Abstract

Divers suspected of suffering decompression illness (DCI) in locations remote from a recompression chamber are sometimes treated with in-water recompression (IWR). There are no data that establish the benefits of IWR compared to conventional first aid with surface oxygen and transport to the nearest chamber. However, the theoretical benefit of IWR is that it can be initiated with a very short delay to recompression after onset of manifestations of DCI. Retrospective analyses of the effect on outcome of increasing delay generally do not capture this very short delay achievable with IWR. However, in military training and experimental diving, delay to recompression is typically less than two hours and more than 90% of cases have complete resolution of manifestations during the first treatment, often within minutes of recompression. A major risk of IWR is that of an oxygen convulsion resulting in drowning. As a result, typical IWR oxygen-breathing protocols use shallower maximum depths (9 metres' sea water (msw), 191 kPa) and are shorter (1–3 hours) than standard recompression protocols for the initial treatment of DCI (e.g., US Navy Treatment Tables 5 and 6). There has been no experimentation with initial treatment of DCI at pressures less than 60 feet’ sea water (fsw; 18 msw; 286 kPa*) a since the original development of these treatment tables, when no differences in outcomes were seen between maximum pressures of 33 fsw (203 kPa; 10 msw) and 60 fsw or deeper. These data and case series suggest that recompression treatment comprising pressures and durations similar to IWR protocols can be effective. The risk of IWR is not justified for treatment of mild symptoms likely to resolve spontaneously or for divers so functionally compromised that they would not be safe in the water. However, IWR conducted by properly trained and equipped divers may be justified for manifestations that are life or limb threatening where timely recompression is unavailable.

Keywords: Decompression sickness, Decompression illness, First aid, Treatment, Oxygen, Remote locations, Technical diving

Introduction

Recompression and hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) breathing is the definitive treatment for decompression sickness (DCS) and arterial gas embolism (collectively referred to as decompression illness (DCI)). Ideally, recompression of a diver should take place in the safety of a recompression chamber, but it is also possible to recompress a diver by returning them to depth in the water. The primary motivation for in-water recompression (IWR) is to rapidly treat DCI when a recompression chamber is not readily available. However, during IWR it is not possible to provide other medical care, the patient is exposed to environmental stresses, and a convulsion due to central nervous system oxygen toxicity (CNS−OT) can result in drowning. As a result, IWR is typically conducted at lower pressures, concomitantly lower inspired partial pressures of oxygen (PO2), and for shorter durations than prescribed by recompression tables used in recompression chambers.

IWR has always been controversial; primarily because it is difficult to evaluate its potential benefits versus its recognized risks. Consequently, although IWR has been reviewed many times with input from the diving medicine community, prominent publications providing guidelines on treatment of DCI generally avoid the subject,[ 1 , 2] or are discouraging.[ 3] Some publications provide guidelines for IWR, generally as a last resort if there is no prospect of reaching a recompression chamber within a reasonable time frame.[ 4 , 5]

∗ Footnote:

Consistent with the origin of much of the subject matter reviewed, this paper uses the US Navy convention that 33 fsw = 1 atm (101.3 kPa) (US Navy Diving Manual, Revision 7. Washington (DC): Naval Sea Systems Command; 2016. Chapter 2, Underwater Physics; paragraph 2-9.1.). Using this convention, the conversions for fsw to kPa are: 30 fsw = 193kPa; 33 fsw = 203 kPa; and 60 fsw = 286 kPa. Equivalent depths in msw are expressed to the nearest whole number. Where msw are the original unit, this paper uses the convention that 10 msw = 1 bar (100 kPa) (BRd 2806(2) UK Military Diving Manual. Fareham: Fleet Publications and Graphics Organisation. April 2014 Edition. Air Diving. Chapter 6, Decompression; paragraph 0603.g.). Using this convention, the conversions for msw to kPa are: 9 msw = 191 kPa; 10 msw = 201 kPa; and 18 msw = 281 kPa.

There are compelling reasons to revisit this issue. IWR continues to be promoted by some of the world's prominent diving medical experts for use by diving fisherman populations in locations remote from recompression chamber facilities.[ 5 - 7] Recreational diving is increasingly taking place in such locations. Moreover, with the increase in so-called "technical diving" there are more divers with the requisite equipment and skill mix that might be considered appropriate for conduct of IWR.[ 8] There is no documentation of how frequently technical divers use IWR, but one technical diving training organization has begun conducting training in IWR methods.[ 9] Divers suffering neurological DCI are often left with residual neurological problems despite evacuation for recompression.[ 3 , 10] There is a widely held belief that early recompression may be associated with better outcomes in such cases and IWR offers an obvious opportunity for very early recompression. It is thus possible to argue for consideration of IWR by appropriately trained divers for serious DCI cases in locations without ready access to a recompression chamber.

This paper begins with a brief review of previous experience with IWR, and a perspective on the relatively negative stance of the medical community over the years. We then address the pivotal issue of risk versus benefit. Most relevant studies do not address the potential benefit of the extremely early recompressions that can be achieved either with a recompression chamber on site or by using IWR methods. Therefore, we will focus on the sparse existing data pertaining to this issue and introduce new data not previously evaluated for this purpose. We will review the evidence that lower pressure and shorter recompressions can be effective in treating DCI when implemented early. The risks of IWR will be enumerated along with potential mitigations. Finally, we briefly discuss diver selection for IWR and potential approaches to its implementation.

Reports of in-water recompression

The fundamental problem bedevilling an objective evaluation of the utility of IWR (and, therefore, its wider acceptance) is a lack of data on cases and outcomes (both good and bad) where the clinical data can be considered reliable. There are a number of reports of apparently good results from systematic use of IWR by particular groups, but in most cases it is unclear how the data were gathered and to what extent there was any objective evaluation of the divers before and after IWR.

In a survey of their diving practices, Hawaiian diving fishermen self-reported 527 IWR events where air was used as the breathing gas, and in 78% of cases there was complete resolution of symptoms.[ 11] While this seems very positive, there was no independent verification of the severity of these cases, or of the alleged recoveries. Moreover, the apparent success of IWR in this survey approximates the rate for spontaneous recovery from cases of DCI reported in historical data before recompression became considered a standard of care.[ 12] Thus, while supportive, these data are of limited use in evaluating the efficacy of IWR.

Edmonds described a 1988–1991 study of log books maintained by pearl divers in Australia describing more than 11,000 dives.[ 13] The sample represented approximately 10% of divers working in the pearl diving industry operating out of Broome and Darwin over the period. There were 56 cases of DCI identified, all of which were treated by IWR on oxygen (O2), typically at 9 metres' sea water (msw; 191 kPa), and instituted within 30 minutes (min) in most cases. Outcomes were apparently excellent with only one of the 56 requiring evacuation for further recompression in a chamber. It was notable that no cases of oxygen seizure were reported during any of these recompressions. Frequent use of IWR in the Australian pearl diving industry was corroborated by Wong who observed that in the Broome arm of the industry approximately 30–40 cases of mild DCI were treated every year (presumably in the years leading up to his 1996 publication) using IWR with oxygen.[ 14] However, as with the Hawaiian data, in neither of the Australian series was the severity of DCI or the recovery documented prospectively by competent observers.

