Abstract

Iridoid and polyphenol profiles of 30 different honeysuckle berry cultivars and genotypes were studied. Compounds were identified by ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS/MS) in positive and negative ion modes and quantified by HPLC-PDA. The 50 identified compounds included 15 iridoids, 6 anthocyanins, 9 flavonols, 2 flavanonols (dihydroflavonols), 5 flavones, 6 flavan-3-ols, and 7 phenolic acids. 8-epi-Loganic acid, pentosyl-loganic acid, taxifolin 7-O-dihexoside, and taxifolin 7-O-hexoside were identified in honeysuckle berries for the first time. Iridoids and anthocyanins were the major groups of bioactive compounds of honeysuckle constituents. The total content of quantified iridoids and anthocyanins was between 128.42 mg/100 g fresh weight (fw) (‘Dlinnoplodnaya’) and 372 mg/100 g fw (‘Kuvshinovidnaya’) and between 150.04 mg/100 g fw (‘Karina’) and 653.95 mg/100 g fw (‘Amur’), respectively. Among iridoids, loganic acid was the dominant compound, and it represented between 22% and 73% of the total amount of quantified iridoids in honeysuckle berry. A very strong correlation was observed between the antioxidant potential and the quantity of anthocyanins. High content of iridoids in honeysuckle berries can complement antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds.

Keywords: honeysuckle berries, UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS/MS, iridoids, 8-epi-loganic acid, phenolic compounds, taxifolin, cultivars, genotypes, antioxidant activity

1. Introduction

Edible honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea L. var. kamtschatica Sevast.; Caprifoliaceae family) are gaining popularity in many European countries such as Russia, Poland, the Czech Republic, and others. The attractiveness of these fruits derives from a number of factors, including early time of ripening (in Poland before strawberries), resistance to spring frost, flavor, high contents of vitamin C and polyphenol compounds, and health-related properties. The fruits are good plant material for the food industry, for the production of juices, jams, purees, and—for the pharmaceutical industry—for the production of food supplements [1,2,3].

The health benefits of honeysuckle berries have been known and used for a long time in traditional medicine in Russia and China. Current research, both in vitro and in vivo, also supports the traditional medical use of honeysuckle berries. Recent studies indicate, among others, the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties of the extract from honeysuckle berry fruits [4,5,6]. The authors explain the health benefits of honeysuckle berries by the occurrence in the fruit of polyphenol compounds, mainly glycosides of anthocyanins. In addition to the anthocyanins, phenolic acids, flavonols, flavones and flavan-3-ols are also present [3,4,7,8]. Their contents vary in fruits, and depend on many factors, including cultivar and genotypes [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In addition to the polyphenols, in honeysuckle berries iridoids have also been identified [16,17,18,19]. Among the 13 iridoids we have identified epimeric pairs of loganic acid and loganin, sweroside, secologanin, secoxyloganin, and additionally pentosides of loganic acid (two isomers), pentosides of loganin (three isomers), and pentosyl-sweroside [19].

In Russia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Canada, Japan, and other countries, many honeysuckle cultivars have been selected. They differ in the content of bioactive compounds, appearance (size, shape), time of ripening, yield from the bush, growing conditions, and taste. Cultivar diversity is great, because of the search for a cultivar with large and tasty fruits. Honeysuckle berry fruits are sweet and sour, with a somewhat bitter aftertaste, and resemble blackcurrants and blueberries.

In the fruits, sugars affect the degree of sweetness, while organic acids are responsible for the sour taste. The tartness of fruit is determined by the quantity and quality of polyphenols, whereas the bitterness, among other compounds, is determined by secoiridoids [20]. In addition to the fact that polyphenol and iridoid compounds may affect the taste of the fruit, they exhibit high biological activity [21]. Many authors indicate their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [5,22,23,24,25]. Iridoids, in contrast to the polyphenols, are rarely found in fruits. Exceptions include cornelian cherry fruits [26], cranberry [27], bilberry [28], and, recently investigated by us, honeysuckle berries [17,18,19]. In this study, we determined the content of loganic acid, loganin, their three derivatives, and the quantity of iridoids in berries of honeysuckle. There are no publications on the quantitative analysis of different iridoids such as loganin 7-O-pentoside or loganic acid 7-O-pentoside in honeysuckle berries. Therefore, the aim of this study was qualitative and quantitative determination of iridoids and also of polyphenols in berries of 27 cultivars and 3 genotypes of blue honeysuckle (L. caerulea var. kamtschatica) with the usage of chromatographic methods, as well as the determination of their antioxidant activity.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Qualitative Identification of Iridoids and Phenolic Compounds

The results of qualitative identification of the compounds of honeysuckle berries are presented in Table 1, Figures S1 and S2. The compounds were identified by their UPLC retention times, elution order, spectra of the individual peaks (UV/Vis, MS), spectral data and by comparison with literature data. In our research, we determined 50 compounds from two groups: monoterpenes (iridoids) and polyphenols (anthocyanins, flavonols, flavanonols, flavones, flavan-3-ols, phenolic acids).

Table 1.

Characterization of compounds of honeysuckle fruits determined using their spectral characteristics in positive and negative ions in ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS/MS).

| Peak No. | tR (min) | UV λmax (nm) | [M − H]−/[M + H]+ (m/z) | Other Ions (m/z) | Compound | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.45 | 245, 325 | 353.0879 | 191.0553 | 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid | |

| 2 | 2.66 | 242, 278 | 577.1349 | 289.0723/287.0540 | procyanidin dimer | |

| 3 | 2.80 | 245 | 375.1276 | 213.0769/191.0553/151.0771/125.0585 | 8-epi-loganic acid | |

| 4 | 2.98 | 243, 332 | 629.1733 + | 467.1172/449.1063/305.0649/287.0536/137.0236 | taxifolin 7-O-dihexoside | |

| 5 | 3.10 | 242, 278 | 865.1967 | 577.1349/289.0723/287.0540 | procyanidin trimer | |

| 6 | 3.22 | 242, 278 | 289.0723 | 245.0787 | (+)-catechin | |

| 7 | 3.49 | 245, 325 | 341.0849 | 179.0349/135.0440 | caffeoylglucose | |

| 8 | 3.62 | 245, 325 | 353.0879 | 191.0553 | 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid | |

| 9 | 3.73 | 245 | 375.1276 | 213.0769/191.0553/169.0855/151.0771/119.0331 | loganic acid | |

| 10 | 3.89 | 278, 513 | 611.1664 + | 449.1063/287.0536 | cyanidin 3,5-O-diglucoside | |

| 11 | 4.05 | 242, 278 | 577.1349 | 289.0723 | procyanidin dimer | |

| 12 | 4.17 | 245 | 507.1746 | 375.1356/213.0769/169.0855 | pentosyl-loganic acid | |

| 13 | 4.27 | 245 | 375.1276 | 213.0769/195.0678/151.0771/121.0648/119.0331 | 7-epi-loganic acid | |

| 14 | 4.38 | 243, 340 | 467.1172 + | 449.1063/305.0649/287.0536/137.0236 | taxifolin 7-O-hexoside | |

| 15 | 4.49 | 245 | 771.2018 | 609.1432/447.0959/285.0394 | luteolin O-trihexoside | |

| 16 | 4.53 | 245 | 507.1746 | 375.1356/345.0806/213.0769/169.0855/151.0746 | loganic acid 7-O-pentoside | |

| 17 | 4.74 | 280, 514 | 449.1107 + | 287.0536 | cyanidin 3-O-glucoside | |

| 18 | 5.02 | 325 | 353.0880 | 191.0553 | caffeoylquinic acid | |

| 19 | 5.12 | 245 | 507.1700 | 357.1144/327.1092/195.0650/151.0771 | 7-epi-loganic acid 7-O-pentoside | |

| 20 | 5.22 | 242, 278 | 865.1967 | 577.1349/289.0723 | procyanidin trimer | |

| 21 | 5.22 | 280, 517 | 595.1664 + | 287.0536 | cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside | |

| 22 | 5.50 | 242, 278 | 1153.2568 | 865.1967/577.1349/289.0723 | procyanidin tetramer | |

| 23 | 5.61 | 280, 500 | 433.1125 + | 271.0601 | pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside | |

| 24 | 5.68 | 245 | 521.1854 | 389.1423/227.0908 (567.1918 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | pentosyl-loganin | |

| 25 | 5.73 | 245 | 357.1183 | 195.0650/125.0241 (403.1223 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | sweroside | |

| 26 | 5.73 | 245 | 389.1342 | 227.0939/209.0805 (435.1502 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | loganin | |

| 27 | 5.93 | 245 | 489.1630 | 195.0650/125.0241 (535.1502 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | pentosyl-sweroside | |

| 28 | 6.10 | 279, 516 | 463.1247 + | 301.1730 | peonidin 3-O-glucoside | |

| 29 | 6.15 | 245 | 521.1854 | 389.1342/227.0939 (567.1918 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | loganin 7-O-pentoside | |

| 30 | 6.34 | 352 | 625.1386 | 301.0354 | quercetin O-dihexoside | |

| 31 | 6.36 | 278, 519 | 609.1807 + | 301.0730 | peonidin 3-O-rutinoside | |

| 32 | 6.54 | 245 | 389.1342 | 227.0939/209.0805(435.1502 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | 7-epi-loganin | |

| 33 | 6.58 | 245 | 403.1263 | 223.0622/165.0565/121.0288 | secoxyloganin | |

| 34 | 6.74 | 353 | 595.1312 | 301.0354 | quercetin O-vicianoside 1 1 | |

| 35 | 6.78 | 245 | 489.1630 | 389.1342/371.0636/227.0939/209.0805 (567.1918 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | 7-epi-loganin 7-O-pentoside | |

| 36 | 6.87 | 353 | 595.1312 | 301.0354 | quercetin O-vicianoside 2 | |

| 37 | 6.89 | 245 | 433.1331 | 225.0781/155.0347 (433.1331 [M − H + HCOOH]−) | secologanin | |

| 38 | 7.07 | 352 | 609.1483 | 301.0354 | quercetin 3-O-rutinoside | |

| 39 | 7.32 | 352 | 609.1483 | 463.0887/301.0354 | quercetin O-rhamnoside-O-hexoside | |

| 40 | 7.49 | 352 | 463.0887 | 301.0354 | quercetin 3-O-glucoside | |

| 41 | 7.58 | 346 | 593.1507 | 285.0394 | luteolin 7-O-rutinoside | |

| 42 | 7.68 | 346 | 447.0918 | 285.0394 | luteolin 7-O-glucoside | |

| 43 | 7.80 | 352 | 433.0777 | 301.0354 | quercetin O-pentoside | |

| 44 | 8.01 | 346 | 593.1507 | 447.0918/285.0394 | luteolin 7-O-deoxyhexosyl-O-hexoside | |

| 45 | 8.20 | 245, 327 | 609.1483 | 447.0916/315.0512 | isorhamnetin-O-hexosyl-O-pentoside | |

| 46 | 8.39 | 326 | 515.1196 | 353.0879/191.0553 | dicaffeoylquinic acid 1 | |

| 47 | 8.70 | 325 | 515.1196 | 353.0879/191.0553 | dicaffeoylquinic acid 2 | |

| 48 | 8.92 | 352 | 505.0979 | 301.0319 | quercetin O-acetyl-hexoside | |

| 49 | 9.38 | 326 | 515.1196 | 353.0879/191.0553 | dicaffeoylquinic acid 3 | |

| 50 | 9.54 | 339 | 607.1697 | 299.0536/284.0382 | diosmetin 7-O-rutinoside | |

+ positive electrospray ionisation; 1 vicianoside, 6-O-α-l-arabinosyl-d-glucose.

