Abstract

Background

Essential arterial hypertension is one of the main treatable cardiovascular risk factors. In Germany, approximately 13% of women and 18% of men have uncontrolled high blood pressure (= 140/90 mmHg).

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective literature search in PubMed.

Results

Arterial hypertension is diagnosed when repeated measurements in a doctor’s office yield values of 140/90 mmHg or higher. The diagnosis should be confirmed by 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring or by home measurement. Further risk factors and end-organ damage should be considered as well. According to the current European guidelines, the target blood pressure for all patients, including those with diabetes mellitus or renal failure, is <140/90 mmHg. If the treatment is well tolerated, further lowering of blood pressure, with a defined lower limit, is recommended for most patients. The main non-pharmacological measures against high blood pressure are reduction of salt in the diet, avoidance of excessive alcohol consumption, smoking cessation, a balanced diet, physical exercise, and weight loss. The first-line drugs for arterial hypertension include long-acting dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers, and thiazide-like diuretics. Mineralocorticoid-receptor blockers are effective in patients whose blood pressure cannot be brought into acceptable range with first-line drugs.

Conclusion

In most patients with essential hypertension, the blood pressure can be well controlled and the cardiovascular risk reduced through a combination of lifestyle interventions and first-line antihypertensive drugs.

The World Health Organization estimates that 54% of strokes and 47% of cases of ischemic heart disease are the direct consequence of high blood pressure, which thus takes its place among the main risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (1). The declining incidence of stroke in recent decades is accounted for in large measure by the reduction of blood pressure (2). Even though the epidemiological association between high blood pressure and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is well known, and despite the fact that sufficient evidence exists to justify antihypertensive treatment (3), blood pressure is often not adequately controlled. Either the blood pressure is not measured, or the physician fails to react in the face of elevated blood pressure values (4), or treatment is not provided optimally, or the patient fails to take the necessary medication regularly (5). In patients who suffer from treatment-resistant arterial hypertension, the blood pressure cannot be adequately controlled even if the patient does take the prescribed medication regularly. In patients with essential hypertension, none of the currently available clinical methods can detect a specific cause of the elevated blood pressure. Causes of secondary hypertension such as renal artery stenosis, hyperaldosteronism, or pheochromocytoma, must be considered in the differential diagnosis, particularly in younger patients and those whose blood pressure is hard to control. Secondary types of hypertension call for specific diagnostic and therapeutic approaches (e.g., a pheochromocytoma must be resected) and will not be discussed here. In what follows, we provide an overview of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of essential arterial hypertension and derive recommendations for the treatment of the affected patients.

The direct consequences of high blood pressure.

The World Health Organization estimates that 54% of strokes and 47% of cases of ischemic heart disease are the direct consequence of high blood pressure, which is thus one of the main risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Treatment-resistant arterial hypertension.

In patients who suffer from treatment-resistant arterial hypertension, the blood pressure cannot be adequately controlled even if the patient does take the prescribed medication regularly.

Learning objectives

This article should enable the reader to

diagnose arterial hypertension and treat this leading cardiovascular risk factor,

be familiar with the definition of blood pressure target values for treatment, and

know how to treat patients in conformity with the current guidelines.

Methods

A selective search for original articles and reviews was carried out in PubMed with special attention to current guidelines and meta-analyses, which are given here as references. This article is also based on the authors’ scientific and clinical experience.

Epidemiology.

German epidemiological data from the years 2008–2011 reveal a decline in the frequency of uncontrolled hypertension from 22% to 13% in women and from 24% to 18% in men.

Epidemiology

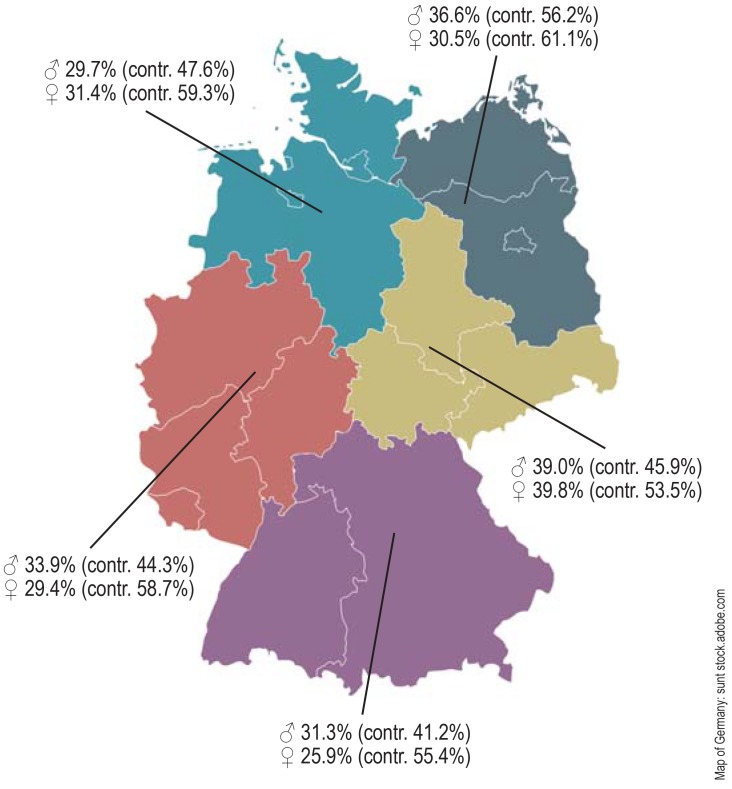

In the 1990s, the prevalence of arterial hypertension in Germany was still higher than the mean value among other Western countries. German epidemiological data from the years 2008–2011 reveal a decline in the frequency of uncontrolled hypertension from 22% to 13% in women and from 24% to 18% in men (figure 1) (6). Meanwhile, however, the prevalence among men aged 18 to 29 rose from 4.1% to 8.5%.

Figure 1.