Other populations of indigenous diving fishermen have been noted to "routinely" employ in-water recompression for DCI. In an observational study of their diving patterns it was reported that sponge divers of the Galapagos described frequent success with IWR on air.[ 15] However, the investigators only personally witnessed one case treated with IWR, which did not succeed in relieving the symptoms. One attempt has been made to measure outcomes in a small sample of the "sea gypsies" of Thailand who typically employ early IWR (within 60 min of symptom onset) using air at depths between 4 and 30 m and for durations between 5 and 120 min.[ 16] In 11 cases (of uncertain severity), seven had complete recovery, two had improvement at depth but return of symptoms back at the surface and two did not appear to benefit at all.

In 1997, a discussion paper described 16 moderately well documented cases of DCI treated with IWR (Table 1).[ 17] These cases have qualitative value in illustrating the spectrum of possible outcomes when the technique is employed. Importantly, unlike the poorly documented series involving sea harvesting divers, a large proportion of the cases were known to involve severe symptoms which would not usually be expected to resolve spontaneously. It seems clear from Table 1 that IWR using either air or O2 appears to have positively modified the natural history of some severe cases. It is also germane that divers involved in two of these incidents (cases 2 and 13–15), but who chose not to be recompressed in-water, died during evacuation, whereas those who recompressed in-water survived. Equally, there were cases (both using recompression on air) where divers either worsened (case 11) or perished (cases 3 and 4) during IWR. Although the numbers are small and firm inferences are not justified, all the cases treated with O2 could be interpreted as having reaped some benefit (and no obvious harm) whereas all the poor outcomes (relapses, treatment failures, or fatalities) occurred when air alone was used.

Table 1. Summary of data derived from 16 cases treated with IWR;17 "up" implies a staged decompression regimen from the reported maximum depth; "Severe" implies potentially disabling neurological manifestations; "Mild" implies pain and/or subjective neurological manifestations; some latencies, durations and depth are approximated from the history provided .

| Delay | Depth | Duration | ||||

| Case | Severity | (min) | (m) | (min) | Gas | Outcome and notes |

| 1 | Severe | < 15 | 18 up | 50 | Air | Initial relief with recurrence and evacuation for chamber treatment; incomplete recovery |

| 2 | Severe | <30 | 12 | < 120 | Air | Complete recovery; buddy who elected not to have IWR died |

| 3, 4 | ? | <30 | ? | N/A | Air | Both divers died, failing to return to the surface |

| 5 | Severe | 0 | 24 up | ? (> 60) | Air | Complete recovery |

| 6 | Severe | < 5 | 24 up | ? | Air | Complete recovery |

| 7 | Mild | < 30 | 12 | ? | Air | Complete recovery |

| 8 | No symptoms | < 5 | 6 | 60 | 100% O2 | Substantial omitted decompression, no symptoms developed |

| 9 | Severe | 38 hrs | 8 | ∼200 | 100% O2 | Complete recovery |

| 10 | Severe | 180 | 9 | > 60 | 100% O2 | Complete recovery |

| 11 | Mild | ? | ? | ? | Air | Symptoms worsened and paralysis ensued despite chamber treatment |

| 12 | Severe | < 30 | 15 up | ? | Air | Complete recovery |

| 13, 14, 15 | Severe | ? | 12 | ? | 100% O2 | Incomplete recovery in all three after chamber treatment; a fourth diver who elected not to have IWR died |

| 16 | Mild | < 90 | 30 up | 90 | 50% O2 | Complete recovery |

Most recently, a programme designed to educate Vietnamese fishermen divers about safe diving practices and methods for IWR was described and 24 cases of DCI treated with IWR were reported.[ 7] Ten cases with pain-only symptoms were recompressed by IWR using air, and all had complete relief. There were 10 cases of neurological DCI of which four were treated by IWR using O2 (9 msw depth for 60 min), all of whom recovered completely. In contrast, only two of the six cases undergoing IWR using air recovered immediately. Thus, like the 1997 series, this account also suggests that IWR using oxygen is more effective than using air.[ 7 , 17]

Principal controversies

There has been a long-standing reluctance by peak bodies in diving medicine to recognize IWR as a legitimate option for managing DCI. This reticence is explained by the risks of IWR, and the concomitant lack of medically supervised demonstration of its efficacy. There are a number of potential risks in using IWR (see below) but the use of O2 as the treatment gas is a major concern since a convulsion due to CNS−OT whilst immersed at depth carries a significant risk of drowning. This concern is greatest if ill-equipped divers with inadequate training and experience attempt to apply the technique. However, with some diving groups being trained to use O2 underwater it may be time to revise the medical community's attitude to use of IWR by those divers who are demonstrably better trained and equipped for its successful application.

Notwithstanding the case series above suggesting that IWR can be effective, there are no convincing data that it offers any advantage over the safer first-aid alternative of surface O2. Specifically, what is missing from the above appraisal of the evidence for efficacy is an experimental comparison of outcomes achieved if a diver is simply treated with surface O2 and evacuated to the nearest suitable hyperbaric chamber (even if this takes some time) versus earlier recompression to modest pressures using IWR. Such experiments are extremely unlikely to ever be undertaken. However, it is possible to make inferences on the efficacy of IWR based on the efficacy of early recompression to modest pressures (key features of IWR) achieved in other contexts. This is discussed in the following two sections.

Efficacy of treatment following short delay to recompression

Since it is theoretically possible to (eventually) evacuate anyone from anywhere to a recompression chamber, the key question is whether there is a threshold delay between onset of symptoms and signs of DCI and recompression (delay to recompression) beyond which prognosis for recovery worsens. There are no prospective studies on the effect of delay to recompression treatment for DCI. A number of retrospective studies report the effect of delay to treatment.[ 3 , 10 , 18 , 19] A chapter in the Management of mild or marginal decompression illness in remote locations Workshop proceedings articulated some of the challenges of conducting such studies, and reasons for variability in the effect of delay to treatment between studies.[ 19] These included difficulties associated with retrospective review, interaction of symptom severity and delay to treatment and the use of an imperfect outcome measure (full recovery versus presence of residual symptoms and signs).[ 19]

Analysis of Divers Alert Network data shows a small increase in the presence of residual symptoms after all recompression treatments with increasing delay to recompression for mild DCI. However, as would be expected with mild symptoms, this difference disappears at long-term follow-up.[ 19 , 20] These case series analyses were conducted in the context of retrieval of recreational divers, often from remote locations, and the median delays to treatment ranged from 16 to 29 h in different sets of data analyzed.[ 3 , 20]

Of greater relevance is the effect of delay to recompression in the presence of serious neurological symptoms. Analysis of Divers Alert Network data with divers stratified into a group designated "serious neurological" demonstrated a downward inflection (from approximately 60% to approx. 40%) in the proportion of divers making a full recovery after completion of all recompression therapy if the delay to recompression was > 6 h.[ 3] In another series of 279 divers with spinal DCS stratified according to delay to recompression latency (< 3, 3–6, > 6 h), the percentage of patients making a full recovery at one month follow-up in each group was 76%, 82%, and 63% respectively.[ 10] It is notable that delay to recompression was an independent predictor of outcome on univariate analysis, but not in a multivariate logistic model which included qualitative descriptions of symptoms and their progress at presentation.[ 10]

The above data pertain primarily to recreational diving scenarios where even the shorter delays to recompression are measured in hours rather than minutes. Evaluating any advantage of earlier recompression on the basis of such data may therefore underestimate the benefit of very early recompression. Indeed, it is widely believed that very early treatment, such as might occur in commercial or military settings where a recompression chamber is readily available, is likely to result in the best outcomes. Unfortunately, published data, all from the military, are relatively sparse.

