Abstract

Research on the choices of childcare arrangements in Italy shows the fundamental role of grandparents in providing informal childcare. Therefore, it is important to understand how grandparents provide different types of childcare, especially in terms of differences in their socio-economic, demographic and physical status, jointly with the characteristics of their grandchildren. Grandparents aged 50 and over with at least one non-co-resident grandchild aged 13 years or less were selected from the 2009 Italian household survey. Multilevel multinomial logistic regression models for grandmothers and grandfathers were used to identify the determinants of the probability of providing childcare intensively, occasionally or during school holidays rather than never. The probability of a grandparent providing intensive childcare is significantly reduced by being: male, unmarried, in bad health and with inadequate economic resources. Nevertheless, when analysing the probability of providing childcare occasionally or during holidays, the individual characteristics of grandparents and grandchildren are less significant compared to intensive childcare, meaning that grandparents provide non-intensive care regardless of their individual characteristics, and this is particularly true for grandmothers. Results confirm the fundamental importance of grandparents in providing informal childcare in Italy, and they offer useful information to understand the individual characteristics associated with different types of grandparental childcare.

Keywords: Grandparenthood, Grandparenting, Care provision

Background

In developed countries, increased life expectancy has significant implications for family life. Longer life expectancy means that more children have living grandparents, though this trend could be counterbalanced by a delay in fertility, especially in countries where this phenomenon is particularly pronounced (Tomassini and Wolf 2000). Grandparents play a fundamental role in providing childcare and support to their grandchildren, especially in countries where public services are limited. Past literature demonstrates that in Europe maternal labour force participation is significantly associated with the availability of informal childcare (Aassve et al. 2012a; Arpino et al. 2014; Hamilton and Jenkins 2015; Zamarro 2011). A recent study (Di Gessa et al. 2016a), which analysed cross-national variations in the provision of grandchild care, found that the probability of grandparents being involved in intensive childcare not only depends on individual characteristics but also on the needs of children and on country-level characteristics. It found that grandparents are generally more likely to provide intensive childcare to working mothers in countries where women participate less frequently in the labour force, such as in Italy. Wheelock and Jones (2002) suggest that families often only contemplate the option of mothers entering the workforce if they have access to childcare that they are happy with. Some parents may question formal childcare based on concerns over its quality (Gardiner 2000) and therefore may prefer to turn to grandparents for higher standard support for their children, and this may be particularly true in countries with familistic cultures. Moreover, involvement of grandparents in childcare has been associated with several aspects of family life such as the birth of an additional child (Aassve et al. 2012b; Hank and Kreyenfeld 2003; Jappens and Van Bavel 2011; Liefbroer and Thomese 2013) or after a separation (Attias-Donfut et al. 2005; Bucx et al. 2012; Kalmijn 2013). Previous studies have also stressed the preponderance of women in caring roles (Liefbroer and Thomese 2013; Wall et al. 2001). Such gender differences could be attributed to the differing roles, expectations and desires that grandfathers and grandmothers have with respect to care and family involvement (Di Gessa et al. 2016b).

As mothers are increasingly encouraged to work by EU targets (Commission of the European Communities 2005) and western countries are experiencing higher rates of divorce and relationship breakdown, grandparents may spend even more time in childcare in the future (Glaser et al. 2013). On the other side, trends in labour force participation will also play a major role. The increasing age for women to be eligible for retirement greatly reduces their availability for childcare as grandmothers (Bratti et al. 2016). In 2010 roughly 23% of Italian women aged 55 years (the estimated mean age at grandparenthood for Italian women born in 1945) were employed and likely to remain in the labour market for at least another 5 years because of the increasing age of retirement. These trends suggest that the traditional role of informal support provided by grandmothers is likely to become more difficult to sustain in countries such as Italy (ISTAT, Rapporto annuale 2010).

Given these challenging trends for future involvement of grandparents in childcare, we observe that although the effects of the grandparental role on family lives have already been explored in numerous studies, less attention has been devoted to the determinants of different types of childcare provision in countries where grandparents are more involved in caring for their grandchildren, such as in Italy. Do the determinants usually found significant in previous studies in western countries still hold in a familial context such as Italy? What are the characteristics of grandparents that are more associated with different types of childcare?

The Italian context

Little research has been devoted to the characteristics of grandparents in Italy compared to other western countries, which is surprising given their major role in childcare. There are several reasons why studying the grandparental role in Italy is important. Not only it is a country with modest availability of formal support for children, but it is also a population where some important demographic trends are particularly pronounced, such as reduced and delayed fertility and increased life expectancy. It is therefore important to understand the characteristics of grandparents who provide childcare in a country where the formal provision of support is not particularly pervasive and is scattered within different geographic areas.

