Abstract

Background

Human Bocavirus (HBoV) is an emerging virus discovered in 2005 from individuals suffering gastroenteritis and respiratory tract infections. Numerous studies related to the epidemiology and pathogenesis of HBoV have been conducted worldwide. This review reports on HBoV studies in individuals with acute gastroenteritis, with and without respiratory tract infections in Africa between 2005 and 2016.

Material and Method

The search engines of PubMed, Google Scholar, and Embase database for published articles of HBoV were used to obtain data between 2005 and 2016. The search words included were as follows: studies performed in Africa or/other developing countries or/worldwide; studies for the detection of HBoV in patients with/without diarrhea and respiratory tract infection; studies using standardized laboratory techniques for detection.

Results

The search yielded a total of 756 publications with 70 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Studies included children and individuals of all age groups. HBoV prevalence in Africa was 13% in individuals suffering gastroenteritis with/without respiratory tract infection.

Conclusion

Reports suggest that HBoV infections are increasingly being recognized worldwide. Therefore, surveillance of individuals suffering from infections in Africa is required to monitor the prevalence of HBoV and help understand the role of HBoV in individuals suffering from gastroenteritis with/without respiratory tract infection.

1. Introduction

Diarrhea is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children worldwide [1, 2]. Diarrhea is the third major cause of childhood mortality in children less than 5 years of age especially in Africa and developing countries [3–5]. The modes of transmission include ingestion of contaminated food or water (e.g., via flies, inadequate sanitation facilities, sewage and water treatment systems, and cleaning food with contaminated water), direct contact with infected feces (fecal-oral route), person-to-person contact, and poor personal hygiene [6, 7].

According to WHO [1], approximately 90% of the estimated 2.2 million of deaths caused by diarrheal infections in children less than 5 years of age are related to poor sanitation and hygiene behaviors worldwide. While the mortality due to diarrheal diseases has declined significantly in children over the past twenty years in developed countries [8, 9], the incidence of childhood diarrhea in developing countries has not decreased [1, 2]. Those who survive these illnesses have repeated infections by enteric pathogens which remains a critical factor leading to serious lifelong health consequences [10] and eventually result in death [11]. Viruses are recognized as major cause of gastroenteritis, particularly in children, and the number of viral agents associated with diarrheal disease in humans has increased progressively. Viruses such as rotavirus, norovirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus that cause diarrhea have been reported worldwide [11].

The Human Bocavirus (HBoV) is a viral agent that has been reported worldwide in various studies as a potential cause of diarrhea outbreaks [5, 12–18]. The HBoV is a member of the Parvoviridae family, Parvovirinae subfamily, and the genus of Bocavirus [19–21]. The family Parvoviridae includes small, nonenveloped, icosahedral viruses with 5.3 kb single stranded DNA genome containing three open reading frames (ORFs); the first ORF, at the 5′ end, encodes NS1, a nonstructural protein [22]. The second ORF encodes NP1, a second nonstructural protein. The third ORF, at the 3′ end, encodes the two structural capsid viral proteins (VPs), VP1 and VP2 [23, 24]. There are currently four Bocavirus species identified worldwide, namely, HBoV1, HBoV2, HboV3, and HBoV4 [5, 25–28]. HBoV was first discovered in 2005 in children with acute respiratory tract infection [28]. In 2007, HBoV was detected in children suffering from gastroenteritis with and without symptoms of respiratory tract infections [14, 29–31]. Primary infection with HBoV occurs early in life in children between 6–24 months of age [32–34]; however, older children and adults can also be infected [28, 35]. Currently there is no specific approved treatment or vaccine for HBoV infection [25, 36, 37]. Since its discovery, the virus was mainly associated with respiratory tract infections, but recent studies have revealed the involvement of the virus in gastroenteritis. These studies indicate that only HBoV2, HBoV3, and HBoV4 strains of the virus are mainly involved in gastroenteritis [37–39]. Currently, there is limited data on ELISA method for the detection of the virus. HBoV detection has been done by conventional PCR [17, 28, 40, 41] and real-time PCR [42–45]. While HBoV epidemiological studies have shown evidence for widespread exposure to the virus, the causative role of HBoV in respiratory tract disease and gastroenteritis is still under investigation [46]. Proven evidence is difficult to obtain without an in vitro culture system and animal model [28, 47–49].

The prevalence of HBoV has been reported in Europe [50, 51], America [17, 41], Asia [34, 52], Australia [40, 53], Africa [54], and the Middle East [18], ranging from 1.5% to 19.3% [17, 55]. This review is a summary of reported HBoV studies in individuals with acute gastroenteritis, with and without respiratory tract infections looking specifically to studies in Africa to determine the role of HBoV in diarrheal outbreaks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

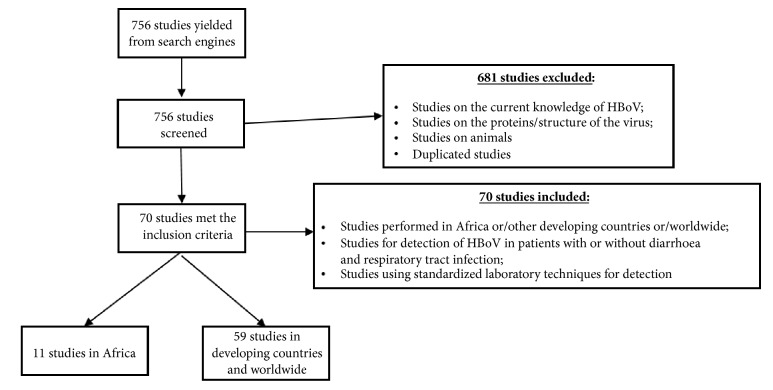

A literature search of selected studies that investigated HBoV in Africa, in other developing countries and worldwide was performed using the following terms: Human + Bocavirus + Africa + Developing countries + Worldwide on PubMed, Google scholar and Embase. This search yielded 756 publications (Figure 1). The first search was performed for HBoV + Africa, the second search was HBoV + other developing countries, and the third search was HBoV + worldwide. Keywords used included Human Bocavirus, Bocavirus, and Human parvovirus combined for each (Africa; Developing country; Worldwide). To avoid leaving out any studies not found in major scientific databases, Google search was also used. After reviewing each article, studies were selected if they met the following inclusion criteria:

(i) Studies performed in Africa/other developing countries/worldwide between 2005 and 2016.

(ii) Studies for the detection of HBoV in patients with or without diarrhea and respiratory tract symptoms. Diarrhea defined as the passage of loose or watery stools, at least three times in a 24-h period [56].

(iii) Studies using standardized laboratory techniques for detection of HBoV including PCR, real-time-PCR, and Multiplex PCR (m-PCR).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of search engine used.

