Identification of Shigella spp., Escherichia coli, and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) is challenging because of their close relatedness. Distinction is vital, as infections with Shigella spp.

KEYWORDS: EIEC, Escherichia coli, Shigella, whole-genome sequencing, enteroinvasive E. coli, identification, molecular methods, phenotypic methods

ABSTRACT

Identification of Shigella spp., Escherichia coli, and enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) is challenging because of their close relatedness. Distinction is vital, as infections with Shigella spp. are under surveillance of health authorities, in contrast to EIEC infections. In this study, a culture-dependent identification algorithm and a molecular identification algorithm were evaluated. Discrepancies between the two algorithms and original identification were assessed using whole-genome sequencing (WGS). After discrepancy analysis with the molecular algorithm, 100% of the evaluated isolates were identified in concordance with the original identification. However, the resolution for certain serotypes was lower than that of previously described methods and lower than that of the culture-dependent algorithm. Although the resolution of the culture-dependent algorithm is high, 100% of noninvasive E. coli, Shigella sonnei, and Shigella dysenteriae, 93% of Shigella boydii and EIEC, and 85% of Shigella flexneri isolates were identified in concordance with the original identification. Discrepancy analysis using WGS was able to confirm one of the used algorithms in four discrepant results. However, it failed to clarify three other discrepant results, as it added yet another identification. Both proposed algorithms performed well for the identification of Shigella spp. and EIEC isolates and are applicable in low-resource settings, in contrast to previously described methods that require WGS for daily diagnostics. Evaluation of the algorithms showed that both algorithms are capable of identifying Shigella species and EIEC isolates. The molecular algorithm is more applicable in clinical diagnostics for fast and accurate screening, while the culture-dependent algorithm is more suitable for reference laboratories to identify Shigella spp. and EIEC up to the serotype level.

INTRODUCTION

In 1898, Kiyoshi Shiga first described Shigella dysenteriae as the etiologic agent of dysentery (1). Nowadays, the genus Shigella comprises four species based on antigenic properties, Shigella dysenteriae, Shigella flexneri, Shigella boydii, and Shigella sonnei. All species cause symptoms varying from mild diarrheal episodes to dysentery (2).

The relatedness of Shigella spp. with Escherichia coli has always been recognized (3–6). In addition, in the 1940s, an E. coli pathotype was described that has the same invasive mechanism as Shigella species. This pathotype was named enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC) and is more related to Shigella spp. than noninvasive E. coli (7). EIEC and Shigella spp. possess the same virulence genes, which are located on the chromosome and carried by a large invasion plasmid (pINV) (8).

The close relatedness of Shigella spp. and E. coli challenges identification if they are encountered in laboratories. Nowadays, an initial molecular screening of fecal samples is often used for the detection of Shigella spp., in which the ipaH gene is a frequently used target (9–11). This is a multicopy virulence gene present on both the chromosome and pINV of Shigella spp. and EIEC strains and not present in commensal or other pathotypes of E. coli (12). Consequently, the ipaH gene can distinguish Shigella spp. from all pathotypes of E. coli, except for EIEC. After this initial screening, most laboratories perform culture to select Shigella and EIEC isolates for differentiation and antibiotic resistance profiling. Species identification of a selected isolate is traditionally based on phenotypical key characteristics, including motility, lysine decarboxylase, and the ability to produce both gas and indole, which are negative for Shigella spp. and usually positive for E. coli (13, 14). Unfortunately, EIEC isolates can either be positive or negative for these features (15).

In many countries, it is obligatory to notify health authorities if a laboratory confirms a case of shigellosis. In contrast, infections with EIEC are not notifiable. Therefore, a diagnostic algorithm able to distinguish Shigella spp. from E. coli, including EIEC, is required.

In the last decade, multiple molecular identification methods for Shigella spp. and E. coli, including EIEC, were reported (5, 6, 8, 16–19). One of these methods is based on the presence of the uidA and lacY genes (16, 19). However, this method appeared to be not as accurate as expected (6). Alternatively, a few research groups used whole-genome sequencing (WGS) for the distinction of Shigella spp. from E. coli (5, 6, 17, 18). Although some methods based on WGS analysis showed effectiveness, the described identification markers are phylogenetic clade specific rather than species specific (5, 6, 8). In another study, identification markers were identified by a BLAST search of coding regions of genomes of the different species (17). Consequently, these identification markers were species specific instead of clade specific; however, they were validated using only one EIEC isolate (17). Pettengill et al. (6) used a k-mer-based approach to distinguish between Shigella spp. and E. coli; however, some EIEC isolates were incorrectly identified as Shigella spp. by this approach (18). In conclusion, differentiation of Shigella spp. and E. coli, and of Shigella and EIEC in particular, is a challenge.

Despite it being proven before that Shigella spp. and EIEC are related and that EIEC is a diverse pathotype (5, 6, 8, 18), distinction is necessary for infectious disease control measures, as in many countries, shigellosis is a notifiable disease, in contrast to infections with EIEC. In this study, a culture-dependent identification algorithm was developed, based on previously described molecular, phenotypical, and serological features of Shigella spp. and EIEC. In addition, this algorithm was compared to a recently developed molecular identification algorithm (R. F. de Boer, M. J. C. van den Beld, W. de Boer, M. C. Scholts, K. W. van Huisstede-Vlaanderen, A. Ott, and A. M. D. Kooistra-Smid, unpublished data) for the identification of Shigella spp., E. coli, and EIEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates and original identification.

The selection of isolates was based on Shigella serotype or E. coli O type and is listed in Table 1. For selection, the original identification was a guide. This original identification was established with different methods at different institutes spanning the last 50 to 60 years. Most documentation about the methods used is lost. Therefore, except for the purchased isolates, the original identification cannot be considered the gold standard, and only concordance or discordance with the results obtained by the here-described algorithms can be examined.

TABLE 1.

