Significance

The World Health Organization’s target is to stop sleeping sickness transmission by 2030. Current challenges include a shortage of safe, affordable, and efficacious drugs, as well as veterinary reservoirs of trypanosomes, which themselves cause livestock disease. Benzoxaboroles are under development for these lethal diseases and show great promise in clinical and veterinary trials. We developed an optimized genome-scale gain-of-function library in trypanosomes and used it to identify the benzoxaborole target. These drugs bind the active site of CPSF3, an enzyme that processes messenger RNA and facilitates gene expression. Our studies validate the gain-of-function approach and reveal an important drug target. These findings will facilitate development of improved therapies and prediction and monitoring of drug resistance.

Keywords: CPSF73, drug discovery, genetic screening, N-myristoyltransferase, Ysh1

Abstract

African trypanosomes cause lethal and neglected tropical diseases, known as sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in animals. Current therapies are limited, but fortunately, promising therapies are in advanced clinical and veterinary development, including acoziborole (AN5568 or SCYX-7158) and AN11736, respectively. These benzoxaboroles will likely be key to the World Health Organization’s target of disease control by 2030. Their mode of action was previously unknown. We have developed a high-coverage overexpression library and use it here to explore drug mode of action in Trypanosoma brucei. Initially, an inhibitor with a known target was used to select for drug resistance and to test massive parallel library screening and genome-wide mapping; this effectively identified the known target and validated the approach. Subsequently, the overexpression screening approach was used to identify the target of the benzoxaboroles, Cleavage and Polyadenylation Specificity Factor 3 (CPSF3, Tb927.4.1340). We validated the CPSF3 endonuclease as the target, using independent overexpression strains. Knockdown provided genetic validation of CPSF3 as essential, and GFP tagging confirmed the expected nuclear localization. Molecular docking and CRISPR-Cas9-based editing demonstrated how acoziborole can specifically block the active site and mRNA processing by parasite, but not host CPSF3. Thus, our findings provide both genetic and chemical validation for CPSF3 as an important drug target in trypanosomes and reveal inhibition of mRNA maturation as the mode of action of the trypanocidal benzoxaboroles. Understanding the mechanism of action of benzoxaborole-based therapies can assist development of improved therapies, as well as the prediction and monitoring of resistance, if or when it arises.

African trypanosomes are transmitted by tsetse flies and cause devastating and lethal diseases: sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in livestock. The closely related parasites that cause acute and chronic forms of the human disease in Eastern and Western Africa are Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, respectively (1). These parasites also infect other mammals, whereas Trypanosoma congolense, Trypanosoma vivax, and Trypanosoma brucei brucei also cause livestock disease (2). The vast majority of human cases are caused by T. b. gambiense, which progresses from a hemolymphatic first-stage infection to a typically lethal second stage, when parasites enter the central nervous system.

There is no effective vaccine against African trypanosomes. Current drugs against the first-stage disease, pentamidine and suramin, are ineffective if parasites have entered the central nervous system, which is frequently the case at the point of diagnosis. For second-stage disease, the central nervous system-penetrant drugs, melarsoprol or nifurtimox and eflornithine, are required (3). Melarsoprol suffers from significant toxicity and drug resistance, and its use is now limited (4). The current nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (NECT) is effective, but expensive, and administration is complex, requiring hospitalization, trained staff, and multiple drug infusions, which may not be sustainable (5). Drug resistance also threatens the usefulness of current chemotherapy, and chemoprophylaxis for animal trypanosomiasis with diminazene aceturate (Berenil) or isometamidium (Samorin) (2).

Despite the challenges, cases of sleeping sickness have declined in recent years, and the disease is now a World Health Organization (WHO) target for elimination as a public health problem by 2020 (defined as <1 case/10,000 inhabitants in 90% of endemic foci). A further target is to stop disease transmission by 2030 (6). Attainment of these goals likely depends on the success of therapies currently in clinical and veterinary development (3), as it will also be important to control reservoirs in animals (7). Safe, affordable, oral therapies that are effective against both stages of the human disease and effective drugs against the animal disease would be transformative. The former could also remove the need for painful and cumbersome lumbar puncture diagnosis to confirm the second stage of human infection.

At the end of the last century, there were no new drugs in the pipeline. There are now two new and promising oral drugs in clinical trials against sleeping sickness, acoziborole (AN5568 or SCYX-7158) (8, 9) and fexinidazole (10), and one in trials against nagana, AN11736 (11). However, the relevant cellular targets of these drugs remain unknown, hindering further development, exploitation of related molecules, and understanding of toxicity or resistance mechanisms.

Both acoziborole and AN11736 are benzoxaboroles (8, 9, 11). Acoziborole, developed by Anacor and Scynexis, emerged in 2011 as an effective, safe, and orally active preclinical candidate against T. b. gambiense, T. b. rhodesiense, and T. b. brucei, including melarsoprol-resistant strains, and against both disease stages (8, 9). A phase 1 clinical trial was successfully completed in 2015, and a phase 2/3 trial was initiated in 2016 by the Drugs for Neglected diseases initiative (www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/portfolio/scyx-7158/). AN11736 is effective against both T. congolense and T. vivax, shows great promise for the treatment of animal trypanosomiasis in early development studies (11). Another benzoxaborole, AN4169 (SCYX-6759), displays activity against both T. brucei (12) and Trypanosoma cruzi, the South American trypanosome (13, 14), which causes Chagas disease. In addition, the benzoxaborole, DNDI-6148, was recently approved for phase 1 assessment and is a promising candidate for treating both visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania parasites, another group of trypanosomatids (www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/portfolio/oxaborole-dndi-6148/). Related back-up benzoxaboroles are also available if needed.