3. Data Extraction

Information extracted from the inclusion studies included country where study was done, time period of study, age range of participants, study setting (rural/urban/periurban), sampled population (number of included samples), method used for detection, clinical symptoms, sample type, and HBoV subtype.

4. Statistical Analysis

All analysis were conducted using R programming environment for data analysis and graphics Version 3.5.0 [57] to calculate random and fixed effects. Function “rma” from the package Metafor [58] was used to calculate heterogeneity between studies and generate a forest plot. Heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran's Q test.

5. Results and Discussion

Between 2005 and 2016 a total of 756 studies were published in Africa, other developing countries and worldwide. From these studies, 70 studies met the inclusion criteria of which 11 studies were from African countries and 59 studies combined were for other developing countries and worldwide. None of the studies reported on outbreaks (Tables 1, 2, and 3).

Table 1.

Human Bocavirus globally, studies published between 2005 and 2016.

| Country | Study period | Setting | Age range | Sampled population | Tested samples | Positive samples (%) | Hospitalized | Outpatient | Sample type | Symptoms | Detection method | HBoV type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 2001 | - | - | children | 197 | 125 (63.5%) | 197 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | Nested PCR | 1,2,3 | [25] |

| 2003-2004 | Urban | ≤ 5 years | children | 700 | 41 (6%) | 604 | 96 | Nasal–throat, stool, whole blood | Respiratory infection/diarrhea | Real-time PCR | 1 | [26] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| America | 2004 | Urban | < 2 years | children | 1271 | 22 (1.7%) | 1271 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [41] |

| - | Peri-urban | All | children | 641 | 101 (16%) | - | - | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1,2,3,4 | [74] | |

| 2007-2008 | 2-11 years | children | 149 | 7 (5%) | - | 149 | Throat, Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [66] | ||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Argentina | 2011 | Peri-urban | ≤ 2 years | children | 222 | 15 (7%) | 222 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [76] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Argentina, Nicaragua, Peru | - | - | < 6 years | children | 568 | 61 (11%) | 568 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR | 1 | [77] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Brazil | 2004-2007 | Peri-urban | ≤ 2 years | children | 397 | 3 (0.76%) | - | 397 | Nasal, throat | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [62] |

| 2003-2005 | Peri-urban | <15 years | children | 705 | 14 (2%) | 285 | 420 | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1 | [15] | |

| 1998-2004 | Urban | < 5 years | children | 762 | 44 (5.8%) | 762 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1,3 | [78] | |

| 2008 | Urban | <2 years | children | 511 | 55 (11%) | 511 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1,2,3 | [79] | |

| 2010-2012 | Urban/rural | ≤18 | children | 200 | 67 (33.9%) | 200 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time (RT-PCR) | 1 | [80] | |

| 2010-2011 | Urban/rural | 1-14 years | children | 121 | 36 (29.8%) | 121 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [81] | |

| 2005-2007 | Urban/rural | All | Children/adults | 1015 | 49 (4.8%) | 1015 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [82] | |

| 2008-2009 | Urban | < 5 years | children | 407 | 77 (19%) | 407 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [83] | |

| 2006-2007 | Urban/rural | All | Children/adults | 90 | 2 (2%) | 90 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1 | [84] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Cambodia | 2009-2010 | Urban | All | Children/adults | 292 | 162 (55%) | 292 | - | Nasal, throat | Respiratory tract infection | Multiplex PCR | 1 | [85] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Cameroon | 2011-2013 | Urban | ≤15 years | children | 347 | 37 (11%) | 347 | - | Throat | Respiratory tract infection | Multiplex PCR | 1 | [86] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| China | 2009-2013 | Urban/rural | All | Children/adults | 29248 | 551 (2%) | 29 248 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [87] |

| 2004-2005 | Urban | < 18 years | children | 203 | 83 (40%) | 203 | - | Stool, Nasal | Respiratory infection/diarrhea | PCR | 1 | [88] | |

| 2007-2008 | Urban | ≤15 years | children | 235 | 21 (9%) | 235 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1,2 | [89] | |

| 2009-2012 | Urban/rural | All | Children/adults | 14237 | 180 (1.26%) | 14237 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [23] | |

| 2012-2013 | Urban/rural | <14 years | children | 4130 | (16.7%) | 4130 | - | Throat | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [90] | |

| 2012 | Peri-urban | ≤ 5 years | children | 122 | - | - | 122 | Stool | Diarrhea | Multiplex real-time PCR | 1 | [91] | |

| 2009-2014 | - | All | Children/adults | 12502 | 225 (2%) | 12502 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [92] | |

| 2009-2014 | Urban | <14 years | children | 4242 | 125(3%) | 4242 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR | 1 | [93] | |

| 2012-2013 | Urban | < 6 years | children | 346 | 60 (17.34%) | 346 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1,2 | [94] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Egypt | 2013-2014 | Urban | ≤ 36 months | children | 95 | 54 (56.8%) | 95 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [8] |

| 2013-2015 | Urban | 1 month-2 years | children | 100 | 2(2%) | 100 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1 | [95] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Finland | 2000-2002 | Urban | 3 months-15 years | children | 117 | 24 (49%) | 117 | - | Nasal, serum | Respiratory tract infection | Qualitative PCR | 1 | [96] |

| 2010 | Urban | All | Children/adults | 250 | 4 (1.6%) | 250 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | Multiplex real-time quantitative PCR | 1,2,3,4 | [27] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| France | 2003-2004 | - | < 5 years | children | 589 | 9 (1.5%) | 589 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [51] |

| 2010-2011 | Urban | All | Children/adults | 1465 | 5 (0.3%) | 1465 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Multiplex PCR | 1 | [97] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Germany | 2007 | Urban | - | children | 834 | 115 (14%) | 834 | - | Stool, nasal, serum | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [98] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Hong Kong | 2004-2005 | Periurban | - | children | 1178 | 12 (1%) | 1178 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR; PCR | 1 | [99] |

| 2004-2005 | Urban | <18 years | children | 3035 | 103 (3.4%) | 3035 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [88] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Iran | 2009-2011 | Peri-urban | 2-108 months old | children | 80 | 6(8%) | 80 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | Real-time PCR | 1 | [100] |

| 2010-2011 | Urban | <4 years | children | 200 | 16 (8%) | 200 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | Real-time PCR | 1 | [101] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Istanbul | 2014-2015 | Urban/rural | All | Children/adults | 845 | 91 (11%) | 845 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR | 1 | [102] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Italy | 2005-2006 | Urban | - | Children/adults | 426 | 42 (9.9%) | 426 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [103] |

| 2000-2006 | Urban | All | Children/adults | 355 | 4.5%, | 355 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [30] | |

| 2004-2007 | Urban/rural | <14 years | children | 415 | 34 (8.2%) | 415 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [104] | |