Researchers who have investigated family choices on childcare arrangements in Italy tend to agree on the importance of informal childcare provided by grandparents, who sometimes represent the only childcare opportunity for families in terms of affordability or availability (Del Boca et al. 2005; Sarti 2010). According to Del Boca et al. (2005), the presence of a grandmother who lives nearby and in good health is an important explanation for the choice to shift from public to informal childcare, especially when very young children are involved. From 1998 to 2009, the proportion of Italian families receiving informal support in childcare rose by 6% and this increment is particularly evident in families where the mother is in the workforce, according to ISTAT (2010). In the same period, the proportion of families using public services increased from 3.4 to 6.3%, but the proportion of unmet demand for public care has always remained high, especially in the south of Italy, where there is less availability of formal help (ISTAT 2010). Such a context suggests that the role grandparents play in family life is likely to increase significantly. In the Netherlands, Geurts et al. (2014) observed an increasing propensity to provide grandchild care from 23 to 41% between 1992 and 2006. They suggested that the increase could be ascribed to higher maternal employment rates, growth in single motherhood, reduced travel time and a decline in the number of adult children, all factors that are also emerging in Italy. It is also interesting to consider data from the grandchildren’s point of view as a grandparent is often expected to a take care of more than one grandchild, so that only analysing the proportion of grandparents providing childcare could underestimate the real impact of grandparental contribution. The 2011 Multiscopo Aspects of Daily Life survey carried out by ISTAT included a questionnaire for children (0–17 years) investigating who the adults are that take care of them. When children aged 0–13 were not at school or with parents, 54.6% were cared for by a non-co-resident grandparent and 13.7% by a co-resident grandparent. The involvement of non-co-resident grandparents was even greater for grandchildren aged between one and ten (56%). The involvement of co-resident grandparents was significantly greater when grandchildren were younger than one and lower when aged 11 and older. Only 18.4% of children did not need childcare; they tended to be older children (11–13 years) and the youngest (0–2 years). When only children who did not attend kindergarten (more than 73%) were analysed, we found that 46% of them were cared for by grandparents, the highest proportion after mothers. Similarly, when only children who did not attend preschool (4%) were analysed, we observed that one third of them were cared for by grandparents (again second only to mothers). Similar evidence is observed by Di Gessa et al. (2016a), who found using SHARE data that grandparents have a significantly higher probability of providing intensive childcare when their grandchildren are between the ages of three and five (compared to younger grandchildren). In order to focus on the characteristics of grandparents and estimate their propensity to provide more or less intensive childcare, the paper, unlike previous studies, will consider data that collect information on Italian grandparents and grandchildren simultaneously.

Data and methods

The most important data contribution on grandparenting in Italy is the 2009 Multiscopo Family and Social Subjects survey (FSS), carried out by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), which is characterized by a large sample size and a very high response rate (above 80%) as strong points. The survey covers a wide variety of topics, including questions on household structure, demographic background, socio-economic characteristics, housing and life histories. For this study, we have selected grandparents older than 50 years (9447 individuals). As data are collected cross-sectionally, our analysis aims at describing associations (and not causality) between involvement in childcare and the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of grandparents and grandchildren. In addition to the cross-sectional design, it should be noted that due to the structure of the questionnaire, it is not possible to link three generations. (Older people are asked about their offspring and grandchildren, but not using a vertical structure; therefore, it is not possible to link their offspring with their grandchildren.)

The present work aims to analyse how grandparents provide different types of care to their grandchildren, especially in terms of differences in socio-economic, demographic and physical status and the characteristics of grandchildren. As gender differences in the provision of childcare have emerged from the literature (Barnett et al. 2010; Craig and Jenkins 2016; Tomassini and Glaser 2012), we conducted separate analyses by gender, controlling for marital status as married grandfathers may take credit for grandchild care activities provided by their wives.

As the questionnaire does not include data on childcare for co-resident grandchildren, grandparents living with all their grandchildren (2.2% of the total) have been excluded, since we are not able to assess whether co-residence with grandchildren represents an exchange of support from grandparents to their adult children (by helping them with grandchild care) or from adult children to grandparents. Descriptive comparisons between the total sample and grandparents with co-resident grandchildren showed that the latter group tends to be older, sicker and with one child only, suggesting that co-resident grandparents are more likely to be those in need of support. For each grandparent, information on non-co-resident grandchildren was given on up to three grandchildren. For those who had more than three grandchildren living outside the household (66.0% of the total), the questionnaire was restricted to the three living the closest. Since the questionnaire does not investigate childcare provided to grandchildren older than 13, grandparents with all grandchildren aged 14 and above (N = 3031, 32.8%) have been excluded, leaving a sample of 6207 grandparents. In order to create a dataset where each record represents a dyad grandparent–grandchild, the file has been restructured, preserving the information on grandparents, but replicating the record one, two or three times depending on the number of grandchildren living outside the household, obtaining a sample of 10,901 dyads.

Dependent variable

Grandparents are asked to indicate, for up to three grandchildren younger than 14, whether they look after them when their parents work, when they are on school holidays, when their parents have occasional commitments, when their parents go out in their free time, when the grandchildren are sick, or in emergencies and other situations. Since most of the respondents selected more than one of these options in reference to the same grandchild, a variable ‘childcare’ indicating the prevalent typology of grandchild care has been constructed. We assume that the most intensive typology of grandchild care is the one provided when parents work. Then, grandparents providing childcare during school holidays are differentiated, as it is an intensive involvement, but for more limited time periods. In Italy, the summer holiday for preschools and schools is about three months long. During this period, families need to find someone to take care of their children, and grandparents could be the best or even the only solution, even though they might not be intensively involved in childcare during the rest of the year. Moreover, we may expect that older people (especially when wealthy) tend to spend the summer in holiday homes outside the city centres and grandparents and grandchildren could spend some weeks together there while the grandchildren’s parents work. Therefore, four categories are considered for grandchild care: (1) none, (2) when parents work (possibly in combination with other categories) also renamed ‘intensive childcare’, (3) occasionally (when parents have occasional commitments, when they go out in their free time, in emergency situations, when a grandchild is sick or other unspecified situations) and (4) during school holiday periods (possibly in combination with other modalities except when parents work). Whilst a combination of intensive and occasional childcare is quite frequent (confirming the opportunity to consider these grandparents as greatly involved in their role), interactions between intensive childcare and childcare provided during the school holidays are rare (confirming the opportunity to consider the two categories separately).