In a dataset of military and civilian divers treated for DCS by the US Navy between 1946 and 1961, 885 cases had known delay to recompression.[ 21] Full recovery after all treatments was 98% or greater in all subgroups of two hours or less delay to recompression (< 15, 16–30, 31–60, 61–120 min) and 95% in divers treated within 3–6 h delay to recompression. Full recovery declined substantially for longer delays. It should be noted that these cases were treated with the US Navy Treatment Tables 1–4, before the development of the minimal-pressure O2 breathing US Navy Treatment Tables 5 and 6 (USN TT5 nd USN TT6),[ 22] which have since become the standard of care. In a recently reported smaller case series of 59 military divers with neurological DCI who were treated a median of 35 min (range 2–350 min) after symptom onset, the odds of incomplete recovery at one month follow-up increased with delay to recompression. However, it is not possible to interpret the magnitude of this effect as it is not clear if delay was treated as a continuous variable in the logistic regression.[ 23]

A particularly high success rate for treatment of DCI is reported from US Navy diver training and experimental diving facilities, where, as a result of heightened vigilance among divers, close medical supervision and ready availability of recompression facilities, treatments are usually initiated within two hours of symptom onset. Fifty consecutive cases of DCS occurring at the Naval School of Diving and Salvage from 1975 to 1978 were treated with a single USN TT5 or 6 (eight Tables were extended), and 46 of these were recompressed within two hours of symptom onset.[ 24] Forty-nine patients reported complete relief of symptoms shortly after compression to 60 feet' sea water (fsw) (286 kPa, 18 msw) at the start of the treatment. One patient had residual arm soreness after a single recompression that resolved spontaneously over five days. In another series, 292 Type I DCS cases were treated at the Naval Diving and Salvage Training Center and Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) with a single USN TT5 or 6.25 The delay to recompression is not given but is presumably short. Two hundred and eighty patients (96%) had complete relief after a single recompression. In a third series, 166 cases of DCS arising from experimental dives at NEDU and the Naval Medical Research Institute (NMRI) were recompressed from 1980–1989.[ 18] USN TT5 or 6 were used in all but four cases (two Treatment Table 4s, one Treatment Table 7 and one 60 fsw saturation treatment) and there was "little or no delay between symptom occurrence and treatment". One hundred and nineteen cases (72%) resolved during compression or within the first 10 minutes at depth during the first recompression treatment, 161 cases (97%) had complete resolution of DCS at the end of the first recompression treatment and all resolved eventually.

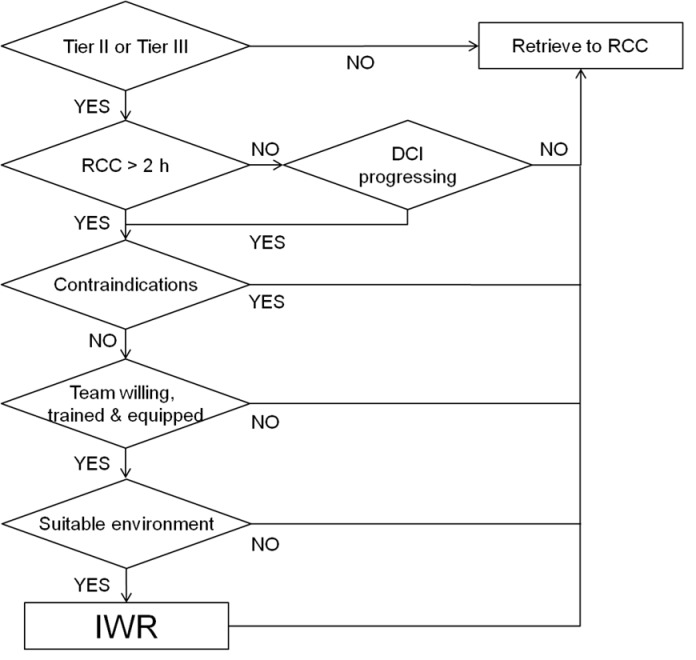

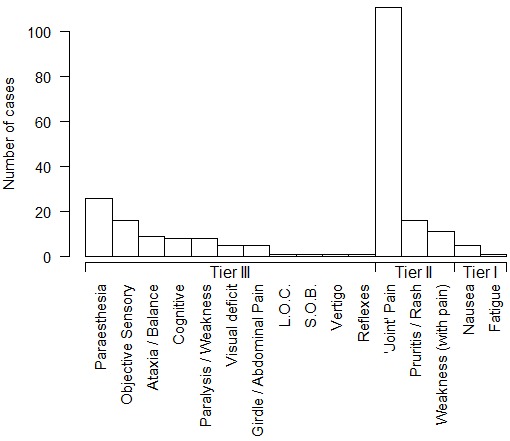

In addition to the above, we have collated reports of 140 cases of DCS arising from experimental dives at NEDU, NMRI, and the Naval Submarine Medical Research Laboratory from 1988 to 2006 in which delay to recompression and details of the clinical course are available.[ 26 , 33] Up to 16 of these cases may overlap with those previously reported.[ 18] Figure 1 shows the frequency of symptoms and signs in these 140 cases arranged into the ‘tiers’ that comprise a published diver selection algorithm for IWR (Table 2).[ 09] Figure 2 shows the delay to onset of symptoms and signs after surfacing. Figure 3 shows the distribution of delays to recompression.

Figure 1.

