Abstract

Most surfaces are either static or switchable only between “on” and “off” states for a specific application. It is a challenge to develop reconfigurable surfaces that can adapt to rapidly changing environments or applications. Here, we demonstrate fabrication of surfaces that can be reconfigured for user-defined functions using visible-light-controlled Ru–thioether coordination chemistry. We modify substrates with Ru complex Ru-H2O. To endow a Ru-H2O-modified substrate with a certain function, a functional thioether ligand is immobilized on the substrate via Ru–thioether coordination. To change the surface function, the immobilized thioether ligand is cleaved from the substrate by visible-light-induced ligand dissociation, and then another thioether ligand with a distinct function is immobilized on the substrate. Different thioethers endow the surface with different functions. Based on this strategy, we rewrite surface patterns, manipulate protein adsorption, and control surface wettability. This strategy enables the fabrication of reconfigurable surfaces with customizable functions on demand.

Configuring surfaces on-demand for desired functionalities is an ongoing challenge. Here, diverse and tailorable modifications of quartz and porous silica surfaces that are rapidly and reversibly switchable by the use of visible light are achieved via ruthenium-thioether coordination.

Introduction

Manipulating surface properties is important for self-cleaning, guiding liquid flow, controlling protein adsorption, regulating cell adhesion, and many other applications1–5. The properties of stimuli-responsive surfaces can be changed using external stimuli, such as light, heat, electric field, CO2, glucose, and pH6–12. For example, the surface properties can be manipulated using pH-controlled dynamic imine-based covalent reaction13,14. Among these stimuli, light has attracted increasing attention because of its high spatiotemporal resolution and remote-control mechanism. To date, a variety of photolysis and photocoupling reactions have been utilized to control surface function15–20. However, most of the reported photoreactions result in only static and irreversible surface functions because of the irreversible formation or photocleavage of C–C or C–O bonds. Reversible surface functions have been realized by modifying surfaces with photoswitchable compounds such as azobenzene21–26, spiropyran27–29, dithienylethene30, and synthetic molecular shuttles31. Such surfaces can switch only between two functional states because photoswitchable compounds interconvert between two isomers under ultraviolet (UV)/visible-light irradiation. Reconfigurable surfaces, which can be converted into multiple states, have been constructed using photoreactions such as the photodynamic disulfide exchange reaction18, thiol–quinone methide reaction32, addition–fragmentation chain-transfer reaction33, and thiol–disulfide interconversion19. These photoreactions enable fabrication of customized surfaces on demand. However, all these reconfigurable surfaces are manipulated with UV light, which can damage biological components and shorten the lifetime of organic/polymeric materials. Furthermore, UV light cannot penetrate deeply into tissue, which is not suitable for manipulating biointerfaces in the body (e.g., surfaces on implants). Compared to UV light, visible light is not invasive, and red light in the visible region can penetrate deeply into tissue. Therefore, it is highly desirable to construct reconfigurable surfaces that are controllable by visible light.

Ligand photosubstitution is a powerful photoreaction for constructing reconfigurable surfaces. In ligand photosubstitution, a ligand in a metal complex is replaced by another one under light irradiation34. In particular, ligands on some Ru complexes can be substituted under visible light35–37. Light-controlled ligand substitution has been applied for uncaging neurotransmitters38,39, activating anticancer drugs40–43, controlling drug release44,45, actuating hydrogels46,47, and photopatterning48. In particular, we have demonstrated that red light can pass through tissue and induce photosubstitution in Ru complexes in vivo41. Although the abovementioned studies use only one-way photosubstitution, photosubstitution reactions of some Ru complexes are reversible at ambient or elevated temperatures49. For example, thioethers can substitute for the coordinated water molecules in Ru complexes in the dark via thermal substitution; water molecules can also substitute for the coordinated thioether ligands in Ru complexes under light irradiation50,51. Therefore, Ru complexes can interconvert between two states (i.e., the water-coordinated and thioether-coordinated states) in solution via reversible ligand photosubstitution. However, ligand photosubstitution has never been used to construct a system that can be reconfigured among multiple states.