| 2011-2012 | Urban | All | Children/adults | 689 | 14 (2%) | 689 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | Real time PCR | 1 | [105] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| India | 2010-2011 | Rural/Peri-urban | 0–6 years | children | 300 | 2 (0.67%) | 300 | - | Throat | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [106] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Jordan | 2003-2006 | Peri-urban | < 5years | children | 326 | 57 (17%) | 326 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [18] |

| 2007 | Peri-urban | ≤13 years | children | 220 | 20 (9%) | 220 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR/ real-time PCR | 1 | [107] | |

| 2003-2004 | Urban | ≤ 5 years | children | 326 | 57 (17%) | 326 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR | 1 | [108] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Japan | 2005-2011 | Peri-urban | 0-136 months | children | 850 | 132 (15.5%) | 850 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Nested PCR | 1,2,3,4 | [73] |

| 2007–2009 | Urban/rural | <2 years | children | 402 | 34 (8.5%) | 402 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [109] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kenya | 2013 | Rural | ≤5 years. | children | 125 | 21 (17%) | 125 | - | Throat | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [59] |

| 2007-2009 | Urban | All age group | Children/adults | 384 | 7 (1.8%) | - | 384 | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1,2,3,4 | [3] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 1993–1996 | Urban/rural | All | Children/adults | 4380 | 324 (7.4%) | 4380 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | Real time PCR | 1,2,3 | [110] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Malaysia | 2012 | Urban/rural | Children | children | 1 | 1 (99%) | 1 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [111] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Netherland | 2005-2006 | Peri-urban | 3 months-6 years | children | 257 | 4 (1.6%) | - | 257 | Nasal | Respiratory infection/diarrhea | Real time PCR | 1 | [112] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Pakistan | 2008 | Rural | - | Children/adults | 98 | - | - | - | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1,2 | [113] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Philippines | 2008-2009 | Urban | 8 days to 13 years | children | 1242 | 2 (0.16%) | 1242 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [114] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Senegal | 2009-2011 | Urban | All age group | Children/adults | 232 | 1 (0.4%) | 232 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-Time PCR | 1 | [115] |

| 2007 | Rural | ≤5 | children | 82 | 1 (1.2%) | 82 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [4] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| South Africa | 1998-2000 | Urban | <2 | children | 1460 | 332 (22.8%) | 1460 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | RT-PCR | 1 | [116] |

| 2004 | Urban | 2 days–12 years | children | 341 | 13 (37%) | 341 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [54] | |

| 2004-2005 | Urban | 2 months to 6 years | children | 242 | 18 (7.4%) | 242 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Nested PCR | 1 | [117] | |

| 2009-2010 | Rural | 3 months to <5 years | children | 260 | 30 (11.5%) | - | 260 | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [118] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Shanghai | 2009-2012 | Peri-urban | ≤ 5 years | children | 554 | 39 (7.0%) | 554 | - | Nasal, stool, whole blood | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR/ PCR | 1 | [29] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Spain | 2005-2006 | Urban | <3 years | children | 527 | 48 (9.1%) | 527 | - | Stool, Nasal | Respiratory tract infection/diarrhea | PCR | 1 | [14] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Sweden | 2000-2002 | Urban | 3 months to 15 years | children | 259 | 49 (19%) | 259 | - | Nasal, serum | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [42] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Taiwan | 2008-2009 | Peri-urban | 5 months-9 years | children | 705 | 35 (5%) | - | 705 | Throat | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [119] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Thailand | 2006 | Urban | 1 month-9 years | children | 252 | 18 (7%) | 252 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [20] |

| 2005-2007 | Peri-urban | 2 months-5 years | children | 427 | 2 (0.4%) | 225 | 202 | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1 | [33] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Turkey | 2015 | Urban | Five months | children | 1 | 1 (99%) | 1 | - | Nasal, stool | Respiratory tract infection/diarrhea | Multiplex PCR | 1,2,3,4 | [120] |

Table 2.

Human Bocavirus studies in other developing countries between 20005 and 2016.

| Country | Study period | Setting | Age range | Sampled population | Tested samples | Positive samples (%) | Hospitalized | Outpatient | Sample type | Symptoms | Detection method | HBoV type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina, Nicaragua and Peru | - | - | < 6 years | children | 568 | 132 (23%) | 568 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR | 1 | [77] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Brazil | 2007 | Rural | <3 years | children | 260 | 27 (10.4) | 260 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [121] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Cambodia | 2009-2010 | - | All | Children/adults | 292 | 9 (3%) | 292 | - | Throat swabs, nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Multiplex real-time PCR | 1 | [85] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| China | 2012 | Peri-urban | ≤ 5 years | children | 122 | - | - | - | Stool | Diarrhea | Multiplex real-time PCR | 1 | [91] |

| 2009-2014 | - | All | Children/adults | 12502 | 225 (2%) | 12502 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [92] | |

| 2009-2014 | Urban | <14 years | children | 4242 | 125 (3%) | 4242 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR | 1 | [98] | |

| 2012-2013 | Urban | < 6 years | children | 346 | 60 (17.34%) | 346 | - | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1,2 | [94] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| India | 2010-2011 | Rural/Peri-urban | 0–6 years | children | 300 | 2 (0.6 %) | 300 | - | Throat swabs | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [106] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Jordan | 2003-2004 | Urban | ≤ 5 years | children | 326 | 57 (17%) | 326 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real time PCR | 1 | [108] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Philippines | 2008-2009 | Urban | 8 days to 13 years | children | 1242 | 2 (0.16) | 1242 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [114] |

Table 3.

Human Bocavirus studies in Africa between 2005 and 2016.

| Country | Study period | Setting | Age range | Sampled population | Tested samples | Positive Samples (%) | Hospitalized | Outpatient | Sample type | Symptoms | Detection method | HBoV type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameroon | 2011-2013 | Urban | Children aged ≤15 years | children | 347 | 37 (10.6%) | 347 | - | Throat | Respiratory tract infection | Multiplex PCR | 1 | [86] |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Egypt | 2013-2015 | Urban | 1 month-2 years | children | 100 | 2 (2%) | 40 (40%) | 60 (60%) | Stool | Diarrhea | PCR | 1 | [95] |

| 2013-2014 | Urban | ≤ 36 months | children | 95 | 54 (56%) | 11 (40%) | 43 (63%) | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-time PCR | 1 | [8] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Kenya | 2013 | Urban | ≤5 | children | 125 | 21 (16.8%) | 125 | - | Throat | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [59] |

| 2007-2009 | Urban | All age group | Children/adults | 384 | 7 (1.8%) | - | 384 | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1,2,3,4 | [3] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Senegal | 2007 | Rural | ≤5 | children | 82 | 1 (1.2%) | - | 82 | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [4] |

| 2009-2011 | Urban | All age group | Children/adults | 232 | 1 (0.43%) | - | 232 | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Real-Time PCR | 1 | [115] | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| South Africa | 1998-2000 | Urban | <2 | children | 1460 | 174 (22.8%) | 1460 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | RT-PCR | 1 | [116] |

| 2004 | Urban | 2 days–12 years | children | 341 | 38 (11%) | 341 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [54] | |

| 2004-2005 | Urban | 2 months to 6 years | children | 242 | 18 (7.4%) | 242 | - | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | Nested PCR | 1 | [117] | |

| 2009-2010 | Rural | 3 months to <5 years | children | 260 | 30 (11.5%) | - | 260 | Nasal | Respiratory tract infection | PCR | 1 | [118] | |