Among the compounds of the first analyzed group, we identified iridoids. In our previous initial studies, we determined thirteen iridoids (loganic acid (LA), loganin (Lo), sweroside (S), their derivatives, and epimeric pairs of LA and Lo) from honeysuckle berries [17,18,19]. In this study, fifteen compounds with typical UV/Vis spectra were discovered. Among them, compounds 3 and 12 were identified in honeysuckle berries for the first time. In the former, higher abundance was observed for the ion at m/z 375.1276 [M − H]− in negative electrospray ionisation (ESI) mode than for the ion at m/z 377.1440 [M + H]+ in positive ESI mode (Figure S3). This compound (tR 2.80 min) displayed the same pseudomolecular and fragment ions as LA (compound 9; tR 3.73 min) and 7-epi-LA (compound 13; tR 4.27 min), but they differed in the retention times and abundance of the major fragment ions. In compound 3, high abundance was observed for ions at m/z 213.0769 [M − 162 − H]−, similarly as in LA, and 197.0802 [M − 162 − 18 + H]+, similarly as in 7-epi-loganic acid (7-epi-LA) (Figure S3). In the previous study, we showed that for 7-epi-LA, ion [M − 162 − H]− was less stable in negative ESI mode, when the –OH group in C-7 is below the molecule plane; therefore the ion appears after loss of water [M – 162 − 18 − H]− [19]. It is similar in the case of 8-epi-loganic acid (8-epi-LA) in positive ESI mode. Ion [M − 162 + H]+ is less stable when the –CH3 group in C-8 is below the molecule plane; therefore the ion appears after loss of water [M − 162 − 18 + H]+. There are no reports about the contents of this compound in other fruits. 8-epi-LA and its derivatives were isolated only from green plants [29,30]. The second newly identified iridoid was compound 12. In negative mode, this compound had a pseudomolecular ion at m/z 507.1746 [M − H]− and fragment ions at m/z 375.1356 [M − 132 − H]−, 213.0769 [M − 132 − 162 − H]−, and 169.0855 [M − 132 − 162 − 44 − H]−. So this was identified tentatively as a pentose derivative of loganic acid. Similarly to pentosyl-loganin (pLo) [19], this compound did not show ions [M − 162 − H]− and [M − 162 − 18 − H]−. According to these data, in compound 12, pentose is attached to glucose, producing a disaccharide similar to compound 24. It seems that this is pentosyl-loganic acid (pLA) (12).

Among the compounds of the second determined group (polyphenols), we identified basic anthocyanins, flavonols, flavanonols (dihydroflavonols), flavones, flavan-3-ols, and phenolic acids. Six anthocyanins were identified in positive mode. Compounds 10, 17, and 21 exhibited pseudomolecular ions [M + H]+ at m/z 611.1664, 449.1107, and 595.1664 and a similar fragment ion at m/z 287.0536, which corresponded to the molecule of the cyanidin aglycone, after loss of a diglucose, glucose, and rutinose, respectively. Compound 23 gave a fragment ion at m/z 271.0601 after loss of 162 Da, which corresponded to the pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside (Pg 3-glc), whereas compounds 28 and 31 showed a fragment ion at m/z 301.1730 after loss of 162 and 308 Da, which corresponded to the peonidin 3-O-glucoside (Pn 3-glc) and peonidin 3-O-rutinoside (Pn 3-rut), respectively. These results agreed with recently published data [3,4].

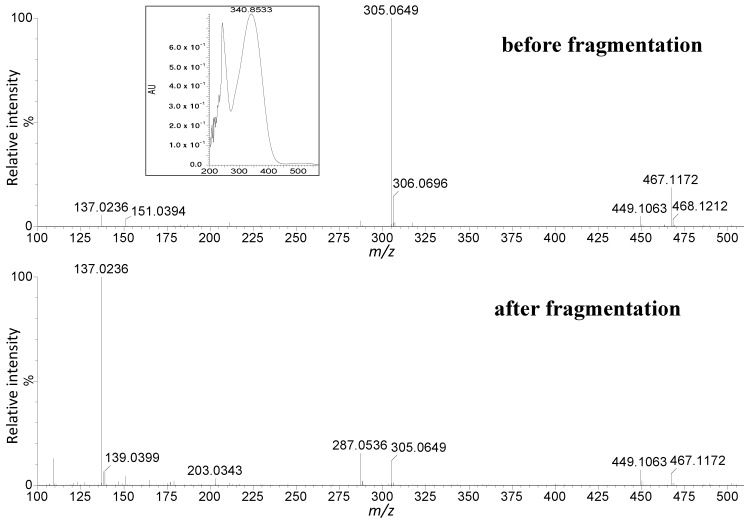

Among the nine flavonols, there were seven derivatives of quercetin (compounds 30, 34, 36, 38, 39, 40, 43, 48) with an aglycone ion at m/z 301.0354 and isorhamnetin (compound 45) with an aglycone ion at m/z 315.0512. In this study, one compound (30) at m/z 625.1386 [M − H]−, two compounds (34, 36) at m/z 595.1312 [M − H]−, two compounds (38, 39) at m/z 609.1483 [M − H]−, one compound (40) at m/z 463.0887 [M − H]−, and one compound (48) at m/z 505.0979 [M − H]− were found. Compound 45 has pseudomolecular ions at m/z 609.1483 [M − H]− and 447.0916 [M − 162 − H]−, which corresponded to isorhamnetin hexosyl-pentoside. These results are consistent with previous studies [3]. Besides flavonols, we identified in honeysuckle berries also two flavanonols (dihydroflavonols) for the first time. Their UV/Vis and mass spectra in positive mode are shown in Figure 1. Compounds 4 and 14 exhibited pseudomolecular ions [M + H]+ at m/z 629.1733 and 467.1173, respectively. They have similar fragment ions at m/z 305.0649 and 287.0536, which correspond to the aglycone of taxifolin and taxifolin after the water loss [Aglycone − 18 + H]+. In the positive mode both taxifolin glycosides beside pseudomolecular ions [M + H]+ at 629.1733 and 468.1172 provided additional ions at 611.1614 and 449.1063 corresponding to structures about 18 Da smaller [M − 18 + H]+ after the loss of water. This observation confirms that compounds 4 and 14 have free –OH at the C-3 position, and they are probably taxifolin 7-O-dihexoside (4) and 7-O-hexoside (14), respectively. The most probable structures of fragment ions of taxifolin derivatives in positive mode are shown in Figure S4 and Table S1. Flavanonols have been detected for example in Rosa canina and R. micrantha fruits [31] but not in blue honeysuckle berries.

Figure 1.

Mass spectra of the ions of taxifolin 7-O-hexoside in positive mode before and after fragmentation and UV/Vis spectra.

Five compounds belonging to flavones were also detected. They were four derivatives of luteolin (compounds 15, 41, 42, 44) with an aglycone ion at m/z 285.0394 [M − H]− and diosmetin (compound 50) with an aglycone ion at m/z 299.0536 [M − H]−. In previous studies Oszmiański et al. [3] identified four derivatives of luteolin. Compound 15 (tR 4.44 min) had a pseudomolecular ion at m/z 771.2018 [M − H]− and fragment ions at m/z 609.1432 [M − 162 − H]−, 447.0959 [M − 162 − 162 − H]−, and 285.0394 [M − 162 − 162 − 162 − H]−. It was identified tentatively as luteolin trihexoside. Compounds 41 and 44 gave the same pseudomolecular ion at m/z 593.1507 [M − H]− but they were different in the retention time. Compounds 41 and 44 had two fragment ions at m/z 447.0918 [M − 146 − H]− and 285.0394 [M − 146 − 162 − H]−. These compounds are luteolin 7-O-rutinoside and luteolin O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside, which is consistent with earlier studies [3]. Compound 42 was identified as luteolin 7-O-glucoside, with a pseudomolecular ion at m/z 447.0918 and a fragment ion at 285.0394 obtained after the loss of 162 Da, which has been confirmed by other authors [3,7] and compared with data for the proper standard. Compound 50 was identified as 7-O-rutinoside of diosmetin (diosmin) when compared with the standard.

Among the flavan-3-ols, we identified six compounds: (+)-catechin (6) and five oligomeric procyanidins type B—two PC dimers (2, 11), two PC trimers (5, 20), and a PC tetramer (22), which had characteristic pseudomolecular (compound 6), or fragment (compounds 2, 5, 11, 20, 22) ions at m/z 289.0723 and others [32]. Oszmiański et al. [3], in addition to these compounds, also identified (–)-epicatechin. Seven phenolic acids including three caffeoylquinic acids (compounds 1, 8, 18) with a fragment ion at m/z 191.0553, three dicaffeoylquinic acids (compounds 46, 47, 49) with fragment ions at m/z 353.0879 and 191.0553 and one caffeoylglucose (compound 7) with a fragment ion at m/z 179.0349, were identified, which was consistent with the data reported by other authors [3].

2.2. Quantitative Identification of Iridoids and Phenolic Compounds

Fifty compounds from the iridoid and polyphenolic groups were identified with the UPLC-qTOF-MS/MS method (Table 1), but only major compounds were quantified using HPLC-PDA detection (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7). Quantitative analysis of constituents of honeysuckle berry was performed for 27 cultivars and 3 genotypes.

Table 2.

Iridoid content (mg/100 g fw) of different blue honeysuckle cultivars and genotypes.

| Cultivar/genotype | LA | 7-epi-LA | LAp | 7-epi-LAp | S+Lo | Lop | 7-epi-Lop | secoLo | Total Ir |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Amphora’ | 60.44 ± 1.07no1 | 44.74 ± 0.44e | 12.22 ± 0.90f | 25.82 ± 2.10g | 83.85 ± 1.02a | 4.91 ± 0.34gh | 231.98d | ||

| ‘Amur’ | 136.85 ± 4.12c | 36.67 ± 1.11g | 9.78 ± 0.23gh | 19.64 ± 3.06i | 45.83 ± 2.34e | 3.52 ± 0.06c | 7.61 ± 0.37e | 259.89b | |

| ‘Atut’ | 63.29 ± 1.24n | 16.71 ± 0.52m | 3.35 ± 0.07k | 22.04 ± 2.15hi | 70.29 ± 1.49b | 6.62 ± 0.05b | 11.84 ± 0.26bc | 194.13h | |

| ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’ 1 | 90.18 ± 2.20i | 2.86 ± 0.30k | 50.01 ± 2.62c | 3.51 ± 0.19c | 6.20 ± 0.18f | 152.77kl | |||

| ‘Berry Smart Blue’ | 126.48 ± 0.48e | 21.63 ± 0.14d | 31.22 ± 0.88h | 17.29 ± 0.55cd | 24.56 ± 0.79gh | 40.74 ± 0.52f | 2.75 ± 0.31de | 11.77 ± 0.06bc | 276.43a |

| ‘Blue Velvet’ | 51.12 ± 2.71r | 9.37 ± 0.16o | 15.03 ± 1.62e | 7.34 ± 0.15lmn | 47.27 ± 0.52de | 9.11 ± 0.35a | 5.05 ± 0.12gh | 144.29mn | |

| ‘Chelyabinka’ | 39.21 ± 0.50wz | 23.36 ± 0.77c | 19.25 ± 0.60l | 6.18 ± 0.09j | 4.22 ± 0.16nop | 32.43 ± 1.55gh | 124.67o | ||

| ‘Chernichka’ | 57.70 ± 0.81op | 2.45 ± 0.13g | 28.28 ± 0.15i | 13.50 ± 0.88ef | 3.80 ± 0.50op | 12.11 ± 0.21m | 1.83 ± 0.11f | 3.77 ± 0.14i | 123.46o |

| ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’ | 41.44 ± 0.69tw | 1.79 ± 0.09g | 37.39 ± 0.17g | 10.64 ± 0.03g | 3.46 ± 0.23op | 25.24 ± 0.59k | 119.95o | ||

| ‘Fialka’ | 56.52 ± 0.11op | 13.23 ± 1.10n | 14.13 ± 0.23e | 40.94 ± 4.45e | 70.34 ± 0.38b | 2.32 ± 0.30def | 11.20 ± 0.91c | 208.71f | |

| ‘Goluboe Vereteno’ | 118.46 ± 3.52f | 26.28 ± 0.38b | 13.81 ± 0.34e | 32.83 ± 1.62f | 2.60 ± 0.14de | 3.49 ± 0.96i | 197.47gh | ||

| ‘Jolanta’ | 55.11 ± 1.12pr | 10.37 ± 1.06e | 28.94 ± 0.13i | 9.59 ± 0.00gh | 4.12 ± 0.02nop | 25.75 ± 0.11k | 5.24 ± 0.05g | 139.13n | |

