Abstract

Objective:

To determine if degree of implementation of the Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) program is associated with reductions in hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs).

Design/Setting:

Secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial in 264 SNFs from across the U.S.

Participants:

200 of the 264 SNFs from the randomized trial that provided baseline and intervention data on INTERACT use.

Interventions:

During a 12-month period, intervention SNFs received remote training and support for INTERACT implementation, while control SNFs did not. However, most control facilities were using various components of the INTERACT program before and during the trial on their own.

Measures:

INTERACT use data were based on monthly self-reports for SNFs randomized to the intervention group, and pre-and post-surveys for control SNFs. Primary outcomes were rates of all-cause hospitalizations, hospitalizations considered potentially avoidable (PAH), ED visits without admission, and 30-day hospital readmissions.

Results:

The 65 SNFs (32 intervention and 33 control) that reported increases in INTERACT use had reductions in all cause hospitalizations (0.427 per 1000 resident days; 11.2% relative reduction from baseline, p=<0.001) and PAH (0.221 per 1000 resident days; 18.9% relative reduction, p<0.001). The 34 SNFs (12 intervention and 22 control) that reported consistently low or moderate INTERACT use exhibited statistically insignificant changes in hospitalizations and ED visit rates.

Conclusions:

Increased reported use of core INTERACT tools was associated with significantly greater reductions in all-cause and PAH in both intervention and control SNFs, suggesting that motivation and incentives to reduce hospitalizations were more important than the training and support provided in the trial in improving outcomes. Further research is needed to better understand the most effective strategies to motivate and incentivize SNFs to implement and sustain quality improvement programs such as INTERACT.

Keywords: skilled nursing facilities, potentially avoidable hospitalizations

Introduction

Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) in the United States are under increasing pressure to reduce hospitalizations, hospital readmissions, and emergency department (ED) visits.1–3 These events are associated with multiple hospital-acquired complications, psychological distress among SNF patients/residents and their families, and excess health care costs. Several studies suggest that a substantial proportion of hospitalizations and ED visits from SNFs are potentially avoidable.1–7 Rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations (PAH) are now included in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) 5-Star quality rating system, and hospitals and SNFs are being financially penalized for high rates 30-day readmissions and PAH. In addition, value-based reimbursement strategies, such as Accountable Care Organizations and bundled payments, are incentivizing SNFs to reduce unnecessary hospitalizations and ED visits.3,5,8,9

Over the last decade, CMS, the National Institutes of Health, several foundations, and industry partners have supported the development and testing of interventions to reduce hospitalizations from SNFs. The INTERACT program (Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers) includes a set of tools that address the key factors leading to avoidable hospital admissions and ED visits among SNF residents. INTERACT is based on three core strategies: (1) recognition and management of acute conditions before they become severe enough to require hospitalization; (2) improved communication, documentation, and decision support that allow for effective management in the SNF without hospital admission when safe and feasible; and (3) enhanced advance care planning with use of hospice and palliative care instead of hospitalization when the risks and discomforts of hospital care outweigh the benefits.10,11 A non-randomized collaborative quality improvement project involving 30 volunteer SNFs found a 24% reduction in all-cause hospitalizations among SNFs that actively participated in INTERACT implementation, compared to only a 6% reduction in those that did not.12 Intent to treat analyses from a randomized, controlled trial of training and support for INTERACT implementation involving 264 SNFs from across the U.S. found no significant effects on hospitalization outcomes. Because no effects were seen in the intention to treat analysis, analyses were conducted on a subset of 85 of these SNFs that reported no use of INTERACT before the trial was initiated (33 intervention and 52 control) with the hypotheses that these SNFs would be more likely to show an effect. These analyses demonstrated a significant effect on one of the five outcomes (PAH using CMS definitions4), but this finding did not remain robust to a Bonferroni correction.13

Based on the results of our previous non-randomized trial, we hypothesized that SNFs that reported a higher degree of INTERACT use would have greater reductions in hospitalizations and ED visits than SNFs that reported lower degrees of use.12

METHODS

We performed a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled implementation trial that included a convenience sample of volunteer SNFs.13 Because we did not exclude SNFs that were already using components of INTERACT and could not prevent SNFs from using INTERACT after they were randomized, most of the control SNFs were using INTERACT at various levels before and throughout the trial intervention period. Thus, we included all SNFs in both the intervention and control groups in this analysis. The results of the randomized trial included an intention to treat analysis and an analysis restricted to the SNFs that reported no use of INTERACT at baseline (hypothesizing that we might see an effect in that subgroup). In the present analyses, we grouped the SNFs for which we had both pre and post-intervention data on core INTERACT tool use into three groups: a group that had consistently low to moderate use of INTERACT tools throughout the implementation period (“Low Use” group); a second group that increased use of the tools during the implementation period (“Increased Use” group); and a third group that maintained moderate to high use throughout the implementation period (“High Use” group). Details of the how the groups were defined are included below and in Supplemental Appendix S1.