All 70 studies were reports on children ≤5 years of age (33%; 23/70) and children and individuals of all ages, ≥5 years (67%; 47/70). The majority of the studies (78%; 55/70) were reports on patients suffering from respiratory tract infection and 21.4% (15/70) were reports on patients suffering from diarrheal disease. Fifty-four studies (77%; 54/70) were done in urban settings and 23% (16/70) were done in rural settings (Table 1). The most reported HBoV subtype was HBoV1 (100%; 70/70), followed by HBoV2 (16%; 11/70), HBoV3 (13%; 9/70), and HBoV4 (7%; 5/70) (Table 1). A total of 54% (36/67) studies were done on samples collected from nasal swabs, 7% (5/67) were done on samples collected from throat swabs, 22% (15/67) were done on stool samples, 4% (3/67) were combined nasal/throat samples, 3% (2/67) were combined stool/nasal samples, 6% (4/67) were combination of nasal/stool/serum samples, and 3% (3/67) were a combination of nasal/serum samples.

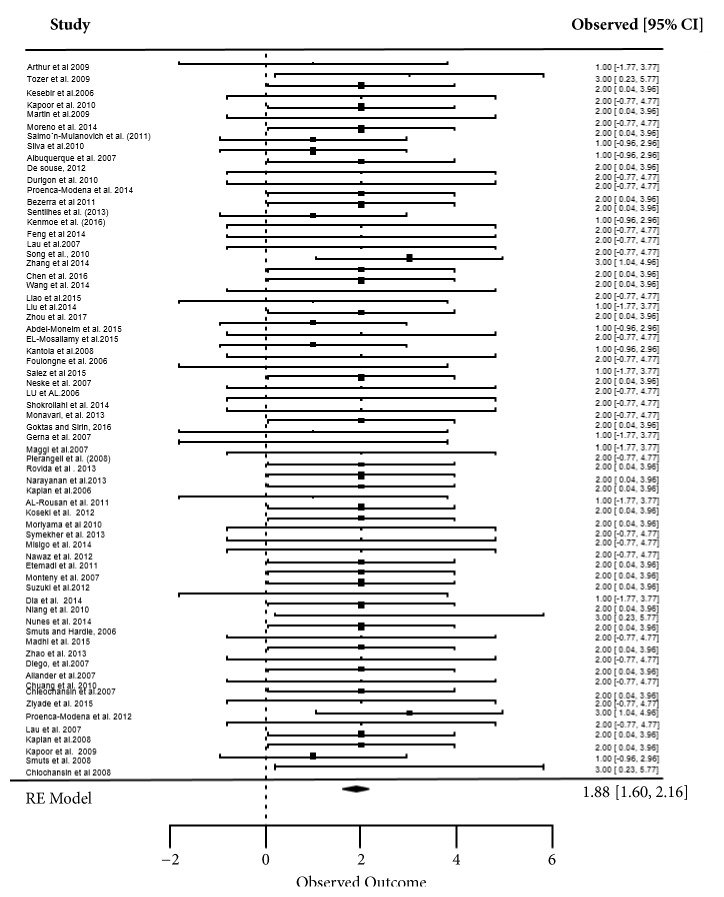

Meta-analysis was done to provide transparent, objective, and replicable summaries of the study findings. From all the 70 studies, 66 had sufficient information to enable statistical analysis. As shown in Figure 2 with the dispersion in study prevalence, there was a low heterogeneity among the studies (Cochran Q = 12.2800 [df = 65] P-Val = 1). Apart from the observed increase in the prevalence of HBoV, none of the other drivers (including age, setting, symptoms, method of detection, and hospitalization) achieved statistical significance. The test for overall effect was Z = 13.29 (P<0.0001) which was highly significant in the findings.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for prevalence studies in detection of Human Bocavirus.

Ten studies were from other developing countries of which eight studies (80%) reported on patients suffering from respiratory tract infection and two studies (20%) reported on patients suffering from diarrheal disease. All ten of the studies focused only on children (100%; 10/10) (Table 2). All studies in other developing countries worked on hospitalized patients (Table 2). A total of 70% (7/10) of the studies collected nasal swabs, 20% collected throat swabs, and 20% of the studies collected stool samples. The most sampled population was children ≤ 6 years of age (Table 2). Majority 60% (6/10) were done in urban setting in other developing countries while 40% (4/10) were done in rural settings. Eight (80%) of the studies reported on patients suffering from respiratory tract infections (Table 2). In other developing countries, HBoV was reported in Argentina 10% (1/10), Cambodia 10% (1/10), China 40% (4/10), India 10% (1/10), Jordan 10%(1/10), and the Philippines 10%(1/10).

In Africa, the majority of studies (82%; 9/11) were done in urban settings while 18% (2/11) were done in rural settings. Ten (91%) of the studies reported on patients suffering from respiratory tract infections and one study (9%) reported on patients suffering from gastroenteritis. In these studies, a total of 383 (10.4%) samples tested positive for HBoV (Table 3). More studies reported HBoV in children less than five years of age (54%; 6/11) compared to children above the age of 5 and adults 45% (5/11) (Table 3).

Countries that reported on HBoV in Africa included Kenya 18% (2/11), South Africa 36% (4/11), Egypt 18% (2/11), Cameroon 9% (1/11), and Senegal 18% (2/11). Five of the 11 studies in Africa focused on hospitalized patients and 36% (4/11) studies focused on outpatients, while 18% (2/11) studies focused on both hospitalized and outpatients. Eight (73%; 8/11) of the studies in Africa collected nasal swabs, two studies 18% (2/11) collected throat swabs, and one (9%; 1/11) study collected stool samples.