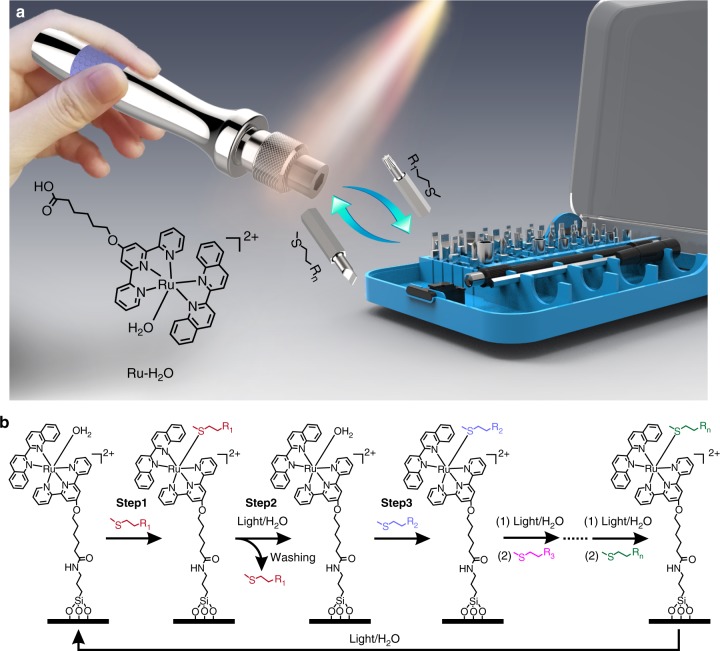

In this work, we constructed a reconfigurable surface, which can be reconfigured into a number of functional states using visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination. In our design, the Ru complex [Ru(tpy-COOH)(biq)(H2O)](PF6)2 (hereafter denoted Ru-H2O, tpy-COOH = 6-2,2’:6’,2”-terpyridin-4’-yloxy hexanoic acid, biq = 2,2’-biquinoline) acts as the molecular “multi-bit screwdriver”, and the thioethers with different functional groups (MeSC2H4-R1, MeSC2H4-R2, MeSC2H4-R3…MeSC2H4-Rn) act as the molecular bits (Fig. 1a). The removal of the bit on the screwdriver is driven by visible-light-induced photosubstitution, while the attachment of another bit to the screwdriver is automatically achieved in the dark via thermal substitution. To construct a reconfigurable surface, Ru-H2O is grafted onto a substrate (Fig. 1b). Substitution of the coordinated H2O molecule in Ru-H2O with the thioether (MeSC2H4-R1) endows the surface with the function of R1 (step 1 in Fig. 1b). To change the surface function to that of R2, MeSC2H4-R1 is first substituted by H2O under light irradiation (step 2). After washing with water and acetone to remove MeSC2H4-R1, the coordinated H2O is then substituted by MeSC2H4-R2 in the dark (step 3). The surface can be reconfigured into user-defined functions using different thioethers based on the approach in Fig. 1b. This approach enables fabrication of reconfigurable surfaces with customized functions. We demonstrate rewriting surface patterns, manipulating protein adsorption, and controlling wettability based on visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination.

Fig. 1.

Concept and mechanism of reconfiguring surface functions using visible light. a Schematic diagram of the visible-light-controlled reconfigurable multi-functional platform. Ru-H2O acts as a screwdriver, which can take a functional bit (thioethers with different functional groups) and change the function via ligand substitution. b The mechanism of reconfiguring surfaces via ligand substitution. A thioether ligand substitutes the coordinated H2O molecule in the dark and a H2O molecule substitutes a thioether ligand under visible-light irradiation. This process can occur for many times to reconfigure the surface

Results

Ru–thioether coordination in aqueous solutions

Ru-H2O was designed for this study; it has a carboxylic group for surface modification and a coordinated H2O molecule that can be substituted by thioethers (Fig. 1). Ru-H2O was synthesized via a multi-step route and fully characterized using 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, 13C NMR spectroscopy, H-H correlation spectroscopy (COSY) spectrum, and mass spectrometry (Supplementary Figs. 1–8).

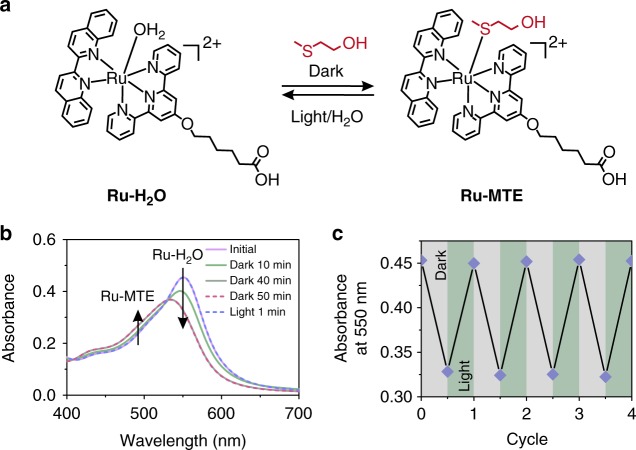

To demonstrate that the Ru–thioether bond is dynamic and reversible, we studied the coordination between Ru-H2O and a model thioether compound 2-(methylthio)ethanol (MTE) using UV–vis absorption spectroscopy (Fig. 2a). When Ru-H2O (1 mM) and MTE (10 mM) were mixed in water, the absorption band was located at 550 nm, which is attributed to the metal-to-ligand charge transfer band of Ru-H2O. The absorption band blueshifted to 535 nm and the absorbance decreased when the mixture was kept in the dark (Fig. 2b). This spectral change is identical to the observations of the formation of the Ru–thioether coordination bond reported in the literature50,51, which indicated MTE coordinated with the Ru center. The absorption band did not further blueshift after 40 min, indicating equilibrium was reached. Then, the sample was irradiated with green light (530 nm, 50 mW cm–2) for 1 min. The absorption band returned to the original position. This result showed that MTE was substituted by water upon irradiation. The existence of an isosbestic point at 530 nm suggested that a single reaction occurred. The photosubstitution of the Ru complex can also be induced by UV, blue, and red light in solution because the Ru complex has a broad absorption band in the UV and visible regions (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Note 1).

Fig. 2.

Visible-light-controlled Ru–thioether coordination in solution. a Interconversion of Ru-H2O and Ru-MTE in solution. b UV–vis absorption spectra of an aqueous solution containing Ru-H2O (1 mM) and MTE (10 mM) in the dark for 10, 40, and 50 min and subsequently irradiated with green light for 1 min. c Absorption changes in the aqueous solution containing Ru-H2O (1 mM) and MTE (10 mM) for alternating dark/light irradiation cycles

To demonstrate the reversibility of the substitution, we studied the ligand substitution for four cycles using absorption spectroscopy (Fig. 2c). In each cycle, an aqueous mixture of Ru-H2O (1 mM) and MTE (10 mM) was kept in the dark for 40 min and then irradiated with green light (530 nm, 50 mW cm–2) for 1 min. The absorption change shows that the ligand substitution was fully reversible (Fig. 2c).

