Abstract

Context:

Music therapy is a nonpharmacological modality which can provide promising results for postcesarean section recovery.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of two types of intraoperative meditation music with control group on postcesarean section pain, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, and psychological maternal wellbeing.

Settings and Design:

A prospective, randomized, controlled study was conducted on 189 patients.

Patients and Methods:

The inclusion criteria were the American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classes 1E and 2E women aged over 18 years posted for emergency cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. The exclusion criteria were patients with hearing/ear abnormalities and psychiatric disorders. Patients were randomly allocated into three groups – soothing meditation music (M) group, binaural beat meditation music (B) group, and control (C) group – where no music was played. After intervention, data were collected and statistically analyzed.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Student's t-test was applied for calculation of normative distribution and Mann–Whitney U-test for nonnormative distribution. Nominal categorical data between the groups were compared using Chi-squared test. P <0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results:

Both intraoperative meditation music groups had statistically significant less postoperative pain and anxiety and a better overall psychological wellbeing as compared to the control. There was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence and severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting across all three groups.

Conclusions:

Intraoperative meditation music as good adjunct to spinal anesthesia can improve a cesarean section patient's postoperative experience by reducing postoperative pain, anxiety, and psychological wellbeing.

Keywords: Anxiety, meditation, music therapy, music, nausea, pain, postoperative, vomiting

INTRODUCTION

The most common and distressing symptoms which follow anesthesia and surgery, are pain and emesis. Pregnant women and those with recent intake of food as in emergency cesarean section are more likely to suffer from postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). It has been reported that despite the widespread use of opioid analgesics in the postoperative period, the overall incidence of moderate-to-severe pain following cesarean section is 30%.[1] Accordingly, the concept of preemptive analgesia has been introduced for postoperative pain control. Several pharmacological therapies have been employed as a part of preemptive analgesia, with varied results.[2] The search for a newer therapy which can minimize the postoperative pain, nausea, and vomiting continues to be a recurring challenge for research in the field of obstetric anesthesia. In this context, the role of nonpharmacological therapies assumes importance. Music as therapy has been in vogue since the ancient times. The Vedas mention the utilities of mantras during childbirth. Charaka in his writings has highlighted the importance of bhajanas on recovery from surgery. Acupuncture, therapeutic suggestions, and transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation are some other nonpharmacological methods which have been used.

Music consists of “a complex web of expressively organized sounds” and includes the basic elements of tone, duration, loudness, and pitch.[3] Music is a noninvasive, safe, and inexpensive intervention that can be delivered easily and successfully. The use of music or music with therapeutic suggestions intraoperatively has produced positive results in some studies. The different types of meditation music include classical music, with different classical tunes, primordial sounds (e.g., “Om”), nature sounds like those in a garden or a forest or a hilltop, instrumental music from instruments such as the classical guitar, violin, sitar, piano, harp, flute, Sufi music, and Christian music with a blend of traditional Christian tunes and soft instrumental music. With this background, we conducted a study to determine if meditation music (soothing binaural) as a nonpharmacological adjunct to standard care can decrease postoperative pain, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, and the overall psychological wellbeing of a surgical patient.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This prospective, randomized, controlled study was conducted from July 2016 to April 2017 at a tertiary care hospital on 189 parturients undergoing emergency cesarean section delivery under spinal anesthesia after obtaining ethical committee clearance and written informed patient consent. The inclusion criteria included women who were aged over 18 years posted for emergency cesarean section delivery, who were willing to participate in the study and had signed an informed written consent form with the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Classes 1E and 2E. The exclusion criteria were women with hearing defects or any ear abnormalities and women with psychiatric disorders.

