Abstract

Nightclubs are a setting in which young adults purposefully seek out experiences, such as drug use and alcohol intoxication that can expose them to physical harm. While physical harm occurs fairly frequently within clubs, many patrons have safe clubbing experiences. Further, not all patrons experience potential harms the same way, as there are differences in aggression and intoxication. In this article we draw on data from a research study in which we sought to better understand the role of social drinking groups in experiences of risk within nightclubs, as the majority of patrons attend with others. We collected data from 1,642 patrons comprising 615 social drinking groups as they entered and exited nightclubs in a major U.S. city. We focused on six experiences that might cause physical harm: alcohol impairment, alcohol intoxication, drug use, physical aggression, sexual aggression, and impaired driving. We aggregated patron responses across social groups and used latent class statistical analysis to determine if and how experiences tended to co-occur within groups. This analysis indicated there were five distinct classes which we named Limited Vulnerability, Aggression Vulnerability, Substance Users, Impaired Drivers and Multi-Issue. We assessed the groups within each class for distinctions on characteristics and group context. We found differences in the groups in each class, such as groups containing romantic dyads experienced less risk, while those groups with greater familiarity, greater concern for safety, and higher expectations for consumption experienced more risk. Group composition has an impact on the experiences within a club on a given night, in particular when it comes to risk and safety assessment.

Keywords: Concurrent risk, risk, young adults, alcohol, drugs, aggression

Introduction

Nightclubs are a context for experiences that health researchers typically view as risk behaviours (Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Voas, & Johnson, 2013). However, behaviours identified from a public health perspective may not be considered risky by the individuals involved (Zinn, 2015). Like other public music venues (Wiedermann, Niggli, & Frick, 2014), individuals purposely choose the nightclub context to engage in behaviours like drug and alcohol use even if they know that those experiences may lead to physical harm. Yet these risks are not experienced uniformly across all patrons. In this paper, we seek to better understand the ways in which nightclub experiences form constellations of potential risk among social groups who are going together to the nightclub. In addition, we consider elements related to the perception of safety of the context, such as group composition, familiarity, and expectations for behaviour. Thus, we focus on social groups in order to provide an understanding of the context in which subjective risk is assessed.

Risk-taking in Social Contexts

Risk in Nightclubs

Given the social nature of nightclubs (Johnson, Voas, & Miller, 2012; Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Johnson, & Voas, 2013), risk-taking by any one person has an outward ripple effect and the behaviours of one may affect many others. Exposure to risk occurs not just for that person, but also extends to their social group, as well as the other club patrons and staff, and even individuals outside the club. In determining subjective risk, an individual may consider high amounts of alcohol consumption to have worthwhile benefits (the physical pleasure of inebriation) relative to perceived uncertainty about the costs (becoming sick, passing out, making poor decisions) (Trimpop, 1994). Social group or societal risks may not be considered by an individual when pursuing risky behaviours. For instance, the individual’s social group may experience the costs because they feel required to provide aid/assistance or may be asked to leave the club. Societal risks include an individual’s unpleasant or aggressive behaviour directed toward others in or outside the club. Individuals may become a public nuisance or operate a vehicle while under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Clubs are locations where it is possible to have a safe experience with little chance of physical harm. Survey research indicates that the vast majority of patrons (85 %) do not report experiencing physical or sexual aggression while in the club (Miller, Bourdeau, Johnson, & Voas, 2015). In addition, an average of 25 % of patrons do not use any alcohol or drugs and only 28 % leave the clubs legally intoxicated (Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Voas, et al., 2013).

However, individuals who experience one form of risk can often experience multiple forms of risk. Public health research has focused on multiple “risk” experiences including alcohol and drug use, poly-drug use, alcohol/drug use and aggression, and leaving the club under the influence of alcohol or drugs as targets for prevention strategies (Johnson et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2015; Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Voas, et al., 2013; Voas, Johnson, & Miller, 2013). The experience of multiple risks can have a compounding effect in the potential for harm. Given the larger environment in which nightclub behaviours are situated, we feel it is important to also consider the assessment of risk within a given context and its relationship to experiences that may increase the likelihood of harm to the individual and others.

The social context of risk

In considering the nested nature of potential risk, we situated our thinking in a social-ecological approach (Gruenewald, 2007) to on-premise drinking locations, an approach which considers ways in which consumption is influenced by social factors such as:

Topology State, city, and local ordinances have a differential impact on both alcohol consumption and aggression (Bellis et al., 2008; Giancola, 2002) which can mediate the effect of drinking establishments on the larger environment

Context Management policies and staffing practices within a given club, such as a permissive attitude toward alcohol consumption, drink promotions, and staff demographics (Byrnes, Miller, Johnson, & Voas, 2014; Clapp, 2010; Graham & Homel, 2008; Green & Plant, 2007; Homel, Carvolth, Hauritz, McIlwain, & Teague, 2004; Ker & Chinnock, 2008; Macintyre & Homel, 1997; Roberts, 2009) can contribute to safety within the club

Agency Individual patrons’ social backgrounds, such as age and gender (Harford, Wechsler, & Muthen, 2003), or sexual orientation (Miller et al., 2015), have influence how much they drink (Graham, Osgood, Wells, & Stockwell, 2006) which in turn can contribute to involvement in aggression

Contacts Hosted event and patron characteristics result in potentially different interactions across and within social groups that impact risk behaviours. Intra-group influences can directly impact on alcohol consumption, with some drinking groups tending to consume too much alcohol (Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004; Neighbors, Lindgren, Knee, Fossos, & DiBello, 2011). Inter-group interactions may also increase risks, such as competition between male patrons for the attention of women (Graham, Wells, Bernards, & Dennison, 2010; Wells, Graham, & Tremblay, 2009). Social norms created by the collective social groups can also increase alcohol consumption (Cullum, O’Grady, Armeli, & Tennen, 2012a).

Social groups are an emerging focus of research within nightclub studies, given that the overwhelming majority of club patrons arrive with friends and these groups impact the individual’s experience, either increasing or decreasing, risk (Johnson, Voas, Miller, Bourdeau, & Byrnes, 2015; Johnson et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2015; Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Johnson, et al., 2013). Social groups can vary greatly and groups may or may not remain intact over multiple nights, thereby potentially changing the likelihood of an individual experiencing a specific vulnerability on any given night. Basic indicators of group composition, such as demographics, can influence potential risk in clubs (e.g., male gender (Benson, 2002; Krienert & Vandiver, 2009; Testa, Kearns-Bodkin, & Livingston, 2009; Wells et al., 2009; Wells, Neighbors, Tremblay, & Graham, 2011), younger age (Miller et al., 2015), and larger group size (Cullum, O’Grady, Armeli, & Tennen, 2012b; McClatchley, Shorter, & Chalmers, 2014)).

