Abstract

As the most abundant and reversible RNA modification in eukaryotic cells, m6A triggers a new layer of epi‐transcription. M6A modification occurs through a methylation process modified by “writers” complexes, reversed by “erasers”, and exerts its role depending on various “readers”. Emerging evidence shows that there is a strong association between m6A and human diseases, especially cancers. Herein, we review bi‐aspects of m6A in regulating cancers mediated by the m6A‐associated proteins, which exert vital and specific roles in the development of various cancers. Generally, the m6A modification performs promotion or inhibition functions (dual role) in tumorigenesis and progression of various cancers, which suggests a new concept in cancer regulations. In addition, m6A‐targeted therapies including competitive antagonists of m6A‐associated proteins may provide a new tumour intervention in the future.

Keywords: ALKBH5, cancer, epigenetics, FTO, METTL3, N6‐methyladenosine (m6A)

1. INTRODUCTION

Epigenetics, a branch of genetics with stable heritable traits, is defined as the functionally relevant changes or gene expression alteration based on DNA methylation, histones modification, chromatin remodelling, gene silencing, RNA modification, etc.1 There are several identified epigenetic modifications, paving the way for cell growth, differentiation, self‐renewal and division. A common epigenetic mark is 5‐methylcytosine,2 which has been termed the “fifth base” with potential functions on the control and regulation of gene transcription and protein translation by recruiting DNA‐binding proteins.2, 3 Similarly, a multitude of modifications, termed as epi‐transcriptomics, are identified on RNA from all three kingdoms of life.4 They are N6‐methyladenosine (m6A), N7‐methylguanosine, 5‐methylcytosine and N1‐methyladenosine, etc. Recent studies have illustrated that m6A modification is a highly abundant and conservative RNA modification in eukaryotic cells.5, 6 In addition, changes in m6A modification are observed to be involved in multiple cellular processes, which may have impacts on several human diseases.7, 8 Recently developed methods have enabled researchers to determine the precise location and abundance of m6A residues and their implication in human diseases, especially in cancers.7, 9 Herein, we provide an updated review regarding the critical regulatory effects of m6A modification in several human cancers, and to improve the understanding of mechanisms of tumour carcinogenesis.

2. THE DISCOVERY OF m6A AND ITS FUNCTION

2.1. The discovery of m6A

Despite the early discovery of m6A in 1974, the function and mechanism of m6A were unclear until fat mass and obesity‐associated protein (FTO) was detected to be a demethylase of m6A in 2011.10 Since then, increased attention was paid to the fundamental mechanism and biological function of m6A significantly.10, 11 Alpha‐ketoglutarate‐dependent dioxygenase homolog 5 (ALKBH5), the second RNA demethylase, was first reported in 2013.12 Both FTO and ALKBH5 belong to the alpha‐ketoglutarate‐dependent dioxygenase family and catalyse m6A demethylation in a Fe(II)‐ and alpha‐ketoglutarate‐dependent manner.13, 14 Analogous to ALKBH5, alpha‐ketoglutarate‐dependent dioxygenase homolog 3 (ALKBH3) has been demonstrated demethylase activity for 1‐methyladenine and 3‐methylcytosine.15 Recently, Ueda et al. have reported that m6A was also a substrate of ALKBH3.16 Interestingly, ALKBH3 shows a special substrate preference for RNA, targeting only m6A in tRNA, rather than those in mRNA or rRNA. An early study found two components of m6A methyltransferase in HeLa cells, termed as MT‐A and MT‐B.17 Subsequently in 1997, a subunit of MT‐A was identified and termed as methyltransferase‐like protein 3 (METTL3).18 However, it was until in 2013 that methyltransferase‐like protein 14 (METTL14), the second component of methyltransferase, was identified. Besides, METTL3 and METTL14 belong to two separate families, but are highly homogenous.19 Shortly following this identification, Wilms’ tumour 1‐associating protein (WTAP) was identified with the function of supporting the heterodimer core complex of METTL3‐METTL14 to localize into nuclear speckles.20 An additional observation in 2014 interestingly demonstrated that KIAA1429 (also known as VIRMA) was substantially required for complete methylation.21 After that, researchers found the depletion of VIRMA led to the largest reduction in mRNA methylation among the known writers.22 And further studies indicate that VIRMA is engaged in recruiting METTL3‐METTL14‐WTAP at specific site and HAKAI is also an important component of methyltransferase. Besides, ZC3H13 plays a role in anchoring the m6A regulatory complex in the nucleus.23 Additionally, Jaffrey et al. demonstrated two previously unrecognized components of the m6A methylation complex, namely RNA‐binding motif protein 15 (RBM15) and its paralogue RBM15B, in 2016.24 And METTL16 is also regarded as the methyltransferase that modifies U6 snRNAs and various non‐coding RNAs.25, 26 To date, the supposed core component of m6A methyltransferase is METTL3‐METTL14‐WTAP‐VIRMA‐HAKAI‐ZC3H13.

The YTH domain family, with its RNA‐binding domains, was the first identified “reader”. Wang et al. indicated that YTH domain family protein 2 (YTHDF2) selectively bound to m6A‐containing mRNA, subsequently reducing the stability of the target transcripts and affecting the degradation of the mRNA.4 In contrast, YTH domain family protein 1 (YTHDF1) exerts its role in promoting translation efficiency.27 In the meantime, the role of YTH domain‐containing protein 1 (YTHDC1) in regulating mRNA splicing has been revealed.28, 29 In 2017, Shi et al. showed that YTH domain family protein 3 (YTHDF3) promoted translation in synergy with YTHDF1 and affected methylated mRNA decay mediated through YTHDF2.30 And recently, researchers have found that YTHDC2 promotes translation efficiency and decreases the mRNA abundance.31 Apart from the YTH domain family, certain proteins in the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein family also act as “readers”. In 2015, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2‐B1 (HNRNPA2B1) was first determined to bind to m6A‐containing miRNA transcripts and promote primary miRNA processing.32 Additionally, it was also found that the binding process between heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein C (HNRNPC) and substrate RNA was partially mediated by m6A modification.33

