Significance

This article describes a molecular realization of the classical three-body problem, where the motion of three or more bodies is directed by a set of pairwise forces. Surprisingly, motion of the components of the three-body molecular systems is found to be highly choreographed by differences in strength of intercomponent interactions, promoting a rare inchworm-like loading of molecular rings onto a molecular thread. Our work demonstrates the utility of an integrative approach to design and develop functional molecular machines.

Keywords: molecular machines, macrocycles, switching, kinetic modeling, Brownian dynamics

Abstract

The coordinated motion of many individual components underpins the operation of all machines. However, despite generations of experience in engineering, understanding the motion of three or more coupled components remains a challenge, known since the time of Newton as the “three-body problem.” Here, we describe, quantify, and simulate a molecular three-body problem of threading two molecular rings onto a linear molecular thread. Specifically, we use voltage-triggered reduction of a tetrazine-based thread to capture two cyanostar macrocycles and form a [3]pseudorotaxane product. As a consequence of the noncovalent coupling between the cyanostar rings, we find the threading occurs by an unexpected and rare inchworm-like motion where one ring follows the other. The mechanism was derived from controls, analysis of cyclic voltammetry (CV) traces, and Brownian dynamics simulations. CVs from two noncovalently interacting rings match that of two covalently linked rings designed to thread via the inchworm pathway, and they deviate considerably from the CV of a macrocycle designed to thread via a stepwise pathway. Time-dependent electrochemistry provides estimates of rate constants for threading. Experimentally derived parameters (energy wells, barriers, diffusion coefficients) helped determine likely pathways of motion with rate-kinetics and Brownian dynamics simulations. Simulations verified intercomponent coupling could be separated into ring–thread interactions for kinetics, and ring–ring interactions for thermodynamics to reduce the three-body problem to a two-body one. Our findings provide a basis for high-throughput design of molecular machinery with multiple components undergoing coupled motion.

Controlled movement is closely tied to the growth of modern civilization (1), for example, horse and cart, and combustion engine. Useful mechanical motion typically involves multiple objects. When three or more of those objects are mutually coupled together, the classical “three-body problem” emerges. Such three-body problems cannot be solved exactly despite their importance; for example, the moon’s position relative to the gravitational-coupled movements of earth and sun is critical for navigation. Solutions require approximations and numerical methods to address coupled motions. In molecular science, modeling of coupled motions in n-body problems is currently being applied to biomachines and is capable of revealing new mechanistic pathways (2). Methodologies pioneered by Szabo et al. (3) for modeling these pathways rely on identifying key reaction coordinates from molecular dynamics or Brownian dynamics simulations, and transforming reaction coordinate information into kinetics computations. These methods were instrumental in discovering kinetic rates in biomachines, for example, ATP synthesis by ATP synthase (4), ribosomal protein insertion by chaperones (5), membrane trafficking by transporters (6), and prokaryotic translation by helicases (7). These methods have only recently been applied to abiological systems, for example, cyclodextrin switches (8). Here, we extend this approach to a three-body problem involving an abiological switch—one involving threading of two rings onto a rod. Using a set of macrocyclic rings (Fig. 1 A and D), all of the evidence indicates that inchworm-like movement best describes threading with two rings following each other along the rod (Fig. 1B) as a result of ππ interactions between rings.

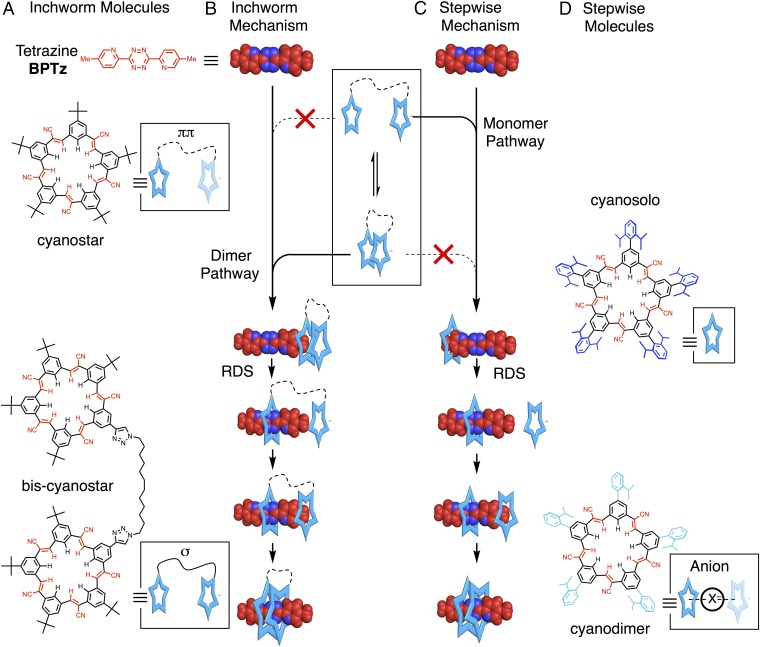

Fig. 1.

