Abstract

Background: Parkinson's disease (PD) is one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases. Variants in the LRRK2 gene have been shown to be associated with PD. However, the clinical characteristics of LRRK2-related PD are heterogeneous. In our study, we performed a comprehensive pooled analysis of the association between specific LRRK2 variants and clinical features of PD.

Methods: Articles from the Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases were included in the meta-analysis. Strict inclusion criteria were applied, and detailed information was extracted from the final original articles included. Revman 5.3 software was used for publication biases and pooled and sensitivity analyses.

Results: In all, 66 studies having the clinical manifestations of PD patients with G2019S, G2385R, R1628P, and R1441G were included for the final analysis. The prominent clinical features of LRRK2-G2019S-related PD patients were female sex, higher rates of early-onset PD (EOPD), and family history (OR: 0.77 [male], 1.37, 2.62; p < 0.00001, 0.02, < 0.00001). PD patients with G2019S were more likely to have high scores of Schwab & England (MD: 1.49; p < 0.00001), low GDS scores, high UPSIT scores (MD: 0.43, 4.70; p = 0.01, < 0.00001), and good response to L-dopa (OR: 2.33; p < 0.0001). Further, G2019S carriers had higher LEDD (MD: 115.20; p < 0.00001) and were more likely to develop motor complications, such as dyskinesia and motor fluctuations (OR: 2.18, 2.02; p < 0.00001, 0.04) than non-carriers. G2385R carriers were more likely to have family history (OR: 2.10; p = 0.007) than non-G2385R carriers and lower H-Y and higher MMSE scores (MD: −0.13, 1.02; p = 0.02, 0.0007). G2385R carriers had higher LEDD and tended to develop motor complications, such as motor fluctuations (MD: 53.22, OR: 3.17; p = 0.01, < 0.00001) than non-carriers. Other clinical presentations did not feature G2019S or G2385R. We observed no distinct clinical features for R1628P or R1441G. Our subgroup analyses in different ethnic group for specific variant also presented with relevant clinical characteristics of PD patients.

Conclusions: Clinical heterogeneity was observed among LRRK2-associated PD in different variants in total and in different ethnic groups, especially for G2019S and G2385R.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, LRRK2, phenotype, clinical, meta-analysis

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second-most common neurodegenerative disease, with major clinical features comprising motor symptoms (MS) and non-motor symptoms (NMS). MS are characterized by four cardinal symptoms: bradykinesia, resting tremor, rigidity, and postural instability. NMS include olfactory dysfunction, constipation, depression, and sleep disturbance (Konno et al., 2018). Levodopa (L-dopa) is a classic treatment for parkinsonism; however, this drug is known to induce motor complications, such as dyskinesia and motor fluctuations that may affect the quality of life of PD patients (Olanow and Stocchi, 2017; Picconi et al., 2017).

In recent times, the pathogenesis of PD often remains unclear. Genetic factor, environmental factor and aging all contribute to PD pathogenesis (Liu et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is considered the most common genetic cause of PD (Paisan-Ruiz, 2009; Guo et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015); an increasing number of studies have focused on the genotype and phenotype analysis of LRRK2 and PD. Whether the clinical features of LRRK2-associated PD differ from those of idiopathic PD (IPD) is still debatable. Some researchers believe that LRRK2-related PD has similar clinical onset features to IPD, such as resting tremor, good response to L-dopa, and a benign clinical course (Orr-Urtreger et al., 2007; Paisan-Ruiz, 2009; Zheng et al., 2015). However, others have reported that LRRK2-related PD has distinct features that differ from those of IPD and vary between different genotypes (Marras et al., 2016). For example, original studies have reported that G2019S carriers are more likely to be women, less likely to develop olfactory dysfunction, and more likely to have dyskinesia and dystonia than non-carriers (Marras et al., 2016). G2385R carriers have been observed to exhibit a tendency toward motor fluctuations and are more likely to have postural instability gait disorder phenotype (Oosterveld et al., 2015). Additionally, some researchers carried out analyses of LRRK2-associated clinical features by combining different variants, without considering the different clinical features among the different variants (Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2013). Considering the heterogeneous risk of LRRK2 variants in PD, it is thus vital to provide evidence, via pooled analysis, to identify specific LRRK2 variants associated with clinical phenotypes.

Our previous comprehensive meta-analysis demonstrated the importance of LRRK2 SNPs, such as G2385R, G2019S, R1628P in PD (data unpublished). To further explore the role of LRRK2 SNPs in PD clinical features, here, we conducted a complete analysis of clinical features in specific LRRK2 variants related to PD.

Methods

Literature search

Medline database in PubMed, Embase database in Ovid, and the Cochrane databases were electronically searched by the authors for publications in English. The key words used were “Parkinson*,” “PD,” “LRRK2,” and “PARK8.” The data were assessed online on February 10, 2018. Overlapping articles from different databases were excluded. Two researchers (Li Shu and Yuan Zhang) performed the search independently. In case of disagreements, a third researcher (Qiying Sun) was consulted to arrive at a consensus.

Selection criteria

The PICOS (participants, interventions, controls, outcomes, and study types) principle was applied in the inclusion process.

Participants: all PD patients were diagnosed according to widely accepted criteria (Hughes et al., 1992) and carried specific LRRK2 variants.

Interventions: genetic analyses were conducted using genomic DNA by PCR-based methods or other accepted methods.

Controls: controls were PD patients without specific LRRK2 variants.

Outcomes: available data to calculate the number of carriers and non-carriers of the responsive phenotypes.

Study types: original case only study, case-control study, or cohort study.

Data extraction

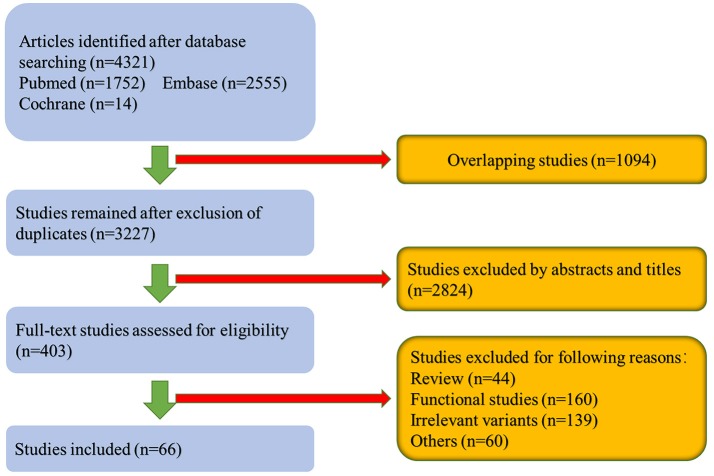

Complete data including first author, publication year, ethnicity, country, gene, variants, numbers of cases, and their responsive clinical features were extracted by two researchers (Li Shu and Yuan Zhang). If there were disputes in the process, a third author was asked to solve the problem (Qiying Sun; Table 1; Supplementary Table 1). The process of data extraction is shown in the flowchart (Figure 1). Briefly, we included studies that defined age at onset ≤ 50 years as early-onset PD (EOPD) and age at onset >50 years as late-onset PD (LOPD).

