Abstract

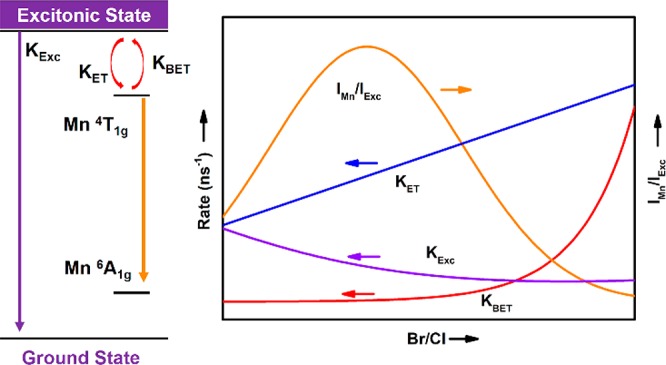

Doping nanocrystals (NCs) with luminescent activators provides additional color tunability for these highly efficient luminescent materials. In CsPbCl3 perovskite NCs the exciton-to-activator energy transfer (ET) has been observed to be less efficient than in II–VI semiconductor NCs. Here we investigate the evolution of the exciton-to-Mn2+ ET efficiency as a function of composition (Br/Cl ratio) and temperature in CsPbCl3–xBrx:Mn2+ NCs. The results show a strong dependence of the transfer efficiency on Br– content. An initial fast increase in the relative Mn2+ emission intensity with increasing Br– content is followed by a decrease for higher Br– contents. The results are explained by a reduced exciton decay rate and faster exciton-to-Mn2+ ET upon Br– substitution. Further addition of Br– and narrowing of the host bandgap make back-transfer from Mn2+ to the CsPbCl3–xBrx host possible and lead to a reduction in Mn2+ emission. Temperature-dependent measurements provide support for the role of back-transfer as the highest Mn2+-to-exciton emission intensity ratio is reached at higher Br– content at 4.2 K where thermally activated back-transfer is suppressed. With the present results it is possible to pinpoint the position of the Mn2+ excited state relative to the CsPbCl3–xBrx host band states and predict the temperature- and composition-dependent optical properties of Mn2+-doped halide perovskite NCs.

Introduction

Lead halide perovskite NCs CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) emerge as a promising class of materials for optoelectronic application because of their superb optical properties, e.g., high photoluminescence quantum yield (PL QY), short exciton lifetime, wide spectral tuning range covering the full visible spectrum, and ease of preparation.1−6 Incorporation of luminescent dopants (Mn2+, lanthanides ions) has been reported recently and provides additional flexibility in tuning the optical properties for specific applications.7−12 Of the particular interest is the dopant ion Mn2+, whose efficient broad band emission is centered around ∼600 nm and is detuned from the absorption of the perovskite host, thus preventing reabsorption of the exciton emission which is important in e.g. solar cell applications. Recently, Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs assisted solar cell have been successfully manufactured.13,14

Despite the extensive research,15−17 the understanding of energy transfer between exciton and Mn2+ is still limited, especially the combined role of halide composition (Br/Cl ratio), Mn2+ content, and temperature. Energy transfer (ET) from the exciton to Mn2+ is orders of magnitude slower than in Mn2+-doped II–VI QDS (CdS/ZnS:Mn2+), and even for high Mn2+ doping concentrations exciton emission from the perovskite host is still present.9,15,16,18 The inefficient ET has been attributed to the more ionic character of the perovskite NCs and the weaker confinement which reduces ET by wave function overlap. The influence of Cl– ↔ Br– substitution on the ET is not extensively studied. In various reports, a decrease in the relative Mn2+ emission intensity was observed upon replacing Cl– by Br–.7,19 The decrease can be explained by a narrowing of the bandgap which allows for back-transfer from Mn2+ to the exciton state for higher Br– content.7,19 Upon close inspection, however, an initial increase in relative Mn2+ emission intensity is observed for low Br– content, followed by a rapid decrease of the Mn2+/exciton emission intensity ratio (IMn/IExc). Here we aim to gain further understanding of the exciton-to-Mn2+ ET in mixed CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs and focus on systems with a relatively low Br– content. Temperature (4.2–295 K)-dependent emission of a series of Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3–xBrx (x: 0–1.18) NCs is reported. Upon anion exchange of Cl– by Br– we find two distinct regimes. In the first regime, where the exciton peak shifts from 405 to 420 nm, there is a strong increase in the Mn2+ to exciton emission intensity ratio with increasing Br– content. The increase is explained by a reduced exciton decay rate combined with faster exciton-to-Mn2+ ET. In the second regime, further replacement of Cl– by Br– leads to a continued exciton red-shift from 420 to 440 nm but now accompanied by a marked decrease of the Mn2+/exciton intensity ratio. This decrease is explained by back-transfer from Mn2+ to exciton state because of narrowing of the bandgap resulting in overlap of Mn2+ excited states with host band states. In addition, the temperature dependence and decay kinetics of both exciton and Mn2+ emission have been measured and reveal a weaker temperature dependence of the exciton-to-Mn2+ ET efficiency than previously reported for pure CsPbCl3:Mn2+ NCs.16 The present results provide important insight into the ET transfer dynamics of Mn2+-doped perovskite nanocrystals that will aid to optimize the ET and Mn2+ luminescence efficiency.