Oxaboroles display antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, antiprotozoal, and anti-inflammatory activity. Known targets include a viral protease (15), bacterial β-lactamase (16), bacterial leucyl-tRNA synthetase (17), and apicomplexan CPSF3, a metallo β-lactamase (18, 19). Tavaborole (AN2690 or Kerydin) is a topical treatment approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for toenail onychomycosis (20) that targets the fungal cytoplasmic leucyl-tRNA synthetase (21). Oxaboroles are also potential antihypertensive rho-activated kinase inhibitors (22) and anti-inflammatory phosphodiesterase inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis (23). Genomic and proteomic approaches, using oxaborole-1, a close analog of acoziborole, previously yielded lists of candidate genes implicated in the antitrypanosomal mode of action (24), whereas metabolomic analysis after acoziborole exposure indicated perturbation of S-adenosyl-l-methionine metabolism (25), but the trypanocidal targets of acoziborole and AN11736 remained unknown.

RNA interference library screens have been very effective for identifying drug resistance mechanisms in trypanosomes, particularly because of defects in drug uptake or metabolism (26), but this loss-of-function approach does not typically reveal the target or targets of a drug. Indeed, RNA interference screens recently revealed a prodrug activation mechanism for a class of aminomethyl-benzoxaboroles, including AN3057, involving a T. b. brucei aldehyde dehydrogenase, but not the target (27). A gain-of-function approach is more likely to identify drug targets, and proof of concept has been achieved using an overexpression library in T. b. brucei (28). However, the use of relatively short inserts (∼1.2 kbp) and fusion with a common RNA-binding domain at the N termini (29) precluded the overexpression of full-length native proteins, many proteins larger than ∼50 kDa, or protein targeting to the secretory pathway or mitochondrion (28). A related overexpression approach with the potential to identify drug targets, Cos-seq, has also been described for Leishmania (30).

We assembled a T. b. brucei inducible overexpression library for full-length genes and with optimized genome coverage. Here, we describe and validate high-throughput overexpression, combined with massive parallel screening, and use the approach to identify the common target of several benzoxaboroles, including acoziborole and AN11736. The trypanocidal benzoxaborole target is the nuclear mRNA processing endonuclease, cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 3 (CPSF3/CPSF73/Ysh1).

Results

A High-Coverage T. b. brucei Overexpression Library.

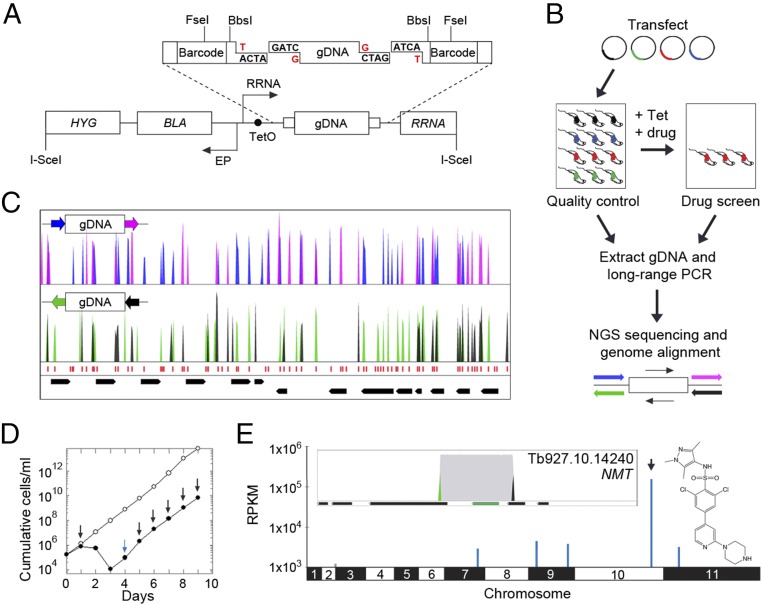

Our goal was to develop an unbiased bloodstream-form T. b. brucei overexpression library with optimized genome coverage. We first assembled the overexpression construct, pRPaOEX, and then constructed a library using T. b. brucei genomic DNA partially digested with Sau3AI (Fig. 1A). The T. b. brucei genome comprises 46% GC content (31), so Sau3AI sites (GATC) occur once every ∼256 bp. The genome has only two known introns (32), such that the vast majority of genes comprise a single protein-coding exon with an average size of 1,592 bp; the core genome is also otherwise compact with average intergenic regions of 1,279 bp (31). Partially digested 3–10-kbp genomic DNA fragments were cloned in pRPaOEX, using a BbsI semifilling strategy to optimize the library assembly step (Fig. 1A); 99.4% of annotated coding sequences are <10 kbp. Our approach places the genomic DNA fragments under the control of a tetracycline-inducible ribosomal RNA (RRNA) promoter (Fig. 1A), an RNA polymerase I promoter that can drive high-level expression of protein coding genes in trypanosomes (33); transcription by RNA polymerase I provides 40-fold stronger transcription than RNA polymerase II, which produces the vast majority of the natural transcriptome (34). The resulting plasmid library comprised >20 million clones, from which 26 (87%) of 30 analyzed contained inserts in the expected size-range (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A).

Fig. 1.