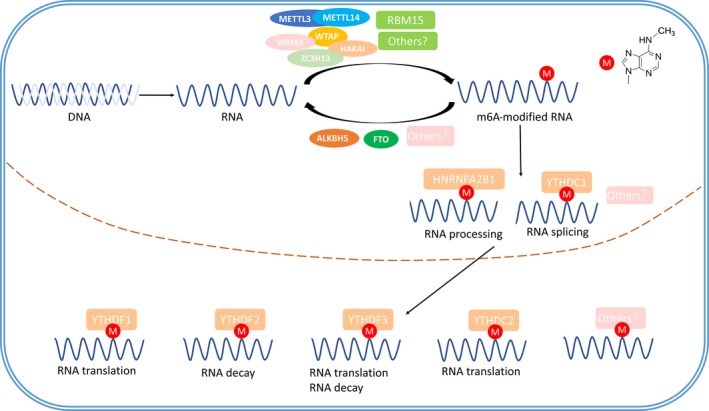

Following investigations of the m6A‐associated proteins complex, we conclude that there is a dynamic reversible process which is composed of the methyltransferase complex, independent demethylases and function executives. The methyltransferases, also known as “writers”, catalyse RNAs to promote and produce methylation at the N6 position of adenosine, and consist of METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, RBM15, VIRMA, HAKAI and ZC3H13. The demethylases, called “erasers”, conversely remove methyl groups to reverse the m6A modification and are composed of FTO and ALKBH5. The final function executions are mediated by variable “readers” to determine different downstream effects by recognizing m6A sites. Readers include YTHDF1/2/3, YTHDC1/2 and HNRNPA2B1. The whole progression of m6A is summed up in Figure 1. However, additional studies need to be conducted in this area to determine other related proteins and specific regulatory mechanisms.

Figure 1.

M6A modification‐associated proteins and the modification pathways. The methyltransferases (METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, VIRMA, HAKAI, ZC3H13 and RBM15) catalyse RNAs to produce methylation at the N6 position of adenosine, and the demethylases (FTO and ALKBH5) conversely remove methyl groups. Nuclear readers YTHDC1 and HNRNPA2B1 regulate the RNA processing, and cytoplasmic readers YTHDC2, YTHDF1‐YTHDF3 exert roles in m6A‐containing mRNA translation and decay.

2.2. Methods for detection of m6A in RNAs

M6A methylation is abundant in RNAs, and the total level of m6A in cells could be detected by many methods. They are LC‐MS/MS (liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry), TLC (thin‐layer chromatography), HPLC (high‐performance liquid chromatography), m6A dot blot, etc.7, 12, 19, 34 However, there are issues to be considered, such as the requirement for high‐tech equipment, being not quantitative and too many interference factors.7, 19, 34 And detecting the precise site of m6A in RNA is hindered by the following facts. M6A shares nearly identical chemical properties with adenine, and it is non‐stoichiometric.6 In addition, M6A could also reverse‐transcribe to a thymine and it would not alter the coding capacity of transcripts.6, 14 In 2012, MeRIP‐seq (methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing), also known as M6A‐seq (m6A‐specific methylated RNA immunoprecipitation with next‐generation sequencing), was developed for profiling the transcriptome‐wide m6A distribution.6, 35 In this method, mRNA was fragmented into 100‐nt‐sized oligonucleotides and immunoprecipitated with an m6A‐specific antibody. Libraries were prepared from immunoprecipitated m6A‐containing RNAs and then subjected to next‐generation sequencing. As it relies on RNA fragmentation, its resolution is around 100‐200 nt, making it hard to determine the precise locations of m6A in RNA and losing much stoichiometry information.6, 36 In order to achieve a higher resolution, many methods are developed, such as PA‐m6A‐Seq (photo‐crosslinking‐assisted m6A‐sequencing) and SCARLET (site‐specific cleavage and radioactive‐labelling followed by ligation‐assisted extraction and thin‐layer chromatography).37, 38 However, there still exist problems including time consumption and being unable to be subject to high‐throughput applications.38 Currently, the most effective method probably is MiCLIP (methylation individual nucleotide resolution crosslinking immunoprecipitation), which could detect m6A at precise position. In this method, m6A‐containing RNA is fragmented and crosslinked to anti‐m6A antibody under UV light, then the antibody‐RNA complexes are recovered by protein A/G‐affinity purification and RNA fragments are reverse transcribed, generating mutations or truncations in the resulting cDNA which helps to identify the precise sites of m6A residues.39 Researchers now are equipped with more methods to detect m6A; however, with so many challenges and difficulties, new methods are still in urgent need.

2.3. The biological functions of m6A

The study of m6A is still a nascent field of epigenetics and is currently widely recognized, with growing evidence that its reversible progress controls and determines cell growth and differentiation in regulation of several physiological processes including circadian rhythms,40 spermatogenesis, metabolism, embryogenesis 41 and physical developmental processes.42 Impaired gene regulation plays a critical role in a wide range of disorders. As the most abundant internal and reversible post‐transcriptional modification in mammalian cells, m6A triggers interests in evaluating the correlation between RNA regulation and human diseases. Changes in writers, erasers and readers will also have a profound influence on health. A large number of studies have demonstrated that aberrant m6A modification may lead to a variety of diseases, such as obesity,43 type 2 diabetes mellitus44 and infertility.12 Emerging evidence has indicated that m6A modification plays a significant role in certain cancers. However, the specific regulatory role of m6A in tumorigenesis and cancer progression needs to be fully elucidated. In this review, we will give an overall summary of m6A in the regulation of cancers.

