Abstract

Background

Interleukin-13 (IL-13) is a key mediator of T-helper-cell-type-2 (Th-2)-driven asthma, the inhibition of which may improve treatment outcomes. We examined the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity of VR942, a dry-powder formulation containing CDP7766, a high-affinity anti-human-IL-13 antigen-binding antibody fragment being developed for the treatment of asthma.

Methods

We conducted a phase 1, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study at Hammersmith Medicines Research, London, UK, which is now complete. Healthy adults aged 18–50 years (n = 40) were randomized 3:1 to a single inhaled dose of VR942 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, 10, or 20 mg, or placebo. Adults aged 18–50 years who were diagnosed with asthma for ≥6 months before screening, and had forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) values ≥70% of the predicted values at screening (n = 45), were randomized to once-daily inhaled VR942 0.5 or 10 mg, or placebo (2:2:1), or VR942 20 mg or placebo (3:2), for 10 days. All participants were randomized to receive VR942 or placebo based on a randomization list prepared by an independent HMR statistician using SAS® software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The primary outcome was safety and tolerability of VR942 (safety population, defined as all who received at least one dose of VR942 or placebo). This study is listed on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02473939).

Findings

In the VR942 and placebo groups, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 10/30 (33%) and 0/10 (0%) healthy participants, and in 16/29 (55%) and 9/16 (56%) participants with asthma, respectively. Mild intermittent wheezing occurred in 7 participants (VR942 20 mg, n = 4; corresponding placebo, n = 3), resolving spontaneously within 1 h. All TEAEs were mild or moderate; there were no deaths, serious adverse events, or clinically significant changes in vital signs, electrocardiograms, or laboratory parameters. There was no clinically significant immunogenicity, with only one participant with asthma considered positive for treatment-related immunogenicity for CDP7766.

Interpretation

This study, considered to be the only example of a dry powder anti-IL-13 fragment antibody being administered via inhalation, demonstrated that single and repeat doses were well tolerated over a period of up to 10 days in duration. Rapid and durable inhibition of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) (secondary outcome) provided evidence of pharmacological engagement with the IL-13 target in the airways of participants diagnosed with mild asthma. These data, together with the numerical improvements observed for predose FEV1, justify further clinical evaluation of VR942 in a broader population of patients with asthma, and continue to support the development of an inhaled anti-IL-13 antibody fragment as a potential future treatment that is alternative to monoclonal antibodies delivered via the parenteral route.

Funding

Study funding and funding for the medical writing and editorial support for preparation of the manuscript were split equally between the two study co-funders (Vectura Ltd and UCB Pharma).

Keywords: Asthma, Immunotherapy, Interleukin-13, Pharmacodynamics, Safety, Tolerability

Abbreviations: AE, Adverse event; ANCOVA, Analysis of covariance; AUC0–10, Area under the concentration–time curve to postdose day 10; DPI, Dry-powder inhaler; FeNO, Fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1, Forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, Forced vital capacity; HMR, Hammersmith Medicines Research; ICS, Inhaled corticosteroid; IL, Interleukin; IL-4R, Interleukin-4 receptor; MAb, Monoclonal antibody; NO, Nitric oxide; PD, Pharmacodynamic; PK, Pharmacokinetic; ppb, Parts per billion; SABA, Short-acting β2-agonist; SD, Standard deviation; TEAE, Treatment-emergent adverse event

Highlights

-

•

Delivery of dry powder VR942 to the lungs of participants with asthma was well tolerated for up to 10 days of dosing.

-

•

There was no detectable systemic exposure to VR942, and no clinically significant anti-drug-antibody effects were observed.

-

•

Pharmacological engagement of VR942 in the lungs was evidenced by dose-related, rapid and sustained reductions in FeNO.

Research in context.

Effective treatments for patients whose asthma symptoms remain uncontrolled despite corticosteroid therapy are lacking. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-13 (IL-13), play an important role in asthma, and several IL-13 inhibitors have been investigated for the treatment of asthma. Despite IL-13 levels being increased in the lung, these agents have been delivered systemically; the inhaled delivery of VR942 represents an alternative, non-invasive, novel approach offering the potential to deliver greater therapeutic benefit whilst maintaining a good tolerability profile. Results from this study continue to support this rationale and justify continued development of VR942 in a broader population of patients with asthma.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Asthma has a marked impact on patients and society [1], especially when symptoms are uncontrolled [2]. Approximately 300 million people have asthma globally [3], of whom about 10% have severe and persistent disease [4], characterized by uncontrolled symptoms despite treatment with corticosteroids or other controller medications [1].

Cytokines play a cardinal role in the pathogenesis and severity of asthma [5]. One such is interleukin (IL)-13 [6] that signals primarily through the type 2 IL-4 receptor (IL-4R; composed of IL-13Rα1 and IL-4Rα subunits [7]) and contributes to many key features of asthma, including mucus production, eosinophilic airway inflammation, immunoglobulin E synthesis, bronchial fibrosis, and airway hyper-responsiveness [8]. IL-13 is overexpressed in the sputum of patients with asthma, particularly those with severe disease [9], and was recently proposed as a biomarker for evaluating asthma control [10]. Elevated IL-13 levels in patients with uncontrolled asthma despite corticosteroid treatment also support the notion of a potential association between IL-13 and treatment resistance [9], implicating IL-13 signaling as a therapeutic target in severe asthma.

