Abstract

Background

Operative management of displaced, intra-articular calcaneal fractures is associated with improved functional outcomes but associated with frequent complications due to poor soft tissue healing. The use of a minimally invasive sinus tarsi approach to the fixation of these fractures may be associated with a lower rate of complications and therefore provide superior outcomes without the associated morbidity of operative intervention.

Methods

We reviewed four prospective and seven retrospective trials that compared the outcomes from the operative fixation of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures via either an extensile lateral approach or minimally invasive fixation via a sinus tarsi approach.

Results

Patients managed with a sinus tarsi approach were less likely to suffer complications (OR = 2.98, 95% CI = 1.62–5.49, p = 0.0005) and had a shorter duration of surgery (OR = 44.29, 95% CI = 2.94–85.64, p = 0.04).

Conclusion

In displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures, a minimally invasive sinus tarsi approach is associated with a lower complication rate and quicker operation duration compared to open reduction and internal fixation via an extensile lateral approach.

Keywords: Calcaneus, Intra-articular fracture, Extensile lateral approach, Sinus tarsi approach, Minimally invasive

Introduction

Calcaneal fractures account for approximately 1–2% of all fractures of the human body, with an annual incidence of 11.5 per 100,000 people. Displaced intra-articular fractures comprise 60–75% of calcaneal fractures [1, 2]. Conservative management of these injuries is often sub-optimal, resulting in arthritis of the subtalar joint, malunion and poor functional outcomes [3]. In appropriately selected patients, operative fixation is therefore favoured in managing displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus [4, 5]. The traditional approach to fixation has been open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) through an extensile L-shaped lateral approach (ELA) [6]. The extensile lateral approach has traditionally been utilized for the fixation of most displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures. The skin incision is L-shaped with the horizontal limb in line with the fifth metatarsal and the vertical limb is between the Achilles tendon and fibula. The incision is carried directly to the bone in order to create thick soft tissue flaps. Proximal extension of the flap allows exposure of the subtalar joint. The primary danger with this approach is damage to the blood supply to the corner of the L-shaped flap. This area receives its blood supply from the lateral calcaneal artery [7]. The use of this approach is complicated by a relatively high risk of wound infection and breakdown [8–12]. Minimally invasive reduction and fixation techniques via a sinus tarsi approach (STA) have been developed in an attempt to avoid the potential complications associated with an extensile lateral approach [13–16]. It utilizes a small incision that is based distal to the fibula and anterior to the peroneal tendons. The smaller incision has a lower theoretical risk of damage to the sural nerve and the lateral calcaneal artery which are at risk during an extensile lateral approach. Following dissection through subcutaneous fat and fascia, the subtalar joint is identified and a small capsulotomy allows excellent visualization of the articular surface to assess reduction. Wound failure, breakdown, or infection can have devastating consequences and is extremely difficult to deal with. Any means by which these complications can be reduced should be investigated and utilized if they are proven to be effective.

Materials and methods

In December 2016, a search was conducted on the PubMed and MEDLINE databases using the keywords displaced intra-articular calcaneal fracture, open reduction and internal fixation, sinus tarsi approach, extensile lateral approach, minimally invasive and percutaneous. The references of the articles found were also reviewed to identify additional studies for inclusion. Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) sample population at skeletal maturity, (2) sample size > 1 (i.e. not a case study) and (3) investigated outcome measures (both quantitative and qualitative) between ORIF and minimally invasive fixation. Studies that included patients with bilateral or concurrent injuries secondary to trauma were not excluded from the meta-analysis due to the high rate of associated injuries with calcaneal fractures (up to 50%) and bilateral fractures (5–10%) in the general population [1].

Data were extracted by two independent reviewers with any disagreement resolved by consultation of a third reviewer. Outcome variables that were assessed included wound and neurovascular complications, rate of reoperation, operating time, time to surgery and postoperative articular displacement.

