Temporary employment bans for asylum seekers have lasting negative consequences for their economic integration.

Abstract

Many European countries impose employment bans that prevent asylum seekers from entering the local labor market for a certain waiting period upon arrival. We provide evidence on the long-term effects of these employment bans on the subsequent economic integration of refugees. We leverage a natural experiment in Germany, where a court ruling prompted a reduction in the length of the employment ban. We find that, 5 years after the waiting period was reduced, employment rates were about 20 percentage points lower for refugees who, upon arrival, had to wait for an additional 7 months before they were allowed to enter the labor market. It took up to 10 years for this employment gap to disappear. Our findings suggest that longer employment bans considerably slowed down the economic integration of refugees and reduced their motivation to integrate early on after arrival. A marginal social cost analysis for the study sample suggests that this employment ban cost German taxpayers about 40 million euros per year, on average, in terms of welfare expenditures and foregone tax revenues from unemployed refugees.

INTRODUCTION

European countries are struggling with the largest refugee crisis since the aftermath of World War II. Following steep increases in the number of people seeking refugee status in Europe, policymakers face a major challenge in determining how best to integrate refugees and asylum seekers into the host country’s economy and society (1). One of the most important issues involves their access to the host country labor market (2–4). Policymakers face a dilemma: On the one hand, given the costs of supporting refugees and asylum seekers after arrival, European countries would benefit from rapidly integrating them into the local labor markets so that they can start to work, become self-sufficient, and contribute to the local economy. On the other hand, European governments are often reluctant to allow new asylum seekers to work, given the uncertainty about whether their asylum claims will be approved and political concerns that they might displace native workers (5, 6).

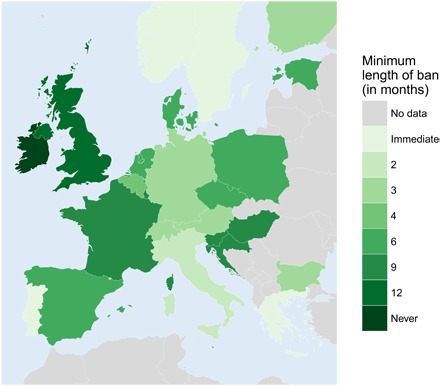

Most European governments have opted to require asylum seekers to wait before they are allowed to enter the labor market (7, 8). As shown in Fig. 1, there is considerable variation in the required wait time across European countries, with most falling between 6 and 12 months. The United States, Turkey, and other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries outside Europe have imposed similar employment bans on asylum seekers (1).

Fig. 1. Minimum length of employment bans for asylum seekers in European countries in 2016.

There is considerable heterogeneity in the length of time that asylum seekers have to wait until they can access the labor market across Europe, ranging from the day of arrival (for example, Sweden) to an indefinite ban (Ireland). The median length across countries is 6 months [data source: (1, 8)].

Proponents of employment bans often argue that letting asylum seekers access the labor market effectively integrates them into the host society during the asylum process, making deportation more difficult if their asylum claim is rejected. Work permission, they say, also acts as a pull factor and encourages even more people to apply for asylum (5, 6). In addition, employment bans may be popular with voters who worry that asylum seekers and refugees take away jobs from natives (9). Opponents argue that employment bans make it difficult for asylum seekers and refugees to gain a footing in their host country. Forced into unemployment, asylum seekers are in limbo until they can seek work. This can lead to lower motivation, depreciation of human capital, and scarring, which might slow down labor market integration for many years after the waiting period is completed (10–12). Opponents also argue that this is costly for host societies, which face higher welfare expenditures for unemployed asylum seekers and refugees and forgo the tax contributions they would have made if employed.

Despite the importance of this issue, we have very limited evidence about how employment bans affect asylum seekers and refugees. Although employment bans are in place across Europe, we are not aware of any published study that has provided causal evidence on the effects of waiting periods for accessing the labor market on the short- and long-term economic integration of refugees. Studying the effects of employment bans for asylum seekers is difficult for at least two reasons. First, there is a measurement problem because general population surveys often do not measure whether immigrants first entered the country as asylum seekers or under another immigration status. Second, it is challenging to empirically isolate the causal effects of employment bans because countries that impose waiting periods of different lengths also differ on many other confounding factors that can affect refugee employment. In addition, even if the comparison is limited to refugees who are affected by changes in the length of an employment ban within the same country, one might worry that these changes are endogenous to changes in the local labor market conditions. For example, a country might introduce or extend an employment ban because labor market conditions are deteriorating.