IL-13 stimulates inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase in vitro, driving production and release of NO from lung epithelial cells [11,12]. Parenteral treatment with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that inhibit IL-13 signaling reduces fractional exhaled NO (FeNO) levels [[13], [14], [15]]. Thus, FeNO level may serve as a biomarker for lung inflammation [16]. Clinical studies of anti-IL-13 MAbs have demonstrated FeNO’s potential use as a biomarker for pharmacological activity of these agents in the lungs of patients with mild asthma, including inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-naïve individuals [15,17]. Randomized, placebo-controlled studies with the anti-IL-13 MAbs lebrikizumab and tralokinumab, and the anti-IL-4Rα MAb dupilumab, showed that parenteral administration of these agents reduced exacerbation rates and improved lung function in patients with uncontrolled T-helper-cell-type 2-driven asthma despite corticosteroid therapy, while being well tolerated [13,14,18]. In replicate phase 3 studies in patients with uncontrolled asthma, lebrikizumab and tralokinumab reduced asthma exacerbations in biomarker-high patients compared with placebo, although the reductions did not consistently show statistical significance in all patients across both studies [19,20].

Agents that both inhibit IL-13 signaling and are deliverable directly to the lungs are of particular interest. Pitrakinra, an IL-4 mutein that binds to the IL-4Rα subunit and reduces IL-4- and IL-13-mediated inflammation in patients with asthma, was the first such drug to support a role for inhaled delivery [21]. VR942 (UCB4144; UCB, Brussels, Belgium) is formulated for inhalation as a dry powder and is being developed for the treatment of uncontrolled asthma. It contains CDP7766, a humanized, high-affinity, neutralizing, anti-human-IL-13 antibody fragment that binds to IL-13, preventing binding to the IL-13Rα1 subunit. In cynomolgus monkeys, nebulized CDP7766 was well tolerated at all doses (0.1–60 mg/animal/day) and caused dose-dependent inhibition of bronchoconstriction and reduction in levels of proinflammatory cytokines induced by an inhaled allergen (Ascaris suum), for up to 24 h [22].

Here, we report data from the first-in-human, phase 1, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study, which aimed to assess the safety and tolerability of VR942 in healthy participants and participants with asthma.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This was a two-part, phase 1, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study. In part 1, healthy participants received a single dose of VR942; in part 2, participants with asthma received multiple doses of VR942. The trial was performed at Hammersmith Medicines Research (HMR), London, UK, in compliance with European Union Directives 2001/20/EC and 2005/28/EC, the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004 and current amendments, and the Declaration of Helsinki (Brazil Revision, 2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the Scotland A Research Ethics Committee. All participants gave written informed consent for participation and for data to be entered into The Over Volunteering Prevention System [23]. This study is listed on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02473939).

Eligible for inclusion were men and women (non-child-bearing potential) aged 18–50 years, ≥50 kg in weight, a body mass index of 18.0–31.0 kg/m2, and a peak inspiratory flow rate of ≥60 L/min for ≥2 s. Healthy participants had to have forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) values >80% of the predicted values at screening, based on reference equations [24].

Participants with asthma were required to have a history of asthma (as defined by the Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines [1]) for ≥6 months before screening, FEV1 and FVC values ≥70% of the predicted values at screening (assessed without β2-agonist treatment [no use in the previous 6 hours]) and based on reference equations [24], and an FeNO level ≥35 parts per billion (ppb). Owing to challenges in recruiting ICS-naïve participants, the protocol was amended to include participants receiving stable low-dose ICSs (beclomethasone ≤500 μg/day or equivalent). For those taking ICS, FeNO values at screening and predosing on day 1 had to be within 20% of each other.

Exclusion criteria included current smoker, a smoking history of more than 10 pack-years, respiratory tract infection within 4 weeks of screening, use of prescription or over-the-counter medicines (other than paracetamol) 7 days before trial dosing, and use of a MAb 6 months before dosing. The use of short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs) was permitted; individuals who had used leukotriene antagonists in the 2 weeks before screening or long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) at any time before screening were excluded. See the supplementary appendix for further exclusion criteria.

All participants were randomized to receive VR942 or placebo based on a randomization list prepared by an independent HMR statistician using SAS® software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In part 1, 8 healthy participants were allocated to each VR942 dose group (0.5 mg, 1.0 mg, 5.0 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg) and were randomized 3:1 to receive a single dose of VR942 or placebo. In part 2, 9 participants with asthma were allocated to each of the 0.5 mg and 10 mg groups, and were randomized 2:1 to receive VR942 or placebo; 27 participants were allocated to the 20 mg group and were randomized 3:2 to receive VR942 or placebo.

Placebo and active treatments for each group were identical in appearance. Doses were administered as 1–4 separate inhalations, matched for placebo and active treatment within each cohort. HMR site staff enrolled participants, and all trial personnel, participants, and the study sponsor were blinded to treatment allocation.

2.2. Procedures

VR942 (Vectura Ltd, Chippenham, UK) was administered at nominal doses of 0.5 mg (1 × 0.5 mg inhalation), 1.0 mg (2 × 0.5 mg inhalations), 5.0 mg (1 × 5.0 mg inhalation), 10 mg (2 × 5.0 mg inhalations), and 20 mg (4 × 5.0 mg inhalations). The formulation was contained in a unit-dose blister and delivered via the multidose F1P dry-powder inhaler (DPI; Vectura Ltd, Chippenham, UK). See the supplementary appendix for information about the sentinel approach to dosing.

