Ultrastable and highly H2-selective porous organic framework membranes were successfully synthesized by interfacial polymerization.

Abstract

The development of new membranes with high H2 separation performance under industrially relevant conditions (high temperatures and pressures) is of primary importance. For instance, these membranes may facilitate the implementation of energy-efficient precombustion CO2 capture or reduce energy intensity in other industrial processes such as ammonia synthesis. We report a facile synthetic protocol based on interfacial polymerization for the fabrication of supported benzimidazole-linked polymer membranes that display an unprecedented H2/CO2 selectivity (up to 40) at 423 K together with high-pressure resistance and long-term stability (>800 hours in the presence of water vapor).

INTRODUCTION

Separation processes, mostly based on distillation, account for 10 to 15% of the world energy consumption (1). Membrane-based units offer several advantages, including a higher energy efficiency, smaller footprints, ease of operation, and environmental friendliness. It is therefore not surprising that intense research has been devoted to the development of membrane modules able to efficiently separate complex gas mixtures. Among the different membrane materials, polymers still dominate the market because of their good processability and mechanical stability (2). Nevertheless, conventional polymeric membranes suffer from a “trade-off” between gas permeability and selectivity (3–5). Extensive efforts have been put into the rational design and synthesis of novel microporous polymeric membranes to overcome this limit, including thermally rearranged (TR) polymers (6), polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIMs) (7, 8), and porous organic frameworks (POFs) such as covalent organic frameworks (COFs) (9), covalent triazine frameworks (10), porous aromatic frameworks (11), etc. Although some PIMs are highly soluble in common solvents and can be directly processed into membranes, PIM membranes suffer from moderate selectivity and serious aging issues. POFs are generally insoluble in most solvents, which greatly restricts their functionalization and postprocessing into defect-free membranes. (12) The preparation of POF membranes has been achieved by direct growth on functional substrates (9), assembly of porous nanosheets (13), or mixing these porous fillers with nonstructured and generally nonporous polymers in the form of mixed-matrix membranes (11, 14, 15). However, to date, POF-based membranes have shown poor gas separation performance, mostly due to the relatively large pores of the selected POFs and the challenge of preparing continuous, defect-free, membranes.

Benzimidazole-linked polymers (BILPs) are a class of POFs, which are synthesized via condensation of diamines and aldehydes in N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF), resulting in amorphous powders with remarkable thermal and chemical stabilities, as well as high CO2 uptakes (16, 17). Compared to other POFs, BILPs have narrower pores because of their highly cross-linked interpenetrated networks (17, 18), rendering them more suitable for the separation of small molecules. However, BILPs are nonsoluble in most solvents, making the preparation of membranes highly challenging. In this spirit, the development of more straightforward manufacturing processes for the large-scale production of continuous thin films is of great interest. Interfacial polymerization (IP) (19–24) is a facile and effective technique that allows the synthesis of large-area thin layers at the interface between two immiscible liquids. The IP method has been successfully applied for the synthesis of polyamide (20, 21) membranes on the bulk scale for water desalination and nanofiltration. Despite its potential, IP remains largely unexplored in the field of novel microporous polymer membranes for gas separation, although some COF films were recently synthesized following this approach for application in liquid-phase nanofiltration (25).

Herein, we circumvented the challenge of producing defect-free BILPs membranes [BILP-101x (18)] by using a facile room temperature IP method. The resulting membranes display an excellent H2/CO2 separation performance together with long-term stability under relevant separation conditions for precombustion CO2 capture.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