Here, we take a first step toward generating causal evidence on the effects of employment bans on refugee integration. In particular, we examine the short- and long-term effects of these employment bans on the economic integration of refugees. We draw on a case study in Germany, a country that has been a major European destination country for refugees in the past decades, including refugees during the Yugoslavian wars in the 90s and the present refugee crisis stemming from violence in the Middle East and Africa (13).

To address the causal identification problem, our study design leverages a natural experiment. On 22 March 2000, a court ruling prompted the German government to change the employment ban for asylum seekers from indefinite to 12 months, thereby creating exogenous variation in the amount of time that asylum seekers from different arrival cohorts had to wait before they could enter the German labor market. To address the measurement problem, we draw on the 2000–2014 waves of the German Mikrozensus. Each wave is a representative annual survey that covers 1% of the resident population. We focus on the group of immigrants from the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) who arrived in Germany in 1999 and 2000 (14). Although the Mikrozensus does not measure asylum-seeker status upon arrival, we can establish on the basis of register data that the overwhelming majority of immigrants who arrived in Germany during those years from the FRY were asylum seekers who were fleeing because of the Kosovo War.

To identify the effects of the length of the waiting period, we compare the cohorts of FRY asylum seekers who arrived in Germany in 1999 and 2000, respectively. These cohorts faced very different wait times, because the new, 12-month waiting period went into effect on 15 December 2000. This new rule also applied to asylum seekers who had arrived before 15 December 2000. Therefore, all refugees who entered in 2000 had to wait 12 months from their date of arrival before they were allowed to enter the German labor market. By contrast, refugees who entered in 1999 had to wait between 13 and 24 months, depending on when in 1999 they had arrived. For example, a refugee who had arrived in January 1999 had to wait for 24 months, while a refugee who had arrived in December 1999 only had to wait 13 months. On average, refugees in the 1999 cohort had to wait for 7.1 months longer than the 2000 cohort (see the Supplementary Materials for details). As we have shown below, these two arrival cohorts were otherwise similar across many characteristics, allowing us to isolate the short- and long-term effects of the differences in the length of the waiting period on the economic integration of the refugees. In addition, we have used various placebo checks with the FRY refugees and other immigrant groups to rule out alternative explanations. Details about the measures, sample, design, and statistical analysis can be found in Materials and Methods.

RESULTS

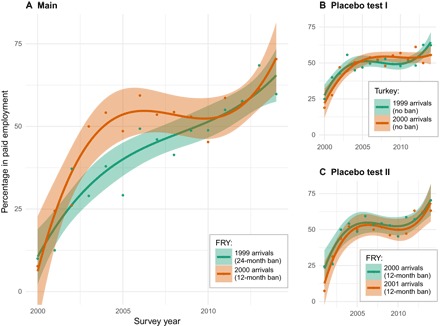

Figure 2A shows the estimated employment rates of both cohorts of FRY refugees who arrived in Germany in 1999 and 2000, respectively. We find that the 1999 cohort, who faced, on average, 7.1 months of additional wait time, experienced much lower employment rates compared to the 2000 cohort for many years following the reduction of the employment ban in 2000. While both cohorts start out with similarly low employment rates in 2000, the 2000 cohort found work much faster over the following years, whereas the employment growth among the 1999 cohort considerably lags behind. By 2005, 5 years after the ban was reduced, we find that the employment rates among the 1999 cohort are only 29%, compared to 49% among the 2000 cohort. This 20 percentage point gap in employment amounts to about a 67% difference compared to the employment rate among the 1990 cohort. After 2005, the gap starts to narrow, but it is not until 2010 (about 10 years after the ban was reduced) that the 1999 cohort catches up to the employment rate of the 2000 cohort.