We also studied the ligand substitution using 1H NMR spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Note 2). The 1H NMR data confirmed that MTE coordinated with the Ru center in the dark and was substituted by a water molecule upon green-light irradiation. The formation and cleavage of the Ru–thioether bond can be cycled for at least 10 times under dark/light irradiation conditions (Supplementary Fig. 11a). The MTE-coordinated Ru centers were approximately 80% in each cycle (Supplementary Fig. 11b and Supplementary Note 3). The equilibrium constant K of the MTE/Ru-H2O coordination reaction was 107 ± 4 M–1 at 298 K (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Note 4). The pseudo first-order rate constant k′1 was 1 × 10–3 s–1 at 298 K (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Note 5). The formation of the Ru-MTE complex in the dark was also quantified using UV–vis absorption spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Note 6). Based on these results, we conclude that the Ru–thioether bond is dynamic, and a reversible ligand substitution occurs under mild conditions without the addition of any other reagents such as catalysts or photoinitiators.

Ru–thioether coordination on surfaces

Encouraged by the reversible ligand substitution in solution, we studied visible-light-controlled Ru–thioether coordination on surfaces. To fabricate a reconfigurable surface, a quartz substrate was modified with (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) and then Ru-H2O was grafted onto the substrate via amidation. Subsequently, we vertically inserted the Ru-H2O-modified quartz substrate (1 × 2 cm2) into an MTE aqueous solution (10 mM) in a quartz cuvette and studied the ligand substitution at the surface using absorption spectroscopy. The absorption band of the grafted Ru-H2O at 550 nm decreased and slightly blueshifted in the dark. The absorption band returned to the initial state after green-light irradiation (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2) for 10 min (Supplementary Fig. 15). The spectral change was similar to that observed in solution, which indicated that the ligand substitution on the surface was reversible.

We studied the released photoproduct from the surface using mass spectrometry, which showed that MTE was intact after photoinduced releasing from the surface (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Note 7). Moreover, the surfaces were stable when stored in a fridge at –4 °C, in air and under vacuum for 5 days in the dark (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Note 8). The photostability of the Ru-MTE-modified surfaces in solution (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Note 9) and in air (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Supplementary Note 10) was also studied. The Ru-MTE-modified surfaces were stable in dry air even under UV or visible light irradiation.

The reversible substitution on the surface was quantified using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The reversible change of S 2p signal in the XPS spectra revealed that MTE was grafted on the surface in the dark and cleaved from the surface after light irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Note 11). The quantitative analysis of XPS spectra also showed that the substitution was reversible for at least 10 cycles (Supplementary Table 1). Almost all thioether ligands were cleaved from the surface after light irradiation and washing. In the dark, 49.6 to 70.9% of Ru centers (average 62%) on the surface was coordinated with MTE (Supplementary Table 1).

Rewriting surface patterns with visible light

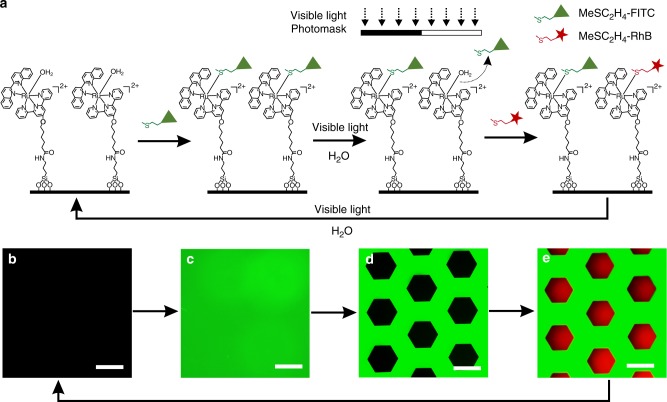

To demonstrate the reconfigurable features of the Ru-H2O-modified surface, we synthesized thioether-containing fluorescein isothiocyanate (MeSC2H4-FITC) and thioether-containing rhodamine B isothiocyanate (MeSC2H4-RhB) to create rewritable patterns (Fig. 3a). First, the Ru-H2O-modified surface was immersed in an aqueous solution of MeSC2H4-FITC (10 mM) in the dark for 2 h and then washed with water and acetone. The non-fluorescent surface (Fig. 3b) developed a strong green fluorescence (Fig. 3c), showing MeSC2H4-FITC was successfully immobilized on the surface. Then, the substrate was wetted with water, covered by a photomask, and irradiated using green light (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2) for 10 min. The disappearance of the fluorescence in the exposed regions demonstrated that MeSC2H4-FITC was cleaved from the surface (Fig. 3d). After that, the substrate was immersed into an aqueous solution of MeSC2H4-RhB (10 mM) in the dark for 2 h and then washed with water and acetone. Red fluorescence appeared in the previously exposed regions (Fig. 3e), which suggested MeSC2H4-RhB was immobilized on the surface. Moreover, the well-defined structure showed that the visible-light-induced ligand substitution can pattern different functional ligands with a good spatial resolution. Importantly, the patterned surface returned to the original state upon irradiation with green light in water, revealing the rewritable feature of the Ru-H2O-modified surface.

Fig. 3.