Assembly and validation of the T. b. brucei overexpression library. (A) Schematic illustrating the pRPaOEX construct and library assembly. BLA, blasticidin resistance gene; EP and RRNA arrows, procyclin and RRNA promotors; HYG and RRNA, hygromycin and ribosomal RNA targeting sequences; TetO, Tet operator. Partially Sau3AI-digested gDNA and BbsI-digested pRPaOEX were semifilled (red G’s and T’s). Other relevant restriction sites are shown. (B) The schematic illustrates T. b. brucei library construction, screening, sequencing, and mapping. See SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods and text for further details. Blue/pink or black/green barcodes indicate fragments overexpressed in each direction. (C) A representative 35-kbp genomic region indicates coverage and fragment junctions corresponding to Sau3AI sites (red). Barcoded reads as in B. Black bars, CDSs, and two convergent polycistrons. (D) Growth curves for the induced library with (closed circles) or without (open circles) DDD85646. For the former, arrows indicate the addition of Tet (blue) or Tet + drug (black). (E) Genome-scale map of hits in the DDD85646 screen (structure indicated). The arrowhead and inset box indicate the primary hit, encoding N-myristoyltransferase (NMT, green). Black bars and black/green peaks as in B and C; gray, all mapped reads.

To establish a T. b. brucei library, we used a system for high-efficiency transfection previously used to assemble other libraries in bloodstream-form cells (35). This involves I-SceI meganuclease-mediated induction of a break at the chromosomal integration target site for pRPaOEX. I-SceI was also used to linearize the plasmid library before transfection (Fig. 1A), further facilitating optimal genome coverage (Materials and Methods). The number of T. b. brucei clones recovered was estimated to be ∼1 million, equating to a library with ∼eightfold genome coverage (fourfold in each direction); 17 of 22 T. b. brucei clones analyzed (77%) contained inserts in the expected size range, as determined using a long-range PCR assay (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

The workflow for library construction and screening is illustrated in Fig. 1B. Before screening, we first carried out a quality-control step, both to determine the integrity and coverage of the T. b. brucei library and to establish the screening protocol (Fig. 1B). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from the pooled library and fragments were amplified from the integrated overexpression constructs using long-range PCR, these products were deep-sequenced, and the reads were mapped to the reference genome (Fig. 1B); pRPaOEX-derived barcodes were included to precisely map overexpressed fragments and to determine their orientation. This indicated that >95% of genes are included in the library, and a representative 35-kbp region of the genome reveals excellent coverage, with fragment junctions (barcoded reads) corresponding to the expected locations of Sau3AI sites (Fig. 1C). The barcodes also effectively reveal fragment orientation with respect to the RRNA promoter in the overexpression construct. As expected, half of the fragments are in the forward direction and half are in the reverse direction (Fig. 1C, color coding).

Drug-Target Identification Provides Validation for the Overexpression Library.

Overexpression or gain of function of a drug target can produce drug-resistant cells by increasing the pool of functional protein, possibly by reducing intracellular free drug concentration through binding or through both mechanisms simultaneously. Other resistance mechanisms are also possible (36). In the first instance, we wanted to determine whether our screening approach could identify a known drug target. There are very few inhibitors with known targets in trypanosomes, and therefore we used the well-characterized, experimental N-myristoyltransferase inhibitor, DDD85646 (37). The library was induced with tetracycline for 24 h before selection for 9 d with 5.2 nM DDD85646 (∼2 × EC50, effective concentration of drug to reduce cell growth by 50%). Drug-selected cells displayed the expected reduced growth relative to a nonselected, but induced, control population (Fig. 1D). Because integrated, overexpressed fragments are replicated within T. b. brucei genomic DNA, those that confer resistance will be over-represented after drug selection.

Following the scheme presented here (Fig. 1B), a genome-scale map of hits was generated from the DDD85646 screen (Fig. 1E); the map includes the full nonredundant set of ∼7,500 genes. This screen revealed a single major hit on chromosome 10 (Fig. 1E) comprising >66% of all mapped reads. A closer inspection revealed the barcoded junctions of a 3.982-kbp fragment. This fragment (>2.7 million mapped reads) encompassed one complete protein coding sequence (CDS) (SI Appendix, Table S1) that encodes N-myristoyltransferase (Fig. 1E, Inset; Tb927.10.14240, NMT), the known target of DDD85646 (37). The barcodes (green and black peaks) reveal the orientation of the gene, and indeed, as expected, they show a sense orientation of the coding sequence with respect to the RRNA promoter driving overexpression.

Our approach also presents an opportunity to uncover biology beyond an immediate drug target. In the case of the NMT inhibitor, we asked whether overexpression of essential NMT-substrates would confer drug-resistance. Global profiling revealed 53 high-confidence candidate N-myristoylated proteins in T. brucei (38). Only four additional fragments with intact CDSs registered on the genome-scale map for the DDD85646-screen, and one of these (>54,000 mapped reads) encompassed an array of almost identical genes on chromosome 9 (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Table S1). These genes encode the N-myristoylated ADP ribosylation factor 1 (ARF1), an essential Golgi protein required for endocytosis (39). Notably, both ARF1 knockdown (39) and DDD85646 exposure/NMT-inhibition (37) yield the same endocytosis-defective “BigEye” phenotype (40).

Thus, the results of this screen support the view that DDD85646 is a specific inhibitor of T. b. brucei NMT, and also that ARF1 is a major NMT substrate that contributes to lethality when N-myristoylation, membrane association of the ARF1 protein, and endocytosis, are defective. Taken together, this provides excellent validation for the high-throughput overexpression library and for the genome-wide screening approach.

Screens with Benzoxaboroles Identify CPSF3 as the Probable Target.

