Abstract

Background:

In patients undergoing laparoscopic surgeries, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a serious concern. With an incidence of 46%–72%, PONV hampers the postoperative recovery in spite of the availability of many antiemetic drugs. The purpose of this study was to prospectively evaluate the efficacy of palonosetron and granisetron for the prevention of PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic abdominal surgery.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the efficacy of palonosetron and granisetron in preventing PONV and to compare the duration of action and side effects in patients undergoing laparoscopic abdominal surgery under general anesthesia.

Settings and Design:

Eighty patients who were comparable in all aspects were considered for this study. After their consent, they participated in this prospective, randomized, double-blinded, comparative study.

Materials and Methods:

In this observational study, 80 patients of either gender who were undergoing laparoscopic abdominal surgery under general anesthesia were enrolled in the study. Based on computer randomization, these patients were divided equally into two groups of 40 patients each in double-blinded manner. The treatments were given intravenously 5 min before induction of anesthesia. The episodes of PONV, severity of nausea/vomiting, and side effects were observed during the first 48 h after surgery.

Statistical Tests:

At the end of study, results were compiled and SPSS® statistical package version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two independent samples t-test was used for quantitative data, and Chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used for qualitative data. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results:

The incidence of PONV during 0–2 h in the postoperative period was 15% with palonosetron and 27.5% with granisetron; the incidence during 2–24 h postoperatively was 20% with palonosetron and 30% with granisetron. Both palonosetron and granisetron had comparable effectiveness as antiemetic during the early postoperative periods (0–24 h). During 24–48 h, the incidence was 17.5% and 37.5%, respectively (P = 0.04). Safety profile was similar in both the groups (P = 0.6).

Conclusion:

There were no significant differences in the overall incidence of PONV and complete responders for palonosetron and granisetron group in the early recovery period. However, due to its prolonged duration of action, palonosetron was more effective than granisetron for long-term prevention of PONV after laparoscopic abdominal surgery.

Keywords: 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor antagonist, granisetron, laparoscopic abdominal surgery, laparoscopy, palonosetron, postoperative nausea and vomiting

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic surgeries are rapidly emerging as preferred surgical procedures these days. These have considerably decreased the surgical mortality. For symptomatic cholelithiasis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is rapidly emerging as an alternative to open cholecystectomy.[1] It is the most preferred procedure for symptomatic cholelithiasis because of less morbidity and mortality associated with it. However, advantages of LC may be counteracted by a high incidence of distressing side effects such as postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). PONV is defined as nausea and/or vomiting occurring within 24 h after surgery. Patient characteristics, type of surgical procedure, duration of anesthesia, and surgery are few of the important determinants for risk of PONV. PONV can lead to delay in recovery, wound dehiscence, and prolonged hospitalization. Its prevalence has been reported in different studies about 44%–83%.[2,3] The incidence following LC is as high as 46%–72%.[4,5]

The etiology of PONV is not still clear, but it is probably a multifactorial phenomenon.[6,7] During laparoscopy, gas entrance into the abdominal cavity can cause increased pressure of peritoneal cavity which may lead to PONV.[8] Prolonged CO2 pneumoperitoneum can lead to peritoneal distention and diaphragmatic stimulation. It leads to stretching of mechanoreceptors, increased serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) synthesis and PONV. Intra-abdominal manipulation is one of the causes of PONV.[6,7]

