Abstract

This study assessed the association between ethnicity, religious service attendance (RSA), and acculturation with posttraumatic growth (PTG) in a diverse sample of 235 childhood cancer survivors (CCS). PTG scores were estimated for each ethnicity, and by level of RSA and acculturation. There was a significant curvilinear relationship (inverted U) between RSA and PTG, such that moderate levels of RSA were associated with highest PTG scores. Hispanics reported the highest PTG, and both Hispanic and Anglo cultural orientation were significantly positively associated with PTG. CCS with high or low frequency of RSA as well as Hispanic CCS who lack a strong sense of cultural identity may benefit from targeted efforts to promote psychosocial adaptation in the aftermath of cancer.

Keywords: Pediatric, Survivorship, Minorities, Posttraumatic growth, Acculturation, Religiosity, Resiliency

Survivors of child and adolescent cancers experience challengesunique to their developmental phase,such as minimized social opportunities with peers andacademic delays1. Despite these challenges, survivors often report positive psychosocial changesas a result of their cancer experience2. These changes, referred to as posttraumatic growth (PTG), may include reassessed priorities, improved relationships, and an increased sense of meaning in one’s life3. PTG has been positively associated with health promoting behaviors, such as seeking disease-specific medical follow-up care 4 and decreased participation in risky behaviors such as substance use 5.

Numerous factors are associated with PTG among cancer survivors, includingsociodemographiccharacteristics. For example, adult African American and Hispanic cancer survivors report higher levels of PTG than non-Hispanic whites6. Although studies have assessed PTG (or similar constructs such as benefit finding, the perception of positive changes as a result of challenging experiences) among adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer, this literaturetends to consist largely of non-Hispanic whitesamples2,7. Moreresearch is needed on younger survivors among racial/ethnic minorities.

Cultural factors may explain some of the racial/ethnic variation in PTG. For example, Latinocultures may emphasize individuation from the family at a later age, while maintainingcloseness with one’s family, which is a major source of social support among young adultsand can contributeto psychosocial and physical health 8,9. Acculturation refers to cultural changes experienced by immigrants in a new cultural context. This is a bi-dimensional process whereby an individual’s orientation toward the dominant culture and his/her heritage culture may be independent; that is, strong orientation toward one culture does not necessarily indicate less orientation toward the other 10. Cultural identification may impact perception of and adjustment to illness and should be considered when assessing psychosocial health outcomes among diverse populations 11.For example, in a multiethnic sample of young adults, ethnic identity was associated with resiliencyafter other(non-cancer) childhood stressors12. Arpawong and colleagues found no differences in PTG by ethnicity alone, but when including language spoken at home (one aspect of acculturation), Hispanics who spoke English in the home reported lower levels of PTG than did their non-Hispanic white or Hispanic/Spanish-speaking counterparts 13. However, language spoken at home is just one component of acculturation, so broader measures need to be considered.Anglo (non-Hispanic white American) orientation among Hispanic adolescents has been positively associated with depression 14,which has been negatively correlated with PTG13,suggesting thatAnglo orientation may not be supportive of mental health among Hispanic youth.

Aspects of religiositymay alsoinfluence psychologicalresponses to traumatic health events.Further, there could be a reciprocal relationship between religiosity and PTG. For example, pre-trauma religiosity may be associated increased willingness to process traumatic events and address questions of personal meaning;likewise, traumatic experiences can lead individuals to seek out religion as a means of coping 15.Thus, religious individuals may be characterized by an increased readiness to confront existential questions in the face of difficulty, which underlies the development of PTG 16. In one study, religiosity was positively associated with PTG among adult breast cancer survivors6.It is unclear whether religiosity has a similar relationship with PTG among childhood cancer survivors (CCS).

This study examineddifferences in PTG by ethnicity, acculturation, and religious service attendance(RSA) (one aspect of religiosity17) among CCS.It was hypothesized that PTG would be highest among Hispanic participants, would be positively associated with Hispanic acculturation and RSA, and would be negatively associated with Anglo acculturation.