The institutional review board approved the trial as a quality improvement project.

Study Sample, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

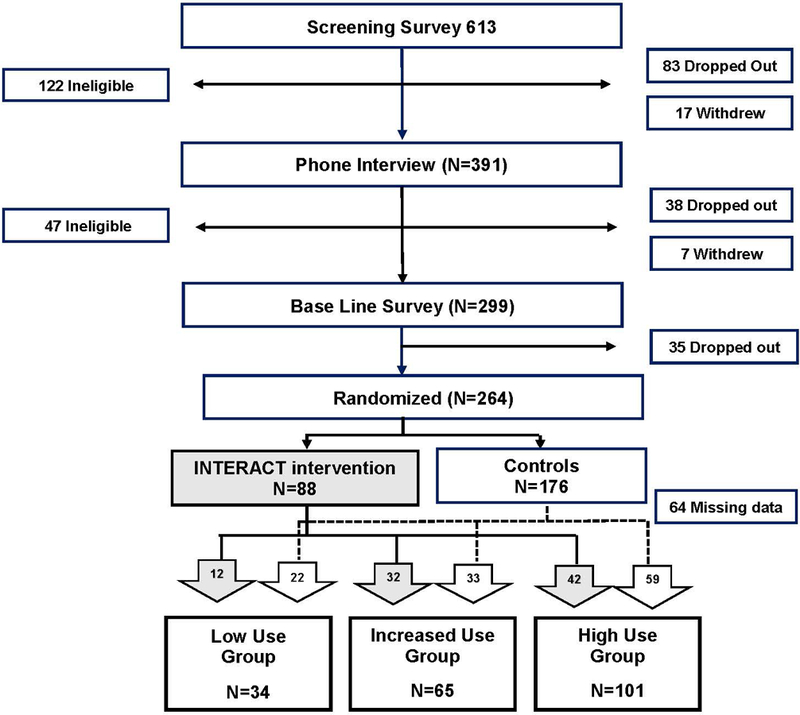

Figure 1 shows the derivation of the SNF sample. SNFs were recruited through collaboration with organizations and chains of SNFs. Inclusion criteria were strong support from SNF leadership, including signing a participation agreement, the ability to safely manage acute changes in condition on-site (availability of on-site medical coverage and laboratory and pharmacy services), and availability of technical support for training and data submission. Exclusion criteria included hospital-based facilities, participation in other projects aimed at reducing hospitalizations, or participation in other major quality improvement efforts that could have impeded INTERACT implementation. Of the 613 SNFs initially screened, 264 were enrolled and randomized to one of three groups: intervention, usual care control with no contact during the 12-month intervention period, and an attention control group, which provided information on efforts to reduce hospitalizations quarterly via an online survey during the 12-month intervention period. The latter group was added in response to a suggestion from the NIH study section for the original grant proposal to account for possible Hawthorne effects of being assessed. The randomization was stratified by SNFs’ initial self-reported level of prior INTERACT use and baseline self-reported 30-day admission rates.

Figure 1 – Flow of Skilled Nursing Facilities into the Study and the Different Use Groups.

Of the 264 facilities originally randomized, 200 provided at least two data points on INTERACT use. The two control groups were combined because in the primary analyses, no differences in outcomes were noted between them. The bottom of the figure illustrates how intervention facilities (in gray) and control facilities were categorized into one of the three INTERACT use groups. Definitions of INTERACT use groups are provided in Supplemental Appendix S1

The Minimum Data Set (MDS) was used to identify patients/residents in each participating SNF and was linked with information on Medicare coverage, demographics, and mortality using the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. The pre-intervention period was January 2012-February 2013 and the intervention period was March 2013-February 2014. Hospitalizations and Medicare-covered SNF stays were identified using the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file. ED visits were identified using outpatient claims files. All data came from Medicare records of beneficiaries with fee-for-service coverage because insurers are not always required to submit claims for Medicare Advantage enrollees.