Results and Discussion

Fast anion-exchange is one of the unique properties of lead halide perovskite nanocrystals (NCs).20,21 The rapid exchange allows a facile postsynthetic treatment to continuously vary the composition and properties of these materials. Replacement of lighter halides (Cl–) by heavier halide ions (Br– or I–) decreases the bandgap, or vice versa. Notably, during such rapid anion exchange the cationic sublattice of NCs is largely unaffected because of the lower mobility of the cations. As a result, the parent NCs’ morphological features and size dispersity are maintained during the anion-exchange process.

Anion exchange can be achieved by addition of a halide precursor. As a control experiment, the influence of Cl– ↔ Br– anion exchange was first investigated for undoped CsPbCl3 NCs.

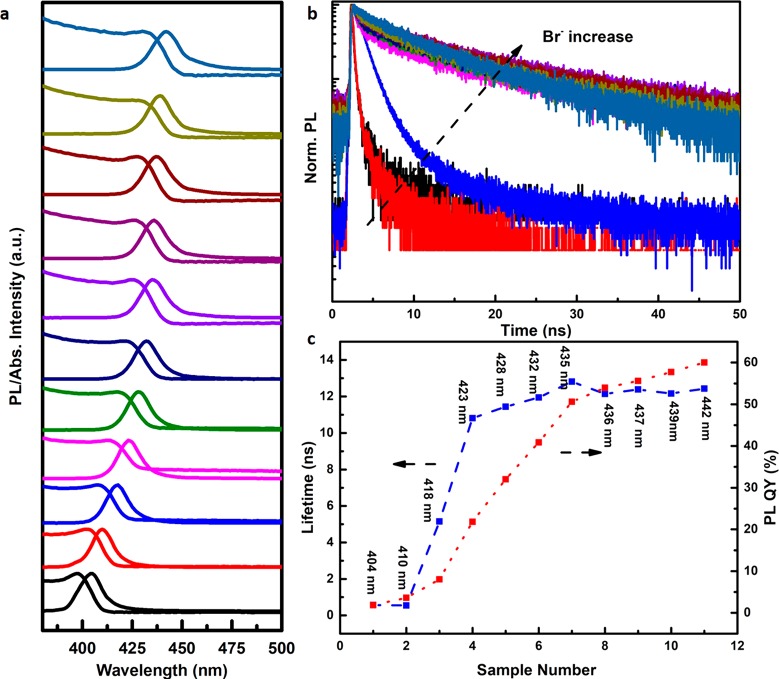

CsPbCl3 NCs of ∼12 nm were used as parent NCs. Addition of bromide precursors into the colloidal solution of CsPbCl3 NCs initiates the Cl– to Br– ion exchange. The halide exchange induces a red-shift of both the absorption onset and exciton emission peak, indicating the narrowing the bandgap as the result of gradual substitution of Cl– by Br–. In Figure 1a, the absorption and emission spectra are shown upon raising the Br– content in CsPbCl3–xBrx from x = 0 (black spectrum, bottom) to x = 1.18 (blue spectrum, top). Fine-tuning of the Br– content results in shift of the absorption onset and emission in the range 400–442 nm. The Br– content x can be estimated based on the position of the exciton emission peak. A continuous shift to longer wavelengths from 404 nm (x = 0) to 420 nm (x = 0.6) to 437 nm (x = 1.1) to 487 nm (x = 2.4).7 Similar shifts are reported in ref (22). On the basis of the known relation between the exciton peak position and Br– content, we determined the Br– content in our samples from the position of the exciton emission peak. The Br– content increases from x = 0 for sample 1 to x = 0.55 for sample 3, x = 0.84 for sample 5, x = 1.07 for sample 8, and x = 1.18 for sample 11. Besides the red-shift of the photoluminescence, with the replacement of Cl– by Br– the PL QY increases and the exciton lifetime is lengthened, as illustrated in Figure 1b,c.

Figure 1.

Evolution of photoluminescence properties of CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs at 300 K as a function of x (x is varied from 0 to 1.18 estimated from the position of the exciton peak). (a) Absorption and emission spectra of CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs with different x (λex = 355 nm). (b) Luminescence decay curves of the exciton emission for CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs plotted on semilogarithm scale (λex = 376 nm, pulse width = 65 ps) (3) PL QY and exciton emission lifetime of CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs upon increasing x. The Br– content can be determined from the position of the exciton emission peak (see refs (7 and 22)) and increases from x = 0 for sample 1 to x = 0.55 for sample 3, x = 0.84 for sample 5, x = 1.07 for sample 8, and x = 1.18 for sample 11.

The origin of the substantial enhancement of PL QY is twofold. First, the addition of a halide source efficiently passivates the surface halide vacancies. Surface halide vacancies provide nonradiative recombination sites (sub-band trap state) which reduce the PL QY of exciton emission.23,24 The origin of halide vacancies is a halide deficiency resulting from the synthesis strategy. In a typical synthesis, PbX2 is used as the halide source and subsequent addition of Cs–oleate triggers the crystallization of CsPbX3 with a metal to halide ratio = 1:1:3 (Cs:Pb:X). Consequently, the Pb2+ ions are in excess and thus contribute to the creation of halide vacancy trap states.25 In addition, the postsynthetic purification contributes to the loss of surface halide ions. Filling of halide vacancies in a halide-rich reaction medium has been shown to enhance the PL QY.26,27 Also for Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs, the PL QY of the exciton emission increases compared to undoped CsPbCl3 NCs synthesized under similar conditions.8 The halide ions introduced by the added MnCl2 contribute to the enhancement of the exciton emission. Furthermore, the position of trap states relative to the bottom of conduction band varies with the halide composition. With the narrowing the bandgap, the density of trap states within the bandgap can decrease substantially, which render NCs with a smaller bandgap more efficient as demonstrated by Kovalenko et al.28 and Yamauchi et al.29 With increasing PL QY the exciton emission lifetime lengthens (Figure 1b), consistent with a reduction in the nonradiative decay rate.