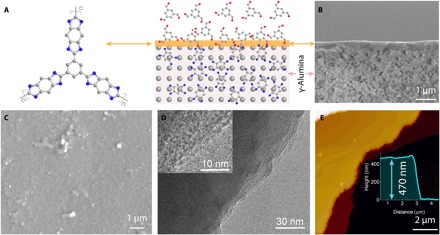

BILP-101x membranes were directly fabricated onto α-Al2O3 porous supports (γ-Al2O3 on top; pore size of the γ layer, 5 nm) by IP (Fig. 1A). α-Al2O3 was selected because of its good thermal stability. Moreover, the γ-Al2O3 layer offers a large volume of small hydrophilic pores, ideal for the IP process (26). In a typical preparation procedure, membranes were synthesized by immersing an α-Al2O3 disk in a 1.5 weight % (wt %) 1,2,4,5-benzenetetramine tetrahydrochloride (BTA) aqueous solution for 20 min. The BTA-containing aqueous solution was trapped in the small pores of the top layer of the asymmetric Al2O3 support, which, after drying the surface, was further immersed in a 0.5 wt % 1,3,5-triformylbenzene (TFB) benzene solution for 60 min (see details in Materials and Methods). Upon contact with the TFB-containing solution, the amine groups of the trapped BTA monomer quickly react with the aldehyde moieties at the water/benzene interface, leading to the rapid formation of a brown layer at the interface. The growing film itself probably becomes a barrier for the contact between the two monomers and confines the reaction to the remaining defects, resulting in the formation of a continuous, defect-free layer at the support surface. SEM images were acquired from the cross section and top surface of the membrane. A continuous membrane (Fig. 1C) with a thickness of around ~400 nm (Fig. 1B) can be observed by SEM.

Fig. 1. Scheme depicting the IP process and morphology characterization of BILP-101x membranes and freestanding films.

(A) The alumina disk was first saturated with an aqueous BTA solution and then contacted with a benzene layer containing TFB, enabling the formation of BILP-101x membranes at the interface. Gray, red, and blue spheres represent C, O, and N atoms, respectively. H atoms are omitted for clarity. (B and C) Cross-sectional and surface scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of a BILP-101x membrane (~400 nm thick) formed on alumina substrate. (D) High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of the freestanding BILP-101x film. (E) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) topographical image of the film on a silicon wafer. Inset shows the film height. The samples were prepared under the following conditions: 1.5 wt % BTA and 0.5 wt % TFB for 60 min (see details in Materials and Methods).

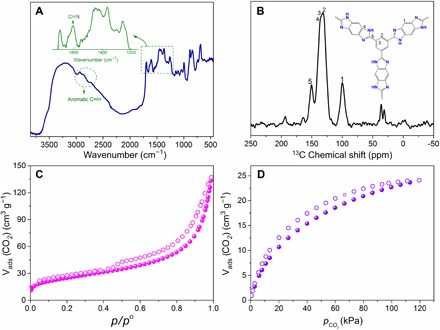

To gain insight into the structure of the membrane, freestanding films were prepared at the bulk liquid interface under identical conditions (see details in Materials and Methods). A film with lateral dimensions of up to several centimeters was transferred to a nylon substrate (fig. S2C). A sheet-like morphology can be observed by TEM (Fig. 1D and fig. S3, C and D). In some places, the layer was crumped or scrolled, suggesting its high flexibility. AFM images of a BILP film transferred onto a silicon wafer revealed an average film thickness of ~470 nm (Fig. 1E and fig. S4B), which is consistent with the membrane thickness prepared on the alumina substrate. The formation of BILP-101x was confirmed by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) and 13C cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CP/MAS) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Figure 2A reveals a characteristic stretching band at 1610 cm−1 (the C=N vibration) and bands at 1450, 1365, and 1260 cm−1, which are assigned to the formation of the benzimidazole ring (18, 27). The band at 1700 cm−1 points to the presence of some residual aldehyde groups, further corroborated by a weak peak at δ = 194 parts per million (ppm) in the solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectrum (Fig. 2B). In line with the DRIFTS results, the 13C CP/MAS NMR spectrum proves the successful condensation between TFB and BTA building units (Fig. 2B), giving rise to the appearance of a peak at a chemical shift of 150 ppm, characteristic of the benzimidazole ring. Signals centered at 130 and 100 ppm are characteristic of aromatic carbons, particularly those of the monomers. The full assignment of the peaks is shown in Fig. 2B. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) under air reveals that the film remains stable up to 523 K (fig. S5A).

Fig. 2. Spectroscopic characterization and gas adsorption measurements of BILP-101x films.

(A and B) Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) and 13C CP/MAS spectra of films. (C and D) N2 and CO2 adsorption (solid symbols) and desorption (open symbols) isotherms of the films at 77 and 298 K, respectively. The samples were prepared under the following conditions: 1.5 wt % BTA and 0.5 wt % TFB for 60 min (see details in Materials and Methods).

