Summary

Exosomes in plasma of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients comprise subsets of vesicles derived from various cells. Recently, we separated CD3(+) from CD3(–) exosomes by immune capture. CD3(–) exosomes were largely tumour‐derived (CD44v3+). Both subsets carried immunosuppressive proteins and inhibited functions of human immune cells. The role of these subsets in immune cell reprogramming by the tumour was investigated by focusing on the adenosine pathway components. Spontaneous adenosine production by CD3(+) or CD3(–) exosomes was measured by mass spectrometry, as was the production of adenosine by CD4+CD39+ regulatory T cells (Treg) co‐incubated with these exosomes. The highest level of CD39/CD73 ectoenzymes and of adenosine production was found in CD3(–) exosomes in patients with the stages III/IV HNSCCs). Also, the production of 5′‐AMP and purines was significantly higher in Treg co‐incubated with CD3(–) than CD3(+) exosomes. Consistently, CD26 and adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels were higher in CD3(+) than CD3(–) exosomes. ADA and CD26 levels in CD3(+) exosomes were significantly higher in patients with early (stages I/II) than advanced (stages III/IV) disease. HNSCC patients receiving and responding to photodynamic therapy had increased ADA levels in CD3(+) exosomes with no increase in CD3(–) exosomes. The opposite roles of CD3(+) ADA+CD26+ and CD3(–)CD44v3+ adenosine‐producing exosomes in early versus advanced HNSCC suggest that, like their parent cells, these exosomes serve as surrogates of immune suppression in cancer.

Keywords: adenosine, adenosine deaminase, HNSCC, immunmodulation, T cell‐derived exosomes, tumour‐derived exosomes (TEX)

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) are strongly immunosuppressive, and patients with advanced, metastatic or recurrent disease usually have systemic immune defects [1]. It has been noted that the degree of immune suppression correlates with poor prognosis in HNSCC [2, 3]. The immune system plays a key role in cancer progression, and immune evasion is a recognized hallmark of cancer [4]. Similar to other human cancers, HNSCC have developed multiple ways of escape from the host immune system [5, 6]. These include decreased lymphocyte counts, altered T cell functions, accumulations of regulatory T cells (Treg) in situ and in the periphery, abnormalities in natural killer (NK) cell activities and production of various soluble immunosuppressive factors, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and adenosine [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Among these mechanisms, hypoxia‐driven A2A adenosine receptor (A2AR)‐mediated immune suppression in the tumour microenvironment has emerged as a major barrier to immune therapy of cancer [13]. We have reported recently that exosomes produced by HNSCC cell lines as well as exosomes abundantly present in plasma of patients with HNSCC carry various immunosuppressive molecules, including the components of the adenosine pathway, and deliver them to immune cells, reprogramming their functions [14, 15].

Exosomes are the smallest subset of extracellular vesicles (EVs), ranging in size from 30 to 150 nm that differ from larger (200–500 nm) microvesicles (MVs) by a distinct cellular origin. While exosomes derive from the endocytic compartment of the parent cells, MVs bud off the cell surface [16]. Exosomes are of special interest because their molecular and genetic content resembles that of the parent cell [17]. We reported that exosomes produced by HNSCC cells and those present in HNSCC patients’ plasma carried enzymatically active ectonucleotidases, CD39 and CD73 [14]. In the presence of exogenous ATP, these exosomes produced adenosine [18]. Further, tumour‐derived exosomes (TEX) co‐incubated with T cells, including CD4 + CD39 Treg, induced adenosine production [14]. Exosomes isolated from plasma of cancer patients are a mix of tumour‐ and normal cell‐derived vesicles. Recently, we have reported that approximately 30–50% of exosomes in plasma of HNSCC patients were products of T lymphocytes, as they were CD3(+) [19]. These CD3(+) exosomes from plasma of HNSCC patients carried various immunosuppressive proteins and induced down‐regulation of immune cell functions almost as effectively as CD3(–) exosomes which were enriched in tumour cell‐derived vesicles [19]. The questions arose as to which subset of exosomes [CD3(+) versus CD3(–)] was responsible for reprogramming of immune cells and whether effects of these exosome subsets on immune cells had any impact upon disease activity. The association of the adenosine pathway with exosomes provided an opportunity for addressing this question. Here, we explore the presence and activities of the adenosine pathway components, CD39, CD73, CD26 and adenosine deaminase (ADA), in the CD3(+) T cell‐derived and CD3(–) tumour cell‐enriched exosome fractions from plasma of patients with HNSCC. The data indicate that CD3(+) exosomes produced by T cells carry the ADA/CD26 complex and mediate adenosine degradation in recipient cells. The ADA/CD26‐carrying CD3(+) exosome fractions are more numerous in patients with early‐stage HNSCC. In contrast, CD3(–) tumour cell‐enriched exosomes simultaneously release high levels of adenosine and induce adenosine production in Treg. The CD3(–) exosome levels and their enzymatic function are increased in plasma of patients with stages III/IV disease. Further, the data suggest that the CD3(+) T cell‐derived and CD3(–) TEX‐derived exosomes obtained from the HNSCC patients’ plasma faithfully mirror the functional potential of their parent cells.