METHODS

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURES

Participants were recruited to participate in Project Forward, a study ofhealth-related risk and protective factors among CCS4. CCS who were diagnosed with cancer at age 18 or younger, were selected from the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance Program (CSP) (the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry for Los AngelesCounty). Additional selection criteria included being diagnosed between 2000–2007 at two major children’s hospitals in LA County, and who were between 14–25 years of age at the time the study was conducted in 2009. All cancer types were included except for Hodgkin Lymphoma because they were included in another registry-based study and, in order to reduce patient burden, the registry does not permit multiple studies to contact a patient during a given year.

Treating physicians of all sampled CCS were informed of the study by letter and given the opportunity to deny permission to contact their patient if they felt it would be inappropriate for any reason (though none requested exclusion). Surveys and study information were mailed to participants in English or Spanish (for those with Spanish surnames), with the additional option to complete the survey online or over the phone. Materials were mailed directly to CCS who were 18 or older at the time of the study. An introductory letter contained the elements of informed consent, but a signed consent form was not required. For those who were under 18, materials were mailed to their parents who provided written consent for their child to participate. In addition the child signed an assent form. Follow-up calls were made to non-respondents and second packets/reminder post cards were sent when needed. Participants received $20 and entry into a lottery for a $300 prize for completing the survey. All study procedures were approved by the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, California Cancer Registry, and by human subjects committees at the University of Southern California, CHLA, and Miller Children’s Hospital.

The final sample consisted of 235 participants. 27 responded to the online survey, 4 completed the survey via telephone, and the rest completed a mailed-in paper survey. This represented a 50% total response rate (which is higher than other cohorts of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors that included more recently diagnosed participants, which would result in more recent and reliable registry contact information)28. The participation rate (excluding ineligible cases that were never reached through any recruitment efforts) was 61%.

MEASURES

Demographic information including age, sex, and age at diagnosis, as well as treatment intensity were obtained from the cancer registry. Ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, Other) was self-reportedin the survey.

Treatment Intensity

Treatment intensity was calculated using the Intensity of Treatment Rating Scale 2.0 (ITR-2), which uses cancer registry data and medical chart reviews (including cancer type and stage of disease) to categorize cases into four levels of treatment intensity: 1=least intensive (e.g., surgery only), 2=moderately intensive (e.g., chemotherapy or radiation), 3=very intensive (e.g., two or more treatment modalities), 4=most intensive (e.g., relapse protocols) 18. This measure was validated using two sets of pediatric oncologists external to the institution that developed the scale. Additionally, inter-rater reliability for 12 patients of varying treatment intensities was assessed by a third group of raters, revealing high agreement (median agreement r=0.87)18.

Posttraumatic growth

A10-item short form 19of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) by Tedeschi and Calhoun20 was used to measure PTG, with simplified language for younger respondents. Participants were prompted to indicate the degree to which change was experienced as a result of having had cancer in various domains, such as”I changed my priorities about what is important in life,” “I have a greater appreciation for the value of my own life,” “I have a greater sense of closeness with others,” and “I discovered that I’m stronger than I thought I was.” Possible responses range from 1=“did not experience any change” to 6=“very great degree” of change.However, two items in this inventory addressaspects of spirituality or religiosity and since an aspect of religiosity (RSA) was an explanatory variable of interest in this study, these items were dropped from the total PTG score in multivariable analyses, resulting in a total of 8 items (total score range: 8–48). The summed score across these 8 items was used in all multivariable analyses, with higher scores indicating higher levels of PTG. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 for thefull scale including the spirituality/religiosity items, and 0.88 when excluding those items.

