to the left.

Our imaging results suggest that ADAM8 transiently enhances β1-integrin-directed trophoblast adhesion to fibronectin. To examine if ADAM8 interacts with β1-integrin during the initial and later stages of cell–matrix attachment, β1-integrin was immunoprecipitated (IP) from parental JAR cells adhering to fibronectin over 120 min (0–120 min) where ADAM8 interaction was assessed via immunoblot analysis (Fig. 5D). As a positive control for protein known to co-IP with β1-integrin, α5-integrin was probed for and was shown to pull down with β1-integrin as expected (Fig. 5D). Notably, proteolytically processed ADAM8 (∼75 kDa), but not the pro-form of ADAM8, co-IP’d with β1-integrin, with levels peaking at 30 and 60 min following fibronectin plating (Fig. 5D). To examine if ADAM8 also interacts with β1-integrin in primary trophoblasts, ADAM8 protein was probed in β1-integrin immunoprecipitates derived from primary trophoblasts seeded onto fibronectin at 30 and 120 min. Importantly, ADAM8 co-immunoprecipitated with β1-integrin at both time-points, indicating that the ADAM8/β1-integrin interactions observed in JAR cells are conserved in ex vivo trophoblast cultures (Supplementary Fig. S2). Together, these findings indicate that ADAM8 physically interacts with a β1-integrin complex during the initial stages of cell attachment. Additionally, these findings imply that ADAM8 regulates the kinetics of β1-integrin localization and activity, with ADAM8-expressing cells showing accelerated attachment and more active β1-integrin signal.