Behaviours amongst group members are also influential; groups choose more risky options when they are drinking (Sayette, Dimoff, Levine, Moreland, & Votruba-Drzal, 2012). Furthermore, the social group’s drinking prior to entering clubs and bars (‘preloading’) significantly impacts on an individual’s drinking later that same evening (Wells et al., 2015) and greater familiarity of group members can increase an individual’s experience of aggression (Johnson et al., 2015). Group norms such as the expectation for drinking that night, as well as larger discrepancies for drinking expectations, are risk factors for an individual’s experience of physical aggression (Miller et al., 2015). Miller et al. (2015) also found the social group’s assessment that they have a frequently drunk member significantly predicted an individual’s risk of experiencing sexual aggression while in the club. However, the picture is more complex. For example, investigations into the roles of individuals within groups indicate that taking the role of designated driver serves a protective effect on that individual’s drinking (Bourdeau, Miller, Johnson, & Voas, 2015; Lange, Johnson, & Reed, 2006).

Group composition and context then, can provide insight into subjective risk perception among nightclub patrons that can then have implications into their behaviour and lead them to underestimate the impact of their choices on others in the social context. We will examine how experiences and choices by patrons in nightclubs might co-occur in social groups, and then look for differences in social groups that might be contributing factors.

Identifying social groups and risk use

To identify a model for how nightclub experiences co-occur, we looked to person-centred analytic strategies in the study of individual substance use. Many studies of poly-substance use by adolescents employ latent class (cross-sectional) and latent profile (longitudinal) analysis (LCA/LPA) (Tomczyk, Isensee, & Hanewinkel, 2015) to investigate how behaviours cluster together. This approach is sensitive to individual patterns and allows for outcomes to be considered together in multiple forms. In nightclub patron research, two studies have used this approach to understand the intersection of risk experience as well as the ways in which these behaviours can differ in their dynamic. In one study, Ramo and colleagues (Ramo, Grov, Delucchi, Kelly, & Parsons, 2010) used latent class to categorise young adult (18–29) club patrons with regard to their polydrug use. They found three classes of drug users: ‘cocaine users’ (low use of drugs except cocaine); ‘wide-range’ (high use for many drugs and highest for meth); and ‘mainstream’ (low use for most drugs but high for ecstasy and cocaine). There were demographic differences amongst the classes as well. Similarly, Anderson and colleagues (2009) used interviews with 51 club patrons (average age 26) to create a typology of patrons who use drugs, examining motivations for clubbing and preferences in the type of music scene. They also found three classes: ‘drug sub-culture’ (those who attend clubs to participate in high levels of drug use), ‘commercial clubbers’ (those who attend clubs primarily for alcohol use), and ‘music connoisseurs’ (those whose current drug use is low but often have an extensive history of abuse).

Although research has focused on individuals in nightclubs in terms of experiences they have that could lead them to physical harm, those experiences have an effect on all members of the social group, not just the individual. Whilst one patron may have an uneventful evening with regard to their own personal behaviour and risk, that same individual may have had to break up a fight, fend off a harasser, take care of an ill friend, or drive someone home unexpectedly. Alternatively, there may be characteristics of the group that contribute to individuals’ assessment of subjective risk. The finding that familiarity among social groups can lead to increased risk indicates that might be the case. Either way, given the social nature of attending nightclubs, the focus on social groups is needed. In this article, we seek to understand the ways in which social groups in nightclubs vary in their constellation of ‘risk’ experiences. We further consider how groups in each constellation vary by social context.

Methods

We determined that a methodology that assesses all members of the social groups would give the best insight into the demographic composition, group dynamics, and risk experiences/behaviours. Our previous work utilised a sampling methodology which intercepted patrons as they entered and exited the club (Miller et al., 2009; Voas et al., 2006), providing immediacy to potentially risky experiences and behaviours. Because discrepancies between patron self-report and biological assessments of drug and alcohol use occur (Johnson, Voas, Miller, & Holder, 2009), we have continued to use biological measurements as the most accurate for determining precise levels of risk. Specifically, the use of biomarkers can identify individuals whose Breath Alcohol Content (BrAC) would meet the legal criteria for drink driving in the locality where data was collected.

We started by developing a list of clubs in San Francisco featuring events which attracted a minimum of 200 patrons on typical weekend evenings and approached all managers/owners. Of the 13 club managers/owners we approached, three did not agree to participate. Evening events reflected different types of electronic music (such as Industrial, House) and were promoted to attract different types of patrons (for example, Latinos, younger patrons [under 21], lesbian/ gay/ bisexual/ transgender). We collected data from patrons as they entered and exited 10 nightclubs for 71 different events in the San Francisco area from mid-June 2010 through mid-November 2012. Each club served as a research location a minimum of three nights and a maximum of ten.

Procedures

Consistent with our prior research (Miller, Byrnes, Branner, Johnson, et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2009; Voas et al., 2006) we established a research site proximal to the club entrance with a team of approximately eight research staff. We approached social groups, asking patrons if they would be willing to participate in an anonymous study on nightlife safety. Consistent with research using human subjects in the United States, research staff provided remuneration to participants (Permuth-Wey & Borenstein, 2009) totalling $30.00 ($10 at entrance and $20 at exit). Research staff escorted patrons to the research area where consent forms were read to participants and verbal consent was obtained. We made copies of the consent form available.

We issued patrons a wrist band with a unique identifier that allowed us to link entrance and exit data. This allows us to track changes through the evening, such as who was the designated driver or determine how much alcohol was consumed. In addition, this allowed us to link individuals within social groups and create group aggregate values. The wristbands also maintained anonymity for patrons. At entrance and at exit, we collected four types of data: brief verbal interview conducted by the research assistant; self-administered survey; oral assays for drug tests; and breathalyser tests for estimating blood alcohol concentration (BAC). Results from oral assays and breathalyser tests were not available in the field. If patrons reported planning to drive and reported being buzzed or intoxicated or were obviously drunk/drugged (assessment based upon observational skills training), the on-site supervisor followed established protocol that involved communicating with the group about alternative plans for ensuring safety (such as calling a cab/ride-service) or with club security staff. As required of all National Institutes of Health funded grants, we obtained Institutional Review Board approval prior to the initiation of data collection.

Participants

At the conclusion of data collection, we had entrance information from a total of 2099 patrons. For these analyses, we included only patrons who arrived with someone else (approximately 90 % of patrons) and groups with both entrance and exit data (approximately 87 % of the sample). This resulted in a total of 615 groups with 1,642 individuals. The majority of the groups at the clubs were dyads (59.2 %) with the remainder in groups of three to eight. Most of the groups (70.4 %) had an average age less than 30 years, with 39.7 % having an average age less than 25 years. Nearly half of the groups were mixed gender (46.2 %), with approximately a quarter all female (27.8 %) and a quarter all male (26.0 %). A slight majority of the groups were composed of all heterosexuals (59.7 %) and approximately a fifth (18.7 %) was all LGBT. A small per cent of groups (20.3 %) represented all-student groups while 37.4 % of groups had no students.