(A) Structures and cartoon representations of cyanostar ring systems (parent cyanostar and dodecyl-linked bis-cyanostar) and a tetrazine thread (colored red): 3,6-bis(5-methyl-2-pyridine)-1,2,4,5-tetrazine (BPTz). (B and C) Representations of the (B) inchworm and (C) stepwise mechanisms for threading cyanostar-based rings onto a tetrazine rod. (D) Structures and cartoon representations of cyanostar macrocycles, cyanosolo and cyanodimer, that thread onto a tetrazine rod in a stepwise manner. RDS indicates a rate-determining step.

Molecular machines and switches with three components are well represented by [3]pseudorotaxanes (9–14), [3]catenanes (15–18), and [3]rotaxanes (19–25). Examples include unidirectional motion of two small rings around a larger ring (15) and muscle-like contraction of two rings along a dumbbell in a [3]rotaxane (20). Thermodynamic bistability of two-ring systems are well described. Studies on the impact of two rings on kinetics and mechanism are considerably rarer (11, 13, 15–17, 24, 25). Kinetics can be studied when timescales of motion match techniques used for observing switching (11, 13, 24, 26–32). Here, we take advantage of cyclic voltammetry (CV) to study redox-driven kinetics and mechanism of switching on 1-ms to 10-s timescales.

We have previously described switches composed of two rings and a single tetrazine thread exemplifying the three-body problem. With copper(I)-phenanthroline rings (13), there are no inter-ring interactions and the rings can be considered independent of each other. Stepwise threading of a first ring onto a tetrazine anion produced an observable [2]pseudorotaxane intermediate with a rate constant of 55,000 M−1⋅s−1. The slower threading of the second ring (13,000 M−1⋅s−1) reflects steric interactions between rings. A second example involved threading of two planar cyanostar (CS, Fig. 1A) macrocycles onto a tetrazine thread (12, 33–37). The threading mechanism was not determined (12) because CV signatures did not conform to the expected production of an intermediate, as observed with copper(I)-phenanthroline. Here, we describe a detailed analysis of this unexpected outcome.

Threading of two rings onto a rod-like thread can follow multiple pathways. The threading of two rings as a single unit is least likely unless they are affixed intimately together. More likely is the independent, stepwise threading of rings to produce an observable intermediate with a slower second step (Fig. 1C) (13). Last, two rings can thread in an inchworm movement (Fig. 1B) with one ring following the other but only if the motions of the two rings are coupled. An inchworm mechanism was previously proposed to describe kinesin (38) and myosin (39), but later ruled out in favor of hand-over-hand motion by single-molecule studies (38, 39). The inchworm mechanism is presently on the table for the dynein motor motion (40); however, it has not yet been observed in abiological contexts.

Here, we show that when two cyanostar rings are coupled together by noncovalent (ππ) or covalent (σ) bonds, they thread like an inchworm onto one side of a thread. The components (Fig. 1A) are cyanostar macrocycles (the rings) that thread onto a disubstituted tetrazine (the rod): 3,6-bis(5-methyl-2-pyridine)-1,2,4,5-tetrazine (BPTz) (10–13). The cyanostar self-associates into π-stacked multimers with Ke = 225 M−1 (13 kJ⋅mol−1, CH2Cl2) (33), and threading is initiated by the tetrazine’s reduction to the anion, BPTz–. Control compounds help distinguish inchworm from stepwise pathways for cyanostar threading. Inchworm movements followed by a covalently linked bis-cyanostar (Fig. 1A) produce CVs with no intermediates. This behavior matches the parent cyanostar. In contrast, a macrocycle designed to exist as a single ring by inhibiting self-association until it binds an anion (Fig. 1D, cyanodimer), displays the characteristic intermediate of a stepwise mechanism. The inchworm mechanism is then interrogated using a consistent digital simulation of the CVs to generate rate constants for switching. With barriers and wells determined from CV simulations, kinetics and Brownian dynamics simulations provided mean first-passage times of cyanostar motion at different stages of the pathway (3). We tested and confirmed the idea that the kinetics description of the three-body problem could be simplified to just two-component couplings between ring and thread because ring–ring interactions mostly only influence thermodynamics. These findings provide a basis for high-throughput design (41) of molecular machinery using simulations (42) to evaluate the synchronized movements of multiple coupled components (18).

Results and Discussion

Time Dependence of Redox-Driven Switching.