Materials and methods

Patients

Randomly collected peripheral blood specimens were obtained from HNSCC patients seen at the UPMC Otolaryngology Clinic between 2015 and 2017. The collection of blood samples and access to clinical data for research were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh (numbers MOD0506140, MOD14090291‐03 and MOD09110344‐12). Additionally, peripheral blood of six healthy controls was obtained as per Institutional Review Board (IRB)‐approved specimens protocol (IRB no. 0403105). In addition, plasma was obtained from five HNSCC patients treated with palliative photodynamic therapy (PDT) at the University of Ulm and the German Army Hospital in Ulm. Blood specimens were collected before therapy as well as 24 h, 7 days and 4–6 weeks after PDT. The collection of blood samples was approved by the local ethics committee (no. 323/14, University of Ulm, Germany).

Table 1 lists clinicopathological characteristics of the patients enrolled into the study. The blood samples were delivered in heparin tubes to the laboratory immediately after collection and were centrifuged at 1000 gfor 10 min. Plasma specimens were stored in 1‐ml aliquots at –80°C and were thawed immediately prior to exosome isolation. Clinicopathological information on the patients treated with PDT can be found in the references [9].

Table 1.

Clinicopathological data

| Patients (n = 14) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤ 62 | 7 | 50 |

| > 62 | 7 | 50 |

| (range = 45–75) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | 86 |

| Female | 2 | 14 |

| Disease status | ||

| AD | 10 | 71 |

| NED | 4 | 29 |

| Primary tumour side | ||

| Oral cavity | 4 | 28·6 |

| Pharynx | 4 | 28·6 |

| Larynx | 6 | 42·8 |

| Tumour stage | ||

| T1 | 3 | 21·4 |

| T2 | 6 | 42·8 |

| T3 | 3 | 21·4 |

| T4 | 2 | 14·3 |

| Nodal status | ||

| N0 | 4 | 28·6 |

| N ≥ 1 | 10 | 71·4 |

| Distant metastasis | ||

| M0 | 0 | 0 |

| UICC stage | ||

| I | 4 | 28·6 |

| II | 4 | 28·6 |

| III | 4 | 28·6 |

| IV | 2 | 14·3 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Yes | 9 | 64·3 |

| No | 5 | 35·7 |

| Tobacco consumption | ||

| Yes | 12 | 85·7 |

| No | 2 | 14·3 |

AD = active disease; NED = no evidence of disease; UICC = Union for International Cancer Control.

Exosome isolation by mini size‐exclusion chromatography (mini‐SEC)

The mini‐SEC method for exosome isolation was established and optimized in our laboratory as described previously [20] (EV‐TRACK ID = EV160007). Briefly, plasma samples were thawed and precleared by centrifugations at 2000 g, then 10 000 g and by ultrafiltration using a 0·22‐μm filter. An aliquot of plasma (1 ml) was placed on a mini‐SEC column and eluted with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS). The fourth void volume fraction (1 ml) enriched in exosomes was collected and concentrated on Vivaspin (VS0152, 300,000 MWCO; Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany), as described previously [20].

Characteristics of plasma‐derived exosomes

Exosomes isolated by mini‐SEC were evaluated for particle numbers and size by qNano (Izon, Christchurch, New Zealand), for morphology by transmission electron microscopy and for cellular origin by Western blots to confirm the presence of endosomal markers (e.g. TSG101) as described previously [14].

Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay and exosome concentration

Protein concentrations of the isolated exosome fractions was determined using a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Exosome capture on magnetic beads

Total plasma exosomes in fraction #4 were separated into CD3(+) and CD3(–) fractions by immunocapture using ExoCap™ streptavidin magnetic beads (MBL International, Woburn, MA, USA), as described [19]. Briefly, exosomes (10 μg/100 μl PBS in 0·5 ml in Eppendorf microfuge tubes) were co‐incubated previously with biotin‐labelled anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (clone Hit3a from Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) adjusted to a concentration of 1 μg for 2 h at room temperature (RT). Next, a 50‐μl aliquot of beads was added, and the tubes were again incubated for 2 h at RT. The uncaptured fraction was removed using a magnet. Samples were washed ×1 with dilution buffer from the kit using a magnet. The captured bead/anti‐CD3antibody/exosome complexes were used for antigen detection by on‐bead flow cytometry as described below.

Flow cytometry for detection of surface proteins on exosomes

For flow cytometry‐based detection of antigens carried by exosomes coupled to beads, the method described by Morales‐Kastresana [21] was modified as described previously by us [15].

Staining of exosome‐on‐bead complexes

Exosomes captured on beads were dispensed into Eppendorf tubes and a fluorochrome‐labelled detection antibody of choice was added to each tube. Exosomes were incubated with antibodies for 30 min at RT on a shaker, washed three times using a magnet and then resuspended in 300 μL of PBS for antigen detection by flow cytometry. The following antibodies were used for detection: anti‐CD39‐fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Biolegend; 328206), anti‐CD73‐allophycocyanin (APC) (Biolegend; 344006) and anti‐CD26‐APC (Biolegend; 302710). The adenosine deaminase antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MS, USA; ab34677) was conjugated using the Lightning‐Link APC Antibody Labeling Kit (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Anti‐CD44v3‐phycoerythrin (PE) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; FAB5088P) was used to detect TEX. Labelled isotype control antibodies recommended by each vendor were used in all cases.

The non‐captured exosome fraction was recaptured with CD63 biotinylated antibody to place exosomes on beads as described previously [15] and stained using the above‐mentioned antibodies for the antigen detection by on‐bead flow cytometry.

In preliminary titration experiments, different concentrations of the fluorochrome‐conjugated detection antibodies and isotype control antibodies were used to determine the optimal conditions for staining and detection of the antigens of interest. The isotype controls were used in all cases. The antibody concentration that gave the highest separation index between the detection antibody and the isotype control upon flow cytometry was selected for all experiments.

