Significance

We investigate whether American citizens can be persuaded to adopt more inclusionary behavior toward refugees by using a minimally invasive online perspective-taking exercise frequently used by refugee advocates in the real world. Through the use of a randomized survey experiment on a representative sample of American citizens, we find that this short and interactive perspective-taking exercise can promote, in the short term, Americans’ willingness to act on behalf of Syrian refugees, by writing anonymous letters of support to the White House. This effect, while driven primarily by self-identified Democrats, is also apparent among self-identified Republicans.

Keywords: refugees, immigration, exclusion, empathy, perspective taking

Abstract

Social scientists have shown how easily individuals are moved to exclude outgroup members. Can we foster inclusion instead? This study leverages one of the most significant humanitarian crises of our time to test whether, and under what conditions, American citizens adopt more inclusionary behavior toward Syrian refugees. We conduct a nationally representative survey of over 5,000 American citizens in the weeks leading up to the 2016 presidential election and experimentally test whether a perspective-taking exercise increases inclusionary behavior in the form of an anonymous letter supportive of refugees to be sent to the 45th President of the United States. Our results indicate that the perspective-taking message increases the likelihood of writing such a positive letter by two to five percentage points. By contrast, an informational message had no significant effect on letter writing. The effect of the perspective-taking exercise occurs in the short run only, manifests as a behavioral rather than an attitudinal response, and is strongest among Democrats. However, this effect also appears in the subset of Republican respondents, suggesting that efforts to promote perspective taking may move to action a wide cross-section of individuals.

Recent years have seen the highest levels of forced displacement recorded in history. In 2016, 22.5 million people were registered refugees and of these, half were children (1). Nearly one-quarter of all refugees, 5.5 million, were Syrian, making the protracted war in Syria one of the most severe humanitarian crises of our time. At the same time, antirefugee sentiment, often tied to anti-Muslim sentiment, has emerged in some of the wealthiest potential host countries, particularly in Western Europe (2, 3) and the United States (4). Further, there are growing partisan divides regarding attitudes toward immigrants in the United States, driven primarily by increasingly negative attitudes among Republicans (5).

Social scientists have shown how easily humans are moved to exclude outgroup members, including immigrants (6–8) and refugees (3, 9). Violence against immigrants in Europe occurs against a backdrop of economic competition (10), while threats to one’s cultural identity—in the form of religious or linguistic difference, for example refs. 7 and 8—can foster antiimmigrant sentiment even among individuals who hold relatively inclusionary attitudes (11).

In light of increasing political polarization and a widening partisan gap with respect to immigration policy specifically (12), it is worth asking whether this exclusionary trend is inevitable. Yet social scientists have only recently begun to experimentally test outside the laboratory, interventions that counter the outgroup prejudice and exclusionary attitudes they have so rigorously documented in the laboratory (13).

These recent interventions, conducted across a variety of contexts, have yielded promising results. For example, in the United States, a short face-to-face conversation about transgender (trans) rights and discrimination against trans people moves individuals toward more inclusionary attitudes toward trans rights (14). In Japan, an information campaign was effective in increasing inclusionary attitudes toward hypothetical immigrants (15). In Rwanda, a country well known for the 1994 genocide that resulted in the deaths of nearly 1 million people, a radio campaign with messages about reducing intergroup prejudice and violence affected listeners’ perceived social norms and behavior on a variety of dimensions, from intermarriage to cooperation (16). And in Hungary, an online perspective-taking game significantly and durably reduced outgroup prejudice (17).

