Abstract

Objective: This study was set up to evaluate the efficacy of a concentrated surfactant-based wound dressing (with and without silver sulfadiazine [SSD]) on wound repair, by investigating their ability to enhance human dermal fibroblast proliferation and viability. In addition, the wound dressings were evaluated for their ability to suppress biofilms in a three-dimensional (3D) in vitro wound biofilm model and modulate the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα).

Approach: Problematic biofilms are well known to affect fibroblast and keratinocyte viability. To assess wound repair and inflammatory cytokine modulation, a direct cytotoxicity assay and a 3D keratinocyte-fibroblast model were employed.

Results: At 1 and 7 days posttreatment, the non-antimicrobial dressing was noncytotoxic and the antimicrobial dressing was moderately cytotoxic to adult human dermal fibroblasts cells. Within the 3D wound model, the biofilm demonstrated a decelerating effect on wound closure and a decrease in viable cells. When the non-antimicrobial- and antimicrobial-based concentrated surfactant-based wound dressing was applied to the wound model, reduced biofilm was observed. The application of wound dressings to the biofilm-infected wound also resulted in a reduction of IL-6 and TNFα. The concentrated surfactant-based wound dressing without an antimicrobial was shown to enhance cellular viability and migration.

Innovation and Conclusion: We have demonstrated the ability of a surfactant-based wound dressing to minimize the deleterious effects of a wound biofilm, modulate the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, and enhance cellular proliferation in a biofilm-infected wound model. Furthermore, the non-antimicrobial-based concentrated surfactant dressings did not affect cellular viability and therefore represents a multifaceted approach to the treatment of wounds infected with biofilms.

Keywords: : biofilm, biofilm control, surfactant, wound, wound dressing, wound healing, cytotoxicity

Steven L. Percival, PhD

Introduction

When acute wounds fail to heal through a complex and well-regulated wound healing process, they can be defined as being chronic and are characterized by a prolonged inflammatory response, a defective wound matrix, and failure of reepithelialization.1 Persistent and elevated inflammatory cell activity have been shown to be a critical factor in the development of a chronic wound2,3 and can be induced by both endogenous factors, such as underlying physiological conditions, and exogenous factors, such as persistent microbial colonization and biofilms.4

Biofilms are microorganisms that are attached to a surface or each other and are encased in a hydrated polymeric matrix referred to as extracellular polymeric substance (EPS).5 Biofilm-related infections are persistent and are now considered to be prevalent in all chronic wounds.6 Given the ability of microbial biofilms to form on almost, if not all, surfaces, microorganisms within the wound will also attach to the dressings that are being used to help manage the wound.4 The formation of biofilms on the surface of dressings could potentially increase the release of bacterial virulence factors, including N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHL molecules), and toxins into the wound. This in combination with dissemination of planktonic microbes and biofilm into the wound results in a constant state of chronic inflammation within the wound. Increased levels of AHL molecules within the wound could also potentially encourage further biofilm formation on wound tissue.7 Topical treatments used on the wound, which are aimed at the prevention of biofilms, should therefore also be considered beneficial in preventing colonization of wound dressings.

Microorganisms found within chronic wounds are polymicrobial in nature8 and therefore for the treatment of infected chronic wounds to be successful, any antimicrobial therapy should be broad spectrum in activity, that is, efficacious against both gram-negative and gram-positive aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, fungi, and yeasts, while also being effective against biofilms. Consequently, it is important that wound dressings demonstrate an ability to suppress the effects that biofilms cause and provide an environment that supports enhanced cellular healing.

Clinical problem

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of concentrated surfactant-based wound dressings (with and without 1% silver sulfadiazine [SSD]) on wound repair by investigating their ability to suppress interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), proinflammatory cytokines, and enhance epithelial keratinocyte and fibroblast migration, proliferation, and viability. In addition, the wound dressings were evaluated for their ability to suppress the detrimental effects of biofilms in a novel wound biofilm model.