3. THE DUAL ROLE OF m6A MODIFICATION IN HUMAN CANCERS

Accumulating evidence supports the fact that the aberrant level of m6A is strongly associated with a variety of cancers, such as acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), breast cancer, glioblastoma and lung cancer. The m6A‐associated proteins are the dominant factors in the regulation of carcinogenesis and tumour progressions. However, these proteins present a significant tumour specificity in variable tumours, which consequently contributes to the dual role (inhibition or promotion) of m6A modification in cancers. Upon alteration of m6A regulatory genes or a change in expression of proteins related to m6A methylation, the level of m6A on targeting gene mRNA would be dramatically changed and would therefore exert a profound impact on cancer development. In this section, we will systematically review the bi‐aspects of m6A regulating different types of cancers.

3.1. m6A modification inhibits the tumour progression

Emerging evidence has demonstrated that up‐regulation of m6A could inhibit tumour progressions in several types of cancers. Consistently, it was observed that m6A obtained low expression in cervical cancer, and the reduced m6A level was associated with higher FIGO stage and recurrence.45 Further investigation showed that down‐regulation of m6A level induced by interference of METTL3 and METTL14 or overexpression of FTO and ALKBH5 could promote cervical cell proliferation, and vice versa. Herein, we conclude the possible mechanisms about m6A‐associated proteins in other cancers as follows.

3.1.1. METTL3

As an important “writers”, several studies have indicated the tumour suppressor role of METTL3 with up‐regulating m6A modification. However, the role of m6A is controversial in glioblastoma. Glioblastoma is an aggressive primary brain tumour in adults and has no significant improvement in survival rate so far.46 Previous studies strongly indicated the role of m6A methylation in self‐renewal and tumorigenesis of glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs).47 Reduction in m6A level induced by METTL3 silencing led to the up‐regulation of a group of oncogenes such as ADAM19, EPHA3 and KLF4, but a down‐regulation of tumour suppressors including CDKN2A, BRCA2 and TP53I11. Besides, in terms of phenotypes, knockdown of METTL3 promoted GSCs growth and self‐renewal as well as tumour progression, and vice versa.47 It indicated that METTL3 was possibly a tumour suppressor of glioblastoma. However, recently, Visvanathan et al. have discovered powerful but opposite evidence that METTL3‐mediated m6A modification was required for GSCs maintenance.48 The underlying mechanism here is controversial with what we discussed above. The results indicated that METTL3 was up‐regulated in GSCs, whereas METTL3 silencing down‐regulated the glioma reprogramming factors POU3F2, SOX2, SALL2 and OLIG2 and inhibited the growth of GSCs.48 Further RNA immunoprecipitation studies identified that METTL3 methylated specific sites of SOX2‐3′UTR and that the recruitment of HuR to m6A‐modified sites was essential for SOX2 mRNA stabilization. In addition, the characteristic of radio‐resistance in GSCs showed a positive relationship with the level of METTL3, in which SOX2 played a regulatory role.48

3.1.2. METTL14

METTL14 performed tumour suppressor functions similar to that of METTL3 in the development of GSCs by targeting mRNA levels of ADAM19, EPHA3 and KLF4.47 Wang et al. reported that METTL14‐knockdown GSCs showed less demethylation changes as compared to METTL3‐knockdown GSCs.49 For hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the METTL14 expression and m6A level exhibited a converse tendency with the development of HCC, particularly in metastatic HCC. The clinical data also revealed that patients with decreased METTL14 showed worse recurrence‐free survival and overall survival.50 METTL14 deficiency enhanced the metastatic capacity of HCC cells, and conversely, overexpression of METTL14 suppressed cell migration and invasion.50 Further experiments demonstrated that pri‐miR‐126 was a direct target of METTL14 with m6A modification and m6A‐modified pri‐miR‐126 bound to DGCR8 to induce the expression of mature miR‐126 consequently. Induced mature miR‐126 was finally identified as a tumour suppressor.50 It was also discovered that METTL14 presented a markedly decreased tendency in breast cancer50 and miR‐126 was also recognized as a metastasis suppressor of breast cancer,51 which indicated that METTL14 possibly regulated breast cancer by targeting miR‐126 in a m6A‐dependent manner.

3.1.3. FTO

FTO is well recognized for its strong association with increased body mass and obesity.52, 53 Given that obesity is a well‐established risk factor for a wide range of cancers, it is reasonable to postulate that FTO is intimately linked to cancers. In fact, a meta‐analysis revealed that various FTO SNPs were associated with different cancers such as endometrial cancer, pancreatic cancer and breast cancer dependent on or independent of BMI adjustment.54 In addition, aberrant expression or mutation of FTO has been shown to have an intimate link with prostate cancer,55 endometrial cancer56 and breast cancer.57, 58, 59, 60 However, the potential role of FTO as a demethylase remains a nascent yield to be explored. Just recently, the potential role of FTO in cancer initiation and progression by down‐regulating the overall m6A level has been investigated. In this study, Li et al. illustrated that FTO was significantly up‐regulated in certain sub‐types of AMLs such as MLL‐rearranged AML and acute promyelocytic leukaemia.61 Notable enrichment of FTO directly up‐regulated by the oncogenic proteins (e.g. MLL‐fusion proteins, PML‐RARA, FLT3‐ITD and NPM1 mutant) was observed in CD34+ bone marrow cells separated from primary MLL‐rearranged AML patients. Mechanistically, FTO exerted its oncogenic role by targeting the tumour suppressor ASB2 and RARA with its m6A demethylase catalytic activity. Thus, the FTO‐mediated inhibition of the ASB2/RARA axis with decreased overall m6A level markedly contributed to the carcinogenesis of AMLs.61 Recently, researchers have found the antileukaemic activity of R‐2HG, which was the production of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2 and used to be considered as an oncometabolite, and FTO was involved in this progress. To those R‐2HG‐sensitive cells, R‐2HG could enhance the m6A level of MYC/CEBPA mRNA by inhibiting FTO activity. When read by YTHDF2, m6A‐containing mRNA was significantly degraded; thus, the R‐2HG‐FTO‐m6A‐MYC/CEBPA axis greatly suppresses the proliferation of leukaemia cells. And this finding also provides us a promising therapy like the combination of R‐2HG and inhibitor of MYC signalling to cure leukaemia.62