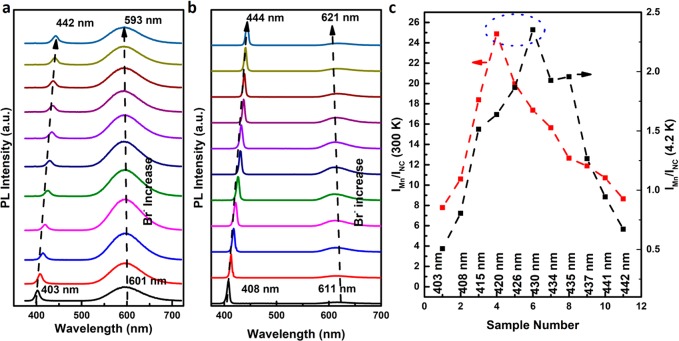

In the subsequent section, we focus on the influence of anion composition on the exciton-to-Mn2+ ET efficiency. The starting Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs were synthesized with a hot-injection method and a 2.8 at. % concentration of Mn2+ which is an optimum concentration to realize high Mn2+ luminescence efficiencies. Exciton-to-Mn2+ ET becomes less efficient for lower doping concentrations while for higher concentrations concentration quenching occurs.16 Representative TEM images and photographs of both doped and undoped CsPbCl3 NCs and an EDX spectrum of doped CsPbCl3 NCs are shown in the Supporting Information (Figure SF1). Similar morphology and size distribution are observed for the Mn2+-doped and undoped CsPbCl3 NCs (cubic, with edge length of ∼12 nm). PL properties of Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs resemble their undoped counterpart with a few noteworthy differences. For Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs, a slight blue-shift of the absorption spectrum is noticed and ascribed to an alloying effect. Replacement of Pb2+ by the smaller and more ionic Mn2+ ion results in a widening of the bandgap with increasing Mn2+ content7 similar to the widening of the bandgap observed for Mn-doped CdSe QDs.30 The loss of sharpness of the absorption spectrum at the onset reflects the statistical nature of dopant inclusion within the ensemble of NCs. To explore the influence of replacement of Cl– by Br–, a series of samples with various Br/Cl ratios were synthesized by a facile postsynthetic anion exchange using octylammonium bromide (oct-bromide) as bromide precursor. Oct-bromide is a Pb-free Br-precursor, and its use allows for anion exchange without loss of Mn2+ from the NCs during the exchange reaction.7 On the contrary, using PbBr2 as a Br– source has been shown to result in Mn2+ loss.7 Samples with various Br/Cl ratios have nearly identical morphology and size dispersity. No broadening of the exciton emission peak is observed which serves as evidence for the formation of homogeneous final products. The use of a halide–ammonium precursor (unlike PbX2, X = Cl, Br, I) avoids a role of cation exchange accompanying anion exchange and allows for a meaningful comparison between different samples. To carefully probe the role of the Br/Cl ratio, 11 samples were studied for x = 0 (no Br–) to x = 1.18. The exact Br– content was not determined as it is difficult to completely wash away all precursor materials. The continuous shift of the exciton emission line from 404 to 442 nm shows a continuously increasing Br– content in the series of samples. The Br– content x was estimated based on the position of the exciton emission peak just as for the undoped CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs and increases from x = 0 for sample 1 to x = 0.42 for sample 3, x = 0.79 for sample 5, x = 1.04 for sample 8, and x = 1.18 for sample 11. The normalized emission spectra of the CsPbCl3–xBrx:Mn2+ samples at 300 and 4.2 K are shown in Figures 2a and 2b (for absorption spectrum and calibrated emission spectra at 300 K, see Figure SF2a). While the exciton emission red-shifts to longer wavelengths upon increasing the Br– content, a small but consistent blue-shift of Mn2+ emission (from 601 to 593 nm as x is increased from 0 to 1.18) is clearly observed with increasing Br– fraction. A similar blue-shift of the Mn2+ emission upon increasing the Br– content was recently reported in ref (19). The blue-shift is attributed to lattice expansion due to exchange of the smaller Cl– by larger Br– anions which results in a weaker of the crystal field. In the Tanabe–Sugano (3d5) diagram of Mn2+ it is evident that the 4T1 excited state shifts to higher energies for a weaker crystal field which explains the observed blue-shift.

Figure 2.

Evolution of emission spectra as the function of Br– content in 2.8% Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs (λex = 355 nm) at (a) 295 K and (b) 4.2 K. (c) Evolution of the Mn2+-to-exciton integrated emission intensity ratio with x at 300 K (red curve) and 4.2 K (black curve) as determined from the spectra in panels a and b. The Br– content can be determined from the position of the exciton emission peak (see refs (7 and 22)) and increases from x = 0 for sample 1 to x = 0.42 for sample 3, x = 0.79 for sample 5, x = 1.04 for sample 8, and x = 1.18 for sample 11.