Data collection

We used survey and biological samples collected at exit from the club to provide evidence of potential harm. Demographic and social context data were collected via entry and exit surveys. We chose multiple approaches to developing group aggregate scores: endorsement of the item by any group member, per cent of group members responding affirmatively, mean score of all responses, and discrepancy score (lowest response subtracted from highest response, higher scores indicating greater disagreement between group members).

Outcome measures

Alcohol Use Patron alcohol use was assessed with breath samples using a breathalyser (Intoxilizer 400PA™ CMI, Inc., Owensboro, KY) which provided an estimate of Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC). Two levels of alcohol consumption are defined as heavy use: impairment (BAC ≥ 0.05) and intoxication (≥ 0.08, the legal definition of intoxication for drink driving in California). If any group member had a BAC ≥ 0.05, the group received a score of 1 for impairment. If any group member had a BAC ≥ 0.08, the group score for intoxication was 1.

Impaired Driving

Participants who chose the option ‘Drive a car or motorcycle’ to the question ‘which of the following best describes how you plan to get home tonight’ were categorised as drivers. This item was then combined with the individual’s BAC. Individuals that indicated they were driving a car or motorcycle and had BAC ≥ 0.05 were considered to be impaired drivers. Groups were given a score of 0 for no drinking drivers and 1 if a drinking driver was present.

Drug use

We measured presence of drug use via saliva samples obtained with the Quantisal collection device (Immunalysis Corporation, Pomona, CA). We assessed the following substances: THC; cocaine; amphetamine/MDMA; opiates/analgesics; methadone; phencyclidine (PCP); and ketamine. If all members of the group tested negative for drugs at both entrance and exit the group was given a score of 0. The presence of any group member with a positive drug test at entry or exit gave the group a score of 1.

Aggression

Reported experiences of physical aggression and sexual aggression while in the club for the evening were analysed as separate outcomes. Physical aggression was defined as pushing or punching (‘Experienced being pushed or punched’) and sexual aggression was defined as unwanted touching or grabbing (‘Experienced being fondled or grabbed without invitation’). Response options were ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. If all members of a group responded ‘no’ to the question the group was given a score of 0. If any group member responded ‘yes’ to the question the group was given a score of 1.

Group Descriptors

Group size (sum)

The overall size of the group was calculated and considered both as a continuous (group size) and categorical (dyad vs 3+ group members) variable.

Demographics (mean, per cent, endorsement)

Demographics were assessed as follows: age, gender and sexual orientation, student status, employment status, educational attainment, and relationship status. The average age of the group was created as a continuous variable and also recoded into categories for mean age (≤25, >25 and ≤30, and >30). The remaining demographics were dichotomised for each respondent and then a sum taken of the responses within the social group. This sum score was then divided by the group size to get the per cent of any given characteristic, such as the per cent of women or the per cent of students or the per cent of individuals not in a relationship. We assessed gender and sexual orientation separately and together. Both full-time and part-time students were given the value ‘1’ and non-students ‘0’. Employment was ‘0’ for full-time and ‘1’ for part-time or unemployed. College graduation and higher was scored 1 while some high school through some college was scored 0. Surveys assessed relationship status with one question ‘How would you describe your current relationship status?’ from which two dichotomous variables were created: married/cohabiting and single (not dating). Finally, for a limited time, we asked if the respondent was currently in a relationship with someone else in the group. Groups where any respondent responded in the affirmative were considered a romantic group.

Group Context Measures

Special occasion (endorsement)

Respondents were asked a single question ‘are you at the club tonight to celebrate a special event?’ with responses of ‘no’ or ‘yes’. Any endorsement of this item gave the group a positive score. This item was not used for the entirety of data collection.

Group familiarity (mean)

We asked patrons what proportion of their social group members they had gone clubbing with prior as well as how many they know very well with responses to both on a scale from 0 ‘no one’ to 5 ‘everyone’.

Group safety (per cent and endorsement)

Three variables comprised safety assessments.

An individual’s concern about the group’s safety was assessed with the question ‘To what extent are you concerned about the group’s safety tonight?’ The response list had four options from ‘not concerned’ to ‘very concerned’. As responses formed a U-shaped curve with most responses falling into the end points of the scale, this variable was dummy coded so that ‘not concerned’ and ‘a little concerned’ were ‘0’ and ‘moderately concerned’ and ‘very concerned’ were ‘1’. A group mean was taken for this variable such that higher scores indicate greater per cent of members who were concerned.

Group safety issues were assessed using one question, ‘Does anyone in the group typically take responsibility for the safety of the group members?’ with responses ‘No one’ ‘One person’ ‘More than one person’ and ‘Don’t know’. Responses were dichotomised such that riskier answers were combined (no one and don’t know) as well as more protective responses (one or more people). If any member of the group identified at least one person in the group as the responsible party, the group response was coded as 1 or ‘yes’ for endorsement. If all members responded ‘no’ then the group was assigned 0.

Group drinking issues. Respondents were asked ‘Is there any member of the group who frequently gets drunk when s/he goes out? Responses were ‘no’ (0) and ‘yes’ (1). If any member of the group identified someone in the group as a person who frequently gets drunk, group history was coded as 1 or ‘yes’ for endorsement. If all members responded ‘no’ then the group was assigned 0.

Club safety (mean and discrepancy)

Participants were asked their assessment of the club as a safe space at both entry and exit. At entry they were asked ‘to what extent do you feel this club is a safe place to go tonight’ and at exit ‘did you feel this club was a safe place to go tonight’ each with responses of a 4-point Likert from 1 ‘not safe’ to 4 ‘very safe’.

Personal planned level of intoxication (mean and discrepancy)

Two variables comprised personal planned intoxication. Each participant’s expectation for their own drinking during the evening was assessed at entrance with the question, ‘How much do you plan to drink at the club tonight?’ Likert set of responses included: ‘sober’, ‘drink but not buzzed’, ‘a little buzzed’, ‘drunk’, and ‘very drunk’. Higher scores indicated increased levels of planned intoxication. A group mean was taken for this item. A second measure was created to reflect the discrepancy in scores within the group, by subtracting the lowest response in the group from the highest response in the group. A high discrepancy score meant that one group member expected to stay more sober while another member intended to drink to a much higher level of intoxication.

