Abstract

Purpose

To explore how academic physicians perform social and professional identities and how their personal experiences inform professional identity formation.

Method

Semi-structured interviews and observations were conducted with 25 academic physicians of diverse gender and racial/ethnic backgrounds at the University of Utah School of Medicine from 2015–2016. Interviews explored the domains of social identity, professional identity, and relationships with patients and colleagues. Patient interactions were observed. Interviews and observations were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using grounded theory.

Results

Three major themes emerged: physicians’ descriptions of identity differed based on social identities, as women and racially/ethnically minoritized participants linked their gender and racial/ethnic identities, respectively, to their professional roles more than men and White, non-Latino/a participants; physicians’ descriptions of professional practice differed based on social identities, as participants who associated professional practices with personal experiences often drew from events connected to their minoritized identities; and physicians’ interactions with patients corresponded to their self-described actions.

Conclusions

Professional identity formation is an ongoing process and the negotiation of personal experiences is integral to this process. This negotiation may be more complex for physicians with minoritized identities. Implications for medical education include providing students, trainees, and practicing physicians with intentional opportunities for reflection and instruction on connecting personal experiences and professional practice.

Modern medicine, which emerged over the last century following the release of the Flexner report in 1910,1 has a distinct professional culture2 including specialized vocabulary, ways of dressing,3,4 and social norms for interacting with colleagues and supervisors.5 Competency-based education has further codified this culture, calling for future physicians to become the “right kind of physician”5 with an “appropriate professional identity.”6 Becoming a physician is not just about learning how to diagnose and treat disease, but also about adopting and internalizing the values and ethos of medical culture so that over time, one’s sense of self is transformed.4 This process of becoming has been of great interest to the field of medical education.7,8

Theories of physician professional identity formation suggest that the process is developmental, multifaceted, and nonlinear.4,8–10 Theoretical studies emphasize how the formation from pre-professional to professional involves the integration of personal history and professional roles.4,5,8,10–13 As Jarvis-Selinger argues,4 this professional formation is the process of learning how to “be.” Empirical studies show that professional identity formation involves continual development14,15 and the integration of personal and professional experiences.7,15

Theoretical models of professional identity formation also posit that the standard professional identity for physicians in the United States is based on the group that has historically populated medicine: White, non-Latino men.8 As the de facto comparator identity, White, non-Latino male physicians are generally referred to simply as “doctors,” whereas modifiers are often used to describe other physicians (e.g., female doctor, Asian doctor). The effect of this normative approach to physician professional identity formation is unwelcoming. Although the racial and gender composition of the physician population in the United States is changing, individuals from non-majority backgrounds still experience the profession differently.8,10,13,16–18

While many studies of identify formation have focused on medical students and trainees,14,15 our work, like that of Cope and colleagues,7 examines practicing physicians’ understandings of personal and professional identity. Following up on work by Case and Brauner,3 who argue that learning to become a physician involves understanding how to perform as a physician, we used performance studies as a framework to explore how academic physicians’ self-described identities and actions can illuminate the conceptualization of professional identity formation, particularly with respect to how physicians’ differing social identities may influence or interact with their professional identity formation.

The interdisciplinary field of performance studies draws from fields including theater, anthropology, sociology, and education to understand how individuals interact with others. We are not suggesting that physicians are pretending to be doctors, but rather that physicians learn how to be doctors through repetition and practice while receiving feedback from preceptors and patients. Physicians-in-training learn how to think, talk, and act as physicians in order to perform as physicians. Case and Brauner3 posit: “Arguing that a medical professional is performing a role is not an accusation of fakery but, rather, an acknowledgment of learned behaviors developed to meet critical objectives.” Because even experienced physicians continue to receive feedback about their actions, identity performances are not static, but dynamic. Moreover, performances refer to how we act and how we talk about our actions and identities.

Our purpose was to explore academic physicians’ performances of social and professional identity to understand how professional identity formation is influenced by both social and professional contexts. Social identities such as race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation shape our “social realities.”19 Professional identity is a blend of one’s personal values and behaviors (which include social identity) and the shared values and behaviors of the profession.7 Specifically, we explored physicians’ told identity performances (how they talk about themselves) and physicians’ lived identity performances (how they act). In exploring told identity performances, we asked how physicians described social identities within professional contexts and (2) how physicians described their professional practices in relation to their social identities. In exploring lived identity performances, we asked how their interactions with patients compare to self-described practices (told identity).

Method

We employed a qualitative collective case study design20,21 to understand how physicians’ perceptions of their identities influenced their approaches to patient care. This design allowed for examining multiple individuals within a system such as a health care system. We conducted the study at the University of Utah School of Medicine, and collected interview and observational data from 25 physicians between November 2015 and December 2016. We obtained approval for the study from our institution’s institutional review board.