Acculturation

If a respondent self-identified as Hispanic they were directed to respond to a 13-item measure of acculturation, a shortened version of theAcculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II by Cuellar, Arnold, and Maldonado 21(the word “Mexican” was changed to “Hispanic” to be more broadly applicable). This shortened scale was taken from a larger cohort study of Latino adolescents in Los Angeles County22. Questions about orientation toward each culture (Hispanic and Anglo) are asked separately, based on the conceptualization of acculturation as a bidimensional process10. The shortened scale in this study included items focused primarily on language and behavioral aspects of acculturation such as “I enjoy speaking Spanish”, “I write letters in English”, “I enjoy Spanish language TV”, or “My friends are of Anglo or White origin”.Responses ranged from 1- “Not at all” to 5- “Almost always/extremely often.” Possible range of the summary scores were 6–30 (based on 6 items) for the Hispanic subscale and 6–35 (based on 7 items) for the Anglo subscale. Cronbach’s alpha for the Hispanicand Anglo subscales from the abbreviated scale was 0.92 and 0.68, respectively.

Religious service attendance

Attendance was measured with a single item,”how often do you attend religious services?”, with answers ranging from 0=never, 1=every few years, 2=several times a year, 3=2–3 times a month, 4=at least once a week, or don’t know. For analysis, “Don’t know” was grouped with the lowest category.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Descriptive statistics were calculated for PTG and each explanatory variable. PTG was negatively skewed and variable transformation (e.g. logarithm, cubed, inverse) was unable to correct for violated assumptions of linear regression. Therefore, ordinal logistic regression (proportional odds) was used in analyses, an approach that has been used previously when analyzing PTG among CCS 7. A likelihood ratio test indicated the proportional odds assumption was met (H0=explanatory variables display a consistent odds ratio (OR) across each interval of the outcome variable, p=0.86).

The association between continuous explanatory variables (RSA, acculturation, age at diagnosis)and PTG was assessed using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS)23, a desirablemethod because it tends to follow the data. These diagnostics demonstrated that there was a linear relationship between all explanatory variables and PTG except for religiosity, for which there appeared to be a curvilinear relationship;therefore,a quadratic term for this variable was added to the multivariable models. Acculturation was examined only among Hispanics in a separate model, which included the Hispanic and Anglo subscales as independent variables.

Multivariable models included covariates (age at diagnosis, treatment intensity, sex) that were chosen a priori based on relevance to PTG among CCS, as established in previous literature 2,13,24. Language in which survey was completed was not included as a covariate because only 6 participants completed the survey in Spanish. The dependent variable was PTG (ordinal categories determined by quartiles), and independent variables included ethnicity, RSA, and the Hispanic and Anglo acculturation subscales.The interaction of Hispanic and Anglo orientation was alsotested to explorethe joint effect on PTG, given that biculturalism (high Hispanic orientation and high Anglo orientation) has been associated with health outcomes 25.In order to provide meaningful and interpretable results, we estimatedprobabilities of reportingthe highest quartile PTG score (scores ≥ 44) for variables that were significant at the p<0.05 level, which were calculatedusing the estimates from each multivariable analysis by simulation using 1000 randomly drawn sets of estimates from a sampling distribution with the mean equal to maximum likelihood point estimates, variance equal to the variance-covariance matrix of the estimates, and covariates setat their mean values26. Listwise deletion resulted in 21 missing across all variables for a total sample size of 214 in the multivariable model including all subjects and 112 in the Hispanic-only model. All analyses were performed using Stata version 1427.

RESULTS

Characteristics of respondents and non-respondents were compared using registry data and no differences were found with respect to current age (p=.65), age at diagnosis (p=.28), or ethnicity (p=.71), although females were more likely to respond than males (56.4% vs. 44.8%; p<.05).Half the sample was female andjust over half were Hispanic(Table 1). PTG scores ranged from 8–48with a median of 40. On each item of the PTG, over half the sample reported at least a moderate positive change.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| N (%) | Mean PTG (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 116 (49.4) | 37.7 (8.5) |

| Female | 119 (50.6) | 38.7 (7.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 132(56.2) | 39.9 (7.7) |

| White | 62(26.3) | 35.3 (8.1) |

| Othera | 41(17.5) | 38.0 (7.5) |

| Treatment intensity | ||

| Least | 22 (9.4) | 35.9 (9.5) |

| Moderate | 77 (32.9) | 38.4 (8.9) |

| Very | 105 (44.9) | 38.7 (7.3) |

| Most | 30 (12.8) | 38.3 (7.0) |

| Religious service attendance | ||

| Never/don’t know | 43(18.4) | 37.9(7.7) |

| Every few years | 30(12.8) | 39.8(8.0) |

| Several times a year | 68(29.1) | 39.2(8.1) |

| 2–3 times p/month | 33(14.1) | 38.3(6.8) |

| At least once p/week | 60(25.6) | 36.7(8.7) |

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Age at survey | 19.8(2.8) | 15–25 |