Intervention

INTERACT training and implementation support were based on experiences with multiple prior educational and quality improvement programs in SNFs using a strategy that could theoretically be emulated and disseminated by a SNF chain, a coalition of SNFs, or a health system and their affiliated SNFs.14–17 Each intervention SNF selected a project “champion” and “co-champion” who were responsible for facilitating INTERACT training and implementation, including periodic submission of facility-based data and participation in training webinars monthly phone calls. The study team provided each intervention facility with INTERACT tools, an online training curriculum, and a series of webinar sessions on the use of INTERACT tools. SNF champions were asked to participate in monthly telephone calls, and to submit data on hospital transfers using the INTERACT hospitalization tracking tool, root-cause analyses on transfers using the INTERACT Quality Improvement Review tool, and online forms describing acute changes in condition that did not result in transfer to the hospital within 48 hours. These data were displayed in graphs and results interpreted for each intervention SNF quarterly, and summarized for the group on periodic webinars. Study progress and challenges were discussed during the webinars and on monthly phone calls.

Measures

Self-reported use of two core INTERACT tools was used to categorize SNFs by degree of program implementation. All participating SNFs in the randomized trial completed a baseline structured telephone survey that asked about the use of seven core INTERACT tools. SNFs were asked to categorize use as “no use”, “use in part of the facility or intermittently”, or “regular use of the tool throughout the facility”. These tools included the early warning “Stop and Watch”; the Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) Communication Form and Progress Note; the Hospitalization Tracking tool; the root-cause analysis Quality Improvement Review tool; the Hospital Transfer Form; the decision support tools (Care Paths and Change in Condition File Cards); and the Advance Care Planning tools.10–12 SNFs randomized to the intervention group reported use of core INTERACT tools during monthly structured telephone calls with project staff. SNFs randomized to the control groups were asked to rate their use of INTERACT tools using the same scale via an online survey at the end of the 12-month intervention period. For the analyses, we used data on two of the seven core tools, the Stop and Watch and the SBAR Communication Form and Progress Note, because they are fundamental to the program and the most commonly used. Facilities were categorized into three groups based on changes in use over the 12-month intervention period: one group reported consistent low or moderate use without an increase in use (“Low Use”); a second group reported increases in use (i.e., from low use at baseline to moderate or high usage; “Increased Use”; and a third group reported high or moderate use at both baseline and follow-up (“High Use”). Supplemental Appendix S1 provides details on how SNFs were categorized into these three groups.

The primary outcome was the rate of hospitalizations per 1000 resident days. We examined other outcomes including rates of PAH using CMS definitions; 30-day readmission rates, and rates of ED visits that did not result in hospital admission. CMS defines PAH using multiple diagnoses, including urinary tract infection, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease/asthma, dehydration, and cellulitis, among many others.4

The analyses controlled for baseline SNF characteristics that could theoretically affect hospitalization rates. These characteristics included rural location; number of Medicare certified beds, for-profit status; the number of certified nursing assistant, licensed practical nurse, and registered nurse hours per resident day reported at baseline (in 2012); occupancy rate; percent long-stay residents; and quality performance on Nursing Home Compare (top quartile of composite inspection score and a rating of 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale for overall, survey and quality ratings). We also adjusted for resident characteristics, including age (expressed as a set of binary variables indicating whether an individual was aged 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, or 90+), gender, race and ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility, level of comorbidity (measured using the CMS hierarchical condition category (HCC) risk factor score18), any Part A stay and total Part A days, and functional status reported on the MDS, including activities of daily living (ADLs) (using binary variables indicating whether a resident exhibited an ADL score of 0–4, 5–8, 9–12, or 13–16, where lower scores indicate greater functional status)19 and the cognitive performance scale, expressed using binary variables for whether an individual exhibited a score of 0–2 (intact to mild impairment), 3–4 (moderate or moderately severe impairment), or 5–6 (severe or very severe impairment).20

Statistical Analyses

The unit of analysis was a facility-month. For each outcome measure, we created adjusted rates per 1000 resident days at the resident-level that adjusted for baseline facility and patient/resident characteristics, separately in each month. We calculated average outcome rates at the facility-month level as the average of adjusted resident-level rates in each month. The final analytic data was comprised of facility-month observations in the 14 months prior to the intervention and the intervention year. Our analytic framework employed a differences-in-differences approach that computed differential changes in outcomes for the Increased and High Use groups relative to the Low Use group. To do this, we estimated linear regressions that included facility fixed effects (i.e., separate binary variables controlling for each SNF in the sample), an “intervention period” indicator, and interaction terms indicating the Increased or High Use groups during the intervention period. In secondary analysis, we allowed changes in each group of SNFs to differ based on intervention status. We clustered standard errors at the SNF-level to account for the correlation of regression errors within SNFs over time.

