Abstract

Background

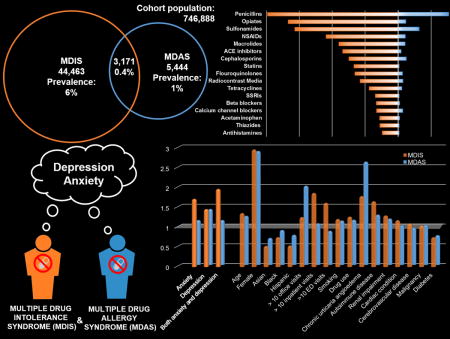

The epidemiology of Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome (MDIS) and Multiple Drug Allergy Syndrome (MDAS) are poorly characterized. We used electronic health record (EHR) data to describe prevalences of MDIS and MDAS and to examine associations with anxiety and depression.

Methods

Patients with ≥3 outpatient encounters at Partners HealthCare System from 2008–2015 were included. MDIS patients had intolerances to ≥3 drug classes and MDAS patients had hypersensitivities to ≥2 drug classes. Psychiatric conditions and comorbidities were defined from the EHR, and used in multivariable logistic regression models to assess the relation between anxiety/depression and MDIS/MDAS.

Results

Of 746,888 patients, 47,634 (6.4%) had MDIS and 8,615 (1.2%) had MDAS; 3,171 (0.4%) had both. Anxiety (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.72 [1.65, 1.80]), depression (aOR 1.46 [1.41, 1.52]), and both anxiety and depression (aOR 1.97 [1.86, 2.08]) were associated with increased odds of MDIS. Depression was associated with increased odds of MDAS (aOR 1.41 [1.28, 1.56]), but there were no clear associations with anxiety (aOR 1.13 [0.99, 1.30]) nor both depression and anxiety (aOR 1.13 [0.92, 1.38]).

Conclusion

While 6% of patients had MDIS, only 1% had MDAS. MDIS was associated with both anxiety and depression; patients with both anxiety and depression had an almost 2-fold increased odds of MDIS. MDAS was associated with a 40% increased odds of depression, but there was no significant association with anxiety. Psychological assessments may be useful in the evaluation and treatment of patients with MDIS and MDAS; physiologic causes for MDAS warrant further investigation.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, healthcare utilization, hypersensitivity, immunologic

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Drug allergies are commonly reported by patients and documented in medical charts (1–5). Patients reporting any drug allergy history are likely to report allergies to multiple drug classes (2, 6). Drug allergies documented in the electronic health record (EHR) can be intolerances, toxicities, or hypersensitivities (i.e., immunologic reactions) (7). While definitions have varied (2, 8–10), Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome (MDIS) describes patients who have non-immunologic reactions to three or more drug classes (2, 11), and Multiple Drug Allergy Syndrome (MDAS) describes patients with hypersensitivity reactions to two or more drug classes (12–15). A third term, Multiple Drug Hypersensitivity (MDH) describes patients with proven hypersensitivities to two or more distinct drugs after drug allergy evaluation (9).

MDIS occurs in about 2% of patients (2, 11). While the prevalence of MDAS remains unknown, at least 5% of patients report one or more drug hypersensitivity (1, 2, 16, 17), and at least 10% of those patients (or 0.5% of patients) have MDAS (6, 18). Commonly described drug culprits in both MDIS and MDAS include antibiotics, antiepileptics, hypnotics, antidepressants, local anesthetics, glucocorticoids, opiates, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (10, 11, 19, 20). Urticaria and angioedema are the most commonly described reactions in MDAS, although severe reactions (e.g., bullous exanthema, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug rash eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome) have also been described in MDAS (5, 6, 9, 10, 19).

Risk factors for MDIS include female sex, older age, greater weight, prior hospitalizations, and multiple medical comorbidities (2, 11). Female sex has also been identified as a risk factor for MDAS (19, 21, 22). Prior studies have suggested associations between MDIS and/or MDAS and various psychiatric comorbidities, including anxiety, depression, alexithymia, and somatization (22–24). However, to date, no clear relationship is defined.

In this study, we used longitudinal EHR data to describe the epidemiology of reported MDIS and MDAS in a large United States healthcare system, and evaluated the relationship between anxiety, depression, MDIS, and MDAS.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective study of patients seen at Partners HealthCare System (PHS), an integrated health care delivery network in the Boston area, from January 1, 2008 through May 31, 2015. To improve cohort continuity, the study population included patients with at least one outpatient visit prior to 2008 and three or more visits from 2008 through 2015. Patients’ allergy information was obtained from the Partners Enterprise Allergy Repository (PEAR) (1, 16, 25, 26), which is a large electronic allergy database containing patients’ longitudinal allergy histories from EHR allergy lists across PHS network sites. Allergies included in PEAR are observed by clinicians and/or reported by patients. PEAR data include a list of ‘allergens’ (i.e. drug, drug class, food), allergy status (active or inactive/deleted), date/time allergy entered or updated, and reaction(s). Recurrences to the same drug cannot be determined from these data; however, recurrences attributed to different drugs or drug classes would exist as separate PEAR entries.

MDIS and MDAS

MDIS patients had intolerance or side effect reactions to three or more drug classes; MDAS patients had reactions to two or more drug classes with a possible immunologic mechanism. To identify reactions with a possible immunologic mechanism (i.e., hypersensitivity reactions [HSRs]), we used both coded and free text (non-coded) reaction entries in PEAR and keyword searches (Supplemental Table 1). We considered reactions that mapped to hypotension, shock, arrest, and arrhythmia with anaphylaxis. Bronchospasm, wheezing, and asthma were considered with shortness of breath. All entries of “rash” without further description were assumed to be delayed-type eruptions/type IV HSRs. To categorize drug allergens, we performed drug and drug class keywords searches, similarly using coded and free text data (1–3, 11). We used an iterative semi-automated methodology, which involved manual review and validation of groupings until >90% of MDAS allergens were classified.