Assessment of other group members’ planned level of substance use (mean and discrepancy)

Four variables comprised perceived group substance use. Each participant’s expectation for their group’s drinking was assessed at entrance with the question, ‘Tonight, do you expect that most of the members of your group will…?’ Likert responses were the same as personal planned level. Higher scores indicated greater levels of intoxication anticipated within the group. A group mean was taken for this item. A discrepancy score was also created, similar to the personal variable. A high discrepancy score for the planned level of intoxication for the group indicated that there was a greater discrepancy about the overall expectation for group behaviour for the evening: one member expected the group to stay more sober while another member of the group expected that they would drink to a higher level of intoxication collectively. We also asked with regard to drug use (‘What type of drug use do you expect in this group tonight?’) and the same procedures were followed to create a group mean and a discrepancy score.

Analysing the data

We used Latent Class Analysis as a statistical procedure for its ability to identify subgroups within a population. This allowed us to identify groups who had the same sets of experiences and then look at what might be common among the groups aside from having the same set of experiences. Using Mplus v.7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2014) we employed Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to determine patterns of risk on six dichotomous experiences within a social drinking group:

having a driver impaired by alcohol

having at least one impaired group member

having at least one intoxicated group member

having a group member who tested positive for drug use

having a group member who had experienced physical aggression

having a group member who had experienced sexual aggression.

We estimated models ranging from one to six classes to ensure that at least one class contained more than one experience. Consistent with Latent Class Analysis procedure for interpretation, we relied on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values, where lower values reflect more optimal balance between model fit and parsimony. A four-class solution was deemed the best fit using only these criteria. However, that particular solution did not identify a class that was low for all indicators, rather indicating four classes that had at least one identified behaviour/experience and none indicating groups for whom participating in nightlife culture might be sufficient risk (drug use and/or low levels of alcohol consumption may not be inherently risky in a nightclub context). Although there are many concerning experiences one can have in nightclubs, there is no evidence that clubs are risky to all patrons or all social groups. Given our interest in determining how risk experiences co-occur in various ways, we wanted consider social groups that may not experience any risk whatsoever. We therefore reviewed the models with five- and six-class solutions. The six-class solution greatly increased the Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion values. We considered the five-class solution then, as it met the need for parsimony (did not excessively increase Akaike Information Criterion or Bayesian Information Criterion values) and yet identified one class of social groups that had little in the way of problem behaviour/experiences during the evening in the club. We then examined specific patterns of risk as well as differences between the five classes in demographics, group characteristics, and indications of social context for that evening’s behaviour using analyses of variance (for mean values of continuous variables) and Chi-square tests (for per cent of categorical responses).

Limitations

There are several caveats in considering our results. These findings are specific to club settings that offer large events. Further research is needed to determine if similar risk groups emerge in other drinking establishments or other club events. Our data collection methods required the consent and cooperation of the clubs. Clubs can attract patrons with specific characteristics, thus findings may not generalise to all clubs. Although collecting data onsite as patrons entered and exited the clubs maximised temporal proximity, the consumption of alcohol both before and during the event by the majority of participants potentially impacted the accuracy of the participants’ recall for those questions that were self-report (such as aggression experiences). Finally, intercepting club patrons as they enter and exit the club limited the number of questions that could be asked.

Findings

Our analyses indicated that groups have five distinct sets of experiences within an evening. These sets of experiences (classes) varied in terms of constellation of risk as well as many group characteristics. A summary of the five constellations of risk based on six experiences (BAC ≥.05, BAC ≥ .08, drinking driver, drug use, sexual aggression, physical aggression) are detailed in Table 1. We named the classes based upon the most prominent risk experiences. A more detailed presentation of group compositions is provided in Table 2 and social context in Table 3.

Table 1.

Group Risk Classes (N=615)

| Class | Limited Vulnerabilitya |

Aggression Vulnerabilityb |

Substance Usersc |

Impaired Driversd |

Multi- Issuee |

χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 207 | 103 | 238 | 12 | 55 | |

| % | 33.7 | 16.7 | 38.7 | 2.0 | 8.9 | |

| Impaired driver | 0.0c,d,e | 0.0c,d,e | 7.1a,b,d | 58.3a,b,c,e | 9.1 a,b,d | 97.6** |

| BAC > .05 | 35.7 c,d,e | 27.2 c,d,e | 100.0a,b | 100.0 a,b | 100.0 a,b | 311.5** |

| BAC > .08 | 0.0c,e | 0.0c,e | 100.0a,b,d,e | 0.0 c,e | 98.2a,b,c,d | 611.1** |

| Sexual aggression experience | 0.0b,c,d,e | 100.0a,c,d | 21.7a,b,d,e | 66.7a,b,c,e | 100.0 a,c,d | 425.0** |

| Physical aggression experience | 21.7b,e | 68.9a,c,d,e | 19.3 b,e | 0.0 b,e | 100.0 a,b,c,d | 201.7** |

| Used drugs | 31.7c,d,e | 30.1c,d,e | 42.4a,b,d | 91.7a,b,c,e | 52.7a,b,d | 27.6** |

p < .05

p < .01

Superscript letters indicate classes significantly different from each other via post hoc analyses

Table 2.

Group Demographic Context by Class (N=615)

| Class | Limited Vulnerbilitya |

Aggression Vulnerabilityb |

Substance Usersc |

Impaired Driversd |

Multi- Issuee |

χ2 / F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||||

| Group size (M) | 2.4b,c,e | 2.7a,e | 2.8a,e | 2.8e | 3.5a,b,c,d | 14.7** |

| Dyad (%) | 75.8b,c,e | 56.3a,e | 52.1a,e | 66.7e | 30.9a,b,c,d | 47.6** |

| Age (M) | 29.7b,c,e | 23.9a,c | 28.4a,b,e | 26.6 | 24.8a,c | 16.9** |

| Age 25 and under (%) | 30.9 | 62.1 | 32.4 | 33.3 | 63.6 | 59.9** |

| Age 30 and over (%) | 41.5b,e | 12.6 a,c | 29.8b,e | 25.0 | 16.4a,c | |

| Percent males (M) | 54.9b | 34.5a,c | 50.8b | 52.8 | 46.0 | 5.5** |

| All-male groups | 30.4 | 19.4 | 25.2 | 25.0 | 25.5 | 4.5 |

| All female groups | 21.7b | 49.5a,c,d,e | 24.4b | 16.7b | 27.3b | 30.1** |

| Percent gay/lesbian (M) | 24.8 | 23.8 | 32.6 | 40.3 | 33.8 | 1.9 |

| Percent straight women (M) | 34.4b | 52.5a,c,e | 31.3b | 34.7 | 40.8b | 6.9** |

| Percent straight men (M) | 40.3b,e | 23.7a,c | 34.9b | 25.0 | 25.3a | 4.6** |

| Percent lesbian (M) | 10.0 | 13.0 | 16.2 | 12.5 | 12.3 | 1.5 |

| Percent gay men (M) | 14.5 | 10.7 | 15.8 | 27.8 | 20.7 | 1.5 |

| Percent married/cohabiting (M) | 25.6b | 12.1a,c | 23.0b | 13.9 | 16.2 | 3.5** |