| ‘Kamchadalka’ | 67.74 ± 2.57m | 71.16 ± 0.48a | 10.13 ± 0.85gh | 6.48 ± 0.37mno | 33.81 ± 0.41g | 2.15 ± 0.11ef | 12.15 ± 0.34b | 203.61fg | |

| ‘Karina’ | 116.17 ± 1.17f | 18.44 ± 0.42bc | 68.27 ± 2.16b | 3.68 ± 0.07c | 9.55 ± 0.11d | 216.11e | |||

| ‘Klon 38’ | 46.64 ± 1.17s | 10.54 ± 0.22e | 22.63 ± 0.46k | 8.58 ± 0.66hi | 3.57 ± 0.49op | 26.70 ± 0.69jk | 4.87 ± 0.09gh | 123.53o | |

| ‘Klon 40’ | 76.72 ± 1.39k | 8.48 ± 1.44f | 61.88 ± 1.74b | 10.71 ± 0.74g | 6.64 ± 0.23mno | 40.08 ± 0.10f | 0.88 ± 0.04j | 205.40f | |

| ‘Klon 44’ | 69.76 ± 0.83m | 13.72 ± 1.92n | 9.42 ± 0.01gh | 12.54 ± 0.30jk | 49.44 ± 2.06d | 3.81 ± 0.04c | 13.30 ± 0.57a | 171.98i | |

| ‘Krupnoplodnaya’ | 106.94 ± 0.18g | 22.62 ± 1.08k | 17.47 ± 0.34cd | 4.76 ± 0.61nop | 25.58 ± 0.36k | 1.30 ± 0.28j | 178.67i | ||

| ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’ | 182.28 ± 2.64a | 19.26 ± 0.47ab | 45.68 ± 0.31d | 247.21c | |||||

| ‘Leningradskii V.’ | 131.69 ± 0.84d | 47.40 ± 0.13d | 15.01 ± 0.72e | 3.36 ± 0.64op | 19.22 ± 0.76l | 0.88 ± 0.01j | 217.57e | ||

| ‘Morena’ | 161.36 ± 5.85b | 35.76 ± 0.36g | 20.43 ± 1.46a | 8.75 ± 0.10lm | 38.87 ± 2.68f | 7.47 ± 0.96e | 272.63a | ||

| ‘Nympha’ | 71.35 ± 1.68lm | 26.23 ± 0.22j | 9.75 ± 0.33gh | 14.25 ± 2.81j | 32.71 ± 0.42g | 4.17 ± 0.19hi | 158.46jk | ||

| ‘Roksana’ | 58.15 ± 0.58op | 49.49 ± 0.22c | 6.75 ± 0.77j | 10.56 ± 0.01kl | 21.30 ± 0.25l | 3.76 ± 0.59i | 150.01lm | ||

| ‘Sineglazka’ | 38.49 ± 0.51wz | 24.12 ± 0.40c | 19.45 ± 0.29l | 6.68 ± 0.22j | 4.91 ± 0.01nop | 29.01 ± 0.39ij | 122.66o | ||

| ‘Tomichka’ | 84.92 ± 2.04j | 20.09 ± 0.25l | 7.36 ± 1.55ij | 1.87 ± 0.32p | 10.87 ± 0.12m | 125.10o | |||

| ‘Vasilevskaya’ | 74.04 ± 0.55kl | 24.90 ± 1.14j | 17.87 ± 0.66bcd | 18.89 ± 0.72i | 29.98 ± 0.02hi | 2.80 ± 0.24d | 9.42 ± 0.10d | 177.90i | |

| ‘Viola’ | 45.48 ± 2.35st | 45.05 ± 0.62a | 40.57 ± 1.16f | 3.69 ± 0.02k | 9.61 ± 0.23klm | 5.85 ± 0.85n | 150.25lm | ||

| ‘Volshebnica’ | 68.84 ± 0.65m | 19.97 ± 0.80l | 14.58 ± 0.44e | 20.45 ± 0.94i | 20.94 ± 0.43l | 4.01 ± 0.63c | 13.29 ± 0.01a | 162.07j | |

| ‘Vostorg’ | 35.22 ± 2.35z | 50.32 ± 1.81c | 9.81 ± 0.67gh | 56.59 ± 3.40c | 9.30 ± 0.86 | 161.24j | |||

| ‘Wojtek’ | 100.13 ± 1.19h | 16.58 ± 0.84d | 71.71 ± 0.18a | 4.02 ± 0.29c | 13.30 ± 0.06a | 205.74f |

LA, loganic acid; 7-epi-LA, 7-epi loganic acid; LAp, loganic acid 7-O-pentoside; 7-epi-LAp, 7-epi-loganic acid 7-O-pentoside; S, sweroside; Lo, loganin; Lop, loganin 7-O-pentoside; secoLo, secologanin; Total Ir, total amount of quantified iridoids; 1 ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’, ‘Bakcharskaya Yubileynaya’; ‘Leningradskii V.’, ‘Leningradskii Velikan’. 1 Values are expressed as the mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c, etc.) within the same column are statistically different (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Anthocyanin content (mg/100 g fw) of different blue honeysuckle cultivars and genotypes.

| Cultivar/Genotype | Cy 3,5-diglc | Cy 3-glc | Cy 3-rut | Pg 3-glc | Pn 3-glc | Pn 3-rut | Total A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Amphora’ | 27.42 ± 0.65b 1 | 400.11 ± 14.67de | 27.68 ± 0.10a | 2.18 ± 0.07e | 12.25 ± 0.38g | 1.69 ± 0.07de | 471.32d |

| ‘Amur’ | 32.10 ± 1.02a | 577.19 ± 20.46a | 14.38 ± 0.04g | 9.02 ± 0.29a | 21.26 ± 0.71b | 1.25 ± 0.01f | 655.21a |

| ‘Atut’ | 11.57 ± 0.64j | 163.19 ± 8.17no | 1.83 ± 0.11rs | 0.44 ± 0.05lmn | 5.20 ± 0.27p | 0.15 ± 0.03n | 182.37o |

| ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’ 2 | 5.24 ± 0.07pr | 217.02 ± 2.57jkl | 4.92 ± 0.09o | 4.76 ± 0.01b | 5.43 ± 0.10op | 0.36 ± 0.00kl | 237.73klm |

| ‘Berry Smart Blue’ | 11.28 ± 0.42j | 239.44 ± 15.97hi | 24.66 ± 0.29c | 1.02 ± 0.05i | 10.39 ± 0.63h | 1.85 ± 0.06c | 288.63hi |

| ‘Blue Velvet’ | 11.29 ± 0.14j | 216.04 ± 1.79jkl | 2.65 ± 0.06pr | 0.47 ± 0.02lm | 5.52 ± 0.02op | 0.30 ± 0.01lm | 236.26klm |

| ‘Chelyabinka’ | 16.59 ± 0.21fg | 280.73 ± 2.56g | 6.44 ± 0.14klm | 1.32 ± 0.05g | 9.84 ± 0.11hi | 0.55 ± 0.01j | 315.46fg |

| ‘Chernichka’ | 6.43 ± 0.01no | 179.66 ± 1.15mn | 6.82 ± 0.03k | 0.39 ± 0.03mn | 5.91 ± 0.04nop | 0.43 ± 0.00k | 199.64no |

| ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’ | 15.94 ± 0.11g | 290.68 ± 2.60g | 14.51 ± 0.10g | 3.52 ± 0.05c | 8.36 ± 0.02kl | 0.63 ± 0.01ij | 333.65f |

| ‘Fialka’ | 18.24 ± 0.11e | 387.53 ± 0.47ef | 9.82 ± 1.60ij | 1.28 ± 0.07g | 14.54 ± 0.05e | 1.12 ± 0.02g | 432.54e |

| ‘Goluboe Vereteno’ | 9.43 ± 0.12k | 245.44 ± 10.20gh | 7.26 ± 0.13k | 0.58 ± 0.04kl | 10.47 ± 0.35h | 0.64 ± 0.02ij | 273.82ij |

| ‘Jolanta’ | 20.40 ± 0.52d | 511.40 ± 25.23b | 11.74 ± 0.92h | 2.18 ± 0.10e | 12.98 ± 0.51f | 0.30 ± 0.00lm | 559.02c |

| ‘Kamchadalka’ | 3.64 ± 0.10s | 204.41 ± 5.73jkl | 10.27 ± 0.09i | 0.21 ± 0.01o | 5.50 ± 0.14op | 0.58 ± 0.01j | 224.61lm |

| ‘Karina’ | 5.20 ± 0.08pr | 135.41 ± 2.76p | 7.36 ± 0.32k | 0.30 ± 0.00no | 1.77 ± 0.10t | 0.27 ± 0.00m | 150.31p |

| ‘Klon 38’ | 6.57 ± 0.05n | 234.71 ± 8.75hi | 5.18 ± 0.17no | 0.80 ± 0.02j | 5.55 ± 0.25op | 0.32 ± 0.00lm | 253.13jk |

| ‘Klon 40’ | 20.94 ± 0.17d | 560.76 ± 6.58a | 14.82 ± 0.02g | 2.57 ± 0.01d | 14.45 ± 0.21e | 1.19 ± 0.03fg | 614.72b |

| ‘Klon 44’ | 14.88 ± 0.69h | 222.40 ± 19.41ij | 1.94 ± 0.13rs | 0.70 ± 0.01jk | 8.47 ± 0.68jkl | 0.16 ± 0.02n | 248.54kl |

| ‘Krupnoplodnaya’ | 3.49 ± 0.07s | 155.85 ± 2.34op | 5.89 ± 0.03lmn | 0.47 ± 0.02lm | 9.16 ± 0.15ij | 0.74 ± 0.00h | 175.60o |

| ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’ | 14.89 ± 0.53h | 422.28 ± 15.91c | 17.60 ± 0.66e | 1.09 ± 0.05hi | 23.35 ± 0.85a | 2.09 ± 0.05b | 481.30d |

| ‘Leningradskii V.’ | 5.61 ± 0.08p | 197.88 ± 0.31lm | 6.70 ± 0.13kl | 0.74 ± 0.02j | 8.64 ± 0.02jk | 0.70 ± 0.01hi | 220.27mn |

| ‘Morena’ | 22.27 ± 0.37c | 409.92 ± 1.41cd | 22.34 ± 0.03d | 3.48 ± 0.02c | 14.08 ± 0.06e | 1.62 ± 0.14e | 473.71d |

| ‘Nympha’ | 13.03 ± 0.03i | 496.30 ± 0.05b | 26.65 ± 0.14b | 1.49 ± 0.00f | 18.46 ± 0.07c | 1.74 ± 0.07d | 557.68c |

| ‘Roksana’ | 5.68 ± 0.12p | 181.93 ± 3.68mn | 3.23 ± 0.11p | 0.22 ± 0.01o | 5.99 ± 0.19no | 0.25 ± 0.02m | 197.31o |

| ‘Sineglazka’ | 16.93 ± 0.13f | 272.89 ± 1.47g | 5.64 ± 0.17mno | 1.10 ± 0.00hi | 9.21 ± 0.05ij | 0.57 ± 0.03j | 306.33gh |

| ‘Tomichka’ | 4.54 ± 0.07pr | 175.66 ± 1.67no | 9.22 ± 0.09j | 1.23 ± 0.02gh | 4.40 ± 0.06r | 0.43 ± 0.00k | 195.49o |

| ‘Vasilevskaya’ | 7.38 ± 0.10m | 200.04 ± 0.72klm | 6.88 ± 0.15k | 2.05 ± 0.01e | 7.89 ± 0.01lm | 0.55 ± 0.02j | 224.79lm |

| ‘Viola’ | 5.81 ± 0.10op | 136.37 ± 4.42p | 1.47 ± 0.03s | 1.46 ± 0.09f | 6.50 ± 0.20n | 0.13 ± 0.00n | 151.74p |

| ‘Volshebnica’ | 8.02 ± 0.10lm | 221.09 ± 4.05ijk | 5.90 ± 0.06lmn | 0.36 ± 0.01mno | 7.58 ± 0.16m | 0.62 ± 0.01ij | 243.57klm |

| ‘Vostorg’ | 8.63 ± 0.40l | 368.23 ± 13.66f | 27.94 ± 1.16a | 0.55 ± 0.03l | 15.30 ± 0.64d | 2.22 ± 0.09a | 422.87e |

| ‘Wojtek’ | 10.90 ± 0.02j | 251.00 ± 4.83h | 15.67 ± 0.08f | 0.81 ± 0.00j | 2.98 ± 0.04s | 0.30 ± 0.01m | 281.66i |

Cy 3,5-diglc, cyanidin 3,5-O-diglucoside; Cy 3-glc, cyanidin 3-O-glucoside; Cy 3-rut, cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside; Pg 3-glc, pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside; Pn 3-glc, peonidin 3-O-glucoside; Pn 3-rut, peonidin 3-O-rutinoside; Total A, total amount of quantified anthocyanins; 1 Values are expressed as the mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c, etc.) within the same column are statistically different (p < 0.05). 2 ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’, ‘Bakcharskaya Yubileynaya’; ‘Leningradskii V.’, ‘Leningradskii Velikan’.