It is also reported that FTO is involved in the progress of glioblastoma development. MA2 is a chemical inhibitor of FTO and could increase m6A level in human cells.63 When treated with MA2, there was a dramatic inhibition of GSCs growth and self‐renewal in vitro, and the sphere formation rates induced by METTL3‐ or METTL14‐knockdown GSCs were also reversed.47

3.1.4. ALKBH5

ALKBH5 is a nuclear 2‐oxoglutarate‐dependent oxygenase and is inducible by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 (HIF‐1) in a large number of cells.64 Intratumoural hypoxia is commonly found in cancers and is an essential microenvironment for cancer progression.65, 66, 67, 68 A recent study has suggested that intratumoural hypoxia is a driving force for breast cancer progression.69 Breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) phenotype is specified by certain core pluripotency factors including NANOG and KLF4, which could be regulated by HIF‐1.70, 71 The above findings led to an investigation of the functional significance of ALKBH5 as an RNA demethylase in cancers. Zhang et al. illustrated that exposure of a subset of breast cancer cells to hypoxia induced ALKBH5 expression in an HIF‐dependent manner, which led to reduction in m6A modification of NANOG mRNA and enhanced NANOG mRNA stability.72 In addition, ALKBH5 depletion impaired hypoxia‐induced BCSCs enrichment and tumour formation.72 Further study showed that ALKBH5 expression was required for breast cancer initiation and lung metastasis.73 Zinc finger protein 217 (also known as ZNF217) plays a complementary role with ALKBH5 in negatively regulating m6A methylation. ZNF217 was identified to function as the m6A methyltransferase inhibitor by sequestering METTL3, consequently promoting the expression and stability of NANOG mRNA and KLF4 mRNA.73 In addition, ZNF217 expression is also induced in an HIF‐dependent manner under hypoxic conditions. Therefore, ZNF217 depletion leads to impaired hypoxia‐induced consistent enrichment of BCSCs with ALKBH5 deficiency.74 In terms of glioblastoma, inactivated ALKBH5 inhibited the proliferation and tumorigenesis of GSCs and impaired GSCs self‐renewal.75 It is widely accepted that FOXM1 plays a pivotal role in regulating GSCs proliferation and self‐renewal.76, 77 ALKBH5 was found to demethylate FOXM1 nascent transcripts and promote FOXM1 expression, whereas long non‐coding RNA antisense of FOXM1 further promoted the interaction of FOXM1 nascent transcripts with ALKBH5. That makes ALKBH5‐FOXM1 important for glioblastoma development.

3.1.5. YTHDF2

YTHDF2 is recognized as a reader protein of m6A methylation and mediates the m6A‐containing mRNA degradation. YTHDF2 was found to be up‐regulated in HCC, and miR‐145 was identified as an upstream regulatory factor to elevate m6A level by targeting YTHDF2 which was consistent with silencing of YTHDF2.78 In addition, YTHDF2 was also found to be significantly up‐regulated in prostate cancer tissues.79 Knockdown of YTHDF2 greatly enhanced the level of m6A and led to the inhibition of proliferation and migration of prostate cancer cells, whereas overexpression of miR‐493‐3p showed similar outcome.79 Further experiment indicated that miR‐493‐3p directly targeted the 3′UTR of YTHDF2, inhibited the YTHDF2‐induced m6A degradation and thus suppressed prostate cancer development. The above observations indicate that YTHDF2 is involved in cancer development by down‐regulating m6A level.

3.1.6. SAM

S‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine (SAM) is the donor of the methylation group in m6A methylation reactions. Enriched abundance of SAM inhibited the growth of breast cancer,80 liver cancer,81, 82 colon cancer83 and gastric cancer cells.84

In summary, carcinogenesis or tumour progression in certain cancers can be significantly inhibited by up‐regulation of m6A modification induced by overexpression of the tumour suppressor “writer” (METTL3 and METTL14) and SAM and silencing of the oncogene “eraser” (FTO and ALKBH5) and “reader”(YTHDF2).

3.2. m6A modification promotes tumour progression

A global view depicts that mutations of m6A regulatory genes were identified in 2.6% of AML, 2.4% of multiple myeloma and 1.0% of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.85 It was also observed that copy number variations (CNVs) appeared in 10.5% of AML patients, among which copy number loss of ALKBH5 was the most frequent. Additionally, 9 of 191 patients showed concomitant copy number gain or loss of more than one m6A regulatory gene. The mutations and CNVs of m6A regulatory genes were associated with poorer cytogenetic risk and other clinic‐pathological or molecular features in AML.85 In addition, impaired m6A regulatory genes were notably associated with the presence of TP53 mutations in AML patients and both might play a complementary role in the maintenance of AML.85 Collectively, it is unknown whether single alteration or multiple changes in m6A modification profoundly affect leukaemia. Huang et al. investigated the DNA and RNA methylation status in circulating tumour cells (CTCs) from lung cancer patients.86 There was a dramatic decrease in 5‐methyl‐2′‐deoxycytidine, but an increase in 5‐methylcytidine and m6A levels in CTCs from lung cancer patients, implying that increased m6A level potentially plays critical roles in tumorigenesis.