| Percent single no relationship (M) | 28.8b | 41.7a,c | 32.3b | 38.3 | 35.8 | 2.78* |

| Percent part-time (or un-) employed (M) | 39.1b,e | 58.5a,c,d | 41.0b,e | 35.8b,e | 59.3a,c,d | 8.5** |

| Percent college degree (M) | 57.5b,e | 32.6a,c | 60.7b,e | 47.2 | 39.0a,c | 12.3** |

| Percent student (M) | 34.9b,e | 59.0a,c | 34.6b,e | 48.6 | 48.7a,c | 10.0** |

| Relationship context (n=272) | ||||||

| Any romantic between group members (%) | 27.5b,d,e | 8.7a,c | 27.3 b,d,e | 0.0 a,c | 14.5 a,c | 22.7** |

| Romantic dyads | 36.7b,c,d,e | 7.7a | 25.2a | 0.0a | 18.8a | 11.4* |

| Romantic among members (3+ group) | 15.6 | 26.9 | 29.4 | 0.0 | 31.2 | 7.4 |

p < .05

p < .01

Superscript letters indicate classes significantly different from each other via post hoc analyses

Table 3.

Group Social Context by Class (N=615)

| Class | Limited Vulnerabilitya | Aggression Vulnerabilityb | Substance Usersc | Impaired Driversd | Multi-Issuee | χ2 / F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Special Occasion | ||||||

| Overall yes | 30.9c,e | 39.8 | 45.0a,d | 25.0c,e | 54.5a,d | 15.5** |

| Comparison by gender (n=245) | ||||||

| % all female groups | 29.7 | 46.3 | 25.2 | 33.3 | 23.3 | 8.7 |

| % all male groups | 25.0 | 19.5 | 23.4 | 0.0 | 30.0 | |

| % mixed gender groups | 45.3 | 34.1 | 51.4 | 66.7 | 46.7 | |

| Group knowledge | ||||||

| Average report | 3.72b,c,e | 4.06a | 3.91a | 3.93 | 4.07a | 2.85* |

| Group prior clubbing | ||||||

| Average report | 3.72b,c,e | 4.09a | 3.93a | 3.93a | 4.07a | 3.30* |

| Assessment of Safety | ||||||

| Entry | ||||||

| Lowest report | 3.11b,e | 2.91a,c | 3.11b,e | 3.25e | 2.73a,c,d | 5.90** |

| Discrepancy | 0.58b,e | 0.79a,e | 0.68e | 0.58e | 1.11a,b,c,d | 7.89** |

| Exit | ||||||

| Average report | 3.64b,c,e | 3.45a,c,d | 3.75a,b,e | 3.72b,e | 3.46a,c,d | 12.18** |

| Lowest report | 3.35b,e | 3.11a,c | 3.45b,e | 3.50e | 2.93a,c,d | 9.43** |

| Highest report | 3.89b | 3.79a,c,d | 3.95b | 4.00b | 3.89 | 4.59** |

| Discrepancy | 0.54e | 0.68c,e | 0.50b,e | 0.50e | 0.96a,b,c,d | 6.51** |

| Same Night Characteristics | ||||||

| Responsible person (% no) | 10.6 | 5.8 | 12.2 | 16.7 | 7.3 | 4.3 |

| Regularly drunk person (% yes) | 59.5 | 62.0 | 88.6 | 83.3 | 87.3 | 61.7** |

| Percent concerned (M) | 42.2b,e | 51.3a | 44.6e | 35.3e | 58.0a,c,d | 3.2* |

| Expectation for group drinking (M) | 1.6b,c,e | 1.4a,c,e | 2.2a,b | 1.9 | 2.0a,b | 20.2** |

| Expectation discrepancy group drinking (M) | 0.8e | 0.8e | 0.9e | 0.8e | 1.3a,b,c,d, | 5.7** |

| Expectation for group drugging (M) | 0.2c,e | 0.2e | 0.3a | 0.5 | 0.4a,b | 3.1* |

| Expectation discrepancy group drugging (M) | 0.2c,e | 0.3 | 0.3a | 0.2 | 0.4a | 3.8** |

| Expectation for self drinking (M) | 1.2b,c,d,e | 0.9a,c,d,e | 2.0a,b,e | 1.8a,b | 1.7a,b,c | 43.6** |

| Expectation discrepancy self drinking (M) | 1.0e | 1.0e | 1.1e | 1.2 | 1.5a,b,c | 3.2** |

p < .01

p < .05

Superscript letters indicate classes significantly different from each other via post hoc analyses

Class 1: Limited Vulnerability (n = 207 social groups, 33.7 %)

Outcomes

The social groups in this class are characterised by their general low experience for all the risks considered in these analyses. None had intoxicated members, impaired drivers, or experienced any sexual aggression. The majority had no members who were impaired and most had no members who had used drugs that evening.

Group Descriptors

The social groups in this class were predominantly dyads, older individuals, and a slightly greater proportion of men. This class stands out for the romantic relationship status of group members. More than a third were romantically involved couples and these groups had the highest average per cent of married/cohabiting individuals.

Group Context

Relative to the other classes, few groups were celebrating a special occasion. Despite the presence of dating couples in this group, they reported the lowest per cent of group members they know well and with whom they had previously been at a club. These social groups had amongst the lowest assessments of group risk behaviour: low per cents of those who reported someone who frequently gets drunk and expectations for group drinking, group drug use, and personal drinking. In addition, there was little discrepancy in the safety assessments. These groups seem geared to an uneventful evening at the club, with lower and more similar expectations for alcohol and drug use, suggesting a shared understanding among group members.

Class 2: Aggression Only (n = 103 social groups, 16.7 %)

Outcomes

Within this class, all social groups had at least one member who experienced sexual aggression. Also, more than two thirds of the groups had at least one member who experienced physical aggression. The risk was limited to aggression however, as there were no drinking drivers, most groups did not have members who were impaired and no groups in this class had any members who were intoxicated.

Group Descriptors

A distinctive demographic profile was noted within this class, with half all-female groups and the highest average per cent of students. This class had the youngest average mean age and most were under 25 years. On average, many of the groups were dyads with very few reporting romantic partners amongst the group members.

Group Context

The social groups in this class had the lowest assessments of group risk behaviour: second lowest per cent who reported a group member who frequently gets drunk and lowest self-report drinking expectation and expectations for group drinking and group drug use. In addition, the Aggression Only class had indicators of caution, with the lowest assessments of safety at both entry and exit and the most groups where someone identified a responsible group member. They had among the highest reports of the per cent of group members they knew well and had been to a club with previously. These groups were similar in their shared expectation for generally low alcohol and drug use, but were more familiar with each other, were more likely to have been to clubs together, and had more concern about safety.