Table 1.

The publications included for phenotype analysis.

| References | Ethnicity | Country | Variants | No. patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bras et al., 2005 | European/West Asians | Portugal | G2019S | 128 |

| Lesage et al., 2006 | Africans | North Africa | G2019S | 106 |

| Gaig et al., 2006 | European/West Asians | Spain | G2019S | 302 |

| Di Fonzo et al., 2006 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 608 |

| Goldwurm et al., 2006 | European/West Asians | Italy | G2019S | 1,092 |

| Kay et al., 2006 | Mixed | America | G2019S | 1,518 |

| Clark et al., 2006 | Mixed | America | G2019S | 504 |

| Ishihara et al., 2007 | Africans | Tunis | G2019S | 201 |

| Fung et al., 2006 | East Asians | Taiwan | G2385R | 305 |

| Farrer et al., 2007 | East Asians | Taiwan | G2385R | 410 |

| Tan et al., 2007 | East Asians | Singapore | G2385R | 62 |

| Funayama et al., 2007 | East Asians | Japan | G2385R | 448 |

| Orr-Urtreger et al., 2007 | European/West Asians | Israel | G2019S | 344 |

| Li et al., 2007 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 235 |

| An et al., 2008 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 600 |

| Gan-Or et al., 2008 | European/West Asians | Israel | G2019S | 128 |

| Chan et al., 2008 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 34 |

| Hulihan et al., 2008 | Africans | Tunis | G2019S | 238 |

| Pankratz et al., 2008 | Mixed | North America | G2019S | 840 |

| Mata et al., 2009 | Hispanics | Peru,Uruguay | G2019S,R1441C | 360 |

| Lesage et al., 2008 | Africans | North Africa | G2019S | 136 |

| Latourelle et al., 2008 | Mixed | America | G2019S,R1441C | 1,025 |

| Gan-Or et al., 2008 | European/West Asians | Isreal | G2019S | 477 |

| Zhang et al., 2009 | East Asians | China | R1628P | 600 |

| Yu et al., 2009 | East Asians | China | R1628P | 328 |

| Kim et al., 2010 | East Asians | Korea | G2385R | 923 |

| Alcalay et al., 2009 | Mixed | America | G2019S | 691 |

| Belarbi et al., 2010 | Africans | Algeria | G2019S | 106 |

| Shanker et al., 2011 | European/West Asians | Isreal | G2019S | 42 |

| Hashad et al., 2011 | Africans | Egypt | G2019S | 113 |

| Saunders-Pullman et al., 2011a | Mixed | Israel and America | G2019S | 61 |

| Marras et al., 2011 | Mixed | Canada, Germany and Brazil | G2019S | 109 |

| Ben Sassi et al., 2012 | Africans | Tunis | G2019S | 110 |

| Yahalom et al., 2012 | European/West Asians | Israel | G2019S | 349 |

| Yan et al., 2012 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 354 |

| Fu et al., 2013 | East Asians | China | G2385R, R1628P | 446 |

| Sierra et al., 2013 | European/West Asians | Spain | G2019S | 79 |

| Gatto et al., 2013 | Hispanics | Argentina | G2019S | 55 |

| Cai et al., 2013 | East Asians | China | G2385R, R1628P | 510 |

| Tijero et al., 2013 | European/West Asians | Spain | G2019S, R1441C | 19 |

| Greenbaum et al., 2013 | European/West Asians | Israel | G2019S | 39 |

| Gao et al., 2013 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 175 |

| Mirelman et al., 2013 | European/West Asians | Israel | G2019S | 100 |

| Alcalay et al., 2013 | Mixed | Israel and America | G2019S | 488 |

| Trinh et al., 2014 | Africans | Tunis | G2019S | 570 |

| Yahalom et al., 2014 | European/West Asians | Israel | G2019S | 405 |

| Pulkes et al., 2014 | East Asians | Thailand | R1628P | 485 |

| Estanga et al., 2014 | European/West Asians | Spain | R1441G | 60 |

| Gaig et al., 2014 | European/West Asians | Spain | G2019S | 66 |

| Alcalay et al., 2015 | Mixed | MJFF center | G2019S | 236 |

| Nabli et al., 2015 | Africans | Tunis | G2019S | 58 |

| Saunders-Pullman et al., 2014 | Mixed | America or Israel | G2019S | 252 |

| Somme et al., 2015 | European/West Asians | Spain | G2019S, R1441C | 54 |

| Marder et al., 2015 | Mixed | MJFF center | G2019S | 474 |

| Vilas et al., 2015 | European/West Asians | Spain | G2019S | 57 |

| Saunders-Pullman et al., 2015 | Mixed | America | G2019S | 286 |

| Marras et al., 2016 | Mixed | MJFF center | G2019S, G2385R | 1,602 |

| Sun et al., 2016 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 301 |

| Dagan et al., 2016 | European/West Asians | Israel | G2019S | 211 |

| Cao et al., 2016 | East Asians | China | G2385R | 68 |

| Pal et al., 2016 | Mixed | CORE-PD | G2019S | 76 |

| Hong et al., 2017 | East Asians | Korea | G2385R | 299 |

| Bouhouche et al., 2017 | Africans | Morocco | G2019S | 100 |

| da Silva et al., 2017 | Hispanics | Brazil | G2019S | 110 |

| San Luciano et al., 2017 | Mixed | MJFF center | G2019S | 1,289 |

| Saunders-Pullman et al., 2018 | Mixed | Israel, USA | G2019S | 545 |

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the literature screening process.

Statistical analysis

Revman 5.3 software was used for all statistical analyses. Pooled odds ratio (ORs) or pooled mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs were calculated to estimate dichotomous data or continuous data about the importance of polymorphisms to the risk of phenotypes. Q statistic and I2 statistic indicated heterogeneity of the analysis. If the heterogeneity was not significant (p > 0.1, I2 < 50%), a fixed model (FM) was used for further analysis. However, if the heterogeneity was significant (p < 0.1, I2 > 50%), a random model (RM) was applied. Publication biases were measured using funnel plots. Sensitivity analyses were performed by eliminating papers one at a time, and the changes in the total results were observed.