MDIS and MDAS were defined at the end of the study period (i.e., 2015), but also evaluated at the beginning of the study period (i.e., 2008) in sensitivity analyses, since the timing of reactions is unknown for PEAR entries and entries can be added and removed over time (27). Because of varied literature definitions of MDIS and MDAS (Supplemental Table 2) (2, 15, 28, 29), we also evaluated alternative definitions of MDIS (two of more drug class intolerances) and MDAS (three of more drug class hypersensitivities) in sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of Variables

The primary variables of interest were anxiety and depression. Anxiety was defined by patients who had a relevant International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition (ICD-9) code and a prescription of anxiolytic medication within one year of that code from 2008 through 2015 (Supplemental Table 3). Depression was similarly defined by ICD-9 codes and an antidepressant prescription. Because many patients with mild anxiety and/or depression do not receive pharmacologic treatment (30, 31), we also assessed alternative definitions of anxiety and depression that required only an ICD-9 code in sensitivity analyses. As anxiety and depression often coexist (32), we assessed anxiety and depression in four distinct groups: Anxiety only, depression only, both anxiety and depression, and neither anxiety nor depression.

Other variables of interest included age (at study onset), sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status, defined from EHR demographic tables. Smoking, alcohol use, and drug use were defined by the presence of a relevant ICD-9 code or documentation of use in the EHR preventative health information. Individual medical comorbidities (e.g., chronic urticaria angioedema, autoimmune diseases) and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) were defined using ICD-9 codes. All ICD-9 codes were informed by prior studies, when available (Supplemental Table 3). Allergies to vaccines, foods and environmental allergens were defined from PEAR. Healthcare utilization was identified from EHR encounter tables, and considered as another proxy for overall health and degree of exposure to medications.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated the prevalences of MDIS and MDAS. For all patients who met MDIS and/or MDAS definitions, we calculated drug/drug class frequencies. For all MDAS patients, frequencies of HSRs by name and type were calculated.

We identified patients with MDIS only, MDAS only, both MDAS and MDIS, and neither MDAS nor MDIS. For risk factor analysis, patients with neither MDIS nor MDAS served as the comparator group (i.e., controls); patients with both MDAS and MDIS were excluded from association analyses to improve discrimination of MDAS and MDIS patient groups.

We compared characteristics between patients with MDIS only, MDAS only, and controls in unadjusted analyses. We used logistic regression models to evaluate independent associations for MDIS and MDAS. In the primary model, we included all variables, except those related to MDIS/MDAS (e.g., vaccine allergy, food allergy). To determine the stability of our conclusions, we conducted various sensitivity analyses around the definitions of the psychiatric conditions and MDIS/MDAS, and models with different covariates.

We used a stratified analysis to investigate whether the effect of anxiety and depression on drug class intolerances/hypersensitivities increased with the number of drug class intolerances/hypersensitivities. We compared groups of patients with a specific number of drug class intolerances and hypersensitivities to the common control group using separate logistic regression models.

All P values were 2-sided. While P<0.05 was considered statistically significant, we only highlighted clinically important effects due to the large cohort size. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Prevalence, Drugs, and Reactions

Among 746,888 PHS patients meeting visit criteria, 44,463 had MDIS only, 5,444 had MDAS only; 3,171 (0.42%) had both MDIS and MDAS, and 693,810 (92.9%) had neither MDIS not MDAS. The overall prevalence rate was 6.4% (N=47,634) for MDIS and 1.2% (N=8,615) for MDAS.

MDIS patients had reactions to a total of 194,101 culprit drugs (4.1±1.7 per patient). MDAS patients had reactions to 20,307 culprit drugs (2.4±0.8 per patient, Supplemental Table 4). The most common causative drugs were similar for MDIS and MDAS, and included penicillins, opiates, sulfonamides, NSAIDs, cephalosporins, macrolide antibiotics, and radiocontrast media (Table 1). Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors were among the most common drug classes causing reactions in MDIS patients, but not MDAS patients; calcium channel blockers and quinolone antibiotics were among the most common drug classes causing reactions in MDAS patients, but not MDIS patients.

Table 1.

Common drug and drug class intolerances and hypersensitivities in Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome (MDIS) and Multiple Drug Allergy Syndrome (MDAS)

| MDIS* | |

|---|---|

| Penicillins | 19,856 (41.7) |

| Opiates | 16,716 (35.1) |

| Sulfonamides | 15,684 (32.9) |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | 10,926 (22.9) |

| Macrolides | 8,997 (18.9) |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 8,404 (17.6) |

| Cephalosporins | 7,450 (15.6) |

| 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors | 6,714 (14.1) |

| Flouroquinolones | 6,569 (13.8) |

| Radiocontrast media | 5,769 (12.1) |

|

| |

| MDAS† | |

|

| |

| Penicillins | 4,384 (50.9) |

| Sulfonamides | 3,190 (37.0) |

| Cephalosporins | 1,209 (14.0) |

| Opiates | 1,137 (13.2) |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs | 1,071 (12.4) |

| Macrolides | 1,051 (12.2) |

| Radiocontrast media | 730 (8.5) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 680 (7.9) |

| Flouroquinolones | 660 (7.7) |

| Tetracyclines | 536 (6.2) |

47,634 MDIS patients had a total of 194,101 culprit drugs.

8,615 MDAS patients had a total of 20,307 culprit drugs.