The prevalence of arterial hypertension in five geographic regions of Germany. In the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland, DEGS1), the prevalence of arterial hypertension—defined as either documented high blood pressure values or the taking of medication to treat known hypertension—was determined in the male (♂) and female (♀) population in the period 2008–2011. The figure in parentheses is the percentage of hypertensive persons whose blood pressure was controlled with treatment [modified from [7])

Pathophysiology

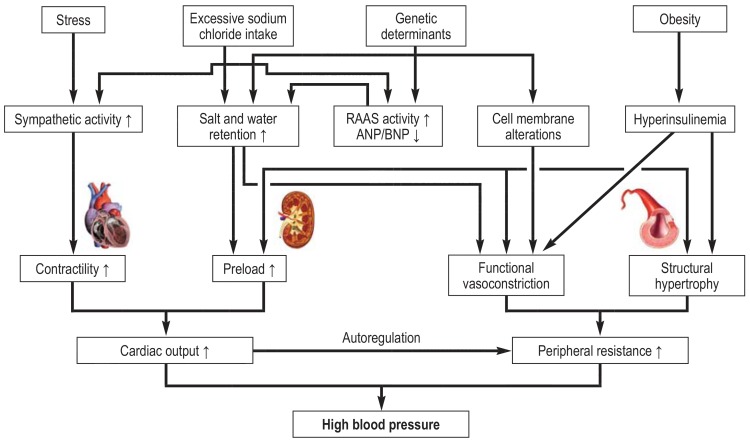

Elevated blood pressure must be due to elevated cardiac output, elevated peripheral vascular resistance, or a combination of both. Each of these mechanisms is regulated, in turn, by hemodynamic, neural, humoral, and renal processes, all of which vary in their contribution from one individual to another (figure 2). As persons grow older, the predominant cause of hypertension tends to be elevated peripheral vascular resistance, often in combination with increased stiffness of the vessels, which manifests itself clinically as isolated systolic hypertension (7). Familial clustering implies a genetic predisposition whose interaction with environmental factors, such as the intake of salt and calories and the degree of physical exercise, ultimately determines how severe the rise of blood pressure will be.

Figure 2.

The pathophysiology of essential arterial hypertension. Multiple hemodynamic, neural, humoral, and renal mechanisms lead to increased cardiac output and/or peripheral vascular resistance. The product of these two hemodynamic variables determines the blood pressure. ANP, atrial natriuertic peptide; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

Diagnostic evaluation and screening

In their current, updated joint guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension (8), the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) retain the threshold value of = 140/90 mm Hg for the definition of high blood pressure when measured in a doctor’s office. At least three measurements should be made on each of several days, with 1–2 minutes between measurements and with a 3–5 minute pause before blood pressure is measured with the patient sitting. The optimal conditions for blood pressure measurement should be maintained (box 1). Measurements from the arm in patients with an arm circumference of 22–32 cm are made with a standard cuff (12–13 cm wide, 35 cm long); for larger upper arms, cuffs that are 15–18 cm wide are available. When the blood pressure is first measured, it should be measured on both sides. If the difference in the values obtained on the two sides is >20 mmHg systolic or >10 mmHg diastolic, the following potential causes must be ruled out, and, if the blood pressure is lower on the left side, the possibility of an aortic isthmus stenosis should be considered:

BOX 1. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in the doctor’s office and at home (e16).

The bladder should be emptied before measurement.

The patient should not consume coffee, alcohol, or tobacco for at least one hour before the measurement.

The patient should be seated for 3–5 minutes before the measurement in quiet surroundings at a pleasant temperature.

Measurement in a relaxed, seated position, with backrest.

The patient’s arm should be free of clothing.

The legs should be planted on the floor, not crossed.

The arm should be relaxed and should rest on a firm surface during the measurement.

Cuff size suitable for arm circumference.

The site of the measurement should be at heart level.

At least 2 measurements should be taken 1–2 minutes apart. The patient should remain quietly seated without moving or talking.

Pathophysiology.

Elevated blood pressure must be due to elevated cardiac output, elevated peripheral vascular resistance, or a combination of both. Each of these mechanisms is regulated, in turn, by hemodynamic, neural, humoral, and renal processes, all of which vary in their contribution from one individual to another.

Aortic arch syndrome due to atherosclerosis, or, rarely, vasculitis;

Unilateral subclavian artery stenosis;

Aortic dissection.

Further measurements are subsequently always made on the arm with the higher values. Orthostatic hypotension is defined as a fall in blood pressure by more than 20 mmHg systolic and/or more than 10 mmHg diastolic after the patient has been standing for three minutes (9). If orthostatic hypotension is suspected, particularly in an elderly or diabetic patient, two further measurements should be made 1 and 3 minutes later, with the patient still standing.

The diagnosis should be confirmed by a 24-hour ambulatory measurement or by automated home blood pressure measurements. The values obtained by these methods are usually lower than those obtained in the doctor’s office. This fact is taken into account by the lower recommended cutoff values (8). A 24-hour ambulatory measurement is also particularly helpful for ascertaining the presence of white-coat hypertension or of masked hypertension.

Orthostatic hypotension.

Orthostatic hypotension is defined as a fall in blood pressure by more than 20 mmHg systolic and/or more than 10 mmHg diastolic after the patient has been standing for three minutes (9).

A patient with white-coat hypertension regularly has an elevated blood pressure in the doctor’s office, but normal values when measured at home. The prevalence of this phenomenon in the general population is approximately 13% (10). The long-term risk of cardiovascular events may be slightly higher in persons with white-coat hypertension than in persons without it (11).

In contrast, masked hypertension is the situation in which the measured blood pressure values are normal in the doctor’s office, but elevated at home. It is more common in young people, males, smokers, overweight or diabetic persons, and those suffering from anxiety or stress (12). The incidence of cardiovascular events in persons with masked hypertension is similar to that of persons with persistently elevated blood pressure (13).

White-coat hypertension.

A patient with white-coat hypertension regularly has an elevated blood pressure in the doctor’s office, but normal values when measured at home. The prevalence of this phenomenon in the general population is approximately 13%.

10–15% of persons with hypertension have secondary hypertension due to a potentially treatable cause. If the history and basic diagnostic assessment suggest this possibility (box 2), a targeted supplementary evaluation should be performed (table 1). The patient should be asked about his or her intake of substances that elevate blood pressure, including licorice, amphetamines, cocaine, oral contraceptive drugs, mineralo- and glucocorticoids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, erythropoietin, and cyclosporine. Anticancer drugs, particularly angiogenesis inhibitors and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, can also elevate blood pressure.

