Abstract

The widespread use of molecular-level motion in key natural processes suggests that great rewards could come from bridging the gap between the present generation of synthetic molecular machines—which by and large function as switches—and the machines of the macroscopic world, which utilize the synchronized behavior of integrated components to perform more sophisticated tasks than is possible with any individual switch. Should we try to make molecular machines of greater complexity by trying to mimic machines from the macroscopic world or instead apply unfamiliar (and no doubt have to discover or invent currently unknown) mechanisms utilized by biological machines? Here we try to answer that question by exploring some of the advances made to date using bio-inspired machine mechanisms.

Keywords: molecular machines, molecular motors, molecular robotics, catenanes, rotaxanes

Introduction—Technomimetics vs. Biomimetics

There are two, fundamentally different, philosophies for designing molecular machinery (1). One is to scale down classical mechanical elements from the macroscopic world, an approach advocated in many of the Drexlerian designs for nanomachines (2) and also the inspiration behind “nanocars” (3–7), “molecular pistons” (8), “molecular elevators” (9), “molecular wheelbarrows” (10), and other technomimetic (11) molecules designed to imitate macroscopic objects at the molecular level (1). An advantage of this approach is that the engineering concepts behind such machines and mechanisms are well understood in terms of their macroscopic counterparts; a drawback is that many of the mechanical principles upon which complex macroscopic machines are based are inappropriate for the molecular world (1, 12).

An alternative philosophy is to try to unravel the workings of an already established nanotechnology, biology, and apply those concepts to the design of synthetic molecular machines. A potential upside of this, biomimetic, approach is that such designs are clearly well-suited to functional machines that operate at the nanoscale, even when limited, as nature is, to the use of only 20 different building blocks (amino acids), ambient temperatures and pressures, and water as the operating medium. However, a major issue in pursuing this second strategy is that the only “textbook” we have to follow is unclear: Biological machines are so complex that it is often difficult to deconvolute the reasons behind the dynamics of individual machine parts. How and why does each peptide residue move in the way it does in order for kinesin to walk along a microtubule; which conformational, hydrogen bonding, and solvation changes are necessary to bring about transport; and which only occur as a consequence of other intrinsically required intramolecular rearrangements? Applying fundamental principles deduced from small-scale physics and biomachines is the approach our group has adopted in building molecular machines over the past two decades (13). Here we outline progress on this path to synthetic nanomachines, the application of bio-inspired mechanisms to the design of molecular machines.

