Abstract

Introduction

In most countries health warnings have been on cigarette packs for decades. We explored adolescents’ perceptions of a health warning on cigarettes.

Methods

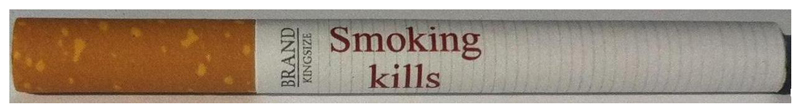

Data comes from the 2014 wave of a cross-sectional in-home survey with 11–16 year olds (N=1205) from across the UK, with participants recruited from the general population using random location quota sampling. Participants were shown an image of a standard cigarette, which displayed the warning ‘Smoking kills’, and asked whether they thought this would (not) put people off starting to smoke, (not) make people want to give up smoking, and whether all cigarettes should (not) have health warnings on them.

Results

Most (71%) thought that an on-cigarette warning would put people off starting, although this decreased with age. Never smokers were more likely than current smokers to think that it would put people off starting. Approximately half (53%) thought that an on-cigarette warning would make people want to give up smoking, with this higher for never smokers and experimenters/past smokers than for current smokers. Most (85%) supported a warning on all cigarettes. There was support among each smoking group, although this was higher for never smokers and experimenters/past smokers than for current smokers, and higher for those indicating that most of their close friends do not smoke than for those indicating that most of their close friends do smoke.

Conclusions

The perception among adolescents that an on-cigarette warning could deter smoking, and the high support for a warning on all cigarettes, warrants further research.

Introduction

It is argued that novel ideas and cost-effective interventions are needed to stop people taking up smoking and help smokers to quit.1 Myriad ideas have been proposed, focusing on the user (e.g. restricting sales by year born, prescription-only sales), the market (e.g. minimum pricing, advantaging cleaner nicotine products such as e-cigarettes over combustibles, quotas on tobacco manufacture and imports that are regularly reduced under a ‘sinking lid’) and institutional structures (e.g. a regulated market model or state takeover of tobacco companies to be managed with a health mandate).2 There have also been a number of product-focused proposals, including banning flavours, reducing nicotine levels, and increasing the pH level of cigarettes to make them more unpleasant to inhale.2 Another product-related proposal that has recently emerged concerns altering the appearance of cigarettes to make them more off-putting.3–5

As cigarettes continue to dominate the global nicotine market,6 if their appearance could be altered to make smoking less appealing, particularly to young people, then this would be of significant public health value. While research exploring dissuasive cigarettes is at an embryonic stage, three concepts have emerged: 1) unattractively coloured cigarettes;4 2) cigarettes displaying the ‘minutes of life’ lost due to smoking on the cigarette paper;3 and 3) cigarettes with the health warning ‘Smoking kills’ on the cigarette paper.5,7

Hoek and Robertson4 used qualitative research to explore young women smokers’ (N=22) perceptions of cigarettes, including ten unattractively coloured cigarettes. Dark green and brown cigarettes were perceived very negatively, making smoking appear dirty and reducing social acceptability, with participants reported to have difficulty reconciling these unappealing cues with the experience and identity they sought. Hassan and Shui3 conducted two studies with adult smokers (N=208) to explore their perceptions of a cigarette which displayed minutes of life lost on the cigarette paper. Quit intentions, assessed before and after participants were shown either an image of the cigarette (study 1) or an actual cigarette (study 2), significantly increased post-exposure. Two studies have explored perceptions of cigarettes displaying the warning ‘Smoking kills’ on the cigarette paper. The first, with young women smokers (N=49), found that for some it was viewed as a constant reminder of the health risks and off-putting due to the perceived discomfort of being observed by others smoking a cigarette displaying the words ‘Smoking kills’.5 The second study explored marketing and packaging experts’ (N=12) perceptions of a raft of novel ways to use the pack to communicate with consumers (e.g. pack inserts, cigarette packs that played audio health messages when opened, and on-cigarette warnings). The on-cigarette warning was considered a strong deterrent which, it was suggested, would confront smokers, put off non-smokers, signal to youth that it is neither cool nor intelligent to smoke, prolong the health message and serve as a continual reminder of the associated health risks.7

These findings, while limited to small samples, suggest that the cigarette is an important communications tool and that altering the appearance of cigarettes can influence how they are perceived. In this study we explored adolescents’ perceptions of whether an on-cigarette warning (‘Smoking kills’) would discourage uptake and encourage cessation, and level of support for having a health warning on all cigarettes.