Rewriting surface patterns on the Ru-H2O-modified substrate using visible light. a Schematic illustration of the rewriting surface patterns. The fluorescence microscopy images of b the Ru-H2O-modified substrate, c Ru-MeSC2H4-FITC-modified substrate, d patterned substrate consisting of a Ru-MeSC2H4-FITC-modified part (green) and Ru-H2O-modified part (dark), and e patterned substrate consisting of a Ru-MeSC2H4-FITC-modified part (green) and Ru-MeSC2H4-RhB-modified part (red). Scale bars are 300 µm

Manipulating protein adsorption with visible light

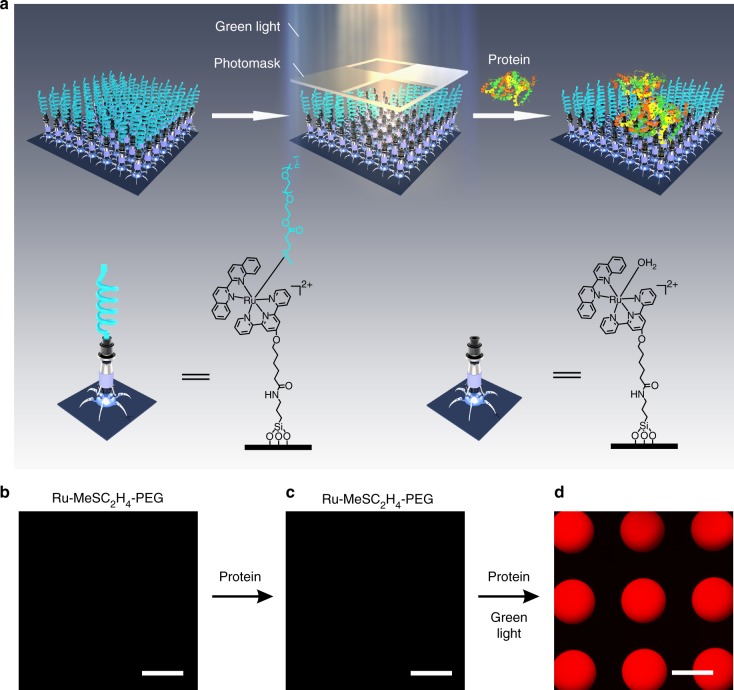

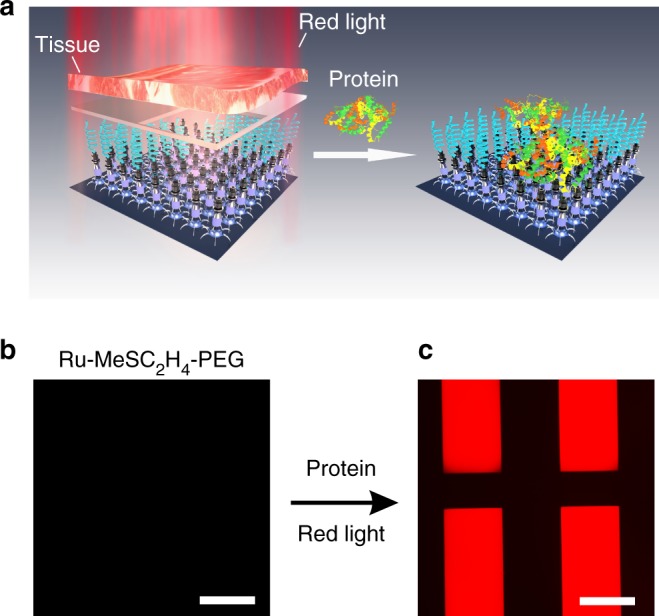

Surfaces that either resist or enhance protein adsorption are important for biomedical applications. Visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination enables reconfiguration of a surface from a protein-repellent state to a protein-adsorptive state. To fabricate a protein-resistant surface, a thioether-terminated polyethylene glycol ligand (MeSC2H4-PEG) was synthesized, which can form a dynamic coordination bond with Ru-H2O (Supplementary Fig. 21). The coordination of MeSC2H4-PEG and Ru-H2O was reversible in solution (Supplementary Fig. 22). To fabricate a protein-resistant surface, MeSC2H4-PEG was immobilized on a Ru-H2O-modified surface via Ru–thioether coordination (Fig. 4a, left). The Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface was non-fluorescent (Fig. 4b). Then, the Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface was immersed into a solution of fluorescently labeled bovine serum albumin (BSA) (0.5 mg mL–1) for 2 h and washed with an aqueous solution of NaCl (1 mM, pH = 9). After this treatment, the Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface was still non-fluorescent (Fig. 4c), showing the surface was resistant to protein adsorption. To convert the protein-resistant surface into a protein-adsorptive surface, the surface was wetted with the fluorescently labeled BSA solution and irradiated with masked green light (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2) for 10 min (Fig. 4a, middle and right). The MeSC2H4-PEG on the exposed areas was cleaved from the surface and the fluorescently labeled BSA was captured by the exposed regions via electrostatic interactions (Fig. 4d). These results demonstrate that visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination can manipulate protein adsorption.

Fig. 4.

Controlling protein adsorption with visible light. a Schematic illustration of the conversion of a protein-resistant surface into a protein-adsorptive surface with light. The fluorescent images of the b Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface, c Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface after immersion in a solution of fluorescently labeled BSA (0.5 mg mL–1) for 2 h and washing with an aqueous solution of NaCl (1 mM, pH = 9), and d protein pattern fabricated using the approach in a. Scale bars are 300 µm

Manipulating protein adsorption on biomaterials in the body (e.g., implants) with light requires light that can penetrate deeply into tissue. We have demonstrated that red light can pass through biological tissue and activate Ru complexes with absorption and photoreactivity properties similar to Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG41,52. To test the potential deep-tissue applications of the Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface, we placed a piece of 4-mm-thick pork tissue between the Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface and a red laser (671 nm, 110 mW cm–2). The surface was wetted with the fluorescently labeled BSA solution (0.5 mg mL–1) and irradiated with masked red light for 40 min (Fig. 5a). The exposed areas changed from non-fluorescent to fluorescent after light illumination, which indicated the proteins were adsorbed on the exposed areas (Fig. 5b, c). The laser wavelength (671 nm) is in the therapeutic window (600–1000 nm) and the laser intensity (110 mW cm–2) is lower than the maximum permissible exposure for skin exposure (200 mW cm–2)53,54. Therefore, manipulating protein adsorption using our system is a noninvasive method for deep-tissue applications. Furthermore, we tested biocompatibility of Ru-H2O-modified surfaces by measuring cell viability with a quartz substrate or a Ru-H2O-modified quartz substrate (Supplementary Fig. 23 and Supplementary Note 12). The biocompatibility of Ru-H2O-modified quartz is comparable to unmodified quartz.