Flow cytometry

Antigen detection on exosomes was performed immediately after staining using the Gallios flow cytometer equipped with Kaluza version 1.0 software (Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany). Samples were run for 2 min and approximately 10 000 events were acquired. Gates were set on the bead fraction visible in the forward/side light‐scatter.

When exosomes obtained from plasma of HNSCC patients were analysed by flow cytometry, the lower edge of the ‘positive’ gate was set so that 2% of the isotype control was included in this gate (2 standard deviations from the mean of isotype). As this method detects exosomes bound on beads, the preferable way of presenting the data is relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) = mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of stained sample/MFI of isotype control. The RFI value of 1·0 indicates no staining and values > 1·0 indicate positive staining. The % positive values closely reflect the RFI values, although are not identical to these values. We present both RFI and % positive values to simplify the results of exosome separation into discrete fractions.

Adenosine production by exosomes or CD4+CD39+ regulatory T cells co‐incubated with exosomes

CD4+CD39+ T cells were isolated as described previously [22]. Briefly, Ficoll‐Hypaque gradient centrifugation of freshly obtained buffy coats and negative selection of CD4+ cells was performed [CD4+ T cell isolation kit, #130‐096‐533, magnetic‐activated cell sorting (MACS) Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA]. Next, CD39+ T cells were isolated from the CD4+ T cell population using biotin‐conjugated anti‐CD39 antibodies (#130‐093‐505, MACS; Miltenyi Biotec) and magnetic beads coated with anti‐biotin antibodies (#130‐090‐485, MACS; Miltenyi Biotec). Cell separation was performed using AutoMACS, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Freshly isolated, normal human resting CD4+CD39+ T cells (25 000 cells in 50 μl PBS) were co‐incubated with exosomes (10 μg of total exosome fraction #4, CD3(+) or CD3(–) fraction) isolated from plasma of HNSCC patients as described above. An aliquot of ATP (20 μM) was added to each well and incubated for 1 h [18]. Additionally, exosomes alone (10 μg in 100 μL PBS) were incubated with ATP for 1 h at 5% CO2 at 37°C. Supernatants were collected, centrifuged at 6000 g for 2 min and boiled for an additional 2 min. Concentrations of 5′‐AMP and adenosine (ADO) and their degradation products (inosine, hypoxanthine and xanthine) were measured by mass spectrometry, as described previously [18]. As controls, CD4+CD39+ Treg incubated without ATP and ATP in PBS only were used.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). All data were normalized to 1 ml plasma used for exosome isolation by miniSEC. Scatter‐plots depict means and standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). When data are presented as box‐plots, the bar indicates the median, the box shows the interquartile range (25–75%) and the whiskers extend to ×1·5 the interquartile range. Comparison between continuous variables was performed using the two‐tailed paired t‐test. The P‐value of < 0·05 was used to evaluate significance of the data.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics of HNSCC patients

The clinicopathological data for all HNSCC patients (n = 14) are listed in Table 1. The patients’ mean age was 62 years, and they were predominantly male. Anatomical locations of the primary tumours were: the oral cavity (28·6%), the pharynx (28·6%) and the larynx (42·8%). Ten patients (71%) donated blood at the time of initial diagnosis prior to any therapy. These patients had active disease (AD). Four patients (29%) donated blood after completing curative therapy at the time when they had no evidence of disease (NED), as determined by clinical evaluations. Most patients (64%) presented with an early tumour stage (T1, T2) and 28·6% had a negative nodal status. No patient had distant metastases (100% M0); 57% were UICC stages I or II and 43% were UICC stages III or IV. The majority of patients had the moderate histological differentiation grade by histopathology. Most patients (86%) consumed tobacco and/or alcohol (64%) at the time of diagnosis. None of the patients received immune checkpoint inhibition immunotherapy. The five patients (three female, two males) treated with PDT were all palliative patients with at least one pretreatment. One case was UICC stage II and four cases > UICC stage III. The average age was 65 years (± 11·5).