Symptoms and signs of 140 cases of DCS arising from experimental dives at three US Navy research facilities from 1988 to 2006 (see text for Tier classification); "Paralysis/Weakness" includes motor weakness, whereas "Weakness (with pain)" is weakness associated with a painful joint; "Girdle/Abdominal Pain" includes bilateral hip pain; "L.O.C. − loss of consciousness; "S.O.B." − shortness of breath. "Joint pain" refers to classic musculoskeletal pain in the vicinity of a joint; "Nausea" is without vertigo and vomiting

Table 2. Symptom severity 'tiers' for triage of DCI for IWR adapted from the International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers in-water recompression course for technical divers[ 9] .

| Tier I: Non-specific symptoms that may not be DCI and do not represent a significant threat: Lethargy; Nausea; Headache |

| Tier II: Symptoms and signs likely to be DCI but unlikely to result in permanent injury or death irrespective of treatment: Lymphatic obstruction (subcutaneous swelling); Musculoskeletal pain (excluding symmetrical "girdle pain" presentations); Rash; Paraesthesias (subjective sensory changes such as "tingling") |

| Tier III: Symptoms and signs likely to be DCI and which pose a risk of permanent injury or death: Changes in consciousness or obvious confusion; Difficulty with speech' Visual changes; Walking or balance disturbance; Sensory loss (such as numbness) that is obvious to the diver or examiner; Weakness or paralysis of limbs that is obvious to the diver; or examiner; Bladder dysfunction (inability to pass water); Sphincter (bowel) dysfunction; Loss of coordination or control in the limbs; Shortness of Breath; Girdle pain syndromes (such as both hips, abdomen, or back) |

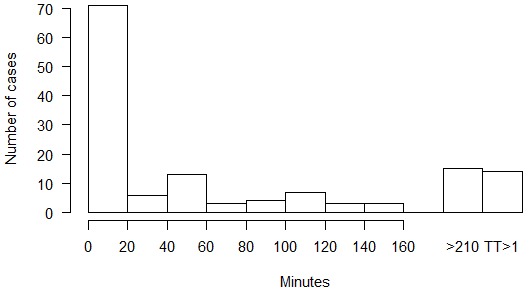

Figure 2.

Delay to onset of symptoms and signs after surfacing from diving in 140 cases of DCS arising from experimental dives at three US Navy research facilities from 1988 to 2006; five cases with symptom onset before surfacing are included in the first bar

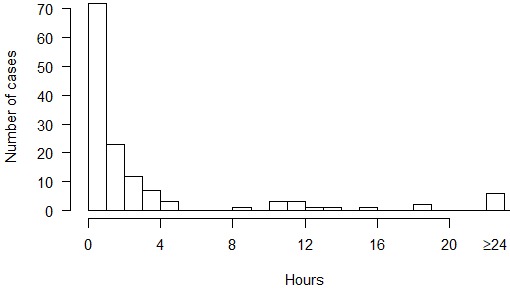

Figure 3.

Delay to recompression after onset of symptoms and signs in 140 cases of DCS arising from experimental dives at three US Navy research facilities from 1988 to 2006

The median delay to recompression was one hour. The majority of cases (87%) were treated within five hours of symptom onset. The initial recompression treatment was USN TT6 (with or without extensions) in 122 cases, USN TT5 (with or without extensions) in 16 cases, US Navy Treatment Table 7 and Comex 30 in one case each. Seventy-one cases (51%) resolved during compression or during the first 20-minute oxygen breathing period at 60 fsw, and 126 cases (90%) had complete resolution of DCS after the first recompression treatment. The distribution of times to resolution of symptoms or signs during recompression is shown in Figure 4. In 14 cases, complete resolution of DCS required two to five recompression treatments (number of treatments/number of cases: 2/6; 3/3; 4/2; 5/1; 9/1; 14/1). There was nothing notable about the clinical presentation in the cases requiring multiple recompression treatments; the median delay to recompression was 0.44 h (range 0–94 h) and although nine of the 14 cases were severe DCS, twice as many severe DCS cases resolved with a single treatment.

Figure 4.

Time to resolution of signs and symptoms during recompression in 140 cases of DCS arising from experimental dives at three US Navy research facilities from 1988 to 2006; times are generally from the beginning of oxygen breathing at treatment depth, but the first bar includes resolution during descent; the last bar indicates the number of cases that required more than one recompression treatment to achieve complete resolution of symptoms

There is insufficient variation in the times to treatment or outcomes in these US Navy training and experimental dives to identify an effect of time to treatment, but the efficacy of a single recompression in these data are in contrast to reported experience among mainly civilian divers.[ 10 , 34] For instance in a large contemporaneous case series of 520 mainly recreational divers, the median time from surfacing to treatment at a civilian recompression facility was two days and requirement for multiple recompression treatments was common (mean number of re-treatments = 1).[ 34] In this same case series, excluding those lost to follow-up, 438 (88%) divers had complete recovery after all treatments and 61 (12%) had incomplete recovery, a significantly lower proportion of complete recovery than in the 140 military experimental divers (P < 0.0001, two-sided Fisher's exact test). Collectively, the military data signal that delay to recompression of two hours or less is associated with a good prognosis for full recovery.

Shallow and short treatments

To manage the risk associated with IWR, recommended protocols typically involve recompression to a maximum depth of 30 fsw (193 kPa, 9 msw) breathing O2 for 3 h or less (this is further discussed in the 'Risks and mitigation' and 'In-water recompression protocols' sections below). Figure 4 indicates that 88% of cases in our new series had complete resolution of signs and symptoms within 3 h after a short delay to recompression. This is an encouraging statistic for IWR, but since Figure 4 describes outcomes from principally USN TT5 and 6, it is possible that symptoms and signs may not resolve as quickly with HBO at shallower depths and may recur during decompression from shorter treatments.

Since the introduction of the USN TT5 and 6,[ 22] treatment tables which prescribe O2 breathing at 60 fsw have become the standard of care, and there has been essentially no experimentation with treatment tables beginning at shallower depths or for shorter durations for the initial treatment of DCI. However, it is not widely appreciated that the development of these two tables included testing of treatment at both 33 fsw (203 kPa, 10 msw) and 60 fsw for relatively short durations.[ 22]

In these test programmes the "provisional" protocol was to compress divers breathing O2 to 33 fsw and, if complete relief of symptoms occurred within 10 min, O2 breathing was continued at this depth for 30 min after relief of symptoms and during decompression to the surface at 1 fsw·min⁻¹. If relief was not complete within 10 min at 33 fsw, divers were compressed to 60 fsw. If complete relief of symptoms occurred within 10 min at 60 fsw, O2 breathing was similarly continued at this depth for 30 min and during 1 fsw·min⁻¹ decompression to the surface. The test report tabulates 31 shallow recompression treatments that generally followed these rules:[ 22] 27 at 33 fsw, three at 30 fsw and one at 20 fsw. Seven treatments had longer time at maximum depth than specified above. Excluding one 26-h treatment, the total treatment times ranged from 35 to 180 min (mean 70 min). DCI signs and symptoms treated at 33 fsw or shallower (number of cases) included pain (26), special senses (6), rash (5), sensory (3), chokes (3), syncope (3), motor weakness/paralysis (3), loss of consciousness (1) and nausea and vomiting (1). Being largely treatments for experimental dives, the delay to recompression was relatively short, with a median of 37 min (range 0–270 min). It is perhaps pertinent that many of the inciting dives were non-trivial, including trimix bounce decompression dives to 200–400 fsw (61–122 msw), direct (no-stop) ascents from shallow 12-h sub-saturation exposures, and repetitive air decompression dives to a maximum of 255 fsw (78 msw). Twenty five of these 31 shallow treatments resulted in complete relief. Two treatments resulted in substantial relief; in one case the residuals are reported to have resolved spontaneously over three days. Four treatments were followed by recurrence of symptoms; in three cases complete relief was reported following a second treatment.

The report also tabulates 56 recompression treatments deeper than 33 fsw, mostly at 60 fsw.[ 22] There are three treatments which included compression to 165 fsw (50 msw) for relief of symptoms, two of these were followed by O2 breathing at 60 fsw and one by O2 breathing at 30 fsw. There are two treatments with an initial compression to 165 fsw that appear to be US Navy Treatment Table 6A (USN TT6A).