Original identification and original collection of the isolates used in this study

| Genus and species | Strain | Serotypea | Original collectionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. dysenteriae | CIP 57.28T | 1 | CIP |

| A1 | 1 | CDC → Cib | |

| A2 | 2 | CDC → Cib | |

| A3 | 3 | CDC → Cib | |

| A4 | 4 | CDC → Cib | |

| A5 | 5 | CDC → Cib | |

| A6 | 6 | CDC → Cib | |

| A7 | 7 | CDC → Cib | |

| 505/58 | 8 | Cib | |

| A9 | 9 | CDC → Cib | |

| A10 | 10 | CDC → Cib | |

| BD92-00426 | 12 | Cib | |

| S. flexneri | CIP 82.48T | 2a | CIP |

| 9950c | 1a | SSI | |

| 9722c | 1b | SSI | |

| 12698c | 2b | SSI | |

| Zc | 3a | SSI | |

| 9989c | 3a | SSI | |

| BD10-00109 | 3b | Cib | |

| 8296c | 4a | SSI | |

| 9726c | 4b | SSI | |

| 8523c | 5a | SSI | |

| 8524c | 5b | SSI | |

| 9729c | 6 | SSI | |

| 9951c | Y | SSI | |

| S. boydii | CIP 82.50T | 2 | CIP |

| 9327c | 1 | SSI | |

| 9850c | 3 | SSI | |

| 9770c | 4 | SSI | |

| 9733c | 5 | SSI | |

| 9771c | 6 | SSI | |

| 9734c | 7 | SSI | |

| 9328c | 8 | SSI | |

| 9355c | 9 | SSI | |

| 9357c | 10 | SSI | |

| 9359c | 11 | SSI | |

| 9772c | 12 | SSI | |

| 8592c | 14 | SSI | |

| 10024c | 15 | SSI | |

| S. sonnei | CIP 82.49T | ND | CIP |

| 9774c | Phase I | SSI | |

| BD13-00218 | Phase I & II | Cib | |

| 8219c | Phase II | SSI | |

| Provisional Shigella | BD09-00375 | O159 | Cib |

| E. coli (EIEC) | CCUG 11335 | O28 | CCUG |

| T72351c | O28 | SSI | |

| W71750c | O28 | SSI | |

| BD12-00018 | O29 | Cib | |

| F54157c | O64 | SSI | |

| F54197c | O64 | SSI | |

| BD11-00138 | O102 | Cib | |

| DSM 9027 | O112ac | DSMZ | |

| BD11-00028 | O121 | Cib | |

| F20871c | O121 | SSI | |

| EW227 | O124 | CDC → Cib | |

| BD13-00007 | O124 | Cib | |

| b7(D2192)c | O124 | SSI | |

| 1111-55 | O136 | CDC → Cib | |

| No2 VIR (fr1292)c | O143 | SSI | |

| N02135 AVIR (fr1294)c | O143 | SSI | |

| DSM 9028 | O143 | DSMZ | |

| M26020c | O144 | SSI | |

| 1624-56 | O144 | CDC → Cib | |

| BD09-00443 | O152 | Cib | |

| 1184-68 | O152 | CDC → Cib | |

| BD13-00213 | O159 | Cib | |

| BD09-00375 | O159 | Cib | |

| 145/46 | O164 | CDC → Cib | |

| BH 2232-5c | O172 | SSI | |

| L119-10B | O173 | SSI → Cib | |

| T20103c | O173 | SSI | |

| H57237c | O+ | SSI | |

| H19610c | O+ | SSI | |

| BD13-00037 | O untypeable | Cib | |

| E. coli (noninvasive) | DSM 9026 | O29 | DSMZ |

| Coli-Pecs | O135 | CDC → Cib | |

| E10702 | O167 | CDC → Cib |

Shigella serotype in case of Shigella spp. or E. coli O type in case of E. coli or provisional Shigella. ND, not determined.

CIP, Collection de l'Institut Pasteur, Paris, France; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA; Cib, Centre for Infectious Disease Control, Bilthoven, The Netherlands; CDC/SSI → Cib, historical isolates donated to Cib by the CDC or SSI, respectively, for antiserum preparation and validation from 1950s to 1980s; SSI, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark; CCUG, Culture Collection, University of Göteborg, Sweden; DSMZ, Leibniz-Institut DSMZ-Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany.

Provided by F. Scheutz, SSI.

Culture-dependent algorithm.

The culture-dependent algorithm was designed to facilitate identification and serotyping of Shigella spp. or EIEC from pure cultures up to the serotype level. It was based on the positivity of the ipaH gene and then subsequent profiling of earlier described phenotypical and serological features.

The isolates were cultured overnight at 37°C on Columbia sheep blood agar (CSA; bioTRADING, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands). Lysates were prepared by boiling strains in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]; Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) for 30 min. A PCR to detect the ipaH gene was performed using a Biometra TProfessional standard gradient thermocycler (Westburg, Leusden, The Netherlands), with the following program: 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles consisting of 95°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and an elongation for 7 min at 72°C. As a mastermix, illustra PuReTaq Ready-To-Go PCR beads (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) were used, supplemented with the following primers designed for amplification of a conservative part of the ipaH gene present in all different ipaH alleles (20): forward primer, 5′-TGG AAA AAC TCA GTG CCT C-3′; and reverse primer, 5′-CCA GTC CGT AAA TTC ATT CTC-3′. As an internal control for presence of bacterial DNA, a conservative part of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with the following primers: forward primer, 5′-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG YTC AG-3′; and reverse primer, 5′-CTT TAC GCC CAR TRA WTC CG-3′. All primers were used in a final concentration of 0.2 pmol/μl.

The ipaH-positive isolates were subjected to the following phenotypic tests: oxidase, catalase, motility at 22°C and 37°C, growth on MacConkey agar and Salmonella Shigella agar (SS agar), gas from d-glucose, ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), indole, esculin hydrolysis, ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG), and fermentation of d-glucose, lactose, d-sucrose, d-xylose, d-mannitol, dulcitol, salicin, d-raffinose, and d-glycerol in Andrade peptone water (21), lysine decarboxylase (LDC [22]), and arginine dihydrolase (ADH [23]).

Next to the phenotypical tests, classical Shigella serotyping was performed with all available Shigella antisera obtained from Denka Seiken Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), complemented with S. flexneri MASF IV-1, MASF IV-2, MASF 1c, and MASF B from Reagensia AB (Solna, Sweden). If slide agglutination was negative for all polyvalent antisera or an inconclusive serotype was obtained, a suspension of the isolate was boiled for 1 h, after which slide agglutination was performed again.