One of the first-line therapeutic agents for the prevention of PONV is serotonin 5-HT type 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists. Because of their good efficacy and minimal side effects, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are most widely used antiemetic.[8] Palonosetron is the latest entrant in this 5-HT3 receptor antagonist group. It has a higher receptor-binding affinity and a longer plasma half-life than older 5-HT3 receptor antagonist such as ondansetron, granisetron, dolasetron, and ramosetron. Palonosetron shows allosteric binding and positive cooperativity which triggers receptor internalization. This results into persistent inhibition of 5-HT3 receptor function and long duration of action.[9,10,11] Some studies reported that palonosetron was more effective than ondansetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV)[12] and PONV.[13] Granisetron selectively blocks the 5-HT3 receptor with a relatively short half-life of 4–9 h. Granisetron is a potent and highly selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist that has little or no affinity for other 5-HT receptors or dopaminergic, adrenergic, benzodiazepine, histaminic, or opioid receptors.[14] In contrast, other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have affinities for various receptor-binding sites. Although not proven, the binding of these agents to additional receptor subtypes other than their target receptor may underlie the inferior adverse event profile seen with ondansetron compared with granisetron.[15,16] We hypothesized that long-acting palonosetron treatment would be more effective in lowering the incidence of PONV, compared to treatment with granisetron. The purpose of this study was to prospectively evaluate the efficacy of palonosetron and granisetron in the prevention of PONV in patients undergoing laparoscopic abdominal surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

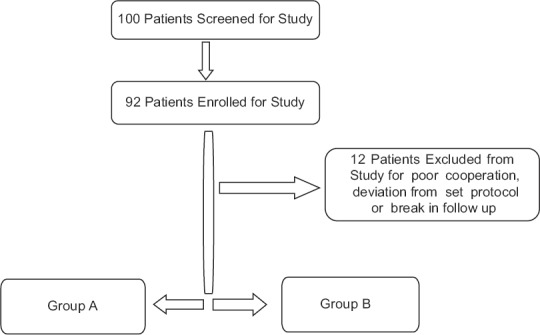

The study proposal was finalized and approved by the institution ethical committee before the investigation was initiated. This study enrolled 80 patients scheduled for elective laparoscopic abdominal surgery under general anesthesia. They ranged in the age group from 20 to 60 years (mean = 46 years). Written informed consent was acquired from all participants before enrollment in the study. This investigator-initiated, prospective, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial was performed at a tertiary care hospital between November 2012 and November 2014. Through a computer-generated randomization schedule, patients were randomly allocated into two groups to receive palonosetron (n = 40) or granisetron (n = 40) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Patient selection and distribution

Exclusion criteria were as follows: allergy to any of the experimental drugs, opioid dependence, a history of PONV and motion sickness, use of antiemetic medication within 24 h before surgery, pregnancy, inability to comprehend the 10 cm visual analog scales (VASs; 0 – none; 10 – maximum) for pain and nausea assessment, and unwillingness to be enrolled in the study. Furthermore, those who had received cancer chemotherapy within 4 weeks or emetogenic radiotherapy within 8 weeks before study entry and patients with ongoing vomiting from gastrointestinal disease were also excluded from the study.

The patients were allocated randomly into two groups with the help of computer-generated random number table. Patients of Group A were given palonosetron 0.075 mg and patients of Group B were given granisetron 2 mg intravenously (IV) along with premedication, immediately before induction of general anesthesia. Normal saline was added to bring the total injectable volume to 2.5 ml in each group. Two theater assistants were used to enroll the patients in groups and to prepare the study drugs. However, both were unaware of the study protocol and were not involved in the study for any further evaluation of patients.

The patients were kept fasting for 8 h and received tablet alprazolam 0.25 mg orally as premedication. Intraoperative monitoring consisted of electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure, and oxygen saturation (SpO2). Baseline vital parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded. After securing the intravenous line, patients were premedicated with injection rabeprazole 20 mg IV and injection midazolam 1 mg IV. With the help of facemask, preoxygenation with 100% oxygen (O2) was done. After pretreatment with the study drugs, anesthesia was induced with propofol 2 mg/kg body weight and maintained with oxygen and nitrous oxide mixture (50:50). Injection atracurium besylate 0.5 mg/kg body weight was used to facilitate endotracheal intubation. Isoflurane (0.7–1.3 MAC) and injection atracurium besylate 0.1 mg/kg body weight was used as a muscle relaxant. After induction, nasogastric tube was inserted and suction was applied to empty the stomach. Positive pressure ventilation was delivered with tidal volume and respiratory rate adjusted to maintain end-tidal CO2 between 30 and 40 mm of mercury (mmHg). The intra-abdominal pressure was maintained between 10 and 12 mmHg throughout the surgery with the help of CO2. Ropivacaine 0.2% was infiltrated at each surgical port before skin closure for postoperative analgesia. In addition, injection, tramadol HCl2 mg/kg body weight and injection paracetamol 20 mg/kg body weight was administered IV for intraoperative analgesia. During surgery, ringer lactate was infused in accordance with maintenance of volume requirements. Glycopyrrolate 10 mg/kg IV and neostigmine 50 mg/kg were used for reversal of residual neuromuscular blockade. The nasogastric tube was suctioned again and then removed before tracheal extubation. The total duration of CO2 insufflation, duration of surgery, and the total volume of fluid administered during surgery were recorded.