BOX 2. Signs suggesting secondary hypertension.

Evidence from the basic diagnostic work-up

Severe and, especially, malignant hypertension

Intractability

Persistent blood pressure elevation after a long period of good blood pressure control

Hypertension of sudden onset

Lack of a nocturnal drop in blood pressure (“non-dipper”) or even a nocturnal rise in blood pressure (“reverse dipper”) in the 24-hour long-term measurement

Unusual age of onset (before age 30 or after age 60)

Table 1. The causes, prevalence,* and diagnostic evaluation of secondary hypertension.

| Cause | Prevalence* | Primary diagnostic evaluation | Confirmatory test |

| Hyperaldosteronism | 1.4 –10% | Laboratory testing Aldosterone-renin quotient and absolute serum aldosterone concentration |

• Sodium chloride tolerance test • CT or MRI of the adrenal glands • Selective adrenal venous sampling |

| Cushing syndrome | 0.5% | Cortisol in 24-hour urine sample | Dexamethasone suppression test |

| Pheochromocytoma | 0.2 – 0.5% | Metanephrines in plasma | • CT or MRI of the abdomen • 123 I-MIBG scintigraphy |

| Thyroid diseases | 1– 2% | Measurement of serum TSH, fT3, and fT4 | Thyroid ultrasonography or scintigraphy |

| Renal parenchymal diseases | 1.6 – 8% | Renal ultrasonography Urinalysis |

Detailed work-up for renal disease |

| Renal artery stenosis | 1– 8% | Duplex ultrasonography of the kidneysand renal arteries | Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI of the renal arteries |

| Sleep apnea | >5 –15% | Polygraphy | Polysomnography |

| Aortic isthmus stenosis | <1% | Blood pressure difference right vs. left arm and upper vs. lower limb Echocardiography |

Contrast-enhanced CT or MRI of the thoracic aorta |

CT, computed tomography; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; fT3, free triiodothyronine; fT4, free tetraiodothyronine; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MIBG scintigraphy, metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy. *Prevalence in a collective of patients with arterial hypertension (e17)

High blood pressure is usually accompanied by other cardiovascular risk factors that further potentiate the risk. It follows that an evaluation of the patient’s overall risk should always be the first objective (box 3).

BOX 3. Risk factors and signs of organ damage due to hypertension*.

-

Risk factors

Male sex

Age (♂ ≥ 55 years; ♀ ≥ 65 years)

Smoking (now or in the past)

-

Dyslipidemia

Total cholesterol >190 mg/dL and/or

HDL-cholesterol ♂ <40 mg/dL; ♀ <46 mg/dL and/or

Fasting blood glucose 102–125 mg/dL

Hyperuricemia

-

Obesity

Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m² and/or

Abdominal obesity (waist circumference ♂ ≥ 102 cm; ♀ ≥ 88 cm)

Cardiovascular disease in a first-degree relative (♂ <55 years; ♀ <65 years)

Family history of early onset of arterial hypertension

Premature menopause

Sedentary lifestyle

Psychosocial and socioeconomic factors

Heart rate >80/min at rest

-

Asymptomatic end-organ damage

Pulse pressure (in an elderly individual) ≥ 60 mm Hg

Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity >10 m/s

Left-ventricular hypertrophy

Electrocardiographic signs (Sokolow–Lyon index >3.5 mV, etc.) and/or

Echocardiographic signs (left-ventricular mass index: ♂ >115 g/m²; ♀ ≥95 g/m²)

Advanced retinopathy (hemorrhges or exudates, papilledema)

Ankle–arm index <0.9

Renal failure, moderate (eGFR >30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) or severe (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2)

Microalbuminuria (30–300 mg/24 hr or 30–300 mg/g creatinine)

-

Diabetes mellitus

Fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL in at least two measurements and/or

HbA1c >7% and/or

Postprandial blood glucose ≥199 mg/dL

-

Overt cardiovascular or renal disease

-

Cerebrovascular disease

Ischemic stroke

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

Transient ischemic attack

-

-

Coronary heart disease

Myocardial infarction

Angina pectoris

Myocardial revascularization, surgical or interventional

Heart failure, systolic or diastolic

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease

Demonstration of atheromatous plaque by imaging study

Atrial fibrillation

* modified from (8), eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate

Masked hypertension.

Masked hypertension is the situation in which the measured blood pressure values are normal in the doctor’s office, but elevated at home. It is more common in young people, males, smokers, overweight or diabetic persons, and those suffering from anxiety or stress.

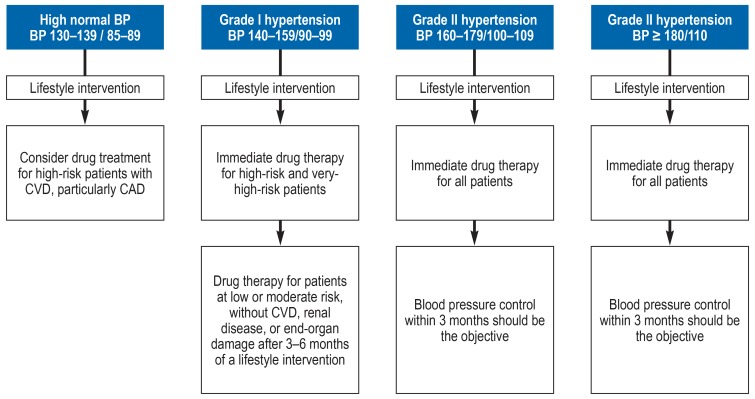

According to the current recommendation, the higher the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk, the more strictly the blood pressure should be controlled and the earlier drug treatment should be initiated (figure 4) (8). Moreover, before any treatment is given, the potential causes of secondary hypertension should be excluded (table 1). The possibility of pseudoresistance to treatment due to white-coat hypertension or suboptimal drug compliance should be borne in mind. Compliance can be checked by blood pressure measurement after supervised drug intake, or else by measurement of the active substance(s) in the patient’s serum or urine. These factors are too often left out of consideration, even by specialists (14). In one study, out of 731 patients carrying the diagnosis of treatment-resistant hypertension, 26.5% actually had either pseudoresistant essential hypertension or a secondary type of hypertension. In 47% of cases, blood pressure became normal after a suitable change in the drug regimen (14).