To investigate the influence of the Br/Cl ratio on the exciton-to-Mn2+ ET efficiency, the ratio of the Mn2+ to exciton emission intensities (IMn/IExc) was determined from the spectra in Figures 2a and 2b. In Figure 2c the ratio is plotted for the series of samples both at 300 and 4.2 K. IMn/IExc initially increases with Br– content. At 300 K, a significant 3-fold increase is observed upon substitution of Cl– by Br– reaching a maximum ratio of 26 for the sample showing exciton emission at 420 nm. The subsequent decrease upon further Cl– to Br– substitution results is a ratio of ∼8 for x = 1.18 (sample 11), similar to the ratio observed in the CsPbCl3:Mn2+ sample (x = 0).

In analogy with previous work on dual emission in Zn1–xMnxSe/ZnCdSe QDs, the PL intensities of exciton (IExc) and Mn2+ (IMn) are described using eqs 1 and 2.31 The emission intensities are determined by the total generation rate (G), nonradiative and radiative decay rate for the emitting excitonic states in the NCs (knrExc, kr) and Mn2+ (knrMn, kr), forward and back energy transfer rates (kET, kBET), and the populations of ground state (Ngs), excited state of Mn2+ (NMn), and nanocrystal (NNC).

| 1 |

| 2 |

Upon creation of an exciton in Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs, several relaxation mechanisms are active. Charge carrier trapping at surface-related trap states accounts for the decreased PL QY and shortening of exciton lifetime and contributes to knrExc. For Mn2+-doped NCs a competing de-excitation pathway is exciton-to-Mn2+ energy transfer. Compared to II–VI Mn2+-doped NCs, ET to Mn2+ in Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs is slow, which is attributed to the highly ionic nature of the NCs. Typical exciton to Mn2+ energy transfer rates kET in CsPbCl3 NCs are in the 0.3–3 ns–1 range,8,15 more than an order of magnitude slower than in Zn1–xMnxSe/ZnCdSe.32,33 This slow ET explains the coexistence of exciton and Mn2+ emission even in heavily Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs. The nonradiative decay rate of excited Mn2+ (knr) is usually neglected as Mn2+ luminescence quenching is limited as evidenced by a single-exponential decay with a millisecond decay time, typical of the radiative lifetime for Mn2+ emission (Figure SF3).

To understand the variation of the Mn2+ to exciton emission intensity ratios, competition between all possible decay processes needs to be considered, i.e., radiative and nonradiative decay of the exciton as well as forward and back energy transfer between exciton and Mn2+. As discussed above, for undoped CsPbCl3 a substantial increase in the PL QY is observed for the exciton emission during the Cl– to Br– anion exchange process by elimination of surface trap states which reduces nonradiative exciton decay and turns on dark NCs. The fast nonradiative decay will compete with both exciton emission and energy transfer to Mn2+ in Mn2+-doped NCs. Upon anion exchange the addition of Br– anions leads to passivation of surface states and causes a decrease in the direct nonradiative decay channel. The decrease in the nonradiative decay rate for the exciton emission that accompanies the anion exchange process cannot explain the increase in the relative intensity of the Mn2+ emission as it would mostly enhance the exciton emission intensity. Nonradiative ET to surface trap states is fast and is expected to dominate in NCs with surface trap states. It is responsible for a decrease in the overall emission intensity. The relative intensities of exciton and Mn2+ emission are determined by competition between the radiative decay rate of the exciton emission and the ET rate to Mn2+. The increase in ratio of the Mn2+-to-exciton emission intensity ratio upon substitution of Cl– by Br– therefore reflects the change in ratio between the radiative exciton decay rate (krExc) and the energy transfer rate to Mn2+ (kET). The observed increase in the relative intensity of the Mn2+ emission can be explained by two effects: (1) the radiative exciton decay rate decreases with increasing Br– content and (2) the exciton-to-Mn2+ ET rate increases. A decrease of the radiative decay rate of exciton emission both at room temperature and at cryogenic temperatures has been reported from CsPbCl3 to CsPbBr3 to CsPbI3.4,34 The influence of chemical composition on the exciton-to-Mn2+ transfer rate is not well established. It is clear that the ET efficiency is low in comparison to the II–VI semiconductor QDs where ∼20 ps transfer times have been observed.32 The slow nanosecond ET in CsPbCl3 has been attributed to the ionic character of the perovskite NCs. In addition, the larger size of the perovskite NCs (typically ∼10 nm) in comparison with the II–VI QDs (3–6 nm) will reduce wave function overlap and thus reduce the ET rate. Substitution of Cl– with Br– will increase the host covalency and can qualitatively explain the observed increase in ET rate.