Postoperatively, all patients were observed by dedicated resident doctors who were unaware of the study drug. Nausea was defined as a subjectively unpleasant sensation associated with the urge to vomit. Incidences of vomiting included retching (defined as the labored, spastic, rhythmic contraction of the respiratory muscles without expulsion of the gastric contents) and actual vomiting (defined as the forceful expulsion of gastric contents from the mouth). A complete response to palonosetron and granisetron was defined as an absence of PONV and no need for further rescue antiemetic drugs. All data were collected for 0–2 h in postanesthesia care unit and from 2 to 48 h in postoperative ward. All patients were observed postoperatively for 48 h (divided into intervals, i.e. 0–2, 2–6, 6–24, and 24–48 h) for number of episodes of nausea, retching, and vomiting and side effects of the study drugs. Time to the first rescue antiemetic (metoclopramide 10 mg IV) was also noted in each group. Nausea was assessed using VAS (0–10, 0 = no nausea and 10 = worst possible nausea). A score of >5 was considered severe, 5 = moderate, and <5= mild nausea. The vomiting episodes of >2 were considered as severe, 2 as moderate, and <2 as mild. Rescue antiemetic metoclopramide 10 mg IV was given for moderate and severe nausea or vomiting episode. Patients were monitored for postoperative pain by VAS (0–10, 0 = no pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain), and diclofenac 1.5 mg/kg IV was given on demand or when VAS was found 4 or more. In case of persistent pain for >30 min after diclofenac administration, injection tramadol 50 mg IV was planned as second rescue analgesic. The requirement of rescue antiemetic during 0–2, 2–24, and 24–48 h was recorded. Complete response (no vomiting and no use of rescue medication) was evaluated at the 0–2, 2–6, 6–24, and 24–48 h time intervals after surgery. Any drug related adverse effects such as headache, dizziness, and abdominal disturbances (constipation/diarrhea) were recorded.

RESULTS

The statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS® 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows® software. The normally distributed data were compared using Student's t-test. For comparison of skewed data, Mann–Whitney U-test was applied. Qualitative or categorical variables were described as frequencies and compared with Chi-square or Fisher's exact test whichever was applicable. P values were corrected by the Bonferroni method and P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