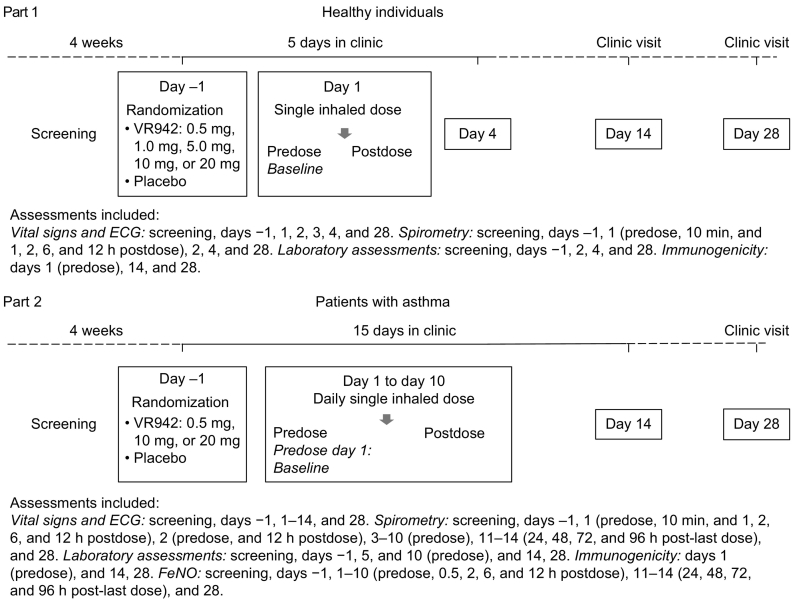

Participants were admitted to the clinic the day before dosing (day −1) following a 4-week screening period. In part 1, healthy participants received a single dose of VR942 or placebo and remained in the clinic until all postdose assessments were complete (72 h postdose, day 4). After the final in-clinic assessment, participants were discharged and returned for follow-up visits on days 14 and 28. In part 2, participants with asthma received once-daily morning doses of VR942 or placebo for 10 consecutive days (days 1–10) and were assessed in clinic up to 96 h after the final dose (day 14) and as outpatients at day 28 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design. ECG: electrocardiogram; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary objective was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of single doses of VR942 (0.5 mg, 1.0 mg, 5.0 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg) in healthy participants, and the safety and tolerability of multiple ascending doses of VR942 (0.5 mg, 10 mg, and 20 mg once daily for 10 days) in participants with asthma. Secondary aims included determination of the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and immunogenicity of CDP7766 (all participants), and the pharmacodynamic (PD) effect of VR942 on FeNO level (participants with asthma).

Vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, and respiratory rate) were recorded, and 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs), physical examinations, spirometry (FEV1 and FVC), pulse oximetry, and laboratory assessments (routine hematology, biochemistry, urinalysis) were performed predose and at specified postdose intervals up to the final follow-up visit (Fig. 1). FEV1 and FVC were measured using a Microlab MK8 spirometer according to ATS/ERS guidelines [25]. See the supplementary appendix for further details regarding the assessment of vital signs and ECGs. Tolerability was assessed throughout the study and included recording of all adverse events (AEs), and comments recorded by HMR site staff on an inhalation checklist regarding participants’ tolerability of VR942 during dosing.

In participants with asthma, FeNO levels were measured at screening and on day −1, days 1–10 (predose, 0.5, 2, 6, and 12 h postdose), days 11–14 (24, 48, 72, and 96 h after the last dose), and day 28 (follow-up). FeNO was measured using a NIOX MINO® analyser according to ATS/ERS guidelines [25]. On days when spirometry was also scheduled at the same time point, the FeNO level was measured first.

Blood samples for PK assessments in part 1 were taken predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 24, 48, and 72 h postdose. In part 2, samples were collected predose and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 h postdose on days 1 and 10, predose on days 2 and 9, and on days 11–14 (at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after the last dose on day 10). A validated ligand plasma binding assay method (quantitation range: 99.6–2000 ng/ml; PRA Health Sciences, Assen, Netherlands) was used to measure free CDP7766. In the assay, CDP7766 present in human serum binds to biotinylated human IL-13 immobilized on streptavidin-coated plates. Bound drug was detected using a goat anti-Human Kappa antibody conjugated to ruthenium SULPHO TAG, and the resulting electrochemiluminescent signal was measured on the Meso Scale Discovery Sector Imager 6000. See the supplementary appendix for further information regarding pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity assessments.

Blood samples for evaluating anti-CDP7766 antibodies were taken from all participants predose on day 1, and on days 14 and 28 after the first dose of VR942 or placebo. Immunogenicity tests were performed by PRA International (Groningen, Netherlands), using a validated assay. With a rabbit monoclonal anti-CDP7766, a sensitivity of 1.22 ng/mL was demonstrated. Further details of the methodology for evaluating anti-CDP7766 antibodies can be found in the supplementary appendix.

2.4. Statistical analyses

To assess safety and tolerability while minimizing the number of participants exposed to VR942, the target sample size was 8 participants per dose group for part 1 (VR942, n = 6; placebo, n = 2) and 9 participants for each of the 0.5 and 10 mg dose groups in part 2 (VR942, n = 6; placebo, n = 3). For the 20 mg dose group in part 2, the target sample size for assessing PD effects was up to 35 participants (VR942, n = 21; placebo, n = 14). This was adjusted (protocol amendment) following a review of data from participants in the VR942 0.5 mg and 10 mg dose groups. The previously assumed common standard deviation (SD) of 30% was reduced to 24%, meaning 25 participants (VR942, n = 15; placebo, n = 10) would be expected to provide ≥80% power to detect a difference of 30% change from baseline in FeNO level between the VR942 and placebo groups, given a 2-sided t-test with a 5% significance level.

Demographic, safety, and tolerability data were summarized descriptively by treatment group (VR942 and pooled placebo) and time point for the safety population (all participants who received at least 1 dose of study treatment). Absolute FeNO values and mean changes from baseline were summarized by VR942 and pooled placebo groups for the PD population (all participants who received at least 1 dose of study treatment and who had at least 1 postdose FeNO measurement recorded). Changes from baseline in FeNO level at 0.5 and 2 h post last-dose on day 10 were compared between the VR942 20 mg and pooled placebo groups using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), adjusting for treatment group and baseline FeNO level. Post hoc ANCOVAs were performed for (1) the same endpoint and time points for the placebo group and all active treatment groups, and (2) changes from baseline in FeNO level predose on day 10 for the placebo group and all active treatment groups. Weighted least-squares means for FeNO values were obtained from the ANCOVA of change from baseline in FeNO area under the concentration–time curve to postdose day 10 (AUC0–10), adjusting for treatment group and baseline FeNO level. AUC0–10 was normalized before analysis by dividing by the time interval from dosing on day 1 to 12 h postdose on day 10 (nominally 9.5 days).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