Fig. 5.

Protein resistance and capture under tissue. a Schematic illustration of the fabrication of a protein pattern using red light after the light passes through a piece of tissue. Florescence microscopy images of a Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG-modified surface wetted with the fluorescently labeled BSA solution (b) before and c after red-light irradiation through the tissue and photomask. Scale bars are 300 µm

Controlling wettability with visible light

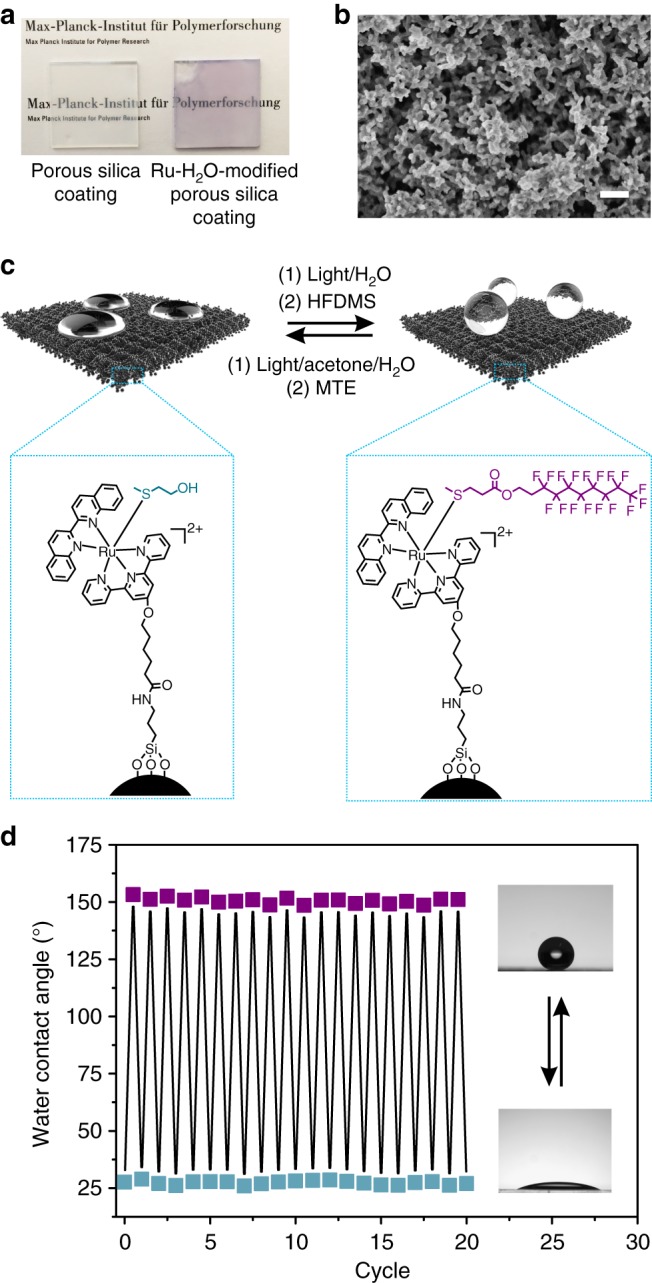

Another application of visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination is manipulating the wettability of surfaces. We can adjust the wettability using suitable thioether ligands and switch the wettability with visible light. As a proof of concept, we prepared a surface that showed reversible hydrophilic-to-superhydrophobic transitions (Fig. 6). For this purpose, we prepared a porous silica coating, which was created from a candle soot template developed in our previous work55 (Fig. 6a, b and Supplementary Fig. 24). The coating was grafted with APTES and subsequently modified with Ru-H2O. The coating was purple after it was modified with Ru-H2O (Fig. 6a, right).

Fig. 6.

Visible-light-controlled reversible switching of the surface wettability. a Photographs of the porous silica coating before and after modification with Ru-H2O. b Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the Ru-H2O-modified porous silica coating. Scale bar is 400 nm. c Schematic illustration of the reversible hydrophilic-to-superhydrophobic transitions based on visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination. d Change in the static contact angles when the ligands on the surface were interconverted between MTE and HFDMS. Blue squares indicate MTE ligands on the surface. Purple squares indicate HFDMS ligands on the surface