The prevalence of HBoV in Africa was 13% in individuals suffering from gastroenteritis with and without respiratory tract symptoms. The high detection rate of HBoV in Africa was consistent with the global increase of HBoV in children less than 5 years of age [4, 59]. Children of all age group are most likely to experience HBoV infection as a result of poor sanitation and hygiene practices [59]. The most predominant HBoV subtype identified in Africa was HBoV1, which was detected in all the studies. Only one study (9%), from Kenya detected all subtypes (HBoV1-4) from children of all age group (Table 3). Not all the studies tested for all HBoV subtypes; this may be due to the fact that other HBoV subtypes have just been recently discovered compared to HBoV1 [37]. The most predominant HBoV subtype identified in other developing countries was HBoV1, which was isolated in all the studies. Only 10% (1/10) of the studies from china detected HBoV2 in the study population (Table 2).

The results in Africa indicated that HBoV in children less than five years of age was high, 54% (6/11) compared to children above 5 years of age and adults 45% (5/11) (Table 3). Schildgen and colleagues [60] showed that all age groups can be affected by HBoV, although severe infections requiring hospitalization occur primarily in patients with an underlying disease and children under 5 years of age [61–64]. Severe clinical cases (such as destruction of the epithelium of the respiratory system) have been described in children [61, 64–66] and adults with immunodeficiency [64] and other risk groups [67]. Studies in Africa (13%; 9/70) were mostly done in urban setting compared to other developing countries/worldwide (87%; 61/70) (Tables 1, 2, and 3). This could be due to the lack of laboratory resource capacity and technology for the detection of HBoV in rural settings.

The methods used for detecting HBoV have been conventional PCR [17, 28, 40, 41, 45, 53, 64] and real-time PCR [42–45, 54, 68], due to the limited success of serological and viral culture techniques. Real-time PCR is more sensitive and offers greater sensitivity, increased specificity with the addition of oligoprobes, and the added benefit of a closed detection system, reducing the likelihood of false positive results due to contamination with amplicon [33]. In Africa, 63% (7/11) of studies used conventional PCR for detection, 27% (3/11) used real-time PCR, and 9% (1/11) used Multiplex PCR which is also conventional PCR (Table 3).

In all eleven African studies, HBoV1 was detected (Table 3), similarly in other developing countries HBoV1 was detected in all the studies. HBoV Subtype 1 is mainly associated with respiratory diseases but can also be found in stool samples from patients suffering from diarrhea. Previous studies have reported prevalence of HBoV in symptomatic patients 1.5–16% worldwide [69, 70]. Several studies have isolated HBoV from children with respiratory tract infection worldwide, and the prevalence of HBoV in these children was 1.5%–19% [32, 33, 35].

The reports on HBoV in Africa, other developing countries, and worldwide in individuals suffering from respiratory tract infection 78% (55/70) were higher compared to those suffering from gastroenteritis 21% (15/70) (Tables 1, 2, and 3). This could be due to the fact that most studies focused on HBoV in respiratory tract infection since its discovery in 2005 [28, 33, 36, 71]. However recent studies are increasingly detecting HBoV in individuals suffering from diarrheal diseases due to the presence of the virus in stool samples of individuals suffering from gastroenteritis [37, 72–74].

Although the number of studies in Africa is limited, the HBoV prevalence rate of 13% indicates that this virus is one of the emerging viral agents in those suffering from diarrhea with and without respiratory tract infections. Currently there is no available reporting system for HBoV infection in the primary healthcare systems in Africa, suggesting that diarrheal cases with and without respiratory tract infection are likely to be underreported [47]. The high frequency of HBoV in children raises a potential health risk as these children may act as reservoir for other emerging epidemic HBoV strains [27, 37, 75].

6. Conclusion

More studies are required in Africa, especially in rural settings to monitor the prevalence of HBoV and help understand the role of HBoV in individuals suffering from gastroenteritis with/without respiratory tract infection. HBoV infections are likely to be underreported in Africa considering the costs of testing for the virus. This review was done to shed light on HBoV and its possible role in diarrheal incidence.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the library staff members of the University of Venda who provided assistance for this review. This study was done through funding from the Director of Research and Innovation, University of Venda, Project no. SMNS/17/MBY/03.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health organization (WHO) http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs178/en/, 2014, Accessed 12.01.2016.