RESULTS

Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of the three INTERACT use groups and the 64 SNFs with missing data. As shown in Figure 1, we did not have baseline and follow-up data on INTERACT tool use in 64 of the 264 SNFs that participated in the randomized trial: two in the intervention group (who dropped out of the trial) and 62 in the control groups (who chose not to participate in the follow-up phase of the trial). The only statistically significant differences (p<0.05) across the three INTERACT groups were that the Low Use group reported higher licensed practical nurse hours per resident day and had a higher percentage of non-profit facilities than the other groups. Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of the patients/residents and the baseline rates of hospitalization outcomes. There were multiple statistically significant differences between the three groups.

Table 1 –

Baseline Skilled Nursing Facility Characteristics by INTERACT Use Groups

|

Low Use Group N = 34 |

Increased Use Group N = 65 |

High Use Group N = 101 |

SNFs with Missing Data1 N = 64 |

P-value (Differences Among the Groups 1–3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Characteristics | |||||

| Rural (%) | 6% | 20% | 12% | 13% | 0.092 |

| For-profit (%) | 44% | 66% | 66% | 58% | 0.062 |

| Non-profit (%) | 56% | 31% | 33% | 39% | 0.037 |

| Government (%) | 0% | 3% | 1% | 3% | 0.222 |

| Certified beds | 128 (52) | 142 (72) | 137 (59) | 140 (77) | 0.555 |

| Occupancy rate | 0.91 (0.20) | 0.89 (0.14) | 0.86 (0.15) | 0.89 (0.13) | 0.202 |

| Proportion of resident days that were long-stay2 |

0.64 (0.14) | 0.63 (0.15) | 0.64 (0.13) | 0.65 (0.13) | 0.928 |

| Staff hours per resident day | |||||

| Certified nursing assistant (CNA) |

2.39 (0.53) | 2.52 (0.67) | 2.40 (0.56) | 2.48 (0.47) | 0.459 |

| Licensed practical nurse (LPN) |

0.98 (0.34) | 0.84 (0.36) | 0.80 (0.32) | 0.82 (0.31) | 0.031 |

| Registered nurse (RN) | 0.86 (0.40) | 0.76 (0.32) | 0.80 (0.34) | 0.78 (0.31) | 0.441 |

| Quality performance3 | |||||

| Overall quality of 4 or 5 | 68% | 51% | 61% | 53% | 0.213 |

| Survey rating of 4 or 5 | 47% | 25% | 37% | 47% | 0.062 |

| Quality rating of 4 or 5 | 82% | 86% | 89% | 89% | 0.616 |

Notes:

Data reported as percentages or means and standard deviations. N represents unique facilities. Robust standard errors are applied.

Definitions on INTERACT use groups are provided in Supplemental Appendix S1.

These facilities did not report data and use of Stop and Watch or SBAR at baseline or follow up.

Long-stay defined as the proportion of total 2012 resident days that are more than 100 days into a stay.

Quality performance measures come from 2012 Nursing Home COMPARE data.

Table 2 –

Resident Characteristics and Outcomes by INTERACT Use Groups

|

Low Use N = 34 |

Increased Use N = 65 |

High Use N = 101 |

SNFs with Missing Data1 N = 64 |

P-value (Differences Among Groups 1–3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline resident characteristics (Jan. 2012-Feb. 2013) | |||||