Table 4.

Flavonol, flavanonol, and flavanone contents (mg/100 g fw) of different blue honeysuckle cultivars and genotypes.

| Cultivar/Genotype | Q-vic | Q-rha-hex | Q 3-glc | Total Q | Tx 7-hex | L-trihex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Amphora’ | 1.54 ± 0.10p1 | 14.44 ± 0.42g | 6.42 ± 0.10e | 22.40g | 8.57 ± 0.22f | 0.80 ± 0.05c |

| ‘Amur’ | 2.76 ± 0.14n | 24.10 ± 0.63a | 7.06 ± 0.63d | 33.92b | 13.83 ± 0.42b | 0.54 ± 0.01e |

| ‘Atut’ | 4.26 ± 0.21kl | 14.12 ± 0.67gh | 7.88 ± 0.33c | 26.27e | 4.06 ± 0.22lm | 0.26 ± 0.02jkl |

| ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’ 2 | 8.60 ± 0.51e | 2.44 ± 0.15t | 3.18 ± 0.19lm | 14.22kl | 6.64 ± 0.10gh | |

| ‘Berry Smart Blue’ | 1.03 ± 0.04r | 13.66 ± 0.33hi | 1.60 ± 0.04p | 16.29ij | 6.36 ± 0.36ghi | 0.25 ± 0.01jkl |

| ‘Blue Velvet’ | 3.29 ± 0.04m | 5.08 ± 0.01r | 4.19 ± 0.05ijk | 12.56m | 6.94 ± 0.23g | 0.19 ± 0.01klm |

| ‘Chelyabinka’ | 7.94 ± 0.03f | 12.65 ± 0.28j | 3.81 ± 0.09k | 24.39f | 6.31 ± 0.06ghi | 0.26 ± 0.00jkl |

| ‘Chernichka’ | 1.77 ± 0.13op | 12.39 ± 0.33jk | 1.40 ± 0.09p | 15.55ij | 4.74 ± 0.15kl | 0.30 ± 0.00ij |

| ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’ | 2.56 ± 0.12n | 17.81 ± 0.19d | 2.06 ± 0.05o | 22.44g | 6.62 ± 0.16gh | 0.30 ± 0.02ij |

| ‘Fialka’ | 1.91 ± 0.02o | 15.75 ± 0.06f | 4.33 ± 0.21ij | 21.99g | 9.78 ± 0.11e | 0.43 ± 0.01fg |

| ‘Goluboe Vereteno’ | 1.79 ± 0.05op | 11.48 ± 0.29l | 3.15 ± 0.33lm | 16.42i | 6.38 ± 0.45ghi | 0.35 ± 0.02hi |

| ‘Jolanta’ | 8.31 ± 0.15e | 12.43 ± 0.19jk | 8.36 ± 0.26b | 29.10d | 11.83 ± 0.05c | 0.32 ± 0.10hij |

| ‘Kamchadalka’ | 10.19 ± 0.24ab | 7.98 ± 0.15o | 4.00 ± 0.13jk | 22.17g | 5.93 ± 0.02hij | 0.26 ± 0.01jk |

| ‘Karina’ | 1.04 ± 0.02r | 9.55 ± 0.25n | 1.41 ± 0.04p | 12.00m | 3.22 ± 0.07no | 0.38 ± 0.00gh |

| ‘Klon 38’ | 9.89 ± 0.04bc | 13.31 ± 0.19i | 6.04 ± 0.13e | 29.24d | 5.90 ± 0.15hij | 0.11 ± 0.01n |

| ‘Klon 40’ | 10.40 ± 0.16a | 15.97 ± 0.33f | 9.09 ± 0.10a | 35.46a | 11.32 ± 0.60cd | 0.38 ± 0.01gh |

| ‘Klon 44’ | 4.60 ± 0.26j | 4.02 ± 0.28s | 5.47 ± 0.40f | 14.10kl | 5.78 ± 0.38ij | 0.09 ± 0.01n |

| ‘Krupnoplodnaya’ | 6.59 ± 0.05h | 6.38 ± 0.04p | 2.76 ± 0.07mn | 15.73ij | 4.44 ± 0.10l | 0.12 ± 0.01n |

| ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’ | 3.95 ± 0.07l | 11.91 ± 0.30kl | 4.58 ± 0.09hi | 20.44h | 11.02 ± 0.62d | 0.95 ± 0.05b |

| ‘Leningradskii V.’ | 7.74 ± 0.03f | 8.30 ± 0.01o | 4.20 ± 0.09ijk | 20.25h | 5.84 ± 0.19hij | 0.37 ± 0.01gh |

| ‘Morena‘ | 7.27 ± 0.02g | 18.92 ± 0.32c | 4.15 ± 0.01ijk | 30.34d | 11.25 ± 0.73cd | 1.07 ± 0.02a |

| ‘Nympha’ | 2.60 ± 0.07n | 24.21 ± 0.03a | 4.97 ± 0.22gh | 31.79c | 14.56 ± 0.28a | 0.63 ± 0.03d |

| ‘Roksana’ | 6.12 ± 0.13i | 1.50 ± 0.03w | 3.03 ± 0.12lmn | 10.65n | 5.33 ± 0.02jk | |

| ‘Sineglazka’ | 6.81 ± 0.01h | 10.29 ± 0.30m | 3.36 ± 0.21l | 20.47h | 6.41 ± 0.06ghi | 0.19±0.02m |

| ‘Tomichka’ | 0.81 ± 0.01s | 21.29 ± 0.08b | 1.28 ± 0.10p | 22.57g | 3.70 ± 0.20mn | 0.20±0.04klm |

| ‘Vasilevskaya’ | 9.28 ± 0.05d | 10.32 ± 0.10m | 4.83 ± 0.10gh | 24.43f | 5.76 ± 0.09ij | 0.46 ± 0.00f |

| ‘Viola’ | 9.82 ± 0.22c | 9.59 ± 0.21n | 5.22 ± 0.09fg | 24.62f | 2.80 ± 0.10o | 0.27 ± 0.01j |

| ‘Volshebnica’ | 4.39 ± 0.05jk | 7.99 ± 0.14o | 2.65 ± 0.04n | 15.03jk | 5.78 ± 0.13ij | 0.37 ± 0.02ghi |

| ‘Vostorg’ | 6.03 ± 0.38i | 16.97 ± 0.86e | 2.05 ± 0.06o | 25.47ef | 5.88 ± 1.01nij | 0.42 ± 0.02fg |

| ‘Wojtek’ | 1.14 ± 0.03r | 10.57 ± 0.05m | 1.45 ± 0.04p | 13.16lm | 5.38 ± 0.06jk | 0.63 ± 0.04d |

Q-vic, quercetin O-vicianoside 1; Q-rha-hex, quercetin O-rhamnoside-O-hexoside; Q 3-glc, quercetin 3-O-glucoside; Total Q, total amount of quantified derivatives of quercetin; Tx 7-hex, taxifolin 3-O-hexoside; L-trihex, luteolin trihexoside; 1 Values are expressed as the mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c, etc.) within the same column are statistically different (p < 0.05). 2 ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’, ‘Bakcharskaya Yubileynaya’; ‘Leningradskii V.’, ‘Leningradskii Velikan’.

Table 5.

Flavan-3-ol derivatives content (mg/100 g fw) of different blue honeysuckle cultivars and genotypes.

| Cultivar/Genotype | PC Dimer 1 | (+)-Catechin | PC Dimer 2 | Total F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Amphora’ | 7.93 ± 0.64h 1 | 10.52 ± 1.02h | 7.80 ± 0.29fg | 26.26ij |

| ‘Amur’ | 11.91 ± 0.24d | 12.46 ± 0.47fg | 4.37 ± 0.07j | 28.74h |

| ‘Atut’ | 3.08 ± 0.45r | 4.31 ± 0.29no | 5.43 ± 0.48hi | 12.82m |

| ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’ 2 | 6.01 ± 0.28jklm | 9.14 ± 0.02i | 12.39 ± 0.33d | 27.54hi |

| ‘Berry Smart Blue’ | 11.37 ± 0.41de | 17.15 ± 0.59d | 28.52h | |

| ‘Blue Velvet’ | 0.89 ± 0.04s | 2.14 ± 0.03r | 1.55 ± 0.01l | 4.58o |

| ‘Chelyabinka’ | 14.87 ± 0.13b | 17.22 ± 0.04d | 20.95 ± 0.61a | 53.04b |

| ‘Chernichka’ | 5.57 ± 0.08lmn | 7.11 ± 0.06j | 12.33 ± 0.57d | 25.00j |

| ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’ | 18.38 ± 0.77a | 31.22 ± 0.44a | 5.76 ± 0.23h | 55.36a |

| ‘Fialka’ | 5.63 ± 1.19lmn | 6.10 ± 0.58kl | 9.37 ± 0.34e | 21.10k |

| ‘Goluboe Vereteno’ | 13.08 ± 0.10c | 23.05 ± 0.01b | 36.12f | |

| ‘Jolanta’ | 12.04 ± 0.08d | 4.23 ± 0.32no | 4.62 ± 0.29ij | 20.89k |

| ‘Kamchadalka’ | 4.68 ± 0.19op | 11.75 ± 0.27g | 14.85 ± 0.36c | 31.28g |

| ‘Karina’ | 10.48 ± 0.02f | 15.80 ± 0.56e | 2.76 ± 0.10k | 29.05h |

| ‘Klon 38’ | 5.29 ± 0.08mno | 6.61 ± 0.10jk | 8.63 ± 0.09ef | 20.53k |

| ‘Klon 40’ | 9.58 ± 0.29g | 5.48 ± 0.18lm | 4.72 ± 0.11ij | 19.77kl |

| ‘Klon 44’ | 3.30 ± 0.47r | 2.84 ± 0.36pr | 7.38 ± 0.29g | 13.52m |

| ‘Krupnoplodnaya’ | 6.54 ± 0.10ijk | 3.32 ± 0.03op | 16.05 ± 0.02b | 25.91ij |

| ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’ | 3.27 ± 0.13r | 2.04 ± 0.31r | 3.90 ± 0.64j | 9.21n |

| ‘Leningradskii V.’ | 4.04 ± 0.08p | 4.46 ± 0.10n | 16.13 ± 0.07b | 24.63j |

| ‘Morena‘ | 5.86 ± 0.08klm | 9.69 ± 0.33hi | 9.01 ± 0.20e | 24.56j |

| ‘Nympha’ | 4.85 ± 0.07no | 4.91 ± 0.37mn | 8.58 ± 0.32ef | 18.34l |

| ‘Roksana’ | 6.80 ± 0.18ij | 10.67 ± 0.90h | 21.77 ± 1.09a | 39.24e |

| ‘Sineglazka’ | 14.91 ± 0.04b | 17.71 ± 0.44d | 15.10 ± 0.30c | 47.72d |

| ‘Tomichka’ | 10.88 ± 0.16ef | 17.55 ± 0.65d | 28.43h | |

| ‘Vasilevskaya’ | 9.34 ± 0.71g | 19.85 ± 1.27c | 21.53 ± 0.83a | 50.72c |

| ‘Viola’ | 1.62 ± 0.04s | 10.02 ± 0.11hi | 20.92 ± 0.08a | 32.55g |

| ‘Volshebnica’ | 6.13 ± 0.12ijkl | 9.86 ± 0.04hi | 12.66 ± 0.36d | 28.66h |

| ‘Vostorg’ | 6.85 ± 0.14i | 12.76 ± 0.03f | 8.96 ± 0.66e | 28.57h |

| ‘Wojtek’ | 2.94 ± 0.08r | 9.32 ± 0.13i | 0.40 ± 0.06m | 12.65m |

Total F, total amount of quantified flavan-3-ols; 1 Values are expressed as the mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c, etc.) within the same column are statistically different (p < 0.05). 2 ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’, ‘Bakcharskaya Yubileynaya’; ‘Leningradskii V.’, ‘Leningradskii Velikan’.