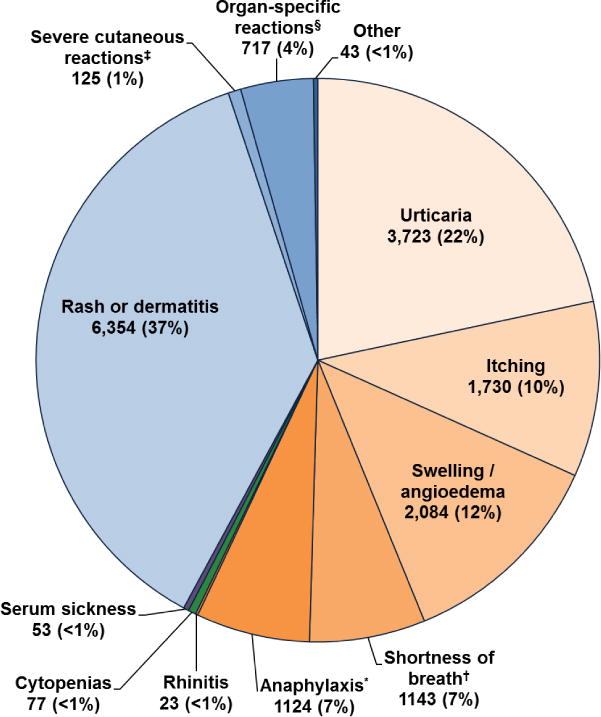

MDAS patients reported 17,196 reactions suggestive of Type I HSRs, including urticaria (21.7% of reactions in 43.2% of MDAS patients), itching (10.1% of reactions in 20.1% of MDAS patients), angioedema/swelling (12.1% of reactions in 24.2% of MDAS patients), shortness of breath (6.7% of reactions in 13.3% of MDAS patients), anaphylaxis (6.5% of reactions in 13.0% of MDAS patients), and rhinitis (0.1% of reactions in 0.3% of MDAS patients, Figure 1). Type II and III HSRs were infrequently identified, but included cytopenias (0.4% of reactions in 0.9% of MDAS patients) and serum sickness like reactions (0.3% of reactions in 0.6% of MDAS patients). Type IV HSRs were common, and included rash or dermatitis (37.0% of reactions in 73.8% of MDAS patients), organ-specific reactions (4.2% of reactions in 8.3% of MDAS patients), severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs, 0.7% of reactions in 1.5% of MDAS patients), and fixed drug eruptions (0.03% of reactions in 0.1% of MDAS patients). Organ-specific reactions were largely acute interstitial nephritis cases (n=667, 3.9% of reactions in 7.7% of MDAS patients). SCARs were Stevens-Johnson syndrome (n=60), exfoliative dermatitis (n=24), drug rash eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome (n=17), erythema multiforme major (n=14) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (n=10).

Figure 1.

Hypersensitivity reactions identified in MDAS patients.

17,196 hypersensitivity reactions were identified among 8,615 MDAS patients. Other includes drug induced lupus (n=14), erythema nodosum (n=14), eosinophilia (n=10), and fixed drug eruption (n=5).

*Anaphylaxis was defined by the symptoms of hypotension, shock, arrest and arrhythmia.

† Shortness of breath was defined by the symptoms of bronchospasm, wheezing, and/or asthma.

‡ Severe cutaneous reactions included Stevens-Johnson syndrome (n=60), erythema multiforme (n=14), toxic epidermal necrolysis (n=10), drug rash eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (n=17), and exfoliative dermatitis (n=24).

§ Organ-specific reactions include acute interstitial nephritis (n=667), immune-mediated hepatitis (n=39), aseptic meningitis (n=6), and interstitial pneumonitis (n=5).

Cohort Characteristics

MDIS only and MDAS only patients were older, and more commonly female and white, compared to patients with neither MDIS not MDAS (comparator patients, Table 2). Marital status differed between patient groups, with married and single being most frequent in the MDAS patients, and widowed being most frequent in comparator patients. Smoking was most common in MDIS and least common in comparator patients. Alcohol use and drug use were infrequently identified overall, but most frequent in MDIS patients compared to MDAS patients and comparators. Other allergies were more common in MDIS and MDAS patients than comparators. Chronic urticaria/angioedema was most common in MDAS, compared to MDIS and comparators. All other medical comorbidities were most prevalent in MDIS. CCI was similar in MDIS and MDAS, and higher than in the comparators patients. MDAS patients had frequent outpatient healthcare utilization; MDIS patients had the most frequent inpatient and emergency room visits.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome (MDIS) and Multiple Drug Allergy Syndrome (MDAS)

| MDIS* n= 44,463 |

MDAS* n=5,444 |

Comparators† n=693,810 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median [IQR] | 57.0 [45.0, 68.0] | 52.0 [41.0, 63.0] | 43.0 [25.0, 58.0] |

| Female sex | 35,642 (80.2) | 4,378 (80.4) | 402,244 (58.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 38,024 (85.5) | 4,513 (82.9) | 530,094 (76.4) |

| Black | 1,993 (4.5) | 285 (5.2) | 38,654 (5.6) |

| Asian | 613 (1.4) | 114 (2.1) | 22,305 (3.2) |

| Hispanic | 763 (1.7) | 149 (2.7) | 24,981 (3.6) |

| Other or Unknown | 3,070 (6.9) | 383 (7.0) | 77,776 (11.2) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 21,496 (48.3) | 2,879 (52.9) | 30,6374 (44.2) |

| Single | 4,105 (9.2) | 1,412 (25.9) | 37,522 (5.4) |

| Divorced or Separated | 4,281 (9.6) | 460 (8.4) | 25,087 (3.6) |

| Widowed | 10,965 (24.7) | 336 (6.2) | 262,617 (37.9) |

| Other or Unknown | 3,616 (8.1) | 357 (6.6) | 62,210 (9.0) |

| Habits | |||

| Smoking | 12,736 (28.6) | 1,387 (25.5) | 117,022 (16.9) |

| Alcohol use | 740 (1.7) | 68 (1.2) | 8,061 (1.2) |

| Drug use | 752 (1.7) | 65 (1.2) | 8,084 (1.2) |

| Other allergies | |||

| Atopic disease | 10,629 (23.9) | 1,250 (23.0) | 115,536 (16.7) |

| Vaccine allergy | 648 (1.5) | 57 (1.0) | 2,774 (0.4) |

| Food allergy | 6,071 (13.7) | 607 (11.1) | 42,952 (6.2) |

| Environmental allergy | 11,283 (25.4) | 1,135 (20.8) | 79,607 (11.5) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Chronic urticaria/Angioedema | 371 (0.8) | 71 (1.3) | 3,323 (0.5) |