Fig. 2. Longer employment bans worsen employment trajectories of refugees.

(A) Employment trajectories of FRY refugees who arrived in Germany in 1999 (green) and 2000 (red) (n = 1748). The 1999 arrival cohort faced a 13- to 24-month employment ban (depending on their month of arrival), while the 2000 arrival cohort faced a 12-month employment ban. The average difference in the length of the waiting period between the 1999 and 2000 cohorts is 7.1 months. The dots indicate the percentage of respondents who are in paid employment by survey year. The curved regression lines and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are a nonparametric approximation of the employment trajectories using regression B-splines. (B) Results of the first placebo test: Turkish immigrants who arrived in 1999 and 2000 but were not subject to the ban experienced very similar employment trajectories (n = 3712). (C) Results of the second placebo test: FRY refugees who arrived in 2000 and 2001 and were subject to the same 12-month waiting period experienced virtually identical employment trajectories (n = 1067).

One concern with the previous results might be that FRY refugees in the 1999 arrival cohort differ from the FRY refugees in the 2000 arrival cohort in important confounding characteristics that could explain the considerable gap in employment. This seems unlikely for various reasons. First, balance checks show that the two cohorts exhibit no discernible differences in terms of many demographic characteristics, such as age at arrival, gender, and education level, as well as in their answers to health-related survey items. The only exception to this are some imbalances that appear in the first Mikrozensus wave in 2000. Refugees arrived throughout that year, but the Mikrozensus was fielded in May, so the 2000 arrival cohort was only partially covered (for details, see the “Balance tests” section in the Supplementary Materials). We exclude the 2000 wave from the statistical models below and focus on the post-2000 period, when both arrival cohorts were covered. There are also no discernible differences in terms of the propensity to leave Germany. If that were the case, then we would expect the sample composition to shift over time. However, the relative sampling fraction of each cohort is fairly constant across waves (see the “Attrition check” section in the Supplementary Materials).

Second, one potentially important difference between the two cohorts is that the 1999 cohort has one additional year of residency in Germany compared to the 2000 cohort. This should, if anything, bias the comparison against finding a negative effect of the longer waiting period because much research has shown that years of residency in the host country is one of the strongest predictors of economic integration (15–17). Given that the 1999 cohort had one additional year to acquire local knowledge about Germany, learn the language, build networks, and search for opportunities, these refugees should have enjoyed a considerable advantage over those who had just arrived.

Third, if there exists a confounding characteristic that is associated with lower employment for immigrants who arrived in 1999 compared to 2000 (such as long-term consequences of differences in initial economic conditions), then we would expect that confounder to also operate on groups who did not enter as refugees and are therefore unaffected by the employment ban. Figure 2B shows the results of a placebo check that rules out this possibility. Leveraging Turkish immigrants who arrived in Germany in 1999 and 2000, most of whom were not asylum seekers and/or refugees and so were unaffected by the policy change, we find no discernible difference in the employment rates of these Turkish arrival cohorts.

In addition, Fig. 2C shows that there are also no discernible differences between the employment trajectories of FRY refugees who arrived in 2000 and 2001, respectively, and were subject to the same 12-month ban. This suggests that, in the absence of changes in the length of the waiting period, there are no confounders that independently caused a gap in employment rates between subsequent cohorts, let alone a gap of the magnitude as large as the one we find for the 1999 and 2000 FRY refugee cohorts. Together, these additional tests suggest that it is unlikely that the long-term employment effects of the ban we find are driven by differences in unobserved confounders.