Methods

Design and sample

Data comes from wave seven of the Youth Tobacco Policy Survey, a long-running in-home survey with 11-16 year olds. A market research company (FACTS International) was hired to recruit participants during August-September 2014. The fieldwork involved face-to-face interviews conducted in-home, by professional interviewers, accompanied by a self-completion questionnaire to gather more sensitive data on smoking behaviour. Parental and participant informed consent was secured prior to each interview.

A cross-sectional sample of 11–16 year-olds (N=1205) was drawn from households across the UK, using random location quota sampling, see elsewhere for more information on the design and sampling.8 Comparative census data for England and Wales indicate that the weighted sample was in line with national figures for gender and age9 as well as smoking prevalence among 11-15 year olds in England.10 Ethical approval was obtained from the Marketing Department Ethics Committee at the University of Stirling.

Measures

General information

Age, gender and smoking by mother, father, siblings (if any) and close friends was obtained. Social grade was determined by occupation of the chief income earner in the household.

Smoking status

Two items were used to assess smoking status. ‘Never smokers’ had never smoked a cigarette, not even a puff; ‘experimenters/past smokers’ had tried smoking or used to smoke; and ‘current smokers’ smoked at least one cigarette a week or smoked sometimes (but less than one a week). These definitions are consistent with national youth surveys in the UK.10

Perception of cigarette warnings

Participants were shown an image of a standard cigarette (cork filter, white cigarette paper) with the warning ‘Smoking kills’ printed in red on the cigarette paper (see Supplementary Figure 1) and asked “Can you tell me what you think about cigarettes having warnings on them”. Three items, each measured on a five-point semantic scale, were used to assess the perceived impact of cigarette warnings on initiation and cessation and also to gauge level of support; a) Would put people off starting to smoke (1) / Would not put people off starting to smoke (5); b) Would not make people want to give up smoking (1) / Would make people want to give up smoking (5) and c) All cigarettes should have a health warning on them (1) / No cigarettes should have a health warning on them (5). Item b) was reverse coded at the analysis stage so that a high score consistently reflected a negative reaction. These measures were developed and tested during the survey development stage, with six exploratory focus groups and 11 pilot interviews conducted with 11-16 year olds to ensure understanding and relevance of the measures.9

Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 21. Descriptive data were weighted to standardise across age and gender in order to better reflect the population of 11 to 16 year olds in the UK. Each of the three items was converted to a binary variable to examine the proportions who held positive perceptions (codes 1 and 2) versus those who held neutral or negative perceptions (codes 3 to 5). Bivariate analysis, using the chi-square test, was initially used to examine relationships between positive perceptions of on-cigarette warnings and smoking status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Response to warnings on cigarettes by smoking status (weighted)

| Total | Current Smoker | Experimenter /Past Smoker |

Never Smoker | Chi-square p valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | ||

| Would put people off starting to smoke (codes 1 and 2) | (844) | 71% | (42) | 47% | (95) | 64% | (690) | 75% | p<0.001 |

| Would put people off starting to smoke (1) | (648) | 55% | (28) | 32% | (68) | 46% | (539) | 58% | |

| (2) | (196) | 16% | (14) | 16% | (27) | 18% | (151) | 16% | |

| (3) | (159) | 13% | (17) | 19% | (18) | 12% | (117) | 13% | |

| (4) | (76) | 6% | (17) | 19% | (12) | 8% | (45) | 5% | |

| Would not put people off starting to smoke (5) | (110) | 9% | (13) | 14% | (24) | 16% | (71) | 8% | |

| Median | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Mean | 1.99 | 2.69 | 2.30 | 1.87 | |||||

| Standard Deviation | 1.33 | 1.45 | 1.50 | 1.26 | |||||

| Valid Nb (weighted) | 1190 | 88 | 148 | 924 | |||||

| Valid Nb (unweighted) | 1190 | 82 | 142 | 937 | |||||

| Would make people want to give up smoking (codes 1 and 2) | (620) | 53% | (28) | 32% | (73) | 49% | (507) | 56% | p<0.001 |

| Would make people want to give up smoking (1) | (402) | 34% | (12) | 13% | (39) | 26% | (344) | 38% | |

| (2) | (218) | 19% | (17) | 19% | (34) | 23% | (164) | 18% | |

| (3) | (267) | 23% | (31) | 36% | (38) | 25% | (188) | 21% | |

| (4) | (133) | 11% | (14) | 16% | (17) | 11% | (100) | 11% | |

| Would not make people want to give up smoking (5) | (153) | 13% | (14) | 16% | (21) | 14% | (115) | 13% | |