Classical E. coli O serotyping was manually performed with antisera for E. coli O1 until O187, prepared as previously described (24, 25) or purchased from Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark). O-antigen suspensions were prepared by boiling an overnight broth culture for 1 h to inactivate the K antigen. These prepared antigens, diluted (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.44) with formalinized (0.5%) phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), were stained with gentian violet (0.005%) and tested against the 187 O antisera in microtiter plate agglutination tests. After overnight incubation at 37°C, plates were examined against a light background, and positive reactions were titrated. O-type reactions with titers of ≥2,500, and reactions with titers until two steps lower than the reaction of the homologous standard were considered positive.

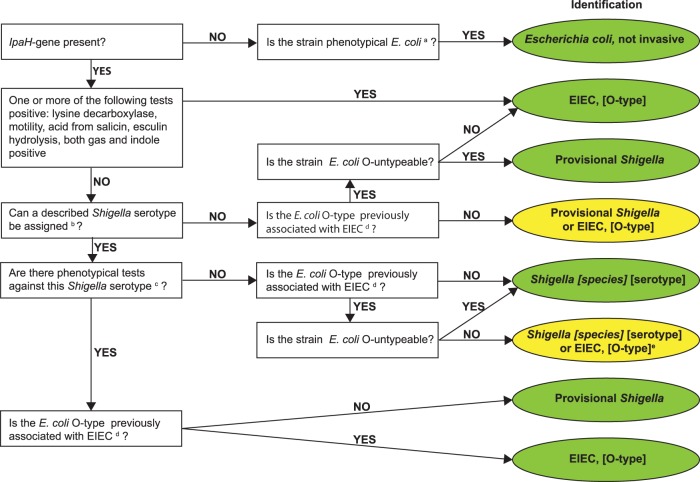

With the results of the above-described molecular, biochemical, and serological tests, an identification algorithm was applied as shown in Fig. 1, based on a previously described key (Fig. 2 in reference 26). A result was considered inconclusive if a distinction between a Shigella species and EIEC could not be made and the serotypes are not described as related.

FIG 1.

Culture-dependent algorithm. Green, definitive identification; yellow, inconclusive identification; a, Strockbine et al. (32); b, manufacturer's protocol for Shigella antisera set 1, as per Denka Seiken, Sun et al. (41, 43), and Carlin et al. (44); c, Bopp et al. (13); d, O28ac, O29, O42, O96, O112ac, O115, O121, O124, O135, O136, O143, O144, O152, O159, O164, O167, O173, and O untypeable; e, if Shigella serotype has a known relation to E. coli O type, identification is Shigella [species] [serotype]; see Ewing (31), Cheasty and Rowe (45), Liu et al. (39), and Perepelov et al. (42).

Molecular algorithm.

The molecular algorithm was designed to screen fecal samples for the presence of Shigella spp./EIEC quickly and accurately. However, in this study, only pure cultures were examined; thus, only the molecular part of the algorithm that follows bacterial isolation was applied (de Boer et al., unpublished data).

Briefly, lysates were prepared as described above. A real-time PCR to target the ipaH and the wzx genes of S. sonnei phase I, S. flexneri serotype 1-5, S. flexneri 6, and S. dysenteriae serotype 1 was performed on a ABI 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk aan den IJssel, The Netherlands), as described previously (11). Each 25-μl reaction mixture consisted of 5 μl template DNA, 1× Fast Advanced TaqMan Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), and 2.5 μg bovine serum albumin (Roche Diagnostics Netherlands B.V., Almere, The Netherlands). The primers and probes used for detection were designed based on the sequence of wzx genes, as described previously (27, 28). Reactions were performed under the following conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 s, and 60°C for 32 s. With the result of the ipaH gene PCR, a distinction between Shigella/EIEC and noninvasive E. coli was made. Positivity of a wzx gene, in an expected ratio with a threshold cycle (CT) value of the ipaH gene according to copy number (20), leads to the corresponding serotype. If the ipaH gene had a CT value below 35 but all tested wzx genes were negative, the identification is inconclusive and was interpreted as EIEC, S. boydii, S. sonnei phase II, or S. dysenteriae serotype 2-15.

Discrepancy analysis using whole-genome sequencing.

WGS analysis was performed on seven isolates to solve discrepancies between the here-proposed algorithms and original identification (Tables 2 and 3). Isolates were cultured overnight at 37°C on CSA. For each isolate, an equivalent to 5 μl of colonies was suspended in 300 μl MicroBead solution, and DNA was extracted with the UltraClean microbial DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The DNA library was prepared with the Nextera XT version 2 index kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Subsequently, the library was sequenced on a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, Inc.), using a MiSeq reagent kit version 3 generating 300-bp paired-end reads.

TABLE 2.

Results of identification with culture-dependent and molecular algorithm compared to original identificationa

| Original identification (n) | Culture-dependent algorithm |

Molecular algorithm |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant |

Inconclusive |

Discordant |

Concordant |

Inconclusive |

Discordant |

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| S. dysenteriae (12) | 11 (12) | 92 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 8 (0) | 2 | 17 | 10 | 83 | 0 | 0 |

| S. flexneri (13) | 8 | 62 | 3 | 23 | 2 | 15 | 13 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| S. boydii (14) | 13 | 93 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| S. sonnei (4) | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 50 | 2 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| EIEC (30) | 26 (27) | 87 (90) | 1 | 3 | 3 (2) | 10 (7) | 0 (1) | 0 (3) | 29 | 97 | 1 (0) | 3 (0) |

| E. coli, noninvasive (3) | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Concordant or discordant refers to comparison with the original identification (Table 1). For inconclusive identification, the original identification is in concordance with one of the results. Values in parentheses are the results after discrepancy analysis.

TABLE 3.