MTE was used as the hydrophilic thioether ligand and (3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,9,9,10,10,10-heptadecafluorodecyl)(methyl)sulfane (HFDMS) was used as the hydrophobic thioether ligand (Supplementary Fig. 25). The coordination of HFDMS and Ru-H2O was also reversible in solution (Supplementary Fig. 26). The coating with these two thioether ligands can be interconverted via visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination (Fig. 6c). First, the Ru-MTE-modified coating was prepared by immersing the Ru-H2O-modified substrate into an aqueous solution of MTE (10 mM) for 2 h in the dark, and the coating had a static water contact angle of 27 ± 2° (Fig. 6d). The low contact angle is because of the nanostructure of the coating and the hydrophilic feature of the surface groups. Subsequently, MTE was cleaved from the surface by irradiating the coating with green-light irradiation (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2, 10 min) in water. After that, HFDMS was immobilized on the substrate by immersing the substrate into an acetone/H2O (1/1) solution of HFDMS (10 mM) in the dark for 2 h and washing with acetone. After drying, the coating had a static water contact angle of 154 ± 2° and a roll-off angle less than 2°. This result shows the coating changed from hydrophilic to superhydrophobic because of the low surface free energy of the fluorocarbon chains. To switch the coating back to the hydrophilic state, the Ru-HFDMS-modified coating was irradiated with green light (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2, 10 min) in an acetone/H2O mixture and immersed into an aqueous solution of MTE (10 mM) for 2 h in the dark. The hydrophilic-to-superhydrophobic transitions were recyclable (Fig. 6d). Our reconfigurable surfaces based on the Ru–thioether dynamic bond are different from conventional photoswitchable surfaces based on photoisomerization. Conventional photoswitchable surfaces have two steady states. We can endow the surface with multiple steady states. As a proof of concept, we demonstrated the wettability of the surface can also be switched between a hydrophilic state and a hydrophobic state using another thioether (Supplementary Fig. 27 and Supplementary Note 13).

Discussion

In conclusion, we showed a universal strategy for constructing dynamic surfaces that can be reconfigured into user-defined functional states using visible-light-controlled metal–ligand coordination. As a proof of concept, we demonstrated rewriting surface patterns using Ru-MeSC2H4-FITC and Ru-MeSC2H4-RhB coordination, manipulating protein adsorption using Ru-MeSC2H4-PEG coordination, and controlling wettability using Ru-MTE, Ru-HFDMS and Ru-DMS coordination. In principle, customizable surfaces can be readily obtained using desirable thioether ligands, which are either commercially available or can be easily synthesized by modifying MTE, 3-(methylthio)propionic acid, or 2-(methylthio)ethylamine. The highly customizable functions of thioether ligands can endow the Ru–thioether-modified surfaces with different applications. The functions and applications can be easily reconfigured with visible light, which is a noninvasive stimulus. Importantly, the reported reconfigurable surfaces were also responsive to red light, which can penetrate deeply into tissue for biomedical applications. We believe that our strategy is versatile for customizable surface functionalization and opens exciting opportunities for a wide range of applications.

Methods

Synthesis

Detailed procedures for the synthesis and characterization of the Ru complexes and ligands are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Modifying quartz substrates with Ru-H2O

First, a quartz substrate (2 × 2 cm2) was immersed in piranha solution (H2SO4/H2O2 = 2/1) for 1 h at 90°, washed with water, ethanol, and acetone, and dried using a stream of N2. Then, the substrate was immersed in an ethanol solution of 1% APTES for 24 h, washed with water, ethanol, and acetone, and dried using a stream of N2. Afterwards, the substrate was immersed into a dry dichloromethane (DCM) solution (10 mL) of Ru-H2O (100 mg, 0.097 mmol), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N’-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 68 mg, 0.355 mmol), and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, 40 mg, 0.327 mmol) for 24 h before it was washed with water, ethanol, and acetone, and finally dried using a stream of N2.

Rewriting surface patterns with visible light

First, FITC and RhB were separately dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (20 mg mL–1). Subsequently, the FITC (0.96 mL, 0.05 mmol) and RhB (1.35 mL, 0.05 mmol) solutions were added into 4.04 mL and 3.65 mL aqueous MTE solutions (0.05 mmol), respectively, and stirred overnight to obtain FITC- and RhB-modified thioethers (MeSC2H4-FITC and MeSC2H4-RhB). Afterwards, the Ru-H2O-modified substrate was immersed into a MeSC2H4-FITC solution (10 mM) in the dark for 2 h, and washed with water and acetone. After drying with a stream of N2, the Ru-MeSC2H4-FITC-modified substrate was wetted by water, covered by a photomask, and irradiated using green light (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2) for 10 min. After it was washed and dried again, the substrate was immersed into a MeSC2H4-RhB solution (10 mM) in the dark for 2 h to form a patterned surface. To regenerate the Ru-H2O-modified surface, the patterned surface was irradiated with green light (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2) in water for 10 min. The substrate was imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope (DMi8, Leica).

Manipulating protein adsorption with visible light

A Ru-H2O-modified substrate was immersed into an aqueous solution of MeSC2H4-PEG (10 mL, 10 mM) in the dark overnight, washed with water and acetone, and dried using a stream of N2. Afterwards, the substrate was wetted by the fluorescently labeled BSA (0.5 mg mL–1) solution and irradiated with green light (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2) with a photomask for 10 min. Subsequently, the light was turned off, and the substrate was kept in the dark for 10 min. After washing and drying, the substrate was imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

For the deep-tissue protein adsorption experiment, a piece of 4-mm-thick pork tissue and a red laser (671 nm, 110 mW cm–2) were used. First, the Ru-H2O-modified substrate was immersed into an aqueous solution of MeSC2H4-PEG (10 mL, 10 mM) in the dark overnight. Then, the substrate was washed with water and acetone, and dried using a stream of N2. Afterwards, the substrate was wetted by the fluorescently labeled BSA solution (0.5 mg mL–1) and placed between the red laser and a photomask covered with the tissue. After irradiation for 40 min, the laser was turned off, and the substrate was kept in the dark for 10 min. After washing and drying, the substrate was imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope.

Ru-H2O-modified porous silica coating

The porous silica coating (2 × 2 cm2) was prepared according to our previous work55. First, the candle soot-coated substrate was deposited by tetraethoxysilane using chemical vapor deposition for 72 h. Afterwards, the substrate was heated at 600 °C in air for 4 h to remove the carbon cores. Subsequently, the substrate was treated with oxygen plasma for 2 s and then placed into an ethanol solution of 1% APTES for 24 h. After that, the substrate was immersed in a dry DCM solution (10 mL) of Ru-H2O (100 mg, 0.097 mmol), EDC (68 mg, 0.355 mmol), and DMAP (40 mg, 0.327 mmol) for 24 h. After washing and drying, the Ru-H2O-modified porous silica coating was obtained.