Separation of total exosomes into CD3(+) and CD3(–) fractions

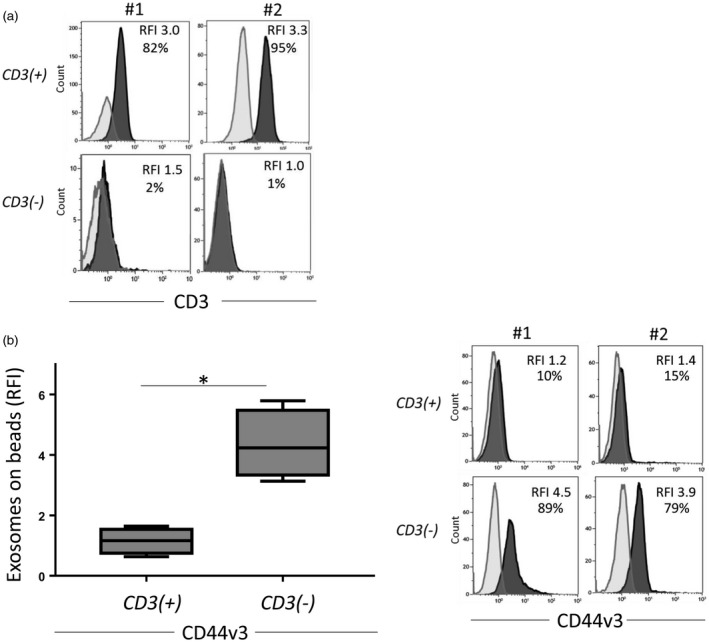

Using immunocapture with anti‐CD3 antibodies, exosomes collected in fraction #4 by mini‐SEC were separated into CD3(+) and CD3(–) fractions, as described previously [19]. The CD3(+) fractions contained from 80 to 97% (3·0 to 4·7 RFI) of CD3(+) exosomes, while CD3(–) fractions contained very few (1–5%) CD3(+) exosomes (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Relative levels of CD3 and CD44v3 on exosomes. (a) Confirmation of exosome capture method: representative histograms from two patients showing high levels of CD3 on exosomes captured with anti‐CD3 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) compared to the non‐captured, CD3(–) exosomes. (b) CD44v3 levels on CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes (n = 5). Note the significantly higher CD44v3 levels on non‐T cell‐derived exosomes (left). Representative histograms showing levels of CD44v3 on exosomes of two patients (right). *P < 0·029.

The origin of exosomes in the CD3(–) fraction

While CD3(+) exosomes originate from T cells, the CD3(–) subset contains exosomes produced by other mononuclear or tissue cells. In the plasma of HNSCC patients obtained prior to surgery, the CD3(–) exosome fractions were expected to be enriched in TEX. To determine the TEX content of CD3(–) fractions, anti‐CD44v3 monoclonal antibody, which detects an antigen highly over‐expressed on HNSCC [23, 24], was used for on‐bead flow cytometry detection. Figure 1b shows a significant enrichment of the CD3(–) fraction in vesicles carrying CD44v3 antigen (mean RFI = 4·3) compared to the CD3(+) fraction (P = 0·029). These data indicate that the majority of CD3(–) exosomes isolated from plasma of HNSCC patients with AD were TEX.

Levels of ectonucleotidases in CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes

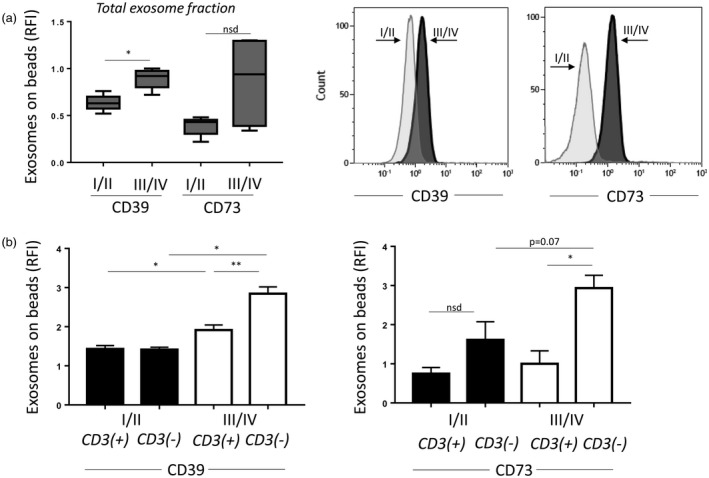

We have shown previously that exosomes from plasma of HNSCC patients carry enzymatically active CD39 and CD73 which convert ATP to ADP/AMP and then to immunosuppressive adenosine [14]. Expecting that exosomes in plasma of patients with advanced (stages III/IV) disease, who are generally immunosuppressed, contain higher levels of CD39/CD73 proteins than exosomes of patients with stages I/II disease, we compared the total exosomes isolated from plasma of these patients for levels of CD39 and CD73 using on‐bead flow cytometry. The data in Fig. 2a show that exosomes derived from the plasma of HNSCC patients with stages III/IV disease carried higher levels of CD39 and CD73 compared to exosomes obtained from patients with stages I/II disease. Next, CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes were compared by on‐bead flow cytometry for the levels of these enzymes. In patients with stages I/II HNSCC, CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes carried equally low levels of CD39 or CD73 proteins (Fig. 2b). In contrast, CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes from plasma of patients with stages III/IV disease differed in that only CD3(–) exosomes had significantly up‐regulated levels of CD73, a rate‐controlling enzyme in the adenosine production pathway. The data suggest that in patients with advanced HNSCC, the CD3(–) exosome subset enriched in TEX becomes largely responsible for adenosine production. However, levels were higher for CD39 and CD73 in both fractions when exosomes derived from the UICC high‐stage patients were compared to low‐stage patients.

Figure 2.

Relative levels of CD39 and CD73 on exosomes. (a) Relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) values of exosome‐bead complexes stained with CD39 or CD73. Note the increased RFI values for CD39 and CD73 in the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) stages III/IV group. On the right, representative histograms showing CD39 and CD73 on exosomes. (b) CD39 or CD73 on CD3(+) or CD3(–) exosomes. Patients were divided by the UICC stage. Note higher levels of CD39 or CD73 in the CD3(–) fraction of the high‐stage patients. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·008.