Table 6.

Phenolic acid content (mg/100 g fw) of different blue honeysuckle cultivars and genotypes.

| Cultivar/Genotype | 3-CQA | 5-CQA | CQA | di CQA 1 | di CQA 2 | di CQA 3 | Total PA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Amphora’ | 0.35 ± 0.00n 1 | 36.43 ± 0.91i | 4.42 ± 0.35ij | 5.44 ± 0.22no | 1.04 ± 0.07efgh | 0.34 ± 0.04jkl | 48.01jk |

| ‘Amur’ | 3.50 ± 0.13h | 46.31 ± 1.35e | 5.45 ± 0.18f | 5.81 ± 0.31no | 1.01 ± 0.01efgh | 0.33 ± 0.02jklm | 62.40ghi |

| ‘Atut’ | 0.57 ± 0.04mn | 25.22 ± 0.97l | 4.11 ± 0.03k | 11.86 ± 0.56ijkl | 1.17 ± 0.06defg | 0.95 ± 0.01ef | 43.88kl |

| ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’ 2 | 3.66 ± 0.05h | 50.74 ± 0.10d | 4.02 ± 0.01k | 33.93 ± 3.23b | 1.86 ± 0.16c | 1.40 ± 0.16d | 95.62b |

| ‘Berry Smart Blue’ | 3.53 ± 0.05h | 33.88 ± 0.05j | 5.13 ± 0.22fg | 5.92 ± 0.11no | 0.66 ± 0.02fhi | 0.50 ± 0.01ij | 49.61j |

| ‘Blue Velvet’ | 0.55 ± 0.05mn | 23.14 ± 0.16mn | 0.25 ± 0.00n | 20.40 ± 4.44ef | 0.06 ± 0.02j | 0.10 ± 0.07n | 44.50kl |

| ‘Chelyabinka’ | 6.17 ± 0.27d | 57.87 ± 1.34b | 8.97 ± 0.08a | 13.48 ± 0.28hij | 1.60 ± 0.11cd | 1.01 ± 0.06e | 89.10cd |

| ‘Chernichka’ | 4.84 ± 0.07f | 39.28 ± 0.71h | 4.13 ± 0.11jk | 26.30 ± 0.16cd | 2.62 ± 0.40b | 1.43 ± 0.07d | 78.60e |

| ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’ | 9.95 ± 0.26c | 49.66 ± 1.73d | 7.30 ± 0.07c | 25.62 ± 1.21cd | 2.45 ± 0.43b | 2.03 ± 0.39b | 97.01b |

| ‘Fialka’ | 0.86 ± 0.02m | 58.47 ± 1.17b | 8.23 ± 0.32b | 9.73 ± 1.28klm | 1.17 ± 0.33defg | 0.59 ± 0.00ghi | 79.05e |

| ‘Goluboe Vereteno’ | 4.34 ± 0.20g | 43.55 ± 2.26f | 5.03 ± 0.15gh | 10.68 ± 2.10ijkl | 1.10 ± 0.01efgh | 0.52 ± 0.02hij | 65.22gh |

| ‘Jolanta’ | 4.69 ± 0.16f | 22.76 ± 0.14mn | 3.22 ± 0.12l | 11.25 ± 0.68ijkl | 1.28 ± 0.10defg | 0.76 ± 0.02fg | 43.96kl |

| ‘Kamchadalka’ | 5.45 ± 0.13e | 60.37 ± 0.70a | 5.97 ± 0.04e | 17.31 ± 3.64fg | 1.04 ± 0.47efgh | 0.83 ± 0.16ef | 90.96c |

| ‘Karina’ | 4.24 ± 0.02g | 25.09 ± 0.10l | 3.44 ± 0.09l | 12.55 ± 1.20ijk | 1.46 ± 0.23cde | 0.82 ± 0.07ef | 47.60jk |

| ‘Klon 38’ | 4.90 ± 0.11f | 24.05 ± 0.43lm | 3.45 ± 0.04l | 9.71 ± 0.96klm | 0.79 ± 0.09fgh | 0.74 ± 0.03fg | 43.64kl |

| ‘Klon 40’ | 5.78 ± 0.12e | 37.07 ± 0.46i | 0.43 ± 0.01n | 6.00 ± 0.54no | 0.65 ± 0.07hi | 0.12 ± 0.01mn | 50.06j |

| ‘Klon 44’ | 0.39 ± 0.04mn | 17.24 ± 1.11o | 2.30 ± 0.01m | 6.00 ± 0.19no | 0.78 ± 0.04fgh | 0.39 ± 0.03ijkl | 27.11n |

| ‘Krupnoplodnaya’ | 2.60 ± 0.02j | 41.56 ± 0.04g | 0.31 ± 0.02n | 14.08 ± 0.49ghi | 0.05 ± 0.01j | 0.08 ± 0.02n | 58.68i |

| ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’ | 3.65 ± 0.02h | 31.35 ± 0.23k | 0.16 ± 0.00n | 4.92 ± 0.28no | 1.02 ± 0.03efgh | 0.20 ± 0.01lmn | 41.30l |

| ‘Leningradskii V.’ | 1.52 ± 0.12l | 46.78 ± 0.24e | 0.46 ± 0.02m | 11.91 ± 0.70ijkl | 0.25 ± 0.02ij | 0.04 ± 0.00n | 60.95hi |

| ‘Morena‘ | 5.56 ± 0.20e | 46.82 ± 1.69e | 5.93 ± 0.55e | 5.55 ± 0.20no | 1.37 ± 0.03de | 0.34 ± 0.01jkl | 65.57g |

| ‘Nympha’ | 4.22 ± 0.25g | 47.70 ± 1.18e | 4.65 ± 0.35hi | 4.07 ± 0.09o | 1.38 ± 0.03cde | 0.22 ± 0.01klmn | 62.24ghi |

| ‘Roksana’ | 2.19 ± 0.12k | 34.27 ± 0.65j | 3.45 ± 0.32k | 27.33 ± 0.33c | 2.37 ± 0.51b | 1.45 ± 0.13d | 71.06f |

| ‘Sineglazka’ | 5.72 ± 0.43e | 51.64 ± 1.03cd | 7.42 ± 0.12c | 10.37 ± 0.68jklm | 0.83 ± 0.03fgh | 0.80 ± 0.07efg | 76.78e |

| ‘Tomichka’ | 10.48 ± 0.07b | 52.77 ± 0.66c | 8.41 ± 0.13b | 37.39 ± 0.86a | 3.21 ± 0.44a | 3.23 ± 0.00a | 115.50a |

| ‘Vasilevskaya’ | 0.57 ± 0.01mn | 51.54 ± 0.19cd | 6.84 ± 0.23d | 23.08 ± 1.11de | 1.63 ± 0.10cd | 1.66 ± 0.10c | 85.32d |

| ‘Viola’ | 12.57 ± 0.13a | 25.63 ± 0.34l | 2.40 ± 0.03l | 16.21 ± 3.72gh | 1.44 ± 0.05cde | 0.72 ± 0.17fgh | 58.99i |

| ‘Volshebnica’ | 4.79 ± 0.26f | 51.31 ± 0.08cd | 5.72 ± 0.05e | 14.27 ± 0.35ghi | 0.99 ± 0.15efgh | 0.95 ± 0.01ef | 78.03e |

| ‘Vostorg’ | 4.35 ± 0.08 | 35.31 ± 0.02g | 8.40 ± 0.77lmn | 48.07jk | |||

| ‘Wojtek’ | 3.18 ± 0.03i | 21.75 ± 0.03n | 2.40 ± 0.04m | 7.08 ± 0.45mno | 0.79 ± 0.05fgh | 0.44 ± 0.02ijk | 35.63m |

3-CQA, neochlorogenic acid; 5-CQA, chlorogenic acid; CQA, caffeoylquinic acid; di CQA 1, dicaffeoylquinic acid isomer 1; di CQA 2, dicaffeoylquinic acid isomer 2; di CQA 3, dicaffeoylquinic acid isomer 3; Total PA, total amount of quantified phenolic acids; 1 Values are expressed as the mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c, etc.) within the same column are statistically different (p < 0.05). 2 ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’, ‘Bakcharskaya Yubileynaya’; ‘Leningradskii V.’, ‘Leningradskii Velikan’.

Table 7.

Antioxidant activity (μmol TE/g fw) of different blue honeysuckle cultivars and genotypes.

| Cultivar/Genotype | DPPH | FRAP |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Amphora’ | 16.57 ± 1.89f 1 | 44.57 ± 1.30ef |

| ‘Amur’ | 26.66 ± 1.77b | 55.69 ± 1.47b |

| ‘Atut’ | 8.80 ± 0.17n | 22.86 ± 1.15s |

| ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’ 2 | 13.53 ± 0.18i | 33.51 ± 1.14lm |

| ‘Berry Smart Blue’ | 11.70 ± 0.14klm | 31.61 ± 0.92n |

| ‘Blue Velvet’ | 18.50 ± 1.61e | 28.23 ± 0.51op |

| ‘Chelyabinka’ | 14.95 ± 0.44g | 41.03 ± 1.86i |

| ‘Chernichka’ | 11.43 ± 0.29lm | 28.74 ± 1.64op |

| ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’ | 15.80 ± 0.18fg | 43.10 ± 1.37fg |

| ‘Fialka’ | 16.40 ± 0.34f | 42.72 ± 1.40gh |

| ‘Goluboe Vereteno’ | 12.92 ± 0.49ij | 35.07 ± 1.25kl |

| ‘Jolanta’ | 27.30 ± 0.94b | 52.77 ± 1.72c |

| ‘Kamchadalka’ | 11.83 ± 0.84jklm | 31.10 ± 0.90n |

| ‘Karina’ | 8.94 ± 0.27n | 22.41 ± 0.67s |

| ‘Klon 38’ | 11,06 ± 0.32m | 29,07 ± 1.24o |

| ‘Klon 40’ | 28.77 ± 1.43a | 57.52 ± 0.78a |

| ‘Klon 44’ | 9.80 ± 0.67n | 25.04 ± 1.10r |

| ‘Krupnoplodnaya’ | 18.89 ± 0.82e | 27.28 ± 1.33p |

| ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’ | 26.48 ± 0.89b | 50.41 ± 2.34d |

| ‘Leningradskii V.’ | 18.90 ± 0.72e | 31.52 ± 1.57n |

| ‘Morena‘ | 15.59 ± 0.96fg | 45.80 ± 0.92e |

| ‘Nympha’ | 23.89 ± 0.31c | 50.24 ± 1.54d |

| ‘Roksana’ | 11.63b ± 0.19klm | 32.06 ± 1.09mn |

| ‘Sineglazka’ | 14.77 ± 0.33gh | 41.32 ± 0.77hi |

| ‘Tomichka’ | 13.74 ± 0.75hi | 37.94 ± 1.32j |

| ‘Vasilevskaya’ | 12.78 ± 0.86ijk | 32.58 ± 1.47mn |

| ‘Viola’ | 11.46 ± 0.84lm | 28.14 ± 1.08op |

| ‘Volshebnica’ | 12.29 ± 0.29jkl | 31.35 ± 1.07n |

| ‘Vostorg’ | 22.69 ± 1.62d | 42.74 ± 1.78ghi |

| ‘Wojtek’ | 19.54 ± 1.95e | 35.52 ± 2.79k |

1 Values are expressed as the mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation. Mean values with different letters (a, b, c, etc.) within the same column are statistically different (p < 0.05). 2 ‘Bakcharskaya Y.’, ‘Bakcharskaya Yubileynaya’; ‘Leningradskii V.’, ‘Leningradskii Velikan’.