Collectively, these 56 deeper recompressions resulted in complete resolution of symptoms and signs in 53 cases. This just fails to reach statistical significance in comparison to outcomes of the shallow treatments (P = 0.0653, two-sided Fisher's exact test). Fewer than half of the 56 deep treatments represent failure to obtain complete relief within 10 min at 33 fsw in accord with the provisional protocol. Seven of the 56 deeper treatments had relief of symptoms shallower than 33 fsw but nonetheless continued to 60 fsw. The initial evaluation for relief of symptoms at 33 fsw was discontinued at an unspecified point in the test programme. Twenty-three of these treatments without the initial evaluation at 33 fsw can be identified with reasonable certainty: 13 treatments appear to follow the provisional 60 fsw treatment time, eight treatments appear to be the 'final format', i.e., USN TT6, and two appear to be the aforementioned USN TT6A.

Typical IWR protocols are of relatively short duration, comparable to the USN TT5 which lasts 135 min if not extended. As has been described earlier, USN TT5 is highly effective in the treatment of mild DCI when delay to recompression is short.[ 25] However, USN TT5 has a reported high rate of treatment failures for neurological DCI, albeit with significant delays to treatment in some cases.[ 35] Others report better success with short treatment tables for all manifestations of DCI, and with substantial delay to recompression (median 48 h): the 150-min, no-air-break Kindwall-Hart monoplace treatment table, which is similar to the progenitor of the USN TT5,[ 22] resulted in full recovery after all treatments in 98% of 110 cases of DCS.[ 36] In addition to providing evidence for the efficacy of relatively shallow recompression in cases recompressed relatively quickly, the US Navy treatment table development data presented here demonstrate the efficacy of the relatively short provisional protocol; the median total duration of their 87 treatments was 105 min, and 64 (74%) of the treatments were shorter than 135 min.[ 22]

Risks and mitigation

The potential benefit of earlier recompression using IWR must be balanced against its risks. These risks and their potential mitigations are relatively well understood and have been discussed extensively elsewhere.[ 9 , 17 , 37]

OXYGEN TOXICITY

A major risk of IWR is CNS−OT. This can manifest as a seizure, often without warning, and such an event underwater carries a significant risk of drowning. Seizure risk is a function of dose (inspired PO2 and duration). The inspired PO2 threshold below which seizures never occur irrespective of duration has not been defined but it is lower than exposures recommended for IWR (typically breathing 100% O2 at 9 msw depth). Thus, while we are not aware of any reports of an oxygen toxicity event during IWR, seizures have certainly occurred in O2 exposures of similar magnitude. In experimental O2 dives (> 95% O2 by rebreather), convulsions have not been observed at 20 or 25 fsw (163 or 178 kPa, 6 or 8 msw), but seven "probable" O2 toxicity symptoms (nausea, dizziness, tingling, numbness, tinnitus, dysphoria) occurred in 148 man-dives to 20 fsw for 120 to 240 min duration while performing mild exercise (equivalent to 1.3 L·min⁻¹ VO2).[ 38] Under otherwise the same experimental conditions, no symptoms of CNS–OT occurred in 22 man-dives to 25 fsw for 240 min.[ 38] In other experiments, six divers developed symptoms of CNS–OT in 63 man-dives to 25 fsw of 120−240 min duration (reviewed in ref[ 39]). Convulsions have been observed during 30 fsw resting and exercising O2 dives; in 92 man-dives of 90−120 min durations, three convulsions occurred at 43, 48, and 82 min, respectively.[ 39 - 41]

The actual risk of an O2 seizure during IWR using O2 cannot be usefully extrapolated from such studies because an individual's risk is so context sensitive. In this setting "context" refers to many factors such as individual susceptibility (which appears to vary widely), exercise (higher risk) versus rest (lower risk), and CO2 retention (higher risk). It is also notable that divers undertaking IWR will have an immediately prior exposure to elevated inspired PO2 which would increase risk. In the case of a technical diver this exposure may be substantial.

Mitigation of the risk of CNS-OT can focus either on preventing such an event, or lessening the risk of complications if one occurs. In relation to prevention, there is an obvious tension between the goal of safely increasing pressure to achieve bubble volume reduction, and the safety of the inspired PO2. Arguably the most effective way of reducing the likelihood of a seizure is to reduce the inspired PO2 into a range where seizures seem rare. While most IWR protocols recommend recompression breathing O2 at 30 fsw (9 msw), for a limited time, a reduced risk of O2 toxicity could be achieved by limiting oxygen breathing to lower pressures. For example, the protocol taught on the International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers IWR course prescribes the vast majority of time to be spent at 25 fsw.[ 9]

Mitigating the risk of a seizure, if it occurs, centres primarily on protecting the airway. This can be achieved (though not guaranteed) through the use of a full-face mask, or a mouthpiece retaining strap.[ 42 , 43] Other key risk management strategies include tethering the diver to a decompression stage throughout the recompression so that they cannot sink in the event of loss of consciousness, and ensuring that the diver is accompanied at all times so they can be rescued immediately to the surface if a seizure occurs. Rescue of a seizing diver is discussed elsewhere.[ 44]

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Divers requiring IWR risk becoming cold or even hypothermic. In technical diving scenarios, they may already have completed long dives in cold water. On the plus side, the use of dry suits is common among these divers, and so is the application of active heating systems in dry suit undergarments. It is beyond the scope of this review to discuss thermal considerations in detail, but this is a factor that must be taken into account in deciding whether to undertake IWR. IWR requires a stable platform that can remain in one place for three hours. Changes in environmental factors like weather, current and light can all potentially cause disruption to an IWR process, and projections of these factors should be taken into account in deciding whether to undertake IWR.

PATIENT DETERIORATION

It is well recognized that divers with DCI can deteriorate clinically despite (and indeed during) recompression. Such deterioration during IWR, particularly in respect of consciousness, could represent a very real threat to safety. This threat can be mitigated by careful selection of patients for IWR (see below and Table 2), and ensuring that a patient is accompanied at all times, so that the procedure can be safely abandoned and the patient assisted to the surface in the event of deterioration. Limiting the depth of recompression and use of equipment that helps to protect the airway, such as a full-face mask or mouthpiece retaining device, are also useful mitigations in this context.

A related question is whether IWR itself can be the cause of a worse DCI outcome. This is an issue sometimes raised in respect of using air for IWR. Although recompression on air will produce an initial compression of bubbles, and possibly a related clinical improvement, bubbles will dissolve more slowly and more inert gas will be taken up into some tissues. Persistent bubbles will re-expand and possible take up more gas during decompression, with a possible recurrence or worsening of symptoms. Such mechanisms may help explain outcomes such as those in cases 1 and 11 in Table 1. This argument along with the corroborating observational evidence of weaker efficacy if IWR is conducted on air[ 7 17] probably constitutes adequate justification for recommending that O2 is always used and air be avoided.