Our study contributes to this burgeoning literature on prejudice reduction outside the laboratory with a nationally representative survey experiment of 5,400 adult American citizens that tests the effectiveness of a perspective-taking message on inclusionary behavior toward Syrian refugees in the United States. Contrary to the studies listed above, ours tests the effectiveness of a minimally intrusive intervention, one that is already being used by nongovernmental organizations with the goal of shaping public opinion toward refugees: a written exercise in which respondents answer a set of questions while imagining themselves in the shoes of a refugee. This exercise is designed to encourage perspective taking. Numerous interventions examined in the psychology literature are grounded in the idea that perspective taking may reduce prejudice and ingroup bias (18–20). For example, subjects randomly assigned to a treatment condition in which they were asked to “go through the day as if you were an [outgroup member], walking through the world in their shoes and looking at the world through their eyes,” experienced a reduction in bias in evaluating traits of outgroup members (21). Observational work also suggests that differing levels of empathy explain varying political attitudes across racial groups (22, 23). There is therefore a scientific basis for the idea that a perspective-taking treatment may result in more inclusionary attitudes toward refugees. But we currently lack a causal empirical test confirming whether or not this is indeed the case outside the laboratory. Further, we do not know the extent to which perspective taking can shift actual political behavior.

Our approach is to embed an intervention already used by refugee advocates in a nationally representative survey experiment, in which we can causally identify whether and the extent to which the perspective-taking exercise moves individual behavior toward greater refugee inclusion. We find that it does in the short run. Specifically, compared with the control group, those who participated in the perspective-taking exercise were substantially and significantly more likely to write a letter in support of refugees to the US President. Additionally, while the effect of the exercise is strongest for Democrats, a subset of the population with positive priors about refugees, we nonetheless find a smaller, although still significant effect of the intervention among Republican respondents.

Our finding comes with two important caveats. First, while the effect of the intervention is robust and survives the Bonferroni correction for multiple-hypothesis testing, it is also short-lived. After 1 wk, those who participated in the exercise were not more likely than those who had not to write a letter. Second, the effect manifests as a change in respondent behavior, but we find no evidence that it promotes inclusionary attitudes toward refugees. Instead, the evidence suggests that this perspective-taking treatment nudged those with high baseline levels of inclusionary attitudes to act on that preference, closing the attitudinal–behavioral gap in the short term.

Our findings speak to literature across multiple disciplines in the social sciences. First, we contribute to a nascent scholarship on prejudice reduction outside the laboratory. While much existing work has primarily examined attitudes toward and beliefs about outgroup members (14, 17), a main outcome of interest in our study is semibehavioral—the act of writing a letter to an elected leader, a form of political participation. Additionally, although we deliver our intervention in a survey, the intervention itself is one already used by refugee advocates. As such, our experimental treatment reflects ongoing efforts in the real world to promote inclusion toward refugees among host populations.

We also contribute to a rich literature on immigrant exclusion, which often treats individual attitudes and behaviors toward immigrants as static (24). Previous work has emphasized the stability and intensity of immigration attitudes (25). Our study shows that, such research notwithstanding, it is possible to shift a respondent’s behavior toward refugees at least in the short run. Indeed, we show both that a minimally intrusive intervention can change behavior and that this effect is especially strong among those who hold more inclusionary baseline attitudes. These results call for more research on the drivers of attitudinal and behavioral change when it comes to public attitudes toward immigrants and refugees.

Finally, our work has implications for political activists seeking to redirect public debate on refugees. Indeed, the treatments we used in this study reflect the arguments and strategies regularly used in the policy world and in the media, often with the intent to shape public opinion about refugees. Our perspective-taking treatment borrowed directly from an existing lesson builder offered to educators by the Pulitzer Center, an award-winning nonprofit organization “dedicated to supporting in-depth engagement with underreported global affairs through [our] sponsorship of quality international journalism across all media platforms and a unique program of outreach and education to schools and universities” (pulitzercenter.org/about-us). This type of exercise, encouraging people to imagine life as a refugee, is a strategy used by such organizations as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Mercy Corps,* as well as by news organizations such as the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). [The BBC created an interactive page inviting users to “Choose your own escape route” from the Syrian crisis (www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-32057601).] Our results can thus better inform ongoing and future efforts to promote inclusiveness and reduce prejudice toward vulnerable groups.

Research Design

In the 2 wk leading up to the 2016 US presidential election, we fielded a survey experiment on a nationally representative sample of 5,400 American adult citizens. Our research design is presented in SI Appendix, Fig. S1.