The relative risk (RR) was used as a summary statistic for dichotomous variables and weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous variables. In the present study, both fixed and random effect models were tested. In the fixed effects model, it was assumed that the treatment effect in each study was the same, whereas in a random-effects model, it was assumed that there were variations between studies. χ2 tests were used to study heterogeneity between trials. I2 statistic was used to estimate the percentage of total variation across studies, owing to heterogeneity rather than chance, with values greater than 50% considered as substantial heterogeneity. I2 can be calculated as I2 = 100% × (Q − df)/Q, with Q defined as Cochrane’s heterogeneity statistics and df defined as the degree of freedom [17]. The fixed effects model was presented when there was insignificant heterogeneity as defined by I2 < 50% and P < 0.05, whereas the random effects model was used when heterogeneity was deemed significantly with I2 ≥ 50% and P < 0.05 for heterogeneity [18]. Specific analyses considering confounding factors were not possible because raw data were not available. All P values were two-sided. All statistical analysis was conducted with Review Manager Version 5.3.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK).

Results

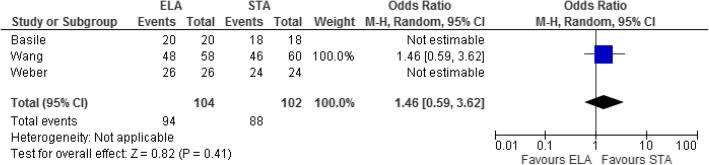

Five hundred and seventy seven studies were reviewed, of which 11 were identified that met the above criteria (Fig. 1). All studies were published from 2008 to 2016. Seven of the studies were retrospective analyses of data, with the remaining being prospective randomised trials. The final sample comprised 1131 patients in total, of whom 557 underwent ORIF via a lateral approach and 574 underwent percutaneous fixation. With bilateral injuries accounted for, there were 594 fractures in the ORIF and 622 in the percutaneous fixation group. The average age of participants was reported in 10 of the 11 studies and ranged between 30 and 46 years (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study | Type of study | ELA vs. STA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (years) | No. of patients | No. of fractures | ||

| Takasaka 2016 [22] | Retrospective | Not specified | 20 vs. 27 | 23 vs. 27 |

| Kumar 2014 [23] | Prospective | 30 vs. 31 | 21 vs. 21 | 23 vs. 22 |

| Chen 2011 [24] | Prospective | 32 vs. 31 | 40 vs. 38 | 40 vs. 38 |

| Wang 2015 [25] | Retrospective | 41 vs. 39 | 53 vs. 54 | 58 vs. 60 |

| DeWall 2010 [26] | Retrospective | 41 vs. 40 | 41 vs. 79 | 42 vs. 83 |

| Basile 2016 [27] | Prospective | 39 vs. 41 | 20 vs. 18 | 20 vs. 18 |

| Kline 2013 [28] | Retrospective | 42 vs. 46 | 79 vs. 33 | 79 vs. 33 |

| Yeo 2015 [29] | Retrospective | 42 vs. 46 | 60 vs. 40 | 60 vs. 40 |

| Xia 2014 [30] | Prospective | 37 vs. 38 | 49 vs. 59 | 53 vs. 64 |

| Wu 2012 [31] | Retrospective | 41 vs. 39 | 148 vs. 181 | 170 vs. 213 |

| Weber 2008 [32] | Retrospective | 40 vs. 42 | 26 vs. 24 | 26 vs. 24 |

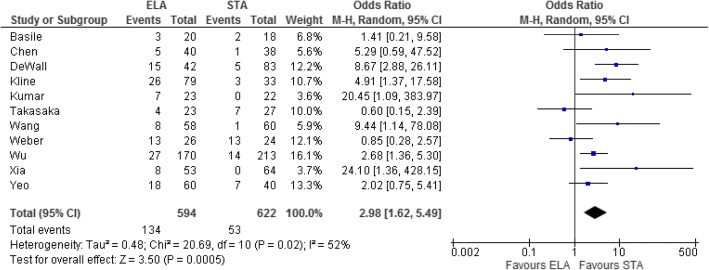

All studies investigated the occurrence of complications postoperatively (Table 2). Patients who underwent ELA were more likely to suffer postoperative complications (OR = 2.98, 95% CI = 1.62–5.49, p = 0.0005, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Complications