DIVER SELECTION

One of the most vexing challenges of IWR is the selection of DCI-afflicted divers whose condition justifies the risks of IWR and whose clinical state does not contraindicate it. There is no agreed formula for such determinations. The risk of IWR may not be justified for those cases where the natural history of the symptoms is for spontaneous recovery irrespective of whether the diver is recompressed or not. The findings of the UHMS 2004 remote DCI Workshop provide some guidance on how a "mild DCI" presentation that might not justify the risks of IWR could be defined.[ 45] The symptom constellation comprising the mild syndrome was one or more of musculoskeletal pain, rash, subjective sensory change in a non-dermatomal distribution, and constitutional symptoms such as fatigue. The workshop concluded that divers with presentations limited to these symptoms could be adequately managed with surface oxygen and careful observation after discussio with a diving physician. It could therefore be argued that exposing divers with static mild symptoms to the risks of IWR might not be justified. At the other extreme of severity, IWR should not be undertaken if the diver is so compromised that they would not be safe in the water. In between these extremes, there will be many potential presentations, and decisions may not be straightforward. Decisions about which cases to recompress in water are likely to be nuanced and difficult to codify in rules.

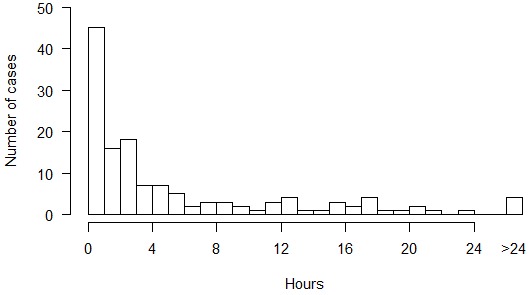

In an attempt to bring some structure to the decision-making process around IWR for divers in the field, (and following a consensus meeting with expert diving medical input) the International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers recently categorized potential DCI symptoms into "tiers" (Table 2). These lists are intended to be sufficiently descriptive as to allow application by divers without medical training, and their application relies on history or gross observation alone, as opposed to a more detailed neurological examination as might be conducted by someone with medical training. The tiers conform approximately to both perceived severity and levels of justification for IWR to provide a guide to the appropriateness of the intervention. Thus, divers with only Tier I symptoms would not justify IWR. That is not to say that the symptoms should be ignored. The diver should be carefully monitored and perhaps discussed with a diving medicine authority, but they would not justify IWR unless the symptoms progressed beyond Tier I. At the opposite end of the spectrum, divers with Tier III symptoms or signs do justify expeditious IWR provided the logistic requirements for IWR are met and there are no contraindications. Divers with Tier II symptoms present the greatest challenge. Where a diver reports Tier II symptoms some hours after surfacing and where those symptoms are not progressive, the risk of IWR is probably not justified. On the other hand, where Tier II symptoms occur early after a dive and appear progressive, prompt IWR could be justified on the basis that it may prevent the development of more serious symptoms.

Contraindications for in-water recompression

There are several signs of DCI which pose a risk of permanent injury, but which are contraindications for IWR and are therefore not included in the Tier III list. Hearing loss and vertigo are both potential symptoms of DCI that can lead to permanent injury. However, when they occur in isolation, that is, with no other symptoms of DCI from any of the other tiers, it is possible that they have been caused by inner ear barotrauma rather than DCI. Inner ear barotrauma is generally considered a contraindication for recompression. Moreover, even when caused by DCI, vertigo is a debilitating symptom which is usually accompanied by nausea and vomiting, and which would make IWR hazardous. Change in consciousness is included in the Tier III group, where it is meant to indicate transient episodes. A diver with a deteriorating level of consciousness or with a persisting reduced level of consciousness should not be recompressed in-water. Other contraindications for IWR include an unwilling or reticent patient, O2 toxicity as part of the course of the preceding events and any physical injury or incapacitation to the point where the diver may not be able to safely return to the water.

In-water recompression protocols

The requirements for conducting IWR have been detailed elsewhere,[ 9 , 17 , 46] and include: a patient willing and capable of undergoing IWR; adequate thermal protection; a means of supplying 100% O2 (or close to it) underwater for the duration of the anticipated protocol; a stable platform for maintaining depth, such as the bottom or a decompression line or stage under a boat; a method for tethering the patient; and a competent experienced buddy to accompany the patient. All divers involved (a minimum of a surface supervisor, dive buddy and patient) must be competent in IWR methods, achieved through specific training in IWR methods or in O2 decompression procedures. A full-face mask or mouthpiece-retaining device is strongly recommended.

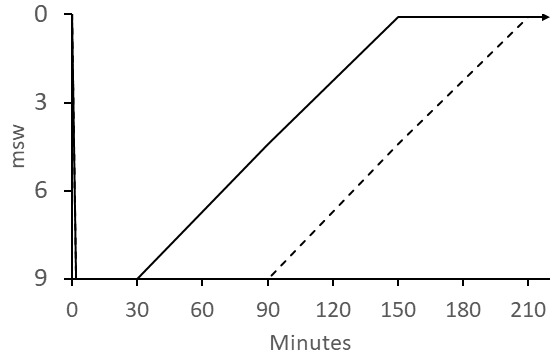

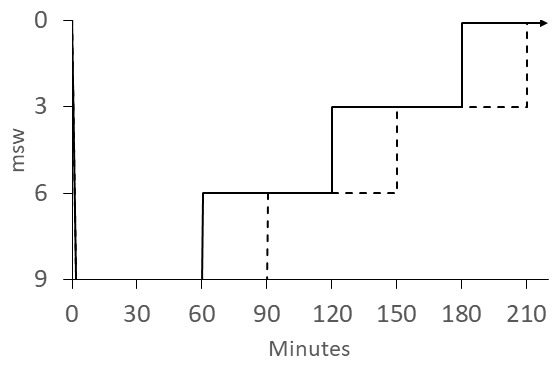

Most published schedules for IWR involve recompression to 30 fsw (9 msw) while breathing pure oxygen. The best known of these is the "Australian" method (Figure 5). The US Navy IWR schedule (Figure 6) is adapted from the Australian method but instead of ascending at 4 min·fsw⁻¹, it prescribes a 120-min decompression with 60-min stops at 20 and 10 fsw (6 and 3 msw).[ 4] It was noted that divers often continued to improve during ascent using the Australian procedure and this was attributed to faster dissolution of bubbles than their Boyle's-law expansion.[ 6] We support the more gradual ascent prescribed in the Australian procedure. The Clipperton procedure (Figure 7) was proposed as a shorter alternative to other procedures to mitigate dehydration and risk of O2 toxicity.[ 7]

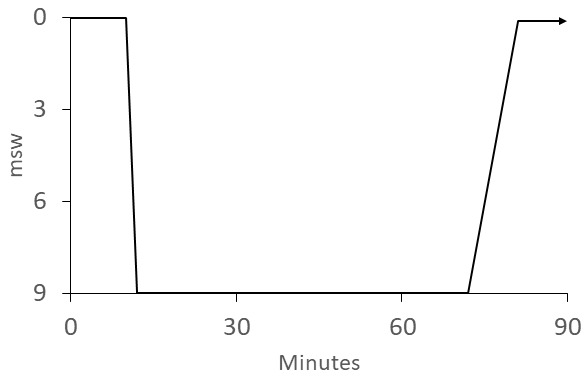

Figure 5.