Figure 4.

Recommendations for the initiation of antihypertensive drug therapy depending on the initial blood pressure measured in the doctor’s office (after [8]). BP, blood pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease

Treatment

Target values for blood pressure

Blood pressure target values.

According to the update of the European ESH/ESC guidelines (2018), all patients, including those with renal failure or diabetes, should have their blood pressure reduced to less than 140/90 mmHg (as measured in the doctor’s office) at the beginning of their treatment.

According to the update of the European ESH/ESC guidelines (2018), all patients, including those with renal failure or diabetes, should have their blood pressure reduced to less than 140/90 mmHg (as measured in the doctor’s office) at the beginning of their treatment (8). Most patients will tolerate this well; for those who do, a further reduction of blood pressure is recommended. A target blood pressure range is defined, including a lower limit (8). For patients aged 18–65, a target systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg, but no less than 120 mmHg is suggested. The same holds for diabetic patients, whereas the recommendation for patients with renal failure is a somewhat higher target systolic blood pressure range (below 140 mmHg, but no less than 130 mmHg). For patients over age 65, the recommended target systolic blood pressure range is also below 140 mmHg, but no less than 130 mmHg. The target diastolic blood pressure range for all patients, regardless of age, is below 80 mmHg, but no less than 70 mmHg. In elderly patients in particular, attention must be paid to side effects, and the blood pressure target may have to be reset. The available scientific evidence on the treatment of high blood pressure in the elderly is limited, because the elderly are often excluded from clinical trials (15).

The German High Blood Pressure League recommends the reduction of blood pressure to less than 135/85 mmHg only in patients who have a high cardiovascular risk (16), stating that the advantage of low systolic blood pressure has not yet been demonstrated for hypertensive patients who suffer from diabetes mellitus, have already sustained a stroke, or are physically handicapped or dependent on nursing care.

Blood pressure target values in the NICE guideline.

NICE defines hypertension as an initial measurement of = 140/90 mmHg with subsequent measurements of = 135/85 mmHg.

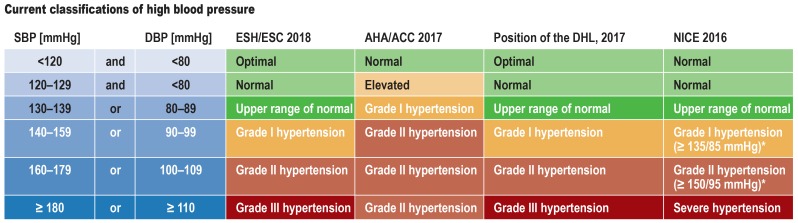

The U.S. American cardiological societies, in the most recent update of their guidelines, classify blood pressure values in the range of 130–139/85–89 mmHg as grade I hypertension, but state that this should initially be treated without drugs in most cases (figure 3) (17, 18). In the updated European guidelines, this is designated as the upper range of normal blood pressure, and it is recommended that drug treatment be considered for patients with blood pressure in this range only if their cardiovascular risk is very high (figure 4) (8). More liberal cutoff values for high blood pressure are set by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (19), which defines hypertension as an initial measurement = 140/90 mm Hg with subsequent measurements = 135/85 mm Hg (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Current classifications of high blood pressure

A comparison of the new definitions of normal blood pressure and the different grades of high blood pressure by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology

(ACC) with the definitions by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Society of Hypertension (ESH), as well as the most recent position of the German Hypertension League

(Deutsche Hochdruckliga, DHL) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) of the United Kingdom.

The lowering of cutoff values led to an increase in the prevalence of hypertension in the USA from 32% to 46%.

*The value refers to further measurements in the outpatient setting or at home.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure

High-risk patients.

The association of blood pressure with cardiovascular events in patients at high risk can be depicted by a J-shaped curve: over-aggressive blood pressure reduction (to <120 mmHg systolic or <70 mmHg diastolic) only causes more side effects without any further reduction of cardiovascular events.

The association of blood pressure with the occurrence of cardiovascular events in patients at high risk can be depicted by a J-shaped curve: over-aggressive blood pressure reduction (to <120 mmHg systolic or <70 mmHg diastolic) only causes more side effects without any further reduction of cardiovascular events (20). On the other hand, the findings of the Systolic Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) contributed to a downward trend in blood pressure cutoff values in the U.S. American and European guidelines. In this trial, 9361 patients over age 50 with a high cardiovascular risk, but without diabetes mellitus, were randomized to systolic blood pressure reduction to either <120 mmHg or <140 mm Hg (21). Over a mean follow-up time of 3.26 years, the patients with the lower blood pressure target had a lower incidence of a combined cardiovascular endpoint (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.75, 95% confidence interval: [0.64; 0.89]) and a lower risk of death from a cardiovascular cause (HR: 0.57 [0.38; 0.85]. The patients with the lower blood pressure target achieved a mean systolic blood pressure of 121 mmHg over a three-year period by taking a mean of 2.8 antihypertensive drugs, while those with the lower target achieved a mean systolic blood pressure of 134 mmHg by taking a mean of 1.8 antihypertensive drugs. The automated blood-pressure measurements in this trial were carried out after a five-minute rest period and without medical supervision, resulting in values that were a mean of 12.7/12.0 mmHg lower than those obtained in a conventional doctor’s office setting (22). It follows that these findings are not directly applicable to routine outpatient care.

A somewhat different picture arose from a Cochrane Review concerning the question whether a reduction of blood pressure by 9.5/4.9 mmHg (down to = 135/85 mmHg from starting values of 140–160/90–100 mmHg) might lower morbidity and mortality in patients already suffering from cardiovascular disease (23). Data derived from 9795 subjects, including data from SPRINT, were evaluated; no difference was seen either in overall mortality (relative risk [RR] 1.05 [0.90; 1.22]) or in cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.96 [0.77; 1.21]). Lower blood pressure did, however, lead to a 1.6% absolute risk reduction for fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events. A further meta-analysis concerned the effects of reducing blood pressure from 150–160/95–105 mmHg to <140/90 mmHg in elderly patients with a mean age of 75 years (24). A total of 8221 patients from three different trials were included in this meta-analysis, with SPRINT patients excluded for methodological reasons. There was no statistically significant effect on overall mortality, stroke, or serious cardiovascular events. Overall, it was concluded that there is an individual, relatively narrow blood pressure corridor that can be recommended for each patient on the basis of his or her age, comorbidities, and ability to tolerate the treatment. It remains to be seen whether this concept can be practically applied in routine clinical situations.