Following the initial strong increase of IMn/IExc with the fraction of Br– ions, a sharp decrease of the relative Mn2+ emission intensity is observed upon further raising the Br– content, in the regime where the exciton emission shifts from 420 to 442 nm. This cannot be explained by a change in krExc (which expected to continue to decrease with Br– content) or kET (which will continue to increase with Br– content). However, as the bandgap narrows with increasing Br– content, back-transfer from Mn2+ to the exciton can occur. As the radiative decay rate of the exciton emission is about 106 times higher than the slow (milliseconds, spin- and parity-forbidden) Mn2+ emission, already for small thermal population levels back-transfer will result in dominant exciton emission. The situation is analogous to that for CdSe:Mn2+. In small CdSe QDs (large bandgap) fast trapping of the exciton results in dominant Mn2+ emission. In larger QDs with a narrower bandgap, the proximity of the Mn2+ excited states and the band edge of the CdSe QDs results in efficient back-transfer from Mn2+ to the exciton, giving strongly temperature-dependent Mn2+ and exciton emission intensities.33 The back energy transfer is a thermally activated processes with a rate proportional to the exp(−Ea/kBT) in which the activation energy Ea is the energy separation between the band edge and the emitting state of Mn2+. The activation barrier Ea is reduced with the progressive exchange of Cl– by Br–, and hence the thermally activated back energy transfer becomes more pronounced and causes a reduction in the IMn/IExc emission intensity ratio. The back energy transfer is also collaborated by the time-resolved PL measurement of Mn2+. The shortening of excited lifetime of Mn2+ with increasing of bromide fraction (decreasing of Ea) provides additional experimental evidence of back energy transfer (for decay curves, see Figure SF3). Note that also enhanced spin–orbit interaction through the replacement of chlorine by heavier bromide contributes to faster decay of Mn2+ emission (heavy atom effect, coordination with heavy ligands enhances spin–orbit coupling to relax the spin-selection rule for spin-forbidden transitions).

To obtain further information on the competition between exciton emission and exciton-to-Mn2+ ET as a function of host composition in CsPbCl3–xBrx, photoluminescence measurements were conducted in liquid helium (4.2 K, Figure 2b). At cryogenic temperatures thermally activated quenching by trap (surface) states is reduced, and the relative intensities of the Mn2+ and exciton emission (IMn/IExc) more closely reflect the composition dependence of kET/krExc. The evolution of intensity ratio of various samples at 4.2 K is depicted in the Figure 2c. A similar trend is found as for the measurements at 295 K. An initial increase of the intensity ratio is followed by a decrease, now starting at a sample with a higher Br– content (exciton emission at 430 nm). The absolute values of the intensity ratios IMn/IExc are about 10 times smaller at 4.2 K. The higher relative intensity of the exciton emission and can be understood from the much faster radiative decay rate kr of the exciton emission at 4.2 K.34 Contrary to other QDs (e.g., II–VI and IV–VI), the lowest exciton state is a bright state for CsPbX3 perovskite nanocrystals with an order of magnitude faster decay rate than higher energy exciton states which are thermally populated at room temperature.34 The higher value for krExc at 4.2 K and a similar value for kET explain the large difference in IMn/IExc between 4.2 and 300 K.

The composition dependence shows that upon raising the Br– content in the CsPbCl3–xBrx:Mn2+ NCs again an initial increase in IMn/IExc is followed by a sharp decrease. The transition point has shifted to a higher Br– content (i.e., smaller bandgap). This is consistent with back-transfer as the mechanism responsible for the decrease in IMn. At RT thermally activated back-transfer occurs when the Mn2+ excited state is close to the NC edge state. The energy difference between the transition points at 4.2 and 300 K (430 vs 420 nm) correspond to a difference in host bandgap of ∼550 cm–1, close to ∼3 kT at 300 K. The 4.2 K measurements pinpoint the composition where the Mn2+ excited state is resonant with band states of the CsPbCl3–xBrx NCs which emit at 430 nm since at 4 K thermally activated back-transfer can be neglected, and the Mn2+ excited state can only transfer to states at the same or lower energies.

Back-transfer from excited d-states to the conduction band becomes possible when the d-states overlap in energy with the continuum of band states of the valence or conduction band.35−37 The position of the ground state relative to the band edges is crucial. If the ground state is resonant with the valence band edge, the exciton emission and dopant emission need to be close in energy. However, if the ground state is situated above the valence band edge, back-transfer from excited d-states to conduction band states can occur when the dopant emission is lower in energy than the exciton emission. With an electronic origin of the Mn2+ d–d emission band around 550 nm and substantial quenching of the Mn2+ emission for NCs with exciton emission around 440 nm, the energy mismatch of ∼0.5 eV corresponds to the energy difference between the Mn2+ ground state and the top of the valence band.