Simple Machines

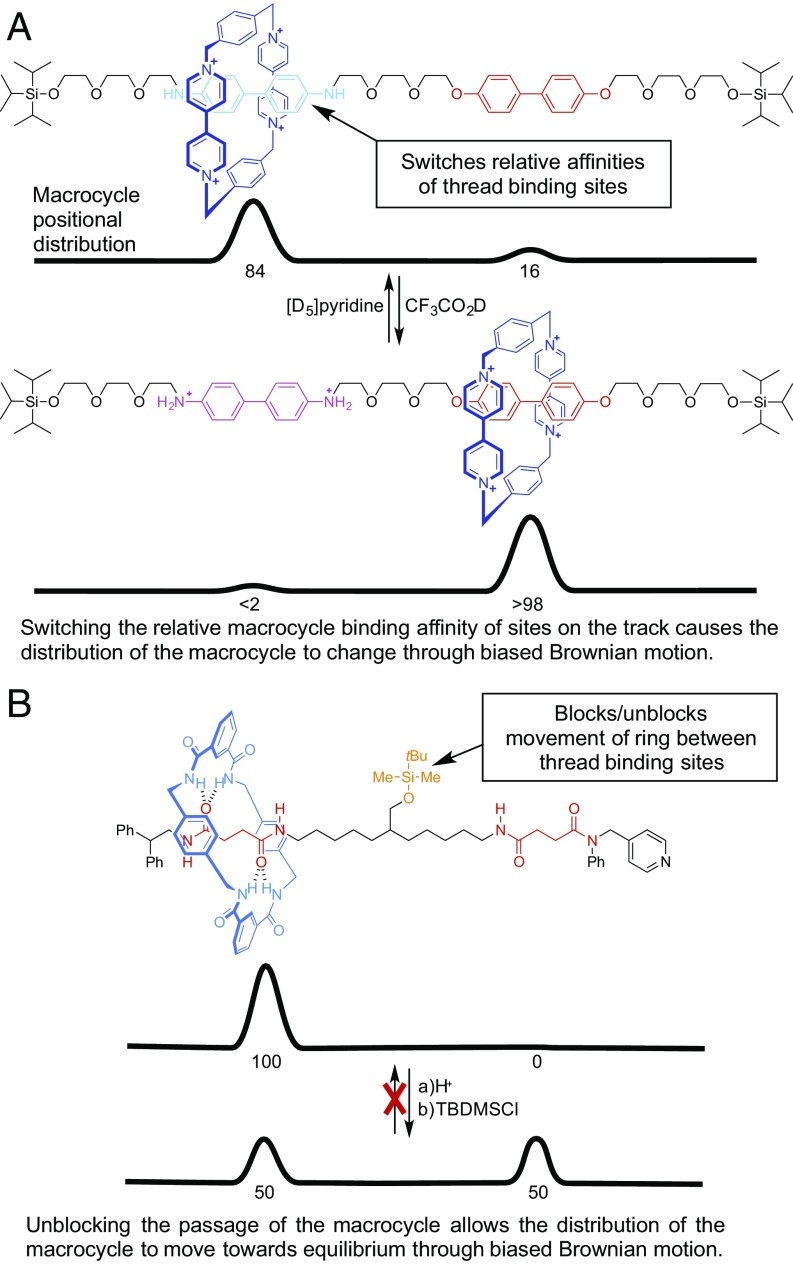

Since Stoddart’s invention of the switchable molecular shuttle (Fig. 1A) (14), chemists have used molecular switching to perform a variety of “on”/“off” tasks with synthetic mechanically interlocked molecules (15–17). Catenane and rotaxane switches have been shown to act as bits in molecular electronics (18, 19) and used for chiroptical switching (20), for fluorescence switching (21), for the writing of information in polymer films (22), in controlled release delivery systems (23), for switchable catalysts (24), and as “molecular muscles” (25, 26). However, to make molecular machines that can perform more complex tasks, it is necessary to integrate the dynamics of individual molecular machine components in a way that achieves more than just the sum of the respective parts.

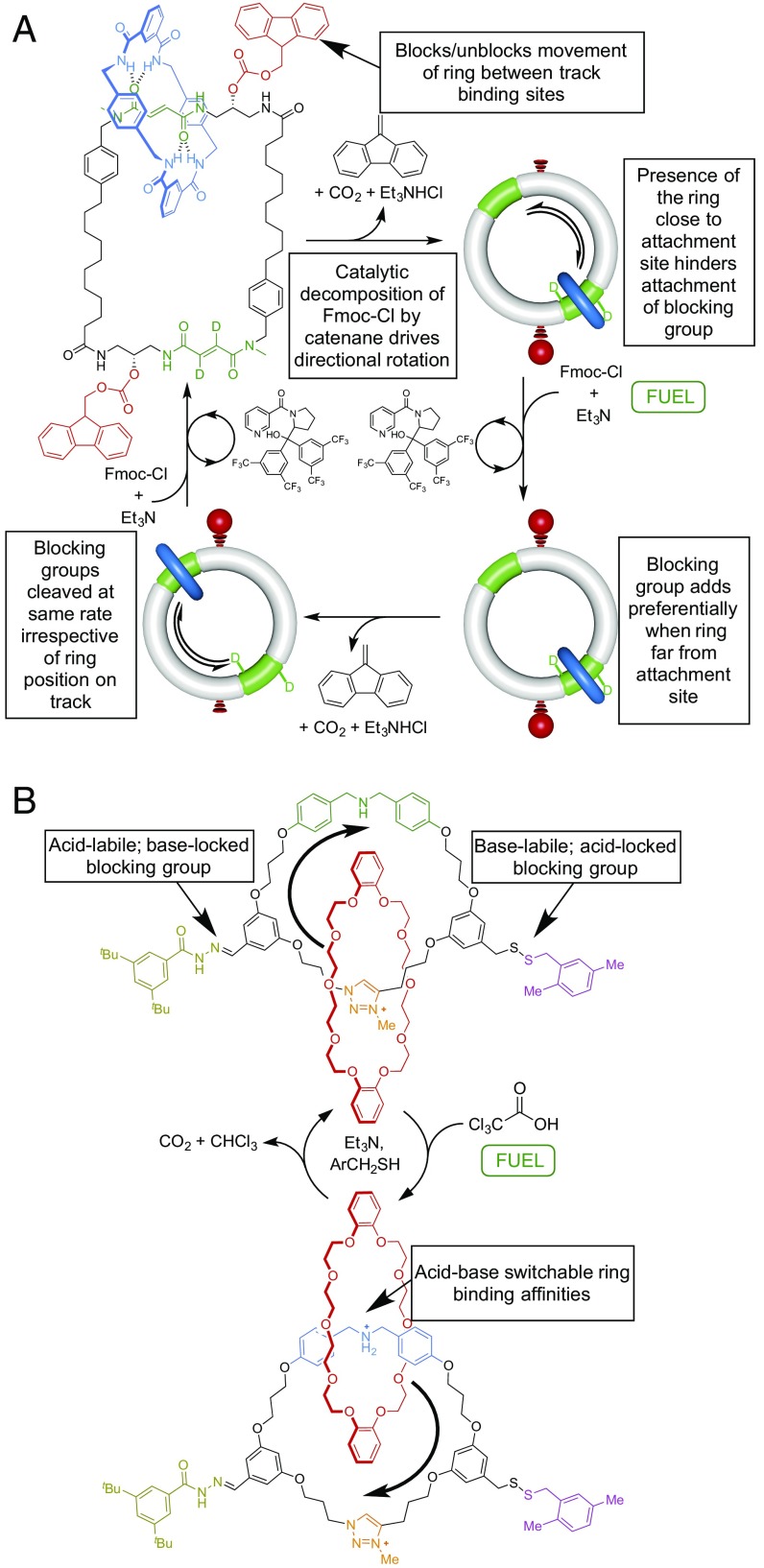

Fig. 1.