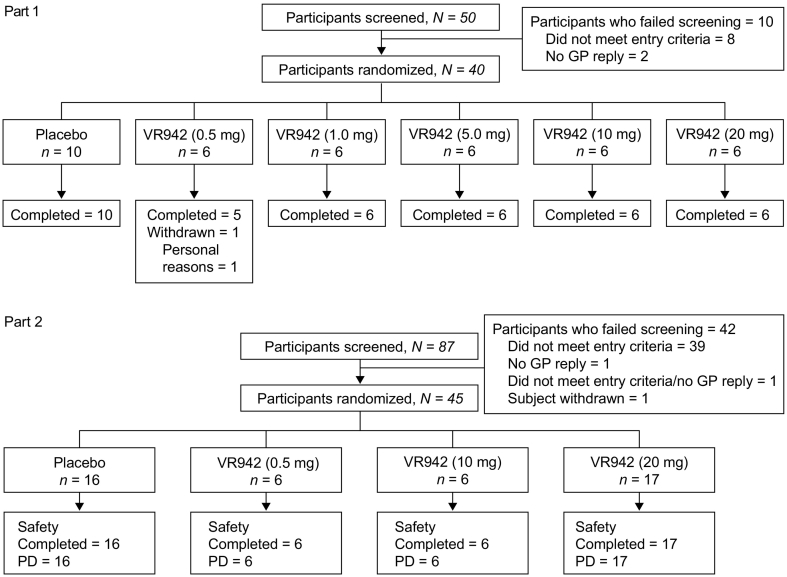

In part 1, 50 healthy individuals were screened for inclusion (May 15, 2015 to July 24, 2015). Of these, 40 were randomized to receive treatment; 1 participant in the VR942 0.5 mg group withdrew from the study on day 2 for personal reasons (Fig. 2). In part 2, 87 patients with asthma were screened for inclusion (June 9, 2015 to March 8, 2016), and 45 were randomized; no participants withdrew (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Trial profile of healthy participants (part 1) and participants with asthma (part 2). GP: general practitioner; PD: pharmacodynamics population.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of healthy participants and those with asthma were similar in the VR942 and placebo groups (Table 1). All randomized healthy participants were male, with a mean ± SD age of 33 ± 9.2 years; all randomized participants with asthma were male, with a mean ± SD age of 30 ± 7.5 years. All participants, except 1 with asthma, were ICS-naïve, and remained so for the duration of the study.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics.

| Characteristic | Healthy participants (N = 40) |

Participants with asthma (N = 45) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 10) |

VR942 |

Placebo (n = 16) |

VR942 |

|||||||

| 0.5 mg (n = 6) |

1 mg (n = 6) |

5 mg (n = 6) |

10 mg (n = 6) |

20 mg (n = 6) |

0.5 mg (n = 6) |

10 mg (n = 6) |

20 mg (n = 17) |

|||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 34 (8.4) | 35 (11.0) | 32 (14.3) | 32 (5.4) | 29 (9.7) | 33 (7.3) | 29 (9.3) | 30 (6.4) | 29 (4.7) | 30 (7.3) |

| Men | 10 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 16 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 17 (100%) |

| Race | ||||||||||

| White | 7 (70.0%) | 4 (66.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 3 (50.0%) | 2 (33.3%) | 5 (83.3%) | 10 (62.5%) | 3 (50.0%) | 5 (83.3%) | 12 (70.6%) |

| Black/African American | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 | 2 (12.5%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 2 (11.8%) |

| Other | 2 (20.0%) | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 | 4 (25.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 23.5 (2.51) | 27.2 (2.35) | 23.0 (3.04) | 23.9 (1.54) | 25.6 (2.56) | 25.1 (1.97) | 24.2 (3.01) | 24.5 (2.61) | 26.0 (3.24) | 24.8 (3.06) |

| Smoking status | ||||||||||

| Former smoker | 4 (40.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 5 (31.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (17.6%) |

| Never smoked | 6 (60.0%) | 5 (83.3%) | 5 (83.3%) | 5 (83.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 11 (68.8%) | 4 (66.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 14 (82.4%) |

| ICS-naïve | 10 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 16 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 16 (94.1%) |

| Spirometry, mean (SD) | ||||||||||

| FEV1 (L) | 4.23 (0.435) | 4.10 (1.012) | 3.80 (0.580) | 4.27 (0.818) | 3.40 (0.318) | 4.27 (0.385) | 3.68 (0.895) | 3.19 (0.435) | 3.71 (0.718) | 3.16 (0.723) |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 106 (8.7) | 100 (17.2) | 94 (9.5) | 107 (16.5) | 89 (4.8) | 102 (10.9) | 89 (17.1) | 78 (10.4) | 86 (11.7) | 77 (13.5) |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.80 (0.045) | 0.81 (0.085) | 0.77 (0.062) | 0.82 (0.041) | 0.80 (0.048) | 0.79 (0.042) | 0.75 (0.081) | 0.68 (0.087) | 0.72 (0.054) | 0.69 (0.072) |

| FeNO (ppb), mean (SD) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 68.1 (35.15) | 79.7 (27.54) | 51.8 (26.78) | 92.6 (61.77) |

BMI: body mass index; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; NA: not applicable; ppb: parts per billion; SD: standard deviation.