3.2.1. METTL3

Regardless of its tumour suppressor role in glioblastoma, certain studies depict that METTL3 promotes cell growth, survival and invasion in several cancers. One study suggested that silencing of METTL3 in HepG2 cells was strongly associated with a noteworthy enhancement of the p53 signalling pathway.6 In addition, it was observed that METTL3 was drastically up‐regulated in HCC patients, with a positive correlation with the higher grade of HCC.87 Tumour suppressor SOCS2 was observed to be the direct downstream target of METTL3. YTHDF2 directly recognized higher m6A modification of SOCS2 mRNA mediated by METTL3, which subsequently induced degradation of SOCS2.88 Consistently, knockdown of SOCS2 drastically enhanced HCC proliferation. Collectively, up‐regulation of METTL3 suppresses the expression of SOCS2 and promotes HCC development through m6A modification. HBXIP is commonly identified as an oncogene and exerts a profound effect on breast cancer.89, 90 A recent study has found that there was a strongly positive association between HBXIP and METTL3.91 Overexpression of HBXIP could significantly elevate the expression of METTL3 in breast cancer tissues and vice versa. Knockdown of METTL3 additionally resulted in a reduction in HBXIP. Further investigation showed the underlying mechanism whereby HBXIP inhibited the tumour suppressor let‐7 g, which could down‐regulate METTL3. In the meanwhile, METTL3 promoted the expression of HBXIP by m6A modification. Thus, an HBXIP/let‐7 g/METTL3‐positive feedback loop forms, leading to the proliferation of breast cancer cells.91 Apart from the above, there are more encouraging findings associated with AML. It was reported that METTL3 exerted tumour promoter function in the development of AML with the methylation catalytic activity.92, 93 Knockdown of METTL3 led to a proliferation defect in AML cells, whereas overexpression of METTL3 rescued the proliferation defect, but inhibited myeloid differentiation of haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs).92, 93 Further investigations showed that the expression patterns of METTL3 and METTL14 were much more abundant in AML cell lines. And elevated m6A mediated by METTL3 played a vital role in the maintenance of the cell‐undifferentiated state in AML. Interestingly, METTL3 was identified to be recruited by CEBPZ to the transcriptional starting site of SP1, which stimulated the translation of SP1. Consequently, SP1 regulated the oncogene c‐MYC and led to the development of AML.92 Additionally, Vu et al. found that m6A mediated by METTL3 promoted the translation of c‐MYC, BCL2 and PTEN mRNAs, and the PTEN transcript may encode a negative regulator of p‐AKT which was considered to promote differentiation and inhibit self‐renewal.93

Although METTL3 was previously thought to be down‐regulated in GSCs, the concept has become controversial. A recent study has supported that METTL3 was up‐regulated in GSCs and that silencing of METTL3 inhibited cell growth by repressing POU3F2, SOX2, SALL2 and OLIG2.48 Additional investigations are supposed to be initiated to further identify the underlying mechanisms of METTL3 in GSCs.

Other studies find a new paradigm of how METTL3 affects tumour development independent of m6A modification.94 Lin et al. observed that METTL3 enhanced the translation of certain oncogenes such as EGFR, TAZ, MAPKAPK2 and DNMT3A, which bears one or more m6A peaks near the stop codon.94 However, surprisingly, METTL3 promoted translation independent of its methyltransferase activity or m6A readers, because the catalytic domain of METTL3 showed no effect in promoting translation of the above oncogenes. In addition, knockdown of YTHDF1/YTHDF2 did not influence METTL3‐mediated translation.94 These findings provide us with insight into the mechanisms of m6A modification‐related proteins.

3.2.2. METTL14

As mentioned above, METTL14 is abundant in AML cells. Weng et al. further indicated that METTL14 was highly expressed in normal HSPCs and AMLs, which was required for leukaemia stem cell self‐renewal and maintenance.95 Mechanically, METTL14 positively regulated the mRNA stability and translation of oncogene MYB and MYC, which could be negatively regulated by SPI1. However, the regulation of METTL14 on MYB and MYC is not conducted by YTHDF protein as YTHDF gene showed no consistent pattern during the process of regulation.95 Collectively, SPI1‐METTL14‐MYB/MYC axis plays a vital role in AML development. When treated with differentiation‐inducing agents such as ATRA, the level of METTL14 and m6A decreased, which proposed a novel treatment mechanism of ATRA.

3.3. Potential association of m6A with other cancers

Some m6A‐associated proteins have been found to be involved in tumour progressions before the observation and mechanism studies of m6A modification phenomenon. For example, it is known that FTO plays a role in body mass and obesity.52, 53 Besides, several studies have revealed the links between various FTO SNPs and endometrial cancer, pancreatic cancer and breast cancer.54 However, FTO was only found to promote AML and glioblastoma progression with its “eraser” role. Other FTO‐induced cancers have not been investigated so far, and additional studies need to be performed to explore the eraser role of FTO in regulating these cancers. The situation is the same for WTAP, which has been reported to have a close relationship with cancers. WTAP was overexpressed in cholangiocarcinoma, especially in metastatic cholangiocarcinoma cells inside lymph nodes or vessels. Overexpression or knockdown of WTAP significantly increased or decreased the migration and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma cells.96 And it was discovered that WTAP overexpression greatly induced metastasis‐associated genes such as MMP7 and MMP28 that degrade extracellular matrix components.96 In addition, Xi et al. confirmed that WTAP was expressed at a significantly high level in gliomas and was closely correlated with the prognosis of patients with glioblastoma.97 Interestingly, WTAP was also described as a novel oncogenic protein in AML.98 However, the m6A‐associated mechanisms of WTAP in regulating the above cancers have not been elucidated. To conclude, the above evidence strongly indicates that several m6A‐associated proteins such as FTO and WTAP are possibly involved in the progression of certain cancers, which introduces a new functional mechanism for these proteins.