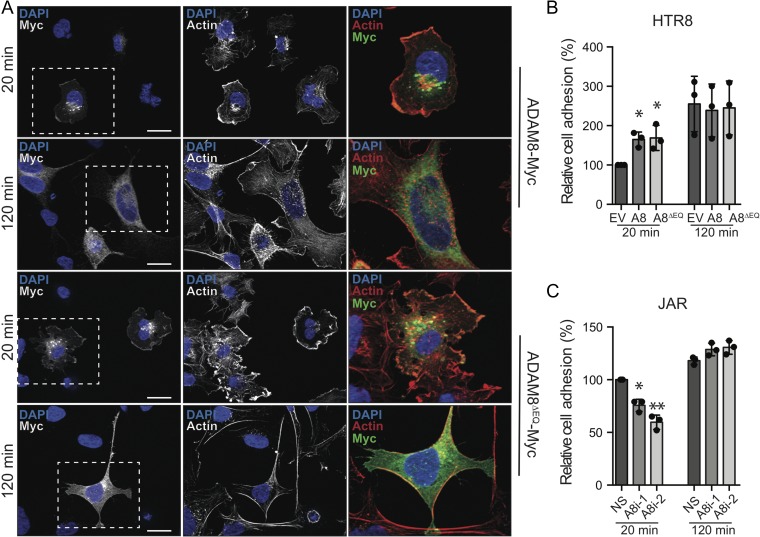

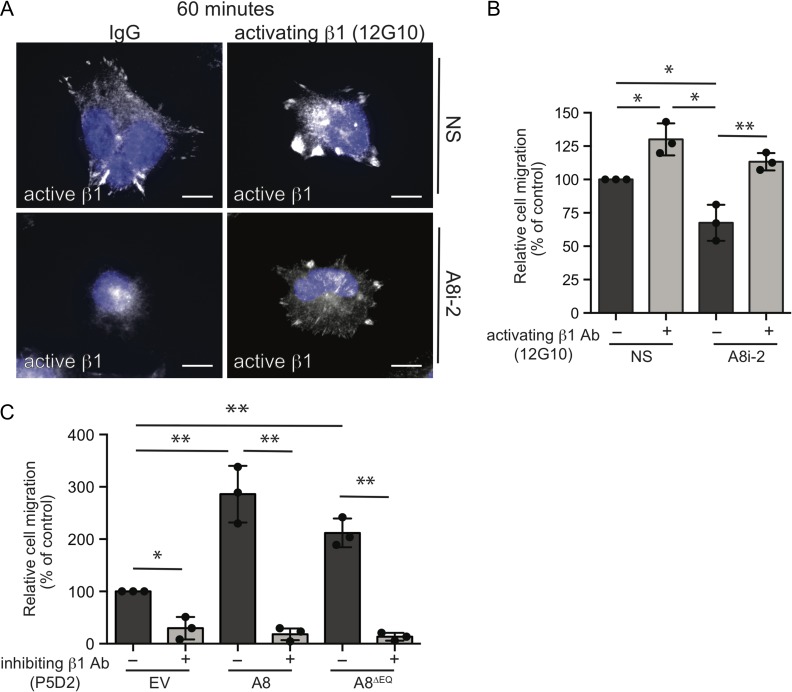

ADAM8-directed trophoblast migration requires β1 integrin engagement

To examine if ADAM8-directed alterations in β1-integrin localization and activity affect trophoblast migration, we tested if triggering β1-integrin activity in JAR cells could rescue the decrease in cell migration observed in ADAM8-silenced cells. Stimulation of both control and ADAM8 (A8i-2) siRNA-transfected JAR cells with the 12G10 β1-integrin activating antibody resulted in strong active β1-integrin signal (Fig. 6A). In control IgG-treated cells, active β1-integrin signal was observed only in NS-transfected cells with little/no punctate β1-integrin signal observed in ADAM8-silenced cells (Fig. 6A). Consistent with our earlier findings, ADAM8-silencing in JAR cells led to impaired cell migration (Fig. 6B). However, treatment of ADAM8-silenced cells with activating β1-integrin antibody promoted cell migration to levels observed in wild-type cells; migration levels of control NS-transfected cells were also potentiated in the presence of activating antibody (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

ADAM8 promotes trophoblast migration through a β1-integrin-dependent mechanism. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of control (NS) or ADAM8-silenced (A8i-2) JAR cells immunolabelled with an antibody recognizing active β1-integrin (12G10; white) following 60 min of culture on fibronectin-coated coverslips. Nuclei are labeled with DAPI (blue). Bars = 20 μm. (B) Bar graphs show relative migration of control (NS; n = 3) and ADAM8-silenced (A8i-2; n = 3) JAR cells cultured in the absence (−) or presence (+) of an activating β1-integrin antibody. (C) Bar graphs show relative migration of HTR8 cells ectopically expressing empty vector (EV), full-length ADAM8 (A8) or protease-dead ADAM8 (A8∆EQ) cultured in the absence (−) or presence (+) of inhibitory β1-integrin antibody (P5D2). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01; one-way ANOVA (Dunn’s multiple comparisons test).

To investigate if the pro-migratory effect of ectopic ADAM8 on HTR8 cells is also dependent on β1-integrin, control and ADAM8-expressing cells were treated with a function inhibiting β1-integrin antibody (clone P5D2) (Wang et al., 2015). In control cells not expressing ADAM8, P5D2 treatment resulted in a modest reduction in cell migration (Fig. 6C). Importantly, the ADAM8-directed increase in cell migration in full-length and protease-dead ADAM8-expressing cells was essentially blocked in the presence of P5D2 (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that both endogenous and ectopic forms of ADAM8 promote trophoblast cell migration through a mechanism that modulates β1-integrin function.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate that ADAM8 mRNA localizes preferentially to HLA-G+ trophoblasts within placental anchoring columns and to invasive interstitial EVTs within decidual tissue. We show that ADAM8 levels increase during EVT differentiation, where ADAM8 silencing impairs EVT migration. Within trophoblastic cell lines, ADAM8 promotes cell migration by facilitating cell–matrix attachment. Notably, ADAM8-directed cell–matrix adhesion and migration do not require ADAM8’s intrinsic protease activity. However, we provide evidence that ADAM8 directs trophoblast migration by potentiating β1-integrin activity. Together these findings shed light on the role of ADAM8 in human placental development, where ADAM8 controls trophoblast differentiation along the EVT pathway.