Discrepancy analysis of isolates with discordant results based on the culture dependent algorithm

| Isolate | Original identification | Results of culture-dependent algorithm and motivation | Results of molecular algorithm | Predicted E. coli serotypea | Predicted Shigella O type | Presence/absence of genes for deviant resultsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 505/58 | S. dysenteriae serotype 8 | EIEC, O untypeable; serologically S. dysenteriae 8, negative indole production against | S. dysenteriae non-O1/S. boydii/S. sonnei phase II/EIEC | O38: H26 | S. dysenteriae serotype 8 | tnaCAB cluster absent |

| 12698 | S. flexneri serotype 2b | EIEC, O untypeable; serological S. flexneri 2b, positive d-mannitol fermentation against | S. flexneri | O13:H14 | S. flexneri 2bc | mtlA, mtlD, and mtlR genes (mannitol operon) present |

| Z | S. flexneri serotype 3a | EIEC, O135; S. flexneri polyvalent positive, no conclusive serotype; antigenic formula B;6 | S. flexneri | O13/O135:H14 | S. flexneri 1cd | NA |

| 9355 | S. boydii serotype 9 | Provisional Shigella; serologically S. boydii 9, negative indole production against | S. dysenteriae non-O1/S. boydii/S. sonnei phase II/EIEC | No O-type genes, H14 | S. boydii serotype 9 | tnaCAB cluster present, tnaC and rrlB genes contain features essential for induction of tnaCAB cluster |

| F54157 | EIEC, O64 | S. sonnei, phase II; serologically and biochemically fit by repeat | S. dysenteriae non-O1/S. boydii/S. sonnei phase II/EIEC | O149:H45 | S. boydii, serotype 1; no S. sonnei, S. flexneri, or S. dysenteriae O-antigen genes present | NA |

| F54197 | EIEC, O64 | S. sonnei, phase II; serologically and biochemically fit by repeat | S. dysenteriae non-O1/S. boydii/S. sonnei phase II/EIEC | O149:H45 | S. boydii, serotype 1; no S. sonnei, S. flexneri or S. dysenteriae O-antigen genes present | NA |

| H57237 | EIEC, O+ | S. flexneri, serotype Yv | S. flexneri | O13:H14 | S. flexneri Yve | NA |

Using SerotypeFinder, Center for Genomic Epidemiology.

NA, not applicable.

wzx1-5, gtrII, and gtrX present.

wzx1-5, gtrI, gtrIc, and oac present.

wzx1-5 and lpt-O present.

Quality control, quality trimming, and de novo assembly was performed using CLC Genomics Workbench, version 9.1.1 (Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark). A quality limit of 0.01 was used in trimming, and a word size of 29 and a minimum contig length of 1,000 bp were used in de novo assembly. Other parameters were set as default.

E. coli O types were predicted using SerotypeFinder (Center for Genomic Epidemiology, Lyngby, Denmark). To predict the serotype of Shigella, trimmed reads of the isolates were mapped against references of the S. flexneri O-antigen genes (29) and the O-antigen gene clusters of S. dysenteriae, S. boydii, and S. sonnei (28). To our knowledge, S. dysenteriae serotypes 14 and 15 are rare, and the sequence of their O antigens is not known; therefore, these serotypes were not evaluated in silico. The tnaCAB gene cluster and rrlB gene were used as references for indole production from tryptophan and the mtlA, mtlD, and mtlR genes as references for the fermentation of d-mannitol. All genes and gene clusters were retrieved from NCBI (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). If reads mapped with one or more mutations, the functionality of the encoded proteins was assessed using ExPASy (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics [SIB] [30]) and BLASTp (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA).

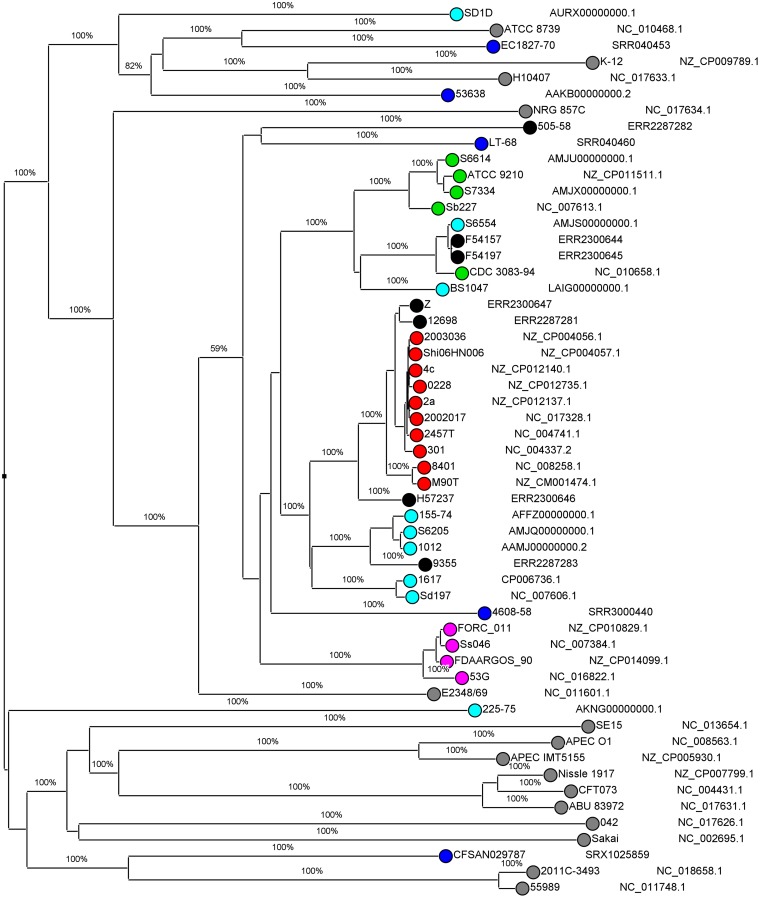

The de novo assemblies were imported in SeqSphere+ version 3.5.1 (Ridom GmbH, Münster, Germany), including reference genomes retrieved from NCBI, to assess the homologies of the discrepant strains with the references. A comparison of the sequences was made using the E. coli core-genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) genotyping scheme, which is based on the EnteroBase Escherichia/Shigella cgMLST version 1 scheme (https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/species/index/ecoli). The resulting comparison table was imported in BioNumerics, version 7.6.3 (Applied Maths, NV), and a neighbor joining tree was inferred using 200× bootstrap resampling. The tree with the highest resampling support was calculated. The accession numbers of all sequences are depicted in Fig. 2.