The qualitative and quantitative compositions of iridoids were very different for all cultivars and genotypes. Five of the 14 identified iridoids, i.e., 8-epi-LA, pLo, pentosyl-sweroside (pS), 7-epi-loganin (7-epi-Lo), and secoxyloganin (secoxyLo), were present in trace amounts in the studied berries. The content of a further nine iridoids in fresh honeysuckle berries is presented in Table 2. Four of them (LA, 7-epi-loganic acid 7-O-pentoside (7-epi-LAp), loganin (Lo), and sweroside (S)) were present in all cultivars and genotypes, but there were differences in their levels: LA > Lo + S > 7-epi-LAp. Five other iridoids (7-epi-LA, loganic acid 7-O-pentoside (LAp), loganin 7-O-pentoside (Lop), 7-epi-loganin 7-O-pentoside (7-epi-Lop), and secologanin (secoLo)) were present in some cultivars only. The total quantified iridoid content in honeysuckle berries covered a wide range from 119.95 mg/100 g fresh weight (fw) (‘Dlinnoplodnaya’) to 276.43 mg/100 g fw (‘Berry Smart Blue’). The average total content of quantified iridoids, evaluated by HPLC analysis, was 180.77 mg/100 g fw. We previously observed higher, in terms of the average value, total content of quantified iridoids in cornelian cherry fruits and honeysuckle berry [18,26]. Contents of LA and its derivatives were more than twice the content of Lo, S, and their derivatives. In honeysuckle berries, the dominant compound among iridoids was LA (mean 81.09 mg/100 g fw). The lowest amount of this compound (35.22–39.21 mg/100 g fw) was found in ‘Vostorg’, ‘Sineglazka’, and ‘Chelyabinka’, whereas the highest (182.28 mg/100 g fw) was found in ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’. LA represented between 22% and 73% of the total content of quantified iridoids in honeysuckle berry. This range is very wide and depends strongly on the cultivar or genotype. In our previous studies, we investigated LA content in many cornelian cherry cultivars, but the percentage content of iridoid in these fruits was in a narrower range, i.e., 88%–96% [26]. The high LA content is beneficial, because this compound exhibits biological activity. Many authors have shown that LA has strong anti-inflammatory properties [33,34,35]. In studies in rabbits Sozański et al. [34,35] revealed that LA diminished diet-induced dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis, increased PPAR-α and PPAR-γ expression, and exhibited anti-inflammatory activity. In the ten cultivars of analyzed berries, there was determined the epi-isomer of LA, which constituted 11% of the total amount of quantified iridoids, on average. The highest amount of this compound (45.05 mg/100 g fw) was present in ‘Viola’. epi-LA, like LA, also exhibits biological activity. According to Dinda et al. [36], epi-LA exhibited strong antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

LAp and 7-epi-LAp were the two major derivatives of isomers of LA, but the first compound was about three times more abundant than the second. Concentrations of LAp ranged from 9.37 mg/100 g fw in “Blue Velvet” to 71.16 mg/100 g fw in ‘Kamchadalka’. This compound was identified in 24 cultivars, excluding ‘Bakcharskaya’, ‘Karina’, ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’, ‘Goluboe Vereteno’, and ‘Wojtek’. The average content of LAp was 31.72 mg/100 g fw. 7-epi-LAp appeared in all cultivars, and the average amount was 11.70 mg/100 g fw. ‘Bakcharskaya’, Atut’, and ‘Viola’ contained the lowest amount of this compound (2.86–3.69 mg/100 g fw), while ‘Morena’ contained the highest amount (20.43 mg/100 g fw). To our knowledge, there are no reports on the occurrence of pentose derivatives of loganic acid in other raw materials.

For all cultivars, the total content of Lo and S ranged from 1.87 mg/100 g fw (‘Tomichka’) to 71.71 mg/100 g fw (‘Wojtek’). The average content of these iridoids found in the berries was 19.00 mg/100 g fw, which accounted for 10% of all iridoids. These iridoids are not the main components of berries, but their presence in the fruit is important for their health benefits, such as antispasmodic and antibacterial activities [36,37]. The results of Ma et al. [38] showed that Lo and its derivatives were active against diabetic nephropathy. In addition, higher concentrations of L and S may increase the bitter taste of berries. Other fruits reported to contain both Lo and S are Cornus officinalis and Cornus mas [39,40,41]. According to Du et al. [39] and Zhou et al. [40], Lo, beside morroniside, is one of the main iridoids in the fruits of C. officinalis, while S is the minor iridoid in this fruit. Both compounds are present in trace amounts in C. mas fruits [41].

Among pentose derivatives of Lo, the most important compounds are Lop and 7-epi-Lop. Lop, similarly to LAp, was present in the same 24 cultivars. It was not detected in ‘Bakcharskaya’, ‘Karina’, ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’, ‘Goluboe Vereteno’, or ‘Wojtek’. Concentrations of Lp ranged from 5.85 mg/100 g fw in ‘Viola’ to 83.85 mg/100 g fw in ‘Amphora’. The average content of this compound was 35.79 mg/100 g fw, which accounted for 20% of all iridoids. 7-epi-Lop was found in only 14 cultivars. The lowest amount of this iridoid (1.83 mg/100 g fw) was found in ‘Chernichka’, whereas the highest (9.11 mg/100 g fw) was found in the ‘Blue Velvet’ cultivar. Similarly as in the case of the derivatives of LAp, there are no reports on the prevalence of the derivatives of Lop in other raw materials.

The 24 cultivars of berries contained secoLo. Among cultivars, the concentration of this compound ranged from 0.88 mg/100 g fw in ‘Leningradskii Velikan’ to 13.30 mg/100 g fw in ‘Klon 44’. secoLo occurs in Lonicera [42,43] and Cornus [44] species. According to Graikou et al. [37], secoLo, similarly to Lo, has antimicrobial activity but only against Gram-positive bacteria.

Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 show the contents of individual phenolic compounds of 30 honeysuckle berry cultivars and genotypes. The major polyphenolic groups detected in honeysuckle berries in this study were similar to those reported in previous studies [3]. They were anthocyanins, flavonols, flavones, flavan-3-ols, and phenolic acids. Additionally, in this work, we identified compounds from another polyphenolic group, i.e., flavanonols.

Blue honeysuckle, like chokeberry and bilberry, is a rich source of anthocyanins [4,6,45]. The studied 30 cultivars of berries contain from 151.74 mg/100 g fw (‘Viola’) to 655.21 mg/100 g fw ('Amur') of these pigments (Table 3). Among the anthocyanins in honeysuckle berries, there were 5 compounds. Cy 3-glc was the major anthocyanin (83%–93%). High amounts of this anthocyanin were found in ‘Amur’ and ‘Klon 40’ (577.19 and 560.76 mg/100g), whereas low amounts were found in ‘Karina’ and ‘Viola’ (135.41 and 136.37 mg/100 g). The other four anthocyanins were present in smaller amounts: Cy 3-rut (1%–9%), Cy 3,5-diglc (2%–6%), Pn 3-glc (1%–5%), and Pn 3-glc and Pn 3-rut (>2%). Other authors, in addition to the above-mentioned six anthocyanins, have identified other compounds from this group, but their content is small [6,46].

Concentration of the three main flavonols (quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside-hexoside (Q-rha-hex), quercetin 3-O-vicianoside (Q-vic), and quercetin 3-O-glucoside (Q 3-glc)) in 30 honeysuckle berry cultivars and genotypes ranged from 10.65 mg/100 g fw (‘Roksana’) to 35.46 mg/100 g fw (‘Klon 40’) (Table 4). The dominant flavonol was Q-rha-hex. High amounts of this compound were found in ‘Amur’ and ‘Nympha’ (24.10 mg/100 g fw and 24.21 mg/100 g fw), whereas low amounts were observed in ‘Roksana’ (1.50 mg/100 g fw). The average content of Q-rha-hex, Q-vic, and Q 3-glc was 12.18 mg/100 g fw, 5.30 mg/100 g fw, and 4.13 mg/100 g fw, respectively. We previously identified the second of these compounds in chokeberry juices [47]. From the two identified flavanonols, only taxifolin 7-hexoside (Tx 7-hex) was quantitated (Table 4). The content of the compound ranged from 2.80 mg/100 g fw in ‘Viola’ to 14.56 mg/100 g fw in ‘Nympha’. A high concentration of this compound, above 10 mg/100 g fw, has also been observed in 5 cultivars of berries (‘Amur’, ‘Jolant’, ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’, ‘Morena’, and ‘Klon 40’). A lower content of derivatives of taxifolin was determined in fruits of R. canina and R. micrantha [31].

The concentration of flavones in the 30 cultivars and genotypes of honeysuckle berries was low. Among these compounds, only luteolin-trihexoside (L-trihex) was quantitatively determined; its content ranged from 0.09 mg/100 g (‘Klon 44’) to 1.07 mg/100 g fw (‘Morena’) (Table 4). It was not detected in ‘Bakcharskaya’ or ‘Roksana’. A similar level of L-trihex was observed in a previous study in ‘Wojtek’ cultivar [3]. According to Jurikova et al. [7], the content of luteolin 7-O-glucoside ranged from 4.70 mg to 13.60 mg in 100 g of berries of different Lonicera species. Flavones are rarely found in fruits. More often, they are present in vegetables, in particular in the leaves of celery [48].

The contents of (+)-catechin (Cat) and two procyanidin (PC) dimers in honeysuckle berries are shown in Table 5. Between tested cultivars, low levels of Cat and dimer 1 (tR 2.66 min) were found in ‘Blue Velvet’, whereas ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’ contained high amounts. The content of dimer 2 (tR 4.05 min) ranged from 0.40 mg/100 g fw (‘Wojtek’) to 20.92–21.77 mg/100 g fw (‘Viola’, ‘Chelyabinka’, ‘Vasilevskaya’, and ‘Roksana’).

The total content of quantified phenolic acids ranged from 27.11 mg/100 g fw in ‘Klon 44’ to 115.50 mg/100 g fw in ‘Tomichka’ (Table 6), and it was comparable to the quantities obtained by other authors [3,4]. High concentrations of these compounds have also been observed in 9 cultivars of berries (‘Bakcharskaya’, ‘Chelyabinka’, ‘Chernichka’, ‘Dlinnoplodnaya’, ‘Fialka’, ‘Kamchadalka’, ‘Sineglazka’, ‘Vasilevskaya’, and ‘Volshebnica’), with a value in the range 76.78–97.01 mg/100 g fw. 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid (5-CQA, chlorogenic acid) was the most predominant phenolic acid found in berries and constituted on average more than 60% of the total amount of quantified hydroxycinnamic acids (HCA). The lowest amount of this compound (17.24 mg/100 g fw) was found in ‘Klon 44’, whereas the highest (60.37 mg/100 g fw) was found in the ‘Kamchadalka’ cultivar. The second acid present in large quantities (from 4.07 in ‘Nympha’ to 37.39 mg/100 g fw in ‘Tomichka’) was dicaffeoylquinic acid 1 (di-CQA 1). It constituted from 7% to 46% of the total amount of quantified phenolic acids. Similar results for these two acids have been reported by other authors [14,45]. The 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid (3-CQA) and caffeoylquinic acid (CQA) concentrations ranged from 0.35 mg/100 g fw (‘Amphora’) to 12.57 mg/100 g fw (‘Viola’), and from 0.16 mg/100 g fw (‘Kuwszinowidnaja’) to 8.97 mg/100 g fw (‘Chelyabinka’), respectively. The other two di-CQA isomers were present in smaller amounts: di-CQA 2 (0.05–3.21 mg/100 g fw) and di-CQA 3 (0.04–3.23 mg/100 g fw). Oszmiański et al. [3] for ‘Wojtek’ cv. reported the contents of di-CQA 2 and di-CQA 3 at the level of 0.15 mg/100 g fw, and this value was lower than the value for ‘Wojtek’ cv in this study. Other authors, among phenolic acids, identified only 3-CQA and 5-CQA, without the isomer di-CQA [14,45].