Australian IWR schedule; the patient breathes oxygen at 9 msw (30 fsw) for 30 min for mild cases, 60 min for serious cases, and for a maximum of 90 min if there is no improvement in symptoms. The patient continues to breathe O2 during the 120-min ascent; the ascent rate was originally specified as 1 fsw (0.3048 msw) every 4 min; dashed line shows ascent from maximum 90 min bottom time; O2 breathing continues on the surface (indicated by the arrow) for six 1-h O2 periods each followed by a 1-h air break

Figure 6.

US Navy Diving Manual IWR schedule; the patient breathes O2 at 9 msw (30 fsw) for 60 min for mild DCS (solid line ascent) or 90 min (dashed line ascent) for neurological DCS; the patient continues to breathe O2 during 60-min stops at 6 msw (20 fsw) and 3 msw (10 fsw); O2 breathing continues on the surface (indicated by the arrow) for 3 h

Figure 7.

Clipperton IWR schedule; the patient breathes O2 at the surface for 10 min and, if symptoms do not resolve; descends to 9 msw and continues breathing O2 for 60 min; the patient continues to breathe O2 during the 1 msw·min⁻¹ ascent; O2 breathing continues on the surface (indicated by the arrow) for 6 h

Although recompression with a short delay after symptom onset can effectively treat DCI, it does not guarantee there will not be residual or recurring signs and symptoms. Therefore, IWR conducted without medical supervision should be considered a first-aid measure. The patient should be reviewed by (or at least discussed with) a diving medicine authority at the earliest possible time for a possible evacuation for definitive recompression therapy after IWR is completed. The key elements of a potential decision-making approach to IWR are summarised in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

A flow chart depicting the key steps in decision-making for in-water recompression (IWR)

Conclusions

Despite lack of widespread support within the medical community, divers are being treated with IWR in locations remote from recompression chambers, particularly by groups of 'technical divers'. No data exist to definitively establish the benefits of IWR compared to the more widely supported first-aid treatment of surface O2 and transport to the nearest recompression chamber. Moreover, there are very real risks of IWR that require mitigation. Nonetheless, strikingly good outcomes are achieved with very early recompression, using relatively shallow and short hyperbaric oxygen treatments, such as can be achieved with IWR. These considerations recently led a panel of diving medicine experts reviewing the field management of DCI to state that "in locations without ready access to a suitable hyperbaric chamber facility, and if symptoms are significant or progressing, in-water recompression using oxygen is an option".[ 47]

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest and funding: nil.

Contributor Information

DJ Doolette, Department of Anaesthesiology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

SJ Mitchell, Department of Anaesthesiology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

References

- Vann RD, Butler FK, Mitchell SJ, Moon RE. Decompression illness . Lancet. 2011;377:153–164. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MH, Mitchell SJ. Hyperbaric and diving medicine . In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 19 Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moon RE, Gorman DF. Treatment of the decompression disorders . In: Brubakk AO, Neuman TS, editors. Bennett and Elliott’s physiology and medicine of diving. 5 Edition. Edinburgh: Saunders; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Naval Sea Systems Command . Washington (DC): Naval Sea Systems Command; 2016. [cited 2018 March 02]. US Navy diving manual, Revision 7, SS521-AG-PRO-010 . Available from: http://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/SUPSALV/Diving/US%20DIVING%20MANUAL_REV7.pdf?ver=2017-01-11-102354-393. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds C, Bennett MH, Lippmann J, Mitchell SJ. Diving and subaquatic medicine. 5 Edition. Boca Raton (FL): Taylor and Francis; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds C. Underwater oxygen treatment of DCS . In: Moon RE, Sheffield PJ, editors. Treatment of decompression illness. Proceedings of the 45th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society workshop. Kensington (MD): Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society; 1996. [cited 2018 January 02]. pp. 255–265. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/7999. [Google Scholar]

- Blatteau JE, Pontier JM, Buzzacott P, Lambrechts K, Nguyen VM, Cavenel P, et al. Prevention and treatment of decompression sickness using training and in-water recompression among fisherman divers in Vietnam . Inj Prev. 2016;22:25–32. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Doolette DJ. Recreational technical diving part 1: an introduction to technical diving methods and activities . Diving Hyperb Med. 2013;43:86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dituri J, Sadler R. Lake City (FL): International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers; 2015. In water recompression: emergency management of stricken divers in remote areas . [Google Scholar]

- Blatteau JE, Gempp E, Simon O, Coulange M, Delafosse B, Souday V, et al. Prognostic factors of spinal cord decompression sickness in recreational diving: retrospective and multicentric analysis of 279 cases . Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:120–127. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farm FP, Hayashi EM, Beckman EL. Honolulu (HI): University of Hawaii; 1986. [cited 2018 February 18]. Diving and decompression sickness treatment practices among Hawaii’s diving fishermen. Sea Grant Technical Paper Report No.: UNIHI-SEAGRANTTP-86-001 . Available from: http://nsgl.gso.uri.edu/hawau/hawaut86001.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Moon RE. The natural progression of decompression illness and the development of recompression procedures . [2018 March 03];SPUMS Journal. 1986 2000:36–45. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/5836. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds C. Pearls from the deep. A study of Australian pearl diving 1988-1991 . [2018 March 03];SPUMS Journal. 1996 26(Suppl):26–30. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/6357. [Google Scholar]

- Wong A. Pearl diving from Broome . [2018 March 03];SPUMS Journal. 1996 26(15-25) Available from: http://archive.rubiconfoundation.org/6356. [Google Scholar]

- Westin AA, Asvall J, Idrovo G, Denoble P, Brubakk AO. Diving behaviour and decompression sickness among Galapagos underwater harvesters . Undersea Hyperb Med. 2005;32:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold D, Geater A, Aiyarak S, Juengprasert W, Chuchaisangrat D, Samakkaran A. The indigenous fishermen divers of Thailand: in-water recompression . Int Marit Health. 1999;50:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyle RL, Youngblood D. In-water recompression as an emergency field treatment of decompression illness . [2018 March 03];SPUMS Journal. 1997 27:154–169. Available from: http://archive.rubiconfoundation.org/6083. [Google Scholar]

- Thalmann ED. Principles of U.S. Navy recompression treatments for decompression sickness . Treatment of decompression illness. Proceedings of the 45th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society workshop 1995 . In: Moon RE, Sheffield PJ, editors. Kensington (MD): Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society; 1996. [2018 January 02]. pp. 75–95. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/7999. [Google Scholar]

- Freiberger JJ, Denoble PJ. Is there evidence for harm from delays to recompression treatment in mild cases of DCI? . Management of mild or marginal decompression illness in remote locations. Proceedings of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society workshop 2004 . In: Mitchell SJ, Doolette DJ, Wachholz CJ, Vann RD, editors. Durham (NC): Divers Alert Network; 2005. [2018 January 02]. pp. 70–89. Available from: https://www.diversalertnetwork.org/research/workshops/?onx=3605. [Google Scholar]