- 2.Liu L., Johnson H., Cousens S. Global, regional and national causes of child mortality: an update systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. The Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2151–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misigo D., Mwaengo D., Mburu D. Molecular detection and phylogenetic analysis of Kenyan human bocavirus isolates. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2014;8(2):221–227. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niang M. N., Dosseh A., Ndiaye K., et al. Sentinel surveillance for influenza in Senegal, 1996-2009. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;206(1):S129–S135. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arden K. E., Chang A. B., Lambert S. B., Nissen M. D., Sloots T. P., Mackay I. M. Newly identified respiratory viruses in children with asthma exacerbation not requiring admission to hospital. Journal of Medical Virology. 2010;82(8):1458–1461. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moors E., Singh T., Siderius C., Balakrishnan S., Mishra A. Climate change and waterborne diarrhoea in northern India: Impacts and adaptation strategies. Science of the Total Environment. 2013;468-469:S139–S151. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNICEF/WHO. Diarrhoea: Why Children Are Still Dying and What Can Be Done. New York, NY, USA: United Nations Children's Fund; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Moneim A. S., Kamel M. M., Hamed D. H., et al. A novel primer set for improved direct gene sequencing of human bocavirus genotype-1 from clinical samples. Journal of Virological Methods. 2016;228:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glass R. I., Noel J., Ando T., et al. The epidemiology of enteric caliciviruses from humans: a reassessment using new diagnostics. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000;181(supplement 2):S254–S261. doi: 10.1086/315588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bresee J. S., Duggan C., Glass R. I., King C. K. Managing acute gastroenteritis among children; oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. (RR16) 2003;52:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrant R. L., DeBoer M. D., Moore S. R., Scharf R. J., Lima A. A. The impoverished gut—a triple burden of diarrhoea, stunting and chronic disease. Nature reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Apr 2013;10(4):220–229. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulkow L. R., Singleton R. J., DeByle C., et al. Risk factors for hospitalization with lower respiratory tract infections in children in rural Alaska. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1220–e1227. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-García M. L., Calvo C., Pozo F., et al. Human bocavirus detection in nasopharyngeal aspirates of children without clinical symptoms of respiratory infection. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2008;27(4):358–360. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181626d2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vicente D., Cilla G., Montes M., Pérez-Yarza E. G., Pérez-Trallero E. Human bocavirus, a respiratory and enteric virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(4):636–637. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares C. C., Santos N., Beard R. S., et al. Norovirus detection and genotyping for children with gastroenteritis, Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(8):1244–1246. doi: 10.3201/eid1308.070300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volotão E. M., Scares C. C., Maranhão A. G., Rocha L. N., Hoshino Y., Santos N. Rotavirus surveillance in the city of Rio de Janeiro-Brazil during 2000-2004: Detection of unusual strains with G8F or G10P specifities. Journal of Medical Virology. 2006;78(2):263–272. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastien N., Brandt K., Dust K., Ward D., Li Y. Human bocavirus infection, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12(5):848–850. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.051424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan N. M., Dove W., Abu-Zeid A. F., Shamoon H. E., Abd-Eldayem S. A., Hart C. A. Human bocavirus infection among children, Jordan. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12(9):1418–1420. doi: 10.3201/eid1209.060417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindner J., Karalar L., Zehentmeier S., et al. Humoral immune response against human bocavirus VP2 virus-like particles. Viral Immunology. 2008;21(4):443–449. doi: 10.1089/vim.2008.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chieochansin T., Chutinimitkul S., Payungporn S., et al. Complete coding sequences and phylogenetic analysis of human bocavirus (HBoV) Virus Research. 2007;129(1):54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntosh K. Human bocavirus: developing evidence for pathogenicity. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;194(9):1197–1199. doi: 10.1086/508228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurda B. L., Parent K. N., Bladek H., et al. Human bocavirus capsid structure: Insights into the structural repertoire of the Parvoviridae. Journal of Virology. 2010;84(12):5880–5889. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02719-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z., Zheng Z., Luo H., et al. Human bocavirus NP1 inhibits IFN-β production by blocking association of IFN regulatory factor 3 with IFNB promoter. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;189(3):1144–1153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar A., Filippone C., Lahtinen A., et al. Comparison of th-cell immunity against human bocavirus and parvovirus b19: proliferation and cytokine responses are similar in magnitude but more closely interrelated with human bocavirus. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2011;73(2):135–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arthur J. L., Higgins G. D., Davidson G. P., Givney R. C., Ratcliff R. M. A novel bocavirus associated with acute gastroenteritis in Australian children. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5(4, article e1000391) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tozer S. J., Lambert S. B., Whiley D. M., et al. Detection of human bocavirus in respiratory, fecal, and blood samples by real-time PCR. Journal of Medical Virology. 2009;81(3):488–493. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kantola K., Sadeghi M., Antikainen J., et al. Real-time quantitative PCR detection of four human bocaviruses. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(11):4044–4050. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00686-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allander T., Tammi M. T., Eriksson M., Bjerkner A., Tiveljung-Lindell A., Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(36):12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao B., Yu X., Wang C., et al. High human bocavirus viral load is associated with disease severity in children under five years of age. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062318.e62318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maggi F., Andreoli E., Pifferi M., Meschi S., Rocchi J., Bendinelli M. Human bocavirus in Italian patients with respiratory diseases. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2007;38(4):321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissbrich B., Neske F., Schubert J., et al. Frequent detection of bocavirus DNA in German children with respiratory tract infections. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6, article no. 109 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng L.-S., Yuan X.-H., Xie Z.-P., et al. Human bocavirus infection in young children with acute respiratory tract infection in Lanzhou, China. Journal of Medical Virology. 2010;82(2):282–288. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chieochansin T., Thongmee C., Vimolket L., Theamboonlers A., Poovorawan Y. Human bocavirus infection in children with acute gastroenteritis and healthy controls. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;61(6):479–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma X., Endo R., Ishiguro N., et al. Detection of human Bocavirus in Japanese children with lower respiratory tract infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(3):1132–1134. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1132-1134.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chow B. D. W., Esper F. P. The human bocaviruses: a review and discussion of their role in infection. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 2009;29(4):695–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khamrin P., Malasao R., Chaimongkol N., et al. Circulating of human bocavirus 1, 2, 3, and 4 in pediatric patients with acute gastroenteritis in Thailand. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2012;12(3):565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jartti T., Söderlund-Venermo M., Allander T., Vuorinen T., Hedman K., Ruuskanen O. No efficacy of prednisolone in acute wheezing associated with human bocavirus infection. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011;30(6):521–523. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318216dd81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin Y., Cheng W.-X., Xu Z.-Q., et al. High prevalence of human bocavirus 2 and its role in childhood acute gastroenteritis in China. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2011;52(3):251–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnold J. C. Human bocavirus in children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2010;29(6):557–558. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181e0747d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arden K. E., McErlean P., Nissen M. D., Sloots T. P., Mackay I. M. Frequent detection of human rhinoviruses, paramyxoviruses, coronaviruses, and bocavirus during acute respiratory tract infections. Journal of Medical Virology. 2006;78(9):1232–1240. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kesebir D., Vazquez M., Weibel C., et al. Human bocavirus infection in young children in the United States: Molecular epidemiological profile and clinical characteristics of a newly emerging respiratory virus. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;194(9):1276–1282. doi: 10.1086/508213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allander T., Andreasson K., Gupta S., et al. Identification of a third human polyomavirus. Journal of Virology. 2007;81(8):4130–4136. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00028-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esposito S., Lizioli A., Lastrico A., et al. Impact on respiratory tract infections of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine administered at 3, 5 and 11 months of age. Respiratory Research. 2007;8, article no. 12 doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi E. H., Lee H. J., Kim S. J., et al. The association of newly identified respiratory viruses with lower respiratory tract infections in Korean children, 2000–2005. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43(5):585–592. doi: 10.1086/506350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manning A., Russell V., Eastick K., et al. Epidemiological profile and clinical associations of human bocavirus and other human parvoviruses. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;194(9):1283–1290. doi: 10.1086/508219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schildgen O., Qiu J., Sderlund-Venermo M. Genomic features of the human bocaviruses. Future Virology. 2012;7(1):31–39. doi: 10.2217/fvl.11.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hustedt J. W., Christie C., Hustedt M. M., Esposito D., Vazquez M. Seroepidemiology of human bocavirus infection in Jamaica. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038206.e38206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kapoor A., Hornig M., Asokan A., Williams B., Henriquez J. A., Lipkin W. I. Bocavirus episome in infected human tissue contains Non-Identical termini. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021362.e21362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen A. Y., Cheng F., Lou S., et al. Characterization of the gene expression profile of human bocavirus. Virology. 2010;403(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Regamey N., Frey U., Deffernez C., Latzin P., Kaiser L. Isolation of human bocavirus from Swiss infants with respiratory infections. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2007;26(2):177–179. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000250623.43107.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foulongne V., Olejnik Y., Perez V., Elaerts S., Rodière M., Segondy M. Human bocavirus in French children. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12(8):1251–1253. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.060213.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin F., Zeng A., Yang N., et al. Quantification of human bocavirus in lower respiratory tract infections in China. Infectious Agents and Cancer. 2007;2(1) doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sloots T. P., McErlean P., Speicher D. J., Arden K. E., Nissen M. D., Mackay I. M. Evidence of human coronavirus HKU1 and human bocavirus in Australian children. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2006;35(1):99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smuts H., Hardie D. Human bocavirus in hospitalized children, South Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12(9):1457–1458. doi: 10.3201/eid1209.051616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonzel L., Tenenbaum T., Schroten H., Schildgen O., Schweitzer-Krantz S., Adams O. Frequent detection of viral coinfection in children hospitalized with acute respiratory tract infection using a real-time polymerase chain reaction. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2008;27(7):589–594. doi: 10.1097/inf.0b013e3181694fb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization (WHO) Treatment of diarrhea: a manual for physicians and senior health workers. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications, 2005, Accessed 24 June 2015.