2.3. Antioxidant Activities of Cultivars and Ecotypes of Honeysuckle Berries

The antioxidant activity (1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH) and ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP)) of the blue honeysuckle berries of 30 cultivars and genotypes is shown in Table 7. The effects of compounds present in the berries on the antioxidant activity measured by the DPPH assay ranged from 8.80 to 28.77 μmol TE/g fw, and for the FRAP assay they ranged from 22.41 to 57.52 μmol TE/g fw. ‘Amur’, ‘Jolanta’, ‘Klon 40’, ‘Kuvshinovidnaya’, and ‘Nympha’ were characterized by high activity measured by both DPPH (26.48–28.77 μmol TE/g fw) and FRAP (50.24–57.52 μmol TE/g fw). Low activity was observed for ‘Atut’ (8.80 μmol TE/g fw for DPPH and 22.86 μmol TE/g fw for FRAP) and ‘Karina’ (8.94 μmol TE/g fw for DPPH and 22.41 μmol TE/g fw for FRAP). These results showed that DPPH and FRAP assays for 30 cultivars and genotypes revealed the same trend. Similar results for ABTS and FRAP assays have been reported previously by other authors [11]. High activity of honeysuckle berries has been confirmed by many authors [2,8,10,13], although the level of activity depends on many factors including cultivar. The differences in antioxidant activity between honeysuckle berry cultivars and genotypes may result from different qualitative and quantitative constituents.

The correlation between the antioxidant activity of honeysuckle berry extracts and the content of anthocyanins depends on the measurement method (Table S2). Correlation coefficients were higher for the FRAP method (r = 0.94) than the DPPH method (r = 0.78). A very strong correlation was observed between the antioxidant potential (FRAP) and anthocyanins (r = 0.94), and there was a strong correlation between the antioxidant potential (DPPH) and anthocyanins (r = 0.78).

These are the first studies on the correlation of the antioxidant activity of honeysuckle extract with the amount of iridoids. The obtained results showed that the amount of iridoids weakly correlated with in vitro antioxidant activity measured by DPPH and FRAP methods. This is due to the structure of iridoids, which in their molecule do not have (or they have, but only few) phenolic OH groups, which neutralize free radicals. This is consistent with the study of Pacifico et al. [49]. The authors reported that iridoids did not exhibit a good radical scavenging capacity. They explained that the moderate radical scavenging capacity is probably due to their poor hydrogen-donating ability. Iridoids exhibit higher biological activity, especially anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activity [33,34,35]; therefore their high content in blue honeysuckle berries can complement the antioxidant effect of phenolic compounds. Thus, honeysuckle berries may have wider potential than other fruits containing only polyphenols.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagent and Standard

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH); 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox); 2,4,6-tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), FeCl3, acetonitrile, formic acid, sweroside (S), and secologanin (SLo) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). Acetic acid was obtained from Chempur (Piekary Śląskie, Poland). Acetonitrile for LC–MS was purchased from POCh (Gliwice, Poland). Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside (Cy 3-glc) and p-coumaric acid (p-CuA), caffeic acid (CA), ferulic acid (FA), quercetin 3-O-glucoside, luteolin 7-O-glucoside (Lglc), luteolin 7-O-rutinoside, diosmin, hesperidin, naringin, rutin, (+)-catechin, (−)-epicatechin, procyanidin B1, loganic acid (LA), and loganin (Lo) were purchased from Extrasynthese (Lyon Nord, France). 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid (5-CQA, chlorogenic acid), 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid (3-CQA, neochlorogenic acid), and 4-O-caffeoylquinic acid (4-CQA, cryptochlorogenic acid) were purchased from TRANS MIT GmbH (Giessen, Germany). All reagents were of analytical grade.

3.2. Plant Materials

Honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea L. var. kamtschatica Sevast.) from 6 cultivars (‘Amphora’, ‘Amur’, ‘Berry Smart Blue’, ‘Fialka’, ‘Morena’, ‘Nympha’) were harvested in the Arboretum and Institute of Physiography in Bolestraszyce (59°51′ N, 22°51′ E)), near Przemyśl, Poland, 14 cultivars (‘Atut’, ‘Bakczarskaja’, ‘Czelabinka’, ‘Czerniczka’, ‘Dilnnopłodnaja’, ‘Kamczadałka’, ‘Karina’, ‘Niebieskie Czeretenko’, ‘Roksana’, ‘Sinigłaska’, ‘Tomiczka’, ‘Viola’, ‘Wasilewkaja’, ‘Wołoszebnica’) and 2 genotypes (Klon 38 and 44) were harvested in the Research Station for Cultivar Testing in Masłowice (51°15′ N, 18°38′ E), Poland, 6 cultivars (‘Blue Velvet’, ‘Jolanta’, ‘Krupnopłodnaja’, ‘Kuwszinowidnaja’, ‘Leningradzkij Wielikan’, ‘Wojtek’) and 1 genotype (Klon 40) were harvested in the Polish Academy of Sciences Botanical Garden, Centre for Biological Diversity Conservation in Powsin (52°07′ N, 21°06′ E), and 1 cultivar (‘Vostorg’) was harvested in a horticultural farm in Dąbie near Silnowo (53°66′ N, 16°45′ E).

The plant materials were authenticated by Professor Jakub Dolatowski (Arboretum and Institute of Physiography in Bolestraszyce, Poland) and Aleksandra Siwik M.Sc. (the Research Station for Cultivar Testing in Masłowice).

3.3. Extraction of Compounds for Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

Frozen berries of honeysuckle were homogenized and 5 g of the homogenate was extracted with 50 mL of 80% aqueous methanol (v/v) acidified with 1% HCl by ultrasonication for 20 min. The extract was centrifuged and diluted (re-distilled water with the ratio 1:1, v/v). For UPLC-qTOF-MS/MS and HPLC-PDA analysis the supernatant was filtered through a Hydrophilic PTFE 0.22 and 0.45 μm membrane (Millex Samplicity Filter, Merck, Germany) and used for routine investigation.

3.4. Identification of Iridoids and Polyphenols by UPLC-qTOF-MS/MS

The method was previously described by Wyspiańska et al. [50]. Identification of compounds was performed using the Acquity ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system, coupled with a quadrupole-time of flight (Q-TOF) MS instrument (UPLC/Synapt Q-TOF MS, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA), with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Separation was achieved on an Acquity BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 μm; Waters). The mobile phase was a mixture of 2.0% aq. formic acid v/v (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient program was as follows: initial conditions—1% B in A, 12 min—25% B in A, 12.5 min—100% B, 13.5 min—1% B in A. The flow rate was 0.45 mL/min and the injection volume was 5 μL. The column was operated at 30 °C. UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on-line during UPLC analysis, and the spectral measurements were made in the wavelength range of 200–600 nm, in steps of 2 nm. The major operating parameters for the Q-TOF MS were set as follows: capillary voltage 2.0 kV, cone voltage 40 V, cone gas flow of 11 L/h, collision energy 28–30 eV, source temperature 100 °C, desolvation temperature 250 °C, collision gas, argon; desolvation gas (nitrogen) flow rate, 600 L/h; data acquisition range, m/z 100–2000 Da; ionization mode, negative and positive. The data were collected with Mass-LynxTM V 4.1 software (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). The runs were monitored at the following wavelengths: iridoids at 245 nm, phenolic acids and their derivatives at 320 nm, flavan-3-ols, flavonols, flavanonols, flavones and flavanones at 280 and 360 nm, anthocyanins at 520 nm.

3.5. Quantification of Iridoids and Polyphenols by HPLC-PDA

The analysis was previously described by Sokół-Łętowska et al. [51]. The HPLC-PDA analysis was performed using a Dionex (Germering, Germany) system equipped with the diode array detector model Ultimate 3000, quaternary pump LPG-3400A, autosampler EWPS-3000SI, thermostated column compartment TCC-3000SD, and controlled by Chromeleon v.6.8 software (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The Cadenza Imtakt column C5-C18 (75 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) was used. The mobile phase was composed of solvent C (4.5% aq. formic acid, v/v) and solvent D (100% acetonitrile). The elution system was as follows: 0–1 min 5% D in C, 20 min 25% D in C, 21 min 100% D, 26 min 100% D, 27 min 5% D in C. The flow rate of the mobile phase was 1.0 mL/min and the injection volume was 20 μL. The column was operated at 30 °C. Iridoids were detected at 245 nm, flavan-3-ols at 280 nm, phenolic acids and their derivatives at 320 nm, flavonols, flavanonols, flavones and flavanones at 280 and 360 nm, and anthocyanins at 520 nm.

Loganic acid and its derivatives were expressed as mg of loganic acid equivalents (LAE) per 100 g fresh weight (fw), loganin, sweroside and their derivatives as loganin equivalents (LoE) per 100 g fw, anthocyanins as cyanidin 3-O-glucoside equivalents (CygE) per 100 g fw, derivatives of quercetin and taxifolin as quercetin 3-O-glucoside equivalents (QgE) per 100 g fw, luteolin -O-dihexoside-hexoside as luteolin 7-O-glucoside equivalents (LgE) per 100 g fw, caffeoylquinic acids as mg of 5-O-caffeoylquinic (chlorogenic) acid equivalents (ChAE) per 100 g fw. Solutions of standards (1 mg/ml) were dissolved in 1 mL of methanol. The appropriate amounts of stock solutions were diluted with 50% aqueous methanol (v/v) acidified with 1% HCl in order to obtain standard solutions. Analytical characteristics for determination of phenolic compounds and iridoids are shown in Table S3.

3.6. Antioxidant Capacity

The total antioxidant potential of samples was determined using a ferric reducing antioxidant power ability of plasma (FRAP) assay by Benzie and Strain [52] as a measure of antioxidant power. The FRAP reagent was prepared by mixing acetate buffer (300 μM, pH 3.6), a solution of 10 μM TPTZ in 40 μM HCl, and 20 μM FeCl3 at 10:1:1 (v/v/v). The DPPH radical scavenging activity of samples was determined according to the method of Yen and Chen [53]. DPPH (100 μM) was dissolved in pure ethanol (96%). All determinations were performed in triplicate using a UV-2401 PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The absorbance was measured after 10 min at 593 nm for FRAP and at 517 nm for DPPH. For all analyses, a standard curve was prepared using different concentrations of Trolox. Calibration curves, in the range 0.01–5.00 μmol Trolox L−1, were used for the quantification of the three methods of antioxidant activity, showing good linearity (r2 ≥ 0.998). The results were corrected for dilution and expressed in μmol Trolox equivalent (TE) per 100 g fw.

3.7. Statistical Analyses

Results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three technical replications. All statistical analyses were performed with Statistica version 12.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by Duncan’s test was used to compare the mean values. Differences were considered to be significant at α = 0.05.

4. Conclusions

The reported research clearly shows that honeysuckle berries are an excellent source not only of polyphenols (mainly anthocyanins), but also of iridoids, which are rarely present in other fruits. The content of both iridoids and polyphenols and antioxidant activity measured by DPPH and FRAP methods depends largely on the cultivar of berries. All 27 cultivars and 3 genotypes of blue honeysuckle berries had similar anthocyanin, flavonol, flavanonol, flavone, flavan-3-ol, and phenolic acid profiles, but did not have similar iridoid profiles. Two iridoids, two flavanones, and three flavones were identified in honeysuckle berries for the first time. The content of iridoids, besides anthocyanins, may be one of the most important parameters for appraising the characterization of blue honeysuckle fruits with respect to their nutraceutical value and potential use for different purposes.

Acknowledgments

Publication supported by Wroclaw Centre of Biotechnology, Leading National Research Centre program (KNOW) for years 2014–2018. We are grateful to Stanisław Dolata and Jacek Olejniczak (horticultural farm in Dąbie near Silnowo, Poland) and Ryszard Rawski (Warsaw University Botanic Garden, Poland), Aleksandra Siwik (Research Station for Cultivar Testing in Masłowice) for sharing fruits of several cultivars of honeysuckle berries.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials are available online.

Author Contributions

A.Z.K., A.S.-Ł. and I.F. conceived, designed, and performed the experiments and wrote the paper. A.Z.K., I.F., A.S.-Ł., J.O., and N.P. analyzed and interpreted the experimental results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the analyzed frozen fruits are available from the authors.