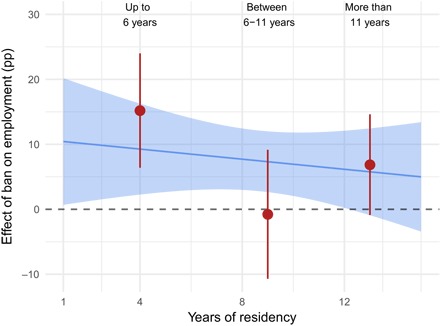

The blue line in Fig. 3 shows the estimated effects of the 7.1-month-longer average waiting period on the probability of employment for the first 16 years after arrival. These estimates are based on a statistical model where we pool the data of both the 1999 and 2000 FRY refugee arrival cohorts across all survey waves starting in 2001 and regress the employment outcome on an indicator for the 1999 and 2000 arrival cohort, the years of residency, and the interaction of the two. The model also includes a full set of survey waves fixed effects, as well as the covariates age, gender, and schooling. The 7 months of additional waiting had considerably negative short- and long-term impacts on the employment of refugees. In particular, it takes up to 10 years until the 1999 cohort recovers from the longer employment ban and is able to close the gap with the 2000 cohort. The red estimates suggest that these findings are very similar when we relax the linearity assumption on the interaction effect and use a binned interaction model (see the “Effect estimates from linear interaction and binning specification” section in the Supplementary Materials for details).

Fig. 3. Short- and long-term effects of, on average, seven additional months of employment ban on refugee employment.

The figure shows the effect of a 7-month-longer average employment ban on the probability that refugees are employed in years 1 to 16 after their arrival in Germany. The blue line shows the point estimates from the linear interaction effect model with corresponding 95% confidence interval (n = 1645). Red point estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals show the corresponding effect sizes for a binning specification that relaxes the linear interaction effect assumption and estimates the effect at the median of each tercile of the length-of-residency variable. pp, percentage point.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have provided the first evidence on the short- and long-term effects of employment bans on the subsequent employment rates of refugees, a critical aspect of their economic integration. Leveraging a natural experiment in Germany that provided exogenous variation in the length of the employment ban imposed on refugee cohorts from FRY, we find that longer employment bans had severe negative and long-lasting consequences for subsequent employment. The average 7 months of additional waiting reduced employment for up to 10 years after the ban had expired, considerably delaying the economic integration of refugees. Consistent with this, we also find a reduction in personal income (see the “Effect on reported income” section in the Supplementary Materials for details).

What mechanism might explain these effects of the longer waiting period? While the sample size limits us in answering this question definitively, additional analysis suggests that the longer waiting period considerably reduced refugees’ efforts to find work when the ban was finally lifted. Noting that the 1999 cohort exhibits lower employment levels than the 2000 cohort, we would, ceteris paribus, expect them to search more intensively for jobs. However, unemployed respondents who arrived in 1999 were much less likely than the 2000 cohort to have searched for a job during the 3 weeks before each survey wave (see the “Effect of employment ban on search effort” section in the Supplementary Materials for details). This difference in search effort is consistent with the idea that the effect of longer waiting periods could be driven by reducing refugees’ motivation to find work.

Our study has important implications for theory and policy. For theory, our findings are consistent with and contribute to the literature on the “scar” effects of unemployment (18–20). The results show that the long-term negative consequences of forced unemployment are particularly pronounced for refugees, a highly vulnerable population of individuals who often arrive in the host country without any resources and traumatized from having fled violence and war. Furthermore, the findings point to the existence of an influential early integration window. In other words, the initial period after arrival is highly consequential for the subsequent integration trajectory of refugees, and early investments yield disproportionate integration returns (17, 21, 22).

Our findings also have implications for policymakers struggling with the integration of refugees in Europe. By depressing refugees’ employment rates for many years after arrival, employment bans not only adversely affect the well-being of refugees but also impose significant costs on the host country’s economy. Refugees who struggle to find employment require increased public expenditures for welfare and make lower tax contributions. Our simple marginal social cost analysis indicates that reducing the employment ban for all 40,500 FRY refugees who arrived in 1999 by 7 months would have led to annual savings of about 40 million euros in unspent monthly welfare transfers for unemployed refugees and tax and welfare contributions from employed refugees (see the “Social cost analysis” section in the Supplementary Materials for details). This implies total marginal costs of about 370 million euros over the 2001–2009 period for FRY refugees alone. These are substantial costs for a policy with uncertain returns in light of the empirical evidence, which suggests that refugee employment has no consistent effects in depressing the wages or employment rates of natives (23, 24).