Independent variables

Two sets of characteristics are selected as covariates, the first related to grandchildren and the second related to grandparents. The first set includes sex, age (recoded in: 0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–10 and 11–13 years, according to the Italian school structure) and proximity to grandparent’s home (with categories: less than one, 1–16, more than 16 kilometres). The proximity classes are recoded according to the international literature that considers ten miles (around 16 km) as a threshold for close distance. We recognise that there might be an endogeneity bias in considering the geographical proximity when explaining intergenerational exchanges, as proximity itself could be a consequence of the need to provide help to other components of the family (Tomassini et al. 2003), but we keep this variable as it could show different effects when different types of grandchild care are considered. Additionally since childcare during school holidays is considered, it is possible that grandparents living far away may provide help when children are not at school. The second set of covariates related to grandparents includes sex, age (recoded in age classes 50–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79 and 80+), marital status (recoded as married, separated/divorced or single and widowed grandparents), region (recoded as north, centre and south), number of grandchildren and whether grandparents have at least one different co-resident grandchild. Age classes are preferred to the continuous variable since they enable a better understanding of the differences in the grandparental propensity for the provision of childcare. We group categories ‘single’, ‘separated’ and ‘divorced’ for marital status since their percentages were quite small. Socio-economic status (SES) is also considered. Since distribution of educational level shows a low percentage of grandparents with tertiary education, we recode it as secondary school or higher versus compulsory schooling only. The majority of grandparents are retired, so we recode working status as employed versus not employed. Self-reported evaluation of the economic resources of the family in the last 12 months, with original categories: ‘excellent’, ‘adequate’, ‘lacking’, ‘absolutely insufficient’ are recoded as ‘at least adequate’ versus ‘inadequate or insufficient’. (Few grandparents described their economic resources as ‘excellent’ or ‘absolutely insufficient’.) The role of working status may again have a possible endogenous effect: Grandparents may decide to retire early from the workplace in order to support their offspring with grandchild care (Lumsdaine and Vermeer 2015). Socio-economic status (education and income) may have both a direct and an indirect effect on grandchild care. Several national studies show that grandparents with lower education are more likely to care for their grandchildren, especially in terms of co-residence without their offspring (the “skipped” generation households), while mixed results have been found for care to non-co-resident grandchildren (Baydar and Brooks-Gunn 1998; Fuller-Thomson et al. 1997; Minkler and Fuller-Thomson 2005; Luo et al. 2012; Glaser et al. 2013).

Finally, the presence of long-term limiting illnesses, coded as ‘absent’, ‘mild’ or ‘severe’, is used as a health indicator. Despite the questionnaire also including a question on self-perceived health status, we included an objective health indicator in the analysis since it may better indicate the ability of grandparents to perform daily activities.

Statistical multivariate models

The outcome variable of the multivariate analysis is the probability of providing grandchild care intensively, occasionally, during the holidays or never. Because of the clustered structure of the data with more grandchildren per grandparent, the observations were independent across groups, but not within group, which means that grandchildren can be considered as independent when related to different grandparents, but not when related to the same grandparent. The most appropriate method to adopt in such a framework is a multilevel modelling approach, which produces less biased estimates for the upper-level covariates, as standard errors are corrected accordingly (Snijders and Bosker 1999). By using a random intercepts model, we assume that the intercept varies between grandparents, but that the slope is constant. Therefore, as the outcome is categorical and there is not a proper order among the categories considered, the model chosen was a multilevel multinomial logistic regression with ‘never providing childcare’ as a reference category. The covariates used in the model were all categorical, except for number of grandchildren. All tests were considered significant at a 5% level, and all analyses were performed using GLLAMM (Generalized Linear Latent And Mixed Models) (Rabe-Hesketh et al. 2004), which is a package available in STATA (release 12.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX). We performed a joint model for both sexes and two separate ones for grandmothers and grandfathers to assess gender differences in the association of our variables with the outcome.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of grandparents

Table 1 shows the descriptives for the respondents. Grandparents significantly differ by gender for SES and marital status: males are more likely than females to be higher educated, employed, with at least adequate economic resources, having their own income or married. Mean number of grandchildren is significantly higher among grandmothers (equal to three grandchildren) than grandfathers (2.8 grandchildren). At the time of the interview, the proportion of grandparents with one, two and three or more grandchildren less than 14 years is, respectively, 46.1, 32.3 and 21.7%. This means that there are 2859 people who report data on one grandchild, 2002 on two grandchildren (4004 dyads) and 1346 on three grandchildren (4038 dyads).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of grandparents by gender

| Total (N = 6207) | Male (N = 2784) | Female (N = 3423) | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (±standard deviation) | 66.7 (± 8.4) | 67.8 (± 8.2) | 65.8 (± 8.4) | *** |

| % With a diploma or higher | 20.2 | 23.3 | 17.7 | *** |

| % Employed | 14.0 | 20.6 | 8.7 | *** |

| % Having one’s own income | 81.6 | 97.7 | 68.5 | *** |

| % Having at least adequate economic resources | 62.2 | 63.8 | 60.9 | * |

| % Married | 78.4 | 89.1 | 69.8 | *** |

| % Widowed | 16.0 | 6.0 | 24.1 | |

| % Separated, divorced or single | 5.6 | 5.0 | 6.1 | |

| % With a marital disruption in the last 3 years | 3.3 | 2.1 | 4.3 | *** |

| % Chronic illness | 33.7 | 34.3 | 33.2 | Not significant |

| % Any long-term limiting illness | 35.8 | 34.8 | 36.6 | Not significant |

| % North | 40.9 | 39.9 | 41.7 | Not significant |

| % Centre | 18.9 | 19.4 | 18.5 | |

| % South | 40.2 | 40.7 | 39.8 | |

| Mean number of living children (±standard deviation) | 2.4 (± 1.1) | 2.4 (± 1.1) | 2.4 (± 1.1) | Not significant |

| Mean number of grandchildren (±standard deviation) | 2.9 (± 2.3) | 2.8 (± 2.2) | 3.0 (± 2.3) | *** |