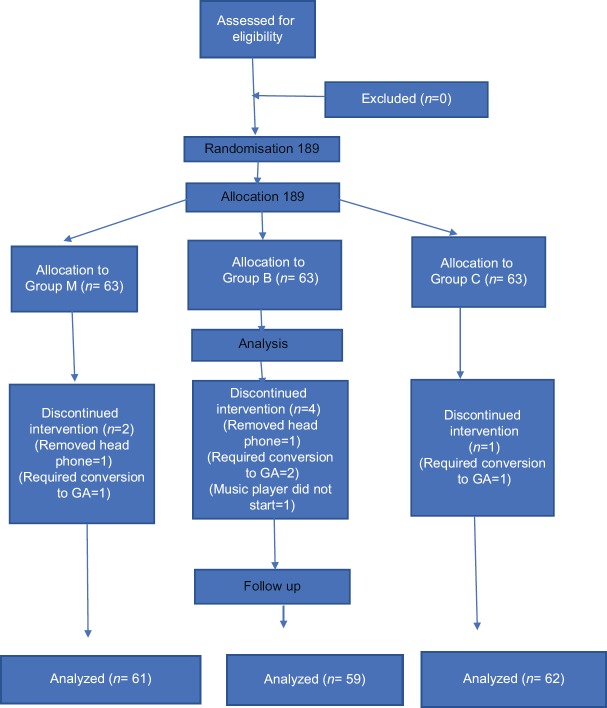

After referring to a study by Chang and Chen[4] for visual analog scale (VAS) for anxiety scores outcome and assuming similar outcomes, we calculated a sample size of 63 patients in each group with a total of 189 patients that would permit a confidence interval of 95% and a power of 70%. Our primary objective was to assess the effectiveness of two types of intraoperative meditation music – soothing and binaural beat music on overall maternal clinical and psychological wellbeing and compare these methods with placebo for the same. The secondary objective was to compare the effectiveness of the above two types of intraoperative meditation music with placebo in reducing postoperative pain, anxiety, and the severity of postoperative nausea vomiting at 1, 6, and 24 h. Patients were randomly allocated into three groups; two intervention groups – soothing meditation music group or M group and binaural beat meditation music group or B group and the control group or C group – where no music was played. After intervention, data were collected and statistically analyzed. The randomization into three groups was done, just before taking the patient on the operation theater table by means of picking up of chits by the patient marked as M, B, and C kept in a box [Figure 1]. There were a total of 189 chits in the box, with equal number of M, B, and C chits (63 each). The patient who picked M chit was assigned to M group who then listened to meditation music adjudged to be calming and soothing from an MP3 player through bilateral headphones that covered the whole ear, so that no other sounds from the operation room would interfere in the study. In a similar way, the patient who picked up B chit was assigned to B group; she then listened to binaural beat meditation music from an MP3 player through bilateral headphones that covered the whole ear so that no other sounds from the operation room would interfere in the study. The patient who picked up C chit was assigned to C group who then listened to a blank MP3 player through bilateral headphones that covered the whole ear. Under aseptic precautions and the patients in sitting or left lateral position, parts were painted and draped. L3-L4 or L4-L5 space was identified. A 25G Quincke's spinal needle was inserted into the subarachnoid space, confirmed by clear and free flow of cerebrospinal fluid. 1.8 to 2.0 mL of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine was injected and the patient was put on supine position and oxygen face mask at 6 L/min.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram

The headphones were then applied, and music played/not played according to the patient's group and continued until skin closure and dressing.

Routine monitoring such as pulse rate, respiratory rate, noninvasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and electrocardiography were done as per the standard practice.

If there was more than 20% fall in blood pressure, injection mephenteramine 6 mg was given intravenously (i.v.). After the baby was delivered, 10 units of oxytocin was given by i.v. infusion.