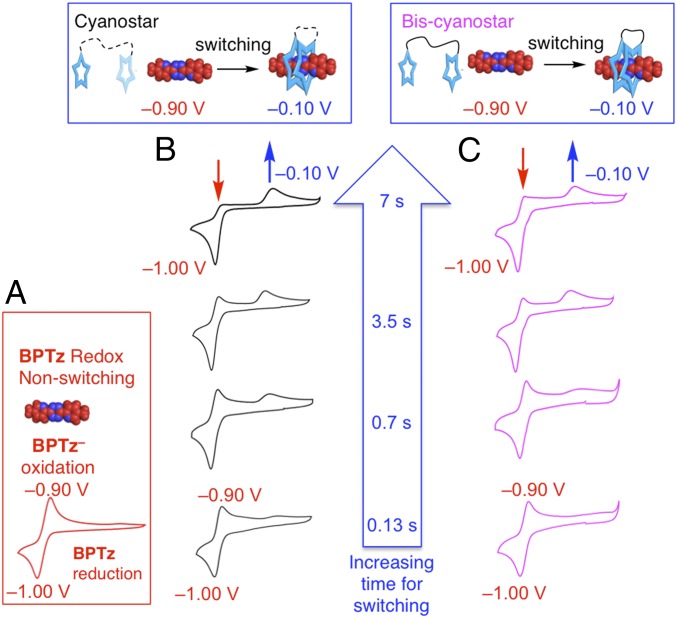

The switching process involves reduction of tetrazine to generate the anion, which drives threading with two macrocycles to produce the doubly threaded [3]pseudorotaxane. Consistently, a traditional switching signature is seen in the CV (12). The free tetrazine displays (Fig. 2A) a reversible reduction with cathodic peak at Epc = −1.00 V (vs. Ag wire pseudoreference) and corresponding anodic peak at Epa = −0.90 V. With 2 eq of cyanostar, the CV recorded as a function of scan rate (Fig. 2B) show changes indicative of switching kinetics (12). A slow scan rate (0.1 V⋅s−1) allows adequate time (∼7 s) for switching. Complete threading of two macrocycles occurs after reduction to the anion BPTz– yet before the anion’s deactivation by oxidation at approximately −0.9 V. The intensity of the reoxidation peak decreases with a concomitant growth in intensity of the new reoxidation peak at −0.10 V (Fig. 2B). This peak is assigned (12) to the threaded product, CS2•BPTz–. In contrast, switching is incomplete at faster scan rates (5 V⋅s−1, Fig. 3B), which allows only 140 ms for switching. This time is defined by the scan rate when the voltage sweeps 700 mV from −1.0 V out to the vertex at −1.3 V and back to −0.9 V. No intermediate peaks for the singly threaded [2]pseudorotaxane are observed across all scan rates (0.1–10 V⋅s−1) and concentrations (0.5 and 2.5 mM).

Fig. 2.

Electrochemical CV traces of (A) BPTz alone and (B) the switching system with 2 eq of cyanostar added (1.0 mM BPTz, 2.0 mM cyanostar). (C) Matching variable scan rate CVs of BPTz (1.0 mM) with 1 eq of the bis-cyanostar (1.0 mM). Conditions: 0.1 M TBABPh4, CH2Cl2 N2, variable scan rate, 1.0-mm glassy carbon wire working electrode, platinum wire counter electrode, AgO wire quasireference, 298 K, all referenced to Epc BPTz = −1.00 V. Times defined by scan rates: 7 s (0.1 V⋅s−1), 3.5 s (0.2 V⋅s−1), 0.7 s (1 V⋅s−1), and 0.14 s (5 V⋅s−1).

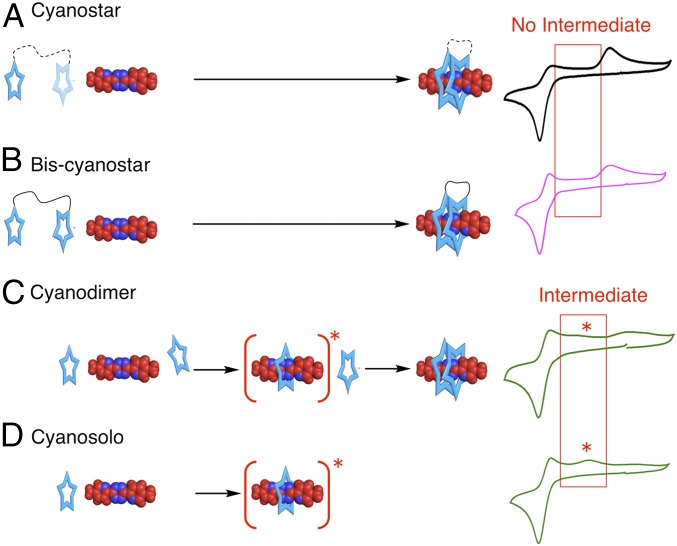

Fig. 3.

Experimental CVs of switching with signatures that show no intermediates—parent cyanostar (A) and bis-cyanostar (B)—compared with the CV signatures that show a signal for the [2]pseudorotaxane intermediate—cyanodimer (C) and cyanosolo (D). Conditions: 0.2 V⋅s−1; all other conditions are the same as Fig. 2.

Qualitative Studies with Control Compounds.

A key difference in CVs recorded with cyanostar (Fig. 2B) relative to copper(I)-phenanthroline (13) is the absence of an observable intermediate. This outcome is attributed to the coupling between cyanostars producing dimers (CS)2 and higher-order multimers (CS)n by the following equilibria:

| [1a] |

| [1b] |

To test for the role of coupling between macrocycles as represented by dimer (CS)2 in Eq. 1, we used a covalently linked pair of macrocycles. The covalently linked bis-cyanostar (Fig. 1A) is expected to reflect an inter-ring coupled state. It is unlikely that the second macrocycle can reach over to the other end of the tetrazine, as it requires a fully extended dodecyl chain. There is a sizable energy cost of 24 kJ⋅mol−1 (43) associated with the loss of configurational entropy in this extended chain. Thus, threading will proceed by the inchworm pathway. Both the covalently linked and noncovalently linked rings display similar CVs (compare Fig. 2 B and C). In both cases, there is no intermediate. We infer, therefore, that both the molecules thread by the same pathway, namely the inchworm.