Enzymatic activity of the adenosine pathway components in CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes

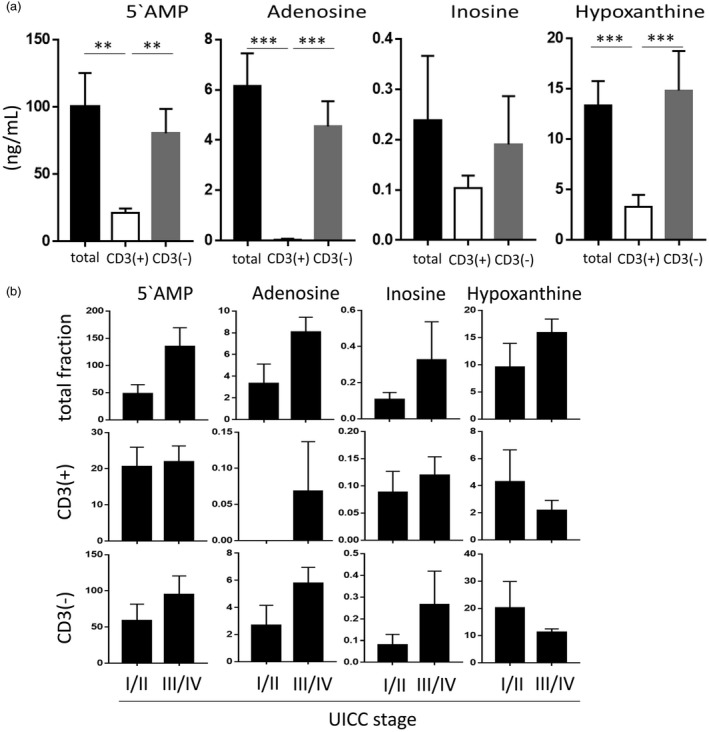

To determine whether the ectonucleotidases and ADA/CD26 tethered to plasma‐derived exosomes retained enzymatic activity, total exosomes as well as the CD3(+) and the CD3(–) fractions were incubated with exogenous ATP alone. Following co‐incubation, mass spectrometry was performed for 5′‐AMP, adenosine, inosine and hypoxanthine. Total exosomes and the CD3(–) TEX‐enriched fractions produced high levels of 5′‐AMP and purines that were comparable to the levels in total exosome fractions (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, no adenosine production was detectable when ATP was added to CD3(+) T cell‐derived exosomes. However, as low levels of inosine and hypoxanthine, the products of adenosine degradation, were detectable, it is likely that adenosine was metabolized rapidly by these exosomes (Fig. 3a). It also appears that CD3(–) exosomes obtained from plasma of HNSCC patients with stages III/IV disease produced higher levels of 5′‐AMP and purines than exosomes of patients with stages I/II disease (Fig. 3b). The data indicate that the components of the adenosine pathway are enzymatically active in exosomes and that the highest adenosine production is seen in the CD3(–) TEX‐enriched exosome fraction.

Figure 3.

5′‐AMP and purine production by exosomes in the presence of exogenous (e) ATP. The exosome fractions of 10 patients were tested. (a) Total exosome fractions show high levels of 5′‐AMP and of all purines similar to levels in the CD3(–) fraction. The CD3(+) exosomes show significantly lower levels of all factors with almost no adenosine production. (b) 5′‐AMP and purine levels produced by exosomes of the patients divided according to the UICC stage. While the differences were not significant, 5′‐AMP and purine levels in the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) stages I/II group (low stage) were lower than those in the UICC stages III/IV group (high stage). Note the differences in the x‐axis of the graphs. **P < 0·005; ***P < 0·0001.

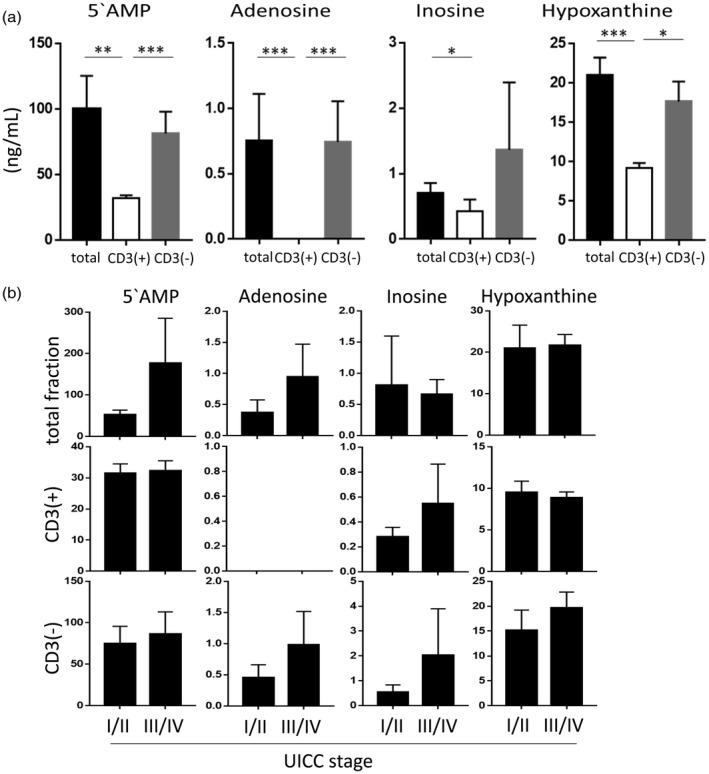

Among CD4+ T cells, Treg co‐incubated with TEX were shown previously to up‐regulate adenosine production [14]. We co‐incubated CD4+CD39+ Treg isolated from normal peripheral blood with the various rapidly fractions of exosomes to determine which of these fractions could up‐regulate Treg activity most effectively (Fig. 4a). In these experiments, total exosomes and CD3(–) TEX‐enriched fractions were shown to up‐regulate production of purines, with the highest enzymatic activity mediated by exosomes from plasma of patients with stages III/IV disease (Fig. 4b). CD3(+) T cell‐derived exosomes showed low levels of enzymatic activity and no correlation with disease activity was noted for adenosine production by Treg co‐incubated with these CD3(–).

Figure 4.