| Age at diagnosis | 12.3(3.0) | 5–19 |

| Hispanic orientationb | 19.01(6.7) | 6–30 |

| Anglo orientationc | 29.3(3.8) | 16–35 |

Other=American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander;

Mean of 6 items;

Mean of 7 items

MULTIVARIABLE ANALYSES

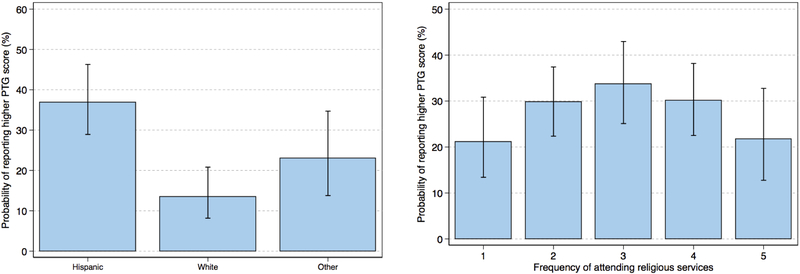

In themultivariable model including all participants, non-Hispanic whiteshadsignificantly lowerPTGscores and compared to Hispanics (OR=0.25, 95%CI: 0.13–0.45). The probability of falling into the highest category of PTG was37% (95%CI: 28%−45%) among Hispanics, compared to 14% for non-Hispanic whites(95%CI: 8%−21%) and 23% for Other (95%CI: 13%−36%)(Figure 1).RSA was also significantly associated with PTGas either a linear (ORlinear term=1.99, 95%CI: 1.12–3.53) or quadratic (i.e., curvilinear, inverted U) term (ORquadratic term=0.84, 95%CI: 0.73–0.97);the probability of reporting a highest quartile PTG score was21% (95%CI: 13%−31%) for those who never attended religious services or didn’t know, 30% (95%CI: 22%−37%) for those who attended every few years, 34% (95%CI: 24%−43%) for those who attended several times a year, 30% (95%CI: 23%−38%) for those who attended 2–3 times a month, and 22% (95%CI: 13%−33%) for those who attended at least once a week(Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Estimated probability of reporting highest PTG scores, by ethnicity and religiosity

Figure 2.

Estimated probability of reporting highest PTG scores, by acculturation subscale score

In the multivariable model restricted to Hispanics, Hispanic and Anglo acculturation were each positivelyassociated with PTG (ORHispanic=1.96, 95%CI: 1.37–2.81; ORAnglo=3.07, 95%CI: 1.52–6.20) (Figures 3a&b), as was the interaction of those terms when added to the model (OR=2.51, 95%CI: 1.20–5.26). To more clearly illustrate the interaction of Hispanic and Anglo cultural orientation (i.e. the bi-dimensional nature of acculturation) and itsrelationship with PTG, the estimated probability of falling into the highest category of PTG was calculated for an individual scoring low on bothacculturation subscales, high on both, or high on one and low on the other (Figure 3c).RSA wasnot significantly associated with PTG in the model among Hispanics only.

Figure 3.

Estimated probability of reporting highest PTG scores, by acculturation

DISCUSSION

The majority of CCS reported at least moderate levels of growth as a result of their cancer experience. This finding is consistent with prior work among less ethnically diverse CCS 213. PTG was more commonly reported among Hispanics (vs. non-Hispanic whites), which is also consistent withprevious research29. This difference was not confounded by age, gender, treatment intensity, or RSA. These differences may be associated with protective cultural aspects, such as the interdependency of family members, which is a prominent source of social support among Latinos30.