Simple molecular machine mechanisms. (A) Switching of the thermodynamically favored ring position in a molecular shuttle (25), a process used in numerous (1, 13–26) functional rotaxane switches. (B) Blocking/unblocking of the ring movement between the compartments of a rotaxane (30). Both actions result in biased Brownian motion of the ring along the track. However, note that the consequence of the switching operation in A (i.e., the change in the distribution of the macrocycle) is undone by reversing the switch state, whereas the result of the unblocking action in B is not undone by simply reattaching the blocking group.

Compound Machines—From Switches to Ratchets

Before the introduction of kinematic theory (27), scientists and engineers considered there to be six different types of simple mechanical machines (28). These are the three Archimedian simple machines (29)—the lever, pulley, and screw—plus the wheel-and-axle (including gears), inclined plane, and wedge. Connecting “simple machines” in such a way that the output of one provides the input for another can integrate their mechanisms and produce “compound machines” capable of performing more complex tasks. For example, a pair of scissors can be considered a compound machine consisting of levers (the handles and blades pivoting about a fulcrum) connected to wedges (the cutting edges of the blades). Because matter behaves so differently at different length scales, several types of simple machines cannot perform the same function they execute at macroscopic scales in the low Reynolds number and Brownian motion-dominated environment in which molecular-sized machines operate. An inclined plane, for example, has no mechanical advantage nor effect on the motion of a molecular object; it is the height of an energy barrier, not its shape, that determines the ease (i.e., rate) at which a barrier to molecular motion is overcome (1).

In a regime where inertia and momentum are irrelevant in mechanical terms, the basic mechanisms of molecular machines include switching of relative binding affinities at different sites and modifying the kinetics for changes of position of components that occur by random thermal motion (Fig. 1) as well as binding-release mechanisms, catalytic action, etc. To produce compound molecular machines capable of more advanced task performance than simple molecular machines, one can follow a similar strategy to that of making compound machines in the macroscopic world—namely, connect the actions of simple molecular machines in ways that the output of one machine action provides an input for the next.

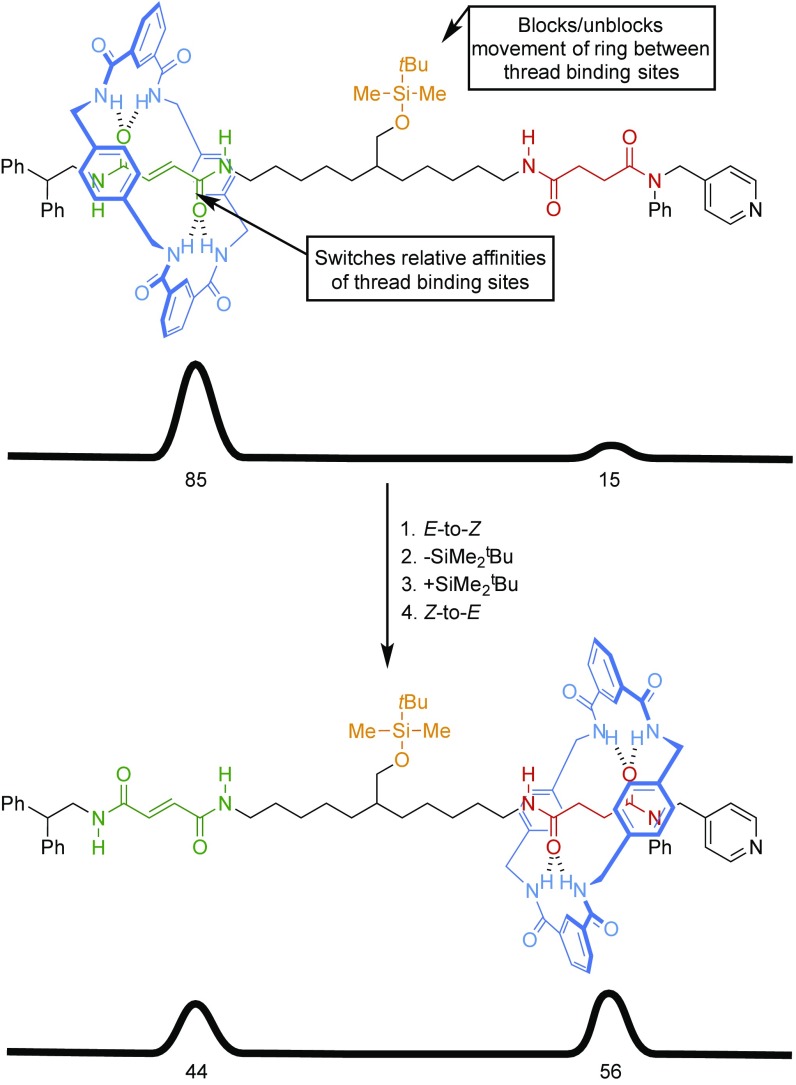

The first such compound molecular machines were introduced over the period 2003–2007 (30–33). An example is the rotaxane shown in Fig. 2 (30). This combines the switching of the thermodynamically favored position of the ring (brought about by E-Z isomerization of the olefin binding site) with steric blocking of ring movement (caused by the presence of the silyl ether). By synchronizing these two simple machine processes [(1) E-to-Z isomerization, (2) removal of the silyl ether, (3) reattachment of the silyl ether, (4) Z-to-E isomerization], it is possible to achieve something that neither of the individual machine processes can accomplish in isolation—namely, drive the macrocycle distribution away from its equilibrium value of 85:15 (fumaramide:succinamide occupation) to 44:56 (fumaramide:succinamide occupation). The profundity and generality of this outcome should not be underestimated: Simply removing the terminal stopper groups creates a molecular pump; connecting the ends so that the output of the machine mechanism becomes the next input creates a rotary motor. The same motor mechanism is responsible for each type of machine.