Materials and Methods

Wound dressings

Two, nonionic surfactant-based wound dressings were investigated in this study. First, Plurogel® and Plurogel SSD (PSSD—which contains 1% silver sulfadiazine; Medline Industries, Inc.). Plurogel is a biocompatible and water-soluble primary wound dressing, composed of a concentrated surfactant (Poloxamer 188, [Plurogel] and Triton-100).

Bacterial strains

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 were cultured using Tryptone Soya Agar (TSA; Oxoid, United Kingdom) and Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB, Oxoid).

Human dermal fibroblasts culture

Primary adult human dermal fibroblasts (HDFa) (ATCC; LGC Standards, United Kindgom) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) GlutaMAX™ (Gibco™; ThermoFisher Scientific, United Kindgom) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone™, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, United Kindgom) and 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin (Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kindgom). Cells were cultured until they were ∼90% confluent and were then seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL/well into 24-well culture plates. The cells were used at passage 6 in this study.

Direct contact cell viability assay

Cells were incubated for 24 h (5% CO2, 37°C, and humidified conditions) so that they formed a 50–60% confluent monolayer. This incubation period ensures cell recovery, adherence, and progression to exponential growth phase. Each plate was examined under a phase contrast microscope to ensure that cell growth was relatively even across the microtiter plate and to identify experimental errors. After 24 h of incubation, 100 μL of treatment (Plurogel and PSSD) or control medium, or Triton-100 was added to the appropriate wells and incubated for 24 h (5% CO2, 37°C, and humidified conditions). At days 1 and 7 post-treatment, cells were examined qualitatively using a phase contrast microscope to determine attachment and growth characteristics of the control and treated cells. At 4 days, the culture media (DMEM) were changed.

At 1 and 7 days post-treatment, cytotoxicity and cell proliferation were also quantitatively evaluated using a CyQUANT cell proliferation assay kit from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, United Kindgom) following the manufacturer's instructions. The CyQUANT assay uses a proprietary green fluorescent dye (CyQUANT GR dye) that exhibits strong fluorescence enhancement when bound to cellular nucleic acids. Fluorescence was measured using an FLX800 fluorimeter with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 530 nm. The fluorescence values of samples treated with Plurogel, PSSD, and Triton-100 were converted into a percentage of cell viability by comparing to the culture medium control. Values are based on an average of 3 experiments ± standard deviations.

Three-Dimensional keratinocyte-fibroblast coculture model

Labskin™ (Innovenn Ltd.), a three dimensional (3D) human keratinocyte and fibroblast coculture model, was utilized in this study. Upon arrival, the skin models were removed from the transport medium and placed in the supplied culture medium for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. To assess the effect of Plurogel on a biofilm-infected wound, Labskin was wounded using a sterile scalpel blade, perpendicular to the surface of the skin, and ∼1–3 mm into the Labskin. A sample of Labskin was kept unwounded as a comparison. An overnight culture of S. aureus was diluted to a concentration of 104 CFU/mL. Ten microliters of the S. aureus suspension was then added to the new wounds and the Labskin was incubated for 96 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 before collecting the medium. At 96 h, the medium was changed and the wound biofilm was treated with 0.1 g of either Plurogel or PSSD. An untreated S. aureus biofilm wound control was also set up. The treated Labskins were then incubated for 48 h. Samples (200 μL) of conditioned cell culture medium were collected on days 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6. At the end of the experiment, Labskin was fixed in 10% formalin. To assess biofilm prevention, wounded Labskin models were coated with 0.1 g of Plurogel or PSSD before inoculating the wounds with S. aureus (within a support matrix). The experiment was continued as described above, without the treatment of wound biofilms at 96 h.

Histology

Labskin samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for a minimum of 24 h. Fixed samples were processed in a series of ethanol dehydration steps, and a clearing xylene step to displace residual ethanol and remove fats, and then finally infiltrated with paraffin wax. Samples were embedded in paraffin wax blocks and sectioned (4–6 micron sections) onto slides. Routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Gram staining were performed on all specimens. Stained sections were visualized using the Nikon Eclipse Ci microscope.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The levels of the secreted inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα were detected using a Human IL-6 ELISA kit and a Human TNFα ELISA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, United Kindgom) suitable for serum, plasma, and cell culture supernatants. ELISA was carried out according to manufacturer's instructions.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software. Statistical comparisons between ELISA protein concentration values were performed using the two-way ANOVA.