Non-pharmacological treatment

Non-pharmacological treatment.

The most important measures are a low-salt diet, adequate potassium intake, avoidance of excessive alcohol consumption, smoking cessation, a healthy, balanced diet, physical exercise, and weight loss.

The two pillars of antihypertensive treatment are non-pharmacological treatment and drug treatment (figure 4). Lifestyle changes are always to be considered first as a means of lowering blood pressure (8), and it makes sense to maintain these changes even after the later initiation of drug treatment. The most important measures are a low-salt diet, adequate potassium intake, avoidance of excessive alcohol consumption, smoking cessation, a healthy, balanced diet, physical exercise, and weight loss.

In a meta-analysis, the reduction of salt intake from 201 mmol/day (a fairly typical value for the German population) to 66 mmol/day lowered blood pressure by a mean of 5.5/2.9 mmHg in white hypertensive patients (25). The effect is variable, however: not every patient benefits from a low-salt diet. Some antihypertensive drugs, particularly inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, tend to be more effective if the patient is on a low-salt diet (26). According to the ESH/ESC guidelines, daily salt intake should not exceed 5 g (8). Potassium intake can be increased by increased consumption of vegetables and fruit.

In randomized controlled trials, regular endurance training lowered blood pressure by a mean of 11/5 mmHg (27, 28). The strongest effect was found in patients who exercised during 40- to 60-minute periods at least three times per week. A meta-analysis revealed that regular dynamic strength training can also positively affect blood pressure (29, 30).

Lifestyle changes.

In randomized controlled trials, regular endurance training lowered blood pressure by a mean of 11/5 mmHg. The strongest effect was found in patients who exercised during 40- to 60-minute periods at least three times per week.

Overweight and obese persons are at higher risk for arterial hypertension, need more antihypertensive medication, and are more commonly resistant to treatment than patients with normal weight (31, 32). It is currently recommended that all persons should have a body-mass index between 20 and 25 kg/m2, with a waist circumference less than 94 cm in men and 80 cm in women (14). The value of weight-reducing drugs for obese hypertensive patients is unclear (33, 34). The massive weight reduction brought about by bariatric surgery is associated with an initial marked improvement in blood pressure (35). Over the long term, however, this effect seems to diminish, and persistent weight reduction by at least 10 kg is needed to lower systolic blood pressure by 6 mmHg [-10.66; -1.38 mmHg] (36).

Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy

Hypertension and overweight.

Overweight and obese persons are at higher risk for arterial hypertension, need more antihypertensive medication, and are more commonly resistant to treatment than patients with normal weight. The value of weight-reducing drugs for obese hypertensive patients is unclear.

Drug treatment can be initiated with a single drug or a combined preparation (13, 37). The ESC and ESH, in their updated joint guideline, recommend that most patients should take two antihypertensive drugs at the start of pharmacotherapy, preferably combined in a single tablet (8). The recommended first line of treatment consists of preparations that are constituted from the following four drug classes: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor subtype 1 (AT1) blockers (sartans), long-acting calcium channel blockers of the dihydropyridine type, and thiazide-like diuretics (table 2). Even though beta-adrenoreceptor blockers are inferior to these substance classes with respect to cardiovascular protection (38), they are considered a suitable component of first-line treatment in some countries. Beta-blockers are used in patients who suffer from angina pectoris, have sustained a myocardial infarction in the past, or have heart failure, or else for the control of heart rate (8). On the one hand, the choice of antihypertensive drug is based on individual efficacy and tolerability, for which there are still no good predictors; on the other hand, certain antihypertensive drugs improve outcomes in patients with certain underlying diseases and should, therefore, be used preferentially in these patients (figure 5). Preparations with a long half-life that can be given once per day are preferable for reasons of compliance. In view of the circadian rhythms of circulatory regulation, it may be better for patients to take long-acting antihypertensive drugs in the evening (39), but it remains unclear whether this has any positive effect on cardiovascular events.

Table 2. Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy: dosages and common side effects*.

|

Drug class and examples |

Recommended dosage | Common side effects |

| ACE inhibitors | ||

| Benazepril | 5–40 mg/day in one or two doses |

Must not be combined with AT1-receptor antagonists; Hyperkalemia, irritative cough, elevated creatinine level in patients with chronic renal failure or renal artery stenosis, (rarely) angioedema; Contraindicated in pregnancy |

| Enalapril | 5–20 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Fosinopril | 10–40 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Lisinopril | 5–40 mg/day once daily | |

| Moexipril | 7.5–30 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Perindopril | 5–10 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Quinapril | 10–40 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Ramipril | 2.5–10 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Trandolapril | 1–4 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| AT1-receptor antagonists | ||

| Azilsartan | 40–80 mg once daily |

Must not be combined with ACE inhibitors; Hyperkalemia, elevated creatinine level in patients with chronic renal failure or renal artery stenosis;Contraindicated in pregnancy |

| Candesartan | 8–32 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Eprosartan | 600 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Irbesartan | 150–300 mg once daily | |

| Losartan | 25–100 mg/day in one or two doses | |

| Olmesartan | 10–40 mg once daily | |

| Telmisartan | 20–80 mg once daily | |

| Valsartan | 80–320 mg once daily | |

| Thiazide-like diuretics | ||

| Chlorthalidone | 12.5–25 mg/day |

Hyponatremia (mainly in elderly female patients), hypokalemia, hypovolemia |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 12.5–25 mg/day | |