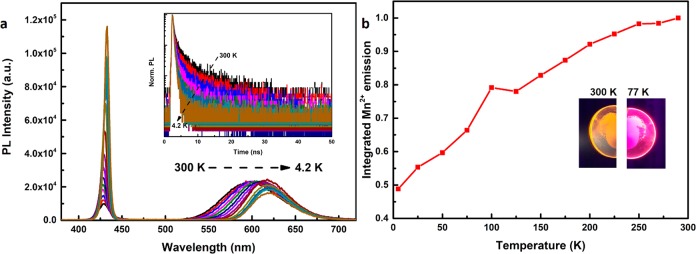

It is also insightful to investigate the temperature dependence of the luminescence properties. In Figure 3, the temperature-dependent emission, luminescence decay curves, and absolute Mn2+ emission intensities are shown for the mixed CsPbCl3–xBrx:Mn2+ sample with the highest relative Mn2+ emission intensity at 4.2 K (430 nm exciton emission). The exciton emission shows a small but consistent shift to longer wavelengths (red-shift) from 430 nm at 300 K to 435 nm at 4.2 K. For most semiconductors a blue-shift is observed upon cooling and is described by the empirical Varshni equation.38 Just as for CsPbX3 NCs, also for PbX (X = S, Se, Te) QDs an anomalous red-shift has been reported upon cooling and has been explained by competing influences on the bandgap energy, related to lattice contraction and freezing out of lattice vibrations upon lowering of T.39 It will be interesting to conduct further research to elucidate the mechanism behind the anti-Varshni behavior in Pb-containing semiconductors NCs. The Mn2+ emission also shows a marked red-shift from 588 nm at 300 K to 615 nm at 4.2 K. This red-shift is explained by lattice contraction. The position of emission peak of Mn2+ is largely determined by the crystal field splitting (Dq) which increases as the distance between Mn2+ and coordinating ligands (here Cl– and Br– anions) decreases. Lowering the temperature gives lattice contraction and enhances the crystal field splitting. In the Tanabe–Sugano diagram for the 3d5 configuration it is clear that the 4T1 excited state of Mn2+ from which the orange emission originates is lowered in energy for a higher crystal field, and this explains a red-shifted Mn2+ emission upon lattice contraction.

Figure 3.

Temperature-dependent luminescence of CsPbCl3–xBrx:Mn2+ 2.8% for sample of exciton emission wavelength 430 nm (x = 0.90). (a) Emission spectra at different temperature (λex = 355 nm). Inset: luminescence decay curves of the exciton emission (λex = 376 nm, pulse width: 65 ps). (b) Evolution of integrated Mn2+ emission with temperature. The inset shows a photograph of the sample at 300 and 77 K under illumination with a hand-held UV lamp emitting 365 nm UV radiation. The color shift reflects the much higher relative intensity of the exciton emission at 77 K compared to 300 K.

The temperature-dependent decay kinetics of the exciton emission (inset, Figure 3a) show the increasingly fast decay upon lowering the temperature. The average decay time decreases from 1.7 ns at 300 K to 0.7 ns at 4.2 K. The faster decay can be explained by the higher radiative decay rate from the lowest (bright) exciton state. The low-temperature decay times observed are limited by the time resolution of the experimental setup (∼0.5 ns). The absolute intensity of the Mn2+ emission (Figure 3b) shows a continuous reduction upon cooling and decreases by a factor of 2 between 300 and 4.2 K. For Mn2+-doped CsPbCl3 NCs (the parent NCs), the integrated PL intensity of Mn2+ at 4.2 K decreased more strongly, by a factor of ∼3 compared to 300 K. An even more substantial decrease was reported by Gamelin et al.,16 who observed a 5-fold decrease of the Mn2+ intensity upon cooling to 80 K. The origin of these differences is in the larger kET/kr ratio for the bromine-rich samples which enhances the Mn2+ emission and gives rise to brighter Mn2+ emission at 4.2 K. The variations between samples reflect differences in nonradiative decay rate (surface defects) which affect the absolute emission intensities, especially at 300 K, and thus contribute to how absolute emission intensities vary. The situation in the perovskite nanocrystals is vastly different from that in II–VI QDs where a strong increase in Mn2+ emission is observed upon cooling. The highly efficient trapping of excitons by the Mn2+ dopants gives rise to dominant Mn2+ emission. Both nonradiative decay rates and back-transfer rates from Mn2+ to the exciton are reduced at low temperature in Mn2+-doped II–VI QDs and give rise to strongly enhanced Mn2+ emission at cryogenic temperatures.

A more quantitative analysis of the exciton emission decay curves shows that the average decay rates of undoped (emission wavelength: 432 nm) and doped samples (emission wavelength: 430 nm) are 1.1 ns–1 (krExc) and 3.7 ns–1 (kr + kET), respectively, at 4.2 K. This enables us to calculate kET to be approximately 2.6 ns–1, and hence the kET/krExc is 2.5, which is in good agreement with the branching ratio from steady-state luminescence measurement of 2.4. Even though good agreement is obtained, it is important to realize that the calculated energy transfer rate is a rough estimate as the time scale of 0.7 ns is approaching the time response of the system (∼0.5 ns).

Conclusions

In summary, the composition and temperature dependence of Mn2+ to exciton emission intensity ratios have been investigated for mixed halide CsPbCl3–xBrx perovskite NCs (x = 0 to ∼1.18). Slow (approximately nanoseconds) exciton-to-Mn2+ transfer times are observed, consistent with earlier reports. The transfer efficiency can be controlled by the Br/Cl ratio. Initial substitution of Cl– by Br– enhances the efficiency through a combined effect of slower exciton decay and faster energy transfer. As the bandgap narrows upon further substitution of Br–, back energy transfer from Mn2+ to host band states sets in and results in a strong reduction of the relative Mn2+ emission intensity. At cryogenic temperatures the energy transfer efficiency is reduced, which is explained by the faster radiative exciton decay from the lowest energy bright exciton state. Again, faster energy transfer is observed upon substituting Cl– by Br– reaching a maximum efficiency for compositions with an exciton emission at 430 nm. The new insights into the exciton-to-Mn2+ energy transfer pinpoint the position of the Mn2+ excited state relative to the CsPbCl3–xBrx band states and predict the temperature- and composition-dependent optical properties of Mn2+-doped halide perovskite NCs.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by China Scholarship Council-Utrecht University PhD Program (Program: 201404910557). The authors also thank Xiaobin Xie for his assistance with TEM measurements.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b02157.