Study design and recruitment

Three members of the research team (C.J.C., C.L.B., A.M.L.) developed the research questions and the recruitment strategy. Of these researchers, C.J.C. received postdoctoral funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) to study the identity performances of physician-scientists. For this reason, we were originally interested in recruiting physicians who conduct research at the institution’s National Institutes of Health-supported center for clinical and translational science (CCTS). We were also interested in understanding whether physicians from minoritized backgrounds (defined below) performed professional identities differently from physicians from non-minoritized backgrounds and thus we also sought to enroll physicians from diverse backgrounds with respect to gender and race/ethnicity. Using purposeful sampling,22 we sent a recruitment email to 11 physicians from diverse racial and gender backgrounds who are part of the CCTS, requesting participation in a study on physician identities and patient interactions Five agreed to participate. To recruit additional participants, we used snowball sampling by asking the five who had already agreed to participate to recommend a colleague for the study. Of these 7 recommended colleagues, all agreed to participate. We also invited physicians from a university sponsored grant-writing mentoring program23 who conduct clinical and translational research (11/23 agreed to participate). In order to enroll a diverse sample, we also obtained a list of faculty from the faculty affairs office to aid in identifying participants (2/2 agreed to participate). We recruited until we identified participants from a variety of racial/ethnic groups from different genders and reached thematic saturation, resulting in a final sample of 25 physicians.

We use the term “minoritized”24 to refer to participants who self-identified with racial and gender groups that have historically suffered systematic oppression in the United States.19 This included non-White participants who identified as Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Asian or Asian American, Hispanic or Latino/a, or multiracial, as well as participants from all racial groups who identified as women (no one self-identified as gender non-conforming). After much discussion, we agreed to use the term “minoritized” rather than “minority,” because minoritized reflects our understanding that identities are socially constructed. The term “non-minoritized” refers to White, non-Latino participants and to men, groups that have historically received privilege in the United States19 and in the medical field and are considered the comparator group for other physicians5,10 Though we explored race and gender as distinct identities, we recognize that identities are intersectional24,25 and that individuals may identify as minoritized with respect to one identity while identifying as non-minoritized in another, meaning that White women can identify as both non-minoritized and minoritized.

Data collection

Two members of the team (C.J.C. and L.M.O.) who are experienced qualitative researchers, designed and tested the semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix 1), which was adapted from Chow’s26 study on teacher identities and pedagogies and covered the domains of social identity, professional identity, and relationships with patients and colleagues. After obtaining informed consent, C.J.C. conducted the interviews with the physician participants. Probes were used to elicit additional information from participants about their understandings of identity and its relation to clinical practice. Each interview was approximately 60 minutes, conducted in participants’ private offices, and transcribed verbatim. Each interview, excepting one (due to time constraints), covered all interview protocol questions. The same author (C.J.C.) conducted the clinical care observations. The observations were meant to capture how participants interacted with their patients in order to provide data on physicians’ lived experiences. We aimed for two clinical care observations per participant, so each study physician identified at least two patients. Observations were conducted shortly after the interviews were completed, and patient participants were generally invited based on timing (e.g., the next possible clinic day that worked for the investigator). All invited patient participants agreed and consent was obtained before the observation occurred. During the physician-patient interaction, C.J.C. was located in a corner of the exam room, took notes, and recorded the conversation, which was transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Interview coding

Following the principles of grounded theory,22 we coded the interviews and observations for emerging themes. Our process was iterative and team-based.

C.J.C. led the coding by analyzing interview transcriptions line-by-line and creating initial codes using Dedoose Version 7.0.23 software (Los Angeles, CA). Interviews were coded as they were transcribed, and as each interview was analyzed, constant comparative methods22 were used to further refine the codes. During focused coding, codes were sorted, expanded, collapsed, and further refined. The final codebook contained five main codes (identities, care delivery, mentoring, administrative roles, and research) with 65 sub-codes, definitions, and example quotes. Using this codebook, the lead author (C.J.C.) and two trained investigators (K.R. and S.Z.) coded the first seven transcripts and discussed discrepancies to ensure that we had a shared understanding of the codes. The remaining 18 transcripts were each coded twice (by the first author and either K.R. or S.Z.) to ensure that different interpretations of the data were explored. We resolved discrepancies through weekly discussion27 throughout the coding process.

After finalizing the coding analysis using the five codes, we returned to our first two research questions, which ask how physicians describe social identities within professional contexts and how physicians describe professional practices with respect to social identities. Concentrating on these questions, we examined two codes—identities and care delivery—more closely for sub-themes. Seeing that there was a connection between how participants came to define their identities and how these identities influenced care, we (C.J.C., K.R., S.Z.) recoded all transcripts using two additional codes—defining experiences and connections—in order to further understand physicians’ understandings of identity and practice. Though we did not find that this additional coding process produced findings that warrant discussion in the results section, it confirmed that social and professional experiences are connected.