5′‐AMP and purine production by regulatory T cell (Treg) treated with exosomes in the presence of extracellular adenosine 5′‐triphosphate (eATP). The exosome fractions of 10 patients were tested following co‐incubation of Treg with exosomes, as described in Materials and methods. (a) 5′‐AMP and purine levels of Treg co‐incubated with total, CD3(+) or CD3(–) exosomes. Note higher production of 5′‐AMP and of all purines by total exosomes and CD3(–) exosomes compared to CD3(+) exosomes. (b) Treg co‐incubated with total or CD3(–) exosomes from Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) stages I/II (low stage) patients show lower adenosine and inosine levels than exosomes of UICC stages III/IV patients. However, in Treg co‐incubated with CD3(+) exosomes no adenosine was detected, indicating a rapid enzymatic conversion to inosine and hypoxanthine. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·005; ***P < 0·0001.

Adenosine deaminase (ADA) and CD26 levels in exosomes

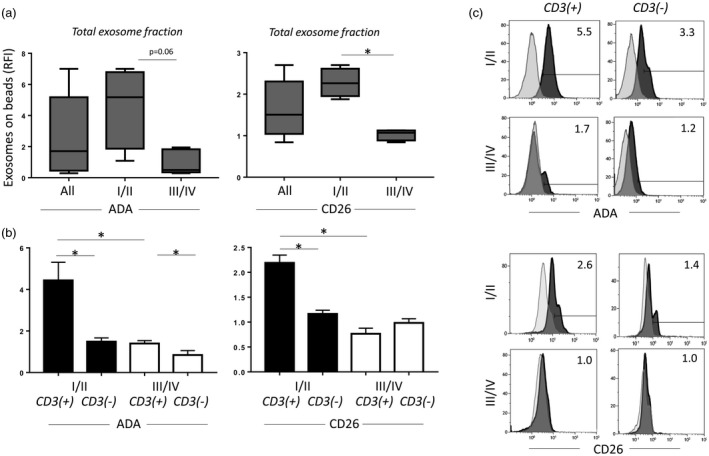

ADA is responsible for the degradation of adenosine, is expressed on T cells and is a key enzyme protecting T cells from suppression by adenosine [7]. CD26 is the binding protein for extracellular ADA, providing an anchor for ADA on the cell surface. These two enzymes are responsible for the reduction of extracellular adenosine levels. We have shown previously that the simultaneous presence of CD26 and ADA was restricted to effector T cells in HNSCC patients [7]. When total exosomes from plasma of HNSCC patients were examined for levels of ADA and CD26, the range of RFI values was very broad (Fig. 5a). However, when HNSCC patients were separated into stages I/II and stages III/IV categories, levels of ADA and CD26 were found to be significantly higher in exosomes from patients with early‐ than late‐stage disease (Fig. 5a). Next, we determined the levels of these enzymes in CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosome fractions of the patients with early versus late disease. As shown in Fig. 5b,c, only exosomes in the CD3(+) exosome fraction in patients with early‐stage disease had significantly elevated levels of ADA and CD26. Exosomes in CD3(–) fractions from stages I/II patients and CD3(+) or CD3(–) exosomes from late‐stage disease patients had equally low levels of the two enzymes. The data show that CD3(+) exosomes produced by T cells in patients with the early‐stage HNSCC carry significantly more ADA and CD26 than CD3(+) exosomes from patients with advanced HNSCC.

Figure 5.

Adenosine deaminase (ADA) and CD26 levels on exosomes. (a) ADA and CD26 levels are higher in total exosomes of patients in the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) low‐stage group, compared to those in the UICC high‐stage group (P = 0·06, P = 0·03, respectively). (b) Dividing the total exosomes into CD3(+) and CD3(–) fractions shows that ADA and CD26 are significantly higher in the CD3(+) fraction of exosomes in patients with low‐stage head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). (c) Representative histograms for (a) and (b) showing the flow cytometry‐based distribution of ADA or CD26 on CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes. *P< 0·05.

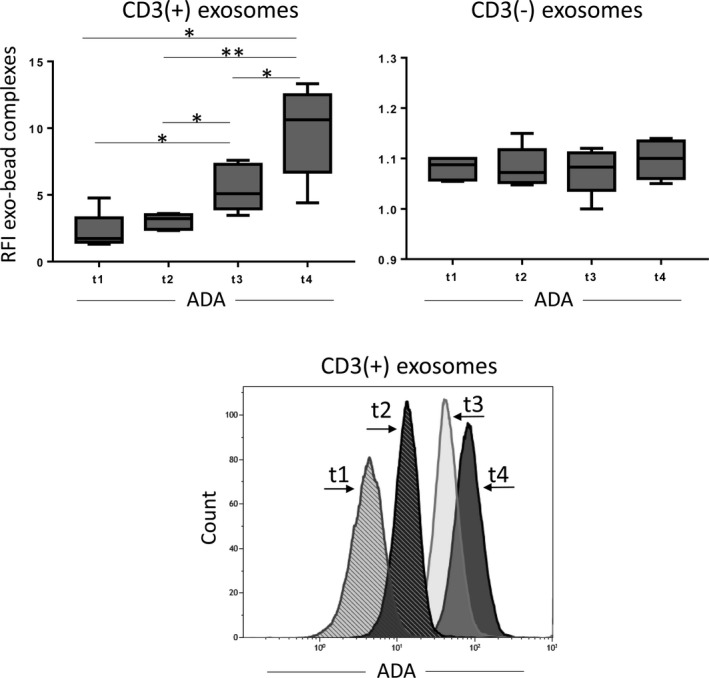

ADA in exosomes of HNSCC patients treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT)

As PDT is known to stimulate anti‐tumour immunity in HNSCC patients, we investigated the ADA levels in the CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes obtained from plasma of the patients before and after PDT (n = 5, at four different time‐points for each patient). These palliative patients were heavily pretreated prior to PDT. The CD3(+) or CD3(–) exosomes obtained from their plasma had little ADA activity at baseline (Fig. 6). However, after PDT, significant increases in ADA levels beginning at day 7 were observed in CD3(+) exosomes. In contrast, ADA levels remained unchanged in CD3(–) exosomes (Fig. 6). The data indicate that PDT is associated with the recovery of T cell functions, which is reflected in the levels of ADA in CD3(+) exosomes derived from these T cells.