The expression of multiple ADAM genes have now been described within specific trophoblast populations of the human placenta and have been ascribed specific roles in coordinating trophoblast functions. In particular, ADAM proteins have been immunolocalized to villous progenitors (Aghababaei et al., 2015), proximal and distal cells of anchoring columns (Aghababaei et al., 2014; Biadasiewicz et al., 2014; De Luca et al., 2017), syncytiotrophoblast (Aghababaei et al., 2015) and to invasive interstitial EVT (Biadasiewicz et al., 2014; De Luca et al., 2017). The importance of specific ADAM proteins with respect to trophoblast function have been characterized; ADAM12 and ADAM28 promote trophoblast migration and anchoring column outgrowth (Aghababaei et al., 2014; Biadasiewicz et al., 2014; De Luca et al., 2017), where ADAM12 also potentiates villous trophoblast differentiation into the multinucleated syncytiotrophoblast (Aghababaei et al., 2015). Our finding that ADAM8 mRNA and protein localizes to multiple trophoblast subtypes within the first trimester placental villi suggests that ADAM8 performs diverse cellular function in placental development. While the focus of this study examined the functional importance of ADAM8 in EVT differentiation and migration, the presence of ADAM8 in progenitor villous trophoblasts and to syncytial structures indicates that ADAM8 may also play important roles in progenitor trophoblast homeostasis and syncytiotrophoblast formation. Further, RNAScope examination suggests that gestational age may influence ADAM8 expression within anchoring columns, as ADAM8 signal was robustly present in most column trophoblasts in early first trimester samples, while in the sole late first trimester sample analyzed (10 weeks’ gestation), ADAM8 appeared to preferentially localize to distal column cells. While further studies are required to dissect the contribution of ADAM8 to these cellular processes, this and previous studies clearly highlight the importance of ADAM-related proteases in regulating cellular processes in early placental development.

ADAM proteases control diverse cellular processes through cell surface shedding of membrane bound proteins, including growth factor receptors, cell adhesion molecules and cytokines (Weber and Saftig, 2012). To this end, ADAMs are attractive gene candidates for controlling cellular processes critical to EVT function. ADAM12 and ADAM28, initially identified by gene microarrays as being abundantly expressed in invasive EVTs (Bilban et al., 2009), promote EVT invasion and anchoring column outgrowth (Aghababaei et al., 2014; Biadasiewicz et al., 2014; De Luca et al., 2017). While ADAM12 promotes EVT invasion and column outgrowth through a mechanism requiring its intrinsic protease activity (Aghababaei et al., 2014), specific substrates central to promoting ADAM12-directed invasion have not been identified. In contrast, we provide evidence that ADAM8 promotes trophoblast migration through a molecular process independent of its intrinsic protease activity. This finding is intriguing as previous work examining the importance of ADAM8 in tumorigenic processes (i.e. invasion, metastasis, survival) identify ADAM8’s metalloprotease function as being central to its function, but, in line with our findings, also provide evidence that ADAM8’s disintegrin and cysteine-rich domains control ADAM8-directed migration and cell adhesion (Romagnoli et al., 2014). Of note, pro-form levels of ADAM8 protein were consistently greater than the active-form of ADAM8, indicating that conversion of ADAM8 into an active membrane-bound form is tightly controlled. Understanding the rate-limiting steps in ADAM8 processing in trophoblasts deserves further examination. Importantly, the disintegrin- and cysteine-rich ancillary domains of ADAM8 and other members of the ADAM family (i.e. ADAM12) promote cell–matrix interactions that are independent of intrinsic metalloprotease activity (Romagnoli et al., 2014; Schlomann et al., 2015; Eckert et al., 2017), findings that are consistent with our data showing that ADAM8-directed trophoblast–matrix adhesion and migration functions via β1-integrin.