Observations analysis

Since our goal was to see whether participants’ told performances (from the interviews) matched their lived performances (from the clinical observations), our approach to coding the observation transcripts was more deductive.28 C.J.C. and K.R. coded the observation transcripts using the interview codes in order to see how physicians’ actions with patients compared to their self-described practices. Actions were deemed comparable when they referred back to a statement from the interview.

Ensuring trustworthiness

The rigor of the investigation was enhanced by multiple techniques, including immersion in the data, memo-writing,22 and peer debriefing29 between the first author and third author on a monthly basis and the first author and the second and senior authors every six to eight weeks. Lastly, we employed member checking22 in order to obtain participants’ feedback regarding the reliability of our findings. A third of the way through the study, after ten participants’ interviews were analyzed, we sent a summary of the findings to the ten participants to assess whether findings were aligned with participants’ experiences. Seven of the ten participants provided feedback. At the end of the study, after all interviews and observations were analyzed, we distributed a summary of findings to all participants. This time, nine of the 25 participants provided feedback (five of whom had not provided feedback during the first member check). Both times, participants indicated that our findings affirmed their experiences.

Results

Our study explored how academic physicians perform professional identities. We enrolled 25 physicians (Table 1). Participants included 13 women and 13 racially/ethnically minoritized participants; 17 were assistant professors. We enrolled 59 patients: 37 women and 22 men. Most patients were White, non-Latino. Three major themes emerged: physicians with minoritized identities described their social identities differently from physicians with non-minoritized identities; physicians with minoritized identities described professional practices differently from physicians with non-minoritized identities; and physicians’ actions corresponded to their described identities. We provide examples below and in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 25 Participating Faculty Interviewed and Observed, From a Study of Academic Physicians’ Performance of Professional Identity, University of Utah School of Medicine, 2015–2016

| Rank | Minoritized | Non-minoritized | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian American | Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian/American Indiana | Black/African American | White, Latino | Biracial/multiracial/other | White, non-Latino | |

| Women | ||||||

| Fellow | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Instructor | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Assistant professor | 2 | – | 1 | 2 | – | 2 |

| Associate professor | – | – | – | – | 1 | 2 |

| Full professor | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Men | ||||||

| Fellow | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Instructor | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Assistant professor | 1 | – | – | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Associate professor | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Full professor | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Overall totalb | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 12 |

Because there are so few faculty in the sample who identified as Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian/American Indian, we combined this group to maintain anonymity.

Although the sample contained few participants from each racial/ethnic category, the sample was proportionally more diverse than the faculty at our institution. For example, the three Black/African American participants in our sample comprise 12% of the total sample, while Black/African American faculty only make up 0.8% of our institution’s faculty.

Table 2.

Themes that Emerged from Qualitative Analysis of Interviews and Observations on the Subject of Social and Professional Identities, From a Study of 25 Academic Physicians’ Performance of Professional Identity, University of Utah School of Medicine, 2015–2016

| Theme | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Physicians described social identities differently | |

| Women | [Gender] is a big one … it definitely is a big deal to be a woman. |

| My gender is probably my primary [identity]; I identify as female. | |

| I guess I identify kind of on my gender more than anything else. | |

| [with regards to how patients call her by her first name] I think patients, as well as staff, sometimes [do it] too “I’m like you wouldn’t do that to Dr. Smith, for example.” Like my boss who’s a man—you would not come into his office and say “Hey, John…” You just wouldn’t. | |

| I think [gender] does make a difference, and I definitely purposely wear [my white coat] most of the time, but even with that I still get you know I can be wearing my white coat and my stethoscope and ID badge and dressed professionally and still have people say we haven’t seen the doctor all day. | |

| It definitely is a big deal to be a woman…. Even in the field of pediatrics which is the majority female, I still most often when encountering someone who doesn’t know what I do, but who sees me in scrubs or hears that I have worked overnight in the hospital, the most common response is, “Oh are you a nurse?” | |

| Men | I don’t notice [gender] very much frankly. |

| [I am] male, sort of standard male identity. | |

| Racially/ethnically minoritized participants | I think probably for me one of the things I identify most is being a person from South America. |

| I think still being Asian American is my dominant identity. | |

| I think I have a strong connection to Peru as part of my heritage. | |

| So when they come in … sometime I see a blank stare because I’m sure they were looking for an older white male which didn’t happen, and I am not sure they have ever seen a person from [my country], or so. | |

| When you grow up being an ultra minority. It’s nothing you are mad about, you are just different, and everyone knows it. You get comments all the time that remind you of your otherness. | |

| As a woman and a minority, it has its own special set of challenges. You know, your classmates doubting whether you actually really belong, that you didn’t take the spot of a more qualified White male. You know, I had harassment emails when I was in medical school and the Dean’s Office didn’t do anything. | |

| Racially/ethnically non-minoritized participants | I’m very White [laughter]. |