| Indapamide | 2.5 mg/day | |

| Xipamide | 10–20 mg/day | |

| Calcium antagonists of the dihydropyridine type | ||

| Amlodipine | 2.5–10 mg once daily |

Leg/ankle edema, constipation |

| Felodipine | 2.5–10 mg once daily | |

| Isradipine | 2.5–10 mg once daily | |

| Nifedipine (extended-release) | 40–80 mg/day in two doses | |

| Nisoldipine | 10–40 mg/day in two doses | |

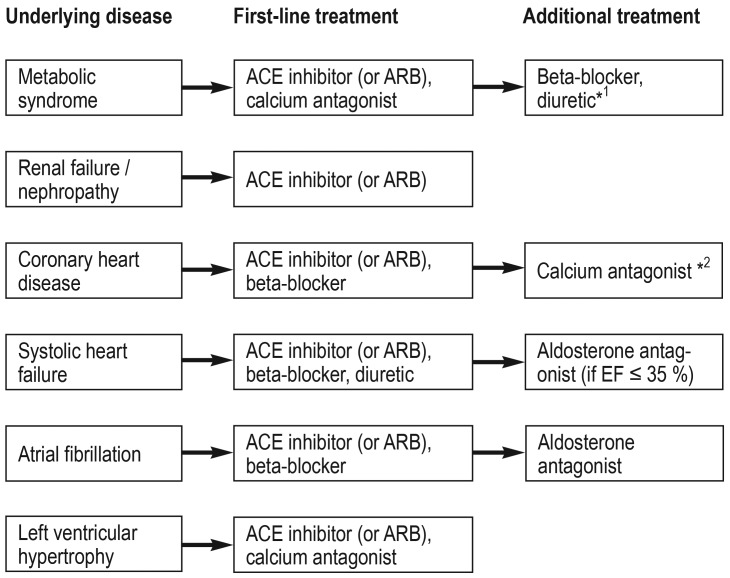

Figure 5.

Recommendations for drug treatment of arterial hypertension with additional indications for first-line treatment because of further underlying diseases.

ACE inhibitor, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker;

EF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

*1 in combination with a potassium-sparing diuretic, as indicated

*2 symptomatic treatment for angina pectoris

First-line treatment.

First-line treatment consists of preparations that are constituted from the following four drug classes: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor subtype 1 (AT1) blockers (sartans), long-acting calcium channel blockers of the dihydropyridine type, and thiazide-like diuretics.

ACE inhibitors and AT1 receptor antagonists have been extensively studied in large-scale clinical trials (40). They improve the survival of patients with heart failure and have a beneficial effect on diabetic nephropathy, and should therefore be given preferentially to patients with these conditions (figure 5). They may also lower the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (e1). Rising creatinine values and a corresponding drop in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by as much as 30% after the initiation of treatment with an ACE inhibitor or an AT1 receptor antagonist are not infrequently seen, particularly in patients with diabetic nephropathy, and should not necessarily prompt the physician to discontinue these drugs. This phenomenon is due to the desired reduction of the blood pressure faced by the renal glomeruli, resulting in a functional reduction of the eGFR. AT1 receptor antagonists carry a much lower risk of inducing cough and angioedema, but their side-effect profile is similar to that of ACE inhibitors in other respects (e2).

ACE inhibitors and AT1 receptor antagonists.

They improve the survival of patients with heart failure and have a beneficial effect on diabetic nephropathy, and should therefore be given preferentially to patients with these conditions. They may also lower the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Calcium channel blockers of the dihydropyridine type are effective antihypertensive drugs and can, in principle, be combined with any other type of first-line antihypertensive drug. Peripheral edema due to peripheral vasodilatation is a common side effect and sometimes leads to discontinuation of the drug (18). In a Cochrane analysis, the incidence of peripheral edema was 38% lower when the calcium channel blocker was given in combination with an ACE inhibitor or an AT1 receptor antagonist, probably because of the relaxation of post-capillary resistance vessels brought about by the second drug (e3). calcium channel blockers can cause or worsen constipation, particularly in elderly and immobile patients. They can also cause clinically significant drug interactions by inhibiting the enzyme cytochrome P450 3A4.

Thiazide-like diuretics have been a mainstay of antihypertensive treatment for decades (e4). Hydrochlorothiazide is the one most commonly prescribed around the world, even though it seems to be less effective than indapamide or chlorthalidone (e5). Electrolyte disturbances are a common side effect, especially in elderly patients (e6); the main types are hyponatremia and hypokalemia. 4.1% of elderly hypertensive patients treated with chlorthalidone had a serum sodium concentration below 130 mmol/L (e7). The risk of hypokalemia is lower when a thiazide diuretic is given in combination with an ACE inhibitor, an AT1 receptor antagonist, or a potassium-sparing diuretic.

Beta-blockers are inferior to other first-line antihypertensive drugs for the reduction of blood pressure (13, e8). They can cause weight gain (e9). Non-vasodilating beta-blockers have a deleterious effect on glucose metabolism (e10). Beta-blockers may worsen bronchoconstriction in patients with asthma. Nor should they be combined with verapamil or diltiazem, two drugs that can slow the sinus rhythm or prolong atrioventricular conduction. Beta-blockers do improve the prognosis of patients who have sustained an acute myocardial infarction and/or suffer from chronic congestive heart failure, and they are, therefore, indicated for patients with these conditions, independently of their antihypertensive effect (8).

ACE inhibitors and AT1 receptor antagonists are contraindicated during pregnancy. Pregnant women may take older antihypertensive drugs such as dihydralazine and alpha-methyldopa; they may also take beta-blockers, such as metoprolol, and extended-release nifedipine. Dihydralazine and nifedipine, however, should not be given during the first trimester (e11).

Treatment-resistant hypertension

Calcium channel blockers.

Calcium channel blockers of the dihydropyridine type are effective antihypertensive drugs and can, in principle, be combined with any other type of first-line antihypertensive drug. Peripheral edema due to peripheral vasodilatation is a common side effect.

Pregnancy.

ACE inhibitors and AT1 receptor antagonists are contraindicated during pregnancy. Pregnant women may take older antihypertensive drugs such as dihydralazine and alpha-methyldopa; they may also take beta-blockers, such as metoprolol, and extended-release nifedipine.