To study the textural properties of the prepared film, N2, Ar, and CO2 adsorption isotherms were acquired at 77, 87, and 298 K, respectively. In regards to N2 adsorption, the BILP-101x film exhibits a type II isotherm together with a type III hysteresis loop (28). The calculated Brunauer-Emmett-Teller area of the BILP-101x film was 87 m2 g−1, comprising a small amount of micropores (17 m2 g−1) and mainly external surface area (70 m2 g−1) according to the t-plot method. The micropores come from the internal structure of the film, while mesopores are expected to arise from the dense packing of film sheets. In line with N2 adsorption results, Ar adsorption also shows only a small uptake at relatively low pressures together with a similar hysteresis loop (fig. S5B), indicating its low accessibility toward Ar (~3.4 Å) and N2 (~3.6 Å). Considering the high Lewis basic N/C ratio in the BILP-101x network, it should achieve a high CO2 uptake at low pressures. However, CO2 adsorption isotherms (Fig. 2D) show a CO2 uptake of ~22 cm3 g−1 at 1 bar and 298 K, which is much lower than that of BILP-101 (18), indicating a higher degree of interpenetration in the BILP-101x solid. In the powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns (fig. S5C), the film shows a single broad reflection at 30° with a d spacing of ~3.5 Å. The d spacing is usually considered the packing distance between polymer chains, and the decrease in d is expected to increase the size-sieving ability of polymer membranes for gas separation. In our case, the small d spacing results in high hydrogen selectivity, as discussed below. Both the value of d spacing and porosity of the as-synthesized BILP-101x films are different from the BILP-101 particles reported in (18). The method for the preparation of our films is different from the earlier approach, for example, temperature, duration, solvent, and the way of monomer addition. As noticed by Pandey et al. (29) and Rabbani et al.(27), the additional speed of monomers and the temperature will influence the formation of the oligomers at the beginning of the reaction, which are important factors affecting the overall porosity of BILPs.

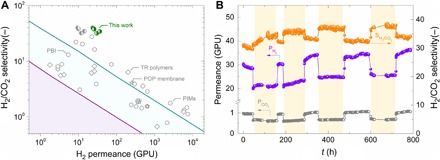

The prepared BILP membranes were mounted into a Wicke-Kallenbach cell to evaluate their performance in the separation of equimolar H2/CO2 mixtures at 423 K. This separation is very relevant for precombustion CO2 capture and H2 production. We first carried out an experiment using the α-Al2O3 substrate. The bare substrate showed a H2 permeance of >80,000 gas permeation units (GPUs) with a low H2/CO2 selectivity of ~3. The BILP-101x membrane exhibits an excellent separation performance with a H2/CO2 selectivity of 40 and a H2 permeance of 24 GPUs at 1 bar transmembrane pressure difference, surpassing not only the H2/CO2 2008 Robeson upper bound (Fig. 3A) (3) of conventional polymer membranes but also the performance of a wide range of new polymers such as PIMs, TR polymers, porous organic polymer (POP) membranes, and the benchmark polybenzimidazole (PBI) (30). Moreover, the BILP-101x membranes also demonstrate great potential for H2 recovery from ammonia production with a H2/N2 selectivity of ~87 (table S3), which is higher than H2/CO2, suggesting a molecular sieving mechanism. As discussed above, this is further supported by the PXRD of the film showing an average chain d spacing of ~3.5 Å, consequently facilitating the diffusion of molecules with small kinetic diameters (H2 ~ 2.9 Å) and hindering the transport of those with large diameters (CO2 ~ 3.3 Å and N2 ~ 3.6 Å).

Fig. 3. Performance of the prepared membranes.

(A) Comparison of H2/CO2 separation performance with previously reported polymer membranes. The lines were drawn based on the 2008 Robeson upper bound line by converting permeability to permeance assuming a membrane thickness of 50 μm (purple line) and 1 μm (green line). The membrane thickness is assumed as 1 μm for the typical PBI, TR polymers, POPs, and PIMs. The green half-filled circles represent the BILP membrane performance developed in this work. For comparison, the predicted membrane performance (gray half-filled circles) of BILP with a membrane thickness of 1 μm is calculated. The details can be found in table S4. (B) Long-term stability for H2/CO2 separation under dry and wet gas mixture [2.3 mole percent (mol %) H2O, marked by light-yellow areas] at 423 K. The samples were prepared under the following conditions: 1.5 wt % BTA and 0.5 wt % TFB for 60 min (see details in Materials and Methods).