Among Hispanics, both Anglo and Hispanic orientationwere significantly positively associated withPTG(while estimated PTG was greatest for those with high orientation to both cultures, estimated PTG for an individual scoring high on orientation to just one culture was still greater than an individual scoring low on both).Previously,Arpawongand colleagues foundAnglo-oriented Hispanics reported significantly lower PTG,although this was in comparison to non-Hispanic whites, and only using language spoken at home as the acculturation indicator13. Our finding could indicate that having anystronger cultural identity is of greater importance in promoting successful psychosocial adaptation after childhood cancer than which particular culture one identifies with. That is, Hispanic CCS with lower levels of Hispanic and Anglo cultural identificationmay beless likely to experience positive growth following cancer. Having a strong sense of ethnic identity has been associated with self-efficacy and positive coping, feelings of belonging, and is thought to be protective of adverse mental health functioning 31, which may support the development of PTG. Previous work by Berry identified distinctstrategies that contribute to individuals’ acculturative typologies such that they may assimilate (adopt the dominant culture and distance from the culture of origin), separate (the opposite of assimilate), integrate (embrace both cultures) or be marginalized (lose all cultural affiliation)10.Though this method of categorization has been debated, various studies have verified the existence of these categories in unique samples and have found that those who integrate tend to have more positive health outcomes such as increased mental health, self-esteem and coping-efficacy25, supporting our findings.Future research should examine other culturallyinformed beliefs such as support seeking and perceptions of disease (e.g., fatalism) which could also impact growth and wellbeing in the aftermath of a traumatic health event 29.

Religiosityiscommonly beneficial in times of distress,likely because of the sense of meaning and hope offered to those who believe in a higher power 32. However, our findings indicate that one aspect of religiosity, RSA,had an inverse-U relationship with PTG, with the highest PTG scores at moderate levels. Relevant characteristicspreviously associated with greater PTG include openness to religious change 33 and deliberate reflection34. Thus, a potential explanation for decreased PTG among those with the highest levels/lowest levels of RSA could be cognitive rigidity 35, which may inhibit openness and the willingness to contemplate one’s experiencethat is needed for the development of PTG33,34. Moreover, the participants who spent the most time in religious services (and thus in the context of a like-minded community)may have employed more negative religious coping, whichmay becharacterized by an ominous view of the world, interpreting cancer as a punishment from God,and/or interpersonal religious discontent36. Negative religious coping is associated with psychological distress 37, which is negatively associated with PTG among CCS38. However, these potential explanations are speculative and may differ from previous studies due to differences in measurement.Studies with more detailed assessments of religiosity and related interpretations of negative life events are needed, including measuresof intrinsic versus extrinsic religiosity, which have been shown to differentially impact health outcomes 39.

While previous interventions have primarily targeted the reduction of maladaptive responses towards the cancer experience, emerging interventionshave begun to address the cultivation of resiliency and positive adaptation40. PTG has been associated with physical health as well as quality of life among cancer patients 41, and may be an important target for supporting the health and wellbeing of CCS. Elucidating potential facilitators and inhibitors of PTG may help identify CCS in greatest need of support services. The associations between PTG and the ethnicity and cultural factors in this study suggest demographic differences in resilience, consistent with previous findings 13,24.Future research is needed to examine specific cultural constructs (e.g. fatalism, familism) that can facilitate the development of PTG.

Supporting the development of PTG can includeinterventions that incorporate positive aspects of religious coping for CCS who identify religion as an important part of their lives.Specifically, interventions may aim topromote a sense of meaningfrom the cancer experience by encouragingsurvivorsto draw from the meaning derived from their faith42.A Meaning-Making intervention (MMi),designed to facilitate the search for meaning following a cancer diagnosis,has been tested in a randomized controlled study among ovarian cancer patients showing an improvedsense of meaning, and a trend toward greater existential well-being in the intervention group 43. Similar interventions may be useful for targeting facilitators of PTG among adolescent and young adult CCS. Other components of positive religious coping that may be modifiable intervention targets include seeking spiritual support or using religious or spiritual practices such as prayer to manage stress 42,44.