| Median | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |||||

| Mean | 2.50 | 3.03 | 2.65 | 2.43 | |||||

| Standard Deviation | 1.40 | 1.25 | 1.36 | 1.41 | |||||

| Valid Nb (weighted) | 1174 | 87 | 148 | 910 | |||||

| Valid Nb (unweighted) | 1174 | 81 | 142 | 922 | |||||

| All cigarettes should have a warning on them (codes 1 and 2) | (1007) | 85% | (45) | 51% | (114) | 77% | (822) | 89% | p<0.001 |

| All cigarettes should have a health warning on them (1) | (888) | 75% | (33) | 37% | (102) | 69% | (735) | 80% | |

| (2) | (119) | 10% | (13) | 14% | (12) | 8% | (87) | 9% | |

| (3) | (109) | 9% | (18) | 20% | (28) | 19% | (60) | 6% | |

| (4) | (34) | 3% | (12) | 14% | (4) | 3% | (17) | 2% | |

| No cigarettes should have a health warning on them (5) | (40) | 3% | (13) | 15% | (2) | 1% | (25) | 3% | |

| Median | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Mean | 1.50 | 2.55 | 1.59 | 1.39 | |||||

| Standard Deviation | 1 | 1.47 | 0.97 | 0.89 | |||||

| Valid Nb (weighted) | 1190 | 88 | 148 | 924 | |||||

| Valid Nb (unweighted) | 1191 | 82 | 142 | 937 | |||||

Chi-square test on the binary coded response to each item (codes 1 and 2 v codes 3, 4 and 5), by smoking status.

P-values are quoted for the weighted data but analysis run on unweighted data produced the same p values.

Missing cases (“Don’t know” and “not stated” responses) are excluded from the above table.

Three logistic regression models were then constructed to assess the relationships between positive perceptions of on-cigarette warnings and smoking status while controlling for other potential influences. The dependent variable for the first was perceptions of whether on-cigarette warnings would put people off starting to smoke: would put off (codes 1 to 2) vs. neutral/would not put off (codes 3 to 5). Control variables were entered, using the enter method, to control for the potential influence of demographic and smoking-related factors identified in past research as influencing youth smoking.11–13 These were: 1) parental and peer smoking; 2) demographics (age, gender and social grade), and 3) smoking status. Two more logistic regressions were run with the dependent variable perceptions of whether on-cigarette warnings would make people want to give up smoking (would make them want to give up (codes 1 and 2) vs. neutral/would not make people want to give up (codes 3 to 5)) and support for on-cigarette warnings (all cigarettes should have a health warning on them (codes 1 and 2) vs. neutral/no cigarettes should have a health warning on them (codes 3 to 5)). Logistic regressions were run on unweighted data as the models controlled for age and gender.

Results

Perceptions of on-cigarette warnings on uptake and cessation

Almost three-quarters (71%, n=844) thought that an on-cigarette warning would put people off starting to smoke (Table 1). Likelihood of perceiving that an on-cigarette warning would put people off starting to smoke decreased with age (AOR 0.89, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.97, p<0.01). Never smokers were more likely than current smokers to think that an on-cigarette warning would put people off starting (AOR 2.24, 95% CI 1.30 to 3.88, p<0.01), see Table 2, column A.

Table 2.

Logistic regression of association between views on warnings on cigarettes and smoking habits of social network, smoking status and demographics

| A. Would put people off starting to smoke 1 = Would put people off starting to smoke (821), 0 = Neutral / Would not (326) |

B. Would make people want to give up smoking 1 = Would make people want to give up smoking (607), 0 = Neutral / Would not (524). |

C. Support for health warnings on cigarettes 1 = All cigarettes should have a health warning on them (971), 0 = Neutral / Should not (176). |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Adj OR* |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