Reversible surface wettability

To obtain a hydrophilic surface, the Ru-H2O-modified porous silica coating was immersed in an aqueous solution of MTE (10 mL, 10 mM) for 2 h in the dark, washed with acetone and water, and dried using a stream of N2. To switch the hydrophilic surface to a superhydrophobic/hydrophobic surface, the hydrophilic Ru-MTE-modified coating was immersed into water and irradiated with green light (530 nm, 40 mW cm–2) for 10 min to cleave the MTE, washed with acetone and water, and dried using a stream of N2. After that, the coating was immersed into an acetone/H2O mixed solution of HFDMS or DMS (10 mL, 10 mM) for 2 h in the dark, washed with acetone, and dried with a stream of N2 to obtain a superhydrophobic/hydrophobic surface. The reversible hydrophilic-to-superhydrophobic/hydrophobic transitions were induced using the procedure mentioned above. The static water contact angles were measured using a contact angle meter (Dataphysics OCA35) by placing a 10 µL water droplet on each sample.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, WU 787/2-1, WU 787/8-1, and WU 787/10-1), the Thousand Talents Plan, and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (FCI, No. 661548). X.D. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21603026) and the Max Planck Partner Group grant. C.X. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31700841) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M612939, 2018T110960). The authors thank J. Pereira, G. Glasser, G. Schaefer, S. Backfisch, and G. Herrmann for their technical support.

Author contributions

S.W. conceived the idea. S.W. and X.D. led the project. C.X., S.W., X.D, and H.-J.B. designed the experiments. C.X., W.S., A.K., J.L., M.W., H.L. and S.W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. S.W. and C.X. wrote the paper. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xu Deng, Email: dengxu@uestc.edu.cn.

Si Wu, Email: siwu@ustc.edu.cn.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06180-7.