More generally, the negative effects of the longer employment ban point to a broader paradox in the unintended consequences of the European asylum regime. Governments need to honor their legal commitments under the Geneva Conventions to provide effective humanitarian protection for refugees. Still, they tend to prohibit newly arrived asylum seekers from accessing the host country’s labor market to facilitate their removal if their asylum claims are rejected. But at the same time, these initial restrictions severely slow down the economic integration of the asylum seekers who are accepted, many of whom stay in the host country indefinitely (25). Therefore, although the policy of restricting initial access might pay short-term political dividends, it backfires in the long run: Governments find themselves stuck with the long-term costs of supporting refugees with low rates of economic integration and punished by the public backlash associated with these integration failures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our statistical analysis was based on the 2000–2014 waves of the German Mikrozensus, a representative annual household survey that was conducted by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Each year, a random sample of 1% of all private households are surveyed, which results in annual samples of about 800,000 individuals. Individuals in collective dwellings, such as asylum-seeker shelters, were included in the target population. Selected respondents were required by law to participate in the survey. While the Mikrozensus provided no interpreters for the interviews, the respondents could switch to English, as well as consult with other household members. The legal duty to respond lies with the respondents, and therefore, they are required to find the help they need to respond to the survey questions.

Our main study sample consisted of immigrants who arrived in Germany from the FRY as adults (at least 18 years old) in 1999 and 2000 and have been surveyed by the Mikrozensus. Immigrants from the FRY were defined as individuals who report holding or having held a citizenship from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, Montenegro, the Republic of Kosovo, and/or the Republic of Serbia. We selected this group for two reasons. First, the large majority of immigrants who arrived from the FRY during this time period entered Germany as asylum seekers. Second, this group had a sufficient number of arrivals such that we could measure the effects of the employment ban using the annual German Mikrozensus. While there were other data sources in Germany that contain samples of (former) asylum seekers from our study period (such as the Socio-Economic Panel or Stichprobe der Integrierten Erwerbsbiografien), the Mikrozensus was the only data source in Germany that had a sufficient number of cases and contained information on immigrants’ year of arrival.

Our use of the Mikrozensus data was governed by a data use agreement with the Federal Statistical Office and did not require informed consent and institutional review board approval, given the nature of the data. We were granted permission to analyze the data, but the data itself were not transferred to us. Instead, we developed code files based on mock data and sent these code files to the staff of the Mikrozensus, who executed the code in a secure data facility and returned the results to us. The staff returned only those results that met the legal confidential criteria. All of our code files are posted in a dataverse at doi:10.7910/DVN/TZCJ83.

To estimate the effect of the difference in the waiting period that was caused by the changes in the employment ban, we compared respondents who arrived in 1999 and 2000. This information was encoded in the respondents’ answer to a question about their year of arrival in Germany (the arrival month was not available in the data). We could not distinguish between those who entered Germany as asylum seekers and entered with, for example, a work visa. Thus, all our estimates were intention-to-treat effects that could be interpreted as lower-bound estimates of the local average treatment effects. We measured the employment status of a respondent using a variable that is consistently available across survey years and encodes if a person is employed or (in)voluntarily unemployed in the survey week. Our identifying assumption was that, controlling for the covariates, the cohorts did not differ systematically in attributes other than the waiting period that also affected their employment status. We conducted a series of placebo and balance checks that lend credibility to this assumption.

Our baseline specification was a linear ordinary least-squares regression model where we interacted an indicator for the cohort (Di; 1 if 2000 and 0 if 1999) with a measure of the length of residency (Ri). We additionally included a series of control variables: age (continuous), schooling (binary), gender (binary), and survey-wave fixed effects (collected in a matrix Xi). We clustered SEs at the household level. The linear interaction specification takes the following form

| (1) |

Our central quantity of interest is β3, which identifies the differences in the employment rates between the arrival cohorts conditional on a given number of years of residency. As an additional check, we also used a binning specification that adds another interaction with an indicator for the length-of-residency variable’s tercile (Gji; short, medium, or long residency). With this specification, we could estimate the conditional effect of the cohort indicator for individuals who lived in the country for short, moderate, and long periods of time. The advantage of this specification is that it does not require assuming that the interaction effect between cohort and the length of residency is linear. We again clustered SEs on the household level for this specification. The specification of the binning estimator takes the following form