| Autoimmune disease | 13,704 (30.8) | 1,178 (21.6) | 131,161 (18.9) |

| Renal impairment | 3,189 (7.2) | 219 (4.0) | 16,042 (2.3) |

| Cardiac disease | 9,871 (22.2) | 779 (14.3) | 86,902 (12.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3,823 (8.6) | 278 (5.1) | 30,500 (4.4) |

| Malignancy | 13,957 (31.4) | 1,433 (26.3) | 147,899 (21.3) |

| Diabetes | 10,567 (23.8) | 868 (15.9) | 105,917 (15.3) |

| Charlson comorbidity index median [IQR] | 3.0 [2.0, 5.0] | 3.0 [1.0, 4.0] | 2.0 [0.0, 3.0] |

| Clinic visits | |||

| 0 visits | 7,110 (16.0) | 770 (14.1) | 178,961 (25.8) |

| 1-5 visits | 6,111 (13.7) | 550 (10.1) | 124,393 (17.9) |

| 6-10 visits | 3,565 (8.0) | 428 (7.9) | 66,054 (9.5) |

| More than 10 visits | 27,677 (62.2) | 3,696 (67.9) | 324,402 (46.8) |

| Hospitalizations | |||

| 0 visits | 26,287 (59.1) | 3,803 (69.9) | 543,991 (78.4) |

| 1-5 visits | 7,306 (16.4) | 846 (15.5) | 83,143 (12.0) |

| 6-10 visits | 3450 (7.8) | 306 (5.6) | 28,072 (4.0) |

| More than 10 visits | 7420 (16.7) | 489 (9.0) | 38,604 (5.6) |

| Outpatient emergency room visits | |||

| 0 visits | 29,896 (67.2) | 4,140 (76.0) | 546,982 (78.8) |

| 1-5 visits | 10,427 (23.5) | 1,054 (19.4) | 120,374 (17.3) |

| 6-10 visits | 2,339 (5.3) | 165 (3.0) | 17,292 (2.5) |

| More than 10 visits | 1,801 (4.1) | 85 (1.6) | 9,162 (1.3) |

MDAS patients have only MDAS and MDIS patients have only MDIS. The 3,171 patients with both MDIS and MDAS were excluded from risk factor analyses (see methods).

No MDAS or MDIS (see methods).

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range

Anxiety and Depression

In unadjusted analyses, patients with psychiatric comorbidities had increased odds of MDIS: Anxiety only (odds ratio [OR] 2.12 [95% CI 2.04, 2.21]), depression only (OR 2.14 [95% CI 2.07, 2.22]), and both anxiety and depression (OR 2.72 [95% CI 2.58, 2.87], Table 3). Similarly, patients with psychiatric comorbidities had increased odds of MDAS: anxiety only (OR 1.30 [95% CI 1.13, 1.49]), depression only (OR 1.82 [95% CI 1.65, 2.00]), and both depression and anxiety (OR 1.32 [95% CI 1.08, 1.60]).

Table 3.

Unadjusted association of anxiety and depression with Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome (MDIS) and Multiple Drug Allergy Syndrome (MDAS).

| MDIS* (n=44,463) | MDAS*(n=5,444) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | OR [95% CI]† | p-value | n (%) | OR [95% CI]† | p-value | |

| Anxiety | 2,685 (6.0) | 2.12 [2.04, 2.21] | <0.001 | 213 (3.9) | 1.30 [1.13, 1.49] | <0.001 |

| Depression | 4,245 (9.6) | 2.14 [2.07, 2.22] | <0.001 | 467 (8.6) | 1.82 [1.65, 2.00] | <0.001 |

| Both anxiety and depression | 1,595 (3.6) | 2.72 [2.58, 2.87] | <0.001 | 100 (1.8) | 1.32 [1.08, 1.60] | 0.007 |

| Neither | 35,938 (80.8) | ref | 4,664 (85.7) | ref | ||

MDIS patients have only MDIS and MDAS patients have only MDAS. The 3,171 patients with both MDIS and MDAS were excluded from risk factor analyses (see methods).

Compared to comparator patients without MDIS or MDAS (n=693,810, see methods), of whom 4.7% have anxiety, 6.5% have depression, 1.5% have both anxiety and depression, and 90.4% have neither anxiety nor depression.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference

In the multivariable model, anxiety (OR 1.72 [95% CI 1.65, 1.80]), depression (1.46 [95%CI 1.41, 1.52]), and both anxiety and depression (OR 1.97 [95% CI 1.86, 2.08]) were associated with MDIS. For MDAS, depression showed a significant association (OR 1.41 [95% CI 1.28, 1.56]), but not anxiety only (OR 1.13 [95% CI 0.99, 1.30]) nor both anxiety and depression (OR 1.13 [95% CI 0.92, 1.38]).

In sensitivity analyses, anxiety was consistently associated with MDIS under varied definitions of the psychiatric disorders and MDIS, and variations in covariates included in the regression model (Supplemental Table 5). For MDIS, ORs for anxiety ranged from 1.41 to 1.72 under different assumptions. Depression only was also consistently associated with increased odds of MDIS, with an OR from 1.38 to 1.46 in sensitivity analyses. Having both anxiety and depression was most strongly associated with MDIS, with an OR ranging from 1.45 to 1.97.

The association between anxiety and MDAS was inconsistent (Supplemental Table 5). The OR ranged from 1.08 to 1.26, without statistical significance in all but two analyses. Depression was consistently associated with MDAS across all sensitivity analyses with OR ranging from 1.26 to 1.44. Having both anxiety and depression was not significantly associated with increased odds of MDAS across sensitivity analyses.