Level of significance associated with the Pearson Chi-squared test for frequencies and Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.001

Table 2 shows that less than a half of grandchildren are cared for by grandparents occasionally (42.6%), 30.6% are cared for by grandparents when parents work, 17.7% never and 9.1% during the school holidays. Grandchildren never cared by grandparents are mostly those aged between 0–1 and those aged 11–13. Grandchildren aged 1–2 years are generally looked after by grandparents when parents work and occasionally, such as when grandchildren are in preschool. The overall proportion of grandparents who stay with grandchildren during the holidays does not significantly vary by grandchildren’s age.

Table 2.

Grandchild care received from grandparents by typology and classes of age of grandchildren (percentage values)

| 0 years | 1–2 years | 3–5 years | 6–10 years | 11–13 years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | 24.9 | 15.7 | 15.8 | 17.8 | 21.2 | 17.7 |

| When parents work | 20.2 | 31.6 | 33.4 | 30.4 | 27.6 | 30.6 |

| Occasionally | 47.3 | 43.8 | 42.7 | 41.8 | 42.1 | 42.6 |

| During the holidays | 7.6 | 8.9 | 8.2 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 9.1 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table’s percentages are referred to grandparents–grandchildren dyads (N = 10,901)

Multivariate results

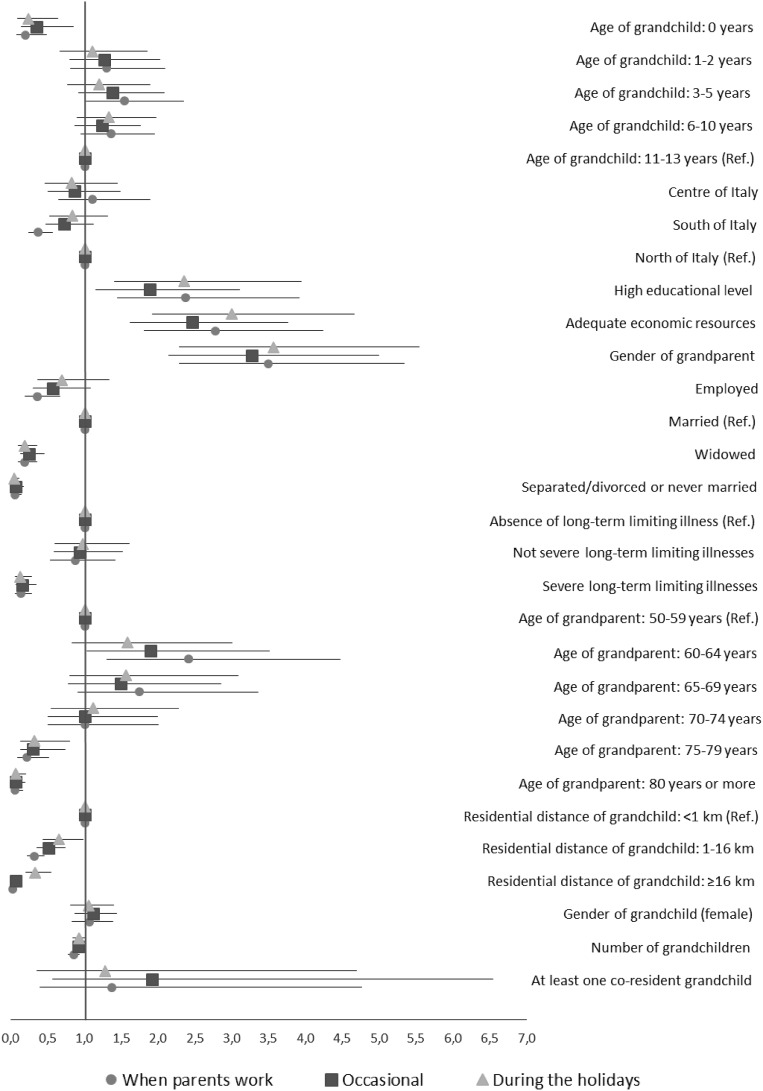

Figure 1 shows the results of the multinomial model estimating the probability of providing grandchild care when parents work, occasionally or during the school holidays rather than never (reference category).

Fig. 1.