We randomly assigned respondents to one of three possible conditions: perspective taking, information, and control. The perspective-taking treatment assigns respondents to a vignette drawn from the Pulitzer Center, asking participants to imagine themselves as a refugee and answer a set of three open-ended questions: “Imagine that you are a refugee fleeing persecution in a war-torn country. What would you take with you, limited only to what you can carry yourself, on your journey? Where would you flee to or would you stay in your home country? What do you feel would be the biggest challenge for you?”

In addition to a pure control condition, we include a separate treatment that provides information about the US commitment to resettling Syrian refugees relative to that of other industrialized democracies. Indeed, at least two previous studies (15, 26) suggest that providing information about immigrants can increase inclusion. More specifically, this treatment provides information in the form of a graph highlighting the comparatively low number of Syrian refugees the United States has committed to resettle (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The treatment provides objective information; it does not engage the respondent in any perspective-taking exercise. We therefore treat it here as a test of whether an alternative message—one that does not appeal to respondent perspective taking—might have an inclusionary effect.

In each of our three conditions, half of the sample was randomly selected to complete the full survey during wave 1, from October 20, 2016 to October 26, 2016. The other half completed only the first part of the survey during wave 1 (completing only the pretreatment and treatment portions) and then completed the second part of the survey (the posttreatment portion) during wave 2, from October 28, 2016 to November 5, 2016. In other words, some respondents were randomly assigned to answer our outcome variable questions immediately after treatment, while others were randomly assigned to do so 8 d later, allowing us to test the durability of our perspective-taking treatment effect.

Our perspective-taking treatment engaged respondents as expected. More than 86% of respondents in the perspective-taking treatment group provided written responses to the perspective-taking vignette questions. We can further confirm that our information treatment provided new information to close to 62% of respondents.

We measure inclusion via a semibehavioral task that asks respondents to write, if they are willing, a letter to the next President of the United States in support of admitting Syrian refugees. An increasing number of social scientists have recently turned to semibehavioral measures in surveys to guard against response bias (27, 28). Indeed, our participants had to write a response requiring both time and cognitive effort. Additionally, the content of the note was meaningful since we told respondents, truthfully, that we would subsequently send the letter to the future President. (For ethical purposes, the letters remain anonymous, and respondents were informed as such.) Relying on such a measure therefore reduces the likelihood that respondents reacted to the perspective-taking intervention out of acquiescence or social desirability bias.

We use a dichotomous measure that equals 1 if the respondent not only said “yes, I want to write a letter,” but actually went on to enter meaningful text in support of refugees. Forty-three percent of all respondents indicated that they wanted to write a letter. Of these, a minority in fact took the opportunity to write a letter critical of refugees. We thus coded each message as being supportive or not based not just on the fact that respondents answered “yes, I want to write a letter,” but also on the actual content of the letter. SI Appendix, Table S2 provides some examples of messages. To be measured as supportive, a letter could not include any discriminatory content toward particular identity groups (Muslims, men, etc.) but could include requests to accept refugees conditional on vetting. In SI Appendix, section 8, we present results on alternative outcome variables, but our main analysis relies on the behavioral measure we prespecified in our preanalysis plan. (We did not prespecify that we would manually recode this variable because we did not anticipate that respondents would take this opportunity to write a negative message to the President (one more excluding of refugees). In our preanalysis plan, we assumed that this variable would capture a behavioral measure of support for refugees. Our recoding reflects the original intent behind the measure.)

Given the randomized design of the experiment, we can rely primarily on ordinary least-squares (OLS) regressions of treatments with appropriate covariate controls on the outcomes to identify our causal estimands of interest. We include controls for the following prespecified pretreatment covariates, measured for each respondent: gender, age (via birth year), US born, education level, religion, party identification (party ID), and ethnocentrism. We use the demeaning construction for noncategorical covariate controls as well as interactions with the treatment in estimating equations (29). Given the goal of identifying the treatment effect of treatment on outcome and controlling for pretreatment covariate , the estimating equation is

| [1] |

where is the estimated treatment effect, and errors are robust and clustered at the individual level for outcomes measured several times for each individual (e.g., refugee rating). While our randomized research design allows for an unbiased estimation of the treatment effect, we wish to improve precision, through the adjustment of covariates (29) as well as the appropriate clustering of errors. We note that our main findings are unchanged when using weighted least squares (SI Appendix, Table S1).