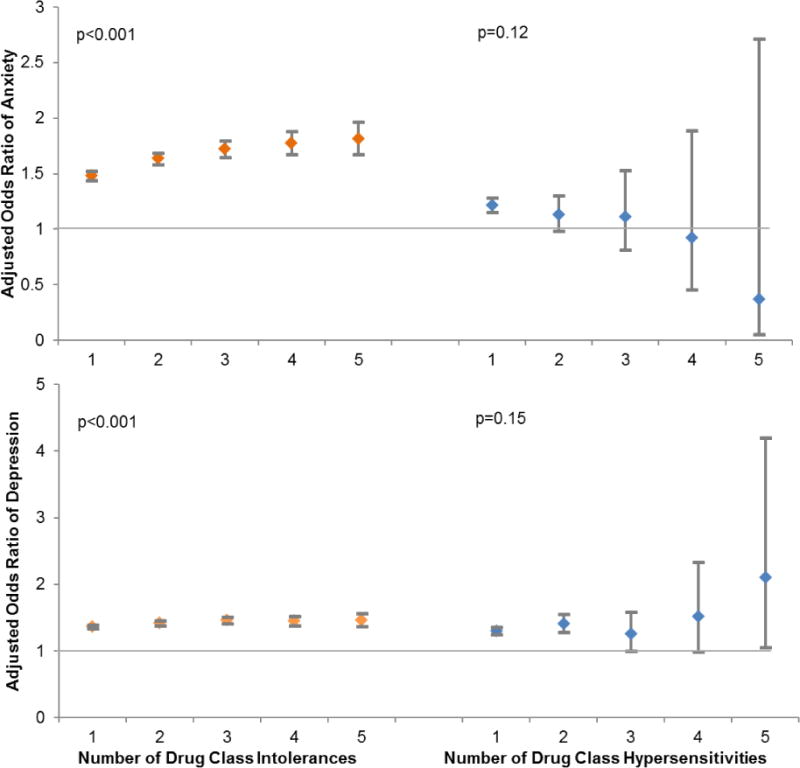

The magnitude of the OR for anxiety was greater with the number of drug class intolerances reported (p for trend<0.001, Figure 2). For patients with one drug class intolerance, odds ratio of anxiety was 1.48; for patients with two drug class intolerances, odds ratio of anxiety was 1.64; for patients with three drug class intolerances, odds ratio of anxiety was 1.72; for patients with four drug class intolerances, odds ratio of anxiety was 1.77; and for patients with five drug class intolerances, odds ratio of anxiety was 1.81. There was no significant relationship between number of drug class hypersensitivities and anxiety (p for trend=0.12).

Figure 2.

Association between number of drug class intolerances and number of drug class hypersensitivities and anxiety and depression.

This figure displays the odds ratio for anxiety (and depression) according to the number of drug class intolerances (or hypersensitivities) documented in the electronic health record. MDIS patients included all patients with 3 or more drug class intolerances and MDAS included all patients with 2 or more drug class hypersensitivities. A significant trend was observed for intolerances: Patients reporting more drug class intolerances had higher odds of anxiety and depression. There was no appreciable trend for hypersensitivities.

The magnitude of the OR for depression was greater with the number of drug class intolerances reported (p for trend <0.001, Figure 2). For patients with one drug class intolerance, odds ratio of depression was 1.36; for patients with two drug class intolerances, odds ratio of depression was 1.42; for patients with three drug class intolerances, odds ratio of depression was 1.46; for patients with four drug class intolerances, odds ratio of depression was 1.45; and for patients with five drug class intolerances, odds ratio of depression was 1.46. There was no significant linear relationship between the effect of anxiety and number of drug class hypersensitivities (p for trend=0.15).

Association with Other Variables

Older age was associated with both MDIS and MDAS; each decade increased odds of MDIS by 36% (OR 1.36 [95% CI 1.36, 1.37]) and MDAS by 24% (OR 1.24 [95% CI 1.22, 1.26]). Female sex was associated with both MDIS (OR 2.97 [95% CI 2.89, 3.04]) and MDAS (OR 2.88 [95% CI 2.69, 3.08]). White race was associated with increased odds of MDIS and MDAS. Having more than 10 office visits (compared to none) was associated with MDIS (OR 1.26 [95% CI 1.22, 1.30]) and MDAS (OR 2.00 [95% CI 1.84, 2.18]). Hospitalizations were also associated with MDIS, with an increased odds of MDIS for patients with 1–5 hospitalizations (OR1.29 [95% CI 1.25, 1.33]), 6-10 hospitalizations (OR 1.52 [95% CI 1.46, 1.58]), and more than 10 hospitalizations (OR 1.87 [95% CI 1.81, 1.94]). Emergency room visits were also associated with MDIS, but not MDAS, especially for patients with more than 10 visits (OR 1.62 [95% CI 1.53, 1.73]). Chronic urticaria was associated most strongly with MDAS (OR 2.61 [95% CI 2.05, 3.31]), but was also associated with MDIS (OR 1.79 [95% CI 1.60, 2.01]). Autoimmune disease was associated with both MDIS (OR 1.66 [95%CI 1.59, 1.73]) and MDAS (OR 1.27 [95% CI 1.13, 1.42]).

DISCUSSION

In this large retrospective study of patients in an integrated US healthcare system, 6% of the population had documented MDIS and 1% had documented MDAS; <0.5% had both MDIS and MDAS documented. While anxiety and depression were associated with MDIS, depression, but not anxiety, was associated with MDAS. The odds of anxiety and depression increased with the number of drug class intolerances patients had, but no similar relationship between number of drug class hypersensitivities and anxiety was identified. Both MDIS and MDAS were associated with older age, female sex, white race, increased healthcare utilization, chronic urticaria, and autoimmune disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first large data report that distinguished MDIS from MDAS using reported reactions, and the first prevalence estimate of MDAS, using EHR data (1%) (8, 9). While we found that 6% of patients had MDIS, prior studies identified prevalences of 2% among patients generally, and 5% among hospitalized patients reporting any medication intolerance (2, 11). Clarification and accurate documentation of drugs and reactions into the EHR allergy list is important for the delivery of medical care for all patients, but especially those with MDIS and MDAS. While clarification of reported hypersensitivities is within the scope of practice for Allergy/Immunology specialists (7, 19, 33, 34), the volume of MDAS patients identified in this study (almost 9,000 PHS MDAS patients) would far exceed the clinical capacity of PHS Allergy/Immunology specialists available to complete such evaluations. Thus, while Allergy/Immunology specialist referral is required for drug allergy testing, any widespread effort to improve allergy documentation in MDIS and MDAS patients will require engagement by non-allergist providers.