Relative risk ratios (RRR) and 95% confidence intervals of providing different typologies of childcare among all grandparents

Regarding intensive childcare, we observe a small but significantly higher probability for grandparents with grandchildren aged between 3 and 5 years (compared to those aged 11–13). Conversely, grandparents are significantly less involved if grandchildren are less than 1 year old. They are also significantly less involved if they live in the south of Italy. We find a significantly higher probability of providing intensive childcare for grandparents with higher education and good economic resources. Gender has the strongest impact on the probability of providing intensive childcare. Grandmothers are more than three times more likely to provide intensive childcare than grandfathers. Probability of grandchild care is instead significantly lower if grandparents are unmarried, employed or if they have severe health problems. The provision of intensive childcare is significantly higher when grandparents are aged 60–64 (when compared to younger age groups), and it decreases again in advanced age. There is also a strong association with proximity to grandchildren, confirming the tendency of Italian families to live close that is associated with intergenerational transfers of support. Moreover, the higher the number of total grandchildren, the lower the probability of grandparental childcare that can be dedicated to each of them, meaning that a grandparent with a large number of grandchildren may find it difficult to support the selected grandchild. Having a co-resident grandchild does not significantly affect the probability of care for another grandchild living outside the household.

Considering the probability of providing occasional childcare, variables related to grandparents are less significant, as grandparents are more involved at this less intensive level regardless of their characteristics. Age of grandchild (with the exception of the category ‘less than 1 year’), geographical region and employment status become not significant. Conversely, variables remaining significant are education, economic status, grandparental gender, marital status, health, advanced age of grandparents, grandchild’s age and proximity. In particular, grandparents are less likely to provide occasional childcare if they have a lower educational level, inadequate economic resources, are male, unmarried, with severe long-term limiting illness, older than 74, living far from their grandchildren or if the grandchild is less than 1 year of age.

Finally, childcare provided during the school holidays again presents less variability among grandparents with different socio-demographic characteristics. The probability is significantly lower for grandparents with fewer economic resources, unmarried, with severe long-term limiting illness, older than 74 or living far away from the grandchild. The effect of proximity to grandchildren is weaker compared to the other categories of childcare, suggesting that grandparents tend to provide childcare at least during some periods of the year even to those grandchildren they are not usually involved with.

In order to explore gender differences in the association of the covariates with the dependent variable, two separated analyses were conducted (Table 3). As far as grandmothers were concerned, results are very similar to those from the full sample, with the exception of employment status, as well as being unmarried, and grandchild age class between 3 and 5 years, which have no effect in predicting the probability of providing intensive childcare. The probability of grandfathers providing intensive childcare does not differ by educational level and number of grandchildren, in contrast with grandmothers. The probability of providing intensive childcare does not significantly change when grandchildren are between 3 and 5 years old (in contrast with the total sample). On the probability of providing occasional childcare, significant differences by marital status were observed for grandfathers (with a strongly lower probability of caring for grandchildren when unmarried), while this difference was not found for grandmothers, who share the same probability of providing grandchild care by marital status. Finally, grandfathers are equally involved in grandchild care during the school holidays independent of the age of the grandchild and their educational level (while grandmothers are less likely to provide childcare during the holidays if they have a lower educational level, as already observed for the whole sample).

Table 3.

Relative risk ratios (and standard errors) of providing different typologies of childcare among grandmothers and grandfathers

| Grandmothers | Grandfathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| When parents work | Occasional | During the holidays | When parents work | Occasional | During the holidays | |

| Age of grandchild: 0 years | 0.19 (0.121)** | 0.39 (0.232) | 0.24 (0.162)* | 0.18 (0.132)* | 0.29 (0.210) | 0.22 (0.177) |

| Age of grandchild: 1–2 years | 1.27 (0.397) | 1.23 (0.378) | 1.10 (0.372) | 1.31 (0.510) | 1.33 (0.508) | 1.12 (0.467) |

| Age of grandchild: 3–5 years | 1.68 (0.464) | 1.53 (0.415) | 1.27 (0.383) | 1.34 (0.461) | 1.19 (0.402) | 1.07 (0.394) |

| Age of grandchild: 6–10 years | 1.53 (0.359) | 1.39 (0.318) | 1.48 (0.378) | 1.12 (0.338) | 1.03 (0.301) | 1.11 (0.355) |

| Age of grandchild: 11–13 years | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Centre of Italy | 1.19 (0.408) | 1.01 (0.343) | 0.94 (0.341) | 0.98 (0.451) | 0.71 (0.324) | 0.68 (0.326) |

| South of Italy | 0.39 (0.109)** | 0.80 (0.221) | 0.85 (0.246) | 0.31 (0.122)** | 0.62 (0.240) | 0.74 (0.294) |

| North of Italy | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| High educational level | 2.53 (0.859)** | 1.73 (0.583) | 2.26 (0.795)* | 1.67 (0.676) | 1.58 (0.638) | 1.96 (0.812) |

| Adequate economic resources | 3.32 (0.863)*** | 2.80 (0.722)*** | 3.67 (1.000)*** | 2.34 (0.881)* | 2.21 (0.829)* | 2.38 (0.923)* |

| Employed | 0.69 (0.331) | 1.17 (0.560) | 1.01 (0.505) | 0.29 (0.149)* | 0.44 (0.224) | 0.73 (0.383) |

| Married | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Widowed | 0.51 (0.161)* | 0.62 (0.194) | 0.46 (0.151)* | 0.02 (0.015)*** | 0.04 (0.030)*** | 0.04 (0.030)*** |

| Separated/divorced or never married | 0.42 (0.218) | 0.56 (0.288) | 0.30 (0.167)* | 0.00 (0.003)*** | 0.00 (0.004)*** | 0.00 (0.004)*** |

| Absence of long-term limiting illness | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Not severe long-term limiting illnesses | 1.29 (0.376) | 1.22 (0.353) | 1.34 (0.406) | 0.50 (0.213) | 0.64 (0.271) | 0.64 (0.280) |