| I’m a … Waspy guy from a pretty Waspy background. | |

| It wasn’t until I was 14 that I knew that I was actually White. And that being Greek-American was more of a cultural thing. | |

| My family is very open and very accepting and so I never felt like there was any sort of bias. But you sometimes don’t realize what biases you have until you’re actually in situations with more diverse people. | |

| I don’t think it was like this totally idealistic like there were no racial issues, [but] … I had never really thought through how one negotiates those different kinds of disparities because it was like never part of my reality in a lot of ways. | |

| Theme 2: Physicians described professional practices differently | |

| Building relationships | |

| Professional learning | [I learned to be a physician from] seeing my dad’s doctors … shadowing, and then observing it in medical school about what it meant to be a physician. |

| There is that traditional boundary thing, but if you bond with someone, that is a natural thing to give someone a hug or if they are crying or if they feel blue, to also comfort them physically and not just give them tissue, so [my mentor] was very much like that. | |

| Personal learning | I think being able to speak Spanish that’s really helpful to a lot of my Spanish speaking patients especially a lot of them are brand new to the U.S. and they get diagnosed with [a disease],… so I think it’s a comforting thing that I can at least communicate with them. |

| I think I’m easily relatable because I think I’ve interests in few places. I like to go fishing, or I like to try to find an interest of theirs, and at least provide some confidence in whether it’s like fishing or being outside. A lot of people like doing things outside around here—cooking, or children, or what have you. Just to kind of humanize the appointment. I think that’s one of my strengths. | |

| Personalized care | |

| Professional learning | I think there needs to be an understanding really between what the patient is expecting and what they want out of their care and what they want out of their treatment, which is going to differ across the spectrum from old to young to cultural upbringings to what expectations doctors can provide to race, ethnicity—whatever … those expectations need to be taken into consideration. |

| I think what you realize is that the same approach doesn’t work for each patient. And so having open-ended questions works for most patients…. There are patients who really want you to direct their care, and then there are many patients that don’t. | |

| Personal learning | Between college and medical school I was an EMT for a year, driving an ambulance. So everybody calls the ambulance, right?… So THAT was really eye-opening, because you’re in people’s houses, right? And you’re seeing what people live like. That was a real eye-opening experience. I think it was kind of a shock…. It made you realize what a lot of people live like … if you don’t understand how people live, it’s hard to understand why they don’t do the things that doctors ask them to do. Like take their medications. Because maybe their home life is really hectic or they can’t afford their medication, even if they’re really cheap. Or why they no-show to their appointments because they can’t afford a car and they can’t make it to their appointments. And busses break down, so it gives you a better reference for understanding the patients and the things that make it hard for them to do what they’re trying to do. |

| Conveying information | |

| Professional learning | Everyone has a different level of understanding and ability with medical jargon or medical information in general and kind of being a steward for that by providing them as much as information that’s fact-based and not based on my personal opinions unless they ask me. |

| Here’s a pattern we default to, where interacting with patients we want to give them as much information as possible. Most of the time it’s too much … so if there are four things I want to communicate with my patient, I start with two. And we go through that and then I try to assess their understanding. And if they get it, and they can communicate it back to me, and we have time then we’ll move on to the next to. And if not, then I say, OK, this is a good place to stop…. So let’s do these things and then come back and visit these other issues in a month. | |

| Personal learning | I think that I have a better appreciation [having taught high school] for meeting people where they are as far as talking to patients. Because I think that there’s a gap between providers and patients and in regards to health literacy, which makes sense because you go to school and you [talk like] this big fancy person. But then you have to tell a real person what is going on and make that real to them, and make them understand it. |

| Theme 3: Comparisons of described practices with patient interactions | |

| Observable matches | Description of practice from interview:

|

Observed patient interaction:

| |

Description of practice from interview:

| |

Observed patient interaction:

| |

Description of practice from interview:

| |

Observed patient interaction:

| |

| Unobservable matches | Description of practice from interview:

|

Description of practice from interview:

| |

Description of practice from interview:

| |

Description of practice from interview:

| |

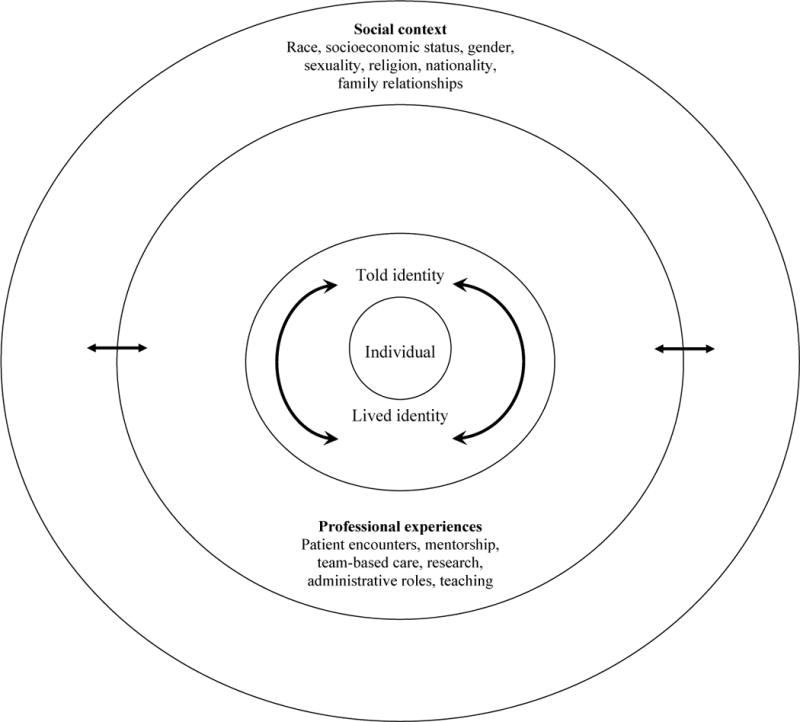

From our exploration, we developed a conceptual model (Figure 1) that illustrates how social and professional contexts interact with one another and how each of these contexts influences an individual’s told and lived identity performances. As the figure illustrates, each individual’s identity is performed as both told and lived expressions. This identity is located within and influenced by professional experiences, which are in turn embedded within and influenced by broader social experiences. These professional and social experiences affect each other and an individual’s identity performances.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model illustrating how identity performance is a cyclical process, which is informed by social contexts and professional experiences. From a study of 25 academic physicians’ performance of professional identity, University of Utah School of Medicine, 2015–2016.

Physicians with minoritized identities described social identities differently from physicians with non-minoritized identities

Beginning with the outer circle in our model, we describe how social experiences affect physicians’ identity performances. A Black/African American female physician (participant 15) noted that even after introducing herself as the physician, “I am often times not automatically perceived as the doctor,” describing how patients often ask, “when is the doctor is coming?” This quote exemplifies how women and racially/ethnically minoritized physicians performed their social identities differently: they described how social identities were defining elements and provided examples of feeling different at work because of these identities. Men and White, non-Latino/a participants did not describe similar instances.

Women said their gender identities were important and even integral to their professional identities. Participant 11 said, “being a female surgeon specifically is one of my key parts of my identity.” At the same time, their authority was doubted because of their gender. Participant 5 remarked, “I think in many cases they’re expecting an older male with a bowtie.”

Contrastingly, several men said they did not think about gender or provided nondescript descriptions of gender identity. Participant 1 said: “[I only think about gender identity] when I check off those boxes.” Others, such as participant 10, said they knew gender differences existed but these differences did not affect them: “ gender doesn’t affect me … but there are lots of studies that say that women are treated differently from men in terms of health disparities.”

Racially/ethnically minoritized physicians recounted how race/ethnicity was a salient identity. Participant 2 noted, “being Asian American in this society … the model minority … it is a double-edged sword.” Racially/ethnically minoritized physicians described instances of being doubted by colleagues. Participant 20, a Black/African American woman, recounts: “There is the side where if you don’t work hard or twice as hard … then you are perceived as lacking.”

Meanwhile, many White, non-Latino/a physicians echoed the sentiment that their race was merely a physical descriptor rather than a cultural experience. Participant 16 said, “I’m very Caucasian. I’m freckled, and I burn very easily, and that’s just what it is.” Others talked about opting in and out of their ethnic identities. Some qualified their Whiteness, such as participant 11 who said, “I don’t feel like I’m a close-minded White person,” and participant 18 who remarked on living in “ethnically and racially diverse” places. Few acknowledged their racial privilege the way participant 23 did: “I’m never going to be a minority in the sense of … a power structure or a power dynamic [because I’m White].”

Physicians with minoritized identities described professional practices differently from physicians with non-minoritized identities

Next, we explore how the middle circle in our model, professional experiences, affects physicians’ identity performances. Participant 22 noted: “I’m trying to move towards less paternalism.… I try to lay out the risk and benefits and then let them choose.” This quotation exemplifies how physicians learn to “be” doctors engaging in clinical practice. Some spoke about care delivery as something they had learned through their professional training, while others spoke about the ways in which their social identities and personal learning informed their care. Participants who shared personal learning experiences often drew from incidents connected to their minoritized identities.

Relationship building

Participants described how important it was to build relationships with patients by listening, making eye contact, validating their concerns, getting to know them beyond their disease, and offering physical comfort. Some participants learned this from mentors. Participant 25 said, “I always sit down with my patients—I learned that from mentors who always sat.… I don’t look at the computer … I just put my hands in my lap and I listen.” Others learned to build relationships from personal experience. Participant 16, a White, non-Latino male physician, explained how his approach is informed by his “blue collar” upbringing. He “rarely wear[s] a white coat” because he “feel[s] like it’s a charade.” Participant 3 noted that relationship building stemmed from a shared gender identity: “I treat almost exclusively women…. I almost always hug my patients … being a woman is an important part of that.”