Fig. 2.

A compound molecular machine (30). Note that the thread is structurally identical in both states of the machine shown; only the distribution of the macrocycle differs. Combining (and synchronizing the operation of) a switch for the thermodynamically favored position of the macrocycle on the axle with the attachment/release of a blocking group enables the macrocycle distribution to be driven away from its equilibrium value, a task that cannot be accomplished by a simple machine process.

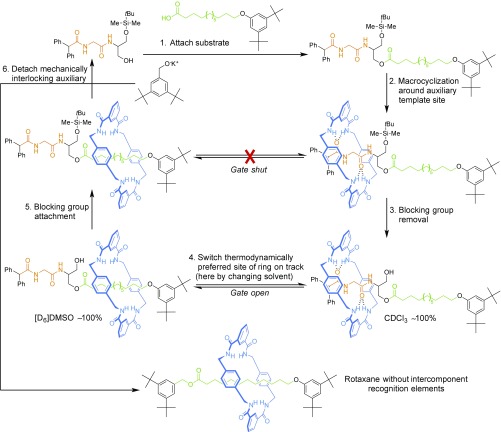

A similar combination of switching of the relative affinity of the ring for different sites on an axle, with subsequent addition of a blocking group to lock in the change of position of the ring, was used to synthesize rotaxanes without permanent recognition elements between macrocycle and thread (Fig. 3) (34). Hydrogen bond-directed assembly of a benzylic amide macrocycle around a peptide “mechanical interlocking auxiliary” efficiently generates a [2]rotaxane (Fig. 3, step 2). Removal of a bulky silyl ether allows the ring to access the full length of the thread (Fig. 3, step 3). In chloroform, the macrocycle hydrogen bonds to the peptide, but in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) the solvent competes for the amide hydrogen bonding sites (of both macrocycle and thread), and the alkyl chain minimizes its area exposed to polar solvent by burying itself within the macrocycle cavity (Fig. 3, step 4). The change of position of the ring on the thread is locked by resilylation (Fig. 3, step 5) and the auxiliary removed by transesterification (Fig. 3, step 6) to leave a [2]rotaxane with no residual recognition elements between macrocycle and thread.

Fig. 3.

Synthesis of a [2]rotaxane without intercomponent recognition elements by ratcheted transport of a macrocycle along a track (34). A remarkable feature of the machine is that it enables the synthesis of rotaxanes without complementary binding sites on the two components of the threaded product. Efficient synthetic strategies to mechanically interlocked compounds without recognition elements were otherwise unavailable before the invention of active template synthesis (35, 36).

By adding escapement mechanisms to the system shown in Fig. 2 and other related compound machines, the components of [2]catenanes (31) and [3]catenanes (32) could be directionally rotated, the first examples of Brownian ratchet mechanisms being introduced into the designs of synthetic molecular machines (31–33). The idea of using unbiased thermal fluctuations to drive directed motion has its origins in the visionary works of von Smoluchowski (37) and Feynman (38), and a theoretical description of energy and information ratchets had been described (39, 40) for (bio)molecular systems by Astumian in the 1990s. In the early 2000s, our group recognized that molecular rings mechanically locked onto linear or cyclic axles [the catenane and rotaxane architectures pioneered by Sauvage (16) and Stoddart (17) in the 1980s and 1990s] could be considered as Brownian particles (the rings) on a potential energy surface (the axle) and their dynamics thus controlled by incorporating Brownian ratchet mechanisms into synthetic molecular machine designs: “The way in which the principles of an energy ratchet can be applied to a catenane architecture is not to consider the whole structure as a molecular machine, but rather to view one macrocycle as a motor that transports a substrate—the other ring—directionally around itself” (31) [see also Astumian’s “chemical peristalsis” analysis (41) of our original [3]catenane motor (32) and a [2]catenane analog (1)]. This realization led to the first energy ratchets (directional transport caused by varying potential energy minima and maxima independent of the position of the particle on the potential energy surface) (31, 32), the first information ratchets (directional transport caused by kinetics dependent on the position of the particle) (33, 42, 43), the first linear molecular motors (30, 33), and a second type, after the Feringa overcrowded alkenes (7), of rotary molecular motors.