Results

All tests of average treatment effects presented here, unless otherwise noted, have been prespecified in a preanalysis plan we registered with the Evidence on Governance and Politics site (egap.org/registration/2235) before data analysis. The tests on heterogenous treatment effects by respondent party ID were not prespecified.

We find that the perspective-taking treatment resulted in a significant increase in the likelihood of writing a letter in support of refugees. This effect is strongest among Democrats, but observable also among Republicans. Finally, the effect does not survive after 1 wk nor does it appear to change respondent attitudes toward refugees, suggesting that minimally intrusive treatments—like the one used by the Pulitzer Center—are effective in moving inclusionary behavior in the short term and may be more effective in nudging behavioral change than altering attitudes.†

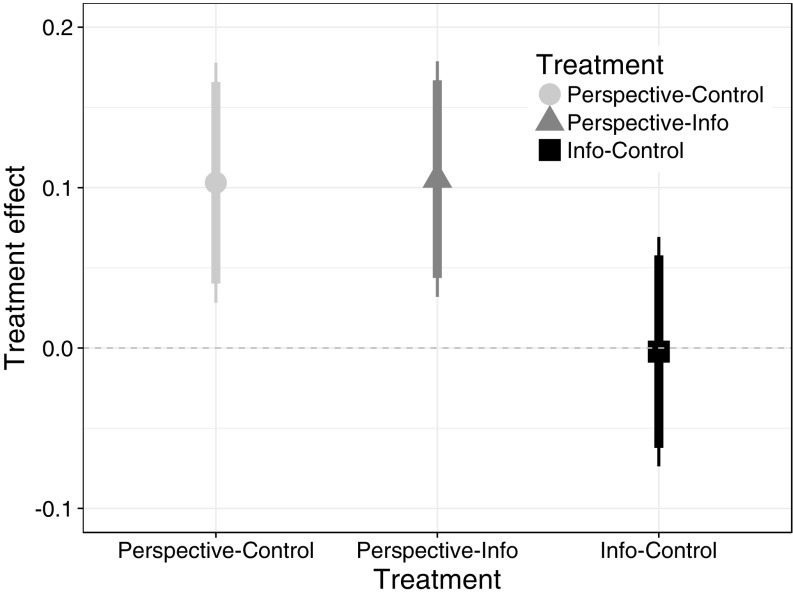

The leftmost coefficient in Fig. 1 illustrates our main finding, that those who were randomly assigned to the perspective-taking treatment were significantly more likely to write a letter in support of refugees than those in the control group. While 18.8% of our sample wrote a supportive letter in the control condition, 20.8% did so under the perspective-taking treatment, an 11% increase. To contextualize the size of the effect, the most popular online petitions to Presidents Obama and Trump to increase US commitments to accept refugees target between 75,000 and 100,000 signatures. (See for example the most popular Change.org and Moveon.org petitions: https://www.change.org/p/barack-obama-resettle-syrian-refugees-in-the-u-s and https://petitions.moveon.org/sign/urge-the-us-government.) An increase from 18.8% of this goal to 20.8% of this goal amounts to an increase in approximately 1,500–2,000 signatures.

Fig. 1.

Average treatment effect of perspective taking relative to the control condition (left) and the information condition (center) and average treatment effect of information relative to control condition (right). Bars show 90% and 95% confidence intervals. Full sample is shown. Average treatment effects are based on an OLS regression estimating Eq. 1.

Fig. 1 further indicates that the effect is not driven by the administration of just any message about Syrian refugees. Indeed, the information message about the number of Syrian refugees the United States has committed to resettling relative to that of other industrialized democracies exercised a statistically insignificant effect on letter writing (rightmost coefficient in Fig. 1). Additionally, the effect of the perspective-taking message is significantly different from that of the information message (center coefficient in Fig. 1). In other words, there is something particular about the perspective-taking exercise that moved respondents to write letters to the President, in support of admitting Syrian refugees.