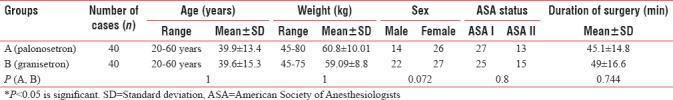

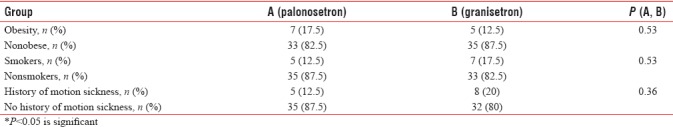

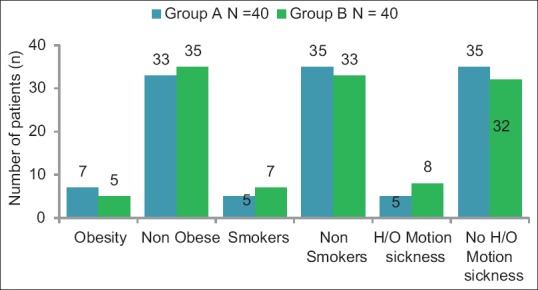

After screening, a total of 80 patients were enrolled in the study. The study was completed by all the patients. With respect to age, weight, PONV risk factors, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, the groups were comparable. The study was conducted after proper randomization. Demographic data (age, sex, and weight) and incidence of PONV risk factors of both the groups were comparable [Tables 1, 2 and Figures 2, 3]. Duration of surgery and CO2 insufflation time did not show a significant difference among groups [Table 1 and Figure 2]. This prospective was conducted on eighty patients undergoing elective laparoscopic surgeries which included cholecystectomy, appendectomy, hernioplasty, mesh repair, splenectomy, common bile duct exploration, totally extraperitoneal repair, and diagnostic laparoscopy (gynecological laparoscopic surgeries were not included in the study).

Table 1.

Comparative profile of demographic characteristics and surgery-related parameters

Table 2.

Groupwise distribution of risk factors in study groups

Figure 2.

Demographic profile of patients

Figure 3.

Groupwise comparison of risk factor distribution

On the basis of the ASA physical status classification, the distribution of patients in both groups is shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. In Group A, 13 out of 40 patients (32.5%) belonged to the ASA physical status Class II and 27 out of 40 patients (67.5%) to the ASA physical status Class I, while in Group B, 15 patients belonged to the ASA physical status Class II (37.5%) and 25 out of 40 to (62.5%) to the ASA physical status Class I. Pearson's Chi-square and Fisher's exact test was used to carry out the comparison. The difference was not significant. During both intraoperative and postoperative periods, the hemodynamic data were noted at regular intervals. There was no statistically significant difference in the measurement of vitals of the two groups.

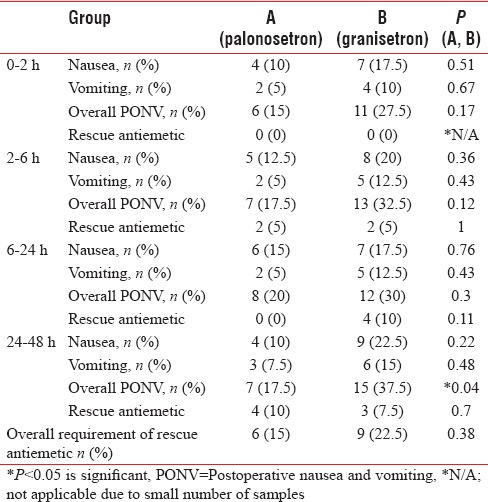

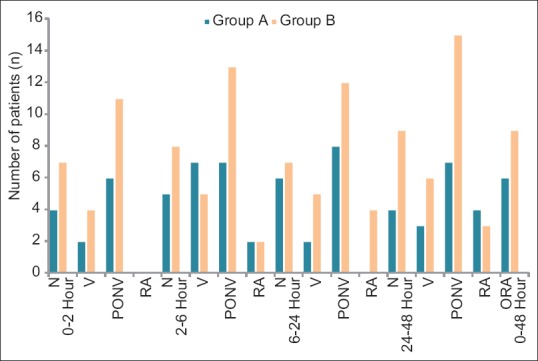

The distribution of both groups on the basis of occurrence of nausea, vomiting, overall PONV, and rescue antiemetic administration is displayed in Table 3 and Figure 4. The overall PONV at 0–2 h was high (27.5%) in Group B as compared to Group A (15%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.17). Furthermore, in both the groups, no rescue antiemetic was used.

Table 3.

Incidence of postoperative nausea, vomiting, and rescue antiemetic over 0-48 h

Figure 4.

Postoperative response of nausea, vomiting, and rescue antiemitic, N=nausea, V=vomiting, PONV= post operative nausea and vomiting. RA=rescue antiemetic, ORA=overall rescue antiemetic

At 2–6 h, the comparison of both groups is presented in Table 3 and Figure 4. In Group A, 7 out of 40 (17.5%) had overall PONV while the same in Group B was 13 out of 40 (32.5%). As is clear, the incidence of PONV was higher in Group B, but it was not statistically significant (P = 0.12). The requirement of antiemetic was same in both groups (n = 2).