Personalized care

Participants also discussed learning how to provide personalized treatment. Participant 21 allows patients to text her like her mentor did: “you have to communicate with people how they communicate with their own social circle.” Others explained how personal learning influenced their approaches to personalized care. Participant 10 grew up with “native traditional practices” and engages in personalized treatment by being “supportive” of patients who want to use “alternative medicine” as long as they do not interact with prescribed medications.

Conveying information

Finally, participants spoke at length about conveying information to patients about their disease prognosis, treatment, and follow-up. Participant 8 explained how she learned how to do this from her mentor: “So when I meet a new patient I sit down next to them and I write out their diagnosis, and their treatment—and it’s all just very personal and I learned a lot of that from [my mentor].” Participants also discussed how their personal backgrounds influence how they provide information to patients. A female internist, participant 19 described her “slightly feminist perspective” in prescribing care. She explained to many patients that being an unhappy “stay at home mom … does not make [them] a bad person [but] a human being” before recommending that they find “an activity” to engage in outside of their roles as mothers.

Physicians’ actions (lived performances) correspond to their described actions (told performances)

Finally, connecting the observation findings with the interview findings, we explore the inner circle in our model. We explore how lived and told identities inform and correspond with each other with regards to building relationships with patients, providing personalized care, and conveying information. Unlike in the previous two findings, we did not find that participants’ lived performances differed by their gender or racial/ethnic identities. All participants interacted with patients the way they described. However, although all of the participants’ interactions with patients corresponded to their descriptions of how they related to patients, not all of the descriptions (particularly those related to personal learning around minoritized identities) were observed. We use excerpts from participants’ interactions with their patients to illustrate how they match with self-described practices from the interviews.

Relationship building

Physicians discussed the multiple ways they bonded with patients. A biracial female physician, participant 8, mentioned, “you can’t talk about cancer all the time, so you have to talk about other things.” After greeting one of her patients, she remarked “You’re going to let someone else do Easter this year?” confirming she understood their holiday practices.

Personalized care

Several physicians explained that they try to offer patients options and let them decide on treatment plans when possible. Participant 11, a female physician who is very interested in shared decision making, explained how she offers recommendations but lets patients decide. We observed her saying, “What I would recommend is [this plan] and it sounds like you’re saying that’s what you’ve been thinking anyway. But you can tell me if I’m wrong.”

Conveying information

Finally, physicians expressed interest in providing as much information as possible to patients. Participant 6 noted, “Many times I’m their primary venue to understanding their disease process…. I feel like I spend more time with patients than some of my peers do—both getting to know patients and also explaining what I’m thinking.” The end of this participant’s visit with a patient was spent explaining the biology behind a symptom separate from the patient’s chief complaint.

Discussion

We explored and developed a conceptual model that illustrates how professional identity formation is influenced by social and professional contexts and how these contexts work together to influence one’s identity performances (Figure 1).

Although the demographic composition of U.S. physicians is changing,30 our findings suggest that women physicians and racially/ethnically minoritized physicians still experience personal life and professional life differently. The women performed told identities that enumerated negative professional experiences associated with their gender identities. Similar to recent articles which describe how women are not afforded the same authority as men,17,18 our findings also suggest that women physicians struggle with this bias. The racially/ethnically minoritized physicians also provided examples of facing discrimination, which corroborates previously reported experiences.16,31,32

Men did not convey instances of discrimination, nor did White, non-Latino/a physicians who discussed race differently than racially/ethnically minoritized physicians. Some White, non-Latino/a physicians talked about their racial/ethnic identity within the context of being “open-minded” as an individual, reflecting a perception of Whiteness as linked to an individual’s actions and not to a systemic social structure.19,33 One privilege of being part of the majority (whether with regards to socioeconomic status, ability, religion, sexuality, gender, or race) is not having to think about life from the perspective of the minoritized.19,24

This may help to explain why some participants made explicit connections between their personal learning and their professional practice as physicians and some did not. Physicians’ connections were often based on an aspect of a marginalized identity. For example, participant 3 noted she could connect better with women patients because shared of common experiences based on gender.

Minoritized physician participants have experienced what it is like not to fit into the majority, and these moments of struggle have likely prompted them to reflect on these identities34 and create ways to bridge these struggles and their practice. Our findings suggest that physicians with minoritized identities also make connections between personal experiences and clinical practice. Case and Brauner3 suggest that performance studies is key to helping future physicians develop empathetic imaginations: “a cognitive skill set that helps one to imagine the experiences and responses of another person.” Thus, it seems that physicians’ identity struggles might lay the groundwork for them to empathetically imagine patients’ perspectives.