Results

The selection process and presentation of the final results

A flowchart depicting the publication search process is shown in Figure 1. A total of 4,307 articles were retrieved after searching the databases. After excluding 1,080 overlapping articles from different databases as well as 3,161 articles that did not meet the selection criteria, 66 studies comprising 23,402 patients were considered for the final meta-analysis of phenotypes of specific LRRK2 variants related to PD. Forty-six articles comprising 16,016 patients were included for analysis of the clinical features of LRRK2-G2019S-related PD. Seventeen articles involving 6,767 patients were included for analysis of clinical presentations of LRRK2-G2385R-related PD; out of these, 5 LRRK2-R1628P–related articles comprising 2,369 patients and 5 LRRK2-R1441G–related articles comprising 1,222 patients were included in the final meta-analysis. The characteristics of the included studies in each analysis are shown in Table 1; Supplementary Table 1. The total results of meta-analyses on these four variants were shown in Table 2; Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Table 2. Besides, subgroup analyses of each variant were conducted in different ethnic groups (Africans, European/West Asians, Hispanics, East Asians and Mixed: composed of at least two different groups) according to ethnic classifications by Risch, N et al. (Risch et al., 2002; Supplementary Tables 3,4; Supplementary Figure 3).

Table 2.

The results of phenotype-association analysis of each variant of LRRK2.

| LRRK2 phenotypes or rating scales | G2019S | G2385R | R1628P | R1441G |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION | ||||

| Asymmetrical onset | − | − | NA | NA |

| Age at onset | − | − | − | NA |

| Early onset | + | − | − | NA |

| Male | + | − | − | – |

| Family history | + | + | NA | NA |

| FIRST SYMPTOMS | ||||

| FS-Bradykinesia | − | − | NA | NA |

| FS-Resting tremor | − | − | − | NA |

| FS-Rigidity | − | − | NA | NA |

| FS-Postural instability or Gait difficulty | − | − | NA | NA |

| FS-Dystonia | − | NA | NA | NA |

| FS-Micrographia | − | NA | NA | NA |

| MOTOR SYMPTOMS | ||||

| Bradykinesia | − | NA | NA | NA |

| Resting tremor | − | − | NA | NA |

| Rigidity | − | − | NA | NA |

| Postural instability or gait difficulty | − | NA | NA | NA |

| MOTOR PHENOTYPE CLASSIFICATIONS | ||||

| T-Akinetic-rigid/PIGD | − | NA | NA | NA |

| T-Mixed/Intermediate | − | NA | NA | NA |

| T-Tremor-dominant | − | NA | NA | NA |

| SCALES EVALUATING DISEASE SEVERITIES | ||||

| UPDRS I | − | − | NA | NA |

| UPDRS II | − | − | NA | NA |

| UPDRS III | − | − | NA | – |

| H-Y | − | + | − | NA |

| Schwab & England | + | NA | NA | NA |

| MOTOR COMPLICATIONS | ||||

| Dyskinesia | + | − | NA | NA |

| Motor fluctuations | + | + | NA | NA |

| NEUROPSYCHIATRIC DISTURBANCES | ||||

| Anxiety | − | NA | NA | NA |

| Depression | − | − | NA | NA |

| GDS15 | + | NA | NA | NA |

| Hallucination | − | NA | NA | NA |

| AUTONOMIC DISTURBANCES | ||||

| SCOPA-AUT | − | NA | NA | NA |

| COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENTS | ||||

| Cognitive impairments | − | NA | NA | NA |

| MMSE | − | + | NA | NA |

| MoCA | − | NA | NA | NA |

| SLEEP DISTURBANCES | ||||

| Sleep disturbances | − | NA | NA | NA |

| SENSORY COMPLAINTS | ||||

| Olfactory disturbances | − | NA | NA | NA |

| UPSIT scores | + | NA | NA | NA |

| TREATMENTS | ||||

| Good response to l-dopa | + | NA | NA | NA |

| LEDD | + | + | NA | NA |

| ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS | ||||

| Smoke | + | NA | NA | NA |

+, clinical symptoms related to a specific variant; −, clinical symptoms not related to a specific variant; NA, not available.

The clinical characteristics of LRRK2-G2019S carriers

In terms of the clinical features of specific variants, the present meta-analysis showed unique clinical manifestations in G2019S, G2385R, R1628P, and R1441G separately. In total, 40 specific clinical features or rating scales belonging to 13 classifications (Park and Stacy, 2009) were included in our meta-analysis of G2019S-related clinical characteristics (Table 2; Supplementary Table 2).

Our data show that G2019S carriers were predominantly female and had higher rates of EOPD and family history (OR: 0.77 [male], 1.37, 2.62; p < 0.00001, 0.02, < 0.00001). With respect to NMS, G2019S carriers tended to have lower Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) scores and higher University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) scores than non-carriers (MD: 0.43, 4.70; p = 0.01, < 0.00001). In terms of the response to treatment, the G2019S carriers showed good response to L-dopa (OR: 2.33; p < 0.0001) and higher Schwab and England Activity of Daily Living Scale scores (Schwab & England; MD: 1.49; p < 0.00001). Further, the G2019S carriers received a statistically higher Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) (MD: 115.20; p < 0.00001) and were more likely to develop motor complications, such as dyskinesia and motor fluctuations than non-carriers (OR: 2.18, 2.02; p < 0.00001, 0.04). Other clinical presentations did not feature G2019S.

In subgroup analyses by ethnicity, in Africans, the higher scores of UPDRSIII, more likely to develop dyskinesia were found in PD patients with G2019S variant than without G2019S variant (MD: 4.79, OR: 2.61; p: 0.0005, < 0.0001). In European/West Asians, the G2019S carriers tended to have earlier age at onset, be female, have higher rates of EOPD, family history and higher LEDD than non-carriers (MD: −2.44, OR: 0.63 [male], 1.48, 2.98, MD: 102.43; p: 0.001, < 0.0001, 0.01, < 0.00001, 0.02). In Hispanics, family history characterized G2019S carriers (OR: 4.66; p: 0.0003). In mixed ethnic group, the G2019S carriers were more likely to be female, have family history (OR: 0.77 [male], 2.22; p: < 0.00001, < 0.00001). And the carriers tended to develop akinetic-rigid motor phenotype, dyskinesia, have lower GDS scores, better response to levodopa (l-dopa), higher LEDD and smoking rates (OR: 1.85, 2.37, MD: 0.44, 2.80, 129.87, OR: 1.57; p: 0.0007, < 0.00001, 0.01, < 0.0001, < 0.00001, 0.0002). There were not enough data to analyze G2019S-related clinical features in East Asians in PD (Supplementary Tables 3, 4).