| Unique resident- facility pairs |

10,187 | 17,841 | 26,884 | 17,846 | |

| Age (years) | 81.6 (10.2) | 80.9 (10.8) | 79.6 (11.5) | 81.6 (10.6) | 0.007 |

| Female (%) | 68% | 65% | 63% | 66% | 0.004 |

| White non-Hispanic (%) |

83% | 82% | 78% | 89% | 0.567 |

| Black non-Hispanic (%) |

15% | 16% | 15% | 7% | 0.952 |

| Hispanic (%) | 1% | 1% | 3% | 1% | 0.003 |

| Asian/other (%) | 1% | 1% | 4% | 2% | 0.030 |

| Hierarchical Care Category Score2 |

1.33 (1.13) | 1.46 (1.22) | 1.48 (1.25) | 1.43 (1.18) | 0.029 |

| Dual Medicare/Medicaid status (%) |

22% | 29% | 36% | 29% | 0.003 |

| Any Part A days (%) |

76% | 70% | 73% | 72% | 0.101 |

| Total Part A days (in period) |

24.0 (26.3) | 25.4 (30.5) | 25.9 (29.3) | 24.4 (27.6) | 0.208 |

| Late Loss Activity of Daily Living (ADL) Score (range: 0 – 16) |

7.4 (4.2) | 7.9 (4.6) | 7.6 (4.4) | 8.2 (4.6) | 0.267 |

| Complete dependence, any late loss ADL (ever in period) (%) |

18% | 23% | 22% | 21% | 0.369 |

| Terminal diagnosis (ever in period) (%) |

4% | 4% | 4% | 6% | 0.939 |

| Severe cognitive disability (%)3 |

9% | 9% | 11% | 9% | 0.430 |

| Outcome Rates during Baseline (Jan. 2012-Feb. 2013) | |||||

| All cause hospitalizations |

3.53 (1.59) | 3.81 (1.49) | 3.62 (1.47) | 3.57 (1.36) | 0.149 |

| Potentially avoidable hospitalizations |

1.09 (0.82) | 1.17 (0.80) | 1.14 (0.73) | 1.10 (0.73) | 0.606 |

| ED visits without admission |

1.86 (1.21) | 2.14 (1.17) | 1.89 (1.19) | 1.90 (1.03) | 0.041 |

| Readmission rate | 0.20 (0.18) | 0.21 (0.16) | 0.21 (0.16) | 0.21 (0.15) | 0.394 |

| Outcome Rates during Intervention (Mar. 2013-Feb. 2014) | |||||

| All cause hospitalizations |

3.44 (1.53) | 3.39 (1.36) | 3.37 (1.41) | 3.29 (1.28) | 0.921 |

| Potentially avoidable hospitalizations |

1.02 (0.76) | 0.95 (0.72) | 1.00 (0.68) | 0.94 (0.66) | 0.558 |

| ED visits without admission |

1.94 (1.17) | 2.07 (1.09) | 1.79 (1.09) | 1.95 (1.10) | 0.009 |

| Readmission rate | 0.19 (0.17) | 0.20 (0.17) | 0.20 (0.17) | 0.20 (0.17) | 0.672 |

Notes:

Definitions on INTERACT use groups are provided in Supplemental Appendix S1.

Resident characteristics are reported as percentages or means (unweighted) and standard deviations. N represents unique facilities. Data on outcomes (from facility-month level data) are reported as means (weighted by total resident days, except for readmission rate, the means of which are weighted by the number of index hospitalizations) and standard deviations. Outcomes are measured by per 1,000 resident days (except for readmission rate, which is a proportion of index hospitalizations that were associated with a hospital readmission within 30 days), adjusted for resident and facility characteristics. For example, rates of 3.0–4.0 for all cause admissions in a typical SNF with a resident census of 100 would mean 3–4 hospital admissions every 10 days. Standard errors are clustered at the SNF level.

64 facilities did not report data and use of Stop and Watch or SBAR at baseline or follow up.

Hierarchical Condition Category score ranges from 0.12 to 13.52; 1st percentile, median, and 99th percentile are 0.30, 0.95 and 5.80 respectively.

MDS-derived Cognitive Performance Scale Score = 5, 6.

Table 3 shows the mean values for the hospitalization measures in all SNFs in the baseline period and during the 12-month intervention period. The table also exhibits differences in changes in these outcomes between the groups. Decreases in all-cause hospitalizations and PAH were significantly greater in the Increased Use group relative to changes in the Low Use group (p=0.005 and 0.022, respectively). Reductions in ED visits without admission were greater for the High Use compared to the Low Use group, but did not reach significance at the 0.05 level (p=0.071).

Table 3 –

Relative Changes in Outcomes from Baseline to the 12-month Intervention Period by INTERACT Use Group

| All cause hospitalizations |

Potentially avoidable hospitalizations |

ED visits without admission |

Readmission rate |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Outcome mean during Baseline (Jan. 2012-Feb. 2013) [SD] |

3.673 [1.499] |

1.143 [0.772] |

1.970 [1.190] |

0.209 [0.164] |

|

Outcome mean during Intervention (Mar. 2013-Feb. 2014) [SD] |

3.388 [1.413] |

0.987 [0.708] |

1.912 [1.111] |

0.199 [0.168] |

|

Change for the Low Use Group (N=34) (p-value) |

−0.056 (0.615) |

−0.052 (0.390) |

0.071 (0.367) |

−0.003 (0.818) |

|

Change for Increased Use Group (N=65) relative to the Low Use Group (p-value) |

−0.371*** (0.005) |

−0.169** (0.022) |

−0.146 (0.140) |

−0.007 (0.668) |

|

Change for the High Use Group (N=101) relative to the Low Use Group (p-value) |

−0.187 (0.133) |

−0.086 (0.200) |

−0.165* (0.071) |

−0.008 (0.624) |

Notes:

Definitions on INTERACT use groups are provided in Supplemental Appendix S1.