At 6–24 h [Table 3 and Figure 4], 8 out of 40 (20%) in Group A and 12 out of 40 (30%) in Group B experienced overall PONV postoperatively. However, the difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.0.3). Similarly, in Group A, the requirement of rescue antiemetic at 6–24 h postoperatively was nil while the same in Group B was 10% (n = 4).

At 24–48 h, postoperatively, incidence of PONV is more in the patients of Group B, n = 15 (37.5%) as compared to Group A, n = 7 (17.5%) at 24–48 h [Table 3 and Figure 4]. The difference between the groups is statistically highly significant (P = 0.04). However, the number of patients requiring the rescue antiemetic was statistically not significant in both the groups.

Overall, significantly, a greater number of participants suffered PONV in the later (24–48 h) postoperative period if they were in the granisetron group compared with the palonosetron group. However, this difference between the groups was statistically insignificant in the early (0–24 h) postoperative period. The incidence of PONV in granisetron group was found to be maximum in the 24–48 h period, n = 15 (37.5). The incidence of PONV in palonosetron group was found to be maximum in 12–48 h period but in lesser number of patients, n = 8 (20%). In addition, the PONV score was less in the palonosetron group, implying that these patients had fewer episodes of PONV. Furthermore, the overall requirement of rescue antiemetic [Table 3 and Figure 4] was higher (n = 9) in granisetron group as compared to palonosetron group (n = 6). This requirement was higher in early postoperative period as compared to late postoperative period. However, the difference was small and comparable.

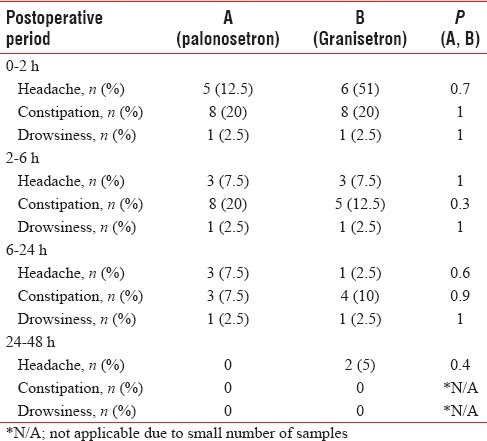

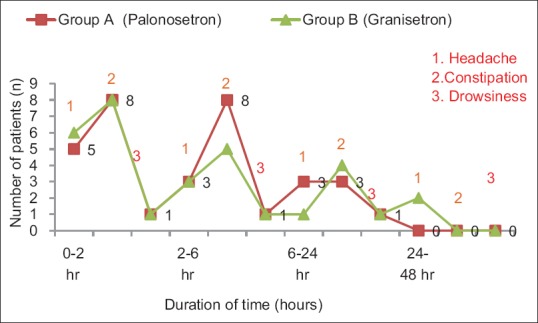

The incidence of most of the common side effects, such as headache, dizziness, drowsiness, and constipation [Table 4 and Figure 5], is similar in both the groups. As shown, the incidence of adverse effects is not clinically serious or significant. All the events are of mild-to-moderate severity and settle spontaneously without separate treatment.

Table 4.

Groupwise comparison of adverse effects in patients undergoing elective abdominal laparoscopic surgery

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of overall incidence of adverse effects in study groups

DISCUSSION

In modern anesthetic practice, PONV remains a significant problem. Depending on the various risk factors such as duration of surgery, the type of anesthetic agent used, and smoking habit, postoperative period is associated with variable incidence of nausea and vomiting.[17] PONV is associated with various adverse consequences such as delayed recovery, unexpected hospital admission, pulmonary aspiration, and wound dehiscence.[18] Therefore, in surgical patients, the prevention of PONV gets similar priority to that of alleviating postoperative pain.[19] The primary event in the initiation of vomiting reflex is the stimulation of 5-HT3 receptors. In periphery, these receptors are situated on the nerve terminal of vagus nerve and centrally on the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) of the area postrema.[20] The etiology of PONV is very complex in nature. The triggering factors are multiple inputs arriving from multiple areas. Anesthetic agents initiate the vomiting reflex by stimulating the central 5-HT3 receptors on CTZ.[18,21,22,23] Laparoscopic surgery, female gender, and nonsmoker status are considered as important independent risk factors for PONV.[24]