Clinical characteristics of LRRK2-G2385R carriers

In total, 20 specific clinical features or rating scales belonging to eight classifications (Park and Stacy, 2009) were included in our meta-analysis of G2385R-related clinical characteristics (Table 2; Supplementary Table 2). In the analysis of G2385R-related clinical features, we demonstrated that PD patients with G2385R variants were more likely to have family history (OR: 2.10; p = 0.007). With respect to the NMS, G2385R carriers had higher Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores than non-carriers (MD: 1.02; p = 0.0007). In terms of MS, G2385R carriers had lower Hoehn and Yahr rating (H-Y) than non-carriers (MD: −0.13; p = 0.02). In terms of treatment, G2385R carriers received statistically higher LEDD (MD: 53.22; p = 0.01) and were more likely to develop motor fluctuations than non-carriers (OR: 3.17; p < 0.00001). In terms of the other clinical features of G2385R, no statistically significant differences were observed between carriers and non-carriers.

In subgroup analyses by ethnicity, in East Asians, the PD patients with G2385R variant tended to have family history, develop motor fluctuations and have higher MMSE scores (OR: 2.1, 3.84, MD: 1.02; p: 0.007, < 0.00001, 0.0007). There were not enough data to analyze G2385R-related clinical features in other ethnic groups in PD (Supplementary Tables 3, 4).

The clinical characteristics of LRRK2-R1628P or R1441G carriers

In the analysis of R1628P-related clinical features, we included demographic information, such as age at onset, EOPD rates, sex, first symptoms, such as resting tremor, and H-Y rating. In the analysis of R1441G- related clinical characteristics, gender and UPDRSIII scores were included in the pooled analysis. No significant differences between carriers and non-carriers were observed in terms of the clinical characteristics of R1628P and R1441G. The forest plots of each analysis are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. There were no positive results of the two variants in subgroup analyses by ethnicity (Supplementary Tables 3, 4).

Statistical sensitivity and bias analysis

Articles included in the analysis focused on the relationships between the common polymorphisms and PD phenotypes. Most funnel plots of all analyses were symmetric, which indicated that there was little publication bias in the meta-analysis, except for some phenotypes (Supplementary Figures 2, 4). According to the sensitivity analysis, the pooled OR and 95% confidence interval (CI) did not change significantly when deleting each included article one at a time. The pooled OR for each analysis was stable.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis was a comprehensive pooled analysis of specific variants in LRRK2 and their associated clinical features. Detailed genotype and phenotype data were all completely included in the meta-analysis for comprehensive exploration of the important role of LRRK2 variants in PD risk.

We found that carriers of LRRK2 variants had distinct clinical features compared with non-carriers. Unique features differed between LRRK2 variants. In previous studies of LRRK2-related PD, researchers characterized LRRK2-related clinical features in patients carrying any of the LRRK2 variants, while ignoring the unique clinical features of each specific variant (Vilas et al., 2016; De Rosa et al., 2018). For example, De Rosa A et al. considered similar cognitive functions between carriers of LRRK2 G2019S or R1441G and non-carriers (De Rosa et al., 2018). However, studies of specific variants, such as R1441G reported lower likelihood of developing significant cognitive dysfunction than in IPD (Somme et al., 2015). Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the unique clinical features of LRRK2-related PD based on each specific variant.

With respect to demographic features, G2019S carriers were more likely to be female and have higher rates of EOPD and family history, while G2385R carriers were more likely to have family history. The reason that LRRK2-G2019S carriers had a higher rates of family history is that the mutation is a pathogenic non-synonymous amino acid substitution and may be a cause of familial parkinsonism besides its role in sporadic PD as a SNP like G2385R or R1628P (Mata et al., 2005). While the heritability of EOPD is high, the carriers of LRRK2-G2019S had higher rates of EOPD than non-carriers (Clark et al., 2006). The gender differences between LRRK2-G2019S carriers and non-carriers in PD may due to a heavier genetic load of female than male in PD as manifested by our analysis. Female who developed PD tended to have higher rates of genetic PD which manifested a higher rates of family history than male (Saunders-Pullman et al., 2011b). In our previous research of LRRK2 in PD, we recommended screening for specific race-associated variants, such as G2019S in Caucasian and G2385R in Asian populations (data unpublished). This previous analysis further suggested that specific demographic features, such as female sex, EOPD, or family history may be used to select a targeted population for LRRK2 screening when conducting or planning research.

Previous research indicated a more benign clinical course of G2019S-related PD compared with that for IPD; for example, lower incidence of falls, dyskinesia, cognition, and olfaction dysfunctions (Healy et al., 2008; Haugarvoll and Wszolek, 2009; Marras et al., 2011). The results of the present pooled analysis were consistent with previous results, in that G2019S carriers tended to have better quality of life as reflected by the Schwab & England scale, are less likely to be depressed, less prone to olfactory dysfunction, and show better response to L-dopa than non-carriers. The present finding that G2019S carriers exhibit less severe olfactory dysfunction was consistent with previous findings showing that abnormal olfaction function was present in up to 49% of patients, which is much lower than in IPD. (Healy et al., 2008). Other studies have suggested that LRRK2-G2019S is associated with abnormal olfactory function as a result of effects on Lewy body pathology in the rhinencephalon (Silveira-Moriyama et al., 2008; Kalia et al., 2015). G2385R carriers also presented with consistent benign clinical features, such as lower H-Y rating than non-carriers. With respect to NMS, G2385R carriers were less likely to have cognitive impairments than IPD patients, as reflected by the higher MMSE scores. We also did subgroup analyses by ethnicity and found clinical features of PD patients with LRRK2 variants especially G2019S and G2385R in specific ethnic groups. Although there were articles discussing about the genotype-phenotype correlations of LRRK2 in PD (Kestenbaum and Alcalay, 2017; Koros et al., 2017), our analysis is a pilot study which controlled the race variable and found clinical features of PD with LRRK2 variants in different ethnic groups.