Results

Effects of Plurogel and PSSD on cell viability

The microscopic images of HDFa cell attachment and morphology after 1-day culture with Plurogel and PSSD are shown in Fig. 1. There were a small number of round and degenerated cells under Plurogel (Fig. 1b), but no detectable morphology changes and reduced growth observed around and away from Plurogel (Fig. 1c). However, there were a number of malformed or degenerated cells with devoid intracytoplasmic granules both under and away from PSSD (Fig. 1d, e). It is clear that cellular viability was reduced in the PSSD treatment group when compared to the DMEM control and non-antimicrobial based Plurogel. The cell images on 7 day posttreatment are shown in Fig. 2. The cells under Plurogel and under and away from PSSD had recovered from day 1 and had began to grow and spread (Fig. 2b–e).

Figure 1.

Microscopic images of HDFa in the direct cellular assay following treatment at 1 day. (a), DMEM (culture medium); (b), under Plurogel; (c), ∼0.2 cm away from Plurogel; (d), under PSSD; (e), ∼0.2 cm away from PSSD; (f), under Triton-100; (g), ∼0.2 cm away from Triton-100. Images taken at × 100 magnification. Scale bar: 50 μm. DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium; HDFa, adult human dermal fibroblasts. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Figure 2.

Microscopic images of HDFa in the direct cellular assay following treatment at 7 days. (a), DMEM (culture medium); (b), under Plurogel; (c), ∼0.2 cm away from Plurogel; (d), under PSSD; (e), ∼0.2 cm away from PSSD; (f), under Triton-100; (g), ∼0.2 cm away from Triton-100. Images taken at × 100 magnification. Scale bar: 50 μm. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

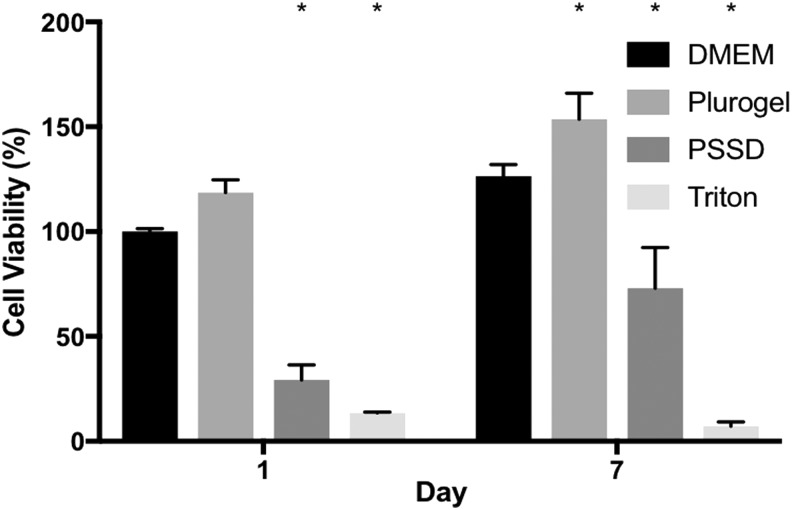

Quantitative cell viability results (Fig. 3) by CyQUANT assay showed that the percentage of cells in the DMEM control had increased from 100% ± 1.47% to 126.49% ± 5.48%, Plurogel treatment had increased from 118.69% ± 6.00% to 153.65% ± 12.42%, and PSSD treatment had increased from 29.21% ± 7.23% to 72.97% ± 19.40%. However, cell viability of Triton-100 treatment, which is a positive control, had decreased from 13.54% ± 0.40% to 7.25% ± 1.95%. The qualitative and quantitative results show that cell viability increased for Pluorgel on day 1 and 7 compared to control culture medium (DMEM). In contrast, the antimicrobial-based wound dressing was shown initially to inhibit HDFa growth; however, cells had recovered by day 7.

Figure 3.

Percentage viability of HDFa following treatment with Plurogel and PSSD in the direct cytotoxicity assay. *versus DMEM p < 0.05.