Cell migration is a step-wise process that involves cell–matrix attachment, an important feature for generating cell tractile force required for cell movement (Wehrle-Haller, 2012). To this end, cell–matrix attachment is partially facilitated by integrin cell adhesion molecules (Truong and Danen, 2009). In particular, engagement of the fibronectin receptor (α5β1 integrin) promotes trophoblast migration, and in addition to this, promotes the differentiation of primary trophoblasts into EVT-like cells (Meinhardt et al., 2014; Haider et al., 2016). In this work we show that fibronectin-induced differentiation of trophoblasts into HLA-G expressing EVTs is accompanied by increased expression of ADAM8. Further, we show that ADAM8 promotes EVT cell migration, as well as trophoblastic cell line adhesion to fibronectin matrix. Ectopic expression of Myc-tagged ADAM8 shows that ADAM8 forms distinct peri-nuclear puncta during the initial stages of cell–matrix adhesion, but that this spatial localization is lost once cell spreading/attachment has completed. However, our findings related to ADAM8 ectopic expression do require tempering, as non-physiological levels of ADAM8 driven by the strong CMV promoter could lead to off-target artifacts within our expression system. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that ADAM8 regulates trophoblast migration by controlling the kinetics of cell–matrix attachment. Whether ADAM8 participates in the direct recruitment of cell–matrix binding complexes like focal adhesions remains to be tested. However, the involvement of other ADAM proteins (i.e. ADAM12, ADAM17) in controlling the formation of other actin-rich assemblies like focal adhesions, podosomes and invadopodia (Bax et al., 2004; Díaz et al., 2013; Eckert et al., 2017), suggests that ADAM8 may play similar roles in controlling actin/integrin nucleation processes important in trophoblast migration.

β1-integrin is an important integrin cell adhesion molecule in the control of EVT migration (Gleeson et al., 2001; Kabir-Salmani et al., 2004; Biadasiewicz et al., 2014). β1-integrin hetero-dimerizes with multiple alpha-integrin subunits, including α1- and α5-integrins which are used immunohistochemically to identify DCT and interstitial EVT (Biadasiewicz et al., 2014). How ADAM8 promotes trophoblast migration by modulating β1-integrin activity is not known. However, we provide evidence that ADAM8 transiently associates with β1-integrin during the initial stages of cell–matrix attachment, indicating that ADAM8 may participate in promoting β1-integrin sub-cellular localization to actin-rich structures or may help in controlling or stabilizing the active configuration of β1-integrin. Alternatively, the close association of ADAM8 with β1-integrin may serve as a docking platform for other signaling/adaptor molecules that could potentiate the β1-integrin signal. Further work is required to test the individual non-catalytic domains of ADAM8 with respect to β1-integrin activity and in relation to trophoblast adhesion and cell migration.

In summary, this study defines a novel role for ADAM8 in controlling the initial stages of trophoblast cell–matrix adhesion and cell migration. As the role of multiple ADAM genes in trophoblast biology have now been identified, it will be interesting to examine if alterations in ADAM functions relate to defects in placental development and the development of pregnancy disorders. Future work aimed at understanding how ADAM8 contributes to the development of the EVT lineage will provide needed insight into the importance of ADAM8 in normal placental development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to the hard work of staff at British Columbia’s Women’s Hospital’s CARE Program for recruiting participants to our study. We are additionally grateful to Dr Caroline Dunk, University of Toronto, Canada, who kindly gifted to us the JAR choriocarcinoma cell line and Dr Charles Graham, Queen’s University, Canada, who gifted us the HTR8/SVNeo cell line.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ role

A.G.B. and H.T.L. designed the research. H.T.L., J.A., D.L.M., B.C., J.T., J.B. and A.G.B. performed experiments and analyzed data. H.T.L. and A.G.B. wrote the article. All authors read and approved the article.

Funding

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2014-04466) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Open Operating Grant (201403MOP-325905-CIA-CAAA) to A.G.B.