Class 3: Substance Users (n = 238 social groups, 38.7 %)

Outcomes

Social groups in this class are characterised by alcohol use, impaired drivers, and drug use during the evening but little aggression experience. All of the groups had at least one person who was impaired and all had a member who was intoxicated. These groups had a high average BAC at entry (.07) and exit (.09). In the Substance User class, there were some impaired drivers, though the per cent was low.

Group Descriptors

The social groups in this class tended to be older (average age just under 30), most were evenly split in terms of gender, half of the groups were dyads and almost a third had a romantic relationship between group members. Many of the groups had members with a college degree and few groups were comprised of students.

Group Context

The groups in this class had some of the highest assessments of group risk behaviour: highest per cent of those who reported a group member who frequently gets drunk and expectations for group drinking and self-report drinking. This was also a class where groups reported the highest feelings of safety at exit from the club and almost half were at the club for a special occasion. There generally seem to be a shared understanding for risk perception: high safety assessments, low concern, and high expectation for indulging in substance use.

Class 4: Impaired Drivers (n = 12 social groups, 2.0 %)

Outcomes

By far the smallest class of social groups, this class was characterised by drug use, alcohol use and a high per cent of social groups who had a driver with BAC > .05. This class was distinct from Substance Users in the focus on impaired driving. All of the groups in this class had at least one member who was impaired though none had a member who was intoxicated (by extension, none of the drinking drivers were legally intoxicated either). This is tempered by the additional result that almost all groups had at least one member who tested positive for drugs (91.7 %) which may indicate a number of drugged drivers as well.

Group Descriptors

The size of the groups in this class tended to be midrange; two-thirds of the groups were dyads and unlike any of the other classes, none of the groups had a romantic relationship amongst their members. They are also younger than the Substance Users with approximately three-quarters of the groups having an average age under 30. Groups tended to be about half students, half college graduates, half men, and groups averaged about 40 % single (not dating) and 40 % gay or lesbian.

Group Context

The Impaired Driver class is remarkable in its groups having the highest expectation for group drug use and high expectations for personal drinking. They also had high assessments of safety at both entry and exit. Similar to the Substance Users, there is a co-occurrence between perceived safety and increased risk behaviour.

Class 5: Multi-Issue (n = 55 social groups, 8.9 %)

Outcomes

This class was characterised by groups that had multiple risk experiences during that evening. All groups in this class had at least one member who was impaired and almost all had at least one who was legally intoxicated. Follow-up analyses on the social groups’ average BAC indicated that the mean of all group BAC averages (the mean of the mean for all groups in this class) exiting the club was the legal driving limit of .08. The Multi-Issue class is remarkable in that all groups had a member who had experienced sexual aggression that evening and all had a member who experienced physical aggression. More than half of the groups had a member who tested positive for drugs.

Group Descriptors

This class had the largest groups and only a third was comprised of dyads. This class tended to have younger groups, with an average mean age of 24.8. The average gender composition was half male/half female. Very few of the groups contained members with a romantic connection to each other, few had a college degree (about half of most groups were students) and the groups tended to be composed of individuals who were unemployed or employed part-time.

Group Context

Most of the groups had someone who reported having a frequently drunk member. This group had the lowest assessments of safety both for entry and exit and the greatest discrepancy scores indicating that, in light of the low average, one member of the group feels quite unsafe while another person is more in the centre. These groups also reported the highest familiarity with group members, knowing most of them well and having attending clubs with them before. More than half of groups asked were celebrating special occasion (many of whom were single-gender groups). The hallmark of the groups in this class is the lack of shared vision for the evening. The groups had the largest discrepancy scores with regard to expectations for behaviour (themselves and group members) and the perception of safety, indicating disparate ideas for what the night in the club would entail.

Discussion

In this article we have increased knowledge of young adults’ experience in nightclubs by considering the social context, specifically the social drinking group, and its relationship to risk.

Patterns of Experiences

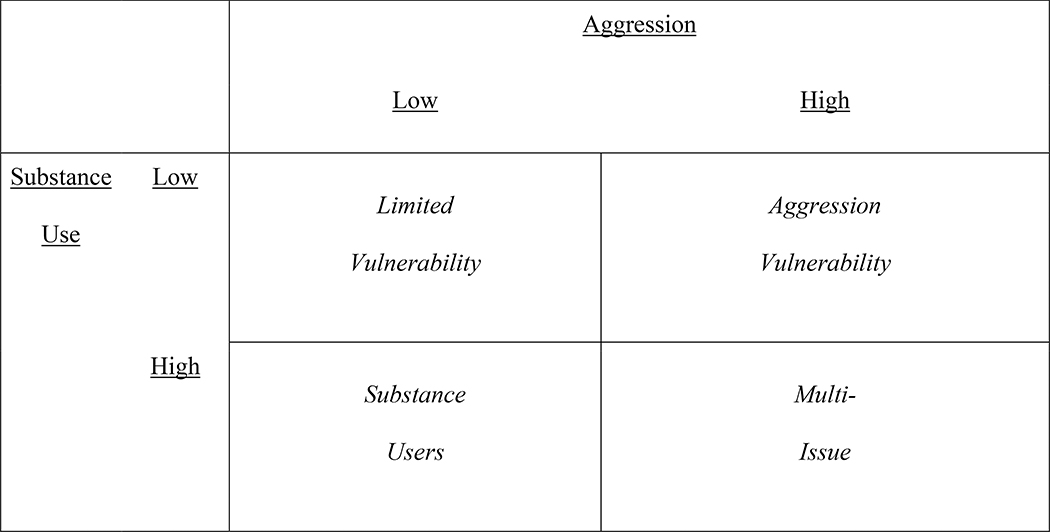

We found that there were distinctive patterns of risk experiences. The various risk events which we have focussed on in this article are all frequent events in nightclubs. However, there are differences between them; while drug, alcohol, and impaired driving are all risks resulting from the action of a patron, physical and sexual aggression are the result of the actions of other patrons. Both types of risk expose a patron to physical harm, but they have very different in their dynamics: experiences of substance misuse need to be considered separately from those of aggression. While researchers have linked aggression to alcohol (Cherpitel, Ye, Bond, Room, & Borges, 2012; Graham & Homel, 2008; Graham et al., 2006; Harford et al., 2003; Krienert & Vandiver, 2009; Leonard, Quigley, & Collins, 2002), the presence of two groups with high rates of aggression yet vastly different alcohol use indicates that limiting alcohol use will not necessarily act as a protective strategy for all social groups. It is possible to conceptualise our findings as a matrix: with one axis aggression (high or low) and the other substance use (high or low). The Limited Vulnerability was low on both, Aggression Vulnerability was low on substance use but high on aggression, Substance Users high on use but low on aggression, and Multi-Issue was high on both (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Matrix of Risk Experience Classes

The Impaired Driver class doesn’t fit within this matrix. Given successful media campaigns in the U.S. about drinking and driving, it is no surprise that this class was the smallest and, it is important to note, the drivers in these groups kept their alcohol use relatively low. None of the drivers would be considered legally intoxicated in 49 states. However, this class had the highest number of groups with a drug-using member. This class of experiences is worth investigating further, as the groups in this class put the greater public at risk by driving and are likely different than the other groups in ways potentially not captured with such a small sample size.