Cyanodimer (Fig. 1D) is an excellent control macrocycle. It has been designed to exclude inter-ring interactions and only form a dimer when complexed with an anion. It cannot proceed via an inchworm pathway and is predicted, instead, to switch by a stepwise mechanism. As expected, it displays (Fig. 3C) an intermediate that is indicative of the stepwise pathway when examined under similar conditions as the parent cyanostar (Fig. 3A) and bis-cyanostar (Fig. 3B). The oxidation peak position of the intermediate was confirmed using the CV (Fig. 3D) obtained on a model compound denoted cyanosolo (36). This macrocycle (Fig. 1C) bears bulky groups, only threads a single ring, and matches the oxidation peak of the cyanodimer intermediate (Fig. 3C vs. Fig. 3D). Altogether, the CV of noncoupled cyanodimer is in complete contrast to the parent cyanostar, indicating that coupling is responsible for their differences in behavior.

Quantitative Mechanistic Model of the Inchworm Pathway.

All CVs are consistent with the parent cyanostar threading along an inchworm pathway (Fig. 4 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6). This model satisfies the observation that the parent cyanostar displays the same CV and inchworm pathway as the bis-cyanostar; both do not have intermediates. Both of these coupled macrocycles have different CVs and behavior relative to the cyanodimer’s stepwise threading. Only the inchworm mechanism can generate a self-consistent set of rate constants for the kinetics of motion.

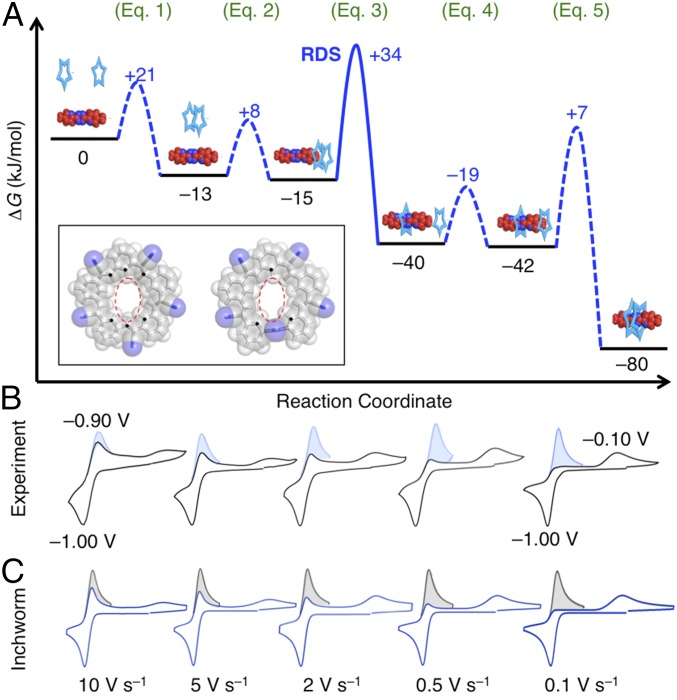

Fig. 4.

(A) Reaction coordinate with free energies used in the CV simulations showing the inchworm model of switching involving threading of two cyanostar macrocycles onto the BPTz– thread. (Inset) Threading likely occurs with one cyanostar (at Left) undergoing 90° olefin rotation (at Right) to accommodate the cross-sectional area of BPTz– (broken red oval). (B and C) Experimental CVs of the parent cyanostar recorded as a function of scan rate (B) compared with digital simulations of the CVs (C). The shaded regions are an inversion of the cathodic peak added onto the primary data to help guide assessment of current ratios.

To quantify kinetics, we used a standard approach (10, 11, 13, 26). The variation in CV peak intensities with scan rate is reproduced using digital simulations based on possible mechanisms of switching. CV simulations employ experimentally determined (12) and estimated thermodynamics, diffusion coefficients, and chemical and electron-transfer reactions. The absence of an intermediate arises when the second step is fast enough to consume intermediates. This boundary condition needs to be fulfilled in a mechanistic model. The final model (Fig. 4A) includes microscopic states reasonably indicated from experiment (SI Appendix, section 7).

In the inchworm model (Fig. 4A), two cyanostar macrocycles come together when the thermodynamically favored dimer is formed according to Eq. 1. About ∼21% of the cyanostars in solution (2.5 mM) reside as the dimer relative to the monomer (44%), trimer (7%), tetramer (7%), and higher-order multimers (20%) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Rapid equilibration among these allows the dimer to be reformed. On account of weak association seen between diglyme and cyanostar (β2 = 30 M−1, ΔG = −8 kJ⋅mol−1) (35), we introduce a step in the mechanism involving weak association (ΔG = −2 kJ⋅mol−1, Eq. 2 and Fig. 4A) with the reduced thread, CS2@BPTz–. Subsequently, macrocycles thread one by one like an inchworm. This first threading (Eq. 3) makes a [2]pseudorotaxane intermediate, which rapidly associates with the second cyanostar (Eq. 4) and converts into product by threading of the second ring (Eq. 5).