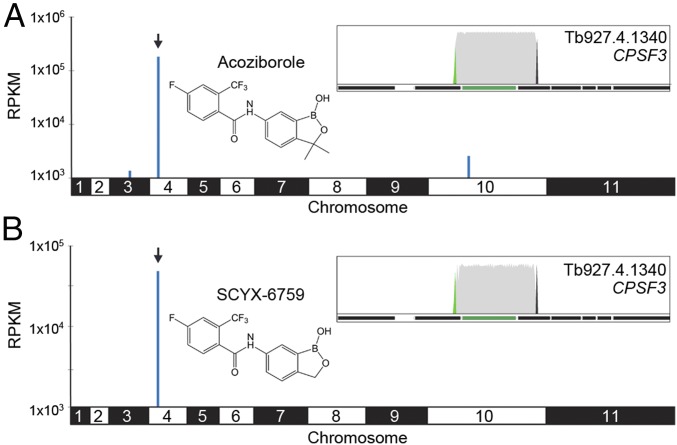

The overexpression library was induced as described here and selected for 8 d with 1 µM acoziborole (∼2 × EC50; SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). Sequencing and mapping of overexpressed inserts revealed another remarkably specific and dominant hit on the genome-scale map; >72% of all reads mapped to a single region on chromosome 4 (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S2; >6.1 million mapped reads). Only one additional fragment that registered on this map encompassed an intact CDS, encoding a hypothetical protein (Tb927.10.5630) on chromosome 10 (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S2), but this fragment registered <1% of the reads mapped to the major hit fragment, and so was not investigated further. Closer inspection of the mapped reads on chromosome 4 revealed a single 4.276-kbp fragment encompassing one complete 2.725-kbp CDS, Tb927.4.1340 (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S2). Tb927.4.1340 encodes a subunit of the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor complex (CPSF3; Fig. 2A, Inset). As earlier, the barcodes reveal the expected sense orientation of the fragment with respect to the promoter.

Fig. 2.

Screens with benzoxaboroles identify CPSF3 as the putative target. (A) Genome-scale map of hits in the acoziborole screen (structure indicated). The arrowhead indicates the primary hit on chromosome 4. (Inset) Primary hit, Tb927.4.1340 (green bar) encoding CPSF3. Other details as in Fig. 1E. (B) Genome-scale map of hits in the SCYX-6759 screen. Other details as in A.

A screen with a second benzoxaborole, AN4169/SCYX-6759, active against both T. brucei (12) and T. cruzi (13, 14), for 8 d at 0.3 µM (∼2 × EC50; SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D), revealed the same major hit as acoziborole, Tb927.4.1340/CPSF3 (Fig. 2B). Once again, this hit was remarkably specific and dominant, with no additional fragments registered on the genome-scale map in this case (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Table S3).

Genetic Validation of CPSF3 as the Target of the Trypanocidal Benzoxaboroles.

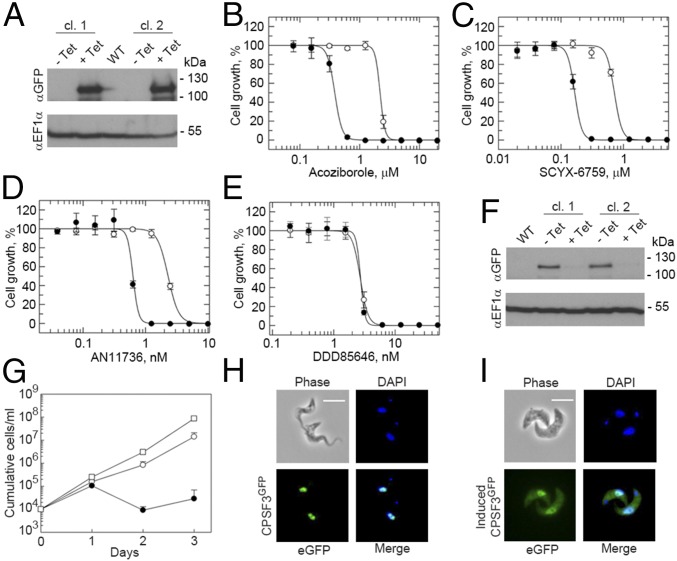

The results presented here suggest acoziborole and SCYX-6759 are specific inhibitors of T. b. brucei CPSF3. To validate this hypothesis, we first generated independent T. b. brucei strains for inducible overexpression of a C-terminal GFP-tagged version of CPSF3; inducible overexpression of CPSF3GFP was confirmed by protein blotting (Fig. 3A). The EC50 values for both acoziborole and SCYX-6759 were determined, revealing that cells induced to overexpress CPSF3GFP displayed 5.7-fold (Fig. 3B) and 4.2-fold resistance (Fig. 3C) relative to uninduced cells, respectively. AN11736 is another benzoxaborole (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) that shows great promise for the treatment of animal African trypanosomiasis (11). We also determined the AN11736 EC50 and found that cells induced to overexpress CPSF3GFP displayed 3.6-fold resistance (Fig. 3D). Thus, CPSF3 is likely the target of both the human and animal trypanocidal benzoxaboroles. Two additional benzoxaboroles (24, 27) (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), and the NMT-inhibitor (37) as a control, were also tested. CPSF3GFP overexpressing cells displayed fourfold resistance to oxaborole-1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B), 2.6-fold resistance to AN3057 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C), and as expected, no resistance to the NMT inhibitor (Fig. 3E). Thus, CPSF3 appears to be the target of all five benzoxaboroles tested: acoziborole, SCYX-6759, AN11736, oxaborole-1, and AN3057.