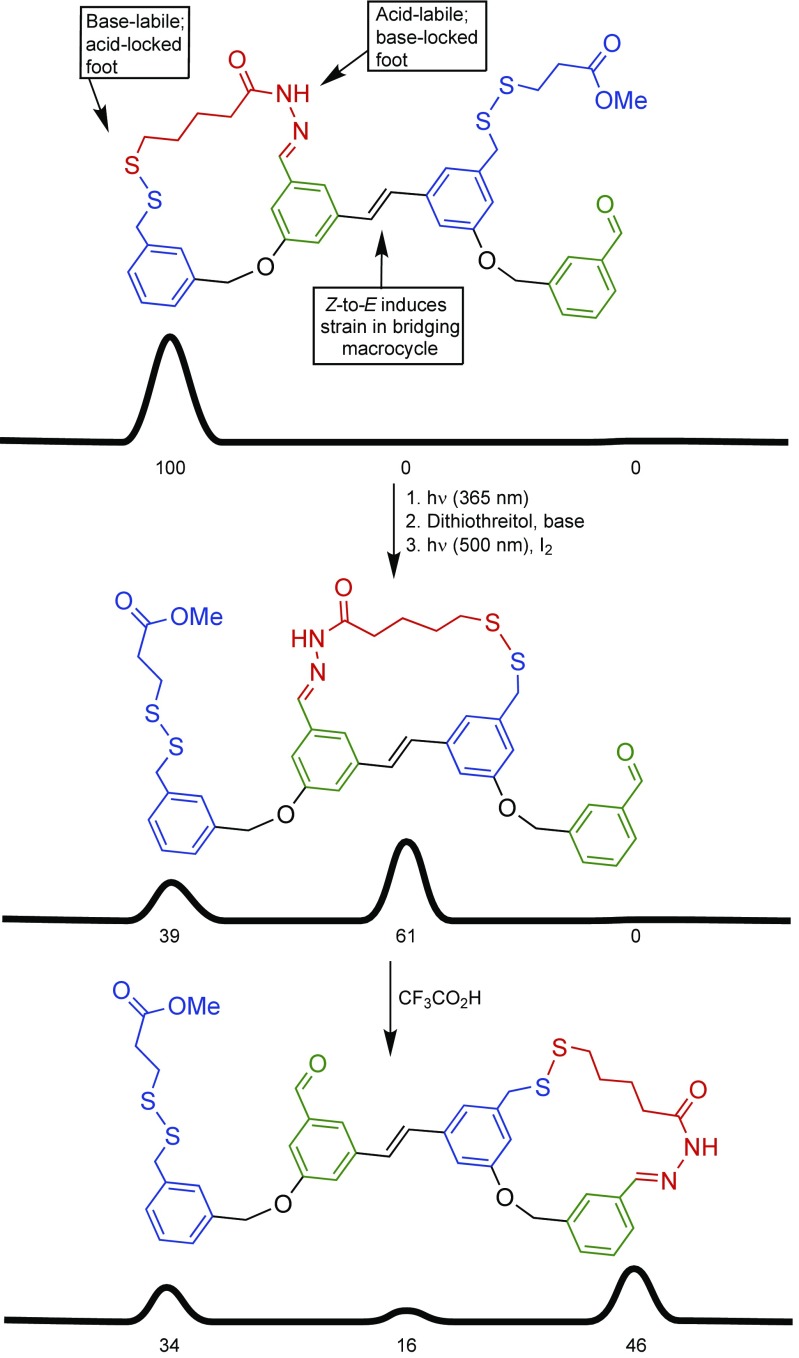

Such ratchet mechanisms are the general solutions for molecular motors, both rotary and linear, and have been improved and expanded upon by us and others over the last decade (44–50), including DNA motors (44), ratcheted small-molecule walkers (45, 46) (Fig. 4), and pumps (47, 48). The most recent examples of chemically fueled catenane and rotaxane motors feature autonomous operation (49) (Fig. 5A) and directionality of the component movements synchronized to the addition of a chemical fuel (50) (Fig. 5B). These latter developments are particularly significant, as they demonstrate how several simple machine processes can be integrated and made to work together using a single energy input. Biological motors are driven by catalysis of a chemical reaction based on information ratchet mechanisms (51). The molecular motor shown in Fig. 5A works in identical fashion: The components are directionally driven by catalysis of the decomposition of Fmoc-Cl by the catenane. It is the first example of the implementation of an information ratchet to continuously drive cyclic motion in a synthetic molecular machine. The molecular motor shown in Fig. 5B illustrates that pulses of a chemical fuel can also be used to drive energy ratchet motors.

Fig. 4.

A molecule that “walks” directionally along a molecular track using a light-fueled energy ratchet mechanism (46). The E/Z state of the stilbene molecular switch modulates the strain in the walker as it bridges the central footholds; synchronizing the stilbene switching with labilizing the orthogonal foot-track interactions generates directional transport of the walker along the track.

Fig. 5.

Compound molecular machines with multiple simple machine mechanisms that operate in a synchronized fashion through a common input. (A) A chemically fueled molecular motor that runs autonomously in the presence of Fmoc-Cl (49). The rate of addition of an Fmoc blocking group to a free OH group on the track is faster when the site of attachment is not hindered by the presence of the macrocycle, meaning that blocking groups attach to the track faster with respect to one face of the macrocycle than the other, biasing the Brownian motion of the ring in one direction (an information ratchet mechanism). (B) A molecular motor driven by pulses of Cl3CCO2H (50). The base-catalyzed decarboxylation of Cl3CCO2H changes the environment from acidic to basic; the thermodynamically favored position of the ring and the lability of the blocking groups switches with the change in acidity (an energy ratchet mechanism).