This inchworm model successfully reproduced all experimental CVs (Fig. 4 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6). Simulated CVs match experiment as a function of scan rate. Modeling shows the first threading occurs with rate constant 7,000 ± 1,000 s−1 (Eq. 3). The second threading has a rate constant of 7,000 s−1 (Eq. 5), which is a lower bound and is sufficient to ensure the intermediate is consumed. Variation in concentration was used to test the model. We find a single unified set of rate constants reproduce the CVs recorded at 2.5 and 0.5 mM.

We also conducted digital simulations of the CVs using the stepwise mechanism. We are not able to generate a single unified set of rate constants to reproduce the experimental CVs across both scan rate and concentration. Rate constants for the first and second steps developed at the lower concentration of 0.5 mM (700 ± 200 and 7,000 s−1; SI Appendix, Fig. S5) are significantly different, and do not match, those at the higher concentration of 2.5 mM (2,500 ± 500 and 25,000 s−1; SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Defining the Energy–Distance Coordinate.

With the inchworm mechanism refined using digital simulations of the CVs, we developed a mechanical model of motion to probe this three-body system with statistical mechanical computations. This mechanical model involved transforming the reaction coordinate space (Fig. 4A) into a spatial basis (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). The movement of two rings was considered relative to the frame of the thread. For simplicity, only translational walks along the X axis were considered, although rotations/deformations of the ring can also be incorporated (SI Appendix, section 5). The threading pathway in this three-body problem involves interring interactions coupled to ring–thread interactions. For this reason, even the most elementary translation-based inchworm reaction coordinate requires monitoring two Cartesian variables, location of the rings on the thread and inter-ring distance. Given this complexity, we needed to simplify the problem.

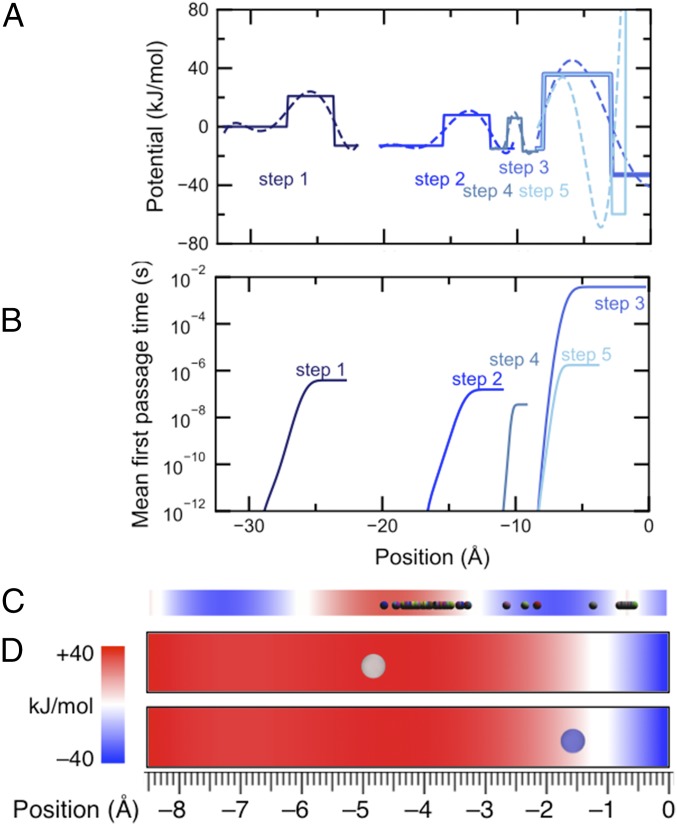

Fig. 5.

(A) Block diagrams describing each step in the inchworm mechanism needed for the kinetics simulations. The block diagrams include sixth-order polynomial fits overlays to represent smooth free-energy profiles along the reaction coordinate cast in terms of cyanostar position relative to the BPTz thread. (B) Mean first-passage time of cyanostar moving along this reaction coordinate computed from Eq. 6 illustrates that step 3 (first threading event) is the slowest, determining the overall rate of cyanostar threading. (C) Snapshot overlaying 900 Brownian particles (beads) determined after 5.0 ms of a Brownian dynamics simulation of step 3. Each particle represents a cyanostar macrocycle, which starts at the top of a free energy barrier (red) and diffuses down into the valley on the right (blue). The spread in the location of the particles that are evolved over the same period of time implies the stochasticity in motion at the nanoscale. (D) Location of a macrocycle (represented by a bead) at the end of two representative 5.0-ms BD trajectories of macrocycle-threading. The bottom instance shows the macrocycle in a state closest to threading, that is, reaching the energy minima, while the top instance shows the macrocycle still overcoming the barrier. The multiple threading scenarios illustrate heterogeneity of the threading dynamics and reveal the physical significance of thermal noise in this nanoscale process.

By analogy with dimensionality-reduction schemes applied to biomolecular simulations (44), we test the idea that the three-body problem can be reduced to one that involves computing two of the three variables at a time. We take advantage of the fact that barriers for threading (steps 3 and 5) depend mostly on interactions between ring and thread: threading needs to overcome the sterics of the large pyridine groups on either end of the tetrazine presumably by the reasonably frequent rotations of the cyanostar’s olefins seen previously by molecular dynamics (35) (see Inset to Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, section 5). Similarly, inter-ring interactions contribute minimally to barriers but instead contribute considerably to depths of energy wells; for example, introduction of one vs. two rings on the thread stabilizes the complex and increases the well depth from −40 to −80 kJ⋅mol−1. Thus, a physical description of the rate-determining step for threading (step 3) can be reduced to a one-dimensional problem involving just two bodies at a time. Here, the reaction coordinate is cast in terms of only the ring positions using block diagrams (Fig. 5A). The validity of this simplified coordinate can be tested by comparing rates determined from kinetics/Brownian dynamics simulations to experiment.