The reported incidence of PONV is 30%–80% within the first 24 h after laparoscopic surgery when no prophylactic antiemetic is administered.[7,25,26] The exact mechanism of PONV caused by pneumoperitoneum is not known. Pneumoperitoneum increases the risk of PONV by probably stimulating the mechanoreceptors in the gut. Furthermore, the intestinal ischemia induced by it may release serotonin and other neurotransmitters, which could lead to PONV.[27]

Acetylcholine and histamine are two important neurotransmitters of the vomiting center. Dopamine and 5-HT are two important neurotransmitters located in CTZ. 5-HT3 receptor is a subtype of serotonin receptor found in terminals of the vagus nerve and in certain areas of the brain. 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (granisetron and palonosetron) are highly specific and selective for acting against nausea and vomiting. They bind to the serotonin 5-HT3 receptor in CTZ and at vagal efferent in the gastrointestinal tract.[12,28] Based on the studies of Candiotti et al., the food drug agency has approved an effective dose of 0.075 mg for palonosetron. In our study, we also used palonosetron as 0.075 mg. With a single dose, palonosetron is effective in preventing nausea and vomiting for a longer period of time. This makes it more cost-effective. Granisetron produces irreversible block of the 5-HT3 receptors. This may account for the longer duration of this drug.[29,30] For the treatment of CINV, the effective dose of granisetron is 40–80 μg/kg). In this study, 2.5 mg was selected as dose of granisetron. This is within its effective dose range (40–80 μg/kg. The current study was planned in accordance with the studies conducted by Tramèr et al.[25] and del Giglio et al.[31] In this study, all surgical and anesthetic factors were well controlled. As a result, any difference in emesis-free episodes is directly attributed to the study drugs.

Our study suggests that palonosetron has an antiemetic effect which lasts longer than granisetron. The exact reason for the difference in effectiveness between palonosetron and granisetron is not known. In the present study, all the two antiemetics were shown to be almost equally effective in preventing nausea and vomiting during the first 24 h (0–24 h) after laparoscopic surgery. During first 24 h, there were no statistically significant differences in the number of PONV events between the two groups. The present study reports an overall PONV incidence of 20%–33% within the first 24-h postsurgery, without any statistical difference between the two groups. Our study demonstrates that the efficacy of palonosetron for the prevention of PONV is similar to that of granisetron during the early postoperative period (0–24 h). However, palonosetron appears to have a longer duration of action and its effect lasts for >24 h after the surgery. As a result, the palonosetron is more effective than granisetron for getting a complete response (no PONV and no rescue medication) for 24–48 h. The probable reason for the differences in effectiveness between granisetron and palonosetron could be related to the binding affinities of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and/or to the half-lives (palonosetron 40 h vs. granisetron 8–9 h).[10,12] In our study, a control group receiving placebo was not included. Aspinall and Goodman suggested that if active drugs are available, placebo-controlled trials may be unethical because PONV is very much disturbing and distressing event that can occur after laparoscopic surgery.