Lastly, the observational data confirmed that the participants’ told identities matched their lived identities, although not all aspects of the told identities were observable. For example, while we saw evidence that physicians do engage in relationship building, personalization, and conveying information, we did not always observe physicians making efforts to build the cross-cultural relationships they spoke about in Table 2 (e.g., speaking Spanish with a patient). We conjecture that this is because all high-quality patient interactions involve elements of relationship building, personalization, and conveying information, but not all interactions involve high levels of racial/ethnic cultural inclusivity, particularly in our study setting, where the majority of patients are White, non-Latino/a. Thus, the patients may not have performed in ways to elicit the more nuanced care that some of the physicians spoke about.

Implications

Our findings correspond to theoretical models of professional identity formation, which posit that physicians with minoritized identities have more to negotiate in integrating their social and professional identities, but also suggest that while minoritized identity experiences can result in discrimination, they can also be an asset that provides grounds for connecting with patients.35 Our analysis also suggests that physicians make connections with patients from similar backgrounds. Because the patient population is diversifying at a faster rate than the physician population,30 it is imperative that all physicians, both minoritized and non-minoritized, be prepared to interact with minoritized patients. Therefore, students and trainees would benefit from reflecting on how their personal identities inform their professional identities and practices. In addition, our study suggests that practicing physicians, particularly those who do not train in diverse settings, could also benefit from professional learning opportunities that encourage reflection. Such reflection by students, trainees, and practicing physicians could also lead to an understanding of why healthcare inequalities continue to exist.

All physicians would benefit from explicit opportunities to reflect on life experiences and how to connect these experiences to clinical practice. While reflective practice is already a component of the curriculum,36 its overuse has resulted in “reflection fatigue.”37 Thus, the reflection we encourage incorporating must be purposeful and tied to existing practices as often as possible, such as using morbidity and mortality conferences as opportunities to reflect on medical procedures as well as on personal growth and development.

Limitations and future research

Our study has limitations. The exploratory context of 25 physicians from a single institution who self-selected into our study limits generalizability of our findings. We had more assistant professors than associate or full, and being newer to the profession could have influenced respondents’ experiences. Also, using data from one interview and two observations with each physician in all likelihood did not allow us to fully capture the dynamic nature of identity performance. In addition, recruiting patients through physician participants rather than by random assignment and having the researcher present during the interaction could have influenced observation data. Finally, we acknowledge that we bring our own lenses to this work, which can influence our interpretation of the data. The rigor of this investigation was enhanced by multiple techniques, including immersion in the data, adequate sample size, peer debriefing, and maintenance of an audit log.

Considerations for future research include conducting this study with more participants and at different institutions, using the concepts from this study to develop and conduct a survey with a larger and perhaps more representative sample, and exploring how identities are performed across different medical specialties. An additional direction is the investigation of how identity performance functions in team-based care settings where medical assistants, nurses, physician trainees, and practicing physicians each have to negotiate personal and professional identities to work with each other. Furthermore, although we originally thought that religious identity might emerge as a prominent influence in professional practice given our setting and the prominence of the Mormon faith, it did not, but this could be an additional future line of inquiry.

Conclusion

This research suggests that physicians with gender and racially/ethnically minoritized identities perform identities differently than physicians with non-minoritized identities. Findings also suggest that physicians’ social identities influence their professional practice. Finally, our findings imply that physicians’ told performances match their lived performances, though our data did not provide a complete picture of all lived performances. This exploratory study provides an additional perspective on how the integration of reflection and acknowledgement of social and structural power systems into medical education can prepare future and current physicians to be more aware of how they perform their physician identities.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Gretchen A. Case, Boyd Richards, and Susan Zickmund for providing critical feedback during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors also wish to thank the participants for sharing their stories.

Funding/Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR001067, the University of Utah H.A. and Edna Benning Presidential Endowment, the University of Utah Office of Health Equity and Inclusion Student Research Stipend.

Appendix 1 Interview Guide/Protocol, From a Study of 25 Academic Physicians and Performance of Professional Identity, University of Utah School of Medicine, 2015–2016

Note: These questions are only meant to serve as a guide. Interviewer will use these questions as prompts to open up conversation and will follow up on what participants say as needed.

Introduction

Can you tell me about your background (prompt for childhood/personal background as well as training)?

How did you decide to become a physician?

How did you decide on your specialty?

How long have you been a physician?

How do you decide on your research projects/topics?

Tell me about your daily routines/responsibilities.

Identity and practice

-

What does it mean to be a physician? How did you arrive at this understanding (has it evolved over time)?

Are there certain ways people think of physicians? How do you think this affects how people see you?

-

What do you think are the most important parts of your identity (prompt with identity descriptors, e.g., race, socioeconomic status, religion, etc., if needed)?

How did you arrive at this understanding of your identity?

What identities are important to you as you practice medicine?

-

Do you think your identities shape how your supervisors, colleagues, trainees, patients see you? If so, how?

How have your identities influenced how your impact on patients?