4. CONCLUSIONS

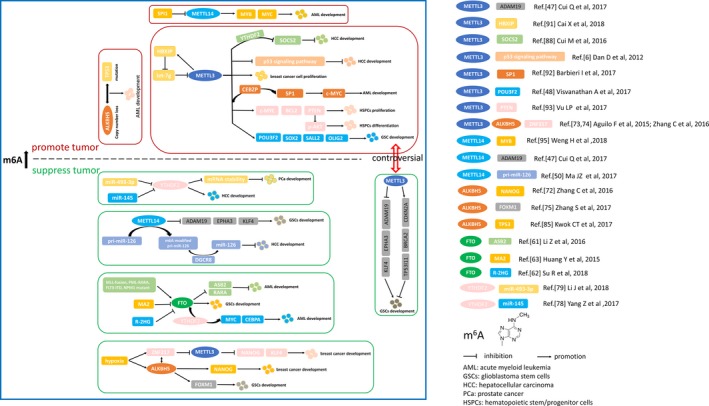

To summarize, aberrant level of m6A intimately links to human cancers, and mechanisms of the network of m6A modification and cancers are gradually being discovered, but still require further investigations. Currently, we find the dual role of m6A modification in the regulation of cancers which are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. On the one hand, increased m6A level inhibits the carcinogenesis, and on the other hand, increased m6A level promotes the tumour progressions. Because of the reversible process or because m6A is mediated by writers, erasers and readers, the dysregulations of these proteins may trigger or be involved in the tumour progressions. In terms of mechanisms, m6A modification, as a critical post‐transcriptional regulation, is demonstrated to dynamically regulate RNA biology and may be a vital tumour promoter or suppressor involved in tumour progressions. The expression pattern of the same m6A‐associated protein and its target mRNAs may differ in multiple cancers, which represents the significant tumour specificity. Previously determined m6A‐associated proteins involved in cancers may need additional investigations to explore the new regulatory mechanisms according to the m6A way. Thus, the function of m6A may be broader than the existing paradigm and may provide profound insights into tumorigenesis and cancer development. However, details are still lacking and a better understanding of the basic mechanism is required. In addition, corresponding proteins that dynamically regulate m6A methylation require further exploration.

Table 1.

The dual role of m6A modification in human cancers

| Molecule | Cancer | Role in cancer | Biological function | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m6A modification inhibits the tumour progression | ||||

| METTL3 | GBM (glioblastoma) | Suppressor gene | Suppresses GSC (glioblastoma stem cells) growth and self‐renewal | Down‐regulates ADAM19, EPHA3 and KLF4; Up‐regulates CDKN2A, BRCA2 and TP53I11 |

| METTL14 | GBM | Suppressor gene | Suppresses GSC growth and self‐renewal | Down‐regulates ADAM19, EPHA3 and KLF4 |

| METTL14 | HCC | Suppressor gene | Suppresses HCC metastasis | Promotes pri‐MIR‐126 processing |

| FTO | AML | Oncogene | Promotes AML carcinogenesis | Inhibits ASB2/RARA axis |

| FTO | AML | Oncogene | Promotes AML carcinogenesis | Enhances MYC and CEBPA mRNA stability |

| ALKBH5 | Breast cancer | Oncogene | Promotes breast cancer initiation | Enhances NANOG and KLF4 mRNA stability |

| ALKBH5 | GBM | Oncogene | Promotes GBM proliferation and self‐renewal | Promotes FOXM1 expression |

| YTHDF2 | Prostate cancer | Oncogene | Promotes prostate cancer growth and migration | Promotes m6A‐containing mRNA degradation |

| m6A modification promotes the tumour progression | ||||

| METTL3 | AML | Oncogene | Promotes proliferation; Inhibits differentiation | Promotes MYC, BCL2 and PTEN translation |

| METTL3 | Breast cancer | Oncogene | Promotes breast cancer cells proliferation | Promotes HBXIP translation |

| METTL3 | HCC | Oncogene | Promotes HCC growth | Promotes SOCS2 degradation |

| METTL3 | GBM | Oncogene | Promotes GSCs growth and self‐renewal | Up‐regulates POU3F2, SOX2, SALL2 and OLIG2 |

| METTL14 | AML | Oncogene | Promotes AML cells self‐renewal and maintenance | Up‐regulates MYB and MYC |

Figure 2.

Dual role of m6A modification in human cancers. Aberrant expression of m6A modification induced by down‐regulation or up‐regulation of methyltransferases, demethylases or readers promotes or suppresses tumour development. See references for more details.

As an RNA modification, m6A opens avenues for correlating epigenetics with diseases, especially cancer, which proposes a new mechanism in cancer regulations. In terms of the translation into clinical medicine, it will be of great importance to investigate whether competitive antagonists of those proteins can act as potential anticancer agents.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

LH, JL and XW equally contributed to the collection of data, preparation of figures and drafting individual sections of the manuscript; YY, HX and HY contributed to the collection of data and writing individual sections of the manuscript; XZ and LX revised and expanded the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81772744) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M632489). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

He L, Li J, Wang X, et al. The dual role of N6‐methyladenosine modification of RNAs is involved in human cancers. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:4630–4639. 10.1111/jcmm.13804

Liujia He, Jiangfeng Li, Xiao Wang these authors have contributed equally to this work.

Main topics: The discovery of m6A and its function; the dual role of m6A modification in human cancers.

Contributor Information

Xiangyi Zheng, Email: zheng_xy@zju.edu.cn.