Patterns in Group Composition

We found that the composition and characteristics of a social group influenced the pattern of experiences that the group experienced. The groups with limited vulnerability or risk behaviour tended to have an older average age. Romantic relationships between group members seemed to be one important distinguishing factor for low vulnerability to aggression. Of note is the lack of romantic relationships among members of groups that had impaired driver, something that might emphasise the protective nature of those relationships. It could be that those who club with their romantic partners have more interest in making sure that the partner is safe. It could also mean that the overall tenor of the evening is qualitatively different when a partner is present, even if the couple is among a larger group.

Patterns in Group Context

We found that group patterns and expectations are different between those having the different constellations of experiences. Familiarity seemed a factor for groups that proved vulnerable to aggression. Those who reported the highest assessments of group familiarity and prior clubbing experience were the ones who had the most groups experiencing aggression. This is consistent with other findings that familiarity can result in lax vigilance.

It is interesting to consider the factors which make groups vulnerable to either substance use or aggression. Groups in the Multi-Issue class were more likely to be celebrating a special occasion and have higher expectations for drinking. Indeed, it is not uncommon to expect greater than usual levels of drinking when out for a special event, such as a birthday or stag/hen party. What distinguished the multi-issue evenings from those that involved only substance use were the discrepancies among group members. There seemed to be little shared vision for how the evening would unfold. By contrast, those groups who had evenings characterised predominantly by substance use with little aggression had more consistency of expectations for the evening’s activities.

Defining Safety

While clubs can be perceived as safe places for substance use, the assessments of safety and familiarity were important and distinct. All classes saw average increases in club safety assessments from entrance to exit, indicating that most generally felt the club was a safer space at the end of the evening. It would be interesting to know then, what the criteria are for a patron to feel safe in a club, as the increase indicates that the assessment is not based on prior attendance at that particular club and seems unrelated to experiences during the evening.

It is possible that a lower assessment of safety of the club is balanced out by a higher sense of safety with group members, thus shifting the criteria for the assessment of subjective risk. It was those who experienced aggression who had the highest familiarity scores, the lowest club safety assessments at entry, and the highest per cent of groups with concern about their safety. Yet the groups in one class proceeded to consume a substantial amount of alcohol while the groups in the other did not. The distinguishing characteristic was that there was a greater average discrepancy among group members. The discrepancy scores of the Multi-Issue class were consistently highest and significantly so. These may be groups where individuals know some members of the group enough to feel familiar but not well enough to have a clear shared expectation for the evening’s behaviour. It can be assumed that special occasions (such as stag nights or celebration of legal drinking age attainment) would include heavy drinking. However, the combination of high discrepancy scores as well as low mean expectation scores, with the mean score a response of getting ‘a little buzzed’, indicate that higher alcohol use is not assumed.

It was the impaired driving constellation that had the highest assessments of club safety at the beginning and end of the evening and the fewest individuals concerned about safety for the evening. Indeed, they kept their alcohol consumption generally low for the evening, but had very high rates of drug use which could put themselves and others at risk for vehicular accidents.

Societal Risk

The premise of our work is that assessment of personal subjective risk is not sufficient for approaches to harm reduction. The assessment of clubs as safe places in which to participate in drug and alcohol use has implications for the others in the social group, exposing them to potential aggression, ejection from the club, or shifting their focus from pleasure-seeking to care-taking. Our study has implications for those interested in reducing the risk of physical harm to nightclub patrons and those in the surrounding community. Differences in group context can provide entrée to risk-reduction strategies. The assessment of familiarity and safety of the context, as well as expectations for the evening’s behaviour, have implications for intervention to minimise vulnerability to harm. Discrepancies can be subject to discussion and modification, and familiarity could give leverage to the desire to minimise harm to friends and romantic partners. Rather than seek to minimise harm through awareness, the development of shared vision and expectation for the evening in the club seems to hold promise as a risk reduction strategy. This would have the incentive of increasing the potential for pleasure-seeking, often a reason for attending the clubs at the outset.