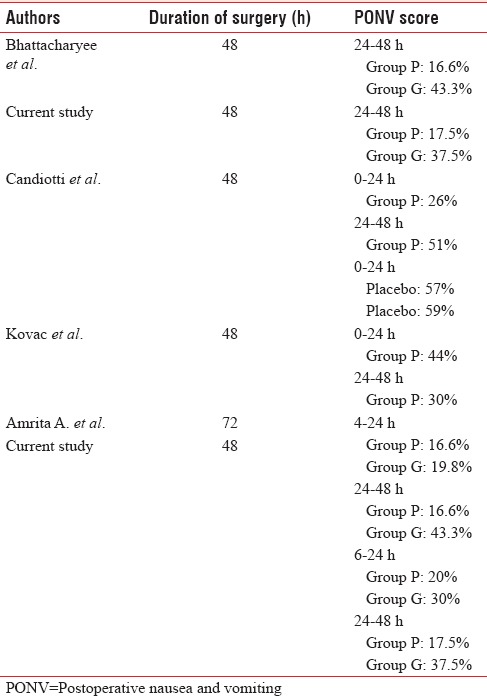

Our results are comparable with the study performed by Bhattacharjee et al.[32] [Table 5]. They did a comparative study between palonosetron and granisetron to prevent PONV after LC. They also concluded that prophylactic therapy with palonosetron is more effective than granisetron for the long-term prevention of PONV after laparoscopic surgery. Similar to our study, the incidence of PONV was maximum in the 24–48 h period with 43.3% of patients experiencing PONV in Group B and 16.6% in Group A while PONV incidence in our study was 37.5% in Group B and 17.5% in Group A in the 24–48 h period. This implied that the maximum incidence of PONV was observed in late postoperative period.

Table 5.

Comparative review of results of studies evaluating postoperative nausea and vomiting in abdominal laparoscopic surgery patients

Gugale and Bhalerao[33] conducted a study using granisetron 0.05 mg/kg and palonosetron 1.5 μg/kg in patients undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. In this study, all patients were observed postoperatively for 72 h divided into intervals, i.e. 0–4, 4–8, 8–12, 12–24, and 24–72 h. If we consider the 4–24 h period, the overall incidence of PONV in their study was 19.8% in Group B and 16.6% in Group A. This incidence is similar to our findings of 20% in Group A and 30% in Group B at 6–24 h postoperative period. Gugale and Bhalerao also concluded that the incidence of PONV was maximum in later postoperative period. At 24–48 h period, they noted 43.3% of patients experiencing PONV in Group B and 16.6% in Group A at 24–48 h period, and our values are 37.5% in Group B and 17.5% in Group A.

Similarly, according to Candiotti et al.,[34] incidence of PONV was 26% between 0 and 24 h and 51% in 24–48 h in patients who received 0.075 mg palonosetron before induction as compared to 57% and 59%, respectively, in patients who received placebo. This value is higher than that observed in our study. In the study conducted by Kovac et al.,[35] incidence of PONV was 44% in patients receiving palonosetron 0.075 mg in 0–24 h and 30% in 24–48 h. This value is again higher than that was observed by us. The variation in the observations may be due to surgical technique, intraoperative use of different anesthetic drugs, suctioning at the time of extubation, postural changes, and residual pneumoperitoneum.