Figure 6.

Adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels on CD3(+) and CD3(–) exosomes from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT). Exosomes were isolated from plasma samples at different time‐points before (t1) and after (t2–t4) PDT. ADA levels in the CD3(+) exosomes show a continuous increase from low levels at t1 to high levels at t4. ADA levels in the CD3(–) exosomes remain low before and after therapy. Representative histograms show relative ADA levels on CD3(+) exosomes measured by on‐bead flow cytometry at different time‐points. *P < 0·05 **P = 0·008.

Discussion

The immune system plays a key role in the tumorigenesis of HNSCC. The emerging malignant cells and established tumours are able to evade immune surveillance using a variety of mechanisms that have been identified and described previously [6, 25]. Adenosine is a soluble factor involved in HNSCC escape from the host immune system. Adenosine is a product of ATP and ADP hydrolysis catalyzed by the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase‐1 (CD39). The terminal and rate‐limiting break‐down of AMP to adenosine is catalyzed by ecto‐5′‐nucleotidase (CD73). The immunosuppressive effects of ADO are mediated by the A2AR on effector T cells [26, 27]. In fact, more than a decade ago, Sitkovsky et al. [28] reported that A2AR protects tumours from activated T cells by inhibiting their anti‐tumour functions. While ectonucleotidases are expressed on various cell types, tumour cells [29], as well as Treg, express high levels of CD39 and CD73 and are strong adenosine producers [18, 30]. Additionally, these cells lack expression of CD26, the protein that serves as a cell‐anchor for adenosine deaminase (ADA) in the cell membrane. ADA is an enzyme responsible for conversion of ADO in inosine. We have shown previously that ADA activity and CD26 levels in effector T cells (Teff) are reduced significantly in cancer patients compared to normal controls (NC), implying that the conversion of immunosuppressive adenosine to inosine is reduced in cancer [7]. ADA activity is necessary for sustaining Teff functions, including T cell proliferation and cytokine production [31]. The lack of ADA results in the accumulation of adenosine in the TME, leading to angiogenesis and tumour progression. In this context, adenosine emerges as the major mechanism of tumour escape, while ADA activity of T cells can be viewed as an indicator of immune competence in patients with HNSCC [32, 33].

Plasma‐derived exosomes are heterogeneous mixtures of vesicles derived from many different cells. By separating exosomes into subpopulations, it might be possible to discern the cellular source of exosomes. Using immunoaffinity‐based capture, we have separated CD3(+) from CD3(–) exosomes successfully and showed that the former are produced by T cells while the latter are derived largely, but not entirely, from CD44v3+ tumour cells. These exosomes are enriched in TEX and they produce adenosine spontaneously in the presence of ATP and induce adenosine production in Treg. This CD3(–) exosome fraction is enriched significantly in HNSCC patients with advanced stages III/IV disease relative to their low levels/activity in patients with stages I/II disease. CD3(–) exosomes, like their parental tumour cells, produce and reprogram Treg cells to produce large quantities of suppressive adenosine. Phenotypically (CD44v3+) and functionally, these exosomes reflect the properties of tumour cells. On the host side of the equation, are T cell‐derived CD3(+) exosomes which, in patients with stages I/II HNSCC, carry significantly higher levels of ADA/CD26 than CD3(+) exosomes of HNSCC patients with late‐stage disease. This indicates clearly that these exosomes mimic the characteristics of T cells which function relatively normally early in disease but down‐regulate expression of ADA/CD26 as the disease progresses. The recovery of ADA levels in CD3(+) exosomes of PDT‐treated HNSCC patients who responded to this therapy [9] shows that these exosomes inform us about the state of immune recovery in the patients. Similarly, low levels of ADA on CD3(+) exosomes in HNSCC patients with stages III/IV disease relative to patients with stages I/II disease indicate that the former are immunosuppressed more strongly.

Plasma‐derived exosomes separated into the two fractions by the presence of CD3 on their membranes serve as markers of immune suppression (i.e. adenosine production) mediated by the CD3(–) fraction and also as CD3(+) markers of T cell competence in patients with HNSCC. Ours is the first report demonstrating that exosomes in plasma of cancer patients have a potential to serve as biomarkers of tumour activities and also as biomarkers of immune competence/suppression.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

M.‐N. T. performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. T. K. H. read and edited the manuscript. E. K. J. interpreted results and performed mass spectrometry. T. L. W. designed the study, interpreted results and edited the manuscript. This work has been supported in part by NIH grants RO‐1 CA168628 and R21‐CA204644 to T. L. W., by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to M. N. T. (research fellowship no. TH 2172/1‐1) and by DK079307, DK091190 and HL109002 to E. K. J.