- 57.R Core Team. Programming language and free software environment for statistical computing and graphics (Statistical analysis) 2018.

- 58.Mobius T. Package "metagen", (statistical analysis package) 2015.

- 59.Symekher S. M., Gachara G., Simwa J. M., et al. Human bocavirus infection in children with acute respiratory infection in Nairobi, Kenya. Open Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2013;03(04):234–238. doi: 10.4236/ojmm.2013.34035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schildgen O. Human bocavirus: lessons learned to date. Pathogens. 2013;2(1):1–12. doi: 10.3390/pathogens2010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heydari H., Mamishi S., Khotaei G.-T., Moradi S. Fatal type 7 adenovirus associated with human bocavirus infection in a healthy child. Journal of Medical Virology. 2011;83(10):1762–1763. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Antunes H., Rodrigues H., Silva N., et al. Etiology of bronchiolitis in a hospitalized pediatric population: Prospective multicenter study. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2010;48(2):134–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Calvo C., García-García M. L., Pozo F., Carvajal O., Pérez-Breña P., Casas I. Clinical characteristics of human bocavirus infections compared with other respiratory viruses in Spanish children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2008;27(8):677–680. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31816be052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kupfer B., Vehreschild J., Cornely O., et al. Severe pneumonia and human bocavirus in adult. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;12(10):1614–1616. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Calvo J. C., Singh K. K., Spector S. A., Sawyer M. H. Human bocavirus: prevalence and clinical spectrum at a children's hospital. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43(3):283–288. doi: 10.1086/505399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martin E. T., Fairchok M. P., Kuypers J., et al. Frequent and prolonged shedding of bocavirus in young children attending daycare. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;201(11):1625–1632. doi: 10.1086/652405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Müller A., Klinkenberg D., Vehreschild J., et al. Low prevalence of human metapneumovirus and human bocavirus in adult immunocompromised high risk patients suspected to suffer from Pneumocystis pneumonia. Infection. 2009;58(3):227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qu X., Duan Z., Qi Z., et al. Human bocavirus infection, People’s Republic of China. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2007;13(1):150–152. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arnott A., Vong S., Rith S., et al. Human bocavirus amongst an all-ages population hospitalised with acute lower respiratory infections in Cambodia. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2013;7(2):201–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Do A. H. L., van Doorn H. R., Nghiem M. N., et al. Viral etiologies of acute respiratory infections among hospitalized vietnamese children in Ho Chi Minh City, 2004-2008. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018176.e18176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pham N. T. K., Trinh Q. D., Chan-It W., et al. Human bocavirus infection in children with acute gastroenteritis in Japan and Thailand. Journal of Medical Virology. 2011;83(2):286–290. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cashman O., O'Shea H. Detection of human bocaviruses 1, 2 and 3 in Irish children presenting with gastroenteritis. Archives of Virology. 2012;157(9):1767–1773. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koseki N., Teramoto S., Kaiho M., et al. Detection of human bocaviruses 1 to 4 from nasopharyngeal swab samples collected from patients with respiratory tract infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2012;50(6):2118–2121. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00098-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kapoor A., Simmonds P., Slikas E., et al. Human bocaviruses are highly diverse, dispersed, recombination prone, and prevalent in enteric infections. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;201(11):1633–1643. doi: 10.1086/652416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carrol E. D., Mankhambo L. A., Guiver M., et al. PCR improves diagnostic yield from lung aspiration in malawian children with radiologically confirmed pneumonia. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021042.e21042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moreno L., Eguizábal L., Ghietto L. M., Bujedo E., Adamo M. P. Human bocavirus respiratory infection in infants in Córdoba, Argentina. Archivos Argentinos de Pediatría. 2014;12(1):70–74. doi: 10.5546/aap.2014.eng.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Salmón-Mulanovich G., Sovero M., Laguna-Torres V. A., et al. Frequency of human bocavirus (HBoV) infection among children with febrile respiratory symptoms in Argentina, Nicaragua and Peru. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2011;5(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Sousa T. T., Souza M., Fiaccadori F. S., Borges A. M., da Costa P. S., Cardoso D. D. Human bocavirus 1 and 3 infection in children with acute gastroenteritis in Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107(6):800–804. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762012000600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Durigon G. S., Oliveira D. B. L., Vollet S. B., et al. Hospital-acquired human bocavirus in infants. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2010;76(2):171–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Proenca-Modena J. L., Paula F. E., Buzatto G. P., et al. Hypertrophic adenoid is a major infection site of human bocavirus 1. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014;52(8):3030–3037. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00870-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Proenca-Modena J. L., Pereira Valera F. C., Jacob M. G., et al. High rates of detection of respiratory viruses in tonsillar tissues from children with chronic adenotonsillar disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042136.e42136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Proença-Modena J. L., Gagliardi T. B., de Paula F. E., et al. Detection of human bocavirus mRNA in respiratory secretions correlates with high viral load and concurrent diarrhea. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021083.e21083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bezerra P. G. M., Britto M. C. A., Correia J. B., et al. Viral and atypical bacterial detection in acute respiratory infection in children under five years. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018928.e18928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Silva A. K., Santos M. C., Mello W. A., Sousa R. C. Ocurrence of human bocavirus associated with acute respiratory infections in children up to 2 years old in the city of belém, Pará State, Brazil. Revista Pan-Amazônica de Saúde. March 2010;1(1):87–92. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sentilhes A.-C., Choumlivong K., Celhay O., et al. Respiratory virus infections in hospitalized children and adults in Lao PDR. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2013;7(6):1070–1078. doi: 10.1111/irv.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kenmoe S., Tchendjou P., Vernet M.-A., et al. Viral etiology of severe acute respiratory infections in hospitalized children in Cameroon, 2011–2013. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2016;10(5):386–393. doi: 10.1111/irv.12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Feng L., Li Z., Zhao S., et al. Viral etiologies of hospitalized acute lower respiratory infection patients in China, 2009-2013. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099419.e99419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lau S. K. P., Yip C. C. Y., Que T.-L., et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of human bocavirus in respiratory and fecal samples from children in Hong Kong. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196(7):986–993. doi: 10.1086/521310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Song J.-R., Jin Y., Xie Z.-P., et al. Novel human bocavirus in children with acute respiratory tract infection. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2010;16(2):324–327. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.090553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen Y., Liu F., Wang C., et al. Molecular identification and epidemiological features of human adenoviruses associated with acute respiratory infections in hospitalized children in Southern China, 2012-2013. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155412.e0155412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang J., Xu Z., Niu P., et al. A two-tube multiplex reverse transcription PCR assay for simultaneous detection of viral and bacterial pathogens of infectious diarrhea. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:9. doi: 10.1155/2014/648520.648520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liao X., Hu Z., Liu W., et al. New epidemiological and clinical signatures of 18 pathogens from respiratory tract infections based on a 5-year study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9, article e0138684) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu W. K., Liu Q., De Chen H., et al. Epidemiology of acute respiratory infections in children in Guangzhou: A three-year study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096674.e96674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhou T., Chen Y., Chen J., et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of human bocavirus in children with acute gastroenteritis in Chengdu, West China, 2012-2013. Journal of Medical Virology. 2017;89(10):1743–1748. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El-Mosallamy W. A., Awadallah M. G., Abd El-Fattah M. D. Human bocavirus among viral causes of infantile gastroenteritis. The Egyptian Journal of Medical Microbiology. July 2015;24(3):53–59. doi: 10.12816/0024929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kantola K., Hedman L., Allander T., et al. Serodiagnosis of human bocavirus infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46(4):540–546. doi: 10.1086/526532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Salez N., Vabret A., Leruez-Ville M., et al. Evaluation of four commercial multiplex molecular tests for the diagnosis of acute respiratory infections. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130378.e0130378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Neske F., Blessing K., Tollmann F., et al. Real-time PCR for diagnosis of human bocavirus infections and phylogenetic analysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45(7):2116–2122. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00027-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lu X., Chittaganpitch M., Olsen S. J., et al. Real-time PCR assays for detection of bocavirus in human specimens. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(9):3231–3235. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00889-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shokrollahi M. R., Noorbakhsh S., Monavari H. R., Darestani S. G., Motlagh A. V., Nia S. J. Acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis in hospitalized children: a cross sectional study. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology. 2014;7(12) doi: 10.5812/jjm.11840.e11840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Monavari S. H., Noorbakhsh S., Mollaie H., Fazlalipour M., Kiasari B. A. Human Bocavirus in Iranian children with acute gastroenteritis. Medical Journal of The Islamic Republic of Iran. 2013;27(3):127–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goktas S., Sirin M. C. Prevalence and seasonal distribution of respiratory viruses during the 2014 - 2015 season in Istanbul. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology. 2016;9(9):1232–1240. doi: 10.5812/jjm.39132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gerna G., Piralla A., Campanini G., Marchi A., Stronati M., Rovida F. The human bocavirus role in acute respiratory tract infections of pediatric patients as defined by viral load quantification. Microbiologica-Quarterly Journal of Microbiological Sciences. 2007;30(4):383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pierangeli A., Scagnolari C., Trombetti S., et al. Human bocavirus infection in hospitalized children in Italy. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 2008;2(5):175–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2008.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rovida F., Campanini G., Piralla A., Adzasehoun K. M. G., Sarasini A., Baldanti F. Molecular detection of gastrointestinal viral infections in hospitalized patients. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2013;77(3):231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Narayanan H., Sankar S., Simoes E. A. F., Nandagopal B., Sridharan G. Molecular detection of human metapneumovirus and human bocavirus on oropharyngeal swabs collected from young children with acute respiratory tract infections from rural and peri-urban communities in South India. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy. 2013;17(2):107–115. doi: 10.1007/s40291-013-0030-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Al-Rousan H. O., Meqdam M. M., Alkhateeb A., Al-Shorman A., Qaisy L. M., Al-Moqbel M. S. Human bocavirus in Jordan: Prevalence and clinical symptoms in hospitalised paediatric patients and molecular virus characterisation. Singapore Medical Journal. 2011;52(5):365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kaplan N. M., Dove W., Abd-Eldayem S. A., Abu-Zeid A. F., Shamoon H. E., Hart C. A. Molecular epidemiology and disease severity of respiratory syncytial virus in relation to other potential pathogens in children hospitalized with acute respiratory infection in Jordan. Journal of Medical Virology. 2008;80(1):168–174. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Moriyama Y., Hamada H., Okada M., et al. Distinctive clinical features of human bocavirus in children younger than 2 years. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;169(9):1087–1092. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1183-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nawaz S., Allen D. J., Aladin F., Gallimore C., Iturriza-Gómara M. Human bocaviruses are not significantly associated with gastroenteritis: Results of retesting archive DNA from a case control study in the UK. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041346.e41346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Etemadi M. R., Azizi Jalilian F., Abd Wahab N., et al. First detected human bocavirus in a Malaysian child with pneumonia and pre-existing asthma: A case report. Medical Journal of Malaysia. 2012;67(4):433–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Montenij M., Moll H., Berger M., Niesters B. Human bocavirus in febrile children consulting a GP service in the Netherlands. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2006;43(5):585–592. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kapoor A., Slikas E., Simmonds P., et al. A newly identified bocavirus species in human stool. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;199(2):196–200. doi: 10.1086/595831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Suzuki A., Lupisan S., Furuse Y., et al. Respiratory viruses from hospitalized children with severe pneumonia in the Philippines. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2012;12, article no. 267 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dia N., Richard V., Kiori D., et al. Respiratory viruses associated with patients older than 50 years presenting with ILI in Senegal, 2009 to 2011. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(1, article no. 189):3–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nunes M. C., Kuschner Z., Rabede Z., et al. Clinical epidemiology of bocavirus, rhinovirus, two polyomaviruses and four coronaviruses in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected South African children. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086448.e86448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Smuts H., Workman L., Zar H. J. Role of human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus NL63 and human bocavirus in infants and young children with acute wheezing. Journal of Medical Virology. 2008;80(5):906–912. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Madhi S. A., Govender N., Dayal K., et al. Bacterial and respiratory viral interactions in the etiology of acute otitis media in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected South African Children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2015;34(7):753–760. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chuang C.-Y., Kao C.-L., Huang L.-M., et al. Human bocavirus as an important cause of respiratory tract infection in Taiwanese children. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2011;44(5):323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ziyade N., Şirin G., Elgörmüş N., Daş T. Detection of human bocavirus DNA by multiplex PCR analysis: Postmortem case report. Balkan Medical Journal. 2015;32(2):226–229. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.15254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.da Silva E. R., Pitrez M. C. P., Arruda E., et al. Severe lower respiratory tract infection in infants and toddlers from a non-affluent population: viral etiology and co-detection as risk factors. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2013;13(1, article 41) doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]