Fig. 3.

Validation of T. b. brucei CPSF3 as the benzoxaborole target. (A) Inducible overexpression (24 h +tetracycline, Tet) of CPSF3GFP was demonstrated by protein blotting; two independent clones. Dose–response curves with (open circles) and without (closed circles) overexpression of CPSF3GFP for (B) acoziborole: EC50 no Tet, 0.38 ± 0.01 µM; +Tet, 2.19 ± 0.21 µM; 5.7-fold shift; (C) SCYX-6759: EC50 no Tet, 0.17 ± 0.01 µM; +Tet, 0.71 ± 0.04 µM; 4.2-fold shift; (D) AN11736: EC50 no Tet, 0.63 ± 0.03 nM; +Tet, 2.29 ± 0.06 nM; 3.6-fold shift; (E) DDD85646: EC50 no Tet, 2.7 ± 0.05 nM; +Tet, 2.73 ± 0.17 nM. Error bars, ±SD; n = 3. (F) Inducible CPSF3 knockdown (24 h +Tet) was demonstrated by protein blotting; two independent clones. (G) Cumulative cell growth was monitored during CPSF3 knockdown. Wild-type (open squares), no Tet (open circles), +Tet (closed circles); two of the three latter populations display recovery after 3 d, as often seen in similar experiments, resulting from disruption of the RNA interference cassette in some cells. Error bars, ±SD; n = 3 independent knockdown strains. Fluorescence microscopy reveals the subcellular localization of CPSF3GFP in cells expressing (H) a native tagged allele or (I) an overexpressed copy. (Scale bars, 10 µM.)

Inducible RNA interference was used to further genetically validate CPSF3 as a drug target. We suspected that CPSF3 knockdown would result in loss of viability, both because of its role in RNA processing and because our genetic screens indicate that the trypanocidal benzoxaboroles act by specifically targeting CPSF3. In addition, prior genome-wide knockdown profiling indicated that CPSF3 was among only 16% of genes that registered a significant loss of fitness in multiple experiments (41). Inducible knockdown strains were assembled with a GFP-tagged native allele of CPSF3, and inducible knockdown of CPSF3GFP was confirmed by protein blotting (Fig. 3F). We observed a major loss of fitness after CPSF3 knockdown (Fig. 3G). Thus, T. b. brucei CPSF3 function is essential for viability.

The subcellular localization of CPSF3GFP was also examined in cells expressing a native copy of CPSF3GFP (Fig. 3H) or overexpressing CPSF3GFP (Fig. 3I). Consistent with its role in mRNA maturation, we observed the expected nuclear localization for the protein expressed from the native locus (Fig. 3H). In contrast, and consistent with increased expression, we observed a more intense nuclear CPSF3GFP signal and an additional, ectopic, cytoplasmic signal in cells overexpressing the protein (Fig. 3I).

Acoziborole Specifically Blocks the Catalytic Site of Trypanosome CPSF3.