References

- 1.Robertus J, Browne WR, Feringa BL. Dynamic control over cell adhesive properties using molecular-based surface engineering strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:354–378. doi: 10.1039/B906608J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue L, et al. Hybrid surface patterns mimicking the design of the adhesive toe pad of tree frog. ACS Nano. 2017;11:9711–9719. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b04994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao Y, et al. Bio-inspired reversible underwater adhesive. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:2218. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02387-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie JB, Li L, Knyazeva A, Weston J, Naumov P. Mechanically robust, chemically inert superhydrophobic charcoal surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:9695–9698. doi: 10.1039/C6CC04609F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hao C, et al. Superhydrophobic-like tunable droplet bouncing on slippery liquid interfaces. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7986. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeForest CA, Tirrell DA. A photoreversible protein-patterning approach for guiding stem cell fate in three-dimensional gels. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:523–531. doi: 10.1038/nmat4219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon G, et al. Visible light guided manipulation of liquid wettability on photoresponsive surfaces. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14968. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole MA, Voelcker NH, Thissen H, Griesser HJ. Stimuli-responsive interfaces and systems for the control of protein-surface and cell-surface interactions. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1827–1850. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar S, Dory YL, Lepage M, Zhao Y. Surface-grafted stimuli-responsive block copolymer brushes for the thermo-, photo- and pH-sensitive release of dye molecules. Macromolecules. 2011;44:7385–7393. doi: 10.1021/ma2010102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunderdale GJ, Urata C, Hozumi A. An underwater superoleophobic surface that can be activated/deactivated via external triggers. Langmuir. 2014;30:13438–13446. doi: 10.1021/la503492e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Tong X, Dory YL, Lepage M, Zhao Y. A CO2-switchable polymer brush for reversible capture and release of proteins. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:90–92. doi: 10.1039/C2CC36284H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, et al. Dual-responsive surfaces modified with phenylboronic acid-containing polymer brush to reversibly capture and release cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:7603–7609. doi: 10.1021/ja401000m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rozkiewicz DI, Ravoo BJ, Reinhoudt DN. Reversible covalent patterning of self-assembled monolayers on gold and silicon oxide surfaces. Langmuir. 2005;21:6337–6343. doi: 10.1021/la050438i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tauk L, Schröder AP, Decher G, Giuseppone N. Hierarchical functional gradients of pH-responsive self-assembled monolayers using dynamic covalent chemistry on surfaces. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:649–656. doi: 10.1038/nchem.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blasco E, Wegener M, Barner‐Kowollik C. Photochemically driven polymeric network formation: synthesis and applications. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1604005. doi: 10.1002/adma.201604005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaittre G, Goldmann AS, Mueller JO, Barner‐Kowollik C. Efficient photochemical approaches for spatially resolved surface functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:11388–11403. doi: 10.1002/anie.201504920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salierno MJ, et al. Phototriggered fibril-like environments arbitrate cell escapes and migration from endothelial monolayers. Biomaterials. 2016;82:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du X, et al. Reversible and rewritable surface functionalization and patterning via photodynamic disulfide exchange. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:4997–5001. doi: 10.1002/adma.201501177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Feng W, Welle A, Levkin PA. UV-induced disulfide formation and reduction for dynamic photopatterning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:13765–13769. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui J, Miguel VS, del Campo A. Light‐triggered multifunctionality at surfaces mediated by photolabile protecting groups. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013;34:310–329. doi: 10.1002/marc.201200634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weis P, Wang D, Wu S. Visible-light-responsive azopolymers with inhibited π–π stacking enable fully reversible photopatterning. Macromolecules. 2016;49:6368–6373. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichimura K, Oh SK, Nakagawa M. Light-driven motion of liquids on a photoresponsive surface. Science. 2000;288:1624–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim HS, Han JT, Kwak D, Jin M, Cho K. Photoreversibly switchable superhydrophobic surface with erasable and rewritable pattern. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14458–14459. doi: 10.1021/ja0655901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber T, et al. Switching of bacterial adhesion to a glycosylated surface by reversible reorientation of the carbohydrate ligand. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:14583–14586. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Song Y, Jiang L. Photoresponsive surfaces with controllable wettability. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. 2007;8:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2007.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Liang H, Jacob J, Naumov P. Photogated humidity-driven motility. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7429. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klajn R. Spiropyran-based dynamic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:148–184. doi: 10.1039/C3CS60181A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosario R, et al. Photon-modulated wettability changes on spiropyran-coated surfaces. Langmuir. 2002;18:8062–8069. doi: 10.1021/la025963l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edahiro Ji, et al. In situ control of cell adhesion using photoresponsive culture surface. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:970–974. doi: 10.1021/bm0493382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida K, Yamanoi Y, Yonezawa T, Nishihara H. Reversible on/off conductance switching of single diarylethene immobilized on a silicon surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9239–9241. doi: 10.1021/ja203269t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berná J, et al. Macroscopic transport by synthetic molecular machines. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:704–710. doi: 10.1038/nmat1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arumugam S, Popik VV. Attach, remove, or replace: Reversible surface functionalization using thiol–quinone methide photoclick chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8408–8411. doi: 10.1021/ja302970x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gandavarapu NR, Azagarsamy MA, Anseth KS. Photo‐click living strategy for controlled, reversible exchange of biochemical ligands. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:2521–2526. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinhard M, et al. Photoaquation mechanism of hexacyanoferrate (II) ions: ultrafast 2D UV and transient visible and IR spectroscopies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:7335–7347. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonnet S, Limburg B, Meeldijk JD, Gebbink RJK, Killian JA. Ruthenium-decorated lipid vesicles: light-induced release of [Ru (terpy)(bpy)(OH2)] 2+ and thermal back coordination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;133:252–261. doi: 10.1021/ja105025m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith NA, et al. Combatting AMR: photoactivatable ruthenium (ii)-isoniazid complex exhibits rapid selective antimycobacterial activity. Chem. Sci. 2017;8:395–404. doi: 10.1039/C6SC03028A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosnich B, Dwyer F. Bis-1,10-phenanthroline complexes of divalent ruthenium. Aust. J. Chem. 1966;19:2229–2233. doi: 10.1071/CH9662229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zayat L, Calero C, Alborés P, Baraldo L, Etchenique R. A new strategy for neurochemical photodelivery: metal−ligand heterolytic cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:882–883. doi: 10.1021/ja0278943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albani BA, et al. Marked improvement in photoinduced cell death by a new tris-heteroleptic complex with dual action: singlet oxygen sensitization and ligand dissociation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:17095–17101. doi: 10.1021/ja508272h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sgambellone MA, David A, Garner RN, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Cellular toxicity induced by the photorelease of a caged bioactive molecule: design of a potential dual-action Ru(II) complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11274–11282. doi: 10.1021/ja4045604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun W, et al. An amphiphilic ruthenium polymetallodrug for combined photodynamic therapy and photochemotherapy in vivo. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1603702. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun W, et al. Ruthenium-containing block copolymer assemblies: red-light-responsive metallopolymers with tunable nanostructures for enhanced cellular uptake and anticancer phototherapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016;5:467–473. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201500827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mari C, et al. DNA intercalating RuII polypyridyl complexes as effective photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:14421–14436. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frasconi M, et al. Photoexpulsion of surface-grafted ruthenium complexes and subsequent release of cytotoxic cargos to cancer cells from mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11603–11613. doi: 10.1021/ja405058y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He S, et al. Ultralow-intensity near-infrared light induces drug delivery by upconverting nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:431–434. doi: 10.1039/C4CC07489K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Z, Xiong Y, Etchenique R, Wu S. Manipulating pH using near-infrared light assisted by upconverting nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:13959–13962. doi: 10.1039/C6CC05287H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theis S, et al. Metallo‐supramolecular gels that are photocleavable with visible and near‐infrared irradiation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:15857–15860. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Z, He S, Butt HJ, Wu S. Photon upconversion lithography: patterning of biomaterials using near-infrared light. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:2203–2206. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schofield ER, Collin JP, Gruber N, Sauvage JP. Photochemical and thermal ligand exchange in a ruthenium (ii) complex based on a scorpionate terpyridine ligand. Chem. Commun. 2003;9:188–189. doi: 10.1039/b210607h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bahreman A, Limburg B, Siegler MA, Bouwman E, Bonnet S. Spontaneous formation in the dark, and visible light-induced cleavage, of a Ru-S bond in water: a thermodynamic and kinetic study. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:9456–9469. doi: 10.1021/ic401105v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bahreman A, et al. Ruthenium polypyridyl complexes hopping at anionic lipid bilayers through a supramolecular bond sensitive to visible light. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:10271–10280. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun W, et al. Photoactivation of anticancer ru complexes in deep tissue: how deep can we go? Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:10832–10837. doi: 10.1002/chem.201701224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu S, Butt HJ. Near‐infrared‐sensitive materials based on upconverting nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2016;28:1208–1226. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American National Standards Institute. American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers. Orlando: Laser Institute of America; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deng X, Mammen L, Butt HJ, Vollmer D. Candle soot as a template for a transparent robust superamphiphobic coating. Science. 2012;335:67–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1207115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.