All outcomes are measured by per 1,000 resident days, adjusted with resident and facility characteristics and weighted by total resident days (except for readmission rate). The readmission rate is measured as a proportion of index hospitalizations that were associated with a hospital readmission within 30 days. Each cell in the third to fifth row displays a coefficient estimate and a p-value in parentheses from regressions of adjusted outcomes on a “during intervention” indicator, group indicators interacted with the “during intervention” indicator, and SNF fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the SNF level.

indicate significance at 1% level respectively.

indicate significance at 5% level respectively.

indicate significance at 10% level respectively

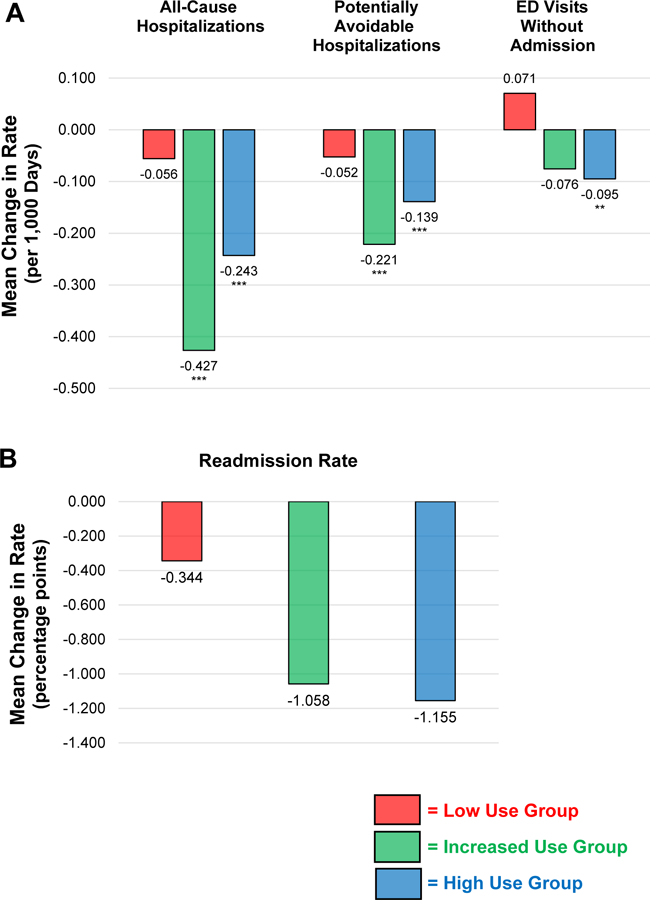

Figure 2 illustrates the mean absolute changes in hospitalization and ED rates between the baseline and intervention periods, based on the results in Table 3. Translated into percentage terms, the Increased Use group exhibited an 11.2% relative reduction in all cause hospitalizations and an 18.9% relative reduction in PAH (both p<.001), compared to non-significant relative reductions of 1.6% and 4.8% in the Low Use group (Figure 2a). In a separate analysis, we found no differential reduction in all cause hospitalizations or PAH between intervention and control facilities in the Increased Use group. Thirty-day readmission rates did not change by more than 1.5 percentage points in any of the Groups and changes were statistically insignificant (Figure 2b).

Figure 2 – Changes in hospitalization and ED outcomes by INTERACT use groups.

Panel A represents the mean absolute change in outcomes from the baseline period to the intervention period with rates measured in events per 1,000 patient/resident days. Panel B represents the change from baseline rates in the percent of SNF admissions who were readmitted to the acute hospital within 30 days. Rates during the baseline and intervention periods are illustrated in Table 2. ***, ** and * indicate significance at 1%, 5% and 10% level respectively, based on absolute changes. Red = Low Use Group, Green = Increased Use Group, Blue = High Use Group

DISCUSSION

This secondary analysis complements and extends the primary analysis of the randomized controlled trial of training and implementation support for the INTERACT quality improvement program, and the results related to INTERACT use are consistent with findings from an earlier uncontrolled study.12 The results have important implications for successful dissemination and maintenance of quality improvement programs in the SNF setting.