The impact of pharmacogenetics on the efficacy and side effects of treatment is widely studied in the context of PD therapeutics; susceptible variants or genes have been shown to be associated with the appropriate therapeutic dosage of L-dopa or relevant motor complications. Genetic variants, such as DRD3 G3127A in the dopamine receptor (DR) gene have been shown to be involved in L-dopa-induced dyskinesia (Comi et al., 2017). G2385R in LRRK2 was previously found to be significantly associated with motor complications in female PD patients (Gao et al., 2013). Our analysis demonstrated that G2019S or G2385R carriers tend to develop motor complications with significant differences, consistent with higher LEDD, relative to non-carriers (Cacabelos, 2017). As motor complications are known to severely damage the life quality of PD patients, it is our duty, as clinicians, to minimize complications, such as dyskinesia and motor fluctuations. Our results enable deeper understanding of the underlying genetic characteristics of PD by highlighting G2019S or G2385R variants in LRRK2 as predictors for the development of motor complications, in addition to the well-established factors, such as young age at onset, higher L-dopa dose, and low body weight (Warren Olanow et al., 2013). Motor complications should be carefully considered when such patients are treated with high doses of L-dopa.

The present comprehensive analysis provides strong support for the distinct clinical features associated with different LRRK2 variants, which indicate a phenotype-genotype correlation in PD. There were phenotype-genotype correlations of other PD causative genes, such as Parkin, PINK1, and DJ1. Besides widely known clinical features of these genes like good treatment response and dyskinesia, systematic review found discrepancies from reviews or original articles. For example, Parkin mutation carriers tended to present with late age at onset and not have sleep benefit (Kasten et al., 2018). We were additionally able to predict the clinical course of PD in patients with a specific LRRK2 variant and treat these patients more precisely with early intervention to delay disease progression and control complications. The heterogeneous clinical symptoms for LRRK2-G2019S or G2385R-related PD may indicate a distinct pathophysiology in variant carriers; however, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive.

Given the nature of case-control original articles, the present meta-analysis has some inevitable limitations. First, because of the lack of sufficient data and small sample size, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis of the relationship between other widely researched variants, such as A419V and R1398H (data unpublished) and the phenotypes of PD. Therefore, more comprehensive data are needed to perfect this meta-analysis. Second, heterogeneities existed among original studies in our pooled analysis; with a greater availability of original articles, it is advisable to adjust the pooled results and aim for more robust evidence. Third, co-occurrence and interaction between the factors could not be analyzed in the present meta-analysis, which may have confounded the results.

Conclusion

Clinical heterogeneity in LRRK2-associated PD among different variants, especially for G2019S and G2385R, was found to occur. We observed no distinct clinical features for R1628P or R1441G. The prominent clinical features of LRRK2-G2019S-related PD patients were female sex and higher rates of EOPD and family history. Further, G2019S carriers were less likely to be depressive and have olfactory dysfunctions, had better response to L-dopa and better quality of life than non-carriers. Furthermore, carriers tended to be treated with higher dose of L-dopa and were more likely to develop motor complications, such as dyskinesia and motor fluctuations. With respect to the clinical symptoms of G2385R carriers, this group was more likely to have more family history, lower H-Y rating, and was less likely to develop cognitive dysfunctions than non-carriers. High-dose L-dopa treatment and related motor fluctuations were more likely to occur in PD patients carrying the G2385R variant. Other clinical presentations did not feature G2019S or G2385R. No distinct clinical features were found in R1628P or R1441G variants. Our subgroup analyses in different ethnic group also presented with relevant clinical characteristics of PD patients with G2019S and G2385R but not of R1628P or R1441G.