Conclusion

Our research highlights the impact of the social group on both safety assessment and potential risks experienced by nightclub patrons. Different classes of groups were identified that resulted in increased or decreased risks from aggression and overuse of alcohol/drugs, highlighting the ways in which they may co-occur. In our work, risk is conceptualised as not merely an individual level phenomenon but as related to the immediate social group in which the individual is embedded. Further, the perception of safety within the social group may play an important role in individuals making more risky choices during their evening and this needs deeper investigation. Clearly, safety and subjective risk assessment within the social setting of nightclubs is an interactional, complex phenomena.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grants Number 1 RC1-AA019110–01 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and Number 5 R01-DA018770–04 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Drug Abuse, or National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anderson TL, Kavanaugh PR, Rapp L, & Daly K (2009). Variations in clubbers' substance use by individual and scene-level factors. Adicciones, 21(4), 289–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Hughes K, Calafat A, Juan M, Ramon A, Rodriguez JA, . . . Phillips-Howard P (2008). Sexual uses of alcohol and drugs and the associated health risks: a cross sectional study of young people in nine European cities. BMC Public Health, 8, 155–155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DJ (2002). An ethnographic study of sources of conflict between young men in the context of the night out. Psychology, Evolution & Gender, 4, 3–30. doi: 10.1080/1461666021000013742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau B, Miller BA, Johnson MB, & Voas RB (2015). Method of transportation and drinking among club patrons. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 32, 11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.trf.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes HF, Miller BA, Johnson MB, & Voas RB (2014). Indicators of Club Management Practices and Biological Measurements of Patrons’ Drug and Alcohol Use. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(14), 1878–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Room R, & Borges G (2012). Attribution of alcohol to violence-related injury: self and other's drinking in the event. Journal of Studies On Alcohol and Drugs, 73(2), 277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD (2010). Review of 'Raising the bar: Preventing aggression in and around bars, pubs and clubs'. Addiction, 105(1). doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02868_2.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum J, O'Grady M, Armeli S, & Tennen H (2012a). Change and Stability in Active and Passive Social Influence Dynamics during Natural Drinking Events: A Longitudinal Measurement-Burst Study. Journal Of Social And Clinical Psychology, 31(1), 51–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullum J, O'Grady M, Armeli S, & Tennen H (2012b). The Role of Context-Specific Norms and Group Size in Alcohol Consumption and Compliance Drinking During Natural Drinking Events. Basic & Applied Social Psychology, 34(4), 304–312. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.693341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR (2002). Alcohol-related aggression during the college years: Theories, risk factors, and policy implications. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, SUPPL14, 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, & Homel R (2008). Raising the Bar: Preventing Aggression in and Around Bars, Pubs and Clubs. Devon, UK: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Osgood WD, Wells S, & Stockwell T (2006). To What Extent is Intoxication Associated with Aggression in Bars? A Multilevel Analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Wells S, Bernards S, & Dennison S (2010). "Yes, I do but not with you": Qualitative analyses of sexual/romantic overture-related aggression in bars and clubs. Contemporary Drug Problems, 37, 197–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, & Plant MA (2007). Bad bars: A review of risk factors. Journal of Substance Use, 12(3), 157–189. doi: 10.1080/14659890701374703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ (2007). The spatial ecology of alcohol problems: Niche theory and assortative drinking. Addiction, 102, 870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Wechsler H, & Muthen BO (2003). Alcohol-related aggression and drinking at off-campus parties and bars: A national study of current drinkers in college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homel R, Carvolth R, Hauritz M, McIlwain G, & Teague R (2004). Making licensed venues safer for patrons: what environmental factors should be the focus of interventions? Drug and Alcohol Review, 23(1), 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Voas R, Miller B, Bourdeau B, & Byrnes H (2015). Clubbing with familiar social groups: Relaxed vigilance and implications for risk. Journal of Studies On Alcohol and Drugs, 76(6), 924–927. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Voas R, & Miller BA (2012). Driving decisions when leaving electronic music dance events: Driver, passenger, and group effects. Traffic Injury Prevention. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MB, Voas RA, Miller BA, & Holder HD (2009). Predicting drug use at electronic music dance events: Self-reports and biological measurement. Evaluation Review, 33(3), 211–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ker K, & Chinnock P (2008). Interventions in the alcohol server setting for preventing injuries. The Cochrane Database Of Systematic Reviews(3), CD005244. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005244.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krienert J, & Vandiver D (2009). Assaultive behavior in bars: A gendered comparison. Violence and Victims, 24, 232–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange JE, Johnson MB, & Reed MB (2006). Drivers within Natural Drinking Groups: An Exploration of Role Selection, Motivation, and Group Influence on Driver Sobriety. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse, 32(2), 261–274. doi: 10.1080/00952990500479597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, & Geisner IM (2004). Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors: Journal Of The Society Of Psychologists In Addictive Behaviors, 18, 203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BN, & Collins LR (2002). Physical aggression in the lives of young addults: Prevalence, location, and severity among college and community samples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17(5), 533–550. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S, & Homel R (1997). Danger on the dance floor: a study of interior design, crowding and aggression in nightclubs In Homel R (Ed.), Policing for prevention: reducing crime, public intoxication and injury (Vol. 7, pp. 91–113). Monsey, New York: Criminal Justice Press. [Google Scholar]

- McClatchley K, Shorter GW, & Chalmers J (2014). Deconstructing alcohol use on a night out in England: Promotions, preloading and consumption. Drug and Alcohol Review, 33(4), 367–375. doi: 10.1111/dar.12150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Bourdeau B, Johnson MB, & Voas RB (2015). Experiencing aggression in clubs: Social group and individual level predictors. Prevention Science, 16, 527–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Byrnes HF, Branner A, Johnson M, & Voas R (2013). Group influences on individuals' drinking and other drug use at clubs. Journal of Studies On Alcohol and Drugs, 74(2), 280–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Byrnes HF, Branner AC, Voas R, & Johnson MB (2013). Assessment of club patrons' alcohol and drug use: the use of biological markers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(5), 637–643. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Furr-Holden D, Johnson M, Holder H, Voas R, & Keagy C (2009). Biological Markers of Drug Use in the Club Setting. Journal of Studies On Alcohol and Drugs, 70(2), 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2014). Mplus Users Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lindgren KP, Knee CR, Fossos N, & DiBello A (2011). The influence of confidence on associations among personal attitudes, perceived injunctive norms, and alcohol consumption. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors: Journal Of The Society Of Psychologists In Addictive Behaviors, 25(4), 714–720. doi: 10.1037/a0025572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Permuth-Wey J, & Borenstein AR (2009). Financial remuneration for clinical and behavioral research participation: ethical and practical considerations. Annals of Epidemiology, 19, 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Grov C, Delucchi K, Kelly BC, & Parsons JT (2010). Typology of club drug use among young adults recruited using time-space sampling. Drug Alcohol Depend, 107(2–3), 119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JC (2009). Bouncers and barroom aggression: A review of the research. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 14(1), 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Dimoff JD, Levine JM, Moreland RL, & Votruba-Drzal E (2012). The effects of alcohol and dosage-set on risk-seeking behavior in groups and individuals. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors: Journal Of The Society Of Psychologists In Addictive Behaviors, 26(2), 194–200. doi: 10.1037/a0023903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Kearns-Bodkin J, & Livingston J (2009). Effect of precollege drinking intentions on womens college drinking as mediated via peer social influences Journal of Studies On Alcohol and Drugs, 70, 575–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomczyk S, Isensee B, & Hanewinkel R (2015). Latent classes of polysubstance use among adolescents—a systematic review. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimpop RM (1994). The psychology of risk-taking behavior. Amsterdam: North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Furr-Holden D, Lauer E, Bright K, Johnson MB, & Miller B (2006). Portal surveys of time-out drinking locations: a tool for studying binge drinking and AOD use. Evaluation Review, 30(1), 44–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas RB, Johnson MB, & Miller BA (2013). Alcohol and drug use among young adults driving to a drinking location. Drug And Alcohol Dependence, 132(0), 69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Dumas TM, Bernards S, Kuntsche E, Labhart F, & Graham K (2015). Predrinking, alcohol use, and breath alcohol concentration: A study of young adult bargoers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 683–689. doi: 10.1037/adb0000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Graham K, & Tremblay PF (2009). “Every Male in There Is Your Competition”: Young Men's Perceptions Regarding the Role of the Drinking Setting in Male-to-Male Barroom Aggression. Substance Use & Misuse, 44(9/10), 1434–1462. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Neighbors C, Tremblay PF, & Graham K (2011). Defending girlfriends, buddies and oneself: Injunctive norms and male barroom aggression. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 416–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedermann W, Niggli J, & Frick U (2014). The Lemming-effect: Harm perception of psychotropic substances among music festival visitors. Health, Risk & Society, 16, 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn JO (2015). Towards a better understanding of risk-taking: Key concepts, dimensions and perspectives. Health Risk & Society, 17, 99–114. [Google Scholar]