Experimental section; additional spectra; TEM images (PDF)

Author Contributions

K.Y.X. designed the synthesis method and performed the synthesis and characterization. A.M. revised the manuscript and supervised the project. K.Y.X. wrote the first version of the manuscript, and all authors discussed the results and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rosales B. A.; Hanrahan M. P.; Boote B. W.; Rossini A. J.; Smith E. A.; Vela J. Lead Halide Perovskites: Challenges and Opportunities in Advanced Synthesis and Spectroscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 906–914. 10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M.; Quan L. N.; Comin R.; Walters G.; Sabatini R.; Voznyy O.; Hoogland S.; Zhao Y.; Beauregard E. M.; Kanjanaboos P.; Lu Z.; Kim D. H.; Sargent E. H. Perovskite Energy Funnels for Efficient Light-Emitting Diodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 872–877. 10.1038/nnano.2016.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R. J.; Eperon G. E.; Miranda L.; Parrott E. S.; Kamino B. A.; Patel J. B.; Hörantner M. T.; Johnston M. B.; Haghighirad A. A.; Moore D. T.; Snaith H. J. Tunable Cesium Lead Halide Perovskites with High Thermal Stability for Efficient Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1502458–1502463. 10.1002/aenm.201502458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Protesescu L.; Yakunin S.; Bodnarchuk M. I.; Krieg F.; Caputo R.; Hendon C. H.; Yang R.; Walsh A.; Kovalenko M. V. Nanocrystals of cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I): novel optoelectronic materials showing bright emission with wide color gamut. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 3692–3696. 10.1021/nl5048779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.; Li J.; Li X.; Xu L.; Dong Y.; Zeng H. Quantum dot light-emitting diodes based on inorganic perovskite cesium lead halides (CsPbX3). Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7162–7167. 10.1002/adma.201502567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Wu Y.; Zhang S.; Cai B.; Gu Y.; Song J.; Zeng H. CsPbX3 quantum dots for lighting and displays: room temperature synthesis, photoluminescence superiorities, underlying origins and white light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 2435–2446. 10.1002/adfm.201600109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Lin Q.; Li H.; Wu K.; Robel I.; Pietryga J. M.; Klimov V. I. Mn2+-Doped lead halide perovskite nanocrystals with dual-color emission controlled by halide content. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14954–14961. 10.1021/jacs.6b08085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parobek D.; Roman B. J.; Dong Y.; Jin H.; Lee E.; Sheldon M.; Son D. Exciton-to-dopant energy transfer in Mn-doped cesium lead halide perovskite nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 7376–7380. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Wu Z.; Shao J.; Yao D.; Gao H.; Liu Y.; Yu W.; Zhang H.; Yang B. CsPbxMn1–xCl3 perovskite quantum dots with high Mn substitution ratio. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 2239–2247. 10.1021/acsnano.6b08747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K.; Lin C.; Xie X.; Meijerink A. Efficient and stable luminescence from Mn2+ in core and core-isocrystalline shell CsPbCl3 perovskite nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 4265–4272. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D.; Liu D.; Pan G.; Chen X.; Li D.; Xu W.; Bai X.; Song H. Cerium and Ytterbium Codoped Halide Perovskite Quantum Dots: A Novel and Efficient Downconverter for Improving the Performance of Silicon Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1704149–1704154. 10.1002/adma.201704149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G.; Bai X.; Yang D.; Chen X.; Jing P.; Qu S.; Zhang L.; Zhou D.; Zhu J.; Xu W.; Dong B.; Song H. Doping Lanthanide into Perovskite Nanocrystals: Highly Improved and Expanded Optical Properties. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 8005–8011. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Zhang X.; Jin Z.; Zhang J.; Gao Z.; Li Y.; Liu S. Energy-down-shift CsPbCl3:Mn Quantum dots for boosting the efficiency and stability of perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1479–1486. 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meinardi F.; Akkerman Q. A.; Bruni F.; Park S.; Mauri M.; Dang Z.; Manna L.; Brovelli S. Doped Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals for Reabsorption-Free Luminescent Solar Concentrators. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 2368–2377. 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D.; Parobek D.; Dong Y.; Son D. H. Dynamics of Exciton-to-Mn Energy Transfer in Mn doped CsPbCl3 Perovskite Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 17143–17149. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b06182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X.; Ji S.; De Siena M. C.; Fei L.; Zhao Z.; Wang Y.; Li H.; Zhao J.; Gamelin D. R. Photoluminescence Temperature Dependence, Dynamics, and Quantum Efficiencies in Mn2+-Doped CsPbCl3 Perovskite Nanocrystals with Varied Dopant Concentration. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 8003–8011. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b03311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; Fang G.; Chen X. Silica-Coated Mn-Doped CsPb(Cl/Br)3 Inorganic Perovskite Quantum Dots: Exciton-to-Mn Energy Transfer and Blue-Excitable Solid-State Lighting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 40477–40487. 10.1021/acsami.7b14471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.-Y.; Maiti S.; Son D. H. Doping Location-Dependent Energy Transfer Dynamics in Mn-Doped CdS/ZnS Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 583–591. 10.1021/nn204452e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Xia Z. G.; Pan C. F.; Gong Y.; Gu L.; Liu Q. L.; Zhang J. Z. High Br- Content CsPb(ClyBr1-y)3 Perovskite Nanocrystals with Strong Mn2+ Emission through Diverse Cation/Anion Exchange Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 11739–11746. 