Even when all of these measures are taken, some 10% of hypertensive patients treated in routine clinical practice do not achieve adequate blood pressure control (e12, e13). The definition of treatment-resistant hypertension is blood pressure that persistently remains over 140/90 mmHg despite treatment with three antihypertensive drugs in optimal doses, one of which is a diuretic. The definition also requires the exclusion of potential causes of secondary hypertension. Treatment-resistant hypertension often turns out to be treatable once the matter of patient compliance and the potential for further improvement of the drug regimen have been properly addressed; in our experience, the true prevalence of treatment-resistant hypertension is closer to 4–5%. In these patients, the therapeutic spectrum must be widened in order to counteract the still unaltered, high cardiovascular risk.

Conclusion.

In most patients, blood pressure can be lowered effectively with first-line antihypertensive drugs, but monotherapy often does not suffice.

The treatment should be directed against two main pathophysiological mechanisms: overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system and volume excess due to excessive sodium retention, renal failure, or an excessively high aldosterone level. Hypervolemia can be countered with high-dose diuretics or with supplementary treatment with a mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonist. This was confirmed in the Pathway 2 trial (e14): 285 hypertensive patients whose mean blood pressure, measured in the doctor’s office, was 157/90 mmHg under standard treatment with an ACE inhibitor or AT1 blocker, a calcium antagonist, and a diuretic at the highest tolerated doses were given either spironolactone (25–50 mg), doxazosine (4–8 mg), bisoprolol (5–10 mg), or placebo for a period of 12 weeks in a double-blind crossover trial. If tolerated, the dose was doubled at 6 weeks. Absolute reduction of blood pressure was most pronounced with spironolactone (values of -12.8 mm Hg, -8.7 mm Hg, -8.3 mm Hg, and –4.1 mmHg, respectively). Blood pressure became normal under this treatment in 58% of patients. The frequency of serious side effects and the treatment discontinuation rate did not differ among treatment groups. Elevated activity of the sympathetic nervous system (e15) also provides the rationale for some of the interventional techniques that have been developed for this group of patients.

Conclusion

The treatment of arterial hypertension with a combination of lifestyle interventions and drugs can markedly lower cardiovascular risk. In most patients, blood pressure can be lowered effectively with first-line antihypertensive drugs, but monotherapy often does not suffice. With regard to blood pressure target values, many questions remain open. We expect that the newly altered target values will give rise to a lively discussion of their advantages and potential risks in the very near future.

Further information on CME.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 11 November 2018. Submissions by letter, e-mail or fax cannot be considered.

-

The following CME units can still be accessed for credit:

“Drug Hypersensitivity”

(issue 29–30/2018) until 14 October 2018

“Helicobacter Pylori Infection” (issue 25/2018) until 16 September 2018

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 11 November 2018.

Only one answer is possible per question. Please choose the most appropriate answer.

Question 1

How high is the prevalence of arterial hypertension in men aged 18 to 29?

5.5%

6.5%

7.5%

8.5%

9.5%

Question 2

What pathophysiological cause of hypertension often becomes most important with increasing age?

Elevation of peripheral vascular resistance

Hyperinsulinemia

Renal failure

Elevation of cardiac output

Heart failure

Question 3

Your patient’s blood pressure measurements in your office were always below 140/90 mmHg, but he obtained an elevated value on self-measurement with his wife’s sphygmomanometer. You ordered long-term measurement over 24 hours and found a mean blood pressure of 145/90 mm Hg. What is the correct diagnosis?

White-coat hypertension

Neurogenic hypertension

Normotension, because values in the doctor’s office were normal

Masked hypertension

Reverse dipper

Question 4

What underlying illness is the most common cause of secondary arterial hypertension?

Cushing syndrome

Sleep apnea

Hyperaldosteronism

Aortic isthmus stenosis

Renal artery stenosis

Question 5

What is the target blood pressure for all patients, including those with renal failure and diabetes mellitus, as recommended in the updated European ESH/ESC guideline (2018)?

<140/90 mmHg

<150/90 mmHg

<160/90 mmHg

<170/90 mmHg

<180/90 mmHg

Question 6

Which of the following persons, if hypertensive, has an elevated risk of organ damage?

58-year-old male office clerk, smoker, 106 cm waist circumference

64-year-old female farmer, heart rate 64/min at rest

58-year-old female letter carrier, fasting blood glucose 85 mg/dL

53-year-old male master carpenter, body-mass index 23 kg/m2

53-year-old female physiotherapist, menopausal, total cholesterol 165 mg/dL

Question 7

In what country did the prevalence of hypertension rise from 32% to 46% when the threshold value was lowered?

Belgium

France

Germany

The United Kingdom

The United States of America

Question 8

What lifestyle intervention lowered blood pressure by a mean of 11/5 mmHg in randomized controlled trials?

Low-cholesterol diet

Weekly physical therapy

Regular endurance training

Increased calcium intake

Relaxation training by the Jacobsen technique

Question 9

Which of the following implies that hypertension is likely to be secondary?

Night sweats

Lower blood pressure at night

Resistance to treatment

Tremor

Restless legs syndrome

Question 10

A 67-year-old woman (retired schoolteacher) with arterial hypertension and systolic heart failure is already taking an ACE inhibitor, a diuretic, and a beta-blocker as first-line treatment. Her left ventricular ejection fraction is less than 35%. What drug should you add on to her treatment?

An aldosterone antagonist

A calcium antagonist

An angiotensin receptor blocker

A benzodiazepine

A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

?Participation is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Jordan has served as a paid scientific consultant for Bayer, Eternygen, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, and Theravance. He is a co-founder of Eternygen GmbH.

Prof. Reuter has received lecture fees from, and has served as a paid consultant for, Bayer, Cordis, CVRx, Medtronic, and Servier.