Effect of Plurogel and Plurogel PSSD on in vitro wound biofilms

Using histological staining techniques (H&E staining and Gram staining) from excised section of the non-wounded and wound sections of the model, it was possible to observe the effects of Plurogel and Plurogel PSSD as a treatment for biofilm-infected wounds. Figure 4a and b represent H&E-stained sections of the excised Labskin before wounding. In Fig. 4c, the wounded control shows clearly wound repair after Plurogel exposure 6 days postwounding, with the formation of epidermal layer present (Fig. 4d). However, this was not evident with the PSSD only (Fig. 4e). The presence of an S. aureus biofilm in the wound was clear and was accompanied with tissue destruction and no distinct cellular morphology (Fig. 4f, g). Pretreating the model with Pluorgel was observed to prevent the biofilm forming (Fig. 4h). While Pluorgel when added to the established biofilm was shown to reduce evidence of the biofilms, there were often areas where biofilms could still be observed (Fig. 4i). However, with biofilms pretreated and posttreated with PSSD, significant biofilm reduction was observed, although on occasions there were often small microcolonies, indicative of biofilm that remained (Fig. 4j, k). Area of black deposits was observed where SSD had deposited, an observation seen with many silver-based wound dressings.

Figure 4.

H&E and Gram staining of Labskin. (a, b) Unwounded H&E-stained control ×40 magnification; (c) Untreated H&E-stained control wound, × 40 magnification; (d) Plurogel-treated H&E-stained wound control ×10 magnification; (e) PSSD-treated H&E-stained wound control, ×10 magnification; (f, g) Staphylococcus aureus biofilm H&E- and Gram-stained control, ×20 magnification; (h) Pretreatment of the wound with Plurogel, H&E and Gram staining, ×40 magnification. No biofilm evidence was observed and the cells remained intact, ×40 magnification; (i) Treatment of S. aureus biofilm with Plurogel, H&E and Gram staining. Still some biofilm present; (j) Pretreatment of the wound with PSSD, ×40 magnification; (k) Treatment of wound with PSSD, ×40 magnification. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Effect of Plurogel and Plurogel PSSD on inflammatory cytokines

The untreated, wounded control consistently secreted IL-6 into the culture medium. The levels of IL-6 were reduced on day 4 due to a medium change; however, levels began to rise up to day 6 (Fig. 5). Similarly, IL-6 levels in the biofilm control and treated biofilms also decreased following medium change; however, these levels did not rise unlike the wounded control. The levels of IL-6 in the PSSD-treated biofilm-infected wound were higher compared with the S. aureus biofilm wound control. However, wounds pretreated with Plurogel and Plurogel-treated biofilm-infected wounds showed further decreases in IL-6 when compared to all treatments and controls.

Figure 5.

The measurement of IL-6 in cell culture supernatant using ELISA. For prevention studies, wounds were coated on day 0 (D0) before inoculation. Wounds were inoculated with S. aureus on D0. Precoated wounds were not treated. For biofilm control, uncoated wounds were treated on day 4 (D4). Samples were tested in duplicate. Error bars represent standard deviation. A significant reduction in IL-6 in comparison to the S. aureus biofilm is represented by * (p≤0.0001). IL-6, interleukin-6. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

TNFα levels were determined on day 1 and 2 postinfection only. An increase in TNFα between day 1 and 2 was observed in the untreated wound biofilm with the concentration increasing from 7.9 to 13.9 pg/mL. Similarly, this was observed with wounds treated with Plurogel, with the concentration increasing from 8.9 pg/mL on day 1 to 18.9 pg/mL on day 2. No significant difference was noted. However, comparison of the untreated wound biofilm and wound biofilm treated with PSSD showed the PSSD-treated samples had significantly lower TNFα secretion on day 1 and 2 with the concentration of 4.6 pg/mL (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