Other Types of Compound Molecular Machine

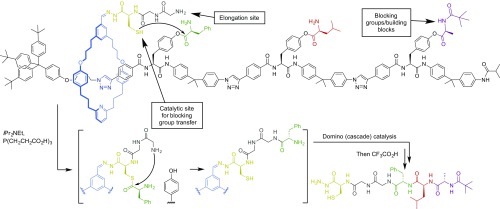

Compound molecular machines are not limited to ratchet mechanisms; the integration of other simple molecular machine processes can produce other advanced functions. The combination of blocking groups that are removed in a particular order because of a rotaxane’s structure, together with a pendant strand that possesses both a regenerable catalytic site and an elongation site, has been used to make rotaxanes in which the macrocycle moves directionally along the track, removing and adding together building blocks in a predetermined order to form a sequence-defined oligomer (Fig. 6) (52–54). In the rotaxane shown in Fig. 6, the macrocycle carries a thiolate group that iteratively removes amino acids in sequence from the strand and transfers them to a peptide-elongation site through native chemical ligation as the macrocycle moves along the track. It is reminiscent of (although much simpler than) the task performed by the ribosome and of some aspects of the way that biology makes sequence polymers in general—that is, by using molecular machines that move along tracks to direct the sequence that monomers are assembled.

Fig. 6.

A compound molecular machine that assembles a tripeptide of specific sequence by traveling along a track loaded with α-amino acid building blocks (52).

Molecular Robotics

The mechanical manipulation of matter at atomic-length scales has fascinated scientists since it was proposed by Feynman in his celebrated lecture “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom” (55). Indeed, the concept of using molecules to manipulate other molecules in robotic fashion is an intriguing one that has some precedence in biology: For example, in metazoan fatty acid synthase, a growing fatty acid chain, tethered to an embedded carrier protein, is passed between enzyme domains in the protein superstructure in a manner reminiscent of the way a robotic arm manipulates objects on a factory assembly line (56). By integrating the actions of several simple molecular machine functions—two distinct gripping/release actions (substrate-to-machine and substrate-to-platform) and positional switching of a “robotic arm”—a compound molecular machine has been produced that is able to selectively transport a molecular cargo in either direction between two spatially distinct, chemically similar, sites on a molecular platform without the substrate ever exchanging with others in the bulk (Fig. 7) (57).

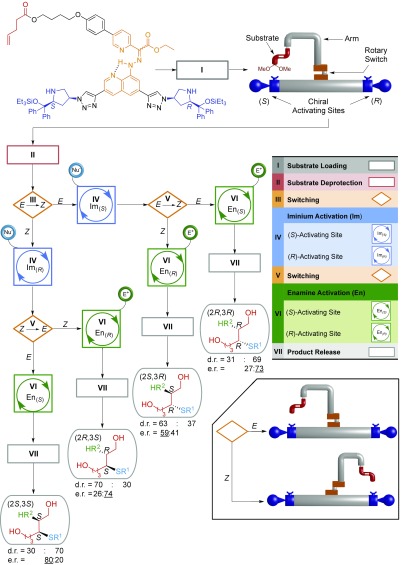

Fig. 7.

Multistage operation of a bidirectional small-molecule transporter that uses a rotary switch to control a molecular robotic arm (57).

With this machine, transport of the substrate is controlled by inducing sequential conformational and configurational changes within an embedded hydrazone rotary switch (58) that steers the robotic arm. When the substrate is being moved through a change in position of the arm, the substrate–arm linkage is kinetically locked and the substrate–platform bond labile. When the substrate is released by the arm, the substrate–platform bond is kinetically locked in place. By controlling the order that each simple machine function occurs, it is possible to program the molecular machine to selectively transport the substrate either from left-to-right or from right-to-left in a one-pot reaction sequence. In chemical terms, this is the selective synthesis of constitutional isomers through intramolecular rearrangements that can be induced to proceed in either direction, something that is difficult or impossible to achieve in any other way.

Just as biological molecular machines position substrates to direct chemical reaction sequences, it is possible to adapt this type of machine to produce different outputs from a series of molecular robot-mediated chemical reactions. The compound molecular machine moves a substrate between different activating sites to achieve different product outcomes from chemical synthesis (Fig. 8) (59). The molecular robot can be programmed to stereoselectively produce, in a sequential one-pot reaction, an excess of any of the four possible diastereoisomers from the addition of a thiol and an alkene to an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde in a tandem reaction process. The stereodivergent synthesis includes access to diastereoisomers that cannot be selectively synthesized through conventional iminium-enamine organocatalysis.

Fig. 8.

Programable synthesis of any one of four stereoisomers by a small-molecule robot (59). Using a thiol nucleophile for the first reaction (iminium activation of the substrate by the machine) and an electron-poor alkene electrophile for the second reaction (enamine activation of the substrate by the machine), any of the four possible products can be selectively made by the robot in one pot through different programing.