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

3.2. Safety assessments

3.2.1. Healthy participants

Following administration of a single dose of VR942 in healthy participants, 18 AEs were reported by 11/30 participants (37%) across all VR942 groups (Table 2). In total, 15 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported by 10/30 participants (33%). Two TEAEs were considered to be related to study medication: mild aphthous ulcer, reported by 1 participant in the VR942 1.0 mg group, and moderate cough, reported by 1 participant in the VR942 10 mg group. All TEAEs were mild or moderate, and included nervous system disorders (n = 4), gastrointestinal disorders (n = 3), musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (n = 2), and respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders (n = 2). There were no AEs or TEAEs in the placebo group and no AEs that led to study withdrawal. None of the vital signs, ECG or laboratory values, or changes during the study were considered to be clinically significant by the investigator. A summary of the vital signs and ECG data can be found in the supplementary appendix.

Table 2.

AEs in healthy participants from predose day 1 to day 28.

| AE | Placebo (n = 10) | VR942 dose |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mg (n = 6) | 1 mg (n = 6) | 5 mg (n = 6) | 10 mg (n = 6) | 20 mg (n = 6) | Total (n = 30) |

||

| Any AE | 0 | 1 (17%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 11 (37%) |

| Any TEAE | 0 | 0 | 3 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 10 (33%) |

| Treatment-related TEAE | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 2 (7%) |

| TEAEs by system order class Nervous system disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (13%) |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 4 (13%) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 1 (3%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 1 (17%) | 3 (10%) |

| Aphthous ulcer | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Toothache | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 1 (3%) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (7%) |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Back pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (33%) | 0 | 2 (7%) |

| Cough | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Rhinorrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| General disorders and administration-site conditions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Pyrexia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Infections and infestations | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 1 (3%) |

| Joint dislocation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 1 (3%) |

AE: adverse event; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

Data are n (%). Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms are used. Participants with at least one AE are counted only once per system organ class and preferred term.

3.2.2. Participants with asthma

Following administration of VR942 0.5–20 mg, 29 AEs were reported by 16/29 participants with asthma (55%), 28 of which were TEAEs (Table 3). In all, 15 AEs in 9/16 participants (56%) were reported in the placebo group, of which 13 were TEAEs. In total, 16 TEAEs were considered by the investigator to be related to study medication. Mild intermittent wheezing was reported by 4 out of 17 participants who received VR942 20 mg and by 3 out of 9 participants in the corresponding placebo group, all of whom received study treatment as 4 separate inhalations. These events were mainly reported on day 1 within 5 min of dosing, and resolved spontaneously within 1 h, although a further 7 episodes of mild, intermittent, and transient wheezing occurred throughout the 10-day dosing period. As on day 1, these events resolved spontaneously. One case of presyncope was reported, which occurred more than 4 h after the first dose of VR942 20 mg and was considered by the investigator to be possibly related to the device owing to the inhalation maneuver used by this participant. Other TEAEs occurring in more than 1 participant in any group were headache and rhinorrhea (Table 3). None of the vital signs, ECG or laboratory values or changes during the study were considered to be clinically significant by the investigator. A summary of the vital signs and ECG data can be found in the supplementary appendix.

Table 3.

AEs in participants with asthma, from predose day 1 to day 28.

| AE | Placebo (n = 16) |

VR942 dose |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mg (n = 6) |

10 mg (n = 6) |

20 mg (n = 17) |

Total (n = 29) |

||

| Any AE | 9 (56%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 11 (65%) | 16 (55%) |

| Any TEAE | 9 (56%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 11 (65%) | 16 (55%) |

| Treatment-related TEAE | 5 (31%) | 2 (33%) | 2 (33%) | 8 (47%) | 12 (41%) |

| Device-related TEAE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%)a | 1 (3%)a |

| TEAEs by system order class | |||||

| Nervous system disorders | 2 (13%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (33%) | 5 (29%) | 8 (28%) |

| Headache | 2 (13%) | 1 (17%) | 2 (33%) | 3 (18%) | 6 (21%) |

| Somnolence | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Presyncope | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Sciatica | 0 | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 4 (25%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 5 (29%) | 6 (21%) |

| Wheezing | 3 (19%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (24%) | 4 (14%) |

| Rhinorrhea | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 1 (6%) | 2 (7%) |

| Oropharyngeal pain | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Sneezing | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| General disorders and administration-site conditions | 2 (13%) | 2 (33%) | 0 | 1 (6%) | 3 (10%) |

| Chest discomfort | 1 (6%) | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Catheter-site pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Catheter-site bruise | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Mouth hemorrhage | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | 2 (13%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Pruritus | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Rash erythematous | 0 | 1 (17%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) |

| Eye disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Eye pruritus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (3%) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Back pain | 1 (6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

AE: adverse event; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

Data are n (%). Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred terms are used. Participants with at least one AE are counted only once per system organ class and preferred term.

Considered to be a consequence of the inhalation maneuver performed by this participant.

There was a numerically greater mean increase in predose FEV1 in participants with asthma in the VR942 0.5 mg and 20 mg groups compared with placebo (mean [SD] increase from baseline to day 14: 0.317 [0.299] L, 0.266 [0.209] L, and 0.109 [0.236] L, respectively; supplementary appendix Table 1). Six out of 17 participants in the VR942 20 mg group and 5 out of 9 in the corresponding placebo group experienced a reduction in FEV1 of more than 10% from predose to 10 min postdose on day 1 (max. reduction of 29% and 30%, respectively); reductions were transient, were associated with mild wheeze (recorded as an AE) in 3 participants in the VR942 20 mg group and 2 receiving placebo, and resolved without treatment.