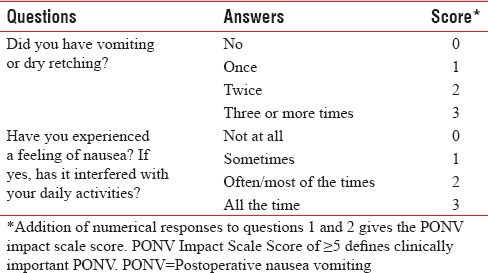

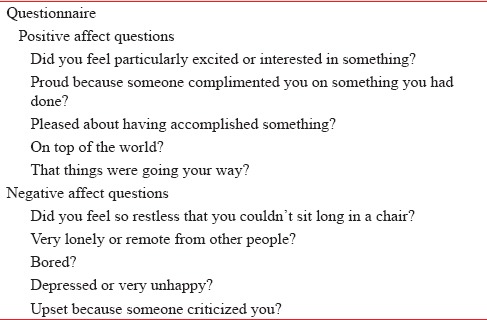

Earphones were removed at the end of the procedure after skin closure and dressing. We recorded the intensity of pain (pain score), intensity of anxiety (anxiety score), PONV score and psychological wellbeing at 1, 6 and 24 h postoperatively after the surgery. The intensity of pain was estimated by the VAS where – 0 –represents no pain and 10 maximum possible pain. The intensity of anxiety was estimated by using the VAS where – 0-represents very calm and 10-very anxious. PONV was estimated by using the PONV impact scale [Table 1]. The psychological wellbeing was evaluated by an objective questionnaire [Table 2]. For positive affect, participants received 1 point for every “Yes” that they replied in the answers to the questions. The total points scored for positive affect questions was taken as the positive affect score. For negative affect, participants received 1 point for every “Yes” that they replied. The total points scored for negative affect questions was taken as the negative affect score. The overall “balance” score was created by subtracting the negative affect score from the positive affect score.

Table 1.

Postoperative nausea vomiting impact scale score

Table 2.

Psychological wellbeing questionnaire and score

Postoperatively, whenever patient requested for analgesia or when VAS score for pain was >3 (whichever was first), intramuscular diclofenac 75 mg was injected.

Whenever the patient complained of nausea vomiting or when PONV score was above 5, both intraoperative or postoperative up to 24 h, injection metoclopramide 10 mg was administered i.v. The time and dosage of giving analgesic and anti-emetic were recorded.

In the statistical analysis, continuous variables were presented as mean. Student's t-test was applied for calculation of statistical significance whenever the data followed normative distribution. Mann–Whitney U-test was applied whenever data followed nonnormative distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Nominal categorical data between the groups were compared using Chi-squared test. P < 0.05 was taken to indicate a statistically significant difference. Minitab version 17 was used for computation of statistics.