| Study | Complications | |

|---|---|---|

| ELA | STA | |

| Takasaka 2016 [22] | 4 (1 infection, 2 skin necrosis, and 1 sural nerve neuroma) | 0 |

| Kumar 2014 [23] | 7 (3 wound dehiscence, 1 superficial infection, and 3 deep infections) | 0 |

| Chen 2011 [24] | 5 (2 deep infections and 3 superficial wound infection) | 1 superficial wound infection |

| Wang 2015 [25] | 8 (2 deep infections and 6 poor wound healing) | 1 pin site ooze |

| DeWall 2010 [26] | 15 (9 minor wound complications and 6 deep infections) | 5 minor wound complications |

| Basile 2016 [27] | 3 (2 wound edge necrosis and 1 wound breakdown requiring skin flap) | 2 (1 mal-reduction and 1 tendon irritation requiring re-operation) |

| Kline 2013 [28] | 26 (23 wound healing and 3 sural neuropathy) | 3 (2 wound healing and 1 sural nerve neuropathy) |

| Wu 2012 [31] | 27 (12 superficial infections, 6 wound edge necrosis, 2 deep infections, 7 sural nerve neuropathy, and 4 defects with plate removal) | 14 (4 superficial infections, 3 sural nerve injuries, 7 medial injuries specific to this technique, and 4 defects with plate removal) |

| Xia 2014 [30] | 8 (6 dehiscence/superficial infection and 2 wound edge necrosis) | 0 |

| Yeo 2015 [29] | 18 (8 wound complications, 4 sural nerve injury, 1 peroneal tendonitis, and 5 subtalar stiffness) | 7 (2 wound complications, 2 sural nerve injury, and 3 subtalar stiffness) |

| Weber 2008 [32] | 13 (1 delayed wound healing, 1 hematoma, 1 sural nerve injury, 4 complex regional pain syndrome, 3 hardware removals, and 3 subsequent subtalar arthrodeses) | 11 (1 plantar nerve irritation, 10 scar tenderness at 3 months post-op requiring hardware removal) |

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for postoperative complications