| Severe long-term limiting illnesses | 0.20 (0.089)*** | 0.21 (0.093)*** | 0.23 (0.107)** | 0.12 (0.083)** | 0.17 (0.115)** | 0.09 (0.064)** |

| Age of grandparent: 50–59 years | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Age of grandparent: 60–64 years | 2.38 (0.875)* | 1.82 (0.665) | 1.29 (0.496) | 3.69 (2.932) | 2.98 (2.357) | 3.42 (2.765) |

| Age of grandparent: 65–69 years | 1.11 (0.424) | 1.08 (0.411) | 0.90 (0.358) | 5.33 (4.426)* | 3.72 (3.079) | 6.17 (5.212)* |

| Age of grandparent: 70–74 years | 0.55 (0.228) | 0.64 (0.260) | 0.53 (0.226) | 3.05 (2.619) | 2.49 (2.135) | 4.73 (4.141) |

| Age of grandparent: 75–79 years | 0.07 (0.044)*** | 0.11 (0.070)*** | 0.10 (0.066)*** | 0.81 (0.745) | 0.99 (0.907) | 1.58 (1.481) |

| Age of grandparent: 80 years or more | 0.03 (0.019)*** | 0.05 (0.030)*** | 0.03 (0.022)*** | 0.11 (0.128) | 0.10 (0.113)* | 0.19 (0.215) |

| Residential distance of grandchild: < 1 km | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Residential distance of grandchild: 1–16 km | 0.29 (0.072)*** | 0.50 (0.120)** | 0.58 (0.154)* | 0.34 (0.106)** | 0.54 (0.165)* | 0.79 (0.263) |

| Residential distance of grandchild: ≥ 16 km | 0.02 (0.006)*** | 0.07 (0.022)*** | 0.33 (0.108)** | 0.02 (0.009)*** | 0.08 (0.031)*** | 0.44 (0.178)* |

| Gender of grandchild (female) | 0.99 (0.168) | 0.99 (0.166) | 0.92 (0.170) | 1.21 (0.253) | 1.32 (0.272) | 1.30 (0.290) |

| Number of grandchildren | 0.83 (0.048)** | 0.89 (0.051)* | 0.89 (0.054) | 0.88 (0.088) | 0.95 (0.094) | 0.97 (0.098) |

| At least one co-resident grandchild | 1.11 (0.818) | 1.21 (0.875) | 1.02 (0.783) | 2.59 (2.694) | 5.26 (5.362) | 2.23 (2.447) |

| Intercept | 467.96 (355.951)*** | 319.35 (241.327)*** | 45.81 (36.031)*** | 324.46 (369.553)*** | 207.28 (234.828)*** | 12.22 (14.243)* |

Ref. reference category

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.001

Discussion

An innovative element of the present paper is the choice to focus on the determinants of providing different types of grandchild care. While earlier related literature in Italy has focused on the association between the availability of informal childcare provided by grandparents and family choices about fertility and childcare arrangements, the determinants of the probability of grandparents providing childcare remained underexplored. The classification of the outcome in different typologies of childcare (i.e. when parents work, occasionally, during school holidays) enables a clearer understanding of these determinants on the outcome, especially for school holiday arrangements which is a novel aspect of this paper. For all the types of grandchild care, some determinants that have proved significant in past international literature such as sex, health, old age, proximity and age of the grandchild, were confirmed in this analysis.

Some interesting variations though emerged when different typologies of childcare were considered, reaffirming the importance of not considering childcare as a unique category. Firstly there are fewer variables associated with the probability of providing childcare occasionally or not regularly (i.e. during the school holidays) compared to intensively, as grandparents are more likely to be involved regardless of their individual characteristics. We observed that among women, marital status does not have a significant effect on occasional childcare, indicating the willingness to support adult children at least in some situations even if a marital disruption has occurred. This is not true for grandfathers that are significantly less likely to provide grandchild care when unmarried. These results may suggest that many married grandfathers probably carry out their role alongside their spouses, as already found in previous research (Craig and Jenkins 2016). Tomassini and Glaser (2012) found that when unmarried grandparents are considered, the real gender role in grandparenting is revealed, showing a significantly lower involvement by unmarried men. Being still at work significantly reduces the probability of providing intensive childcare, but it is not significant for grandmothers when the activity of caregiving is not regular: Grandmothers may be asked to help their daughters and sons in childcare even if they are still working. Again, while the presence of severe health problems is significantly associated with a lower provision of childcare, a mild presence of health problems does not have a significant effect. The likelihood of providing childcare also changes with grandparental age in different ways according to the intensity of the engagement. Grandparents providing childcare when parents work are significantly more involved when they are 60–64 years old when compared to younger grandparents or to those over 75. When childcare is less intensive, grandparents are still less likely to provide childcare only when older than 75.