FIG 2.

Neighbor-joining tree for core-genome MLST, with distance based on E. coli cgMLST (EnteroBase) scheme, 2,513 columns, 200× bootstrapped. Accession numbers are from GenBank or EMBL; Black, isolates 505/58, 12698, Z, 9355, F54157, F54197, and H57237; light blue, S. dysenteriae; red, S. flexneri; green, S. boydii; pink, S. sonnei; blue, EIEC; gray, other pathotypes of E. coli.

Accession number(s).

The sequences of discrepant isolates were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA, EMBL-EBI, Cambridge, United Kingdom) as study no. PRJEB24877 with accession numbers ERR2287281 (isolate 12698), ERR2287282 (isolate 505/58), ERR2287283 (isolate 9355), ERR2300644 (isolate F54157), ERR2300645 (isolate F54197), ERR2300646 (isolate H57237), and ERR2300647 (isolate Z) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena).

RESULTS

Culture-dependent algorithm.

With the culture-dependent algorithm, an inconclusive result was obtained for four isolates (Table 2). For these isolates, a distinction between EIEC and either S. flexneri, S. boydii, or S. dysenteriae was impossible, and the Shigella O type has no known relationship to the E. coli O type. Only S. sonnei and noninvasive E. coli isolates were completely concordant with the original identification, including the inconclusive results. The obtained percentages of concordance were 92%, 85%, 93%, and 90% for S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and EIEC isolates, respectively (Table 2).

Molecular algorithm.

For 55 isolates (72%), only the ipaH gene was detected and none of the assessed wzx genes detected using the molecular algorithm. These isolates were binned in the rest group, meaning they can be either EIEC, S. sonnei phase II, S. boydii, or S. dysenteriae serotypes other than 1. All isolates except for one EIEC strain (97%) were identified in concordance with the original identification or had an inconclusive result, of which one of the results was in concordance with original identification (Table 2). One isolate had a discordant identification, although the result of the molecular algorithm was in concordance with the culture-dependent algorithm (strain H57237, Table 3).

Discrepancy analysis of discordant results.

Seven isolates showed discordant results with the original identification using the culture-dependent algorithm (Table 2), and a discrepancy analysis using WGS was carried out (Table 3). The predicted E. coli and Shigella serotypes and the presence of genes that encode for specific features are displayed in Table 3, as well as the results of the two tested algorithms (Table 3). The clustering of the discrepant isolates with reference isolates is shown in the cgMLST analysis (Fig. 2).

In the discrepancy analysis of isolate 505/58, WGS data confirmed the serotype as determined at original identification and with the culture-dependent algorithm, as the predicted serotypes are E. coli O38 and S. dysenteriae serotype 8, which are related to each other (31). However, because indole was negative, while all strains described in the literature from S. dysenteriae serotype 8 are capable of producing indole (13, 31), and because the E. coli O antigen is not typeable phenotypically (32), isolate 505/58 was identified as EIEC O-untypeable using the culture-dependent algorithm. WGS data confirmed that the tnaCAB cluster, which contains the functional genes for the production of indole from tryptophan (33), is absent in 505/58. cgMLST showed that isolate 505/58 clustered with an EIEC reference genome and not with other S. dysenteriae reference genomes in this analysis (Fig. 2). The molecular algorithm placed 505/58 in the rest group, which is in concordance with the original identification, as well as with the culture-dependent algorithm (Table 3). The clustering combined with the absence of the tnaCAB cluster indicates that 505/58 was originally misidentified as S. dysenteriae or that it has lost the tnaCAB cluster over time.

With isolate 12698, WGS data confirmed the serotype as determined at the original identification and with the culture-dependent algorithm to be S. flexneri serotype 2b. The molecular algorithm confirmed these results, as it detected the presence of the wzx1-5 gene (Table 3). However, using the culture-dependent algorithm, 12698 was repeatedly d-mannitol positive, while all described S. flexneri serotype 2b isolates are d-mannitol negative (13, 31). Because d-mannitol was positive and the E. coli O type is untypeable (32), 12698 was identified as EIEC O untypeable using the culture-dependent algorithm. The WGS data confirmed the d-mannitol-positive result, as it detected the mtlA and mtlD genes and its regulator mtlR (34). However, despite the positive result of d-mannitol fermentation, isolate 12698 clustered with S. flexneri reference isolates using cgMLST (Fig. 2), supporting the original identification, as well as the classical and in silico serotyping to designate isolate 12698 S. flexneri serotype 2b.

Discrepancy analysis using WGS for isolate Z added an additional identification instead of confirming one of the other results. Isolate Z was originally identified as S. flexneri 3a, while with the culture-dependent algorithm, the isolate fit phenotypically to S. flexneri 3a but had a serologically inconclusive serotype with antigenic formula B;6. Because the Shigella antigenic formula was inconclusive and the E. coli O type was O135 (14), isolate Z was identified as EIEC O135 with the culture-dependent algorithm. WGS analysis detected the presence of the following S. flexneri genes and clusters in isolate Z: wzx1-5, oac, gtrI, and gtr1C, resulting in S. flexneri serotype 1c (Table 3). Although the completely conserved gtrI and gtrIc clusters are present, including the gtrA and gtrB genes (35, 36), with classical Shigella serotyping, agglutination with type I and MASF 1c antisera was absent. In the cgMLST analysis, isolate Z clustered with S. flexneri reference isolates (Fig. 2). The molecular algorithm identified isolate Z as S. flexneri; however, this algorithm is not able to distinguish different serotypes (Table 3). To summarize, classical and in silico serotyping, cgMLST analysis, and the result of the molecular algorithm confirmed the original identification of isolate Z as S. flexneri but with discordances in its serotype.