3.3. PD effects

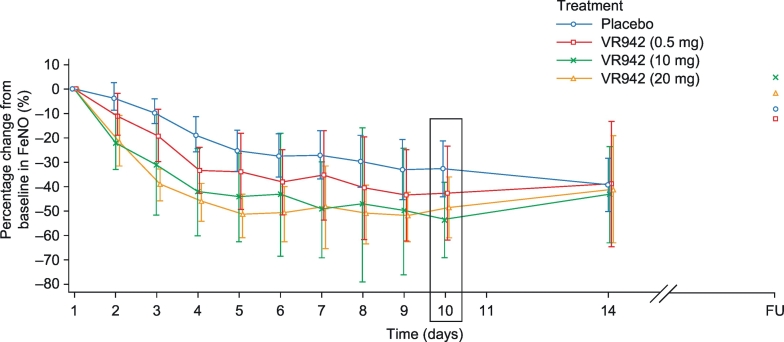

VR942 treatment markedly decreased FeNO levels in participants with asthma. The mean FeNO level decreased by approximately 22% from baseline to predose on day 2 (10 mg and 20 mg groups) compared with a reduction of approximately 4% in the placebo group (Fig. 3). Near-maximal reductions were observed on day 4 predose with VR942 10 mg and 20 mg (approximately 42% and 46% reductions, respectively), and on day 6 predose with placebo (approximately 28% reduction; Fig. 3). In all groups, reductions in mean FeNO level were maintained for 96 h after the final dose on day 10, and returned to baseline after the 14-day no-treatment period.

Fig. 3.

Mean percentage change in FeNO level from baseline to predose in participants with asthma. Placebo n = 16, VR942 0.5 mg n = 6, VR942 10 mg n = 6, VR942 20 mg n = 17. Error bars represent 95% CI. Boxed data (day 10) represent the prespecified analysis timepoint. CI: confidence interval; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FU: follow-up.

Statistically significant reductions were observed when comparing the effects of VR942 20 mg and placebo on FeNO levels from baseline to 0.5 h and 2 h postdose on day 10 (prespecified ANCOVA; p = .015 and p = .028, respectively, for VR942 versus placebo; Table 4). In a post hoc analysis comparing the effects of all active treatments versus placebo at these 2 time points, statistically significant FeNO reductions from baseline were demonstrated for the VR942 10 mg and 20 mg groups versus placebo (p = .010 and p = .016, respectively; Table 4).

Table 4.

Least-squares mean changes in FeNO level from baseline to postdose on day 10, in participants with asthma.

| VR942 dose | Hours postdose, day 10 | Least-squares mean for change from baseline, ppb |

Between-treatment difference for VR942 – placebo (95% CI), ppb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR942 | Placebo (n = 16) | ||||

| Prespecified ANCOVA | |||||

| 20 mg (n = 17) | 0.5 | −48.7 | −36.7 | −12.0 (−21.6, −2.5) | .015 |

| 2 | −45.5 | −33.1 | −12.4 (−23.4, −1.5) | .028 | |

| Post hoc ANCOVA | |||||

| 0.5 mg (n = 6) | 0.5 | −33.7 | −33.6 | −0.1 (−11.5, 11.3) | .986 |

| 2 | −35.5 | −30.3 | −5.2 (−18.3, 7.9) | .428 | |

| 10 mg (n = 6) | 0.5 | −51.1 | −33.6 | −17.5 (−29.0, −6.1) | .004 |

| 2 | −48.0 | −30.3 | −17.6 (−30.8, −4.5) | .010 | |

| 20 mg (n = 17) | 0.5 | −45.5 | −33.6 | −11.9 (−20.5, −3.4) | .007 |

| 2 | −42.5 | −30.3 | −12.1 (−21.9, −2.4) | .016 | |

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; CI: confidence interval; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; ppb: parts per billion.

Values were calculated using an ANCOVA of the change from baseline in FeNO level at each time point for all cohorts, adjusted for treatment group and baseline FeNO level.

Statistically significant reductions in FeNO were seen from baseline to predose on day 10 for the VR942 10 mg and 20 mg groups versus placebo (VR942 10 mg mean between-group difference [95% confidence interval]: −17.5 [−29.5, −5.5] ppb; p = .005; VR942 20 mg: −11.6 [−20.5, −2.7] ppb; p = .012; post hoc ANCOVA; Table 5). No statistically significant changes were observed between VR942 0.5 mg and placebo in either analysis. The change from baseline in FeNO AUC0–10 was significantly greater with VR942 10 mg and 20 mg than with placebo (supplementary appendix Table 2).

Table 5.

Least-squares mean changes in FeNO level from baseline to predose on day 10, in participants with asthma.

| VR942 dose | Least-squares mean for change from baseline, ppb |

Between-treatment difference for VR942 – placebo (95% CI), ppb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR942 | Placebo (n = 16) | |||

| 0.5 mg (n = 6) | −35.0 | −31.1 | −3.8 (−15.8, 8.1) | .518 |

| 10 mg (n = 6) | −48.7 | −31.1 | −17.5 (−29.5, −5.5) | .005 |

| 20 mg (n = 17) | −42.7 | −31.1 | −11.6 (−20.5, −2.7) | .012 |

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; CI: confidence interval; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; ppb: parts per billion.

Values were calculated using an ANCOVA of the change from baseline in FeNO level to predose for all cohorts, adjusted for treatment group and baseline FeNO level.

3.4. PK measurements and immunogenicity

Plasma levels of CDP7766 in healthy participants and in participants with asthma receiving VR942 20 mg were below the lower limit of quantification for the PK analytical assay (<99.6 ng/ml), so the PK analysis could not be performed.

Seven of 40 healthy participants tested positive for CDP7766 antibodies, but none were considered positive for treatment-related immunogenicity; these participants also tested positive predose (inhibition ≥36.5%; an observation not considered unusual), and samples taken on days 14 and 28 did not show an increase of at least fourfold in titer. Of these 7 participants, only 1 had an AE, which was mild in severity (musculoskeletal pain in the right foot).