P | N | Ad OR* |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

P | N | Adj OR* |

95% CI Lower |

95% CI Upper |

P | |

| Close Friends Smoking | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.01 | ||||||||||||

| Majority do not smoke | 899 | ref | 886 | ref | 898 | ref | |||||||||

| Majority smoke | 116 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 1.29 | 0.37 | 115 | 0.99 | 0.63 | 1.57 | 0.97 | 116 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.78 | <0.01 |

| Not stated | 132 | 1.09 | 0.71 | 1.68 | 0.69 | 130 | 1.21 | 0.82 | 1.78 | 0.34 | 133 | 1.15 | 0.63 | 2.09 | 0.65 |

| Parental Smoking | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.71 | ||||||||||||

| Neither | 576 | ref | 564 | Ref | 576 | Ref | |||||||||

| Either or both | 468 | 0.80 | 0.60 | 1.07 | 0.14 | 463 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 1.21 | 0.57 | 467 | 1.11 | 0.75 | 1.62 | 0.61 |

| Not sure/not stated/no mum/dad | 103 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 104 | 0.77 | 0.50 | 1.19 | 0.24 | 104 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 1.58 | 0.63 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 571 | ref | 560 | Ref | 574 | Ref | |||||||||

| Female | 576 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 1.29 | 0.96 | 571 | 0.99 | 0.78 | 1.26 | 0.94 | 573 | 1.05 | 0.75 | 1.47 | 0.77 |

| Age | 114 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.97 | <0.01 | 1131 | 0.93 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 1147 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.08 | 0.53 |

| Social Grade | |||||||||||||||

| ABC1 | 465 | ref | 455 | Ref | 466 | Ref | |||||||||

| C2DE | 682 | 1.19 | 0.90 | 1.58 | 0.21 | 676 | 1.20 | 0.94 | 1.55 | 0.15 | 681 | 1.17 | 0.82 | 1.67 | 0.39 |

| Smoking status | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 81 | ref | 80 | Ref | 81 | Ref | |||||||||

| Experimenter/Past smoker | 140 | 1.62 | 0.90 | 2.90 | 0.11 | 140 | 2.20 | 1.20 | 4.04 | 0.01 | 140 | 2.52 | 1.35 | 4.71 | <0.01 |

| Never smoker | 926 | 2.24 | 1.30 | 3.88 | <0.01 | 911 | 2.67 | 1.51 | 4.72 | <0.01 | 926 | 4.91 | 2.70 | 8.92 | <0.001 |

| Test of model coefficients: χ2=45.21, df=9, p<0.001. Nagelkerke R2=0.06. Hosmer & Lemeshow χ2= 4.81, df=8, p=0.78. |

Test of model coefficients: χ2=30.10, df=9, p<0.001. Nagelkerke R2=0.04. Hosmer & Lemeshow χ2= 6.88, df=8, p=0.55. |

Test of model coefficients: χ2=76.96, df=9, p<0.001. Nagelkerke R2=0.11. Hosmer & Lemeshow χ2= 3.00, df=8, p=0.93. |

|||||||||||||

adjusted for all other variables in the model, Adj OR, adjusted odds ratio; ref, reference category; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Approximately half (53%, n=620) thought that an on-cigarette warning would make people want to give up smoking. Never smokers and experimenters/past smokers were more likely than current smokers to think that an on-cigarette warning would make people want to give up smoking (AOR 2.67, 95% CI 1.51 to 4.72, p<0.01 for never smokers; AOR 2.20, 95% CI 1.20 to 4.04, p<0.05 for experimenters/past smokers), see Table 2, column B.

Support for health warnings on cigarettes

The vast majority (85%, n=1007) thought that all cigarettes should have warnings on them (Table 1). Even among current smokers, half (51%, n=45) were supportive of warnings on all cigarettes. Participants who indicated that most of their close friends smoke were less likely than those who indicated that most of their close friends do not smoke to support warnings on all cigarettes (AOR 0.47, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.78, p<0.01), see Table 2, column C. Never smokers and experimenters/past smokers were more likely than current smokers to support warnings on all cigarettes (AOR 4.91, 95% CI 2.70 to 8.92, p<0.001 for never smokers; AOR 2.52, 95% CI 1.35 to 4.71, p<0.01 for experimenters/past smokers).

Discussion

As the manufactured cigarette has long been the most popular form of tobacco, and will likely dominate the global nicotine market for some time, it is surprising that its potential to be exploited to make smoking less attractive has been overlooked until recently. This is the first study to explore adolescents’ perceptions of dissuasive cigarettes, with the findings suggesting that altering the appearance of the cigarette, specifically via the inclusion of a health warning, may have a deterrent effect. While the perception that an on-cigarette warning would put people off smoking decreased with higher age and involvement with smoking, as smoking onset often begins in childhood the fact that more than seventy percent of participants perceived them to have a deterrent effect warrants further research. One possibility is that the presence of a warning on cigarettes is associated with an undesirable image, and as initiation is known to be strongly influenced by image,14 this acts as a deterrent.