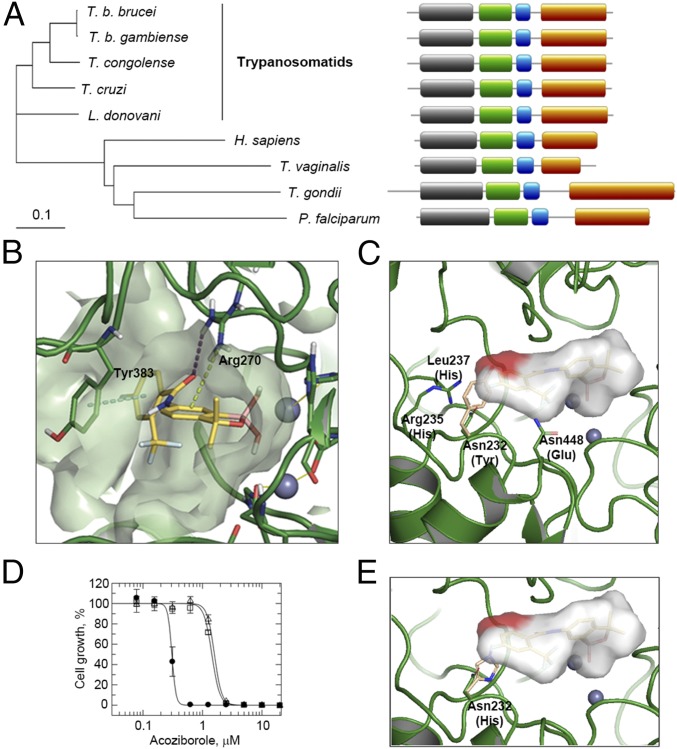

Analysis of CPSF3 sequences (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) revealed that the T. b. brucei and T. b. gambiense proteins have identical metallo-β-lactamase and β-CASP domains, which form the catalytic site, with only two amino acid changes in the C-terminal domain. The livestock trypanosome, T. congolense, also displays a high degree of conservation within the metallo-β-lactamase and β-CASP domains, with only 10 conservative amino acid changes. Phylogeny reveals a cluster of trypanosomatid sequences that is distinct from the human, apicomplexan, and Trichomonas vaginalis sequences (Fig. 4A). This reflects divergence within the eukaryotic lineage, and may also reflect the unusual mechanism of coupled polyadenylation and transsplicing in trypanosomatids (42). Nevertheless, the domain structure of CPSF3 is conserved from trypanosomatids to humans (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Molecular docking and editing of the T. b. brucei CPSF3 active site. (A) The phylogenetic tree shows the relationship among CPSF3 proteins from humans and protozoal parasites, all discussed in the text. (Right) Domain structure for each protein. Domains: gray, metallo-β-lactamase (residues 48–250 in T. brucei); green, β-CASP (residues 271–393 in T. brucei); blue, Zn-dependent metallo-hydrolase (residues 408–463 in T. brucei); rust, C-terminal (residues 502–746 in T. brucei). (B) Docking model for acoziborole (yellow structure) bound to T. brucei CPSF3. Gray spheres, zinc atoms; dotted lines, protein–ligand interactions. (C) Modified docking model illustrating a steric clash between acoziborole (red patch) and a Tyr residue (beige) in human CPSF3, in place of Asn232 in T. brucei CSPF3. The acoziborole molecular surface is otherwise represented in gray. Other binding site residues that differ between the human and T. brucei enzymes are indicated. (D) Dose–response curves with wild-type T. b. brucei (closed circles) or T. b. brucei expressing Asn232His substituted CPSF3 (open squares and triangles, two independent clones). Acoziborole EC50: wild-type, 0.31 ± 0.01 µM; Asn232His, 1.59/1.44 ± 0.04/0.05 µM; 5.1/4.6-fold shift. Error bars, ±SD. (E) Modified docking model illustrating a steric clash between acoziborole (red patch) and the His residue (beige) in Asn232His substituted CPSF3.

To further explore the interactions between the benzoxaboroles and CPSF3, molecular docking studies were carried out (Fig. 4B). A T. brucei CPSF3 homology model was built using the Thermus thermophilus TTHA0252 structure complexed with an RNA substrate analog [PDB: 3IEM (43)] as a template. The catalytic site is located at the interface of the metallo-β-lactamase and β-CASP domains and comprises two zinc atoms coordinated by a network of histidine and aspartic acid residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). In the model, the benzoxaborole moiety occupies the same area as the phosphate of the RNA where the two zinc atoms are present. The boron atom reacts with an activated water molecule located at the bimetal center, leading to a tetrahedral negatively charged species that mimics the transition state of the phosphate of the RNA substrate (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Arg270, which in the template is involved in the recognition of a second phosphate group, extends toward the ligand to establish a hydrogen bond interaction with the amide oxygen and a cation-π interaction with the aromatic six-membered ring of the benzoxaborole. The amide in position 6 of the benzoxaborole ring directs the o-CF3, p-F phenyl ring of acoziborole toward the area occupied by the terminal uracil base of the RNA substrate and establishes a face-to-face π-stacking interaction with Tyr383. The trifluoro methyl group and the fluorine atom on the phenyl ring do not appear to establish a specific interaction.

The proposed mode of binding is consistent with the established structure–activity relationships for this series (8, 9); specifically, the boron atom in the heterocyclic core is essential for trypanocidal activity, and variation on the five-membered ring of the benzoxaborole had a pronounced (>10-fold) effect, whereas variation on the phenyl ring distal to the benzoxaborole core had relatively little effect. The o-CF3 and p-F, however, provide a favorable pharmacokinetic/dynamic profile that results in an optimal response in the trypanosomiasis in vivo model. The docking model is also consistent with structural data available for other bimetal systems, such as benzoxaboroles binding to phosphodiesterase 4 (23), cyclic boronate binding to β-lactamases (44), and the mechanism of action proposed for other RNA degrading proteins of the metallo-β-lactamase family (43). Thus, the proposed mode of acoziborole binding indicates a steric block at the active site of trypanosome CPSF3 that perturbs the pre-mRNA endonuclease activity.

Finally, we asked why acoziborole is well tolerated in animal models and in humans, given the similarity between T. brucei CPSF3 and human CPSF3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). There are 26 residues within 5 Å of acoziborole in the model shown in Fig. 4B (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), and only four of these residues differ between the T. brucei and human enzymes (Fig. 4C); all 26 residues are conserved among the trypanosomatids. The bulky Tyr side-chain in the human enzyme, in place of Asn232, in particular, presents a steric clash with the o-CF3, p-F phenyl moiety of acoziborole (Fig. 4C). A Tyr residue is also present at this position in the apicomplexan sequences, whereas a His residue with a bulky side-chain is present at this position in the T. vaginalis sequence (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). A clash with acoziborole in this position would likely prevent binding or disrupt the geometry required for covalent bond formation. This hypothesis was explored using CRISPR-Cas9-based editing (45) to mutate T. b. brucei CPSF Asn232. The results suggested that an Asn232Tyr edit was not tolerated, but we found that T. b. brucei expressing an Asn232His substituted form of CPSF3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) were fivefold resistant to acoziborole (Fig. 4D). As expected, a His residue in place of Asn232 in our docking model, similar to the Tyr residue in the human enzyme, presents a steric clash with acoziborole (Fig. 4E). Thus, specific structural differences between trypanosome and host CPSF3 offer an explanation for the safety profile and selective activity of acoziborole.

Discussion

Phenotypic screening is a powerful strategy in drug discovery that yields many anti-infective lead compounds for potential development. The targets and mode of action of those compounds typically remain unknown, however. Although clinical development is possible without this knowledge, it is nonetheless highly desirable and can facilitate further optimization of therapeutics, as well as the prediction and monitoring of drug resistance.