-

What is patient-centered care?

How do your own identities or experience influence this definition and your practice of patient-centered care?

-

Who is your most memorable mentor? Why? What did you learn from them? What do you do based on how they mentored you?

Did their mentoring affect how you see yourself?

-

Are there things you do differently from your colleagues?

If so, what/how?

Are there things you do differently with research patients/participants than with clinic patients?

Wrap-Up

What advice do you have for medical students or trainees regarding how to incorporate their identities into their work?

Is there anything else you’d like me to ask that I didn’t bring up?

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This study was reviewed by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board on September, 28, 2015, and given approval reference IRB_0008633. Expedited continuing reviews for this study were subsequently approved on September 27, 2016, and on August 25, 2017.

Previous presentations: This work was partially presented at the Association for Clinical and Translational Science (ACTS) conference, Washington, D.C., April 20, 2017; and at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Learn Serve Lead conference Boston, Massachusetts, November 4, 2017.

Contributor Information

Candace J. Chow, Research associate, Utah Education Policy Center, University of Utah College of Education, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Carrie L. Byington, Jean and Thomas McMullin Professor and dean of Medicine, senior vice president, Health Science Center, and vice chancellor for health services, Texas A&M University, Bryan, Texas.

Lenora M. Olson, Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Karl Paulo Garcia Ramirez, Research assistant and graduate of the College of Health, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Shiya Zeng, Undergraduate student and research assistant, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Ana María López, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine; associate director, Collaboration and Engagement, Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science; and associate vice president for Health Equity and Inclusion, University of Utah Health Sciences, Salt Lake City, Utah.

References

- 1.Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New York: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; 1910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaufberg EH, Batalden M, Sands R, Bell SK. The hidden curriculum: What can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med. 2010;85:1709–1716. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f57899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Case GA, Brauner DJ. Perspective: The doctor as performer: A proposal for change based on a performance studies paradigm. Acad Med. 2010;85:159–163. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c427eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: Integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87:1185–1190. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182604968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frost HD, Regehr G. “I am a doctor”: Negotiating the discourses of standardization and diversity in professional identity construction. Acad Med. 2013;88:1570–1577. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a34b05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke M, Irby D, O’Brien B. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cope A, Bezemer J, Mavroveli S, Kneebone R. What attitudes and values are incorporated into self as part of professional identity construction when becoming a surgeon? Acad Med. 2017;92:544–549. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: A guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90:718–725. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wald HS. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: Reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med. 2015;90:701–706. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: Considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012;34:e641–e648. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller’s pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2016;91:180–185. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89:1446–1451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: Why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44:40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller E, Balmer D, Hermann N, Graham G, Charon R. Sounding narrative medicine: Studying students’ professional identity development at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Acad Med. 2014;89:335–342. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong A, Trollope-Kumar K. Reflections: An inquiry into medical students’ professional identity formation. Med Educ. 2014;48:489–501. doi: 10.1111/medu.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montenegro RE. A piece of my mind. My name is not “Interpreter”. JAMA. 2016;315:2071–2072. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pingleton SK, Jones EVM, Rosolowski TA, Zimmerman MK. Silent bias: Challenges, obstacles, and strategies for leadership development in academic medicine—Lessons from oral histories of women professors at the University of Kansas. Acad Med. 2016;91:1151–1157. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, et al. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1033–1036. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson AG. Privilege, Power, and Difference. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, Ca: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methdology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report. 2008;13:544–559. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byington CL, Keenan H, Phillips JD, et al. A matrix mentoring model that effectively supports clinical and translational scientists and increases inclusion in biomedical research: Lessons from the University of Utah. Acad Med. 2016;91:497–502. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiAngelo RJ. What does it mean to be white? Developing white racial literacy. New York, NY: Peter Lang; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989:139–168. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow CJ. Teaching for social justice: (Post-)model minority moments. Journal of Southeast Asian American Education and Advancement. 2017;2 article 3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall C, Rossman GB. Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the Physician Workforce: Facts & Figures. 2014 aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/. Accessed April 30, 2018.

- 31.Herreria C. Physician says racist “white doctor” rant reflects larger issue in Canada. Huffington Post. 2017 Jun 22; https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/physician-reacts-white-doctor-canada_us_594b1f7ee4b01cdedf00448f. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- 32.Emery CR. Against all odds: Celebrating black women in medicine. West Haven, CT: URU, The Right To Be, Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matias CE. Feeling white: Whiteness, emotionality, and education. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hooks B. Choosing the margin as a space of radical openness. In: Garry A, Pearsall M, editors. Women, Knowledge, and Reality: Exploration in Feminist Philosophy. New York: Routledge; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou SY. Underprivilege as privilege. JAMA. 2017;318:705–706. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31:685–695. doi: 10.1080/01421590903050374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trumbo SP. Reflection fatigue among medical students. Acad Med. 2017;92:433–434. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]