This study was set up to evaluate the efficacy of concentrated surfactant-based wound dressings (antimicrobial [SSD] and non-antimicrobial-based) on wound repair by investigating their effect on cell viability and their ability to suppress IL-6 and TNFα, proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, the wound dressings were evaluated for their ability to suppress the detrimental effects of biofilms in a novel wound biofilm model. Problematic biofilms are well known to affect fibroblast and keratinocyte viability.9,10 Consequently, it is important that wound dressings demonstrate an ability to suppress the effects that biofilms cause and provide an environment that supports enhanced cellular healing. The cytotoxic effects of Plurogel and PSSD were evaluated qualitatively and quantitatively in an HDFa cell model at 1 and 7 days posttreatment. The results on days 1 and 7 outlined in the results have shown that Plurogel did not significantly affect cellular viability, which indicates that Plurogel is potentially noncytotoxic. PSSD precipitously decreased cellular viability at 1 day; however, the cell morphology and proliferation had recovered by day 7 compared to Triton-100, which indicates PSSD is moderately cytotoxic.

A wound biofilm model composed of a keratinocyte epidermis and fibroblast dermal layer was used to evaluate the effects of the surfactant-based wound dressings on biofilms. Using the 3D skin model and histology, we investigated the effect of both the antimicrobial and non-antimicrobial surfactant-based wound dressing on the growth of biofilm using a mature S. aureus biofilm model. In this experiment, the mature biofilm penetrated deep into the wound model, causing tissue destruction. While reduced, when compared to the control, biofilms could still be observed following treatment with Plurogel. However, following the application of PSSD, the biofilm in the wound model and its effects on cells were significantly reduced. Interestingly, no biofilm was observed following pretreatment with Plurogel and PSSD.

The presence of biofilms will increase the levels of proinflammatory cytokines; however, differential effects between planktonic and biofilms on cytokine secretion have been documented.10 In this study, we showed that the presence of Plurogel caused a reduction in the levels of IL-6. This finding has also been reported in the literature.11 Given that the levels of IL-6 in the S. aureus biofilm control were higher compared with the Plurogel-treated wounds, we believe that the Plurogel enhances the cytokine modulating properties of the S. aureus biofilm. In this study, the presence of Plurogel in the wound did not demonstrate the same modulating effect on proinflammatory cytokine TNFα, as seen with IL-6. In comparison, TNFα in supernatant from wounds treated with PSSD showed a significant reduction in concentration, in comparison to the untreated biofilm. TNFα is a proinflammatory cytokine that has been shown to play a role in early wound healing; however, in some cases, it can cause excessive inflammation in wounds, leading to impaired wound healing. Given the reduced levels of TNFα in the supernatant of wounds treated with PSSD, we believe that it has the potential to reduce inflammation caused by biofilm formation. Recent research has shown that other micelle technologies have little effect on the release of IL-6 and IL-8.12

Innovation

We have shown that a non-antimicrobial-based concentrated surfactant-based wound dressing can enhance cellular viability and reduce the presence of planktonic microorganisms in the wound, and effectively reduce the presence of biofilm. Interestingly, in some instances, Plurogel and PSSD appeared to enhance the IL-6 and TNFα cytokine downregulation in the in vitro biofilm model described in this study, and will be the subject of further investigation.

Key Findings.

• A non-antimicrobial surfactant-based wound dressing is noncytotoxic and promotes cellular proliferation.

• An antimicrobial surfactant-based wound dressing can reduce the presence of a mature biofilm.

• A non-antimicrobial-concentrated surfactant-based wound dressing can cause a reduction in the levels of IL-6.

• An antimicrobial-based wound dressing can reduce secretion levels of proinflammatory cytokine TNFα.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 3D

three dimensional

- AHL

N-acyl homoserine lactone

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- HDFa

adult human dermal fibroblasts

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- SSD

silver sulfadiazine

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

We would like to thank Medline Industries and Innoven Ltd. for their support in this study. Funding for these research studies were provided by Medline Industries, Inc.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

The content of this article was expressly written by the authors listed. No ghostwriters were used to write this article.