Block diagrams were created for each step before kinetics modeling (Fig. 5). One-half of the steps are described best as diffusive (step 1, ring dimerization; steps 2 and 4, ring–thread association) and others as thermally activated barrier crossings (steps 3 and 5, first and second threading). Diffusive steps involve translating the center of mass of the mobile rings using a one-dimensional random walk, while thermally activated steps are modeled as Brownian motion. Fluctuations in the walk are determined by the diffusion coefficient following the dissipation-fluctuation theorem (45). Details of individual steps are in the SI Appendix, section 7.

Results from Kinetics Simulations.

The kinetics simulations provide estimates of the mean first-passage time, τ, which is defined as the diffusion-dominated movement of ring(s) from point I to J, and generated for all five steps. Here, τ is the inverse of the rate constant, k: τ = k−1. Movement of the ring(s) along the X axis and onto the BPTz– thread (denoted by Cartesian variable x) between points xi and xj is modeled using the following relationship derived by Szabo et al. (3):

| [6] |

Here, the one-dimensional space in x is discretized into points i, i + 1, …, k, …, j, whereas D(xi) and F(xi) represent the diffusion and free energy of the macrocycle at position xi (Fig. 5 A and B). The quantity represents the probability of finding the macrocycle at any point I along the pathway, where I ∈{i,… j}. On a flat free-energy profile, all of the points from I to J are equally probable, and the rate at which point I is visited is D−1 xI2, that is, it depends entirely on the rate of diffusive motion of the ring. However, when the pathway is accompanied by a descent in free energy, the probability increases and the rate of this visit (τ−1) is higher than that defined by diffusion alone, D−1 xI2. Conversely, climbing the free-energy profile reduces the probability of visiting I and slows down macrocycle movement relative to diffusion. Finally, the derivation of the mean first-passage time relation (Eq. 6) assumed Poisson-distributed statistics (3) of passage times. Consequently, successful transitions between endpoints occurs in 63% of the trajectories (1 − et/τ = 0.63) at time t = τ. The applicability of Eq. 6 to threading is justified in SI Appendix, section 1.2.

We assume the cyanostar’s diffusion coefficient, D, is independent of location on the thread, as has been demonstrated for other molecular machines, but that it depends on the intercyanostar distance. Thus, for steps 1, 3, 4, and 5, D = 7.4 × 10−6 cm2/s represents a monomeric cyanostar (36), and for step 2, D = 6.8 × 10−6 cm2/s represents a dimeric cyanostar (33, 34).

A kinetics model of threading was made by combining experimentally determined free-energy profiles (Fig. 5A) with diffusion coefficients according to Eq. 6. The resulting kinetics model (Fig. 5B) for the inchworm mechanism provides the mean first-passage time for each step: step 1 (dimerization), 22 ns; step 2 (diffusion–association), 40 ns; step 3 (first threading), 0.28 ms; step 4 (association), 44 ns; and step 5 (second threading), 4.6 μs. In addition to barrier-crossing events, step 1 also involves a diffusive search over a distance of 10 Å until the two rings dimerize. For step 1, the actual distance is estimated from the concentration (1 mM) to be ∼700 Å. Diffusion across this distance before dimerization takes an additional 6.4 μs (SI Appendix). Overall, step 3 dominates kinetics, and the entire process occurs on the submillisecond timescale. This timescale is consistent with the kinetics for the rate-limiting step obtained by electrochemistry, k3,expt = 7,000 ± 1,000 s−1, or τ3,expt = 0.12 ms.

A similar kinetic description for the stepwise mechanism seen with cyanodimer is accomplished employing a four-step pathway (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Step 1 involves diffusion–association of the first macrocycle (80 ns). Step 2 describes the first threading (24 ms). Similar to step 1, step 3 also requires 80 ns. Finally, step 4 describing threading of the second macrocycle takes 703 ms. A kinetic barrier of 57 kJ⋅mol−1 is attributed to step 2 and +59 kJ⋅mol−1 in step 4 based on digital simulations of the CVs.

Brownian Dynamics Simulations of Rate-Limiting Step of the Inchworm Model.

In the inchworm’s kinetic model, threading of first and second cyanostars involve crossing energetic barriers. Direct observation of such crossing events is often computationally intractable for barriers beyond 10 kBT (∼25 kJ⋅mol−1). Addressing this issue, Brownian dynamics simulations provide complementary estimates of mean first-passage times, τ, as a means of corroborating results from kinetics simulations, as well as imparting insights on the macrocycle motion underlying the rate-determining steps. We combine Brownian dynamics with the principle of detailed balance along a transition pathway (46) to obtain threading rates but employing modest computational resources (47) (SI Appendix, General Methods and Synthesis). An advantage of this approach is direct observation of individual cyanostar motions modeled as coarse-grained beads (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) representing movements along a free-energy landscape (Movie S1). As expected of Brownian diffusion, these trajectories illustrate heterogeneity in threading dynamics (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) and help reveal the physical significance of thermal motions on the nanoscale (Movie S2). In qualitative agreement with kinetics simulations, we observed times for crossing barriers in steps 1–5 are, in order, 100 ns, 190 ns, 5.6 ms, 200 ns, and 5.9 µs.