Some findings are particularly related to the Italian context. For all grandparents, the probability of being actively involved is significantly increased by having an adequate economic status and higher educational level (even when regular and intensive childcare is concerned, in contrast with previous European studies). Such a significant role of socio-economic status could suggest that wealthier and higher educated grandparents tend to have wealthier and higher educated offspring, who are more likely to be employed and subsequently in need of their parents’ help. Moreover, it was tested that the probability of having the presence of private domestic help for grandparents with at least adequate economic resources is significantly higher compared to those with insufficient resources (15.3 vs. 3.8%, p < 0.001), so that they would have more time for their grandchildren. This is in line with Luo et al. (2012) who found that higher educated grandparents have a lower probability of starting co-residential grandchild care, but they are more likely than lower educated grandparents to start and continue intensive non-residential care. Additionally, a striking effect of geographical region on the probability of providing intensive childcare was found, with higher levels among grandparents living in the north and the centre of Italy explained by a lower female employment rate in the south.1 This explanation seems to be confirmed as the likelihood of providing help occasionally and during the school holidays by grandparents does not significantly vary by region. Italian grandparents are more involved in intensive grandchild care when grandchildren are between the ages of three and five (preschool age), and they are significantly less involved when grandchildren are in their first year, as also observed by Di Gessa et al. (2016a). This is explained by the availability to parents (mostly mothers) of longer maternity leave compared to other European countries. According to the Institute of National Welfare (INPS, ‘Istituto Nazionale Previdenza Sociale’), mandatory maternal leave for mothers can be extended for 4 months after childbirth2; mothers can also benefit from reduced working hours3 for breastfeeding. Children’s age at admission to kindergarten is 3 months, but the scarce and geographically uneven availability of places leads to the exclusion of the majority of children even when eligible so that mothers take advantage of all possible leave in the child’s first year [only 12.9% of children aged 0–2 had access to public socio-educational services in 2013–2014 according to ISTAT (2016)].

Major limitations of the present study regard firstly the lack of information on grandchildren’s parents, which limits comparison with previous studies. Being able to link the three generations would offer the opportunity to consider further variables that may be relevant to the probability of grandparental childcare. Another limitation is the cross-sectional structure, so it is not possible to correct for potential endogeneity biases resulting from reverse relationships between grandchild care and individual characteristics. Therefore, our results aim at describing significant relationships between involvement in grandchild care and the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of grandparents and grandchildren, and not at assessing causality.

Even with such limitations, our study has several important policy implications. The theme of increasing age at retirement may threaten the availability of grandparental intensive childcare, depriving households of an important source of flexible, low-cost childcare and having potential negative consequences for the employment rates of women with children. These findings suggest that policies aimed at prolonging working life may need to consider grandchild care responsibilities as an offsetting factor while those policies focused on grandchild care may also affect the composition of the older workforce. In the USA, Lumsdaine and Vermeer (2015) explored the relationship between caring for grandchildren and the timing of women’s retirement, finding that the arrival of a new grandchild is associated with a significant increase in the risk of retirement. Such a result seems to confirm the middle generation’s needs in terms of informal childcare and highlights the persisting conflict for young grandparents between caring for grandchildren and labour force participation. This study confirms that the amount of time spent by older people looking after grandchildren is not trivial. Without this provision of grandparental childcare, in particular when parents work, these services would need to be bought in the market, or mothers could be discouraged from participating in the labour force, so the economic and social value of help from grandparents is increasingly relevant (Croda and Gonzalez-Chapela 2005). Our findings show out that the likelihood of providing grandchild care is threatened by marital dissolutions (Separations are increasing among older people in Italy) and by participation in the labour force (also increasing due to the postponement of the age of retirement). The effects of employment are less evident when sporadic childcare is concerned and both these factors are less evident among grandmothers. With rise in the amount of responsibilities experienced by older women, the traditional role of informal support held by grandmothers may become more difficult to preserve. This is particularly important for policy makers since they should carefully evaluate the counterbalance of keeping older people in the labour force and the provision of childcare: The former cannot be achieved without an increase in the supply of formal childcare. Moreover, grandparents who provide childcare to their grandchildren are now older than some decades ago (Leopold and Skopek 2015; Wellard 2011) and this is particularly true in Italy when compared to other European countries (Glaser et al. 2013). Becoming grandparents later in life, although life expectancy is increasing, may be a more challenging task particularly when health does not improve at the same pace as life expectancy. Hence, nowadays grandparents seem to be asked to be actively involved in their role despite having mild health problems. Implications for further research could therefore include an exploration of the boundaries between satisfying involvement for grandparents and the circumstances in which this role could become tiring and stressful.

Footnotes

According to the ISTAT data warehouse, in 2009 the female employment rate was 56.5% in the north, 52% in central Italy and 30.6% in southern Italy.

Maternal leave is allowed for both self-employed and salaried women (for 5 months). During this period, women earn 80% of their usual salary. See http://www.inps.it/portale/default.aspx?itemdir=5804.

Salaried parents and certain categories of self-employed parents can request a further optional period of parental leave which can be taken by the mother and/or the father for up to 6 months. During this parental leave, they earn 30% of their usual salary. See http://www.inps.it/portale/default.aspx?itemdir=5885.

Responsible editors: Karen Glaser and Karsten Hank (guest editors) and Marja J. Aartsen (editor).