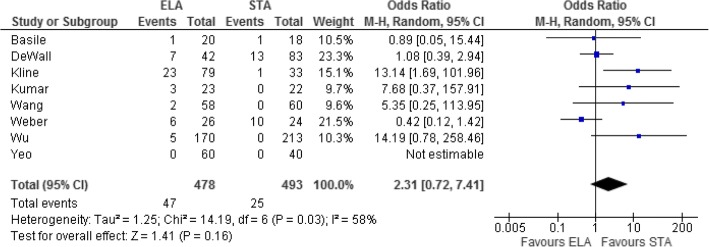

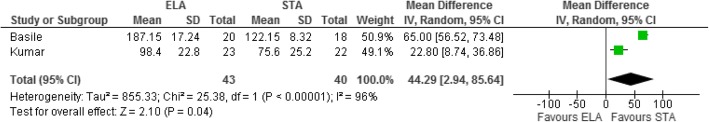

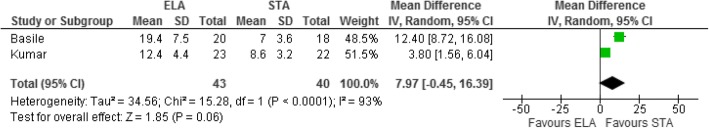

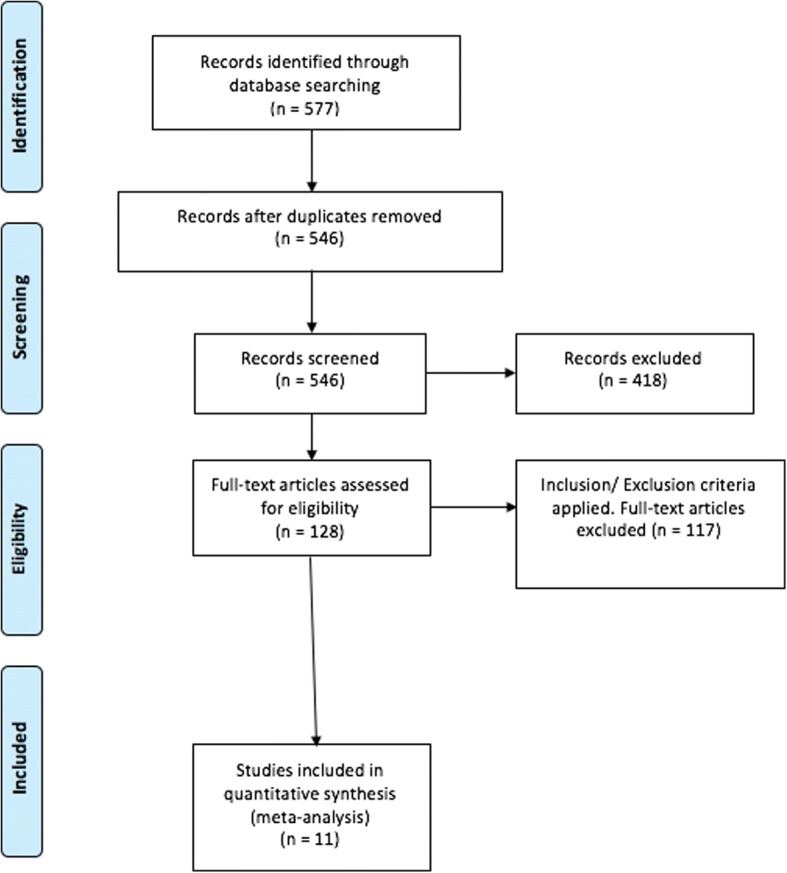

Eight studies investigated reoperation rates. Patients in the ELA group were more likely to have reoperations; however, this difference was not statistically significant (mean difference = 2.31, 95% CI = 0.72–7.41, p = 0.16, Fig. 3). STA was associated with statistically significant shorter operating times in two studies that compared the outcome (OR = 44.29, 95% CI = 2.94–85.64, p = 0.04, Fig. 4). The time taken from injury to surgery was also assessed by these two studies and suggested a faster time to operation for those in the STA group; however, this was not statistically significant (mean difference = 7.97, 95% CI = − 0.45–16.39, p = 0.06 Fig. 5). Three studies assessed postoperative articular displacement and suggested a favourable outcome after STA, but this result was not significant (OR = 1.46, 95% CI = 0.59–3.62, p = 0.41, Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for reoperation rate

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for operation duration

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for the time from injury to surgery

Fig. 6.

Forest plot for postoperative articular displacement

Additional data and outcome variables (e.g. postoperative Bohler’s angle, AOFAS score) were also measured by the studies that were unable to be included in a meta-analysis due to a lack of reported standard deviations for the values or the outcomes being assessed by only a single study, precluding formal meta-analysis.

Discussion

A review of the literature reveals a paucity of valid, objective data determining the difference between ELA and STA. Bai et al. conducted a meta-analysis of four randomised controlled trials and three cohort studies. Their study attempted to show a reduction in the complication rate and operating time; however, the inclusion of primarily cohort studies in the meta-analysis mandates caution when interpreting their results. Additionally, the total number of patients included in their meta-analysis was only 532 [19]. Zeng et al. similarly completed a meta-analysis of minimally invasive versus extensile lateral approaches for Sanders type 2 and 3 calcaneal fractures but were only able to include 495 participants from eight randomised trials [20]. Lastly, Yao et al. report a meta-analysis of 1078 participants on the topic and claim to have identified improved wound healing and functional outcomes associated with a sinus tarsi approach. Whilst promising, their meta-analysis included participants sourced from only two randomised controlled trials, with the majority of participants being from case series [21]. The results are therefore not as valid as those in the present study, due to the inherent bias associated with conducting and making conclusions based on cohort studies and case series.

These sample sizes are also substantially smaller than our population of 1131, the majority of which were sourced from randomised controlled trials which increases the validity of the present study when compared to previously published results.

From our meta-analysis, a minimally invasive sinus tarsi approach for the fixation of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures is associated with a lower rate of complications and a faster operation time when compared to ORIF via an extensile lateral approach. Soft tissue complications including deep and superficial wound infections, sural nerve damage and skin necrosis are more common in patients managed with ELA.