Author contributions

LS and YZ have contributed equally to this work and are co-first authors. LS, YZ, and QS chose the topic and designed the experiments; LS, YZ, and QS performed the analysis; LS, YZ, QS, and BT analyzed the data; LS, YZ, and QS wrote the manuscript; HP, QX, and JG: data management and figure modification.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The National Key Plan for Scientific Research and Development of China (NO. 2016YFC1306000, 2017YFC0909100) and Hunan Provincial Innovation Foundation For Postgraduate (NO. CX2017B066).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00283/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alcalay R. N., Mejia-Santana H., Mirelman A., Saunders-Pullman R., Raymond D., Palmese C., et al. (2015). Neuropsychological performance in LRRK2 G2019S carriers with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 21, 106–110. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcalay R. N., Mejia-Santana H., Tang M. X., Rosado L., Verbitsky M., Kisselev S., et al. (2009). Motor phenotype of LRRK2 G2019S carriers in early-onset Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 66, 1517–1522. 10.1001/archneurol.2009.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcalay R. N., Mirelman A., Saunders-Pullman R., Tang M. X., Mejia Santana H., Raymond D., et al. (2013). Parkinson disease phenotype in Ashkenazi Jews with and without LRRK2 G2019S mutations. Mov. Disord. 28, 1966–1971. 10.1002/mds.25647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An X. K., Peng R., Li T., Burgunder J. M., Wu Y., Chen W. J., et al. (2008). LRRK2 Gly2385Arg variant is a risk factor of Parkinson's disease among Han-Chinese from mainland China. Eur. J. Neurol. 15, 301–305. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.02052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belarbi S., Hecham N., Lesage S., Kediha M. I., Smail N., Benhassine T., et al. (2010). LRRK2 G2019S mutation in Parkinson's disease: a neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric study in a large Algerian cohort. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 16, 676–679. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Sassi S., Nabli F., Hentati E., Nahdi H., Trabelsi M., Ben Ayed H., et al. (2012). Cognitive dysfunction in Tunisian LRRK2 associated Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 18, 243–246. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhouche A., Tibar H., Ben El Haj R., El Bayad K., Razine R., Tazrout S., et al. (2017). LRRK2 G2019S mutation: prevalence and clinical features in moroccans with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons. Dis. 2017:2412486. 10.1155/2017/2412486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bras J. M., Guerreiro R. J., Ribeiro M. H., Januario C., Morgadinho A., Oliveira C. R., et al. (2005). G2019S dardarin substitution is a common cause of Parkinson's disease in a Portuguese cohort. Mov. Disord. 20, 1653–1655. 10.1002/mds.20682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacabelos R. (2017). Parkinson's disease: from pathogenesis to pharmacogenomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:E551. 10.3390/ijms18030551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Lin Y., Chen W., Lin Q., Cai B., Wang N., et al. (2013). Association between G2385R and R1628P polymorphism of LRRK2 gene and sporadic Parkinson's disease in a Han-Chinese population in south-eastern China. Neurol. Sci. 34, 2001–2006. 10.1007/s10072-013-1436-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M., Gu Z. Q., Li Y., Zhang H., Dan X. J., Cen S. S., et al. (2016). Olfactory Dysfunction in Parkinson's disease patients with the LRRK2 G2385R variant. Neurosci. Bull. 32, 572–576. 10.1007/s12264-016-0070-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D. K., Ng P. W., Mok V., Yeung J., Fang Z. M., Clarke R., et al. (2008). LRRK2 Gly2385Arg mutation and clinical features in a Chinese population with early-onset Parkinson's disease compared to late-onset patients. J Neural Transm. 115, 1275–1277. 10.1007/s00702-008-0065-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. N., Wang Y., Karlins E., Saito L., Mejia-Santana H., Harris J., et al. (2006). Frequency of LRRK2 mutations in early- and late-onset Parkinson disease. Neurology 67, 1786–1791. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244345.49809.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comi C., Ferrari M., Marino F., Magistrelli L., Cantello R., Riboldazzi G., et al. (2017). Polymorphisms of dopamine receptor genes and risk of L-dopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:242. 10.3390/ijms18020242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva C. P., de M. A. G., Cabello Acero P. H., Campos M. J., Pereira J. S., de A. R. S. R., et al. (2017). Clinical profiles associated with LRRK2 and GBA mutations in Brazilians with Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 381, 160–164. 10.1016/j.jns.2017.08.3249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan E., Schlesinger I., Kurolap A., Ayoub M., Nassar M., Peretz-Aharon J., et al. (2016). LRRK2, GBA and SMPD1 founder mutations and Parkinson's disease in ashkenazi jews. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 42, 1–6. 10.1159/000447450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa A., Peluso S., De Lucia N., Russo P., Annarumma I., Esposito M., et al. (2018). Cognitive profile and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET study in LRRK2-related Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 47, 80–83. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fonzo A., Wu-Chou Y. H., Lu C. S., van Doeselaar M., Simons E. J., Rohe C. F., et al. (2006). A common missense variant in the LRRK2 gene, Gly2385Arg, associated with Parkinson's disease risk in Taiwan. Neurogenetics 7, 133–138. 10.1007/s10048-006-0041-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estanga A., Rodriguez-Oroz M. C., Ruiz-Martinez J., Barandiaran M., Gorostidi A., Bergareche A., et al. (2014). Cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease related to the R1441G mutation in LRRK2. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20, 1097–1100. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer M. J., Stone J. T., Lin C. H., Dachsel J. C., Hulihan M. M., Haugarvoll K., et al. (2007). Lrrk2 G2385R is an ancestral risk factor for Parkinson's disease in Asia. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 13, 89–92. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Zheng Y., Hong H., He Y., Zhou S., Guo C., et al. (2013). LRRK2 G2385R and LRRK2 R1628P increase risk of Parkinson's disease in a Han Chinese population from Southern Mainland China. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 19, 397–398. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funayama M., Li Y., Tomiyama H., Yoshino H., Imamichi Y., Yamamoto M., et al. (2007). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 G2385R variant is a risk factor for Parkinson disease in Asian population. Neuroreport 18, 273–275. 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32801254b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung H. C., Chen C. M., Hardy J., Singleton A. B., Wu Y. R. (2006). A common genetic factor for Parkinson disease in ethnic Chinese population in Taiwan. BMC Neurol. 6:47. 10.1186/1471-2377-6-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaig C., Ezquerra M., Marti M. J., Munoz E., Valldeoriola F., Tolosa E. (2006). LRRK2 mutations in Spanish patients with Parkinson disease: frequency, clinical features, and incomplete penetrance. Arch. Neurol. 63, 377–382. 10.1001/archneur.63.3.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaig C., Vilas D., Infante J., Sierra M., Garcia-Gorostiaga I., Buongiorno M., et al. (2014). Nonmotor symptoms in LRRK2 G2019S associated Parkinson's disease. PLoS ONE 9:e108982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan-Or Z., Giladi N., Rozovski U., Shifrin C., Rosner S., Gurevich T., et al. (2008). Genotype-phenotype correlations between GBA mutations and Parkinson disease risk and onset. Neurology 70, 2277–2283. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304039.11891.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C., Pang H., Luo X. G., Ren Y., Shang H., He Z. Y. (2013). LRRK2 G2385R variant carriers of female Parkinson's disease are more susceptible to motor fluctuation. J. Neurol. 260, 2884–2889. 10.1007/s00415-013-7086-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto E. M., Parisi V., Converso D. P., Poderoso J. J., Carreras M. C., Marti-Masso J. F., et al. (2013). The LRRK2 G2019S mutation in a series of Argentinean patients with Parkinson's disease: clinical and demographic characteristics. Neurosci. Lett. 537, 1–5. 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldwurm S., Zini M., Di Fonzo A., De Gaspari D., Siri C., Simons E. J., et al. (2006). LRRK2 G2019S mutation and Parkinson's disease: a clinical, neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric study in a large Italian sample. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 12, 410–419. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum L., Israeli-Korn S. D., Cohen O. S., Elincx-Benizri S., Yahalom G., Kozlova E., et al. (2013). The LRRK2 G2019S mutation status does not affect the outcome of subthalamic stimulation in patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 19, 1053–1056. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. F., Li K., Yu R. L., Sun Q. Y., Wang L., Yao L. Y., et al. (2015). Polygenic determinants of Parkinson's disease in a Chinese population. Neurobiol Aging 36, 1765 e1761–1765 e1766. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashad D. I., Abou-Zeid A. A., Achmawy G. A., Allah H. M., Saad M. A. (2011). G2019S mutation of the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 gene in a cohort of Egyptian patients with Parkinson's disease. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers 15, 861–866. 10.1089/gtmb.2011.0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugarvoll K., Wszolek Z. K. (2009). Clinical features of LRRK2 parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15, S205–S208. 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70815-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy D. G., Falchi M., O'Sullivan S. S., Bonifati V., Durr A., Bressman S., et al. (2008). Phenotype, genotype, and worldwide genetic penetrance of LRRK2-associated Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 7, 583–590. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70117-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. H., Kim Y. K., Park J. S., Lee J. E., Oh M. S., Chung E. J., et al. (2017). Lack of association between LRRK2 G2385R and cognitive dysfunction in Korean patients with Parkinson's disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 36, 108–113. 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A. J., Daniel S. E., Kilford L., Lees A. J. (1992). Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 55, 181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulihan M. M., Ishihara-Paul L., Kachergus J., Warren L., Amouri R., Elango R., et al. (2008). LRRK2 Gly2019Ser penetrance in Arab-Berber patients from Tunisia: a case-control genetic study. Lancet Neurol. 7, 591–594. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70116-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara L., Gibson R. A., Warren L., Amouri R., Lyons K., Wielinski C., et al. (2007). Screening for Lrrk2 G2019S and clinical comparison of Tunisian and North American Caucasian Parkinson's disease families. Mov. Disord. 22, 55–61. 10.1002/mds.21180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia L. V., Lang A. E., Hazrati L. N., Fujioka S., Wszolek Z. K., Dickson D. W., et al. (2015). Clinical correlations with Lewy body pathology in LRRK2-related Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 72, 100–105. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasten M., Hartmann C., Hampf J., Schaake S., Westenberger A., Vollstedt E. J., et al. (2018). Genotype-phenotype relations for the Parkinson's disease genes parkin, PINK1, DJ1: MDSGene systematic review. Mov. Disord. 33, 730–741. 10.1002/mds.27352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay D. M., Bird T. D., Zabetian C. P., Factor S. A., Samii A., Higgins D. S., et al. (2006). Validity and utility of a LRRK2 G2019S mutation test for the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Genet. Test. 10, 221–227. 10.1089/gte.2006.10.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestenbaum M., Alcalay R. N. (2017). Clinical features of LRRK2 carriers with Parkinson's disease. Adv. Neurobiol. 14, 31–48. 10.1007/978-3-319-49969-7_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. M., Lee J. Y., Kim H. J., Kim J. S., Shin E. S., Cho J. H., et al. (2010). The LRRK2 G2385R variant is a risk factor for sporadic Parkinson's disease in the Korean population. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 16, 85–88. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno T., Deutschlander A., Heckman M. G., Ossi M., Vargas E. R., Strongosky A. J., et al. (2018). Comparison of clinical features among Parkinson's disease subtypes: a large retrospective study in a single center. J. Neurol. Sci. 386, 39–45. 10.1016/j.jns.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koros C., Simitsi A., Stefanis L. (2017). Genetics of Parkinson's disease: genotype-phenotype correlations. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 132, 197–231. 10.1016/bs.irn.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latourelle J. C., Sun M., Lew M. F., Suchowersky O., Klein C., Golbe L. I., et al. (2008). The Gly2019Ser mutation in LRRK2 is not fully penetrant in familial Parkinson's disease: the GenePD study. BMC Med. 6:32. 10.1186/1741-7015-6-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage S., Belarbi S., Troiano A., Condroyer C., Hecham N., Pollak P., et al. (2008). Is the common LRRK2 G2019S mutation related to dyskinesias in North African Parkinson disease? Neurology 71, 1550–1552. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338460.89796.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage S., Durr A., Tazir M., Lohmann E., Leutenegger A. L., Janin S., et al. (2006). LRRK2 G2019S as a cause of Parkinson's disease in North African Arabs. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 422–423. 10.1056/NEJMc055540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Ting Z., Qin X., Ying W., Li B., Guo Qiang L., et al. (2007). The prevalence of LRRK2 Gly2385Arg variant in Chinese Han population with Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 22, 2439–2443. 10.1002/mds.21763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K., Tang B. S., Liu Z. H., Kang J. F., Zhang Y., Shen L., et al. (2015). LRRK2 A419V variant is a risk factor for Parkinson's disease in Asian population. Neurobiol Aging 36, 2908.e2911– e2905. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Guo J., Wang Y., Li K., Kang J., Wei Y., et al. (2016). Lack of association between IL-10 and IL-18 gene promoter polymorphisms and Parkinson's disease with cognitive impairment in a Chinese population. Sci. Rep. 6:19021. 10.1038/srep19021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder K., Wang Y., Alcalay R. N., Mejia-Santana H., Tang M. X., Lee A., et al. (2015). Age-specific penetrance of LRRK2 G2019S in the Michael J. fox ashkenazi jewish LRRK2 consortium. Neurology 85, 89–95. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras C., Alcalay R. N., Caspell-Garcia C., Coffey C., Chan P., Duda J. E., et al. (2016). Motor and nonmotor heterogeneity of LRRK2-related and idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 31, 1192–1202. 10.1002/mds.26614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marras C., Schule B., Munhoz R. P., Rogaeva E., Langston J. W., Kasten M., et al. (2011). Phenotype in parkinsonian and nonparkinsonian LRRK2 G2019S mutation carriers. Neurology 77, 325–333. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227042d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata I. F., Cosentino C., Marca V., Torres L., Mazzetti P., Ortega O., et al. (2009). LRRK2 mutations in patients with Parkinson's disease from Peru and Uruguay. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15, 370–373. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata I. F., Kachergus J. M., Taylor J. P., Lincoln S., Aasly J., Lynch T., et al. (2005). Lrrk2 pathogenic substitutions in Parkinson's disease. Neurogenetics 6, 171–177. 10.1007/s10048-005-0005-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirelman A., Heman T., Yasinovsky K., Thaler A., Gurevich T., Marder K., et al. (2013). Fall risk and gait in Parkinson's disease: the role of the LRRK2 G2019S mutation. Mov. Disord. 28, 1683–1690. 10.1002/mds.25587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabli F., Ben Sassi S., Amouri R., Duda J. E., Farrer M. J., Hentati F. (2015). Motor phenotype of LRRK2-associated Parkinson's disease: a Tunisian longitudinal study. Mov. Disord. 30, 253–258. 10.1002/mds.26097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow C. W., Stocchi F. (2017). Levodopa: a new look at an old friend. Mov. Disord. 33, 859–866. 10.1002/mds.27216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterveld L. P., Allen J. C., Jr., Ng E. Y., Seah S. H., Tay K. Y., Au W. L., et al. (2015). Greater motor progression in patients with Parkinson disease who carry LRRK2 risk variants. Neurology 85, 1039–1042. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Urtreger A., Shifrin C., Rozovski U., Rosner S., Bercovich D., Gurevich T., et al. (2007). The LRRK2 G2019S mutation in Ashkenazi Jews with Parkinson disease: is there a gender effect? Neurology 69, 1595–1602. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277637.33328.d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisan-Ruiz C. (2009). LRRK2 gene variation and its contribution to Parkinson disease. Hum. Mutat. 