Liping Xie, Email: xielp@zju.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature. 2007;447:396‐398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Breiling A, Lyko F. Epigenetic regulatory functions of DNA modifications: 5‐methylcytosine and beyond. Epigenetics & Chromatin. 2015;8:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang LL, Wu JX. DNA methylation: an epigenetic mechanism for tumorigenesis. Hereditas. 2006;28:880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, et al. N6‐methyladenosine‐dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deng X, Chen K, Luo GZ, et al. Widespread occurrence of N6‐methyladenosine in bacterial mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6557‐6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dan D, Moshitch‐Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A‐seq. Nature. 2012;485:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wei W, Ji X, Guo X, Ji S. Regulatory Role of N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) methylation in RNA processing and human diseases. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:2534‐2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Batista PJ, The RNA. Modification N(6)‐methyladenosine and Its Implications in Human Disease. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics. 2017;15:154‐163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maity A, Das B. N6‐methyladenosine modification in mRNA: machinery, function and implications for health and diseases. FEBS J. 2016;283:1607‐1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, et al. N6‐methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity‐associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:885‐887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3971‐3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49:18‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fu Y, Dominissini D, Rechavi G, He C. Gene expression regulation mediated through reversible m6A RNA methylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:293‐306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yue Y, Liu J, He C. RNA N6‐methyladenosine methylation in post‐transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1343‐1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ougland R, Zhang CM, Liiv A, et al. AlkB restores the biological function of mRNA and tRNA inactivated by chemical methylation. Mol Cell. 2004;16:107‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ueda Y, Ooshio I, Fusamae Y, et al. AlkB homolog 3‐mediated tRNA demethylation promotes protein synthesis in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tuck MT. Partial purification of a 6‐methyladenine mRNA methyltransferase which modifies internal adenine residues. Biochem J. 1992;288(Pt 1):233‐240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, et al. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet‐binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6‐adenosine)‐methyltransferase. RNA. 1997;3:1233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, et al. A METTL3‐METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6‐adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:93‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6‐methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24:177‐189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, et al. Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5′ Sites. Cell Rep. 2014;8:284‐296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yue Y, Liu J, Cui X, et al. VIRMA mediates preferential m6A mRNA methylation in 3′UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov. 2018;4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wen J, Lv R, Ma H, et al. Zc3 h13 regulates nuclear RNA m6A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self‐renewal. Mol Cell. 2018;69:1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patil DP, Chen CK, Pickering BF, et al. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST‐mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 2016;537:369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Hackert P, et al. Human METTL16 is a N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) methyltransferase that targets pre‐mRNAs and various non‐coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, et al. The U6 snRNA m 6 A Methyltransferase METTL16 Regulates SAM Synthetase Intron Retention. Cell. 2017;169:824‐835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree I, et al. N6‐methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161:1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu C, Wang X, Liu K, et al. Structural basis for selective binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:927‐929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Roundtree IA, He C. Nuclear m(6)A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Trends Genet. 2016;32:320‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6‐methyladenosine‐modified RNA. Cell Res. 2017;27:315‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu PJ, Zhu Y, Ma H, et al. Ythdc2 is an N6‐methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 2017;27:1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alarcon CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, et al. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m(6)A‐Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell. 2015;162:1299‐1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, et al. N6‐methyladenosine‐dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA‐protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518:560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bodi Z, Fray RG. Detection and quantification of N (6)‐Methyladenosine in messenger RNA by TLC. Methods Mol Biol 2017;1562:79‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA Methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near Stop Codons. Cell. 2012;149:1635‐1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dominissini D, Moshitchmoshkovitz S, Salmondivon M, et al. Transcriptome‐wide mapping of N(6)‐methyladenosine by m(6)A‐seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:176‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen K, Lu Z, Wang X, et al. High‐resolution N(6) ‐methyladenosine (m(6) A) map using photo‐crosslinking‐assisted m(6) A sequencing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:1587‐1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu N, Pan T. Probing RNA modification status at single‐nucleotide resolution in total RNA. Methods Enzymol. 2015;560:149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grozhik AV, Linder B, Olareringeorge AO, Jaffrey SR. Mapping m6A at individual‐nucleotide resolution using crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP). Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1562:55‐78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fustin JM, Doi M, Yamaguchi Y, et al. RNA‐methylation‐dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell 2013;155:793‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lin S, Gregory RI. Methyltransferases modulate RNA stability in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:129‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Geula S, Moshitch‐Moshkovitz S, Dominissini D, et al. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347:1002‐1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Benhaim MS, Moshitchmoshkovitz S, Rechavi G. FTO: linking m6A demethylation to adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2015;25:3‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shen F, Huang W, Huang JT, et al. Decreased N(6)‐methyladenosine in peripheral blood RNA from Diabetic Patients Is Associated with FTO Expression Rather than ALKBH5. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:148‐154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang X, Li Z, Kong B, et al. Reduced m6A mRNA methylation is correlated with the progression of human cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:98918‐98930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sordillo PP, Sordillo LA, Helson L. The kynurenine pathway: a primary resistance mechanism in patients with glioblastoma. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:2159‐2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cui Q, Shi H, Ye P, et al. m6A RNA Methylation Regulates the Self‐Renewal and Tumorigenesis of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2017;18:2622‐2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Visvanathan A, Patil V, Arora A, et al. Essential role of METTL3‐mediated m6A modification in glioma stem‐like cells maintenance and radioresistance. Oncogene. 2017;37:522‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang S, Sun C, Li J, et al. Roles of RNA methylation by means of N6‐methyladenosine (m6A) in human cancers. Cancer Lett. 2017;408:112‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ma JZ, Yang F, Zhou CC, et al. METTL14 suppresses the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating N(6) ‐methyladenosine‐dependent primary MicroRNA processing. Hepatology. 2017;65:529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tavazoie SF, Alarcn C, Oskarsson T, et al. Endogenous human microRNAs that suppress breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2008;451:147‐152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316:889‐894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dina C, Meyre D, Gallina S, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:724‐726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kang Y, Liu F, Liu Y. Is FTO gene variant related to cancer risk independently of adiposity? An updated meta‐analysis of 129,467 cases and 290,633 controls. Oncotarget. 