10.1021/acsami.7b18750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu G.; Protesescu L.; Yakunin S.; Bodnarchuk M. I.; Grotevent M.; Kovalenko M. V. Fast anion-exchange in highly luminescent nanocrystals of cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, I). Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 5635–5640. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkerman Q. A.; D’Innocenzo V.; Accornero S.; Scarpellini A.; Petrozza A.; Prato M.; Manna L. Tuning the Optical Properties of Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals by Anion Exchange Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10276–10281. 10.1021/jacs.5b05602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Xia Z. G.; Gong Y.; Gu L.; Liu Q. L. Optical properties of Mn2+ doped Cesium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals via Cation-Anion Co-substitution Exchange Reaction. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 9281–9287. 10.1039/C7TC03575F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diroll B. T.; Nedelcu G.; Kovalenko M. V.; Schaller R. D. High-Temperature Photoluminescence of CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) Nanocrystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1606750–1606756. 10.1002/adfm.201606750. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noel N. K.; Abate A.; Stranks S. D.; Parrott E. S.; Burlakov V. M.; Goriely A.; Snaith H. J. Enhanced Photoluminescence and Solar Cell Performance via Lewis Base Passivation of Organic–Inorganic Lead Halide Perovskites. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 9815–9821. 10.1021/nn5036476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Chen W.; Wang W.; Xu B.; Wu D.; Hao J.; Cao W.; Fang F.; Li Y.; Zeng Y.; Pan R.; Chen S.; Cao W.; Sun X. W.; Wang K. Halide-Rich Synthesized Cesium Lead Bromide Perovskite Nanocrystals for Light-Emitting Diodes with Improved Performance. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 5168–5173. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasio F.; Christodoulou S.; Huo N.; Konstantatos G. Near-Unity Photoluminescence Quantum Yield in CsPbBr3 Nanocrystal Solid-State Films via Postsynthesis Treatment with Lead Bromide. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 7663–7667. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.; Yang Y.; Bekenstein Y.; Yu Y.; Gibson N. A.; Wong A. B.; Eaton S. W.; Kornienko N.; Kong Q.; Lai M.; Alivisatos P. A.; Leone S. R.; Yang P. Synthesis of composition tunable and highly luminescent cesium lead halide hanowires through anion-exchange reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7236–7239. 10.1021/jacs.6b03134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirin D. N.; Protesescu L.; Trummer D.; Kochetygov I. V.; Yakunin S.; Krumeich F.; Stadie N. P.; Kovalenko M. V. Harnessing Defect-Tolerance at the Nanoscale: Highly Luminescent Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals in Mesoporous Silica Matrices. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 5866–5874. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malgras V.; Tominaka S.; Ryan J. W.; Henzie J.; Takei T.; Ohara K.; Yamauchi Y. Observation of Quantum Confinement in Monodisperse Methylammonium Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals Embedded in Mesoporous Silica. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 13874–13881. 10.1021/jacs.6b05608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaskin V. A.; Barrows C. J.; Erickson C. S.; Gamelin D. R. Nanocrystal Diffusion Doping. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14380–14389. 10.1021/ja4072207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulac R.; Ochsenbein S. T.; Gamelin D. R.. Colloidal Transition Metal-Doped Quantum Dots. In Nanocrystal Quantum Dots, 2nd ed.; Klimov V. I., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2010; pp 432–433. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaskin V. A.; Janssen N.; van Rijssel J.; Beaulac R.; Gamelin D. R. Tunable Dual Emission in Doped Semiconductor Nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3670–3674. 10.1021/nl102135k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulac R.; Archer P. I.; van Rijssel J.; Meijerink A.; Gamelin D. R. Exciton Storage by Mn2+ in Colloidal Mn2+-Doped CdSe Quantum Dots. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 2949–2953. 10.1021/nl801847e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M. A.; Vaxenburg R.; Nedelcu G.; Sercel P. C.; Shabaev A.; Mehl M. J.; Michopoulos J. G.; Lambrakos S. G.; Bernstein N.; Lyons J. L.; Stöferle T.; Mahrt R. F.; Kovalenko M. V.; Norris D. J.; Rainò G.; Efros A. L. Bright Triplet Excitons in Caesium Lead Halide Perovskites. Nature 2018, 553, 189–193. 10.1038/nature25147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos J. J.; Poelman D.; Smet P. F. Energy Level Modeling of Lanthanide Materials: Review and Uncertainty Analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 19058–19078. 10.1039/C5CP02156A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E. G.; Dorenbos P. Vacuum Referred Binding Energy of the Single 3d, 4d, or 5d Electron in Transition Metal and Lanthanide Impurities in Compounds. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, R173–R184. 10.1149/2.0121410jss. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorenbos P. Absolute Location of Lanthanide Energy Levels and the Performance of Phosphors. J. Lumin. 2007, 122-123, 315–317. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2006.01.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varshni Y. P. Temperature Dependence of the Energy Gap in Semiconductors. Physica 1967, 34, 149–154. 10.1016/0031-8914(67)90062-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shinde A.; Gahlaut R.; Mahamuni S. Low-Temperature Photoluminescence Studies of CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 14872–14878. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b02982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.