A major limitation of the current evidence comparing the two approaches is the lack of data on functional outcomes and post-operative articular displacement.

Seven of the studies in our meta-analysis assessed the functional outcomes (via the AOFAS) between the two approaches. However, these results were unable to be included in a meta-analysis as they were not accompanied by standard deviations. Therefore, interpretation of the raw data would lead to inaccurate conclusions regarding the patients’ functional outcomes. Further studies should therefore look at assessing the function post-operatively in a way that allows a statistical analysis of a larger sample size of patients.

Similarly, three studies (Bastille, Weber, Wang) assessed post-operative residual articular displacement based on CT scans. In spite of conventional teaching that an ELA provides improved visualization of the fracture compared to STA, there was a general trend towards less articular displacement when the STA was utilized; these results were not statistically significant (Fig. 5). Given that one of the main goals of fixation is an anatomic articular reduction which will inevitably influence post-operative function, more research is definitely required in order to determine which of the two procedures yields less articular displacement. A randomised controlled trial utilizing post-operative CT scans would be very useful in studying this and should be the direction of future research on this topic.

This was a very extensive meta-analysis; however, the main limitation was the lack of uniformity of outcome reporting between the randomised trials.

Conclusion

In displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures, a minimally invasive sinus tarsi approach is associated with a lower complication rate and quicker operation duration compared to open reduction and internal fixation via an extensile lateral approach.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in the study is freely available by replicating the search strategy outlined in the methods section.

Abbreviations

- AOFAS

American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society Score

- CI

Confidence interval

- ELA

Extensile lateral approach

- OR

Odds ratio

- ORIF

Open reduction and internal fixation

- RR

Relative risk

- STA

Sinus tarsi approach

- WMD

Weighted mean difference

Authors’ contributions

CM, VA and KP collected data and were involved in writing the paper. BS, AK and MS were involved in the conception of the study design and review and editing of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was sought and the study was approved by the institutional review board at Westmead Hospital.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. No consent was needed as the study involved the analysis of pre-published data as part of a meta-analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

This meta-analysis of the current literature reviews the difference in outcome following the fixation of displaced, intra-articular calcaneal fractures via either an extensile lateral or a minimally invasive sinus tarsi approach.

Contributor Information

Cyrus Rashid Mehta, Phone: +61 434 836 170, Email: cyrusmehta1@gmail.com.

Vincent V. G. An, Email: vian2424@uni.sydney.edu.au

Kevin Phan, Email: kphan.vc@gmail.com.

Brahman Sivakumar, Email: brahman.sivakumar@gmail.com.

Andrew J. Kanawati, Email: andrewkanawati@yahoo.com.au

Mayuran Suthersan, Email: msuthersan@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Egol KA, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD. Handbook of fractures. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders R. Displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(2):225–250. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein N, Chandran S, Chou L. Current concepts review: intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(1):79–86. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley R, Tough S, Mccormack R, Pate G, Leighton R, Petrie D, Galpin R. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(10):1733–1744. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200210000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thordarson DB, Krieger LE. Operative vs. nonoperative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: a prospective randomized trial. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17(1):2–9. doi: 10.1177/107110079601700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung F. Chapter-40 calcaneus fractures: open reduction and plate fixation. Mastering orthopedic techniques: intra-articular fractures. 2013. pp. 501–508. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calcaneus. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www2.aofoundation.org/wps/portal/surgery?bone=Foot&segment=Calcaneus&showPage=approach. Accessed 28 July 2018.