| (2) |

where rj is the median length of residency in the jth tercile, and Gij is an indicator if the ith observation is in the jth tercile. Since (Ri − rj) equals 0 when Ri = rj, the coefficients α1, α2, and α3 directly measure the conditional marginal effect of Di on yi at the median in each tercile.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Lawrence, D. Laitin, and H. Lueders for helpful conversations. Funding: We acknowledge project funding from the Swiss Network for International Studies, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the U.S. NSF (grant no. 1627339); operational support of the Immigration Policy Lab from the Ford Foundation; and funding from the Carnegie Corporation of New York (to J.H.) and the Leverhulme Trust (to D.H.). The funders had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders. Author contributions: All authors conceived the research, designed and conducted the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Replication code files for the statistical analyses and additional data and materials are available online at doi:10.7910/DVN/TZCJ83.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/9/eaap9519/DC1

Section S1. Supplementary Materials and Methods

Section S2. Descriptive statistics

Section S3. Further results

Table S1. Asylum applications from the FRY in Europe and Germany.

Table S2. Arrivals from the FRY in Germany.

Table S3. List of variables.

Table S4. Descriptive statistics for the main study sample (n = 1645).

Table S5. Descriptive statistics for the male study sample (n = 749).

Table S6. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency.

Table S7. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency (binning estimator).

Table S8. Effect of employment ban on search effort.

Table S9. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency (male respondents).

Table S10. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency (male respondents, binning estimator).

Fig. S1. Illustration of the waiting period as a function of the arrival month.

Fig. S2. Balance checks for 1999 versus 2000 FRY arrival cohort.

Fig. S3. Sampling probabilities for arrival cohorts by year.

Fig. S4. Short- and long-term effects of, on average, seven additional months of employment ban on refugee employment (male respondents).

Fig. S5. Short- and long-term effects of, on average, seven additional months of employment ban on monthly net personal income.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Making Integration Work: Refugees and Others in Need of Protection (OECD Publishing, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNHCR, A New Beginning: Refugee Integration in Europe. Outcome of an EU Funded Project on Refugee Integration Capacity and Evaluation (RICE) (2013); www.unhcr.org/52403d389.html.

- 3.Council of the European Union, Council conclusions of the council and the representatives of the governments of the member states on the integration of third-country nationals legally residing in the EU (2014); www.consilium.europa.eu/media/28071/143109.pdf.

- 4.The Economist, Getting the new arrivals to work (2015).

- 5.Valenta M., Thorshaug K., Restrictions on right to work for asylum seekers: The case of the Scandinavian countries, Great Britain and the Netherlands. Int. J. Minor. Group Rights 20, 459–482 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayblin L., Complexity reduction and policy consensus: Asylum seekers, the right to work, and the ‘pull factor’ thesis in the UK context. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 18, 812–828 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eurofound, Approaches to the Labour Market Integration of Refugees and Asylum Seekers (Publications Office of the European Union, 2016).

- 8.ECRE, Asylum Information Database Country Reports (2016).

- 9.Pew Research Center, Europeans Fear Wave of Refugees Will Mean More Terrorism, Fewer Jobs (2016); www.pewglobal.org/2016/07/11/europeans-fear-wave-of-refugees-will-mean-more-terrorism-fewer-jobs/.

- 10.Beiser M., Johnson P. J., Turner R. J., Unemployment, underemployment and depressive affect among Southeast Asian refugees. Psychol. Med. 23, 731–743 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pernice R., Brook J., Refugees’ and immigrants’ mental health: Association of demographic and post-immigration factors. J. Soc. Psychol. 136, 511–519 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinnerbrink I., Silove D., Field A., Steel Z., Manicavasagar V., Compounding of premigration trauma and postmigration stress in asylum seekers. J. Psychol. 131, 463–470 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U. Herbert, Geschichte Der Ausländerpolitik in Deutschland: Saisonarbeiter, Zwangsarbeiter, Gastarbeiter, Flüchtlinge (Beck, ed. 10, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.RDC of the Federal Statistical Office and Statistical Offices of the Länder, Mikrozensus, Wellen 1999–2014 (2018).