2017;8:50987‐50996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Machiela MJ, Lindstrom S, Allen NE, et al. Association of type 2 diabetes susceptibility variants with advanced prostate cancer risk in the Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:1121‐1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Delahanty RJ, Beeghly‐Fadiel A, Xiang YB, et al. Association of obesity‐related genetic variants with endometrial cancer risk: a report from the shanghai endometrial cancer genetics study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Long J, Zhang B, Signorello LB, et al. Evaluating genome‐wide association study‐identified breast cancer risk variants in African‐American women. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tarabra E, Actis GC, Fadda M, et al. The obesity gene and colorectal cancer risk: a population study in Northern Italy. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:65‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tan A, Dang Y, Chen G, Mo Z. Overexpression of the fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) in breast cancer and its clinical implications. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13405‐13410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kaklamani V, Yi N, Sadim M, et al. The role of the fat mass and obesity associated gene (FTO) in breast cancer risk. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li Z, Weng H, Su R, et al. FTO Plays an oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a N 6 ‐Methyladenosine RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell. 2016;31:127‐141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Su R, Dong L, Li C, et al. R‐2HG exhibits anti‐tumor activity by targeting FTO/m(6)A/MYC/CEBPA signaling. Cell. 2018;172(90–105):e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Huang Y, Yan J, Li Q, et al. Meclofenamic acid selectively inhibits FTO demethylation of m6A over ALKBH5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:373‐384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Thalhammer A, Bencokova Z, Poole R, et al. Human AlkB Homologue 5 Is a Nuclear 2‐Oxoglutarate Dependent Oxygenase and a Direct Target of Hypoxia‐Inducible Factor 1α (HIF‐1α). PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vaupel P, Mayer A, Höckel M. Tumor hypoxia and malignant progression. Methods Enzymol. 2004;381:335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vaupel P, Höckel M, Mayer A. Detection and characterization of tumor hypoxia using pO2 histography. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Harris AL. Hypoxia–a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gong J, Maia MC, Dizman N, et al. Metastasis in renal cell carcinoma: biology and implications for therapy. Asian J Urol. 2016;3:286‐292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Semenza GL. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment: a driving force for breast cancer progression. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Iv Santaliz‐Ruiz LE, Xie X, Old M, et al. Emerging role of nanog in tumorigenesis and cancer stem cells. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2741‐2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fang Y, Li J, Chen H, et al. Kruppel‐like factor 4 (KLF4) is required for maintenance of breast cancer stem cells and for cell migration and invasion. Oncogene. 2011;30:2161‐2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang C, Samanta D, Lu H, et al. Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF‐dependent and ALKBH5‐mediated m6A‐demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Aguilo F, Zhang F, Sancho A, et al. Coordination of m 6 A mRNA methylation and gene transcription by ZFP217 regulates pluripotency and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:689‐704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhang C, Zhi WI, Lu H, et al. Hypoxia‐inducible factors regulate pluripotency factor expression by ZNF217‐ and ALKBH5‐mediated modulation of RNA methylation in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:64527‐64542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, et al. m(6)A Demethylase ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem‐like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang N, Wei P, Gong A, et al. FoxM1 Promotes β‐Catenin Nuclear Localization and Controls Wnt Target‐Gene Expression and Glioma Tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:427‐442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kim SH, Joshi K, Ezhilarasan R, et al. EZH2 Protects Glioma Stem Cells from Radiation‐Induced Cell Death in a MELK/FOXM1‐Dependent Manner. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4:226‐238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yang Z, Li J, Feng G, et al. MicroRNA‐145 Modulates N6‐Methyladenosine Levels by Targeting the 3′‐Untranslated mRNA Region of the N6‐Methyladenosine Binding YTH Domain Family 2 Protein. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:3614‐3623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Li J, Meng S, Xu M, et al. Downregulation of N(6)‐methyladenosine binding YTHDF2 protein mediated by miR‐493‐3p suppresses prostate cancer by elevating N(6)‐methyladenosine levels. Oncotarget. 2018;9:3752‐3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pakneshan P, Szyf M, Farias‐Eisner R, Rabbani SA. Reversal of the hypomethylation status of urokinase (uPA) promoter blocks breast cancer growth and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31735‐31744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pascale RM, Simile MM, De Miglio MR, Feo F. Chemoprevention of hepatocarcinogenesis: S‐adenosyl‐L‐methionine. Alcohol 2002;27:193‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lu SC, Ramani K, Ou X, et al. S‐adenosylmethionine in the chemoprevention and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in a rat model. Hepatology. 2009;50:462‐471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Guruswamy S, Swamy MV, Choi CI, et al. S‐adenosyl L‐methionine inhibits azoxymethane‐induced colonic aberrant crypt foci in F344 rats and suppresses human colon cancer Caco‐2 cell growth in 3D culture. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:25‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhao Y, Li JS, Guo MZ, et al. Inhibitory effect of S‐adenosylmethionine on the growth of human gastric cancer cells in vivo and in vitro. Chin J cancer. 2010;29:752‐760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kwok CT, Marshall AD, Rasko JEJ, Wong JJL. Genetic alterations of m 6 A regulators predict poorer survival in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Huang W, Qi CB, Lv SW, et al. Determination of DNA and RNA Methylation in Circulating Tumor Cells by Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2016;88:1378‐1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chen M, Wei L, Law CT, et al. RNA N6‐methyladenosine methyltransferase METTL3 promotes liver cancer progression through YTHDF2 dependent post‐transcriptional silencing of SOCS2. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2017. 10.1002/hep.29683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cui M, Ji S, Hou J, et al. The suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2) inhibits tumor metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2016;10:1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Zhao Y, Li H, Zhang Y, et al. Oncoprotein HBXIP modulates abnormal lipid metabolism and growth of breast cancer cells by activating the LXRs/SREBP‐1c/FAS signaling cascade. Can Res. 2016;76:4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Li Y, Wang Z, Shi H, et al. HBXIP and LSD1 scaffolded by lncRNA hotair mediate transcriptional activation by c‐Myc. Can Res. 2016;76:293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Cai X, Wang X, Cao C, et al. HBXIP‐elevated methyltransferase METTL3 promotes the progression of breast cancer via inhibiting tumor suppressor let‐7 g. Cancer Lett. 2018;415:11‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Barbieri I, Tzelepis K, Pandolfini L, et al. Promoter‐bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m(6)A‐dependent translation control. Nature. 2017;552:126‐131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Vu LP, Pickering BF, Cheng Y, et al. The N6‐methyladenosine (m6A)‐forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat Med. 2017;23:1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lin S, Choe J, Du P, et al. The m(6)A Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Translation in Human Cancer Cells. Mol Cell. 2016;62:335‐345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Weng H, Huang H, Wu H, et al. METTL14 inhibits hematopoietic stem/progenitor differentiation and promotes leukemogenesis via mRNA m(6)A modification. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(191–205):e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Jo HJ, Shim HE, Han ME, et al. WTAP regulates migration and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma cells. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1271‐1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Xi Z, Xue Y, Zheng J, et al. WTAP expression predicts poor prognosis in malignant glioma patients. J Mol Neurosci 2016;60:1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bansal H, Yihua Q, Iyer SP, et al. WTAP is a novel oncogenic protein in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28:1171‐1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]