Conclusions

The classical three-body problem has been examined using a molecular switch composed of two rings threading onto a rod. Experimental characterization provides a basis to evaluate a simplification of the problem. The two rings are shown to thread in a rare inchworm manner onto a rod when coupled together by noncovalent bonds. This pathway of motion was verified using control compounds: one that only threads by the inchworm pathway and another by the alternative stepwise pathway. Mechanistic models that reproduce electrochemistry data support this conclusion. While this is a formal three-body problem on account of coupling between all components, the theoretical treatment offered by kinetics simulations and Brownian dynamics successfully reduced the complexity of the kinetics to a one-dimensional system governed by ring–thread interactions during barrier crossing. Greater coupling is expected to introduce deviations from this model, which may be handled by more detailed simulations (48) and is expected to reveal novel pathways of motion. Thus, this general approach suggests a means to evaluate designs for three or more coupled bodies capable of undergoing controlled mechanical motion on the molecular scale.

Supporting Information

Supporting information includes SI Appendix (general methods and synthesis, mechanistic models, CV studies, digital simulations of CVs, molecular dynamics, and derivation of kinetics models) and Movies S1–S4 (Movie S1, full movie of the motion depicted in Fig. 5C snapshot; Movies S2–S4, full movies showing the motion of a single particle depicted in Fig. 5D snapshots).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.R.B., E.M.F., Y.L., E.G.S., and A.H.F. acknowledge support from the NSF Grant (CHE 1709909). C.M., A.A., and A.S. acknowledge support from the NIH Center for Macromolecular Modeling and Bioinformatics Grant (P41-GM104601) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) Center for the Physics of Living Cells Grant (PHY-1430124). A.S. acknowledges startup award funds from Arizona State University, NSF Grant (MCB1616590), and NIH Grant (R01-GM067887-11). This research used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which is supported by the Office of Science, US Department of Energy (DE-AC05-00OR22725).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors report a patent awarded on “poly-cyanostilbene macrocycles” that covers the composition of matter of cyanostar macrocycles.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1719539115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Benson CR, Share AI, Flood AH. Bioinspiration and Biomimicry in Chemistry: Reverse-Engineering Nature. Wiley; New York: 2012. Bioinspired molecular machines; pp. 71–119. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks BR, et al. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J Comput Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabo A, Schulten K, Schulten Z. First passage time approach to diffusion controlled reactions. J Chem Phys. 1980;72:4350–4357. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singharoy A, Chipot C, Moradi M, Schulten K. Chemomechanical coupling in hexameric protein-protein interfaces harnesses energy within V-type ATPases. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:293–310. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wickles S, et al. A structural model of the active ribosome-bound membrane protein insertase YidC. eLife. 2014;3:e03035. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maffeo C, Luan B, Aksimentiev A. End-to-end attraction of duplex DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3812–3821. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma W, Schulten K. Mechanism of substrate translocation by a ring-shaped ATPase motor at millisecond resolution. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3031–3040. doi: 10.1021/ja512605w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Y, Chipot C, Cai W, Shao X. Molecular dynamics study of the inclusion of cholesterol into cyclodextrins. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:6372–6378. doi: 10.1021/jp056751a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang F, Guzei IA, Jones JW, Gibson HW. Remarkably improved complexation of a bisparaquat by formation of a pseudocryptand-based [3]pseudorotaxane. Chem Commun (Camb) 2005;2005:1693–1695. doi: 10.1039/b417661h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNitt KA, et al. Reduction of a redox-active ligand drives switching in a Cu(I) pseudorotaxane by a bimolecular mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1305–1313. doi: 10.1021/ja8085593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Share AI, Parimal K, Flood AH. Bilability is defined when one electron is used to switch between concerted and stepwise pathways in Cu(I)-based bistable [2/3]pseudorotaxanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1665–1675. doi: 10.1021/ja908877d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson CR, et al. Extreme stabilization and redox switching of organic anions and radical anions by large-cavity, CH hydrogen-bonding cyanostar macrocycles. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15057–15065. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson CR, Share AI, Marzo MG, Flood AH. Double switching of two rings in palindromic [3]pseudorotaxanes: Cooperativity and mechanism of motion. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:3767–3776. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan T-G, et al. Reversible conversion between a pleated oligo-tetrathiafulvalene radical foldamer and folded donor-acceptor [3]pseudorotaxane under redox conditions. Chem Commun (Camb) 2017;53:5396–5399. doi: 10.1039/c7cc02526b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leigh DA, Wong JKY, Dehez F, Zerbetto F. Unidirectional rotation in a mechanically interlocked molecular rotor. Nature. 2003;424:174–179. doi: 10.1038/nature01758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson MR, et al. An autonomous chemically fuelled small-molecule motor. Nature. 2016;534:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature18013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barendt TA, Ferreira L, Marques I, Félix V, Beer PD. Anion- and solvent-induced rotary dynamics and sensing in a perylene diimide [3]catenane. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:9026–9037. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erbas-Cakmak S, et al. Rotary and linear molecular motors driven by pulses of a chemical fuel. Science. 