About the Authors

Anne-Marie Salisbury, PhD, received her degree in Microbiology from the Department of Infection Biology at The University of Liverpool. She has held scientific and laboratory positions in the bacterial diagnostics laboratory and department of medical microbiology at The University of Liverpool. She joined AstraZeneca as a scientist in 2010 and for the last 4 years held the position of senior scientist at Redx Pharma Plc. In 2017, she joined the 5D Health Protection Group Ltd. as a senior Microbiologist and laboratory manager. Dieter Mayer, MD, FEBVS, FAPWCA, completed his studies of medicine in Basel, Switzerland, in 1987. After various postgraduate engagements, in 1996, he passed the Swiss board examination of general surgery and was certified in 2002 by the European Board of Vascular Surgery. This specialization enabled his long grown interest in wound healing to become the center of his work. As Head of Wound Care of the University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, from 2001 to 2016, he established the first dedicated and truly interdisciplinary university wound clinic in Switzerland. As a senior vascular consultant and Assistant Professor, Dr. Mayer cares for all aspects of vascular diseases and wound care at the HFR Hôpital Cantonal Fribourg. Rui Chen, PhD, received his degree in Biomedical Engineering from West China School of Basic Medical Sciences & Forensic Medical at Sichuan University, China. He moved to the United Kingdom in 2001 and worked as postdoctoral research associate at the United Kingdom Centre for Tissue Engineering at The University of Liverpool. He joined 5D Health Protection Group Ltd. as a Research Scientist in 2018. He has worked in the biomedical devices and tissue engineering field for more than 15 years. Steven L. Percival, PhD, held R&D and commercial positions at North West Water Ltd., Phenomenex Ltd., British Textile Technology Group Ltd., and university senior lectureships in medical microbiology early in his career, and was a consultant to numerous government bodies and industrial companies. Following this, he held a senior Director position in global R&D at Aseptica, Inc. and in 2002 was awarded a prestigious Centers for Disease Control (CDC) senior clinical fellowship in Atlanta, USA. Over the last 16 years, he has held numerous Senior Management, Director, and Vice President positions in global R&D in a number of B2C and B2B organizations. In 2015, Steven joined the 5D Health Protection Group Ltd. He is also the Director of the Centre of Excellence in Biofilm Science and Technologies (CEBST) at Liverpool, United Kingdom. He has written over 420 scientific publications and conference abstracts and edited/authored eight textbooks, and provided over 350 presentations worldwide.

References

- 1.Herrick S, Ashcroft G, Ireland G, Horan M, McCollum C, Ferguson M. Up-regulation of elastase in acute wounds of healthy aged humans and chronic venous leg ulcers are associated with matrix degradation. Lab Invest 1997;77:281–288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yager DR, Zhang L-Y, Liang H-X, Diegelmann RF, Cohen IK. Wound fluids from human pressure ulcers contain elevated matrix metalloproteinase levels and activity compared to surgical wound fluids. J Invest Dermatol 1996;107:743–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nwomeh BC, Liang H-X, Cohen IK, Yager DR. MMP-8 is the predominant collagenase in healing wounds and nonhealing ulcers. J Surg Res 1999;81:189–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Percival SL, Hill KE, Williams DW, Hooper SJ, Thomas DW, Costerton JW. A review of the scientific evidence for biofilms in wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2012;20:647–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 2002;15:167–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngo QD, Vickery K, Deva AK. The effect of topical negative pressure on wound biofilms using an in vitro wound model. Wound Repair Regen 2012;20:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González A, Bellenberg S, Mamani S, et al. AHL signaling molecules with a large acyl chain enhance biofilm formation on sulfur and metal sulfides by the bioleaching bacterium Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2013;97:3729–3737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James GA, Swogger E, Wolcott R, et al. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirker KR, Secor PR, James GA, Fleckman P, Olerud JE, Stewart PS. Loss of viability and induction of apoptosis in human keratinocytes exposed to Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in vitro. Wound Repair Regen 2009;17:690–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirker KR, James GA, Fleckman P, Olerud JE, Stewart PS. Differential effects of planktonic and biofilm MRSA on human fibroblasts. Wound Repair Regen 2012;20:253–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao G, Usui ML, Lippman SI, et al. Biofilms and inflammation in chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care 2013;2:389–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu F, Huang H, Gong Y, Li J, Zhang X, Cao Y. Evaluation of in vitro toxicity of polymeric micelles to human endothelial cells under different conditions. Chem Biol Interact 2017;263:46–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]