- Zeindler PR, Freiberger JJ. Triage and emergency evacuation of recreational divers: a case series analysis . Undersea Hyperb Med. 2010;37:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera JC. Washington DC: Navy Experimental Diving Unit; 1963. [2018 January 02]. Decompression sickness among divers: an analysis of cases. Research Report NEDU TR 1-63 . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MW, Workman RD. Washington DC: Navy Experimental Diving Unit; 1965. [2018 January 02]. Minimal-recompression, oxygen-breathing approach to treatment of decompression sickness in divers and aviators. Research Report NEDU TR 5-65 . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatteau JE, Gempp E, Constantin P, Louge P. Risk factors and clinical outcome in military divers with neurological decompression sickness: influence of time to recompression . Diving Hyperb Med. 2011;41:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayne CG. Acute decompression sickness: 50 cases . JACEP. 1978;7:351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0361-1124(78)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JW, Tichenor J, Curley MD. Treatment of type I decompression sickness using the U.S. Navy treatment algorithm . Undersea Biomed Res. 1989;16:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RW, Flynn ET, Temple DJ. Silver Spring (MD): Naval Medical Research Center; 2002. [2018 January 02]. No-stop 60 fsw wet and dry dives using air, heliox, and oxygen-nitrogen mixtures. Data report on projects 88-06 and 88-06A. Technical Report NMRC 002-002 . Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA452905. [Google Scholar]

- Thalmann ED, Kelleher PC, Survanshi SS, Parker EC, Weathersby PK. Bethesda (MD): Naval Medical Research Center, Joint Technical Report with Navy Experimental Diving Unit, NEDU TR 1-99; 1999. [2018 January 02]. Statistically based decompression tables XI: manned validation of the LE probabilistic decompression model for air and nitrogen-oxygen diving. Technical Report NMRC 99-01 . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3412. [Google Scholar]

- Survanshi SS, Thalmann ED, Parker EC, Gummin DD, Isakov AP, Homer LD. Bethesda (MD): Naval Medical Research Institute; 1998. [2018 January 02]. Dry decompression procedure using oxygen for naval special warfare. Technical Report 97-03 . Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA381290. [Google Scholar]

- Survanshi SS, Parker EC, Gummin DD, Flynn ET, Toner CB, Temple DJ, et al. Bethesda (MD): Naval Medical Research Institute; 1998. [2018 January 02]. Human decompression trial with 1.3 ATA oxygen in helium. Technical Report 98-09 . Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA381290. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RW, Thalmann ED, Temple DJ. Silver Spring (MD): Naval Medical Research Center; 2003. [2018 January 02]. Surface decompression diving. Data report on protocol 90-02. Technical Report NMRC 2003-001 . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4980. [Google Scholar]

- Gerth WA, Ruterbusch VL, Long ET. Panama City (FL): Navy Experimental Diving Unit; 2007. [2018 January 02]. The influence of thermal exposure on diver susceptibility to decompression sickness. Technical Report NEDU TR 06-07.Surface decompression diving. Data report on protocol 90-02. Technical Report NMRC 2003-001 . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/5063. [Google Scholar]

- Doolette DJ, Gerth WA, Gault KA. Panama City (FL): Navy Experimental Diving Unit; 2009. [2018 January 02]. Risk of central nervous system decompression sickness in air diving to no-stop limits. Technical Report NEDU TR 09-03. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/7977. [Google Scholar]

- Doolette DJ, Gerth WA, Gault KA. Panama City (FL): Navy Experimental Diving Unit; 2011. [2018 January 02]. Redistribution of decompression stop time from shallow to deep stops increases incidence of decompression sickness in air decompression dives. Technical Report NEDU TR 11-06. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/10269. [Google Scholar]

- Haas RM, Hannam JA, Sames C, Schmidt R, Tyson A, Francombe M, et al. Decompression illness in divers treated in Auckland, New Zealand, 1996–2012 . Diving Hyperb Med. 2014;44:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RD, Leitch DR. Twenty years of treating decompression sickness . Aviat Space Environ Med. 1987;58:362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianci P, Slade JB, Jr., editors. Delayed treatment of decompression sickness with short, no-air-break tables: review of 140 cases . Aviat Space Environ Med. 2006;77:1003–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay E, Spencer MP, editors. Kensington (MD): Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society; 1999. [2018 January 02]. In-water recompression. Proceedings of the 48th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society workshop 1998 . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/5629. [Google Scholar]

- Butler FK Jr., Thalmann ED. Central nervous system oxygen toxicity in closed circuit scuba divers II.In-water recompression. Proceedings of the 48th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society workshop 1998 . Undersea Biomed Res. 1986;13:193–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler FK Jr, Thalmann ED. CNS oxygen toxicity in closed circuit scuba divers. Technical Report NEDU TR 11-84 . Underwater Physiology VIII. Proceedings of the 8th symposium on underwater physiology . In: Bachrach AJ, Matzen MM, editors. Panama City (FL): Navy Experimental Diving Unit; Bethesda (MD): Undersea Medical Society; 1984. 1978. [2018 January 02]. Reprint of Butler FK Jr, Thalmann ED. CNS oxygen toxicity in closed circuit scuba divers . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3378. [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough OD, Welham W, Brinton ES, Behnke AR. Washington (DC): Navy experimental Diving Unit; 1947. [2018 January 02]. Symptoms of oxygen poisoning and limits of tolerance at rest and at work. Technical Report NEDU TR 1-47 . Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/3316. [Google Scholar]

- Donald KW. 2. Welshpool: The SPA; 1992. Oxygen and the diver . Out of print. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes P. Increasing the probability of surviving loss of consciousness underwater when using a rebreather . Diving Hyperb Med. 2016;46:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gempp E, Louge P, Blatteau J-E, Hugon M. Descriptive epidemiology of 153 diving injuries with rebreathers among French military divers from 1979–2009 . Mil Med. 2011;176:446–450. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Bennett MH, Bird N, Doolette DJ, Hobbs GW, Kay E, et al. Recommendations for rescue of a submerged unresponsive compressed-gas diver . Undersea Hyperb Med. 2012;39:1099–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Doolette DJ, Wachholz CJ, Vann RD, editors. Durham (NC): Divers Alert Network; 2005. [2018 January 02]. Management of mild or marginal decompression illness in remote locations workshop. Proceedings of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society workshop 2004 ; pp. 6–9. Available from: https://www.diversalertnetwork.org/research/workshops/?onx=3605. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle RL. Keeping up with the times: applications of technical diving practices for in-water recompression . In-water recompression. Proceedings of the 48th Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society workshop 1998 . In: Kay E, Spencer MP, editors. Kensington (MD): Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society; 1999. [2018 January 02]. pp. 74–78. Available from: http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/5629. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Bennett MH, Bryson P, Butler FK, Doolette DJ, Holm JR, et al. Pre-hospital management of decompression illness: expert review of key principles and controversies . Diving Hyperb Med. 2018;48:45–55. doi: 10.28920/dhm48.1.45-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]