RESULTS

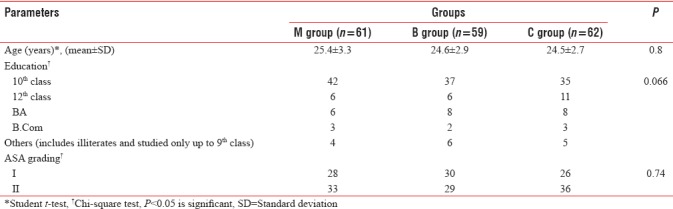

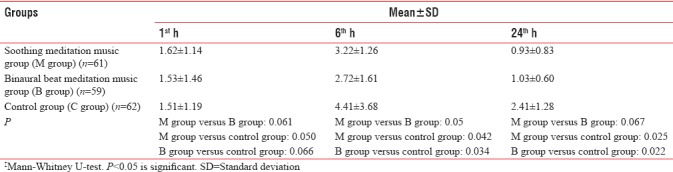

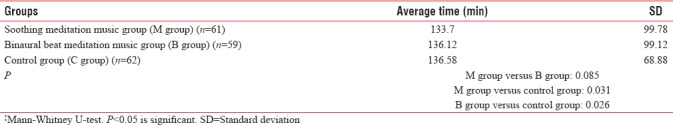

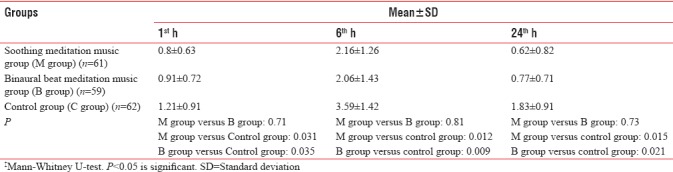

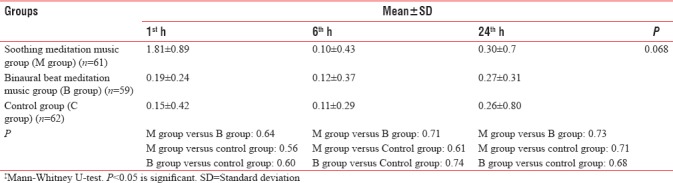

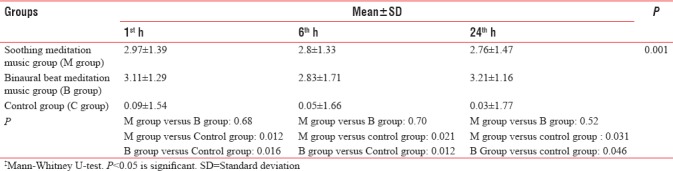

Removal of headphones was seen in two patients (one each in M and B groups); four patients were converted to general anesthesia (one in M, two in B and one in C group) and in one patient of B group, the music system failed to start. Thus, there were a total of 7 dropouts in our study. There were no statistically significant differences in the demographic profiles of the patients which included age, ASA physical status and educational background [Table 3]. The mean pain scores of M and B groups were statistically comparable at 1st, 6th and 24th h, while the mean pain scores of M and B groups compared with C group differed significantly at the 6th and 24th h [Table 4]. The mean time required for the 1st rescue analgesic in M and B groups were statistically comparable, whereas the mean time required for the 1st rescue analgesic in M and B groups compared with C group differed significantly [Table 5]. The mean anxiety scores (VAS) of M and B groups were statistically comparable at the 1st, 6th, and 24th h and the mean anxiety scores (VAS) in M and B groups compared with C group differed significantly at the 1st, 6th, and 24th h [Table 6]. The mean PONV scores in M, B, and C groups were statistically comparable at 1st, 6th, and 24th h [Table 7]. The mean psychological wellbeing scores in M and B groups were statistically comparable at the 1st, 6th, and 24th h and the mean psychological wellbeing scores in M and B groups compared with C group differed significantly at 1st, 6th, and 24th h [Table 8].

Table 3.

Patient demographics

Table 4.

Mean pain scores‡

Table 5.

Mean time required for first rescue analgesic‡

Table 6.

Mean anxiety scores‡ (visual analog scale)

Table 7.

Mean postoperative nausea vomiting Impact Scale score‡

Table 8.

Mean psychological wellbeing scale score‡

DISCUSSION

Every music has its own physical characteristics and hence produces unique physiological effects. Several studies have studied the impact of a particular type of music on surgical periods. A few studies have been conducted to compare the impact of different types of music on peri-cesarean section patients. In these studies, meditation music, classical music, rap music, jazz, therapeutic suggestions alone and in combination with music have been tried. Soothing meditation music stimuli processed by and through the brain can have a positive effect on neural and hormonal activity including emotional responses.[5] Soothing music stimulates the production of impulses and biochemical substances within the brain via the limbic system.[6] Binaural beat meditation music has long been of interest for a wide range of applications. Several studies have suggested that binaural beat music can be used for anxiolysis and mood improvement. There have been no studies on binaural beat music in cesarean section patients. Ours is the first study to compare the effects of meditation music and binaural beat music for the improvement of postoperative outcomes in cesarean section patients.

Monaural and binaural beats are generated when sine waves of neighboring frequencies and with stable amplitudes are presented to either both ears simultaneously (monaural beats) or to each ear separately (binaural beats).[7] Binaural beats are generated when the sine waves within a close range are presented to each ear separately. For example, when the 400 Hz tone is presented to the left ear and the 440 Hz tone to the right, a beat of 40 Hz is perceived, which appears subjectively to be located “inside” the head.[8] The binaural beat percept is the result of the effect of a central interaction occurring in the superior olivary nuclei.[9] Studies reporting significant effects on the continuous EEG after application of binaural beats have shown changes in certain frequency bands such as alpha and gamma.[10] A study on the effect of binaural beat frequencies (15 and 7 Hz) on meditation practice reported significant entrainment effects.[11]