2017;358:340–343. doi: 10.1126/science.aao1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambron JC, Heitz V, Sauvage J-P. Transition metal templated formation of [2]- and [3]-rotaxanes with porphyrins as stoppers. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:12378–12384. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, et al. Linear artificial molecular muscles. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9745–9759. doi: 10.1021/ja051088p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogoshi T, et al. High-yield diastereoselective synthesis of planar chiral [2]- and [3]rotaxanes constructed from per-ethylated pillar[5]arene and pyridinium derivatives. Chemistry. 2012;18:7493–7500. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokunaga Y, Ikezaki S, Kimura M, Hisada K, Kawasaki T. Five-state molecular switching of a [3]rotaxane in response to weak and strong acid and base stimuli. Chem Commun (Camb) 2013;49:11749–11751. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47343k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng Z, Xiang J-F, Chen C-F. Tristable [n]rotaxanes: From molecular shuttle to molecular cable car. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1520–1525. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witus LS, et al. Relative contractile motion of the rings in a switchable palindromic [3]rotaxane in aqueous solution driven by radical-pairing interactions. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:6089–6093. doi: 10.1039/c4ob01228c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagesar DC, Wiering PG, Kay ER, Leigh DA, Brouwer AM. Successive translocation of the rings in a [3]rotaxane. ChemPhysChem. 2016;17:1902–1912. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201501162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen SS, et al. Mechanistic evaluation of motion in redox-driven rotaxanes reveals longer linkers hasten forward escapes and hinder backward translations. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:6373–6384. doi: 10.1021/ja5013596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baroncini M, Silvi S, Venturi M, Credi A. Reversible photoswitching of rotaxane character and interplay of thermodynamic stability and kinetic lability in a self-assembling ring-axle molecular system. Chemistry. 2010;16:11580–11587. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bottari G, et al. Entropy-driven translational isomerism: A tristable molecular shuttle. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:5886–5889. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng C, et al. An artificial molecular pump. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10:547–553. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee JW, Kim K, Kim K. A kinetically controlled molecular switch based on bistable [2]rotaxane. Chem Commun (Camb) 2001:1042–1043. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panman MR, et al. Operation mechanism of a molecular machine revealed using time-resolved vibrational spectroscopy. Science. 2010;328:1255–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.1187967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Zwaag D, et al. Kinetic analysis as a tool to distinguish pathway complexity in molecular assembly: An unexpected outcome of structures in competition. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:12677–12688. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fatila EM, Twum EB, Karty JA, Flood AH. Ion pairing and co-facial stacking drive high-fidelity bisulfate assembly with cyanostar macrocyclic hosts. Chemistry. 2017;23:10652–10662. doi: 10.1002/chem.201701763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fatila EM, et al. Anions stabilize each other inside macrocyclic hosts. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:14057–14062. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, et al. Flexibility coexists with shape-persistence in cyanostar macrocycles. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:4843–4851. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiao B, Anderson JR, Pink M, Flood AH. Size-matched recognition of large anions by cyanostar macrocycles is saved when solvent-bias is avoided. Chem Commun (Camb) 2016;52:8683–8686. doi: 10.1039/c6cc03463b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singharoy A, et al. Macromolecular crystallography for synthetic abiological molecules: Combining xMDFF and PHENIX for structure determination of cyanostar macrocycles. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8810–8818. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yildiz A, Tomishige M, Vale RD, Selvin PR. Kinesin walks hand-over-hand. Science. 2004;303:676–678. doi: 10.1126/science.1093753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yildiz A, et al. Myosin V walks hand-over-hand: Single fluorophore imaging with 1.5-nm localization. Science. 2003;300:2061–2065. doi: 10.1126/science.1084398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhabha G, Johnson GT, Schroeder CM, Vale RD. How dynein moves along microtubules. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Troshin K, Hartwig JF. Snap deconvolution: An informatics approach to high-throughput discovery of catalytic reactions. Science. 2017;357:175–180. doi: 10.1126/science.aan1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Astumian RD. Design principles for Brownian molecular machines: How to swim in molasses and walk in a hurricane. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:5067–5083. doi: 10.1039/b708995c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith RP. Configurational entropy of polyethylene and other linear polymers. J Polym Sci A. 1966;4:869–880. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zwanzig R. Nonequilibrium Statistical Mechanics. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kubo R. The fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Rep Prog Phys. 1966;29:255. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aird A, Wrachtrup J, Schulten K, Tietz C. Possible pathway for ubiquinone shuttling in Rhodospirillum rubrum revealed by molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys J. 2007;92:23–33. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Comer J, Aksimentiev A. Predicting the DNA sequence dependence of nanopore ion current using atomic-resolution Brownian dynamics. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2012;116:3376–3393. doi: 10.1021/jp210641j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu H, Shao X, Chipot C, Cai W. The lubricating role of water in the shuttling of rotaxanes. Chem Sci. 2017;8:5087–5094. doi: 10.1039/c7sc01593c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.