Yet we also find that the effect of perspective taking is short-lived. In SI Appendix, Fig. S3 breaks down the average treatment effect of perspective taking by wave, showing that wave 1 largely drives the main effect. Those who received the perspective-taking treatment were no more likely to write a letter 1 wk later than were those in the control group. At least in the context of our survey experiment, perspective taking works in the short run.

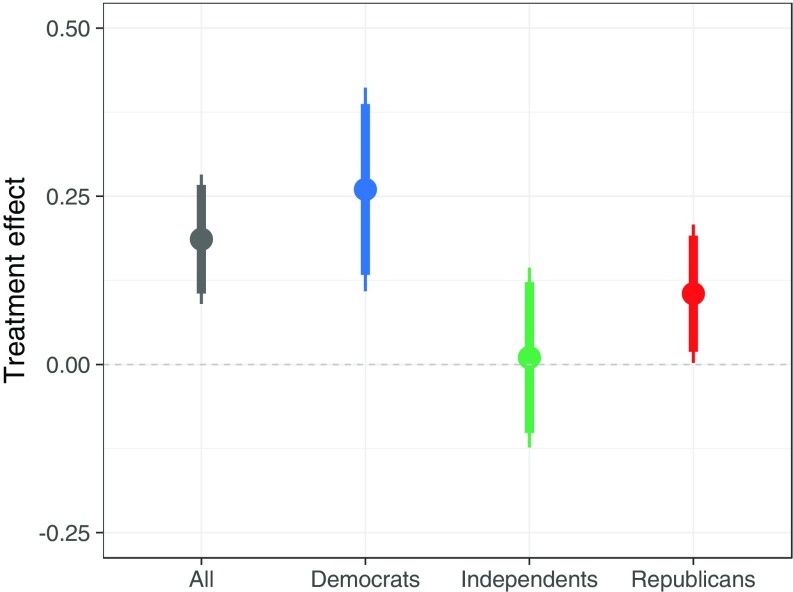

Is the effect of perspective taking restricted to certain types of respondents? Although we did not preregister the following set of analyses, it is worth investigating whether the perspective-taking exercise worked only on self-identified Democrats, who may be more predisposed to respond positively to efforts to increase refugee inclusion [a claim we confirm by looking at the probabilities of writing a supportive letter for Democrats (23%) vs. Republicans (4.6%) in the control condition—a statistically significant difference ()]. Fig. 2 illustrates the heterogenous treatment effects of our perspective-taking treatment by party ID, with the effect on the self-identified Democratic subsample in blue, the effect on the self-identified Independent subsample in green, and the effect on the self-identified Republican subsample in red.

Fig. 2.

Average treatment effect of perspective taking on the full sample (gray), the subsample of Democrats (blue), the subsample of Independents (green), and the subsample of Republicans (red). Bars show 90% and 95% confidence intervals. Wave 1 sample is shown. All graphs show treatment effects based on an OLS regression estimating Eq. 1 on various subsamples.

We find that the robust significant positive effect of perspective taking on letter writing is driven largely by Democrats, who have a 23% likelihood of writing a supportive letter in the control condition and a 34% likelihood of writing such a letter in the perspective-taking condition—a nearly 50% increase. The perspective-taking treatment moved Republicans in the positive direction as well: from 4.6% in the control condition to 7.4% in the perspective-taking treatment, a statistically significant effect as estimated in Eq. 1. Our results suggest that the perspective-taking treatment moves to action individuals from a cross-section of partisan backgrounds.

Discussion

Our findings reveal how common strategies and narratives influence public responses to refugees and how these effects vary by party. Overall, the perspective-taking treatment proved effective in promoting inclusionary behavior, but this effect is short-lived. Meanwhile, the alternative information treatment failed to move our respondents toward more inclusionary behavior, suggesting that there is something particularly effective about a perspective-taking exercise.