In all, 9 of 45 participants with asthma tested positive for CDP7766 antibodies: 3/16 (18.8%) in the placebo group, 1/6 (16.7%) in the VR942 10 mg group, and 5/17 (29.4%) in the VR942 20 mg group. Only 1 of these had a negative predose sample (inhibition <36.5%) and was therefore considered positive for treatment-related immunogenicity for CDP7766 (20 mg). The other samples that tested positive predose did not show an increase of at least fourfold in titer on days 14 and 28. The participant considered positive for treatment-related immunogenicity for CDP7766 experienced one AE of mild continuous wheezing on day 1, which started within 3 min of dosing and resolved after 20 min, and one AE of mild intermittent wheezing, which started within 1 min of dosing on day 7 and resolved after 2 days. Of the 8 participants who had a positive predose sample, 6 (placebo, VR942 10 mg and VR942 20 mg all n = 2) experienced one or more AEs, which were all mild or moderate in intensity (headache, n = 4; bruise at canula site, drowsiness, intermittent cough, intermittent wheezing, itchy eyes, oral haemorrhage, pain at canula site, sore throat, all n = 1).

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the safety and tolerability of a single inhaled dose of VR942 in healthy participants (part 1) and the effects of VR942 once-daily dosing for 10 days in participants with asthma receiving SABA treatment only (with 1 exception receiving SABA plus low-dose ICS; part 2). VR942 0.5–20 mg was generally well tolerated in both populations, and rapid, dose-related sustained FeNO reductions were observed for VR942 10 and 20 mg doses in participants with asthma. There were no detrimental effects on predose FEV1 with VR942 treatment relative to placebo, and numerically greater increases in predose FEV1 were observed from baseline for VR942 0.5 and 20 mg compared with placebo.

VR942 was administered directly to the lungs via a unit-dose blister DPI. Safety findings from this study align with findings from phase 2 studies of systemically administered anti-IL-13 MAbs lebrikizumab, tralokinumab, GSK679586, and the anti-IL-4Rα MAb dupilumab, which were also well tolerated [13,18,26,27]. Compared with subcutaneous administration, inhalation may provide a more rapid onset of action at lower doses than systemic treatments and may be suitable for use in a broader range of patients [1]. Systemic exposure to CDP7766 was below the limit of quantification following repeat dosing of VR942 20 mg; further studies are needed to explore whether this translates into a reduced potential for systemic-related AEs.

In participants with asthma, a reduction of over 10% in FEV1 from predose to 10 min postdose on day 1 was reported in 6 participants in the VR942 20 mg group and 5 in the corresponding placebo group. All these FEV1 reductions had returned to normal by 60 min postdose without the need for treatment. The reductions in FEV1 were also associated with mild wheezing in 3 participants in the VR942 20 mg group and 2 receiving placebo, which resolved spontaneously. These decreases may have been due to the mass of powder and/or frequency of inhalations, as participants received study treatment as 4 separate inhalations. Participants in the study had good lung function (FEV1 and FVC >70%); it is therefore possible that reductions in FEV1 may prove more significant in patients with greater functional impairment. Lung function will be monitored in future studies.

Results of studies in similar populations showing that FeNO levels are responsive to anti-IL-13 therapies [15,17,28] and those in which IL-13 stimulates lung epithelial NO production make FeNO an intuitive endpoint for an inhaled treatment. Our analyses showed a dose–response effect for reduction in FeNO level following VR942 treatment, whereby no effect was observed with VR942 0.5 mg compared with placebo in contrast to the rapid reductions in FeNO with VR942 10 mg and 20 mg, which were significantly greater than the effect of placebo and were sustained for up to 96 h post cessation of treatment administration. FeNO reductions have been reported with other anti-IL-13 and anti-IL-4Rα candidates in participants with asthma not using ICS [15,17,28] and in those with uncontrolled asthma [14,19,27,29], where attenuation was associated with improvements in several clinical outcomes, including lung function and annualized exacerbation rates [19,26]. FeNO reductions observed with placebo in this study may have been due to participants being domiciled for the 10-day treatment period, therefore having a lower exposure to lung NO stimuli (e.g., environmental allergens, pollutants) than at home. A similar effect was reported in patients with asthma undergoing alpine rehabilitation, in whom significant reductions in FeNO levels over the first 2 weeks were attributed to house dust mite allergen avoidance [[30], [31], [32]].

We consider this to be the only evaluation of an inhaled anti-IL-13 treatment effect on daily in-clinic FeNO levels. Study limitations include evaluating VR942 treatment in those with mild asthma, and the duration of the study (with regard to establishing the potential for immunogenicity).

In conclusion, this phase 1, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study showed that inhaled VR942 (0.5–20 mg) was generally well tolerated in healthy participants and participants with asthma. We showed a convincing PD effect at 10 mg and 20 mg doses, demonstrating rapid and sustained FeNO reductions greater than those observed with placebo. This supports target engagement of VR942 with IL-13 pathways in the airways of patients with asthma, justifying further clinical evaluation in future trials.

Funding sources

Study funding and funding for the medical writing and editorial support for preparation of the manuscript were split equally between the two study cofunders (Vectura Ltd and UCB Pharma), both of which were involved in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the report. The cofunders had no role in data collection.

Conflicts of interest

GB, MJM, FM, and AS are employees of Vectura Ltd; MJ, PP, FS, PV, MZ, and RP are employees of UCB Pharma. LL is a senior partner of TranScrip LLP. GB, MJM, FM, and AS are shareholders in Vectura Ltd. MB is the owner of HMR, a contract research organization.

Author contributions

GB analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. MB was the principal investigator, conducted the study, and reviewed the protocol and manuscript drafts. MJ provided statistical design, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. LL analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. MJM designed the study, performed literature searching, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. FM designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. PP analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. AS designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. FS designed the study, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. PV analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. MZ designed the study, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts. RP designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript drafts.

Acknowledgments

Many HMR staff helped to carry out the study; in particular, we thank M. Walther and team for recruiting the participants, V. Miller and the team of nurses and technicians for running the study, T. Mitchell and team for data management and statistical analysis, and F. van den Berg and other physicians for caring for the participants. Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Lizzy McAdam-Gray, Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.07.035.