The randomized implementation trial found that the training and implementation support provided had no significant effect on hospitalizations or ED use. While the estimates did suggest a reduction in PAH, they were not robust to a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.13 In the current study, we found reductions in all-cause hospitalizations and PAH among SNFs that reported increased use of core INTERACT tools relative to SNFs with consistently low use of these tools. This finding is consistent with our previous uncontrolled study in which SNFs more engaged in INTERACT implementation had significantly greater reductions in all-cause hospitalizations.12 The unique finding in the current study is the significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations and PAH in SNFs voluntarily adopting INTERACT, including both facilities that did and did not receiving training and implementation support. Differences across facilities and residents among the INTERACT use groups do not appear to explain these findings. The relative greater reduction in hospitalizations among facilities reporting increasing INTERACT use, and the lack of a reduction among facilities randomly assigned to receive training and implementation support, suggests that motivation and incentives to reduce hospitalizations may be an important factor in explaining these results. SNFs that increased INTERACT use—especially those in the control group—may have been more motivated to improve hospitalization outcomes by incentives in their local environment. At the time we initiated this trial, many SNFs were in fact under increasing pressure to reduce hospitalizations, especially 30-day readmissions, because of increasing penetration of value-based payment programs (e.g. Medicare managed care, Accountable Care Organizations), and their referring hospitals were preparing for financial penalties for high 30-day readmission rates and bundled payment programs. Since many SNFs depend on Medicare Part A stays for their financial viability, these local environmental factors may have provided SNFs with strong motivation to reduce hospitalizations. We also identified several other facilitators and barriers to INTERACT implementation based on information obtained from the monthly telephone calls with the facility-based champions.21 Other studies have also identified factors associated with PAH, including the importance of nurse-physician communication clinical information to covering physicians, and availability of lab services.22,23

Several strategies for training and support for implementing quality improvement programs and tools such as INTERACT may further improve outcomes. A CMS demonstration project involving seven sites working with over 140 SNFs to reduce hospitalizations of long-stay SNF residents reported significant reductions in PAH.24 All of these sites used components of the INTERACT program and provided on-site training and implementation support using advanced practice nurses and nurse practitioners. One site that employed nurse practitioners to support INTERACT implementation achieved a 30% reduction in all-cause hospitalizations.25 Telemedicine is another strategy that can enhance the capability to implement quality improvement and clinical programs in SNFs, providing in-person assessment and recommendations via live interactions with staff, residents, and families.26 Embedding INTERACT and other similar programs and tools into electronic health records in the workflow of SNF staff can also facilitate decision support and the capability of staff to assess and manage patients/residents without hospital transfer.27

Our study had a number of limitations. First, we lacked complete data on INTERACT use over the study period for 64 out of 264 SNFs in our sample. This likely resulted in some bias in our results. For example, SNFs that dropped out of the study may have been struggling to implement INTERACT due to competing priorities, which would bias the results towards better outcomes. Alternatively, SNFs that dropped out may been very successful in reducing hospitalizations and felt they did not need our training and implementation support, which would bias the results in the opposite direction. We could not ascertain the reasons that SNFs dropped out of the study, so we do not know which of these biases may have been stronger. Second, the validity of reports of INTERACT use via telephone calls and online surveys may be subject to social response bias and other inaccuracies. Third, while INTERACT training and implementation support were randomly assigned, actual program implementation was not, and thus we were unable to isolate the effect of increasing INTERACT use from other factors that could be correlated with both adoption and hospitalization and ED outcomes.

In summary, increased reported use of core INTERACT tools was associated with significantly greater reductions in all-cause and PAH in both intervention and control SNFs, suggesting that motivation and incentives to reduce hospitalizations were more important in improving outcomes than the training and support provided in the trial. Further research is needed to better understand the most effective strategies to motivate and incentivize SNFs to implement and sustain quality improvement programs such as INTERACT.

Supplementary Material

Definitions of the INTERACT use groups.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Ouslander is a full-time employee of Florida Atlantic University (FAU) and has received support through FAU for research on INTERACT from the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Commonwealth Fund, the Retirement Research Foundation, the Florida Medical Malpractice Joint Underwriting Association, PointClickCare, Medline Industries, and Think Research. Dr. Ouslander and his wife had ownership interest in INTERACT Training, Education, and Management (“I TEAM”) Strategies, LLC, which had a license agreement with FAU for use of INTERACT materials and trademark for training during the time of the study, and now receive royalties from Pathway Health, which currently holds the license. Dr. Ouslander serves as a paid advisor to Pathway Health, Think Research, and Curavi.

Sponsors Role

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Nursing Research (1R01NR012936) and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02177058). Medline Industries provided support for components of an online training program used during the study.

Other Acknowledgements

The authors thank the SNFs and SNF staff that participated in the study, and Jill Shutes, David Wolf, Laurie Herndon, and Alice Bonner for assistance with training and implementation support. We also thank Mark Woodhouse for programming support.