- 15.Chiswick B. R., The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. J. Political Econ. 86, 897–921 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Tubergen F., Maas I., Flap H., The economic incorporation of immigrants in 18 Western societies: Origin, destination, and community effects. Am. Sociol. Rev. 69, 704–727 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hainmueller J., Hangartner D., Lawrence D., When lives are put on hold: Lengthy asylum processes decrease employment among refugees. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600432 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruhm C. J., Are workers permanently scarred by job displacements? Am. Econ. Rev. 81, 319–324 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson L. S., LaLonde R. J., Sullivan D. G., Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 83, 685–709 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens A. H., Persistent effects of job displacement: The importance of multiple job losses. J. Labor Econ. 15, 165–188 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hainmueller J., Hangartner D., Pietrantuono G., Catalyst or crown: Does naturalization promote the long-term social integration of immigrants? Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 111, 256–276 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferwerda J., Finseraas H., Bergh J., Voting rights and immigrant incorporation: Evidence from Norway. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 1–18 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration (The National Academies Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foged M., Peri G., Immigrants’ effect on native workers: New analysis on longitudinal data. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 8, 1–34 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25.UNHCR, Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2015 (2016); www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2015.html.

- 26.Federal Office for the Recognition of Foreign Refugees, Der Einzelentscheider-Brief (Jahrgang 6, Ausgabe, Oktober, 1999); www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Entscheiderbrief/1999-2004/ee-brief-jahr-1999.html.

- 27.UNHCR, Population Statistics Database (2017); http://popstats.unhcr.org/en/overview.

- 28.UNHCR, Refugees and Others of Concern to UNHCR: 1998 Statistical Overview (1999); www.unhcr.org/3bfa31ac1.pdf.

- 29.UNHCR, Refugees and Others of Concern to UNHCR: 1999 Statistical Overview (2000); www.unhcr.org/3ae6bc834.pdf.

- 30.P. Kühne, H. Rüßler, Die Lebensverhältnisse der Flüchtlinge in Deutschland (Campus, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 31.GGUA-Projekt Büro, Das Arbeitsgenehmigungsverfahren für Flüchtlinge (2001); http://archiv.proasyl.de/texte/mappe/2001/43/1.htm.

- 32.Best M., Sozialgericht Lübeck: Der Blüm Erlass ist Rechtswidrig. Der Schlepper 11 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Federal Office for the Recognition of Foreign Refugees, Der Einzelentscheider-Brief (Jahrgang 7, Ausgabe, February, 2000); www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Entscheiderbrief/1999-2004/ee-brief-jahr-2000.html.

- 34.Federal Office for the Recognition of Foreign Refugees, Der Einzelentscheider-Brief (Jahrgang 8, Ausgabe, February, 2001); www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Publikationen/Entscheiderbrief/1999-2004/ee-brief-jahr-2001.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/9/eaap9519/DC1

Section S1. Supplementary Materials and Methods

Section S2. Descriptive statistics

Section S3. Further results

Table S1. Asylum applications from the FRY in Europe and Germany.

Table S2. Arrivals from the FRY in Germany.

Table S3. List of variables.

Table S4. Descriptive statistics for the main study sample (n = 1645).

Table S5. Descriptive statistics for the male study sample (n = 749).

Table S6. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency.

Table S7. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency (binning estimator).

Table S8. Effect of employment ban on search effort.

Table S9. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency (male respondents).

Table S10. Estimated difference in employment rates between 1999 and 2000 cohort by years of residency (male respondents, binning estimator).

Fig. S1. Illustration of the waiting period as a function of the arrival month.

Fig. S2. Balance checks for 1999 versus 2000 FRY arrival cohort.

Fig. S3. Sampling probabilities for arrival cohorts by year.

Fig. S4. Short- and long-term effects of, on average, seven additional months of employment ban on refugee employment (male respondents).

Fig. S5. Short- and long-term effects of, on average, seven additional months of employment ban on monthly net personal income.