A lower proportion of the sample (53%) thought that an on-cigarette warning would make people quit, with current smokers least likely to think that this was the case. That more young people believed that an on-cigarette warning would put people off starting to smoke than believed they would encourage quitting may, even at this early age, reflect the perceived difficulty of giving up. This would be consistent with tobacco industry documents, which explain that while smoking is intriguing to pre-teens and early teens, even by the age of 16 many who have adopted the habit regret doing so and feel unable to stop.15 This regret may also explain, at least in part, why half of current smokers supported a warning on all cigarettes. The very high level of support (85%) among the sample suggests that adolescents see potential value in this concept.

The study provides an insight into how cigarettes may be perceived by adolescents if they were to display a health warning. However, the novelty of the stimuli and forced exposure may have had an impact on responses. Similarly, socially desirable responding is a potential limitation, and the final sample included only a relatively small number of regular smokers. Cigarettes were also rated in the absence of packaging. While 11-16 year olds who experiment with smoking or who are smokers often access single cigarettes (whether via retailers, friends, family members or adults on the street),16 and therefore may not necessarily see the packaging as frequently as adult smokers,17 exposure to an on-pack warning may have an impact upon their response to an on-cigarette warning. Further research exploring youth perceptions of on-cigarette warnings, the reasons underlying these responses, and whether exposure to on-pack warnings would impact upon these perceptions, would be of value.

Implications.

Research on dissuasive cigarettes is at a nascent stage. This is the first study to explore how adolescents perceive a health warning (‘Smoking kills’) on cigarettes. Almost three-quarters of participants indicated that on-cigarette health warnings would deter people from starting to smoke, and 85% supported the inclusion of a warning on all cigarettes. While further research is clearly needed, these findings suggest that the inclusion of health warnings on cigarettes is considered appropriate by young people and may have a dissuasive effect.

Figure 1.

On-cigarette health warning

Funding

Funding was provided by Cancer Research UK

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors have no interests to declare.

References

- 1.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Yach F, Mackay J, Reddy KS. A tobacco-free world: a call to action to phase out the sale of tobacco products by 2040. The Lancet. 2015;385:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/SO140-6736(15)60133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDaniel PA, Smith EA, Malone RE. The tobacco endgame: a qualitative review and synthesis. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052356. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassan L, Shui E. No place to hide: two pilot studies assessing the effectiveness of adding a health warning to the cigarette stick. Tob Control. 2015;24:e3–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoek J, Robertson C. How do young adult female smokers interpret dissuasive cigarette sticks? J Social Marketing. 2015;5:21–39. doi: 10.1108/JSOCM-01-2014-0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moodie C, Purves R, McKell J, de Andrade M. Novel means of using cigarette packaging and cigarettes to communicate health risk and cessation messages: A qualitative study. Int J Mental Health Addiction. 2015;13:333–44. doi: 10.1007/s11469-014-9530-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksen MP, Mackay J, Schluger N, Gomeshtapeh FI, Drope J. The tobacco atlas. (5th ed) Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moodie C. Novel ways of using tobacco packaging to communicate health messages: Interviews with packaging and marketing experts. Add Res Theory. 2016;24:54–61. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2015.1064905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford A, Mackintosh AM, Bauld L, Moodie C, Hastings G. Adolescents’ awareness of e-cigarette marketing and perceptions of flavours: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Pub Health. 2016;61:215–24. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0769-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office for National Statistics. 2011 Census: Population and household estimates for England and Wales. 2012 http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/2011censuspopulationandhouseholdestimatesforenglandandwales/2012-07-16.

- 10.Fuller E. Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England in 2014. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amos A, Angus K, Bostock Y, Fidler J, Hastings G. A review of young people and smoking in England. York: Public Health Research Consortium; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul SL, Blizzard L, Patton GC, Dwyer T, Venn A. Parental smoking and smoking experimentation in childhood increase the risk of being a smoker 20 years later: the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study. Addiction. 2008;103:846–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo D-C, Huang Y. Systematic review of social network analysis in adolescent cigarette smoking behaviour. J Sch Health. 2012;82:21–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.BAT Collection. The vanishing media. 1978. Bates range 500062147/2159.

- 15.Pollay RW. Targeting youth and concerned smokers: evidence from Canadian tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2000;9:136–47. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong G, Glover M, Nosa V, Freeman B, Paynter J. Young people, money, and access to tobacco. N Z Med J. 2007;120:1267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker HM, Lee JGL, Ranney LM, Goldstein AO. Single cigarette sales: State differences in FDA advertising & labelling violations, 2014, USA. Nic Tob Res. 2016;18:221–6. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]