Genomic and proteomic studies previously yielded a list of genes implicated in the mode of action of oxaborole-1; this list included CPSF3 and an adjacent glyoxalase, amplified in the genome in one of three resistant clones, but no candidate was identified using both approaches, and the list of candidates was too extensive for a systematic appraisal (24). Our results now support an interaction between oxaborole-1 and CPSF3. CPSF3 orthologs were also recently identified as targets of another benzoxaborole (AN3661) active against the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum (19), and Toxoplasma gondii (18). Thus, CPSF3 is a common target of benzoxaboroles in the phylogenetically distant Apicomplexa and trypanosomatids. Our identification of T. brucei CPSF3 as the target of several benzoxaboroles now suggests that CPSF3 is also likely to be a promising drug target, and the target of benzoxaboroles in other protozoal parasites, including the other trypanosomatids, T. cruzi and Leishmania spp; all CPSF3 catalytic site residues are identical among these trypanosomatid sequences and the T. brucei sequence (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A).

The metazoan CPSF complex recognizes polyadenylation sites and controls pre-mRNA cleavage, polyadenylation, and transcription termination (46); the CPSF3 component is the 3′ end processing endonuclease (47). Notably, the complex is unlikely to couple polyadenylation to transcription termination in trypanosomatids, as transcription is almost exclusively polycistronic in these cells (48). Polyadenylation and trans-splicing of adjacent genes are coupled in trypanosomatids, however (42), and consistent with this, CPSF3 knockdown disrupted both polyadenylation and trans-splicing in T. b. brucei (49). Accordingly, inhibition of CPSF3 may explain perturbed methyl-donor metabolism after acoziborole exposure (25), which may be because of reduced mRNA methylation as a result of a splicing defect. CPSF3 also associates with the U1A snRNP splicing complex in trypanosomatids (50).

Molecular docking studies and evidence from the Asn232His mutant indicate how benzoxaboroles occupy the T. brucei CPSF3 active site, blocking pre-mRNA endonuclease activity. The presence of a bulky Tyr side-chain in the human CPSF3 suggests a steric clash with acoziborole, providing an explanation for the selective activity and safety profile. Thus, our findings indicate that the trypanocidal activities of acoziborole and AN11736 are a result of specific perturbation of the polyadenylation and trans-splicing activities directed by trypanosome CPSF3.

Unbiased genetic screens are remarkably powerful and can sample thousands of genes for specific phenotypes. We assembled a T. b. brucei overexpression library with optimized genome coverage. Massive parallel screens confirmed the mode of action of a known NMT inhibitor as inhibition of endocytosis and revealed the mode of action of the benzoxaboroles as inhibition of pre-mRNA maturation. CPSF3 can now be considered genetically and chemically validated as an important antitrypanosomal drug target. Thus, our studies indicate that both clinical and veterinary benzoxaboroles kill trypanosomes by specifically inhibiting the parasite mRNA processing endonuclease, CPSF3.