Some authors found that binaural beat embedded audio in patients undergoing cataract surgery under local anesthesia decreased anxiety levels, heart rate, and the systolic blood pressure.[12] Some other authors have found that binaural beat audio decreased acute preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing ambulatory surgery.[8] A pilot study has shown that theta binaural beat reduced perceived pain severity in patients with chronic pain.[13] The researchers in a study found that binaural beat stimulation across the alpha range has an analgesic effect on acute laser pain in humans.[14] Our study cases, too, showed a decrease in postoperative anxiety levels and pain with intraoperative binaural beat audio. Some authors have studied the effects of music on pain intensity and pain distress on the 1st and 2nd postoperative days in abdominal surgery patients and the long-term effects of music on the 3rd postoperative day. They observed that, in the music group, the patient's pain intensity and pain distress in bed rest, during deep breathing and in shifting position were significantly lower on the 2nd postoperative day compared with control group of patients. On the 3rd postoperative day, when long-term effects of music on pain intensity and pain distress were assessed, there were significant differences between music and control groups.[15] Our study findings confirm with the findings of this study. We observed a decrease in postoperative pain scores at 6 and 24 h in both types of meditation music groups as compared to control; nevertheless, our study did not involve the 2nd and 3rd postoperative days. In a study on the effects of music therapy on women's anxiety during cesarean delivery, it was found that compared to the control group the music group had significantly lower anxiety and a higher level of satisfaction regarding the cesarean experience.[4] The findings of our study thus agree with the findings of this study; however, we did not measure intraoperative anxiety. In another study, the researchers sought to evaluate the effects of perioperative music intervention on pain in women with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy. They found that the postoperative anxiety score at the time of discharge from postanesthesia care unit for the control group was increased by a mean of 7.7, whereas the anxiety score for the music group decreased by 10.8.[16] This was similar to our study findings.

A study tried to examine the effect of synchronized sounds on anesthetic and hypnotic depth and found that synchronized music had no effect on the occurrence of anxiety.[17] These observations are a contradiction to our study findings. Phase synchronization occurs when oscillations in two brain regions have a constant phase relation over some time period. Phase synchronization is integral to cognition as it supports the processes of neural communication, neuroplasticity, and memory formation. If auditory beats do induce phase synchronization, this may indicate a role for monaural and binaural beats in modulating memory process. Recent findings based on intracranial electroencephalography (EEG) recordings in humans suggest that auditory beats can specifically alter not only EEG power but also phase synchronization.

In a study, the authors found that PONV at 1 h was reduced with intraoperative meditation music therapy; nevertheless, in contradiction to this, our study results did not show any difference in PONV at 1 h and the incidence of PONV was similar in all the three groups. However, like in our study, there was no difference in PONV at 6 and 24 h in their study. They used therapeutic suggestions in addition to meditation music in one of the groups and their study did not involve binaural beats as in our study.[18]

Studies by some authors in patients who underwent cesarean section and mastectomy surgeries under general anesthesia have shown that intraoperative soothing meditation music provided improved overall postoperative psychological wellbeing of the patients;[16,18] however unlike in our study, their study patients underwent surgery under general anesthesia. The reason why an intraoperative intervention like music led to postoperative improvement in parameters is something which everyone would like to know. Intraoperative music probably led to an improvement in the intraoperative psychological status of patients leading to a positive frame of mind so that she would feel less pain and require less antiemetic. This psychological wellbeing and decrease in neurohormonal stress response due to music probably extended into the postoperative period. Our study has some limitations. We could not do the blinding of patients and the observer. There was no choice in the type of music offered to the patients. In the intervention groups (M and B groups), mothers were not able to listen to the baby's cry. The baby's first cries are supposed to be soothing to the mother. In the intervention groups (M and B groups), communication with mothers by doctors during surgery was not possible. Our study did not include the monitoring of hemodynamic parameters intraoperative and postoperative. Music has been found to lower systolic blood pressure and heart rates by lowering perioperative stress; nevertheless, during the conduct of cases in the current study, we did observe a fall in the preoperative heart rates and systolic blood pressures intraoperatively with the onset of meditation music.