Prof. Kurschat states that he shas no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lawes CM, Vander Hoorn S, Rodgers A. Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001. Lancet. 2008;371:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vangen-Lonne AM, Wilsgaard T, Johnsen SH, Lochen ML, Njolstad I, Mathiesen EB. Declining incidence of ischemic stroke: what is the impact of changing risk factors? The Tromso Study 1995 to 2012. Stroke. 2017;48:544–550. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveria SA, Lapuerta P, McCarthy BD, L‘Italien GJ, Berlowitz DR, Asch SM. Physician-related barriers to the effective management of uncontrolled hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:413–420. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Importance of therapy intensification and medication nonadherence for blood pressure control in patients with coronary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:271–276. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuhauser HK, Adler C, Rosario AS, Diederichs C, Ellert U. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control in Germany 1998 and 2008-11. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29:247–253. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace SM, Yasmin, McEniery CM, et al. Isolated systolic hypertension is characterized by increased aortic stiffness and endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 2007;50:228–233. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams B, Mancia G, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines on hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin Auton Res. 2011;21:69–72. doi: 10.1007/s10286-011-0119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagard RH, Cornelissen VA. Incidence of cardiovascular events in white-coat, masked and sustained hypertension versus true normotension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2193–2198. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282ef6185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancia G, Facchetti R, Bombelli M, Grassi G, Sega R. Long-term risk of mortality associated with selective and combined elevation in office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47:846–853. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215363.69793.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobrie G, Clerson P, Menard J, Postel-Vinay N, Chatellier G, Plouin PF. Masked hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1715–1725. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282fbcedf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persu A, Jin Y, Baelen M, et al. Eligibility for renal denervation: experience at 11 European expert centers. Hypertension. 2014;63:1319–1325. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrison SR, Kolber MR, Korownyk CS, McCracken RK, Heran BS, Allan GM. Blood pressure targets for hypertension in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011575.pub2. Cd011575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krämer BK, Hausberg M, Sanner B, et al. Blutdruckmessung und Zielblutdruck. Dtsch med Wochenschr. 2017;142:1446–1447. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-117070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. Hypertension. 2017;71:1269–1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127. last accessed on 13 July 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taler SJ. Initial treatment of hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:636–644. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1613481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright JT Jr., Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103–2016. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agarwal R. Implications of blood pressure measurement technique for implementation of systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT) J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004536. pii: e004536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saiz L, Gorricho J, Garjón J, et al. Blood pressure targets for the treatment of people with hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010315.pub4. CD010315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrison SR, Kolber MR, Korownyk CS, McCracken RK, Heran BS, Allan GM. Blood pressure targets for hypertension in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011575.pub2. Aug 8;8:Cd011575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004022.pub4. Cd004022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garfinkle MA. Salt and essential hypertension: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. JASH. 2017;11:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borjesson M, Onerup A, Lundqvist S, Dahlof B. Physical activity and exercise lower blood pressure in individuals with hypertension: narrative review of 27 RCTs. BJSM. 2016;50:356–361. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickinson HO, Mason JM, Nicolson DJ, et al. Lifestyle interventions to reduce raised blood pressure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2006;24:215–233. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000199800.72563.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacDonald HV, Johnson BT, Huedo-Medina TB, et al. Dynamic resistance training as stand-alone antihypertensive lifestyle therapy: a meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003231. pii: e003231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN, Brzezinski WA, Ferdinand KC. Uncontrolled and apparent treatment resistant hypertension in the United States, 1988 to 2008. Circulation. 2011;124:1046–1058. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bramlage P, Pittrow D, Wittchen HU, et al. Hypertension in overweight and obese primary care patients is highly prevalent and poorly controlled. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:904–910. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan J, Yumuk V, Schlaich M, et al. Joint statement of the European Association for the Study of Obesity and the European Society of Hypertension: obesity and difficult to treat arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1047–1055. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283537347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siebenhofer A, Jeitler K, Horvath K, et al. Long-term effects of weight-reducing drugs in people with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007654.pub4. Cd007654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jordan J, Astrup A, Engeli S, Narkiewicz K, Day WW, Finer N. Cardiovascular effects of phentermine and topiramate: a new drug combination for the treatment of obesity. J Hypertens. 2014;32:1178–1188. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schiavon CA, Bersch-Ferreira AC, Santucci EV, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery in obese patients with hypertension: The GATEWAY randomized trial. Circulation. 2018;137:1132–1142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sjostrom CD, Lystig T, Lindroos AK. Impact of weight change, secular trends and ageing on cardiovascular risk factors: 10-year experiences from the SOS study. Int J Obes. 2011;35:1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright JM, Musini VM, Gill R. First-line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001841.pub3. Cd001841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Fernandez JR, Portaluppi F, Fabbian F, Smolensky MH. Circadian rhythms in blood pressure regulation and optimization of hypertension treatment with ACE inhibitor and ARB medications. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:383–391. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, et al. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Abuissa H, Jones PG, Marso SP, O‘Keefe JH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Makani H, Bangalore S, Romero J, Wever-Pinzon O, Messerli FH. Effect of renin-angiotensin system blockade on calcium channel blocker-associated peripheral edema. Am J Med. 2011;124:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.[No authors listed] Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mmHg. JAMA. 1967;202:1028–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Roush GC, Ernst ME, Kostis JB, Tandon S, Sica DA. Head-to-head comparisons of hydrochlorothiazide with indapamide and chlorthalidone: antihypertensive and metabolic effects. Hypertension. 2015;65:1041–1046. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Sharabi Y, Illan R, Kamari Y, et al. Diuretic induced hyponatraemia in elderly hypertensive women. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2002;16:631–635. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.[No authors listed] Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA. 1991;265:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Wiysonge CS, Bradley HA, Volmink J, Mayosi BM, Opie LH. Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5. Cd002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Sharma AM, Pischon T, Hardt S, Kunz I, Luft FC. Hypothesis: beta-adrenergic receptor blockers and weight gain: a systematic analysis. Hypertension. 2001;37:250–254. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Bangalore S, Parkar S, Grossman E, Messerli FH. A meta-analysis of 94,492 patients with hypertension treated with beta blockers to determine the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Seely EW, Ecker J. Clinical practice Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:439–446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0804872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.de la Sierra A, Segura J, Banegas JR, et al. Clinical features of 8295 patients with resistant hypertension classified on the basis of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Hypertension. 2011;57:898–902. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Persell SD. Prevalence of resistant hypertension in the United States, 2003-2008. Hypertension. 2011;57:1076–1080. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2059–2068. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Brambilla G, et al. Marked sympathetic activation and baroreflex dysfunction in true resistant hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:1020–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–161. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Rimoldi SF, Scherrer U, Messerli FH. Secondary arterial hypertension: when, who, and how to screen? Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1245–1254. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]