Outlook

Molecules that resemble in their appearance machines familiar to us from our everyday world have seductive appeal, but numerous mechanical mechanisms that work at the macroscopic scale are physically impossible at the molecular level (including pendulums, spring-loaded trapdoors, pistons, crankshafts, the internal combustion engine, inclined planes, wedges, etc.). Other machine parts scale down in some respects but not others. For example, the rotation of the aromatic ring blades of interdigitated triptycene residues can be coupled in the same way as meshed mechanical cogwheels; the rotors look and behave in that respect like gears (60). However, mechanical gears are designed to move with uniform angular velocity within macroscopic compound machines and this can never be the case for rotors within molecular machines. Such issues make extrapolation of mechanical machine concepts to the molecular level fraught with difficulty. Indeed, many of the current generation of technomimetic molecular machines are iconic models of machines; that is, they look like but do not function as the original object does, in the same way that a model aeroplane does not fly like a jumbo jet (61). Few, if any, technomimetic molecular machines are analogic models, resembling the parent machine in behavior as well as form.

The alternative is to design nanomachines that work in broadly the same way as biology. As with classical engineering, a route to machine complexity is to integrate the actions of several simple machine processes to generate advanced functions that cannot be achieved by the action of any of the machine parts individually. Given that most complex machine mechanisms cannot be scaled to the environments in which molecular machines operate, it may prove difficult for technomimetic designs to produce nanomachines that are significantly more advanced in terms of mechanism than the rudimentary systems made to date. However, all of biology is based on molecular machines that use (and appear to require) nontrivial mechanisms to carry out the sophisticated and useful tasks they perform. Through adopting the basic principles of how such machines work, bio-inspired mechanisms can enable the construction of molecular machines that are more than just switches, with compound mechanisms based on the integration of several simpler working parts.

Acknowledgments

We thank East China Normal University, the European Research Council (ERC; Advanced Grant 339019), and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC; Grant EP/P027067/1) for funding. D.A.L. is a Royal Society Research Professor.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Kay ER, Leigh DA, Zerbetto F. Synthetic molecular motors and mechanical machines. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:72–191. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drexler KE. Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology. Anchor Books; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirai Y, Osgood AJ, Zhao Y, Kelly KF, Tour JM. Directional control in thermally driven single-molecule nanocars. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2330–2334. doi: 10.1021/nl051915k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudernac T, et al. Electrically driven directional motion of a four-wheeled molecule on a metal surface. Nature. 2011;479:208–211. doi: 10.1038/nature10587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saywell A, et al. Light-induced translation of motorized molecules on a surface. ACS Nano. 2016;10:10945–10952. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b05650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson GJ, García-López V, Petermeier P, Grill L, Tour JM. How to build and race a fast nanocar. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12:604–606. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2017.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feringa BL. The art of building small: From molecular switches to motors (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:11060–11078. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashton PR, et al. A light-fueled ‘piston cylinder’ molecular-level machine. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11190–11191. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badjić JD, Balzani V, Credi A, Silvi S, Stoddart JF. A molecular elevator. Science. 2004;303:1845–1849. doi: 10.1126/science.1094791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez-Bueno G, Rapenne G. Technomimetic molecules: Synthesis of a molecular wheelbarrow. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:6261–6263. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gakh AA. Molecular Devices: An Introduction to Technomimetics and Its Biological Applications. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astumian RD. Design principles for Brownian molecular machines: How to swim in molasses and walk in a hurricane. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:5067–5083. doi: 10.1039/b708995c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay ER, Leigh DA. Rise of the molecular machines. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:10080–10088. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bissell RA, Córdova E, Kaifer AE, Stoddart JF. A chemically and electrochemically switchable molecular shuttle. Nature. 1994;369:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erbas-Cakmak S, Leigh DA, McTernan CT, Nussbaumer AL. Artificial molecular machines. Chem Rev. 2015;115:10081–10206. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauvage J-P. From chemical topology to molecular machines (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:11080–11093. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoddart JF. Mechanically interlocked molecules (MIMs)—Molecular shuttles, switches, and machines (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:11094–11125. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collier CP, et al. Electronically configurable molecular-based logic gates. Science. 1999;285:391–394. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green JE, et al. A 160-kilobit molecular electronic memory patterned at 10(11) bits per square centimetre. Nature. 2007;445:414–417. doi: 10.1038/nature05462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bottari G, Leigh DA, Pérez EM. Chiroptical switching in a bistable molecular shuttle. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13360–13361. doi: 10.1021/ja036665t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez EM, Dryden DTF, Leigh DA, Teobaldi G, Zerbetto F. A generic basis for some simple light-operated mechanical molecular machines. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12210–12211. doi: 10.1021/ja0484193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leigh DA, et al. Patterning through controlled submolecular motion: Rotaxane-based switches and logic gates that function in solution and polymer films. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:3062–3067. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen TD, et al. A reversible molecular valve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10029–10034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504109102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco V, Leigh DA, Marcos V. Artificial switchable catalysts. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:5341–5370. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00096c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiménez MC, Dietrich-Buchecker C, Sauvage J-P. Towards synthetic molecular muscles: Contraction and stretching of a linear rotaxane dimer. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:3284–3287. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3284::aid-anie3284>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coutrot F, Romuald C, Busseron E. A new pH-switchable dimannosyl[c2]daisy chain molecular machine. Org Lett. 2008;10:3741–3744. doi: 10.1021/ol801390h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beggs JS. Kinematics. Hemisphere Publishing Corp.; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleghorn WL, Dechev N. Mechanics of Machines. 2nd Ed Oxford Univ Press; Oxford: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendick J. Archimedes and the Door of Science. Bethlehem Books; Warsaw, ND: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterjee MN, Kay ER, Leigh DA. Beyond switches: Ratcheting a particle energetically uphill with a compartmentalized molecular machine. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4058–4073. doi: 10.1021/ja057664z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernández JV, Kay ER, Leigh DA. A reversible synthetic rotary molecular motor. Science. 2004;306:1532–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1103949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leigh DA, Wong JKY, Dehez F, Zerbetto F. Unidirectional rotation in a mechanically interlocked molecular rotor. Nature. 2003;424:174–179. doi: 10.1038/nature01758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serreli V, Lee C-F, Kay ER, Leigh DA. A molecular information ratchet. Nature. 2007;445:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature05452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hannam JS, et al. Controlled submolecular translational motion in synthesis: A mechanically interlocking auxiliary. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3260–3264. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aucagne V, Hänni KD, Leigh DA, Lusby PJ, Walker DB. Catalytic “click” rotaxanes: A substoichiometric metal-template pathway to mechanically interlocked architectures. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2186–2187. doi: 10.1021/ja056903f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denis M, Goldup SM. The active template approach to interlocked molecules. Nat Rev Chem. 2017;1:0061. [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Smoluchowski M. Experimentell nachweisbare, der üblichen Thermodynamik widersprechende Molekularphänomene. Phys Z. 1912;13:1069–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feynman RP. 1963. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, (Addison-Wesley, Boston), Vol 1, Chap 46.