Materials and Methods

For details of T. brucei growth and manipulation, pRPaOEX plasmid library assembly, T. brucei library assembly, overexpression screening, next generation sequencing data analysis, plasmid construction, EC50 assays, Western blotting, microscopy, docking studies and Cas9-based editing, see SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Zhang, A. Fairlamb, S. Patterson, P. Wyatt, and M. De Rycker for providing samples of antitrypanosomal compounds and S. Hutchinson for advice on sequence mapping. This work was supported by Senior Investigator Award 100320/Z/12/Z (to D.H.), Strategic Award 105021/Z/14/Z, and Centre Award 203134/Z/16/Z, all from the Wellcome Trust; it was also supported by UK Medical Research Council Award MR/K008749/1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. F.N.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: Illumina sequencing data reported in this paper have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena [accession nos.: PRJEB25882 (DDD85646 screen), PRJEB25884 (acoziborole screen), and PRJEB25885 (SCYX-6759 screen)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1807915115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Field MC, et al. Anti-trypanosomatid drug discovery: An ongoing challenge and a continuing need. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:217–231. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giordani F, Morrison LJ, Rowan TG, DE Koning HP, Barrett MP. The animal trypanosomiases and their chemotherapy: A review. Parasitology. 2016;143:1862–1889. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016001268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eperon G, et al. Treatment options for second-stage gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:1407–1417. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.959496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairlamb AH, Horn D. Melarsoprol resistance in African trypanosomiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simarro PP, Franco J, Diarra A, Postigo JA, Jannin J. Update on field use of the available drugs for the chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitology. 2012;139:842–846. doi: 10.1017/S0031182012000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simarro PP, et al. Monitoring the progress towards the elimination of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Büscher P, et al. Informal Expert Group on Gambiense HAT Reservoirs Do cryptic reservoirs threaten gambiense-sleeping sickness elimination? Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs RT, et al. SCYX-7158, an orally-active benzoxaborole for the treatment of stage 2 human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs RT, et al. Benzoxaboroles: A new class of potential drugs for human African trypanosomiasis. Future Med Chem. 2011;3:1259–1278. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mesu VKBK, et al. Oral fexinidazole for late-stage African Trypanosoma brucei gambiense trypanosomiasis: A pivotal multicentre, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:144–154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32758-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akama T, et al. Identification of a 4-fluorobenzyl l-valinate amide benzoxaborole (AN11736) as a potential development candidate for the treatment of animal African trypanosomiasis (AAT) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nare B, et al. Discovery of novel orally bioavailable oxaborole 6-carboxamides that demonstrate cure in a murine model of late-stage central nervous system African trypanosomiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4379–4388. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00498-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bustamante JM, Craft JM, Crowe BD, Ketchie SA, Tarleton RL. New, combined, and reduced dosing treatment protocols cure Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:150–162. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moraes CB, et al. Nitroheterocyclic compounds are more efficacious than CYP51 inhibitors against Trypanosoma cruzi: Implications for Chagas disease drug discovery and development. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4703. doi: 10.1038/srep04703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, et al. Synthesis and SAR of acyclic HCV NS3 protease inhibitors with novel P4-benzoxaborole moieties. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2048–2054. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia Y, et al. Synthesis and SAR of novel benzoxaboroles as a new class of β-lactamase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2533–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez V, et al. Discovery of a novel class of boron-based antibacterials with activity against gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1394–1403. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02058-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palencia A, et al. Targeting Toxoplasma gondii CPSF3 as a new approach to control toxoplasmosis. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:385–394. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201607370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonoiki E, et al. A potent antimalarial benzoxaborole targets a Plasmodium falciparum cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor homologue. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14574. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta AK, Versteeg SG. Tavaborole: A treatment for onychomycosis of the toenails. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9:1145–1152. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2016.1206467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rock FL, et al. An antifungal agent inhibits an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by trapping tRNA in the editing site. Science. 2007;316:1759–1761. doi: 10.1126/science.1142189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akama T, et al. Linking phenotype to kinase: Identification of a novel benzoxaborole hinge-binding motif for kinase inhibition and development of high-potency rho kinase inhibitors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;347:615–625. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.207662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freund YR, et al. Boron-based phosphodiesterase inhibitors show novel binding of boron to PDE4 bimetal center. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3410–3414. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones DC, et al. Genomic and proteomic studies on the mode of action of oxaboroles against the African trypanosome. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steketee PC, et al. Benzoxaborole treatment perturbs S-adenosyl-L-methionine metabolism in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsford S, et al. High-throughput decoding of antitrypanosomal drug efficacy and resistance. Nature. 2012;482:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang N, et al. Host-parasite co-metabolic activation of antitrypanosomal aminomethyl-benzoxaboroles. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1006850. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Begolo D, Erben E, Clayton C. Drug target identification using a trypanosome overexpression library. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:6260–6264. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03338-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erben ED, Fadda A, Lueong S, Hoheisel JD, Clayton C. A genome-wide tethering screen reveals novel potential post-transcriptional regulators in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004178. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gazanion É, Fernández-Prada C, Papadopoulou B, Leprohon P, Ouellette M. Cos-Seq for high-throughput identification of drug target and resistance mechanisms in the protozoan parasite Leishmania. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3012–E3021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520693113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berriman M, et al. The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science. 2005;309:416–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1112642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mair G, et al. A new twist in trypanosome RNA metabolism: cis-splicing of pre-mRNA. RNA. 2000;6:163–169. doi: 10.1017/s135583820099229x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alsford S, Kawahara T, Glover L, Horn D. Tagging a T. brucei RRNA locus improves stable transfection efficiency and circumvents inducible expression position effects. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;144:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wirtz E, Clayton C. Inducible gene expression in trypanosomes mediated by a prokaryotic repressor. Science. 1995;268:1179–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.7761835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glover L, et al. Genome-scale RNAi screens for high-throughput phenotyping in bloodstream-form African trypanosomes. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:106–133. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horn D, Duraisingh MT. Antiparasitic chemotherapy: From genomes to mechanisms. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;54:71–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frearson JA, et al. N-myristoyltransferase inhibitors as new leads to treat sleeping sickness. Nature. 2010;464:728–732. doi: 10.1038/nature08893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright MH, Paape D, Price HP, Smith DF, Tate EW. Global profiling and inhibition of protein lipidation in vector and host stages of the sleeping sickness parasite Trypanosoma brucei. ACS Infect Dis. 2016;2:427–441. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price HP, Stark M, Smith DF. Trypanosoma brucei ARF1 plays a central role in endocytosis and Golgi-lysosome trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:864–873. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen CL, Goulding D, Field MC. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is essential in Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 2003;22:4991–5002. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alsford S, et al. High-throughput phenotyping using parallel sequencing of RNA interference targets in the African trypanosome. Genome Res. 2011;21:915–924. doi: 10.1101/gr.115089.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matthews KR, Tschudi C, Ullu E. A common pyrimidine-rich motif governs trans-splicing and polyadenylation of tubulin polycistronic pre-mRNA in trypanosomes. Genes Dev. 1994;8:491–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishikawa H, Nakagawa N, Kuramitsu S, Masui R. Crystal structure of TTHA0252 from Thermus thermophilus HB8, a RNA degradation protein of the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily. J Biochem. 2006;140:535–542. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brem J, et al. Structural basis of metallo-β-lactamase, serine-β-lactamase and penicillin-binding protein inhibition by cyclic boronates. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12406. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rico E, Jeacock L, Kovářová J, Horn D. Inducible high-efficiency CRISPR-Cas9-targeted gene editing and precision base editing in African trypanosomes. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7960. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26303-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casañal A, et al. Architecture of eukaryotic mRNA 3′-end processing machinery. Science. 2017;358:1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.aao6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandel CR, et al. Polyadenylation factor CPSF-73 is the pre-mRNA 3′-end-processing endonuclease. Nature. 2006;444:953–956. doi: 10.1038/nature05363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clayton CE. Gene expression in kinetoplastids. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;32:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koch H, Raabe M, Urlaub H, Bindereif A, Preußer C. The polyadenylation complex of Trypanosoma brucei: Characterization of the functional poly(A) polymerase. RNA Biol. 2016;13:221–231. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2015.1130208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tkacz ID, et al. Analysis of spliceosomal proteins in trypanosomatids reveals novel functions in mRNA processing. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27982–27999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.095349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.