Despite using new EHR and informatics methods to define our MDIS and MDAS cohorts, the most commonly identified culprit drugs in this study were similar to the drugs generally reported as allergies and intolerances (i.e., antibiotics, opiates, NSAIDs) (1, 35), and consistent with prior common causative drugs described in MDIS and MDAS (11, 19, 20). While HSRs in MDAS patients not surprisingly included urticaria, angioedema, and rash, we observed a high prevalence of SCAR, consistent with early MDAS descriptions as a syndrome that occurred after drug rash eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome or other severe reactions (6, 9, 10, 19).

Depression affects approximately 10% of Americans, with a lifetime prevalence from 16-30% (36–38). We found that depression was associated with both MDIS and MDAS, with a 50% and 40% increased odds respectively. The association remained strong and consistent for both MDIS and MDAS in all sensitivity analyses. A prior retrospective study in a large US healthcare system found that psychiatry visits were more common in patients with MDIS (from 38% to 47% depending on MDIS severity) compared to patients with no drug allergies (20%) (2). Smaller, prospective studies using psychodiagnostic tests reported high levels of depression — as well as anxiety, lower quality of life, and alexithymia — in patients with drug allergies compared to controls (22, 23). Our study confirms a significant association between depression and MDIS and MDAS. Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, the most commonly used antidepressants) are commonly reported as causing drug intolerances and can also cause HSRs, given that only 7% of MDIS patients were intolerant to SSRIs and 1% of MDAS patients reported an SSRI HSR, the associations identified in this study do not appear to be due to depression medications themselves conferring a high intolerance or hypersensitivity risk. Instead, the reactions reported in depression may be related to physical manifestations of depression itself, which can range from nonspecific medical symptoms like nausea to medical diagnoses with somatic components, such as irritable bowel syndrome or fibromyalgia (39–42). Implementation of psychiatric screening tools for depression, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (43), may be useful in the evaluation and treatment of both MDIS and MDAS patients.

The presence of anxiety, which impacts approximately 10% of Americans at some point in their lifetime (36–38), increased odds of MDIS by 70%, an association that was consistent throughout various sensitivity analyses. Further, the odds of anxiety increased significantly in a step-wise fashion with the number of drug class intolerances reported. Previously, somatization, reduced quality of life, and anxiety have been shown to be prominent in patients with drug intolerance (24). MDIS patients may benefit from clinician reassurance or specialized psychiatric support, especially with the introduction of new therapeutic medications. Clinical assessments of MDIS patients may benefit from structured causality assessments, such as the Naranjo scale (44). Placebo-controlled oral challenges have been useful in drug allergy evaluations for referral MDAS populations (45, 46); MDIS patients may similarly benefit from placebo-controlled oral challenges or tolerance testing (47).

By contrast, anxiety was not significantly related to MDAS, and there was no discernable relationship between number of HSRs and odds of anxiety. This finding may suggest another physiologic driver behind patients having multiple drug HSRs. Previous reports have hypothesized that MDAS patients have histamine-releasing factors, different baseline tolerances for small chemicals, drug-induced interferon gamma release, and pre-activated CD4 T cells (10, 14, 20, 28, 48). EHR-based identification of MDAS patients could facilitate future research into these, and other, mechanistic hypotheses.

This study has several potential limitations. The use of EHR-based data can lead to miscategorization and lack of specificity. We were reliant on billing codes for patient diagnoses, including the primary variables of interest (depression and anxiety). However, codes used in this study were informed by prior studies, and we performed a variety of sensitivity analyses around variable definitions to assess the stability of our findings. EHR allergies in PEAR were used to define MDIS, MDAS, and reaction types, but EHR allergy documentation is often inaccurate. Reactions often lack specificity and data are uncommonly entered by allergy specialists and verified by allergy testing (7). Covariate assessment may be incomplete because PHS is not a closed healthcare system; however, by establishing patient visit criteria over the study horizon, we improved data capture opportunities. However, without knowing the when the reported allergies occurred, some important covariates, such as concomitant medications, could not be assessed in risk factor analyses. We were also unable to identify whether the diagnosis of MDIS or MDAS was before or after psychiatric diagnoses. Finally, these data represent one healthcare system in the northeastern United States, and findings may not be generalizable to other settings.

In summary, we identified a population of patients with MDIS and MDAS using EHR data; patients had drug culprits and reactions that were generally similar to previously described cohorts that used different identification and verification methods. We found a consistent association between anxiety and depression and MDIS; by contrast, depression, but not anxiety, was associated with MDAS. Our findings emphasize the importance of psychological screening and support for MDIS and MDAS patients, and identify an expanded role for medication tolerance testing. Physiologic causes that may underlie MDAS warrant additional prospective study. Finally, given the heterogeneity of definitions proposed and used for patients with multiple drug intolerance and hypersensitivity, to facilitate future MDIS, MDAS, and MDH research, adoption of standardized terminology is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Multivariable association between Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome (MDIS), Multiple Drug Allergy Syndrome (MDAS), and anxiety and depression.