In the discrepancy analysis of isolate 9355, WGS data confirmed the serotype as determined at the original identification and with the culture-dependent algorithm to be S. boydii serotype 9. However, because indole is negative, while this should be positive for S. boydii serotype 9 (13, 31), and the E. coli O type is O132, which has never been associated with EIEC, isolate 9355 was provisionally identified as Shigella using the culture-dependent algorithm. The molecular algorithm placed 9355 in the rest group, which is in concordance with original identification as well as with the culture-dependent algorithm (Table 3). The WGS data suggest that the whole tnaCAB cluster is present in isolate 9355 and contains the indole production genes tnaA, tnaB, and tnaC (33), which all encode functional proteins. Furthermore, all necessary features for the induction of tnaA and tnaB genes are present in the tnaC and rrlB genes (37, 38). The mechanism that hinders the production of indole could not be determined by assessing the presence or absence of functional genes and features and is a subject for further investigation. Isolate 9355 clustered with S. dysenteriae genomes in the cgMLST analysis. As clustering of S. boydii with S. dysenteriae was described before (5), cgMLST supports the original identification and the classical and in silico serotype to designate isolate 9355 S. boydii serotype 9.

For isolates F54157 and F54197, discrepancy analysis using WGS added an additional identification instead of confirming one of the other results. They were originally identified as EIEC O64 and as S. sonnei phase II in the culture-dependent algorithm; however, they were predicted to be E. coli O149 and S. boydii serotype 1 with WGS data (Table 3), which were described as identical antigens (31, 39). Agglutination with S. sonnei phase II antiserum in the culture-dependent algorithm could be explained by linkage between enterobacterial common antigen, which is a surface antigen present in Enterobacteriaceae, and S. sonnei phase II core oligosaccharide (40). With the molecular algorithm, isolates F54157 and F54197 were binned in the rest group, which is in concordance with the original identification, with the culture-dependent algorithm and with WGS data. Evaluation of the S. boydii serotype 1 O-antigen cluster in the WGS data in more detail showed intact wzx and wzy genes but major deletions in the rmlB gene for both isolates, explaining the lack of expression of the S. boydii serotype 1/E. coli O149 phenotype (39). In the cgMLST analysis, strains F54157 and F54197 clustered with S. dysenteriae and S. boydii strains. Overall, the discrepancy analysis based on WGS showed that isolates F54157 and F54197 were originally misidentified as EIEC with O type O64 and misidentified with the culture-dependent algorithm as S. sonnei phase II.

Isolate H57237 was originally identified as EIEC; however, both algorithms used in this study identified this isolate as S. flexneri. The serotype of H57237 is Yv, as determined by the culture-dependent algorithm and confirmed by the WGS analysis (Table 3). Serotype Yv has only recently been described (41), and probably, the original identification of this isolate predates the discovery of this novel serotype.

The discrepancy analysis showed that isolates H57237, F54157, F54197, and 505/58 might be misidentified during the original identification (Table 3 and Fig. 2). The results of the comparison of the molecular and culture-dependent algorithms with the original identification were corrected for these findings and are displayed in parentheses in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

After discrepancy analysis, the identification of S. dysenteriae, S. sonnei, and noninvasive E. coli isolates with the culture-dependent algorithm was 100% in concordance with the original identification, including the inconclusive results. For S. flexneri, S. boydii, and EIEC isolates, the concordance was 85%, 93%, and 93%, respectively.

With the molecular algorithm, 100% of the isolates were identified in concordance with the original identification after discrepancy analysis (Table 3). However, its resolution for certain serotypes is low, as it does not allow specific detection of EIEC, S. boydii, S. sonnei phase II, and S. dysenteriae serotype 2-15. Another limitation is that cross-reactivity of Shigella and E. coli O antigens is described. The primers from the S. dysenteriae wzx gene are likely to amplify the E. coli O-antigen clusters O1, O120, and O148 (31, 39), and the primers from the S. flexneri wzx1-5 gene will probably amplify the E. coli O-antigen clusters O1, O13, O16, O19, O62, O69, O73, O135, and O147 (31, 42). Of all these E. coli O types, only O135 is described as an EIEC-associated O type; none of the other E. coli O types are likely to possess the ipaH gene and are therefore not considered to be Shigella spp. or EIEC in the molecular algorithm. Nevertheless, EIEC with O type O135 cannot be separated from S. flexneri. However, this is overcome in a diagnostic setting by targeted culture from the fecal samples prompted by the results of the molecular part of the algorithm. If an isolate is selected, it is identified based on a few phenotypical key features and agglutination with Shigella and EIEC polyvalent antisera. If no isolate is selected, the physician will receive a report that Shigella spp. or EIEC is detected but without specifications about species or serotype.

One of the strengths of this study is the discrepancy analysis with WGS. This analysis is able to confirm one of the determined identities of isolates 505/58, 12698, 9355, and H57237. In contrast to those isolates, for isolates Z, F54157, and F54197, the discrepancy analysis with WGS added an extra identification result, therefore complicating the identification further instead of clarifying it.

Isolates 12698, 9355, and 505/58 were serological congruent using all identification methods, including WGS, but had one phenotypical test in discordance with their serotype (Table 3), resulting in a different identification by the culture-dependent algorithm. Phenotypical properties of a serotype are described by testing multiple isolates of the same serotype. There is not necessarily a causal connection between the serotype and the results of phenotypic tests, and phenotypic variability increases with the number of tested isolates. If the culture-dependent algorithm was applied less stringently and one phenotypical test against it was allowed, the above-described isolates were correctly identified. However, disregarding phenotypic test results should be considered carefully, because some phenotypic traits are set as defining for genus or species, for instance, the absence of LDC or d-mannitol fermentation, which are genus specific for Shigella or set as species specific for S. dysenteriae, respectively. The results of these species specific phenotypic tests should not be disregarded.

A limitation of this study is that only a few isolates of every species were used, and it is desirable to test more isolates with the proposed algorithms in the future. However, rare serotypes were difficult to obtain, and one can debate to omit these rare serotypes for test evaluation, because they are not frequently encountered in clinical diagnostics.

The here-described culture-dependent algorithm outperforms the previously described method based on the detection of the uidA gene and the lacY gene (16) that only correctly identified in silico 100% of S. sonnei, 92% of S. flexneri, 86% of S. boydii, 80% of S. dysenteriae, 77% of noninvasive E. coli, and 62% of EIEC isolates (6). In addition, the lacY gene approach is able to distinguish organisms to the genus level (16); therefore, its resolution is lower than that of the culture-dependent algorithm described in this study.