- 8.Al-Mudhaffar M, Prasad C, Mofidi A. Wound complications following operative fixation of calcaneal fractures. Injury. 2000;31(6):461–464. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benirschke SK, Kramer PA. Wound healing complications in closed and open calcaneal fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(1):1–6. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folk JW, Starr AJ, Early JS. Early wound complications of operative treatment of calcaneus fractures: analysis of 190 fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(5):369–372. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey EJ, Grujic L, Early JS, Benirschke SK, Sangeorzan BJ. Morbidity associated with ORIF of intra-articular calcaneus fractures using a lateral approach. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22(11):868–873. doi: 10.1177/107110070102201102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shuler FD, Conti SF, Gruen GS, Abidi NA. Wound-healing risk factors after open reduction and internal fixation of calcaneal fractures. Orthop Clin N Am. 2001;32(1):187–192. doi: 10.1016/S0030-5898(05)70202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelgaid SM. Closed reduction and percutaneous cannulated screws fixation of displaced intra-articular calcaneus fractures. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012;18(3):164–179. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biggi F, Fabio SD, D’Antimo C, Isoni F, Salfi C, Trevisani S. Percutaneous calcaneoplasty in displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14(4):307–310a. doi: 10.1007/s10195-013-0249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine DS, Helfet DL. An introduction to the minimally invasive osteosynthesis of intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Injury. 2001;32:51–54. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rammelt S, Amlang M, Barthel S, Gavlik J, Zwipp H. Percutaneous treatment of less severe intraarticular calcaneal fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;468(4):983–990. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0964-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phan K, Mobbs R. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in spine surgery, neurosurgery and orthopedics: guidelines for the surgeon scientist. J Spine Surg. 2015;1(1):19–27. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2414-469X.2015.06.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai L, Hou Y, Lin G, Zhang X, Liu G, Yu B. Sinus tarsi approach (STA) versus extensile lateral approach (ELA) for treatment of closed displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures (DIACF): a meta-analysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104(2):239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng Z, Yuan L, Zheng S, Sun Y, Huang F. Minimally invasive versus extensile lateral approach for sanders type II and III calcaneal fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2018;50:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao H, Liang T, Xu Y, Hou G, Lv L, Zhang J. Sinus tarsi approach versus extensile lateral approach for displaced intra-articular calcaneal fracture: a meta-analysis of current evidence base. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1). 10.1186/s13018-017-0545-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Takasaka M, Bittar CK, Mennucci FS, Mattos CA, Zabeu JL. Comparative study on three surgical techniques for intra-articular calcaneal fractures: open reduction with internal fixation using a plate, external fixation and minimally invasive surgery. Rev Bras Ortop (English Edition) 2016;51(3):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar VS, Marimuthu K, Subramani S, Sharma V, Bera J, Kotwal P. Prospective randomized trial comparing open reduction and internal fixation with minimally invasive reduction and percutaneous fixation in managing displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2505–2512. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Zhang G, Hong J, Lu X, Yuan W. Comparison of percutaneous screw fixation and calcium sulfate cement grafting versus open treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(10):979–985. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Wei W. Sanders II type calcaneal fractures: a retrospective trial of percutaneous versus operative treatment. Orthop Surg. 2015;7(1):31–36. doi: 10.1111/os.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dewall M, Henderson CE, Mckinley TO, Phelps T, Dolan L, Marsh JL. Percutaneous reduction and fixation of displaced intra-articular calcaneus fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(8):466–472. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181defd74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basile A, Albo F, Via AG. Comparison between sinus tarsi approach and extensile lateral approach for treatment of closed displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: a multicenter prospective study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(3):513–521. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kline AJ, Anderson RB, Davis WH, Jones CP, Cohen BE. Minimally invasive technique versus an extensile lateral approach for intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(6):773–780. doi: 10.1177/1071100713477607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeo J, Cho H, Lee K. Comparison of two surgical approaches for displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: sinus tarsi versus extensile lateral approach. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0519-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia S, Lu Y, Wang H, Wu Z, Wang Z. Open reduction and internal fixation with conventional plate via L-shaped lateral approach versus internal fixation with percutaneous plate via a sinus tarsi approach for calcaneal fractures – a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2014;12(5):475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Z, Su Y, Chen W, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Li M, Zhang Y. Functional outcome of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(3):743–751. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318253b5f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber M, Lehmann O, Sagesser D, Krause F. Limited open reduction and internal fixation of displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneum. J Bone Joint Surg Br Vol. 2008;90-B(12):1608–1616. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B12.20638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]