| MDIS* | MDAS* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI]† | p-value | OR [95% CI]† | p-value | |

| Anxiety | 1.72 [1.65, 1.80] | <0.001 | 1.13 [0.99, 1.30] | 0.08 |

| Depression | 1.46 [1.41, 1.52] | <0.001 | 1.41 [1.28, 1.56] | <0.001 |

| Both anxiety and depression | 1.97 [1.86, 2.08] | <0.001 | 1.13 [0.92, 1.38] | 0.24 |

| Neither anxiety nor depression | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Age (every 10 years) | 1.36 [1.36, 1.37] | <0.001 | 1.24 [1.22, 1.26] | <0.001 |

| Female | 2.97 [2.89, 3.04] | <0.001 | 2.88 [2.69, 3.08] | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Asian | 0.53 [0.49, 0.58] | <0.001 | 0.68 [0.56, 0.82] | <0.001 |

| Black | 0.75 [0.71, 0.78] | <0.001 | 0.88 [0.77, 0.99] | 0.03 |

| Hispanic | 0.54 [0.50, 0.58] | <0.001 | 0.76 [0.64, 0.90)] | 0.001 |

| Unknown / other | 0.74 [0.72, 0.77] | <0.001 | 0.73 [0.66, 0.82] | <0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Single | 1.07 [1.04, 1.10] | <0.001 | 0.92 [0.86, 0.99] | 0.02 |

| Divorce / separated | 1.18 [1.14, 1.23] | <0.001 | 1.09 [0.99, 1.21] | 0.08 |

| Widow | 0.87 [0.84, 0.91] | <0.001 | 0.74 [0.66, 0.83] | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.14 [1.09, 1.18] | <0.001 | 0.93 [0.83, 1.04] | 0.21 |

| Office visits | ||||

| 0 visits | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 1 to 5 visits | 1.00 [0.96, 1.03] | 0.78 | 0.92 [0.83, 1.03] | 0.16 |

| 6 to 10 visits | 1.05 [1.01, 1.10] | 0.02 | 1.31 [1.16, 1.48] | <0.001 |

| More than 10 visits | 1.26 [1.22, 1.30] | <0.001 | 2.00 [1.84, 2.18] | <0.001 |

| Inpatient visits | ||||

| 0 visits | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 1 to 5 visits | 1.29 [1.25, 1.33] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.92, 1.07] | 0.79 |

| 6 to 10 visits | 1.52 [1.46, 1.58] | <0.001 | 0.96 [0.85, 1.08] | 0.51 |

| More than 10 visits | 1.87 [1.81, 1.94] | <0.001 | 1.05 [0.94, 1.17] | 0.39 |

| Outpatient emergency room visits | ||||

| 0 visits | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 1 to 5 visits | 1.08 [1.05, 1.11] | <0.001 | 0.93 [0.86, 1.00] | 0.05 |

| 6 to 10 visits | 1.31 [1.25, 1.38] | <0.001 | 0.93 [0.79, 1.10] | 0.39 |

| More than 10 visits | 1.62 [1.53, 1.73] | <0.001 | 0.86 [0.68,1.08] | 0.18 |

| Habits | ||||

| Smoking | 1.21 [1.18, 1.24] | <0.001 | 1.12 [1.05, 1.19] | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.99 [0.91, 1.07] | 0.82 | 1.02 [0.80, 1.31] | 0.86 |

| Drug use | 1.27 [1.18, 1.38] | <0.001 | 1.14 [0.89, 1.47] | 0.30 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic urticaria angioedema | 1.79 [1.60, 2.01] | <0.001 | 2.61 [2.05, 3.31] | <0.001 |

| Autoimmune disease | 1.66 [1.59, 1.73] | <0.001 | 1.27 [1.13, 1.42] | <0.001 |

| Renal impairment | 1.30 [1.24, 1.35] | <0.001 | 1.17 [1.02, 1.35] | 0.03 |

| Cardiac condition | 1.18 [1.15, 1.21] | <0.001 | 1.00 [0.92, 1.09] | 0.99 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.10 [1.06, 1.14] | <0.001 | 0.94 [0.82, 1.06] | 0.30 |

| Malignancy | 1.05 [1.03, 1.08] | <0.001 | 1.01 [0.95, 1.08] | 0.77 |

| Diabetes | 0.75 [0.71, 0.78] | <0.001 | 0.75 [0.66, 0.86] | <0.001 |

MDIS patients have only MDIS and MDAS patients have only MDAS. The 3,171 patients with both MDIS and MDAS were excluded from risk factor analyses (see methods).

Compared to control patient without MDIS or MDAS (n=693,810, see methods).

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Samuel Karmiy and Leigh Kowalski for their assistance with data abstraction, and Jessica A. Gold, MD, MS for her thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) R01HS022728, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) K01AI125631, and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the AHRQ, NIAID/NIH, nor the AAAAI Foundation.

Abbreviations

- EHR

Electronic Health Record

- MDIS

Multiple Drug Intolerance Syndrome

- MDAS

Multiple Drug Allergy Syndrome

- NSAID

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug

- PHS

Partners HealthCare System

- PEAR

Partners Enterprise Allergy Repository

- HSR

Hypersensitivity Reaction

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseasesninth edition

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- OR

Odds Ratio

- SSRI

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor

Footnotes

Author Contributions: KGB, YL, WWA, AB, SG, CAC and LZ designed the study. KGB and YL performed the literature review. WWA and LZ performed data extraction. YL and YC performed statistical analyses. KGB, YL, YC, and CAC interpreted the results. KGB drafted the first report. YL, WWA, YC, AB, SG, CAC and LZ assisted with interpretation and revision of the report. KGB obtained the funding. All authors were involved in the review and approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interests: None

DR. KIMBERLY G BLUMENTHAL (Orcid ID : 0000-0003-4773-9817)