The previously described k-mer-based method outperforms the here-described culture-dependent algorithm for the identification of Shigella species, because it identified 100% of all Shigella species isolates in concordance with biochemical and serological profiling. In contrast, for identification of EIEC isolates, the proposed culture-dependent algorithm is superior, identifying 93% of EIEC isolates according to original identification, against 81.5% of EIEC isolates with the k-mer based approach (18). Furthermore, for the k-mer-based method, sequencing of whole genomes and subsequent bioinformatics analysis are required, making it less applicable in low-resource settings, where Shigella spp. are encountered frequently. Moreover, to match the resolution of the culture-dependent algorithm, extra analyses should be added to the k-mer-based method in order to determine the in silico serotype.

This study shows again that species differentiation of Shigella spp. and E. coli is challenging, as other studies have concluded before (5, 6, 18). With some isolates, differentiation is impossible, as evidenced by the percentage of isolates (5%) for which identification is inconclusive with the culture-dependent algorithm. Using the molecular algorithm, 71% of the isolates resulted in an inconclusive identification; however, this algorithm was not designed for use in the distinction between EIEC, S. boydii, S. sonnei phase II, and S. dysenteriae serotype 2-15. Nevertheless, the molecular algorithm would be sufficient for use in a developed country, because a recent study in The Netherlands (R. F. de Boer, unpublished data) showed that in 80% of ipaH gene-positive fecal samples, S. sonnei or S. flexneri is present. For use in other regions, the concept of the molecular algorithm can be adjusted to their particular needs; targets of wzx genes of S. dysenteriae and S. boydii can be added or the whole procedure can be redefined to a conventional PCR platform if real-time platforms are unavailable.

In conclusion, although not perfect, the proposed algorithms are capable of identifying most Shigella sp. and EIEC isolates. The molecular algorithm is fast and accurate and is suitable for daily application in diagnostic laboratories, as it can be performed with standard PCR equipment; however, its resolution for certain serotypes is low. The culture-dependent algorithm is more time-consuming, and many phenotypical tests and antisera are required, yet the resolution is high for all serotypes. If a desirable complete identification cannot be obtained with the molecular algorithm, the culture-dependent algorithm can be applied by a reference laboratory to obtain a higher resolution.