Contributor Information

Gary Burgess, Email: gary.burgess@vectura.com.

Malcolm Boyce, Email: mboyce@hmrlondon.com.

Margaret Jones, Email: Margaret.Jones@ucb.com.

Lars Larsson, Email: lars.larsson@transcrip-partners.com.

Frazer Morgan, Email: frazer.morgan@vectura.com.

Peter Phillips, Email: Peter.Phillips@ucb.com.

Alison Scrimgeour, Email: alison.scrimgeour@vectura.com.

Foteini Strimenopoulou, Email: Foteini.Strimenopoulou@ucb.com.

Pavan Vajjah, Email: Pavan.Vajjah@ucb.com.

Miren Zamacona, Email: Miren.Zamacona@ucb.com.

Roger Palframan, Email: Roger.Palframan@ucb.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material 1

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma GINA Report, global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2017. http://ginasthma.org/2017-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/

- 2.Braido F., Brusselle G., Guastalla D. Determinants and impact of suboptimal asthma control in Europe: the international cross-sectional and longitudinal assessment on asthma Control (LIAISON) study. Respir Res. 2016;17:51. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0374-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global asthma report The burden of asthma. 2014. http://www.globalasthmareport.org/burden/burden.php

- 4.European Respiratory Society European lung whitebook; adult asthma. 2013. http://www.erswhitebook.org/chapters/adult-asthma/

- 5.Kandane-Rathnayake R.K., Tang M.L., Simpson J.A. Adult serum cytokine concentrations and the persistence of asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;161:342–350. doi: 10.1159/000346910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Vries J.E. The role of IL-13 and its receptor in allergy and inflammatory responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:165–169. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagnasco D., Ferrando M., Varricchi G., Passalacqua G., Canonica G.W. A critical evaluation of anti-IL-13 and anti-IL-4 strategies in severe asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2016;170:122–131. doi: 10.1159/000447692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corren J. Role of interleukin-13 in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:415–420. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saha S.K., Berry M.A., Parker D. Increased sputum and bronchial biopsy IL-13 expression in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:685–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsilogianni Z., Hillas G., Bakakos P. Sputum interleukin-13 as a biomarker for the evaluation of asthma control. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:923–931. doi: 10.1111/cea.12729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chibana K., Trudeau J.B., Mustovich A.T. IL-13 induced increases in nitrite levels are primarily driven by increases in inducible nitric oxide synthase as compared with effects on arginases in human primary bronchial epithelial cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:936–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suresh V., Mih J.D., George S.C. Measurement of IL-13-induced iNOS-derived gas phase nitric oxide in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:97–104. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0419OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenzel S., Ford L., Pearlman D. Dupilumab in persistent asthma with elevated eosinophil levels. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2455–2466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corren J., Lemanske R.F., Hanania N.A. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1088–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodsman P., Ashman C., Cahn A. A phase 1, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of an anti-IL-13 monoclonal antibody in healthy subjects and mild asthmatics. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:118–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dweik R.A., Boggs P.B., Erzurum S.C. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184 doi: 10.1164/rccm.9120-11ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noonan M., Korenblat P., Mosesova S. Dose-ranging study of lebrikizumab in asthmatic patients not receiving inhaled steroids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.051. (e12) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piper E., Brightling C., Niven R. A phase II placebo-controlled study of tralokinumab in moderate-to-severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:330–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00223411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanania N.A., Korenblat P., Chapman K.R. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in patients with uncontrolled asthma (LAVOLTA I and LAVOLTA II): replicate, phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:781–796. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30265-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panettieri R.A., Jr., Sjobring U., Peterffy A. Tralokinumab for severe, uncontrolled asthma (STRATOS 1 and STRATOS 2): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:511–525. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoniu S.A. Pitrakinra, a dual IL-4/IL-13 antagonist for the potential treatment of asthma and eczema. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:1286–1294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gozzard N., Lightwood D., Tservistas M. Presented at the European Respiratory Society Annual Congress; Milan, Italy: 2017. Novel inhaled delivery of anti-IL-13 MAb (FAb fragment): Preclinical efficacy in allergic asthma. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyce M., Walther M., Nentwich H., Kirk J., Smith S., Warrington S. TOPS: an internet-based system to prevent healthy subjects from over-volunteering for clinical trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:1019–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1231-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quanjer P.H., Tammeling G.J., Cotes J.E., Pedersen OF, Peslin R., Yernault J.C. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report working party standardization of lung function tests, European community for steel and coal. Official statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J Suppl. 1993;16:5–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:912–930. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Boever E.H., Ashman C., Cahn A.P. Efficacy and safety of an anti-IL-13 mAb in patients with severe asthma: a randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:989–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanania N.A., Noonan M., Corren J. Lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe asthma: pooled data from two randomised placebo-controlled studies. Thorax. 2015;70:748–756. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenzel S., Wilbraham D., Fuller R., Getz E.B., Longphre M. Effect of an interleukin-4 variant on late phase asthmatic response to allergen challenge in asthmatic patients: results of two phase 2a studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1422–1431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenzel S., Castro M., Corren J. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma despite use of medium-to-high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a long-acting beta2 agonist: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal phase 2b dose-ranging trial. Lancet. 2016;388:31–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karagiannidis C., Hense G., Rueckert B. High-altitude climate therapy reduces local airway inflammation and modulates lymphocyte activation. Scand J Immunol. 2006;63:304–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piacentini G.L., Bodini A., Costella S. Allergen avoidance is associated with a fall in exhaled nitric oxide in asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:1323–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huss-Marp J., Kramer U., Eberlein B. Reduced exhaled nitric oxide values in children with asthma after inpatient rehabilitation at high altitude. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:471–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1