In a typical precombustion CO2 capture process, H2 is generated through stream reforming of fossil fuels followed by water-gas shift. As a result, a high-pressure (up to ~35 bar), high-temperature (~450 to 530 K) mixture of CO2 and H2 is generated (31). To selectively separate H2 and capture CO2, membrane materials displaying high-temperature and high-pressure resistance are required (5). The separation performance of the BILP-101x membranes was further evaluated under conditions relevant for this important separation. H2/CO2 measurements under elevated temperatures (from 423 to 498 K; fig. S6) reveal an activated diffusion for both H2 and CO2. The membrane still exhibits an excellent separation performance with a H2/CO2 selectivity of 24, even at 498 K. High-pressure measurements (fig. S7) indicate that the membrane still has a high H2/CO2 selectivity (~25) even at 423 K and 10 bar feed pressure. Conventional polymers either would not withstand these conditions or exhibit limited separation performance at elevated temperatures. Some emerging ultrathin two-dimensional (2D) metal-organic frameworks and graphene oxide nanosheet membranes (32–34) could achieve a good H2/CO2 separation performance at high temperatures. However, these ultrathin membranes are vulnerable to high pressures owing to the fragile nature of single 2D nanosheets and the weak interaction between layers.

Lack of stability is the biggest hurdle faced by H2 separation membranes (31). The development of hydrothermally stable membranes is highly desired since water is inevitably present in industrial H2/CO2 separation processes. Accordingly, the long-term performance of our BILP-101x membranes under steam at 423 K was studied (Fig. 3B). Both H2 and CO2 permeances decreased when introducing 2.3 mol % steam in the feed due to the competitive sorption of water molecules on the polar imidazole ring in the membrane, which narrows the effective pathways and thus increases diffusion resistance for both gases. This competitive effect is more significant for the bigger CO2 molecules, leading to an increased H2/CO2 selectivity. Upon removing the water from the feed, the performance returns to that previously observed under dry conditions. After the 800-hour hydrothermal cycling test, both the permeance and selectivity of BILP-101x membrane were slightly increased, probably due to the release of impurities.

CONCLUSION

Overall, these results demonstrate that IP offers great advantages for the preparation of defect-free membranes based on POFs. The high H2/CO2 separation performance combined with an excellent long-term hydrothermal stability places BILP-101x based membranes among the most promising candidates to be used for H2 separation/purification under industrially relevant conditions. Moreover, the combination of such a simple preparation method with the rich chemistry of POFs is expected to result in the development of many more membranes with applications in a wide variety of separations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

TFB (97%), BTA, and benzene (anhydrous, 99.8%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and DMF (anhydrous, 99.8%) was ordered from Thermo Fisher. All the chemicals were used without further purification. Asymmetric α-Al2O3 disks (γ-Al2O3 on top) with a diameter of 18 mm and a thickness of 1 mm were purchased from Fraunhofer Institut für Keramische Technologien und Systeme (IKTS). The average pore size of the top layer is ca. 5 nm.

Synthesis of supported BILP-101x membranes

Supported BILP-101x membranes with different monomer concentrations and different layers were prepared. Table S1 lists the conditions for each membrane, and fig. S1 shows the digital photos of the prepared membranes. The membrane color becomes darker with the increase of monomer concentration. For the specific procedures, α-alumina disks were first immersed in BTA aqueous solution under reduced pressure (0.2 bar) for 20 min, dried with compressed air until no visible droplets were left on the surface, and then contacted with TFB solution in benzene for 60 min. This procedure was repeated to prepare membranes with two layers of BILP. The membranes were left overnight, washed with benzene to remove the unreacted TFB, dried at room temperature for at least 16 hours, and finally put into a homemade permeation setup for performance testing (scheme S1).

Synthesis of the BILP-101x film at the bulk liquid interface

An aqueous solution of BTA (that is, 1.5 wt %, 150 mg in 10 g of deionized water) was poured into a small petri dish (inner diameter, ~5 cm) and then a solution of TFB in benzene (0.5 wt %, 44.7 mg in 8.7 g of benzene) was gently spread on top of the BTA solution. After a few seconds, a brown layer was formed at the water-benzene interface, which was gently transferred to a nylon substrate (see fig. S2C). Plenty of films were synthesized following this procedure; washed with benzene, water, DMF, and ethanol; and finally dried under vacuum overnight at 393 K for further characterization. To get a clear view, a photo of a film synthesized in a small vial is presented in fig. S2B.

Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectra

DRIFT spectra of the BILP-101x film was acquired in a Nicolet 8700 FT-IR (Thermo Scientific) spectrometer equipped with a high-temperature cell with CaF2 windows. The samples were pretreated in He at 423 K for 30 min to collect the spectra.

Thermogravimetric analysis

TGA of the BILP-101x film was performed on a Mettler Toledo TGA/SDTA851e apparatus by measuring the mass loss of the sample while heating the prepared BILP film under air (100 ml min−1) from 303 to 1073 K at a heating rate of 5 K min−1.