Despite the genetic relationship of Shigella spp. and EIEC, causing difficulties for identification, differentiation is still necessary for epidemiological and surveillance purposes because of current guidelines for infectious disease control. One can speculate if guidelines need to be adjusted, but evidence for guideline optimization with regard to infections with EIEC is currently lacking. In the future, the impact of infections with EIEC on individual patients and on public health should be further investigated to assess if it is justified that surveillance measures and control guidelines for infections with EIEC are different from those of shigellosis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Flemming Scheutz from the Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark) for providing strains.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00510-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lampel KA, Formal SB, Maurelli AT. 2018. A brief history of Shigella. EcoSal Plus 8:3. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0006-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hale TL. 1991. Genetic basis of virulence in Shigella species. Microbiol Rev 55:206–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenner DJ, Fanning GR, Steigerwalt AG, Orskov I, Orskov F. 1972. Polynucleotide sequence relatedness among three groups of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Infect Immun 6:308–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pupo GM, Lan R, Reeves PR. 2000. Multiple independent origins of Shigella clones of Escherichia coli and convergent evolution of many of their characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:10567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180094797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahl JW, Morris CR, Emberger J, Fraser CM, Ochieng JB, Juma J, Fields B, Breiman RF, Gilmour M, Nataro JP, Rasko DA. 2015. Defining the phylogenomics of Shigella species: a pathway to diagnostics. J Clin Microbiol 53:951–60. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03527-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettengill EA, Pettengill JB, Binet R. 2015. Phylogenetic analyses of Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli for the identification of molecular epidemiological markers: whole-genome comparative analysis does not support distinct genera designation. Front Microbiol 6:1573. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lan R, Alles MC, Donohoe K, Martinez MB, Reeves PR. 2004. Molecular evolutionary relationships of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. Infect Immun 72:5080–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5080-5088.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazen TH, Leonard SR, Lampel KA, Lacher DW, Maurelli AT, Rasko DA. 2016. Investigating the relatedness of enteroinvasive Escherichia coli to other E. coli and Shigella isolates by using comparative genomics. Infect Immun 84:2362–71. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00350-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Beld MJ, Friedrich AW, van Zanten E, Reubsaet FA, Kooistra-Smid MA, Rossen JW, participating Medical Microbiological Laboratories. 2016. Multicenter evaluation of molecular and culture-dependent diagnostics for Shigella species and entero-invasive Escherichia coli in the Netherlands. J Microbiol Methods 131:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Lint P, De Witte E, Ursi JP, Van Herendael B, Van Schaeren J. 2016. A screening algorithm for diagnosing bacterial gastroenteritis by real-time PCR in combination with guided culture. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 85:255–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Boer RF, Ott A, Kesztyus B, Kooistra-Smid AM. 2010. Improved detection of five major gastrointestinal pathogens by use of a molecular screening approach. J Clin Microbiol 48:4140–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01124-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkatesan MM, Buysse JM, Kopecko DJ. 1989. Use of Shigella flexneri ipaC and ipaH gene sequences for the general identification of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol 27:2687–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bopp CA, Brenner FW, Fields PI, Wells JG, Strockbine NA. 2003. Escherichia, Shigella and Salmonella, p 654–671. In Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Yolken RH (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheutz F, Strockbine NA. 2005. Genus I. Escherichia Castellani and Chalmers 1919, 9417, p 607–624. In Garrity GM. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed, vol 2 The Proteobacteria. Springer Science, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva RM, Toledo MR, Trabulsi LR. 1980. Biochemical and cultural characteristics of invasive Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol 11:441–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlovic M, Luze A, Konrad R, Berger A, Sing A, Busch U, Huber I. 2011. Development of a duplex real-time PCR for differentiation between E. coli and Shigella spp. J Appl Microbiol 110:1245–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.04973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Ryu JO, Song JY, Kim HY. 2017. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction for identification of shigellae and four Shigella species using novel genetic markers screened by comparative genomics. Foodborne Pathog Dis 14:400–406. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2016.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chattaway MA, Schaefer U, Tewolde R, Dallman TJ, Jenkins C. 2017. Identification of Escherichia coli and Shigella species from whole-genome sequences. J Clin Microbiol 55:616–623. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01790-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobersli I, Wester AL, Kristiansen A, Brandal LT. 2016. Molecular differentiation of Shigella spp. from enteroinvasive E. coli. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp) 6:197–205. doi: 10.1556/1886.2016.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse JM, Hartman AB, Strockbine N, Venkatesan M. 1995. Genetic polymorphism of the ipaH multicopy antigen gene in Shigella spps. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Microb Pathog 19:335–49. doi: 10.1016/S0882-4010(96)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrow GI, Feltham RKA. 1993. Cowan and Steel's manual for the identification of medical bacteria, 3rd ed Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Difco Laboratories. 1984. Difco manual. Difco Laboratories, Inc, Detroit, MI. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenette EH. 1985. Manual of clinical microbiology, 4th ed American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewing WH. 1986. The genus Escherichia, p 93–134. In Ewing WH. (ed), Edwards and Ewing's identification of Enterobacteriaceae, 4th ed Elsevier Science Publishing Co. Inc, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guinée PA, Agterberg CM, Jansen WH. 1972. Escherichia coli O antigen typing by means of a mechanized microtechnique. Appl Microbiol 24:127–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Beld MJ, Reubsaet FA. 2012. Differentiation between Shigella, enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) and noninvasive Escherichia coli. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:899–904. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houng HS, Sethabutr O, Echeverria P. 1997. A simple polymerase chain reaction technique to detect and differentiate Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli in human feces. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 28:19–25. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(97)89154-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Cao B, Liu B, Liu D, Gao Q, Peng X, Wu J, Bastin DA, Feng L, Wang L. 2009. Molecular detection of all 34 distinct O-antigen forms of Shigella. J Med Microbiol 58:69–81. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000794-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Q, Lan R, Wang Y, Zhao A, Zhang S, Wang J, Wang Y, Xia S, Jin D, Cui Z, Zhao H, Li Z, Ye C, Zhang S, Jing H, Xu J. 2011. Development of a multiplex PCR assay targeting O-antigen modification genes for molecular serotyping of Shigella flexneri. J Clin Microbiol 49:3766–70. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01259-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artimo P, Jonnalagedda M, Arnold K, Baratin D, Csardi G, de Castro E, Duvaud S, Flegel V, Fortier A, Gasteiger E, Grosdidier A, Hernandez C, Ioannidis V, Kuznetsov D, Liechti R, Moretti S, Mostaguir K, Redaschi N, Rossier G, Xenarios I, Stockinger H. 2012. ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res 40:W597–W603. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ewing WH. 1986. The genus Shigella, p 135–172. In Ewing WH. (ed), Edwards and Ewing's identification of Enterobacteriaceae, 4th ed Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strockbine NA, Bopp CA, Fields PI, Kaper JB, Nataro JP. 2015. Escherichia, Shigella and Salmonella, p 685–713. In Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC, Funke G, Landry ML, Richter SS, Warnock DW (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, 11th ed, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li G, Young KD. 2015. A new suite of tnaA mutants suggests that Escherichia coli tryptophanase is regulated by intracellular sequestration and by occlusion of its active site. BMC Microbiol 15:14. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moss GP. 2017. Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB). http://www.sbcs.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/. Accessed 13 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stagg RM, Tang SS, Carlin NI, Talukder KA, Cam PD, Verma NK. 2009. A novel glucosyltransferase involved in O-antigen modification of Shigella flexneri serotype 1c. J Bacteriol 191:6612–7. doi: 10.1128/JB.00628-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang SS, Carlin NI, Talukder KA, Cam PD, Verma NK. 2016. Shigella flexneri serotype 1c derived from serotype 1a by acquisition of gtrIC gene cluster via a bacteriophage. BMC Microbiol 16:127. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0746-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanofsky C. 2007. RNA-based regulation of genes of tryptophan synthesis and degradation, in bacteria. RNA 13:1141–54. doi: 10.1261/rna.620507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cruz-Vera LR, Rajagopal S, Squires C, Yanofsky C. 2005. Features of ribosome-peptidyl-tRNA interactions essential for tryptophan induction of tna operon expression. Mol Cell 19:333–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu B, Knirel YA, Feng L, Perepelov AV, Senchenkova SN, Wang Q, Reeves PR, Wang L. 2008. Structure and genetics of Shigella O antigens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:627–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gozdziewicz TK, Lugowski C, Lukasiewicz J. 2014. First evidence for a covalent linkage between enterobacterial common antigen and lipopolysaccharide in Shigella sonnei phase II ECALPS. J Biol Chem 289:2745–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Q, Lan R, Wang J, Xia S, Wang Y, Wang Y, Jin D, Yu B, Knirel YA, Xu J. 2013. Identification and characterization of a novel Shigella flexneri serotype Yv in China. PLoS One 8:e70238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perepelov AV, Shekht ME, Liu B, Shevelev SD, Ledov VA, Senchenkova SN, L'Vov VL, Shashkov AS, Feng L, Aparin PG, Wang L, Knirel YA. 2012. Shigella flexneri O-antigens revisited: final elucidation of the O-acetylation profiles and a survey of the O-antigen structure diversity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 66:201–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Q, Lan R, Wang Y, Wang J, Luo X, Zhang S, Li P, Wang Y, Ye C, Jing H, Xu J. 2011. Genesis of a novel Shigella flexneri serotype by sequential infection of serotype-converting bacteriophages SfX and SfI. BMC Microbiol 11:269. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlin NI, Rahman M, Sack DA, Zaman A, Kay B, Lindberg AA. 1989. Use of monoclonal antibodies to type Shigella flexneri in Bangladesh. J Clin Microbiol 27:1163–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheasty T, Rowe B. 1983. Antigenic relationships between enteroinvasive Escherichia coli antigens O28ac, O112ac, O124, O136, O143, O144, O152, and O164 and Shigella O antigens. J Clin Microbiol 17:681–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.