Headache, drowsiness, dizziness, and constipation are the adverse events that are most frequently reported while using 5-HT3 receptor antagonists.[36] The adverse events observed in our study were similar among all two groups of patients.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrated that palonosetron and granisetron are almost equally effective as antiemetic against PONV during early postoperative period (0–24 h). During this period, the incidence of PONV is higher with granisetron, but the difference is statistically insignificant. However, prophylactic therapy for the long-term (24–48 h) prevention of PONV after laparoscopic surgery palonosetron is more effective than granisetron.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.NIH Consensus Conference. Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;269:1018–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elhakim M, Nafie M, Mahmoud K, Atef A. Dexamethasone 8 mg in combination with ondansetron 4 mg appears to be the optimal dose for the prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:922–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03016875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson EB, Bass CS, Abrameit W, Roberson R, Smith RW. Metoclopramide versus ondansetron in prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2001;181:138–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00574-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujii Y. The utility of antiemetics in the prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3173–83. doi: 10.2174/1381612054864911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JJ, Ho ST, Liu YH, Lee SC, Liu YC, Liao YC, et al. Dexamethasone reduces nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83:772–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.5.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feo CV, Sortini D, Ragazzi R, De Palma M, Liboni A. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of preoperative dexamethasone on nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:295–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nesek-Adam V, Grizelj-Stojcić E, Rasić Z, Cala Z, Mrsić V, Smiljanić A, et al. Comparison of dexamethasone, metoclopramide, and their combination in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:607–12. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leksowski K, Peryga P, Szyca R. Ondansetron, metoclopramid, dexamethason, and their combinations compared for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:878–82. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muchatuta NA, Paech MJ. Management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: Focus on palonosetron. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:21–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rojas C, Stathis M, Thomas AG, Massuda EB, Alt J, Zhang J, et al. Palonosetron exhibits unique molecular interactions with the 5-HT3 receptor. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:469–78. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fa74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoltz R, Cyong JC, Shah A, Parisi S. Pharmacokinetic and safety evaluation of palonosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 receptor antagonist, in U.S. and Japanese healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:520–31. doi: 10.1177/0091270004264641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, Sleeboom H, Mezger J, Peschel C, et al. Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: Results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1570–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moon YE, Joo J, Kim JE, Lee Y. Anti-emetic effect of ondansetron and palonosetron in thyroidectomy: A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:417–22. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blower P. A pharmacologic profile of oral granisetron (Kytril tablets) Semin Oncol. 1995;22:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez EA, Hesketh P, Sandbach J, Reeves J, Chawla S, Markman M, et al. Comparison of single-dose oral granisetron versus intravenous ondansetron in the prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized parallel study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:754–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez EA, Lembersky B, Kaywin P, Kalman L, Yocom K, Friedman C, et al. Comparable safety and antiemetic efficacy of a brief (30-second bolus) intravenous granisetron infusion and a standard (15-minute) intravenous ondansetron infusion in breast cancer patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Cancer J Sci Am. 1998;4:52–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lerman J. Surgical and patient factors involved in postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1992;69:24S–32S. doi: 10.1093/bja/69.supplement_1.24s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gan TJ. Risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1884–98. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000219597.16143.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macario A, Weinger M, Carney S, Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:652–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watcha MF, White PF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Its etiology, treatment, and prevention. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:162–84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SM, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative nausea and vomiting in children: Is there an association? Anesth Analg. 2000;90:571–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leslie K, Myles PS, Chan MT, Paech MJ, Peyton P, Forbes A, et al. Risk factors for severe postoperative nausea and vomiting in a randomized trial of nitrous oxide-based vs.nitrous oxide-free anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:498–505. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierre S, Corno G, Benais H, Apfel CC. A risk score-dependent antiemetic approach effectively reduces postoperative nausea and vomiting – A continuous quality improvement initiative. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:320–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03018235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, et al. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tramèr MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Efficacy, dose-response, and safety of ondansetron in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A quantitative systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1277–89. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryu J, So YM, Hwang J, Do SH. Ramosetron versus ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:812–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0670-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DK, Cheong IY, Lee GY, Cho JH. Low pressure (8mmHg) pneumoperitoneum does not reduce the incidence and severity of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) following gynecologic laparoscopy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2006;50:36–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bajwa SS, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Sharma V, Singh A, Singh A, et al. Palonosetron: A novel approach to control postoperative nausea and vomiting in day care surgery. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:19–24. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.76484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bicer C, Aksu R, Ulgey A, Madenoglu H, Dogan H, Yildiz K, et al. Different doses of palonosetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in children undergoing strabismus surgery. Drugs R D. 2011;11:29–36. doi: 10.2165/11586940-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujii Y, Tanaka H, Toyooka H. Granisetron reduces vomiting after strabismus surgery and tonsillectomy in children. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43:35–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03015955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Giglio A, Soares HP, Caparroz C, Castro PC. Granisetron is equivalent to ondansetron for prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: Results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 2000;89:2301–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11<2301::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattacharjee DP, Dawn S, Nayak S, Roy PR, Acharya A, Dey R, et al. A comparative study between palonosetron and granisetron to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26:480–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gugale AA, Bhalerao PM. Palonosetron and granisetron in postoperative nausea vomiting: A randomized double-blind prospective study. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:402–7. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.191121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Candiotti KA, Kovac AL, Melson TI, Clerici G, Joo Gan T Palonosetron 04-06 Study Group. A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:445–51. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817b5ebb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovac AL, Eberhart L, Kotarski J, Clerici G, Apfel C Palonosetron 04-07 Study Group. A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting over a 72-hour period. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:439–44. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817abcd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Habib AS, Gan TJ. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A review. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:326–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03018236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]