30, 1153–1160. 10.1002/humu.21038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisan-Ruiz C., Lewis P. A., Singleton A. B. (2013). LRRK2: cause, risk, and mechanism. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 3, 85–103. 10.3233/JPD-130192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal G. D., Hall D., Ouyang B., Phelps J., Alcalay R., Pauciulo M. W., et al. (2016). Genetic and clinical predictors of deep brain stimulation in young-onset Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 3, 465–471. 10.1002/mdc3.12309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratz N., Marder K. S., Halter C. A., Rudolph A., Shults C. W., Nichols W. C., et al. (2008). Clinical correlates of depressive symptoms in familial Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 23, 2216–2223. 10.1002/mds.22285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A., Stacy M. (2009). Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. 256, 293–298. 10.1007/s00415-009-5240-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picconi B., Hernandez L. F., Obeso J. A., Calabresi P. (2017). Motor complications in Parkinson's disease: striatal molecular and electrophysiological mechanisms of dyskinesias. Mov. Disord. 33, 867–876. 10.1002/mds.27261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkes T., Papsing C., Thakkinstian A., Pongpakdee S., Kulkantrakorn K., Hanchaiphiboolkul S., et al. (2014). Confirmation of the association between LRRK2 R1628P variant and susceptibility to Parkinson's disease in the Thai population. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20, 1018–1021. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N., Burchard E., Ziv E., Tang H. (2002). Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease. Genome Biol. 3, 1–11. 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-comment2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Luciano M., Wang C., Ortega R. A., Giladi N., Marder K., Bressman S., et al. (2017). Sex differences in LRRK2 G2019S and idiopathic Parkinson's Disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 4, 801–810. 10.1002/acn3.489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders-Pullman R., Alcalay R. N., Mirelman A., Wang C., Luciano M. S., Ortega R. A., et al. (2015). REM sleep behavior disorder, as assessed by questionnaire, in G2019S LRRK2 mutation PD and carriers. Mov. Disord. 30, 1834–1839. 10.1002/mds.26413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders-Pullman R., Mirelman A., Alcalay R. N., Wang C., Ortega R. A., Raymond D., et al. (2018). Progression in the LRRK2-asssociated parkinson disease population. JAMA Neurol. 75, 312–319. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders-Pullman R., Mirelman A., Wang C., Alcalay R. N., San Luciano M., Ortega R., et al. (2014). Olfactory identification in LRRK2 G2019S mutation carriers: a relevant marker? Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 1, 670–678. 10.1002/acn3.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders-Pullman R., Stanley K., San Luciano M., Barrett M. J., Shanker V., Raymond D., et al. (2011b). Gender differences in the risk of familial parkinsonism: beyond LRRK2? Neurosci. Lett. 496, 125–128. 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders-Pullman R., Stanley K., Wang C., San Luciano M., Shanker V., Hunt A., et al. (2011a). Olfactory dysfunction in LRRK2 G2019S mutation carriers. Neurology 77, 319–324. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227041c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanker V., Groves M., Heiman G., Palmese C., Saunders-Pullman R., Ozelius L., et al. (2011). Mood and cognition in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 G2019S Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 26, 1875–1880. 10.1002/mds.23746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra M., Sanchez-Juan P., Martinez-Rodriguez M. I., Gonzalez-Aramburu I., Garcia-Gorostiaga I., Quirce M. R., et al. (2013). Olfaction and imaging biomarkers in premotor LRRK2 G2019S-associated Parkinson disease. Neurology 80, 621–626. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828250d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira-Moriyama L., Guedes L. C., Kingsbury A., Ayling H., Shaw K., Barbosa E. R., et al. (2008). Hyposmia in G2019S LRRK2-related parkinsonism: clinical and pathologic data. Neurology 71, 1021–1026. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326575.20829.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somme J. H., Molano Salazar A., Gonzalez A., Tijero B., Berganzo K., Lezcano E., et al. (2015). Cognitive and behavioral symptoms in Parkinson's disease patients with the G2019S and R1441G mutations of the LRRK2 gene. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 21, 494–499. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q., Wang T., Jiang T. F., Huang P., Li D. H., Wang Y., et al. (2016). Effect of a leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 variant on motor and non-motor symptoms in chinese Parkinson's disease patients. Aging Dis. 7, 230–236. 10.14336/AD.2015.1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E. K., Fook-Chong S., Yi Z. (2007). Comparing LRRK2 Gly2385Arg carriers with noncarriers. Mov. Disord. 22, 749–750. 10.1002/mds.21381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijero B., Gomez Esteban J. C., Somme J., Llorens V., Lezcano E., Martinez A., et al. (2013). Autonomic dysfunction in parkinsonian LRRK2 mutation carriers. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 19, 906–909. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh J., Amouri R., Duda J. E., Morley J. F., Read M., Donald A., et al. (2014). Comparative study of Parkinson's disease and leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 p.G2019S parkinsonism. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 1125–1131. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilas D., Ispierto L., Alvarez R., Pont-Sunyer C., Marti M. J., Valldeoriola F., et al. (2015). Clinical and imaging markers in premotor LRRK2 G2019S mutation carriers. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 21, 1170–1176. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilas D., Shaw L. M., Taylor P., Berg D., Brockmann K., Aasly J., et al. (2016). Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and clinical features in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) mutation carriers. Mov. Disord. 31, 906–914. 10.1002/mds.26591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren Olanow C., Kieburtz K., Rascol O., Poewe W., Schapira A. H., Emre M., et al. (2013). Factors predictive of the development of Levodopa-induced dyskinesia and wearing-off in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 28, 1064–1071. 10.1002/mds.25364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahalom G., Kaplan N., Vituri A., Cohen O. S., Inzelberg R., Kozlova E., et al. (2012). Dyskinesias in patients with Parkinson's disease: effect of the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) G2019S mutation. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 18, 1039–1041. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahalom G., Orlev Y., Cohen O. S., Kozlova E., Friedman E., Inzelberg R., et al. (2014). Motor progression of Parkinson's disease with the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 G2019S mutation. Mov. Disord. 29, 1057–1060. 10.1002/mds.25931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Ma Q., Yang X., Wang Y., Yao Y., Li H. (2012). Correlation between LRRK2 gene G2385R polymorphisms and Parkinson's disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 6, 879–883. 10.3892/mmr.2012.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W., Tang B., Zhou X., Lei L., Li K., Sun Q., et al. (2017). TMEM230 mutation analysis in Parkinson's disease in a Chinese population. Neurobiol Aging 49, 219 e211–219 e213. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Hu F., Zou X., Jiang Y., Liu Y., He X., et al. (2009). LRRK2 R1628P contributes to Parkinson's disease susceptibility in Chinese Han populations from mainland China. Brain Res. 1296, 113–116. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Shu L., Sun Q., Zhou X., Pan H., Guo J., et al. (2018). Integrated genetic analysis of racial differences of common GBA variants in Parkinson's disease: a Meta-Analysis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:43. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Burgunder J. M., An X., Wu Y., Chen W., Zhang J., et al. (2009). LRRK2 R1628P variant is a risk factor of Parkinson's disease among Han-Chinese from mainland China. Mov. Disord. 24, 1902–1905. 10.1002/mds.22371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Pei Z., Liu Y., Zhou H., Xian W., Fang Y., et al. (2015). Cognitive impairments in LRRK2-related Parkinson's disease: a study in Chinese individuals. Behav. Neurol. 2015, 621873. 10.1155/2015/621873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.