Powder x-ray diffraction

PXRD patterns of the prepared films were recorded using a Bruker-D8 Advanced diffractometer with Co-Kα radiation (λ = 1.78897 Å). The samples were scanned in the 2θ range of 5° to 80° using a step size of 0.02° and a scan speed of 0.4 s per step in a continuous scanning mode.

Scanning electron microscopy

SEM micrographs of the freestanding film were acquired using a JEOL JSM-6010LA InTouchScope microscope. The images of the supported membranes were obtained using a DualBeam Strata 235 microscope (FEI) and an AURIGA Compact (Zeiss) microscope. Before the analyses, BILP-101x films and supported membranes were sputter-coated with gold.

Atomic force microscopy

AFM images were obtained by transferring the freestanding films to silica wafer and dried in an oven at 353 K for 1 hour. The images were obtained using a Veeco Multimode Nanoscope IIIA microscope operating in tapping mode.

Gas adsorption isotherms

N2 (77 K) and CO2 (298 K) adsorption isotherms were recorded in a TriStar II 3020 (Micromeritics) instrument. Ar (87 K) adsorption was performed in a 3Flex (Micromeritics) instrument. Before gas adsorption measurements, the samples were degassed at 423 K under N2 flow for at least 16 hours.

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy

1D 13C CP/MAS solid-state NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE III spectrometers operating at 600-MHz resonance frequencies for 1H. Experiments at 600 MHz used a conventional double-resonance 3.2-mm CP/MAS probe or a 2.5-mm double-resonance probe. Dry nitrogen gas was used for sample spinning to prevent degradation of the samples. NMR chemical shifts were reported with respect to the external references tetramethylsilane and adamantane. For 13C CP/MAS NMR experiments, the following sequence was used: 90° pulse on the proton (pulse length 2.4 s), then a cross-polarization step with a 2-ms contact time, and, finally, acquisition of the 13C NMR signal under high-power proton decoupling. The delay between the scans was set to 5 s to allow the complete relaxation of the 1H nuclei, and the number of scans ranged between 10,000 and 20,000. An exponential apodization function corresponding to a line broadening of 80 Hz was applied before Fourier transformation. Sample spinning frequencies were 15 and 20 kHz.

Transmission electron microscopy

High-resolution TEM images were obtained using a JEOL JEM3200 FSC operated at 300 kV. Low-resolution TEM images were acquired by a JEOL JEM1400 plus operated at 120 kV. Before TEM observation, the specimens were prepared by applying a few drops of the BILP-101x film ethanol suspensions on a carbon-coated copper grid and letting it dry.

Gas permeation experiments

The supported BILP-101x membranes with an effective area of 1.33 cm2 were mounted in a flange between Viton O-rings. This flange fits in a permeation module, which was placed inside an oven in a homemade permeation setup. The diagram is shown in scheme S1. The H2/CO2 separation measurements were performed using a 50:50 H2/CO2 gas mixture (100 ml min−1 of CO2 and 100 ml min−1 of H2) as feed. Helium (4.6 ml min−1) was used as sweep gas on the permeate side. The absolute pressure of the feed stream was adjusted in a range of 1 to 10 bar using a back-pressure controller at the retentate side, keeping the permeate side at atmospheric pressure. The temperature in the permeation module was adjusted from 298 to 498 K through a convection oven. An online gas chromatograph (Interscience Compact GC) equipped with a packed Carboxen 1010 PLOT (30 m × 0.32 mm) column and a thermal conductivity detector was used to periodically analyze the permeate stream. For single gas permeation tests, there was a 1-bar pressure drop between the feed and permeate side. The typical A3 membrane (table S1) was repeated once to ensure reproducibility of the reported data. In all cases, gas separation performance was evaluated after ensuring steady operation.

Gas separation performance was defined by the selectivity (α) and the gas permeance (P) of the individual components. The permeance of component i (Pi) was calculated as follows (Eq. 1)

| (1) |

where flux Fi denotes the molar flux of compound i (mol m−2 s−1), Ni is the permeate rate of component i (mol s−1), A is the membrane area, and Δpi is the partial pressure difference of component i across the membrane, and it can be calculated according to Eq. 2

| (2) |

where pfeed and pperm represent the pressures at the feed and permeate sides and Yi,feed and Xi,perm are the molar fractions of component i in the feed and permeate gas streams, respectively.

The SI unit for permeance is mol s−1 m−2 Pa−1. However, gas permeances are reported in the widely used unit GPUs, where 1 GPU = 3.3928 × 10−10 mol s−1 m−2 Pa−1.