Grant support: National Institute for Nursing Research (1R01NR012936)

Footnotes

Impact statement: We certify that this work is novel. It is a secondary analysis of the first randomized implementation trial of the INTERACT program. Specifically, it estimates the association of the degree of INTERACT implementation with reductions in hospitalizations among skilled nursing facilities participating in the trial. The data support previous research that suggest that the more robust implementation of quality improvement programs such as INTERACT result in better outcomes. These data have important implications for the dissemination of such programs in the skilled nursing facility setting.

Conflicts of Interest

Work on funded INTERACT research is subject to the terms of Conflict of Interest Management plans developed and approved by the FAU Financial Conflict of Interest Committee.

None of the other authors have any conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Affairs 2010;29(1):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents: Frequency, Causes, and Costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2010;58(4):627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouslander JG, Berenson RA. Reducing unnecessary hospitalizations of nursing home residents. N Engl J Med 2011;365(13):1165–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh EG, Wiene JM, Haber S, Bragg A, Freiman M, Ouslander JG. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries from nursing facility and Home- and Community-Based Services waiver programs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(5):821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouslander J, Maslow K. Geriatrics and the Triple Aim: Defining Preventable Hospitalizations in the Long Term Care Population. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(12):2313–2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General. Medicare Nursing Home Hospitalization Rates Merit Additional Monitoring 2013;November 2013(OEI-06–11-00040).

- 7.Burke R, Rooks S, Levy C, Schwartz R, Ginde A. Identifying potentially preventable emergency department visits by nursing home residents in the United States. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16(5):395–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carnahan JL, Unroe KT, Torke AM. Hospital Readmission Penalties: Coming Soon to a Nursing Home Near You! Journal of American Geriatrics Society 2016;64:614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program 2016; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html Accessed 9/28/2017.

- 10.Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15(3):162–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathway Health 2018; http://www.pathway-interact.com Accessed 5/13/2018.

- 12.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to Reduce Hospitalizations from Nursing Homes: Evaluation of the INTERACT II Collaborative Quality Improvement Project. Journal of American Geriatrics Society 2011;59:745–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kane RL, Huckfeldt PJ, Tappen R, et al. Effects of an Intervention to Reduce Hospitalizations From Nursing Homes: A Randomized Implementation Trial of the INTERACT Program. JAMA Internal Medicine 2017;177(9):1257–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meehan TP, Qazi DJ, Van Hoof TJ, et al. Process Evaluation of a Quality Improvement Project to Decrease Hospital Readmissions from Skilled Nursing Facilities. Journal of American Medical Directors Association 2015;16:648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnelle JF, Ouslander JG, Cruise PA. Policy without technology: a barrier to improving nursing home care. Gerontologist 1997;37(4):527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnelle JF, Cruise PA, Rahman A, Ouslander JG. Developing rehabilitative behavioral interventions for long-term care: Technology transfer; acceptance; and maintenance issues. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1998;46:771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman A, Schnelle J, Yamashita T, Patry G, Prasauskas R. Distance Learning: A Strategy for Improving Incontinence Care in Nursing Homes. Gerontologist 2010;50(1):121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, Ash AS, et al. Risk Adjustment of Medicare Capitation Payments Using the CMS-HCC Model. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review 2004;25(4):119–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris J, Morris S. ADL assessment measures for use with frail elders. Journal of Mental Health and Aging 1997;3(1):19–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JA, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences 1994;49(4):M174–M182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tappen R, Wolf D, Rahemim Z, al. e. Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing a Change Initiative in Long-Term Care Utilizing the INTERACT™ Quality Improvement Program. The Health Care Manager 2017;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young Y, Baryhdt NR, Broderick ea, et al. Factors Associated with Potentially Preventable Hospitalization in Nursing home Residents in New York State: A Survey of Directors of Nursing. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58(5):901–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young Y, Inamdar S, Dichter BS, et al. Clinical and Nonclinical Factors Associated With Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations Among Nursing Home Residents in New York State. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;2011(12):364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingber MJ, Feng Z, Khatutsky G, Wang JM, et al. Initiative To Reduce Avoidable Hospitalizations Among Nursing Facility Residents Shows Promising Results. Health Affairs 2017;36(3):441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rantz MJ, Popejoy L, Vogelsmeier A, et al. Successfully Reducing Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents: Results of the Missouri Quality Initiative. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18(11):960–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grabowski DC, O’Malley AJ. Use of Telemedicine Can Reduce Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents and Generate Savings for Medicare. Health Affairs 2014;33(2):244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handler S, Sharkey S, Hudak S, et al. Incorporating INTERACT II Clinical Decision Support Tools into Nursing Home Health Information Technology. Annals of Long Term Care and Aging 2011;19:23–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Definitions of the INTERACT use groups.