References

- 1.Oszmiański J., Kucharska A., Gasiewicz E. Usefulness of honeysuckle fruits for juice production. In: Michalczuk L., Płocharski W., editors. Fruit and Vegetable Juices and Drinks Today and in the XXI Century. Research Institute of Pomology and Floriculture; Rytro, Poland: 1999. pp. 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson M., Chaovanalikit A. Preliminary observations on adaptation and nutraceutical values of blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea) in Oregon. Acta Hortic. 2003;626:65–72. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2003.626.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oszmiański J., Wojdyło A., Lachowicz S. Effect of dried powder preparation process on polyphenolic content and antioxidant activity of blue honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea L. var. kamtschatica) LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016;67:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.11.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaovanalikit A., Thompson M.M., Wrolstad R.E. Characterization and quantification of anthocyanins and polyphenolics in blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:848–852. doi: 10.1021/jf030509o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin X.H., Ohgami K., Shiratori K., Suzuki Y., Koyama Y., Yoshida K., Ilieva I., Tanaka T., Onoe K., Ohno S. Effects of blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) extract on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Eye Res. 2006;82:860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palikova I., Heinrich J., Bednar P., Marhol P., Kren V., Cvak L., Valentová K., Ruzicka F., Holá V., Kolár M., et al. Constituents and antimicrobial properties of blue honeysuckle: A novel source for phenolic antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:11883–11889. doi: 10.1021/jf8026233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurikova T., Rop O., Mlcek J., Sochor J., Balla S., Szekeres L., Hegedusova A., Hubalek J., Adam V., Kizek R. Phenolic profile of edible honeysuckle berries (genus Lonicera) and their biological effects. Molecules. 2012;17:61–79. doi: 10.3390/molecules17010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rupasinghe H.P.V., Yu L.J., Bhullar K.S., Bors B. Haskap (Lonicera caerulea): A new berry crop with high antioxidant capacity. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2012;92:1311–1317. doi: 10.4141/cjps2012-073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rop O., Reznicek V., Mlcek J., Jurikova T., Balik J., Sochor J., Kramarova D. Antioxidant and radical oxygen species scavenging activities of 12 cultivars of blue honeysuckle fruits. Hortic. Sci. 2011;38:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusznierewicz B., Piekarska A., Mrugalska B., Konieczka P., Namieśnik J., Bartoszek A. Phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of Polish blue-berried honeysuckle genotypes by HPLCDAD-MS, HPLC postcolumn derivatization with ABTS or FC, and TLC with DPPH visualization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:1755–1763. doi: 10.1021/jf2039839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojdyło A., Jáuregui P.N.N., Carbonell-Barrachina A.A., Oszmiański J., Golis T. Variability of phytochemical properties and content of bioactive compounds in Lonicera caerulea L. var. kamtschatica berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:12072–12084. doi: 10.1021/jf404109t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jurikova T., Sochor J., Rop O., Mlcek J., Balla S., Szekeres L., Zitny R., Zitka O., Adam V., Kizek R. Evaluation of polyphenolic profile and nutritional value of non-traditional fruit species in the Czech Republic—A comparative study. Molecules. 2012;17:8968–8981. doi: 10.3390/molecules17088968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sochor J., Jurikova T., Pohanka M., Skutkova H., Baron M., Tomaskova L., Balla S., Klejdus B., Pokluda R., Mlcek J., et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activity, polyphenolic compounds, amino acids and mineral elements of representative genotypes of Lonicera edulis. Molecules. 2014;19:6504–6523. doi: 10.3390/molecules19056504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khattab R., Brooks M.S.-L., Ghanem A. Phenolic analyses of haskap berries (Lonicera caerulea L.): Spectrophotometry versus high performance liquid chromatography. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016;19:1708–1725. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2015.1084316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gervasi T., Oliveri F., Gottuso V., Squadrito M., Bartolomeo G., Cicero N., Dugo G. Nero d’Avola and Perricone cultivars: Determination of polyphenols, flavonoids and anthocyanins in grapes and wines. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016;30:2329–2337. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1174229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anikina E.V., Syrchina A.I., Vereshchagin A.L., Larin M.F., Semenov A.A. Bitter iridoid glucoside from the fruit of Lonicera caerulea. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1989;24:512–513. doi: 10.1007/BF00598552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kucharska A.Z., Sokół-Łętowska A., Szumny A., Misztal K. Iridoids and phenolic compounds of honeysuckle fruits. In: Bogucka-Kocka A., Szymczak G., Kocki J., Sowa I., editors. Plant—The Source of Research Material, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference and Workshop, Lublin, Poland, 16–18 October 2013. Polihymnia; Lublin, Poland: 2013. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kucharska A.Z., Sokół-Łętowska A., Piórecki N., Klymenko S., Grygorieva O. Iridoids and anthocyanins of cornelian cherry fruits (Cornus mas L.) and blue honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea L. var. kamtschatica) In: Brindza J., Klymenko S., editors. Agrobiodiversity for Improving Nutrition, Health and Life Quality Part II. Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra; Nitra, Slovakia: 2015. pp. 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kucharska A.Z., Fecka I. Identification of iridoids in edible honeysuckle berries (Lonicera caerulea L. var. kamtschatica Sevast.) by UPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS/MS. Molecules. 2016;21:1157. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa R., Albergamo A., Pellizzeri V., Dugo G. Phytochemical screening by LC-MS and LC-PDA of ethanolic extracts from the fruits of Kigelia africana (Lam.) Benth. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016 doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1253080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitehead S.R., Bowers M.D. Iridoid and secoiridoid glycosides in a hybrid complex of bush honeysuckles (Lonicera spp., Caprifolicaceae): Implications for evolutionary ecology and invasion biology. Phytochemistry. 2013;86:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeram N.P., Momin R.A., Nair M.G., Bourquin L.D. Cyclooxygenase inhibitory and antioxidant cyaniding glycosides in cherries and berries. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:362–369. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park E., Kum S., Wang C., Park S.Y., Kim B.S., Schuller-Lewis G. Anti-inflammatory activity of herbal medicines: Inhibition of nitric oxide production and tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion in an activated macrophage-like cell line. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2005;33:415–424. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05003028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizgier P., Kucharska A.Z., Sokół-Łętowska A., Kolniak-Ostek J., Kidoń M., Fecka I. Characterization of phenolic compounds and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of red cabbage and purple carrot extracts. J. Funct. Foods. 2016;21:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alesci A., Cicero N., Salvo A., Palombieri D., Zaccone D., Dugo G., Bruno M., Vadala R., Lauriano E.R., Pergolizzi S. Extracts deriving from olive mill waste water and their effects on the liver of the goldfish Carassius auratus fed with hypercholesterolemic diet. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014;28:1343–1349. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.903479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucharska A.Z., Szumny A., Sokół-Łętowska A., Piórecki N., Klymenko S.V. Iridoids and anthocyanins in cornelian cherry (Cornus mas L.) cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015;40:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2014.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner A., Chen S.N., Nikolic D., van Breemen R., Farnsworth N.R., Pauli G.F. Coumaroyl iridoids and a depside from cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:253–258. doi: 10.1021/np060260f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juadjur A., Winterhalter P. Development of a novel adsorptive membrane chromatographic method for the fractionation of polyphenols from bilberry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:2427–2433. doi: 10.1021/jf2047724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan C.-S., Zhang Q., Xie W.-D., Yang X.-P., Jia Z.-J. Iridoids from Pedicularis kansuensis forma albiflora. Pharmazie. 2003;58:428–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sridhar C., Subbaraju G.V., Venkateswarlu Y., Venugopal R.T. New acylated iridoid glucosides from Vitex altissima. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:2012–2016. doi: 10.1021/np040117r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guimarães R., Barros L., Dueñas M., Carvalho A.M., Queiroz M.J.R.P., Santos-Buelga C., Ferreira I.C.F.R. Characterisation of phenolic compounds in wild fruits from Northeastern Portugal. Food Chem. 2013;141:3721–3730. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fecka I., Kucharska A.Z., Kowalczyk A. Quantification of tannins and related polyphenols in commercial products of tormentil (Potentilla tormentilla) Phytochem. Anal. 2015;26:353–366. doi: 10.1002/pca.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei S., Chi H., Kodama H., Chen G. Anti-inflammatory effect of three iridoids in human neutrophils. Nat. Prod. Res. 2013;27:911–915. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2012.668687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sozański T., Kucharska A.Z., Szumny A., Magdalan J., Bielska K., Merwid-Ląd A., Woźniak A., Dzimira S., Piórecki N., Trocha M. The protective effect of the Cornus mas fruits (cornelian cherry) on hypertriglyceridemia and atherosclerosis through PPARα activation in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:1774–1784. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sozański T., Kucharska A.Z., Rapak A., Szumny D., Trocha M., Merwid-Ląd A., Dzimira S., Piasecki T., Piórecki N., Magdalan J., et al. Iridoid-loganic acid versus anthocyanins from the Cornus mas fruits (cornelian cherry): Common and different effects on diet-induced atherosclerosis, PPARs expression and inflammation. Atherosclerosis. 2016;254:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinda B., Debnath S., Harigaya Y. Naturally occurring secoiridoids and bioactivity of naturally occurring iridoids and secoiridoids. A review, part 2. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007;55:689–728. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graikou K., Aligiannis N., Chinou I.B., Harvala C. Cantleyoside-dimethyl-acetal and other iridoid glucosides from Pterocephalus perennis—Antimicrobial activities. Z. Naturforschung C. 2002;57:95–99. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-1-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma W., Wang K.J., Cheng C.S., Yan G.Q., Lu W.L., Ge J.F., Cheng Y.X., Li N. Bioactive compounds from Cornus officinalis fruits and their effects on diabetic nephropathy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:840–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du W., Cai H., Wang M., Ding X., Yang H., Cai B. Simultaneous determination of six active components in crude and processed Fructus Corni by high performance liquid chromatography. J. Pharm. Biomed. 2008;48:194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou L.L., Liu Z.-Q., Wu G.-G., Song F.-R., Liu S.-Y. Analysis on iridoid glycosides in crude and processed extracts from Cornus officinals by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Acta Chim. Sin. 2008;24:2712–2716. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng S., West B.J., Jensen C.J. UPLC–TOF-MS characterization and identification of bioactive iridoids in Cornus mas fruit. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/710972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mehrotra R., Singh C., Popli S.P. Isolation of secoxyloganin from Lonicera japonica and its conversion into secologanin. J. Nat. Prod. 1988;51:319–321. doi: 10.1021/np50056a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo A.L., Chen L.M., Wang Y.M., Liu X.Q., Zhang Q.W., Gao H.M., Wang Z.M., Xiao W., Wang Z.Z. Influence of sulfur fumigation on the chemical constituents and antioxidant activity of buds of Lonicera japonica. Molecules. 2014;19:16640–16655. doi: 10.3390/molecules191016640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen S.R., Klaer A., Nielsen B.J. Loniceroside (secologanin) in Cornus officinalis and C. mas. Photochemistry. 1973;12:2064–2065. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)91544-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ochmian I., Skupien K., Grajkowski J., Smolik M., Ostrowska K. Chemical composition and physical characteristics of fruits of two cultivars of blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.) in relation to their degree of maturity and harvest date. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobo. 2012;40:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y., Zhu J., Meng X., Liu S., Mu J., Ning C. Comparison of polyphenol, anthocyanin and antioxidant capacity in four varieties of Lonicera caerulea berry extracts. Food Chem. 2016;197:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sosnowska D., Podsędek A., Kucharska A.Z., Opęchowska M., Koziołkiewicz M., Redzynia M. Comparison of in vitro anti-lipase and antioxidant activities, and composition of commercial chokeberry juices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016;242:505–515. doi: 10.1007/s00217-015-2561-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Justesen U., Knuthsen P., Leth T. Quantitative analysis of flavonols, flavones, and flavanones in fruits, vegetables and beverages by high-performance liquid chromatography with photo-diode array and mass spectrometric detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 1998;799:101–110. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(97)01061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]