The separation factor or mixed gas selectivity (α) was calculated as the ratio of the permeance of the faster permeating component (H2) to the permeance of the less permeating component (CO2) (Eq. 3)

| (3) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Chu for helpful discussions and assistance in AFM characterization and A. Bavykina and E. Abou Hamad for assistance with MAS NMR. Funding: B.S. acknowledges the Netherlands National Science Foundation (NWO) for her personal VENI grant. M.S. acknowledges the support from the China Scholarship Council. Author contributions: M.S., X.L., and J.G. conceived the research and designed the experiments. M.S. synthesized the membranes and performed part of the characterization with help from X.L. and X.W. I.Y. performed the NMR analysis. The manuscript was primarily written by M.S., X.L., and J.G. with contributions from all coauthors. Competing interests: M.S., X.L., F.K., and J.G. are inventors on a U.S. Provisional Patent application related to this work, co-owned by Delft University of Technology and King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (application no. 62/659,271, filed on 18 April 2018). The authors declare no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/9/eaau1698/DC1

Scheme S1. Diagram of gas permeation apparatus used in this work.

Fig. S1. Digital photo of the prepared membranes under four different conditions.

Fig. S2. Description of freestanding BILP-101x film synthesis process and resulting films.

Fig. S3. Morphology of the prepared BILP-101x film.

Fig. S4. AFM analysis of the BILP-101x film under A3 conditions.

Fig. S5. Characterization of the BILP-101x film prepared under A3 conditions.

Fig. S6. Effect of the temperature on the membrane separation performance toward H2/CO2.

Fig. S7. Effect of pressure on the membrane performance toward H2/CO2.

Fig. S8. Characterization of the BILP-101x film prepared under A1 and A2 conditions.

Table S1. Summary of membrane preparation conditions.

Table S2. Summary of membrane separation performance tested for H2/CO2.

Table S3. Summary of membrane separation performance tested for H2/N2.

Table S4. Membrane performance of typical PIM, TR polymer, PBI, and BILP presented in Fig. 3A.