References

- Aghababaei M, Beristain AG. The Elsevier Trophoblast Research Award Lecture: importance of metzincin proteases in trophoblast biology and placental development: a focus on ADAM12. Placenta 2015;36:S11–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghababaei M, Hogg K, Perdu S, Robinson WP, Beristain AG. ADAM12-directed ectodomain shedding of E-cadherin potentiates trophoblast fusion. Cell Death Differ 2015;22:1970–1984. Nature Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghababaei M, Perdu S, Irvine K, Beristain AG. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 12 (ADAM12) localizes to invasive trophoblast, promotes cell invasion and directs column outgrowth in early placental development. Mol Hum Reprod 2014;20:235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax DV, Messent AJ, Tart J, van Hoang M, Kott J, Maciewicz RA, Humphries MJ. Integrin alpha5beta1 and ADAM-17 interact in vitro and co-localize in migrating HeLa cells. J Biol Chem 2004;279:22377–22386. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beristain AG, Molyneux SD, Joshi PA, Pomroy NC, Di Grappa MA, Chang MC, Kirschner LS, Privé GG, Pujana MA, Khokha R. PKA signaling drives mammary tumorigenesis through Src. Oncogene 2015;34:1160–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biadasiewicz K, Fock V, Dekan S, Proestling K, Velicky P, Haider S, Knöfler M, Fröhlich C, Pollheimer J. Extravillous trophoblast-associated ADAM12 exerts pro-invasive properties, including induction of integrin beta 1-mediated cellular spreading. Biol Reprod 2014;90:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilban M, Haslinger P, Prast J, Klinglmüller F, Woelfel T, Haider S, Sachs A, Otterbein LE, Desoye G, Hiden U et al. Identification of novel trophoblast invasion-related genes: heme oxygenase-1 controls motility via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Endocrinology 2009;150:1000–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaSilva-Arnold S, James JL, Al-Khan A, Zamudio S, Illsley NP. Differentiation of first trimester cytotrophoblast to extravillous trophoblast involves an epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Placenta 2015;36:1412–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E Davies J, Pollheimer J, Yong HEJ, Kokkinos MI, Kalionis B, Knöfler M, Murthi P. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition during extravillous trophoblast differentiation. Cell Adh Migr 2016;10:310–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca LC, Le HT, Mara DL, Beristain AG. ADAM28 localizes to HLA-G(+) trophoblasts and promotes column cell outgrowth. Placenta 2017;55:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz B, Yuen A, Iizuka S, Higashiyama S, Courtneidge SA. Notch increases the shedding of HB-EGF by ADAM12 to potentiate invadopodia formation in hypoxia. J Cell Biol 2013;201:279–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert MA, Santiago-Medina M, Lwin TM, Kim J, Courtneidge SA, Yang J. ADAM12 induction by Twist1 promotes tumor invasion and metastasis via regulation of invadopodia and focal adhesions. J Cell Sci 2017;130:2036–2048. The Company of Biologists Ltd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourie AM, Coles F, Moreno V, Karlsson L. Catalytic activity of ADAM8, ADAM15, and MDC-L (ADAM28) on synthetic peptide substrates and in ectodomain cleavage of CD23. J Biol Chem 2003;278:30469–30477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson LM, Chakraborty C, McKinnon T, Lala PK. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 stimulates human trophoblast migration by signaling through alpha 5 beta 1 integrin via mitogen-activated protein Kinase pathway. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:2484–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaiquil VH, Swendeman S, Zhou W, Guaiquil P, Weskamp G, Bartsch JW, Blobel CP. ADAM8 is a negative regulator of retinal neovascularization and of the growth of heterotopically injected tumor cells in mice. J Mol Med 2010;88:497–505. Springer-Verlag. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider S, Meinhardt G, Saleh L, Fiala C, Pollheimer J, Knöfler M. Notch1 controls development of the extravillous trophoblast lineage in the human placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:E7710–E7719. National Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppertz B. Trophoblast differentiation, fetal growth restriction and preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens 2011;1:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir-Salmani M, Shiokawa S, Akimoto Y, Sakai K, Iwashita M. The role of alpha(5)beta(1)-integrin in the IGF-I-induced migration of extravillous trophoblast cells during the process of implantation. Mol Hum Reprod 2004;10:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt G, Haider S, Haslinger P, Proestling K, Fiala C, Pollheimer J, Knöfler M. Wnt-dependent T-cell factor-4 controls human etravillous trophoblast motility. Endocrinology 2014;155:1908–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naus S, Richter M, Wildeboer D, Moss M, Schachner M, Bartsch JW. Ectodomain shedding of the neural recognition molecule CHL1 by the metalloprotease-disintegrin ADAM8 promotes neurite outgrowth and suppresses neuronal cell death. J Biol Chem 2004;279:16083–16090. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordenfelt P, Elliott HL, Springer TA. Coordinated integrin activation by actin-dependent force during T-cell migration. Nat Commun 2016;7:13119. Nature Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onogi A, Naruse K, Sado T, Tsunemi T, Shigetomi H, Noguchi T, Yamada Y, Akasaki M, Oi H, Kobayashi H. Hypoxia inhibits invasion of extravillous trophoblast cells through reduction of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 activation in the early first trimester of human pregnancy. Placenta 2011;32:665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdu S, Castellana B, Yoona K, Chan K, DeLuca L, Beristain AG. Maternal obesity drives functional alterations in uterine NK cells. JCI Insight 2016;1:e85560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Carter AM. Deep trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodelling in the placental bed of the chimpanzee. Placenta 2011;32:400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss K, Saftig P. The ‘a disintegrin and metalloprotease’ (ADAM) family of sheddases: physiological and cellular functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2009;20:126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romagnoli M, Mineva ND, Polmear M, Conrad C, Srinivasan S, Loussouarn D, Barillé-Nion S, Georgakoudi I, Dagg Á, McDermott EW et al. ADAM8 expression in invasive breast cancer promotes tumor dissemination and metastasis. EMBO Mol Med 2014;6:278–294. EMBO Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U, Weskamp G, Kelly K, Zhou H-M, Higashiyama S, Peschon J, Hartmann D, Saftig P, Blobel CP. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J Cell Biol 2004;164:769–779. Rockefeller University Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomann U, Koller G, Conrad C, Ferdous T, Golfi P, Garcia AM, Höfling S, Parsons M, Costa P, Soper R et al. ADAM8 as a drug target in pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun 2015;6:6175. Nature Publishing Group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Romagnoli M, Bohm A, Sonenshein GE. N-glycosylation regulates ADAM8 processing and activation. J Biol Chem 2014;289:33676–33688. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada Y, Ylänne J, Mandelman D, Puzon W, Ginsberg MH. A point mutation of integrin beta 1 subunit blocks binding of alpha 5 beta 1 to fibronectin and invasin but not recruitment to adhesion plaques. J Cell Biol 1992;119:913–921. Rockefeller University Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilburgs T, Crespo ÂC, van der Zwan A, Rybalov B, Raj T, Stranger B, Gardner L, Moffett A, Strominger JL. Human HLA-G+ extravillous trophoblasts: immune-activating cells that interact with decidual leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:7219–7224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong H, Danen EHJ. Integrin switching modulates adhesion dynamics and cell migration. Cell Adh Migr 2009;3:179–181. Taylor & Francis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicky P, Haider S, Otti GR, Fiala C, Pollheimer J, Knöfler M. Notch-dependent RBPJκ inhibits proliferation of human cytotrophoblasts and their differentiation into extravillous trophoblasts. Mol Hum Reprod 2014;20:756–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicky P, Knöfler M, Pollheimer J. Function and control of human invasive trophoblast subtypes: intrinsic vs. maternal control. Cell Adh Migr 2016;10:154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Flanagan J, Su N, Wang L-C, Bui S, Nielson A, Wu X, Vo H-T, Ma X-J, Luo Y. RNAscope: a novel in situ RNA analysis platform for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J Mol Diagn 2012;14:22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Shen B, Chen L, Zheng P, Feng H, Hao Q, Liu X, Liu L, Xu S, Chen J et al. Extracellular calumenin suppresses ERK1/2 signaling and cell migration by protecting fibulin-1 from MMP-13-mediated proteolysis. Oncogene 2015;34:1006–1018. Nature Publishing Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S, Saftig P. Ectodomain shedding and ADAMs in development. Development 2012;139:3693–3709. Oxford University Press for The Company of Biologists Limited. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrle-Haller B. Assembly and disassembly of cell matrix adhesions. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2012;24:569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman MH, Trapani LM, Sieminski AL, Siemeski A, Mackellar D, Gong H, Kamm RD, Wells A, Lauffenburger DA, Matsudaira P. Migration of tumor cells in 3D matrices is governed by matrix stiffness along with cell-matrix adhesion and proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:10889–10894. National Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Fisher SJ, Janatpour M, Genbacev O, Dejana E, Wheelock M, Damsky CH. Human cytotrophoblasts adopt a vascular phenotype as they differentiate. A strategy for successful endovascular invasion? J Clin Invest 1997;99:2139–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigrino P, Nischt R, Mauch C. The disintegrin-like and cysteine-rich domains of ADAM-9 mediate interactions between melanoma cells and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 2011;286:6801–6807. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.