References

- 1.Zhou L, Dhopeshwarkar N, Blumenthal KG, Goss F, Topaz M, Slight SP, et al. Drug allergies documented in electronic health records of a large healthcare system. Allergy. 2016;71:1305–13. doi: 10.1111/all.12881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macy E, Ho NJ. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome: Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and management. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macy E. Multiple antibiotic allergy syndrome. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:533–43. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange L, Koningsbruggen SV, Rietschel E. Questionnaire-based survey of lifetime-prevalence and character of allergic drug reactions in German children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:634–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes E, Cardoso MF, Praca F, Gomes L, Marino E, Demoly P. Self-reported drug allergy in a general adult Portuguese population. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1597–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pichler WJ, Daubner B, Kawabata T. Drug hypersensitivity: Flare-up reactions, cross-reactivity and multiple drug hypersensitivity. J Dermatol. 2011;38:216–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumenthal KG, Park MA, Macy EM. Redesigning the allergy module of the electronic health record. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:126–31. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Studer M, Waton J, Bursztejn AC, Aimone-Gastin I, Schmutz JL, Barbaud A. [Does hypersensitivity to multiple drugs really exist?] Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiriac AM, Demoly P. Multiple drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:323–9. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283630c36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gex-Collet C, Helbling A, Pichler WJ. Multiple drug hypersensitivity—proof of multiple drug hypersensitivity by patch and lymphocyte transformation tests. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2005;15:293–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omer HM, Hodson J, Thomas SK, Coleman JJ. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome: A large-scale retrospective study. Drug Saf. 2014;37:1037–45. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dioun AF. Management of multiple drug allergies in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2012;12:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gell PGH, Coombs RA. The classification of allergic reactions underlying disease. First. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asero R, Tedeschi A, Lorini M, Caldironi G, Barocci F. Sera from patients with multiple drug allergy syndrome contain circulating histamine-releasing factors. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2003;131:195–200. doi: 10.1159/000071486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demoly P, Adkinson NF, Brockow K, Castells M, Chiriac AM, Greenberger PA, et al. International consensus on drug allergy. Allergy. 2014;69:420–37. doi: 10.1111/all.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenthal KG, Lai KH, Huang M, Wallace ZS, Wickner PG, Zhou L. Adverse and hypersensitivity reactions to prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents in a large health care system. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:737–43e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly WN. Potential risks and prevention, Part 1: Fatal adverse drug events. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58:1317–24. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.14.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neukomm CB, Yawalkar N, Helbling A, Pichler WJ. T-cell reactions to drugs in distinct clinical manifestations of drug allergy. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2001;11:275–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiavino D, Nucera E, Roncallo C, Pollastrini E, De Pasquale T, Lombardo C, et al. Multiple-drug intolerance syndrome: clinical findings and usefulness of challenge tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:136–42. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halevy S, Grossman N. Multiple drug allergy in patients with cutaneous adverse drug reactions diagnosed by in vitro drug-induced interferon-gamma release. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:865–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nettis E, Colanardi MC, Paola RD, Ferrannini A, Tursi A. Tolerance test in patients with multiple drug allergy syndrome. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2001;23:617–26. doi: 10.1081/iph-100108607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patriarca G, Schiavino D, Nucera E, Colamonico P, Montesarchio G, Saraceni C. Multiple drug intolerance: Allergological and psychological findings. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1991;1:138–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Pasquale T, Nucera E, Boccascino R, Romeo P, Biagini G, Buonomo A, et al. Allergy and psychologic evaluations of patients with multiple drug intolerance syndrome. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7:41–7. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassel JC, Danner D, Hassel AJ. Psychosomatic or allergic symptoms? High levels for somatization in patients with drug intolerance. J Dermatol. 2011;38:959–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acker WW, Plasek JM, Blumenthal KG, Lai KH, Topaz M, Seger DL, et al. Prevalence of food allergies and intolerances documented in electronic health records. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.006. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuperman GJ, Marston E, Paterno M, Rogala J, Plaks N, Hanson C, et al. Creating an enterprise-wide allergy repository at Partners HealthCare System. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:376–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumenthal KG, Acker WW, Li Y, Holtzman NS, Zhou L. Allergy entry and deletion in the electronic health record. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:380–1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daubner B, Groux-Keller M, Hausmann OV, Kawabata T, Naisbitt DJ, Park BK, et al. Multiple drug hypersensitivity: Normal Treg cell function but enhanced in vivo activation of drug-specific T cells. Allergy. 2012;67:58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asero R. Detection of patients with multiple drug allergy syndrome by elective tolerance tests. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;80:185–8. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62953-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szczerbinska K, Hirdes JP, Zyczkowska J. Good news and bad news: Depressive symptoms decline and undertreatment increases with age in home care and institutional settings. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:1045–56. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182331702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17:327–35. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/bbandelow. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamers F, van Oppen P, Comijs HC, Smit JH, Spinhoven P, van Balkom AJ, et al. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:341–8. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Topaz M, Goss F, Blumenthal K, Lai K, Seger DL, Slight SP, et al. Towards improved drug allergy alerts: Multidisciplinary expert recommendations. Int J Med Inform. 2017;97:353–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumenthal KG, Saff RR, Banerji A. Evaluation and management of a patient with multiple drug allergies. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:197–203. doi: 10.2500/aap.2014.35.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macy E, Poon KYT. Self-reported antibiotic allergy incidence and prevalence: Age and sex effects. Am J Med. 2009;122:778e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current depression among adults—United States, 2006 and 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strine TW, Mokdad AH, Balluz LS, Gonzalez O, Crider R, Berry JT, et al. Depression and anxiety in the United States: Findings from the 2006 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1383–90. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169–84. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. The association between anxiety, depression, and somatic symptoms in a large population: The HUNT-II study. Psychosomatic medicine. 2004;66:845–51. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145823.85658.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: A meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:528–33. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katon W, Lin EH, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kapfhammer HP. Somatic symptoms in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:227–39. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.2/hpkapfhammer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): A diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1596–602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iammatteo M, Ferastraoaru D, Koransky R, Alvarez-Arango S, Thota N, Akenroye A, et al. Identifying allergic drug reactions through placebo-controlled graded challenges. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:711–7e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lombardi C, Gargioni S, Canonica GW, Passalacqua G. The nocebo effect during oral challenge in subjects with adverse drug reactions. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;40:138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liccardi G, Senna G, Russo M, Bonadonna P, Crivellaro M, Dama A, et al. Evaluation of the nocebo effect during oral challenge in patients with adverse drug reactions. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14:104–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tedeschi A, Lorini M, Suli C, Cugno M. Detection of serum histamine-releasing factors in a patient with idiopathic anaphylaxis and multiple drug allergy syndrome. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2007;17:122–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.