Table S5. Membrane performance of some pure COF membranes for H2/N2 separation.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Sholl D. S., Lively R. P., Seven chemical separations to change the world. Nature 532, 435–437 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park H. B., Kamcev J., Robeson L. M., Elimelech M., Freeman B. D., Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 356, eaab0530 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robeson L. M., The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 320, 390–400 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodenas T., Luz I., Prieto G., Seoane B., Miro H., Corma A., Kapteijn F., Llabrés i. Xamena F. X., Gascon J., Metal–organic framework nanosheets in polymer composite materials for gas separation. Nat. Mater. 14, 48–55 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seoane B., Coronas J., Gascon I., Benavides M. E., Karvan O., Caro J., Kapteijn F., Gascon J., Metal–organic framework based mixed matrix membranes: A solution for highly efficient CO2 capture? Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2421–2454 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park H. B., Jung C. H., Lee Y. M., Hill A. J., Pas S. J., Mudie S. T., Van Wagner E., Freeman B. D., Cookson D. J., Polymers with cavities tuned for fast selective transport of small molecules and ions. Science 318, 254–258 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carta M., Malpass-Evans R., Croad M., Rogan Y., Jansen J. C., Bernardo P., Bazzarelli F., McKeown N. B., An efficient polymer molecular sieve for membrane gas separations. Science 339, 303–307 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guiver M. D., Lee Y. M., Polymer rigidity improves microporous membranes. Science 339, 284–285 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu J., Das S., Xing G., Ben T., Valtchev V., Qiu S., Fabrication of COF-MOF composite membranes and their highly selective separation of H2/CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 7673–7680 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X., Tian C., Mahurin S. M., Chai S.-H., Wang C., Brown S., Veith G. M., Luo H., Liu H., Dai S., A superacid-catalyzed synthesis of porous membranes based on triazine frameworks for CO2 separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 10478–10484 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau C. H., Nguyen P. T., Hill M. R., Thornton A. W., Konstas K., Doherty C. M., Mulder R. J., Bourgeois L., Liu A. C. Y., Sprouster D. J., Sullivan J. P., Bastow T. J., Hill A. J., Gin D. L., Noble R. D., Ending aging in super glassy polymer membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5322–5326 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaoui N., Trunk M., Dawson R., Schmidt J., Thomas A., Trends and challenges for microporous polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 3302–3321 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G., Zhang K., Tsuru T., Two-dimensional covalent organic framework (COF) membranes fabricated via the assembly of exfoliated COF nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 8433–8436 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang Z., Peng Y., Qian Y., Yuan D., Addicoat M. A., Heine T., Hu Z., Tee L., Guo Z., Zhao D., Mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) comprising exfoliated 2D covalent organic frameworks (COFs) for efficient CO2 separation. Chem. Mater. 28, 1277–1285 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shan M., Seoane B., Rozhko E., Dikhtiarenko A., Clet G., Kapteijn F., Gascon J., Azine-linked covalent organic framework (COF)-based mixed-matrix membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 14467–14470 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabbani M. G., El-Kaderi H. M., Synthesis and characterization of porous benzimidazole-linked polymers and their performance in small gas storage and selective uptake. Chem. Mater. 24, 1511–1517 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabbani M. G., Reich T. E., Kassab R. M., Jackson K. T., El-Kaderi H. M., High CO2 uptake and selectivity by triptycene-derived benzimidazole-linked polymers. Chem. Commun. 48, 1141–1143 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekizkardes A. K., Culp J. T., Islamoglu T., Marti A., Hopkinson D., Myers C., El-Kaderi H. M., Nulwala H. B., An ultra-microporous organic polymer for high performance carbon dioxide capture and separation. Chem. Commun. 51, 13393–13396 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raaijmakers M. J. T., Hempenius M. A., Schön P. M., Vancso G. J., Nijmeijer A., Wessling M., Benes N. E., Sieving of hot gases by hyper-cross-linked nanoscale-hybrid membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 330–335 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karan S., Jiang Z., Livingston A. G., Sub–10 nm polyamide nanofilms with ultrafast solvent transport for molecular separation. Science 348, 1347–1351 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elimelech M., Phillip W. A., The future of seawater desalination: Energy, technology, and the environment. Science 333, 712–717 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimenez-Solomon M. F., Song Q., Jelfs K. E., Munoz-Ibanez M., Livingston A. G., Polymer nanofilms with enhanced microporosity by interfacial polymerization. Nat. Mater. 15, 760–767 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown A. J., Brunelli N. A., Eum K., Rashidi F., Johnson J. R., Koros W. J., Jones C. W., Nair S., Interfacial microfluidic processing of metal-organic framework hollow fiber membranes. Science 345, 72–75 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ameloot R., Vermoortele F., Vanhove W., Roeffaers M. B. J., Sels B. F., De Vos D. E., Interfacial synthesis of hollow metal–organic framework capsules demonstrating selective permeability. Nat. Chem. 3, 382–387 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dey K., Pal M., Rout K. C., Kunjattu H. S., Das A., Mukherjee R., Kharul U. K., Banerjee R., Selective molecular separation by interfacially crystallized covalent organic framework thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13083–13091 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maaskant E., de Wit P., Benes N. E., Direct interfacial polymerization onto thin ceramic hollow fibers. J. Membr. Sci. 550, 296–301 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabbani M. G., Sekizkardes A. K., El-Kadri O. M., Kaafarani B. R., El-Kaderi H. M., Pyrene-directed growth of nanoporous benzimidazole-linked nanofibers and their application to selective CO2 capture and separation. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 25409–25417 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thommes M., Kaneko K., Neimark A. V., Olivier J. P., Rodriguez-Reinoso F., Rouquerol J., Sing K. S. W., Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1051–1069 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandey P., Katsoulidis A. P., Eryazici I., Wu Y., Kanatzidis M. G., Nguyen S. T., Imine-linked microporous polymer organic frameworks. Chem. Mater. 22, 4974–4979 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang T., Xiao Y., Chung T.-S., Poly-/metal-benzimidazole nano-composite membranes for hydrogen purification. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 4171–4180 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ockwig N. W., Nenoff T. M., Membranes for hydrogen separation. Chem. Rev. 107, 4078–4110 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X., Chi C., Zhang K., Qian Y., Gupta K. M., Kang Z., Jiang J., Zhao D., Reversed thermo-switchable molecular sieving membranes composed of two-dimensional metal-organic nanosheets for gas separation. Nat. Commun. 8, 14460 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng Y., Li Y., Ban Y., Jin H., Jiao W., Liu X., Yang W., Metal-organic framework nanosheets as building blocks for molecular sieving membranes. Science 346, 1356–1359 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H., Song Z., Zhang X., Huang Y., Li S., Mao Y., Ploehn H. J., Bao Y., Yu M., Ultrathin, molecular-sieving graphene oxide membranes for selective hydrogen separation. Science 342, 95–98 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghanem B. S., Swaidan R., Ma X., Litwiller E., Pinnau I., Energy-efficient hydrogen separation by ab-type ladder-polymer molecular sieves. Adv. Mater. 26, 6696–6700 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhuang Y., Seong J. G., Do Y. S., Lee W. H., Lee M. J., Cui Z., Lozano A. E., Guiver M. D., Lee Y. M., Soluble, microporous, Tröger’s Base copolyimides with tunable membrane performance for gas separation. Chem. Commun. 52, 3817–3820 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park H. B., Han S. H., Jung C. H., Lee Y. M., Hill A. J., Thermally rearranged (TR) polymer membranes for CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 359, 11–24 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han S. H., Kwon H. J., Kim K. Y., Seong J. G., Park C. H., Kim S., Doherty C. M., Thornton A. W., Hill A. J., Lozano A. E., Berchtold K. A., Lee Y. M., Tuning microcavities in thermally rearranged polymer membranes for CO2 capture. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 4365–4373 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Do Y. S., Seong J. G., Kim S., Lee J. G., Lee Y. M., Thermally rearranged (TR) poly(benzoxazole-co-amide) membranes for hydrogen separation derived from 3,3′-dihydroxy-4,4′-diamino-biphenyl (HAB), 4,4′-oxydianiline (ODA) and isophthaloyl chloride (IPCl). J. Membr. Sci. 446, 294–302 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pesiri D. R., Jorgensen B., Dye R. C., Thermal optimization of polybenzimidazole meniscus membranes for the separation of hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide. J. Membr. Sci. 218, 11–18 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholes C. A., Smith K. H., Kentish S. E., Stevens G. W., CO2 capture from pre-combustion processes—Strategies for membrane gas separation. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Con. 4, 739–755 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang T., Shi G. M., Chung T.-S., Symmetric and asymmetric zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs)/polybenzimidazole (PBI) nanocomposite membranes for hydrogen purification at high temperatures. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 1358–1367 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sánchez-Laínez J., Zornoza B., Friebe S., Caro J., Cao S., Sabetghadam A., Seoane B., Gascon J., Kapteijn F., Le Guillouzer C., Clet G., Daturi M., Téllez C., Coronas J., Influence of ZIF-8 particle size in the performance of polybenzimidazole mixed matrix membranes for pre-combustion CO2 capture and its validation through interlaboratory test. J. Membr. Sci. 515, 45–53 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumbharkar S. C., Liu Y., Li K., High performance polybenzimidazole based asymmetric hollow fibre membranes for H2/CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 375, 231–240 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu L., Swihart M. T., Lin H., Unprecedented size-sieving ability in polybenzimidazole doped with polyprotic acids for membrane H2/CO2 separation. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 94–100 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindemann P., Tsotsalas M., Shishatskiy S., Abetz V., Krolla-Sidenstein P., Azucena C., Monnereau L., Beyer A., Gölzhäuser A., Mugnaini V., Gliemann H., Bräse S., Wöll C., Preparation of freestanding conjugated microporous polymer nanomembranes for gas separation. Chem. Mater. 26, 7189–7193 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu H., Wang C., Chen J., Ge R., Leng W., Dong B., Huang J., Gao Y., A novel 3D covalent organic framework membrane grown on a porous a-Al2O3 substrate under solvothermal conditions. Chem. Commun. 51, 15562–15565 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/9/eaau1698/DC1

Scheme S1. Diagram of gas permeation apparatus used in this work.

Fig. S1. Digital photo of the prepared membranes under four different conditions.

Fig. S2. Description of freestanding BILP-101x film synthesis process and resulting films.

Fig. S3. Morphology of the prepared BILP-101x film.

Fig. S4. AFM analysis of the BILP-101x film under A3 conditions.

Fig. S5. Characterization of the BILP-101x film prepared under A3 conditions.

Fig. S6. Effect of the temperature on the membrane separation performance toward H2/CO2.

Fig. S7. Effect of pressure on the membrane performance toward H2/CO2.

Fig. S8. Characterization of the BILP-101x film prepared under A1 and A2 conditions.

Table S1. Summary of membrane preparation conditions.

Table S2. Summary of membrane separation performance tested for H2/CO2.

Table S3. Summary of membrane separation performance tested for H2/N2.

Table S4. Membrane performance of typical PIM, TR polymer, PBI, and BILP presented in Fig. 3A.

Table S5. Membrane performance of some pure COF membranes for H2/N2 separation.