References

- Aassve A, Arpino B, Goisis A. Grandparenting and mothers’ labour force participation: a comparative analysis using the generations and gender survey. Demogr Res. 2012;27:53–84. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aassve A, Meroni E, Pronzato C. Grandparenting and childbearing in the extended family. Eur J Popul. 2012;28:499–518. doi: 10.1007/s10680-012-9273-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino B, Pronzato C, Tavares L. The effect of grandparental support on mothers? Labour market participation: an instrumental variable approach. Eur J Popul. 2014;30:369–390. doi: 10.1007/s10680-014-9319-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Attias-Donfut C, Ogg J, Wolff FC. Family support in: health, ageing and retirement in Europe. In: Borsch-Supan A, Brugiavini K, Jurges H, editors. First results from the SHARE. Mannheim: Research Institute for the Economics of Aging; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett MA, Scarambella LV, Neppl TK, Ontai L, Conger RD. Intergenerational relationship quality, gender, and grandparent involvement. Fam Relat. 2010;59:28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Brooks-Gunn J. Profiles of grandmothers who help care for their grandchildren in the United States. Fam Relat. 1998;47:385–393. doi: 10.2307/585269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bratti M, Frattini T, Scervini F (2016) Grandparental availability for child care and maternal employment: pension reform evidence from Italy. IZA discussion paper 9979. 10.2760/32206

- Bucx F, van Wel F, Knijn T. Life course status and exchanges of support between young adults and parents. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:101–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00883.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities . Green paper confronting demographic change: a new solidarity between the generations. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L, Jenkins B. The composition of parents’ and grandparents’ child-care time: gender and generational patterns in activity, multi-tasking and co-presence. Ageing Soc. 2016;36:785–810. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X14001548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croda E, Gonzalez-Chapela J, et al. How do European older adults use their time? In: Borsch-Supan A, et al., editors. Health, ageing and retirement in Europe—first results from the SHARE. Mannheim: Research Institute for the Economics of Aging; 2005. pp. 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca D, Locatelli M, Vuri D. Child-care choices by working mothers: the case of Italy. Rev Econ Househ. 2005;3:453–477. doi: 10.1007/s11150-005-4944-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gessa G, Glaser K, Price D, Ribe E, Tinker A. What drives national differences in intensive grandparental childcare in Europe? J Gerontol B Psycol. 2016;71:141–153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gessa G, Glaser K, Tinker A. The impact of caring for grandchildren on the health of grandparents in Europe: a lifecourse approach. Soc Sci Med. 2016;152:166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M, Driver D. A profile of grandparents raising grandchildren in the United States. Gerontologist. 1997;37:406–411. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner J. Rethinking self-sufficiency: employment, families and welfare. Camb J Econ. 2000;24:671–685. doi: 10.1093/cje/24.6.671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts T, van Tilburg T, Poortman A, Dykstra P. Child care by grandparents: changes between 1992 and 2006. Ageing Soc. 2014;35:1318–1334. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X14000270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser K, Price D, Di Gessa G, Ribe E, Stuchbury R, Tinker A. Grandparenting in Europe: family policy and grandparents’ role in providing childcare. London: Grandparents Plus; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M, Jenkins B. Grandparent childcare and labour market participation in Australia (SPRC Report 14/2015) Melbourne: National Seniors Australia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hank K, Kreyenfeld M. A multilevel analysis of child care and women’s fertility decisions in Western Germany. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65:584–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00584.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT (2010) Rapporto sulla situazione del Paese 2010

- ISTAT (2016) Asili nido e altri servizi socio-educativi per la prima infanzia: il censimento delle unità di offerta e la spesa dei comuni

- Jappens M, Van Bavel J. Regional family norms and childcare by grandparents in Europe. Demogr Res. 2011;27:85–120. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2012.27.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. How mothers allocate support among adult children: evidence from a multiactor survey. J Gerontol B Psycol. 2013;68:268–277. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold T, Skopek J. The demography of grandparenthood: an international profile. Soc Forces. 2015;94:801–832. doi: 10.1093/sf/sov066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC, Thomese F. Child care and child births: the role of grandparents in the Netherlands. J Marriage Fam. 2013;75:403–421. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdaine RL, Vermeer SJC. Retirement timing of women and the role of care responsibilities for grandchildren. Demography. 2015;52:433–454. doi: 10.3386/w20756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, LaPierre TA, Hughes ME, Waite LJ. Grandparents providing care to grandchildren: a population-based study of continuity and change. J Fam Issues. 2012;33:1143–1167. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12438685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Fuller-Thomson E. African American grandparents raising grandchildren: a national study using the census 2000 American Community Survey. J Gerontol B Psychol. 2005;60:S82–S92. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Pickles A. Generalized multilevel structural equation modelling. Psychometrika. 2004;69:167–190. doi: 10.1007/BF02295939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarti R. Who cares for me? Grandparents, nannies and babysitters caring for children in contemporary Italy. Paedagog Hist. 2010;46:789–802. doi: 10.1080/00309230.2010.526347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tomassini C, Glaser K (2012) Unmarried grandparents providing child care in Italy and England: a life-course approach. Paper presented at the Session 14, ‘Ageing and intergenerational relationships’. European Population Conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–16 June

- Tomassini C, Wolf D. Shrinking kin networks in Italy due to sustained low fertility. Eur J Popul. 2000;16:353–372. doi: 10.1023/A:1006408331594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomassini C, Wolf DA, Rosina A. Parental housing assistance and parent-child proximity in Italy. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65:700–715. doi: 10.1023/a:1006408331594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wall K, Aboim S, Cunha V, Vasconcelos P. Families and informal support networks in Portugal: the reproduction of inequality. J Eur Soc Policy. 2001;11:213–233. doi: 10.1177/095892870101100302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wellard S. Doing it all? Grandparents, childcare and employment: an analysis of British Social Attitudes Survey Data from 1998 and 2009. London: Grandparents Plus; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wheelock J, Jones K. ‘Grandparents are the next best thing’: informal childcare for working parents in urban Britain. J Soc Policy. 2002;31:441–463. doi: 10.1017/S0047279402006657. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zamarro G. Family labor participation and child care decisions: the role of grannies. RAND Corp. 2011 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1758938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]