References

- 1. Whiteside TL. Head and neck carcinoma immunotherapy: facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24:6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Duray A, Demoulin S, Hubert P, Delvenne P, Saussez S. Immune suppression in head and neck cancers: a review. Clin Dev Immunol 2010; 2010:701657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferris RL. Immunology and immunotherapy of head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:3293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144:646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ferris RL, Whiteside TL, Ferrone S. Immune escape associated with functional defects in antigen‐processing machinery in head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12:3890–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moy JD, Moskovitz JM, Ferris RL. Biological mechanisms of immune escape and implications for immunotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2017; 76:152–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mandapathil M, Szczepanski M, Harasymczuk M et al CD26 expression and adenosine deaminase activity in regulatory T cells (Treg) and CD4(+) T effector cells in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology 2012; 1:659–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mandapathil M, Hilldorfer B, Szczepanski MJ et al Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4±CD25highFOXP3± regulatory T cells. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:7176–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Theodoraki MN, Lorenz K, Lotfi R et al Influence of photodynamic therapy on peripheral immune cell populations and cytokine concentrations in head and neck cancer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2017; 19:194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wulff S, Pries R, Borngen K, Trenkle T, Wollenberg B. Decreased levels of circulating regulatory NK cells in patients with head and neck cancer throughout all tumor stages. Anticancer Res 2009; 29:3053–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pretscher D, Distel LV, Grabenbauer GG, Wittlinger M, Buettner M, Niedobitek G. Distribution of immune cells in head and neck cancer: CD8± T‐cells and CD20± B‐cells in metastatic lymph nodes are associated with favourable outcome in patients with oro‐ and hypopharyngeal carcinoma. BMC Cancer.2009; 9:292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumai T, Oikawa K, Aoki N et al Tumor‐derived TGF‐beta and prostaglandin E2 attenuate anti‐tumor immune responses in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with EGFR inhibitor. J Transl Med 2014; 12:265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sitkovsky MV, Hatfield S, Abbott R, Belikoff B, Lukashev D, Ohta A. Hostile, hypoxia‐A2‐adenosinergic tumor biology as the next barrier to overcome for tumor immunologists. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2:598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ludwig S, Floros T, Theodoraki MN et al Suppression of lymphocyte functions by plasma exosomes correlates with disease activity in patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23:4843–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Theodoraki MN, Yerneni SS, Hoffmann TK, Gooding WE, Whiteside TL. Clinical significance of PD‐L1(+) exosomes in plasma of head and neck cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24:896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cocucci E, Meldolesi J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol 2015; 25:364–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 2013; 200:373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schuler PJ, Saze Z, Hong CS et al Human CD4± CD39± regulatory T cells produce adenosine upon co‐expression of surface CD73 or contact with CD73± exosomes or CD73± cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2014; 177:531–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Theodoraki MN, Hoffmann TK, Whiteside TL. Separation of plasma‐derived exosomes into CD3((+)) and CD3((–)) fractions allows for association of immune cell and tumour cell markers with disease activity in HNSCC patients. Clin Exp Immunol 2018. doi: 10.1111/cei.13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hong CS, Funk S, Muller L, Boyiadzis M, Whiteside TL. Isolation of biologically active and morphologically intact exosomes from plasma of patients with cancer. J Extracell Vesicles 2016; 5:29289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morales‐Kastresana A, Jones JC. Flow cytometric analysis of extracellular vesicles. Methods Mol Biol 2017; 1545:215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schuler PJ, Harasymczuk M, Schilling B, Lang S, Whiteside TL. Separation of human CD4±CD39± T cells by magnetic beads reveals two phenotypically and functionally different subsets. J Immunol Methods 2011; 369:59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Franzmann EJ, Weed DT, Civantos FJ, Goodwin WJ, Bourguignon LY. A novel CD44 v3 isoform is involved in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001; 124:426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reategui EP, de Mayolo AA, Das PM et al Characterization of CD44v3‐containing isoforms in head and neck cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2006; 5:1163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mandal R, Şenbabaoğlu Y, Desrichard A et al The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight 2016; 1:e89829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raskovalova T, Huang X, Sitkovsky M, Zacharia LC, Jackson EK, Gorelik E. Gs protein‐coupled adenosine receptor signaling and lytic function of activated NK cells. J Immunol 2005; 175:4383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohta A, Gorelik E, Prasad SJ et al A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:13132–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sitkovsky MV, Kjaergaard J, Lukashev D, Ohta A. Hypoxia‐adenosinergic immunosuppression: tumor protection by T regulatory cells and cancerous tissue hypoxia. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:5947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Antonioli L, Pacher P, Vizi ES, Hasko G. CD39 and CD73 in immunity and inflammation. Trends Mol Med 2013; 19:355–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Montalban Del Barrio I, Penski C, Schlahsa L et al Adenosine‐generating ovarian cancer cells attract myeloid cells which differentiate into adenosine‐generating tumor associated macrophages ‐ a self‐amplifying, CD39‐ and CD73‐dependent mechanism for tumor immune escape. J Immunother Cancer 2016; 4:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Climent N, Martinez‐Navio JM, Gil C et al Adenosine deaminase enhances T‐cell response elicited by dendritic cells loaded with inactivated HIV. Immunol Cell Biol 2009; 87:634–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Komi Y, Ohno O, Suzuki Y et al Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by targeting endothelial surface ATP synthase with sangivamycin. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2007; 37:867–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoskin DW, Mader JS, Furlong SJ, Conrad DM, Blay J. Inhibition of T cell and natural killer cell function by adenosine and its contribution to immune evasion by tumor cells. Int J Oncol 2008; 32:527–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]