Our results have important implications for understanding what kinds of messages shape public opinion and public action. Importantly, it is worth considering why we find an effect of the perspective-taking treatment on behavior (letter writing), but not on attitudes (refugee ratings; SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Literature in psychology has long noted the weak relationship between attitudes and behavior (30, 31), and political scientists have recently come to similar conclusions (32, 33).

We propose that our intervention did not change attitudes but rather strengthened the attitude–behavior link. In other words, our perspective-taking exercise may have given respondents an opportunity to act on their attitudinal dispositions. Under this interpretation, our treatment provided a nudge, encouraging those who already held positive attitudes toward refugees to take action on that preference. Our perspective-taking treatment may have primed respondents’ intrinsic motivation to help others in need, which then caused them to take action when given the relatively low-cost opportunity to do so; or it may have applied extrinsic (social) pressure to act (34–36).

Although we cannot tell whether our treatment appealed to intrinsic motivation or extrinsic pressure, we find two results that give us confidence in the interpretation that perspective taking closed the attitude–behavior gap among those who already held inclusionary attitudes. First, as we have shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3, our treatment was effective only in wave 1. That our treatment worked only in the short run is consistent with the interpretation that our intervention nudged respondents to act on their positive attitudes.

Second, we find that the probability of letter writing is higher for individuals who provide higher values on our refugee rating scale (Y2) than for individuals who provide lower values. We illustrate this first with descriptive statistics presented in SI Appendix, Fig. S13, which shows the probability of letter writing for each value of Y2 in our control condition (solid line) and in our perspective-taking condition (dashed line). SI Appendix, Fig. S13 highlights where our intervention took effect: individuals who rated refugees a 7 (the highest possible rating) were more likely to write a letter under the perspective-taking condition than under the control condition (a result that is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level). This is not the case for any other value of our refugee rating scale. In other words, our intervention may have moved to action those individuals with the warmest predisposition toward refugees, and this holds for both Democrats and Republicans (SI Appendix, Figs. S14 and S16).

Because both our refugee scale and letter-writing measures were asked after the treatment, we also conduct an inference-based analysis that adjusts for posttreatment bias. To do so, we focus on a specific quantity of interest, the average controlled direct effect (ACDE), which measures the causal effect of a treatment (perspective taking) when the mediator (refugee rating) is fixed at a particular level. We apply the debiasing techniques proposed in Acharya et al. (37) to estimate the ACDE when the refugee rating is fixed at high values and when the refugee rating is fixed at low values. We find that the magnitude of the treatment effect on letter writing for individuals who gave high refugee ratings (6 or 7) is 3.5 times greater than that of the treatment effect on letter writing for individuals who gave low refugee ratings (between 1 and 5). (This finding is robust to defining high refugee ratings as a 7 and low refugee ratings as anything between 1 and 6.) Together, our descriptive and inference-based analyses support the interpretation that our intervention strengthened the attitude–behavior link for individuals with the most positive priors toward refugees.‡

Finally, we turn to the subset of respondents—Independents—for whom the perspective-taking treatment affected attitudes (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) but not behavior (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Recent work on the political behavior of Independents suggests that these individuals are less likely to take action that is perceived as partisan (40). To the extent that being supportive of refugees is a partisan issue, a plausible interpretation given the elite partisan divide on immigration politics (12), writing a letter to the next US President may have seemed to Independent respondents like partisan action. If so, it is not surprising that Independents turned down the opportunity to do so. We thus interpret our findings on the ambivalent effects of our perspective-taking treatment on Independents as consistent with the latest research on self-identified Independents in American politics.