- 39.Astumian RD, Bier M. Fluctuation driven ratchets: Molecular motors. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;72:1766–1769. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Astumian RD, Derényi I. Fluctuation driven transport and models of molecular motors and pumps. Eur Biophys J. 1998;27:474–489. doi: 10.1007/s002490050158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Astumian RD. Chemical peristalsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1843–1847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409341102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarez-Pérez M, Goldup SM, Leigh DA, Slawin AMZ. A chemically-driven molecular information ratchet. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1836–1838. doi: 10.1021/ja7102394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carlone A, Goldup SM, Lebrasseur N, Leigh DA, Wilson A. A three-compartment chemically-driven molecular information ratchet. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8321–8323. doi: 10.1021/ja302711z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green SJ, Bath J, Turberfield AJ. Coordinated chemomechanical cycles: A mechanism for autonomous molecular motion. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;101:238101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.238101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Delius M, Geertsema EM, Leigh DA. A synthetic small molecule that can walk down a track. Nat Chem. 2010;2:96–101. doi: 10.1038/nchem.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrell MJ, Campaña AG, von Delius M, Geertsema EM, Leigh DA. Light-driven transport of a molecular walker in either direction along a molecular track. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:285–290. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ragazzon G, Baroncini M, Silvi S, Venturi M, Credi A. Light-powered autonomous and directional molecular motion of a dissipative self-assembling system. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10:70–75. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng C, et al. An artificial molecular pump. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10:547–553. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson MR, et al. An autonomous chemically fuelled small-molecule motor. Nature. 2016;534:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature18013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Erbas-Cakmak S, et al. Rotary and linear molecular motors driven by pulses of a chemical fuel. Science. 2017;358:340–343. doi: 10.1126/science.aao1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Astumian RD. How molecular motors work—Insights from the molecular machinist’s toolbox: The Nobel prize in chemistry 2016. Chem Sci. 2017;8:840–845. doi: 10.1039/c6sc04806d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewandowski B, et al. Sequence-specific peptide synthesis by an artificial small-molecule machine. Science. 2013;339:189–193. doi: 10.1126/science.1229753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Bo G, et al. Efficient assembly of threaded molecular machines for sequence-specific synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5811–5814. doi: 10.1021/ja5022415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Bo G, et al. Sequence-specific β-peptide synthesis by a rotaxane-based molecular machine. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:10875–10879. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feynman RP. There’s plenty of room at the bottom. Eng Sci. 1960;23:22–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan DI, Vogel HJ. Current understanding of fatty acid biosynthesis and the acyl carrier protein. Biochem J. 2010;430:1–19. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kassem S, Lee ATL, Leigh DA, Markevicius A, Solà J. Pick-up, transport and release of a molecular cargo using a small-molecule robotic arm. Nat Chem. 2016;8:138–143. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Su X, Aprahamian I. Switching around two axles: Controlling the configuration and conformation of a hydrazone-based switch. Org Lett. 2011;13:30–33. doi: 10.1021/ol102422h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kassem S, et al. Stereodivergent synthesis with a programmable molecular machine. Nature. 2017;549:374–378. doi: 10.1038/nature23677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iwamura H, Mislow K. Stereochemical consequences of dynamic gearing. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mislow K. Molecular machinery in organic chemistry. Chemtracts: Org Chem. 1989;2:151–174. [Google Scholar]