CONCLUSIONS

Intraoperative meditation music-both soothing and binaural beat is effective in improving the overall psychological wellbeing of mothers postoperatively and reducing postoperative pain and anxiety up to 24 h. There is no effect of intraoperative meditation music on the occurrence and severity of PONV.

We conclude that music is a good and simple option to improve a patient's perioperative experience. It can be a simple solution to incorporate in routine perioperative setups. We recommend further studies exploring the perioperative effect of other types of music on the mother and on psychological relaxation in the newborn.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dolin SJ, Cashman JN, Bland JM. Effectiveness of acute postoperative pain management: I. Evidence from published data. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:409–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garimella V, Cellini C. Postoperative pain control. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2013;26:191–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myskja A, Lindbaek M. Examples of the use of music in clinical medicine. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2000;120:1186–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang SC, Chen CH. Effects of music therapy on women's physiologic measures, anxiety, and satisfaction during cesarean delivery. Res Nurs Health. 2005;28:453–61. doi: 10.1002/nur.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneck CM. Occupational Therapy for Children. In: Case-Smith J, O’Brien J, editors. Visual perception. 6th ed. The United States of America: Elsevier Mosby; 2010. pp. 373–403. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krout RE. Music listening to facilitate relaxation and promote wellness: Integrated aspects of our neurophysiological responses to music. Arts Psychother. 2007;34:134–41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortiz T, Martínez AM, Fernández A, Maestu F, Campo P, Hornero R, et al. Impact of auditory stimulation at a frequency of 5 hz in verbal memory. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2008;36:307–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padmanabhan R, Hildreth AJ, Laws D. A prospective, randomised, controlled study examining binaural beat audio and pre-operative anxiety in patients undergoing general anaesthesia for day case surgery. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:874–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuriki S, Yokosawa K, Takahashi M. Neural representation of scale illusion: Magnetoencephalographic study on the auditory illusion induced by distinctive tone sequences in the two ears. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vernon D, Peryer G, Louch J, Shaw M. Tracking EEG changes in response to alpha and beta binaural beats. Int J Psychophysiol. 2014;93:134–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavallee CF, Koren SA, Persinger MA. A quantitative electroencephalographic study of meditation and binaural beat entrainment. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17:351–5. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiwatwongwana D, Vichitvejpaisal P, Thaikruea L, Klaphajone J, Tantong A, Wiwatwongwana A. The effect of music with and without binaural beat audio on operative anxiety in patients undergoing cataract surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Eye (Lond) 2016;30:1407–14. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zampi DD. Efficacy of theta binaural beats for the treatment of chronic pain. Altern Ther Health Med. 2016;22:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecsy K, Jones AK, Brown CA. Alpha-range visual and auditory stimulation reduces the perception of pain. Eur J Pain. 2017;21:562–72. doi: 10.1002/ejp.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaajoki A, Pietilä AM, Kankkunen P, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. Effects of listening to music on pain intensity and pain distress after surgery: An intervention. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:708–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binns-Turner PG, Wilson LL, Pryor ER, Boyd GL, Prickett CA. Perioperative music and its effects on anxiety, hemodynamics, and pain in women undergoing mastectomy. AANA J. 2011;79:S21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dabu-Bondoc S, Drummond-Lewis J, Gaal D, McGinn M, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Kain ZN, et al. Hemispheric synchronized sounds and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:772–5. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000076145.83783.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jayaraman L, Sharma S, Sethi N, Sood J, Kumra VP. Does intraoperative music therapy or positive therapeutic suggestions during general anaesthesia affect the postoperative outcome.– A double blind randomised controlled trial? Indian J Anaesth. 2006;50:258–61. [Google Scholar]