Our results raise questions about the conditions under which, and the mechanisms through which, perspective taking promotes inclusionary behavior. In our study, a perspective-taking exercise increased inclusionary behavior, but an informational message did not. There is still much to learn about what aspects of our perspective-taking message moved respondents toward inclusion, in particular because our design does not allow us to measure whether our perspective-taking treatment instilled empathy among our respondents. Additionally, the attenuation of the effect in wave 2 raises questions about the durability of a perspective-taking exercise, particularly in a highly polarized context where respondents are likely exposed to a multitude of stimuli in the real world. We suspect this was precisely the context our participants found themselves in, during the 2 wk before a polarized presidential election (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 shows that the attenuation of the treatment effect in wave 2 is driven by a statistically significant increase () in inclusionary behavior among respondents in the control condition). Future work could also disentangle the extent to which perspective taking and other interventions designed to promote inclusion are more effective when they appeal to extrinsic pressure or intrinsic motivation. We see here an opportunity to further define the scope in which perspective-taking exercises effectively reduce prejudice and promote inclusionary behavior outside the laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kirk Bansak, Rafaela Dancygier, Guy Grossman, Dominik Hangartner, Daniel Hopkins, Yotam Margalit, Jon Rogowski, and participants at the 2017 Harvard Experiments Working Group, the 2017 Princeton Quantitative Social Science workshop, the 2017 McGill University Center for the Study of Democratic Citizenship speaker series, and the 2017 annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, for valuable feedback. All errors are the authors’.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the GitHub database (available at https://github.com/adelinelo/refugee_empathy).

*For UNHCR, for example, the “My Life as a Refugee” game (mylifeasarefugee.org/game.html) and “7 videos guaranteed to change the way you see refugees” (www.unhcr.org/innovation/7-videos-guaranteed-to-change-the-way-you-see-refugees/) “will force you to imagine what the Syria Crisis would look like in New York City or London, to see what a year of conflict could do to a child, but most importantly to recognize refugees as ordinary people.” Mercy Corps ran an experiential exhibit that created a “multidimensional and highly personal view into the daily life of the millions of people forcibly displaced from their homes…” (https://www.mercycorps.org/press-room/releases/mercy-corps-opens-beyond-survival-life-refugee-experience).

†In an online appendix at https://github.com/adelinelo/refugee_empathy, we present results for the full set of analyses we preregistered in our preanalysis plan. These results confirm that the statistical significance of the effect of perspective taking on letter writing in the short run survives the Bonferroni correction for multiple-hypothesis testing. It also confirms that we find largely null effects on respondent attitudes toward refugees, with the possible exception of attitudes toward admitting refugees who pass a security screening. Here, the perspective-taking exercise seems to move respondents toward greater inclusion on this measure as well. The statistical significance of this effect, however, passes only the 90% confidence threshold. Finally, it shows that all our results hold when we estimate Eq. 1 with a logistic regression rather than OLS for binary outcome variables.

‡Alternatively, it is possible that our attitudinal measure did not capture the attitudinal dimension on which our intervention acted. For example, our perspective-taking exercise could have engendered empathy among our respondents, urging them to act. Indeed, work in psychology finds that perspective taking is predictive of collective action of majority group members on behalf of a minority outgroup (38). Our attitudinal measure does not capture empathy, but rather is a refugee rating scale asking respondents whether or not they would let in a specific profile. It is therefore possible that the refugee rating question captures a dimension not activated by our treatment. Because we did not explicitly measure the empathy mechanism linking our intervention to our measured outcomes (39), it is difficult to know whether this is the case.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1804002115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.UNHCR 2016. Mid-year trends 2016 (UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Geneva), Technical Report.

- 2.Adida CL, Laitin DD, Valfort MA. Why Muslim Integration Fails in Christian-Heritage Societies. Harvard Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansak K, Hainmueller J, Hangartner D. How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science. 2016;354:217–222. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones JM. 2015 Americans again opposed to taking in refugees. Available at www.gallup.com/poll/186866/americans-again-opposed-taking-refugees.aspx. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 5.Jones B. 2016 Americans’ views of immigrants marked by widening partisan, generational divides. Available at www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/15/americans-views-of-immigrants-marked-by-widening-partisan-generational-divides/. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 6.Enos RD. Causal effect of intergroup contact on exclusionary attitudes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:3699–3704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317670111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ. Public attitudes toward immigration. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2014;17:225–249. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ. The hidden American immigration consensus: A conjoint analysis of attitudes toward immigrants. Am J Polit Sci. 2015;59:529–548. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karasapan O. 2017 Refugees, migrants, and the politics of fear. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2017/04/12/refugees-migrants-and-the-politics-of-fear/. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 10.Dancygier R. Immigration and Conflict in Europe. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sniderman PM, Hagendoorn L, Prior M. Predisposing factors and situational triggers: Exclusionary reactions to immigrant minorities. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2004;98:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong TK. The Politics of Immigration: Partisanship, Demographic Change, and American National Identity. Oxford Univ Press; New York: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paluck EL, Green DP. Prejudice reduction: What works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broockman D, Kalla J. Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing. Science. 2016;352:220–224. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Facchini G, Margalit Y, Nakata H. 2016. Countering public opposition to immigration: The impact of information campaigns (Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn, Germany), IZA Discussion Paper No. 10420.