This study has several limitations. The PTG scale used in this study did not capture negative change, only allowing for a participant to indicate “no change” at a minimum, and may not have captured the full range of experiences. However, the answer format used in this study has been used previouslywhen studying PTG among CCS 4. The 50% response rate may also be a limiting factor with regard to the representativeness of the CCS population in Los Angeles County. While comparisons of demographic factors between responders and non-responders indicated that only gender differed significantly between the groups, selection bias may still pose a threat to external validity. Additionally, RSA captures just oneaspect of religiosity and does not representthe psychological, cognitive, or emotional factors associated withreligion45. More comprehensive scales should explore associations with religiosity as a whole, including other dimensions such as religious views and impact of religious beliefs on the self 46. Spirituality, another construct distinct from RSA and religiosity, may also be uniquely associated with PTG and should also be examined in future studies.The Anglo orientation subscale had low internal consistency in this sample, so results should be interpreted with caution.Moreover, the acculturation findings may not generalize to non-Hispanic white CCS given that the scale used in the present study was specific to Hispanics. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes causal inference.

CONCLUSION

The majority of CCS in this study reported experiencing PTG following their cancer experience. Among Hispanics, greater orientation toward either the Hispanic or Anglo culture was positively associated with PTG, a novel finding among this population suggesting that Hispanic CCS who do not exhibit strong orientation toward any/either culture are less likely to report PTGand may benefit from more targeted efforts to promote psychosocial adaptation in the aftermath of cancer. Contrary to previous studies, a curvilinear relationship was found between RSAand PTG, whichsuggests that moderate levels of church attendance (vs. high or low) may allow for the highest reporting of PTG. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore causality as well as mechanisms between these factors and PTG among CCS, with more detailed assessments of cultural identity and religious/spiritual beliefs/practices. Improved understanding of these potential facilitators of PTG can inform interventions aimed at improving the survivorship experience of CCS.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Whittier foundation (grant number 1R01MD007801) from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; the National Cancer Institute (grant numbers P30CA014089, T32CA009492). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.D’Agostino NM, Edelstein K. Psychosocial Challenges and Resource Needs of Young Adult Cancer Survivors: Implications for Program Development. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2013;31(6):585–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barakat LP, Alderfer MA, Kazak AE. Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2006;31(4):413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15(1):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milam JE, Meeske K, Slaughter RI, et al. Cancer-related follow-up care among Hispanic and non-Hispanic childhood cancer survivors: The Project Forward study: Follow-Up Care Among Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2015;121(4):605–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arpawong TE, Tobin J, Sussman S, & Milam JE Positive psychological growth and health-related behaviors: A systematic review. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellizzi KM, Smith AW, Reeve BB, et al. Posttraumatic Growth and Health-related Quality of Life in a Racially Diverse Cohort of Breast Cancer Survivors. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(4):615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klosky JL, Krull KR, Kawashima T, et al. Relations between posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Health Psychol. 2014;33(8):878–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roche KM, Caughy MO, Schuster MA, Bogart LM, Dittus PJ, Franzini L. Cultural Orientations, Parental Beliefs and Practices, and Latino Adolescents’ Autonomy and Independence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(8):1389–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katiria Perez G, Cruess D. The impact of familism on physical and mental health among Hispanics in the United States. Health psychology review. 2014;8(1):95–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry JW. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez A. Acculturation, Health Literacy, and Illness Perceptions of Hypertension among Hispanic Adults. Journal of transcultural nursing : official journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society / Transcultural Nursing Society. 2015;26(4):386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clauss-Ehlers CS, Yang Y-TT, Chen W-CJ. Resilience from Childhood Stressors: The Role of Cultural Resilience, Ethnic Identity, and Gender Identity. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy. 2006;5(1):124–138. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arpawong TE, Oland A, Milam JE, Ruccione K, Meeske KA. Post‐traumatic growth among an ethnically diverse sample of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psycho‐Oncology. 2013;22(10):2235–2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, Gender, Depression, and Cigarette Smoking Among U.S. Hispanic Youth: The Mediating Role of Perceived Discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(11):1519–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer FC, Blazer DG, Koenig HG. Religious and Spiritual Factors and the Consequences of Trauma: A Review and Model of the Interrelationship. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2008;38(4):507–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falsetti SA, Resick PA, Davis JL. Changes in Religious Beliefs Following Trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(4):391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber S, Huber OW. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions. 2012;3(4):710–724. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werba BE, Hobbie W, Kazak AE, Ittenbach RF, Reilly AF, Meadows AT. Classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment protocols: the intensity of treatment rating scale 2.0 (ITR-2). Pediatric blood & cancer. 2007;48(7):673–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, et al. A short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2010;23(2):127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuellar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A Revision of the Original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17(3):275–304. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unger JB. Cultural Influences on Substance Use Among Hispanic Adolescents and Young Adults: Findings From Project RED. Child Development Perspectives. 2014;8(1):48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleveland WS. Robust Locally Weighted Regression and Smoothing Scatterplots. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1979;74(368):829–836. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zebrack BJ, Stuber ML, Meeske KA, et al. Perceived positive impact of cancer among long‐term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Psycho‐Oncology. 2012;21(6):630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bulut E, Gayman MD. Acculturation and Self-Rated Mental Health Among Latino and Asian Immigrants in the United States: A Latent Class Analysis. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2016;18(4):836–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King G, Tomz M, Wittenberg J. Making the Most of Statistical Analyses: Improving Interpretation and Presentation. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44(2):347–361. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan THM, et al. Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE Study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011;5(3):305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kent EE, Alfano CM, Smith AW, et al. The Roles of Support Seeking and Race/Ethnicity in Posttraumatic Growth Among Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2013;31(4):393–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almeida J, Molnar BE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(10):1852–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greig R Ethnic Identity Development: Implications for Mental Health in African-American and Hispanic Adolescents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2003;24(3):317–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss T, Berger R. Posttraumatic Growth in U.S. Latinos. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc:113–127. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calhoun LG, Cann A, Tedeschi RG, McMillan J. A correlational test of the relationship between posttraumatic growth, religion, and cognitive processing. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2000;13:521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stockton H, Hunt N, Joseph S. Cognitive processing, rumination, and posttraumatic growth. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24(1):85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen MJ, Yelderman LA, Haggard MC, Rowatt WC. Disentangling the belief in God and cognitive rigidity/flexibility components of religiosity to predict racial and value-violating prejudice: A Post-Critical Belief Scale analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54(3):389–395. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. The Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37(4):710. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zwingmann C, Wirtz M, Müller C, Körber J, Murken S. Positive and Negative Religious Coping in German Breast Cancer Patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(6):533–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gianinazzi ME, Rueegg CS, Vetsch J, et al. Cancer’s positive flip side: posttraumatic growth after childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(1):195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Power L, McKinney C. The Effects of Religiosity on Psychopathology in Emerging Adults: Intrinsic Versus Extrinsic Religiosity. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53(5):1529–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haase JE. The Adolescent Resilience Model as a Guide to Interventions. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2004;21(5):289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Posttraumatic Growth Following Cancer: Links to Quality of Life. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25(5):567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds N, Mrug S, Wolfe K, Schwebel D, Wallander J. Spiritual coping, psychosocial adjustment, and physical health in youth with chronic illness: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychology Review. 2016;10(2):226–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henry M, Cohen SR, Lee V, et al. The Meaning-Making intervention (MMi) appears to increase meaning in life in advanced ovarian cancer: a randomized controlled pilot study. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19(12):1340–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kristeller JL, Sheets V, Johnson T, Frank B. Understanding religious and spiritual influences on adjustment to cancer: individual patterns and differences. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34(6):550–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimitrova R, del Carmen Domínguez Espinosa A. Factorial Structure and Measurement Invariance of the Four Basic Dimensions of Religiousness Scale Among Mexican Males and Females. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dowling EM, Gestsdottir S, Anderson PM, von Eye A, Lerner RM. Spirituality, Religiosity, and Thriving Among Adolescents: Identification and Confirmation of Factor Structures. Applied Developmental Science. 2003;7(4):253–260. [Google Scholar]