- 16.Paluck EL. Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict using the media: A field experiment in Rwanda. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2009;96:574–587. doi: 10.1037/a0011989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simonovits G, Ézdi G, Kardos P. Seeing the world through the other’s eye: An online intervention reducing ethnic prejudice. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2017;112:186–193. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruneau EG, Saxe R. The power of being heard: The benefits of ‘perspective-giving’ in the context of intergroup conflict. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48:855–866. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gutsell JN, Inzlicht M. Empathy constrained: Prejudice predicts reduced mental simulation of actions during observation of outgroups. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46:841–845. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih M, Wang E, Trahan Bucher A, Stotzer R. Perspective taking: Reducing prejudice towards general outgroups and specific individuals. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2009;12:565–577. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galinsky AD, Moskowitz GB. Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2000;78:708–724. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes C, Merolla J, Karthick Ramakrishnan S. Framing Immigrants: News Coverage, Public Opinion, and Policy. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sirin CV, Valentino NA, Villalobos JD. The social causes and political consequences of group empathy. Polit Psychol. 2017;38:427–448. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ, Yamamoto T. Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit Anal. 2014;22:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heath A, Richards L. 2016 Attitudes towards immigration and their antecedents: Topline results from round 7 of the European social survey. ESS Topline Results Series, Vol 7. Available at https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/findings/ESS7_toplines_issue_7_immigration.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 26.Grigorieff A, Roth C, Ubfal D. 2016. Does information change attitudes towards immigrants? Representative evidence from survey experiments (Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn, Germany), IZA Discussion Paper No. 10419. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Brader T, Valentino NA, Suhay E. What triggers public opposition to immigration? Anxiety, group cues, and immigration threat. Am J Polit Sci. 2008;52:959–978. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buntaine MT, Prather L. Preferences for domestic action over international transfers in global climate policy. J Exp Polit Sci. 2018;5:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin W. Agnostic notes on regression adjustments to experimental data: Reexamining Freedman’s critique. Ann Appl Stat. 2013;7:295–318. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wicker AW. Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. J Soc Issues. 1969;25:41–78. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenwald AG, Pettigrew TF. With malice toward none and charity for some: Ingroup favoritism enables discrimination. Am Psychol. 2014;69:669–684. doi: 10.1037/a0036056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Acharya A, Blackwell M, Sen M. Explaining preferences from behavior: A cognitive dissonance approach. J Polit. 2018;80:400–411. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scacco A, Warren SS. Can social contact reduce prejudice and discrimination? evidence form a field experiment in Nigeria. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2018;112:654–677. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerber AS, Green DP, Larimer CW. Social pressure and voter turnout: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2008;102:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Funk P. Social incentives and voter turnout: Evidence from the Swiss mail ballot system. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2010;8:1077–1103. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panagopoulos C. Affect, social pressure and prosocial motivation: Field experimental evidence of the mobilizing effects of pride, shame and publicizing voting behavior. Polit Behav. 2010;32:369–386. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Acharya A, Blackwell M, Sen M. Explaining causal findings without bias: Detecting and assessing direct effects. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2016;110:512–529. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallett RK, Huntsinger JR, Sinclair S, Swim JK. Seeing through their eyes: When majority group members take collective action on behalf of an outgroup. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2008;11:451–470. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis M. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;44:113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klar S, Krupnikov Y. Independent Politics. Cambridge Univ Press; New York: 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.