Abstract

Background:

Abdominal hysterectomy is associated with sever postoperative pain. Quadratus lumborum (QL) block is a regional analgesic technique which has an evolving role in postoperative analgesia.

Aims:

we aimed to compare ultrasound guided bilateral transverse abdominis plane (TAP) block versus bilateral QL block in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy.

Settings and Design:

This is a prospective randomized controlled double blinded study.

Patients and Methods:

Sixty adult female patients (ASA I-II), scheduled for total abdominal hysterectomy were randomized into two equal groups (TAP group and QL group). Each patient received general anesthesia plus bilateral TAP block or bilateral QL block. We recorded postoperative total dose of morphine used / 24 hours, Visual Analuge Scales (VAS) for pain (at 30 min, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 hours postoperative), duration of postoperative analgesia, total dose of fentanyl use intraoperative, number of patients needed rescue analgesia and any side effects.

Statistical Analysis:

Independent sample T test and Chi-Square (X2) test were used as appropriate.

Results:

Patients in QL group consumed significantly less fentanyl and morphine than patients in TAP group, VAS for pain was significant higher in TAP group than in QL group at all times, the duration of postoperative analgesia was shorter in TAP group than in QL group, the number of patients requested analgesia was significantly higher in TAP group than in QL group.

Conclusions:

Bilateral QL block provided better intraoperative and postoperative analgesia with less opioids consumption compared with bilateral TAP block, in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy.

Keywords: Hysterectomy, quadratus lumborum block, transversus abdominis plane block

INTRODUCTION

Multimodal pain management program is needed to control severe pain after abdominal hysterectomy which is considered as one of the major abdominal surgeries. Opioids (which are the analgesic of choice) have many adverse effects such as sedation, nausea, and vomiting. Hence, different methods are needed to control pain and decrease opioid consumption and its side effects.[1,2,3] Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block blocks the sensory afferent nerves run between the abdominal muscles and controls postoperative incisional pain.[4] Blanco[5] was the first who described the quadratus lumborum block (QLB). Somatic pain after upper and lower abdominal surgery can be controlled by QLB.[6] QLB can be performed for all generations (adult, pediatrics, and pregnant).[7,8] QLB is considered to be an easy technique to learn as it is easy to get the key sonoanatomic markers for QLB. The novice can learn this block after only a few performance of the procedure.[9] QLB produces effective postoperative analgesia after abdominal surgery, laparoscopic surgery, anterior abdominal wall surgery, and hip and femur surgery. The analgesic effect of QLB covers 24–48 h. While some authors inserted catheter for continuous infusion of the local anesthetic drug to extend the duration of postoperative analgesia, others added dexamethasone to local anesthetic to extend the effect of local anesthetic drugs.[9]

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to compare the effect of ultrasound-guided bilateral QLB versus bilateral ultrasound-guided TAP block on intraoperative and postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy under general anesthesia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This randomized prospective study was carried out in our hospital in the gynecologic department for 6 months (from July to December 2017) on 60 adult female patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Class I and II, aged between 45 and 60 years, and scheduled for total abdominal hysterectomy surgery after approval by local ethical committee. Written and informed consent was taken from each patient. Every patient received an explanation to the purpose of the study and had a secret code number to ensure privacy to participant and confidentiality of data.

Patients were randomly allocated into two equal groups (each 30 patients):

Group TAP (30 patients): Each patient received general anesthesia plus bilateral TAP block

Group QL (30 patients): Each patient received general anesthesia plus bilateral QLB.

Randomization

A computer system was used for randomization by creating a list of number each number referred to one of the two groups. Block randomization was used to ensure equality of the groups. Each number was sealed in an opaque envelope. Then, each patient was asked to choose one of the envelopes and give to an anesthesiologist who compared it to the computer-generated list and hence assigned her to one of the two groups.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included in the study if they were female, aged 45–60 years, with ASA Physical Status Class I and II, scheduled for abdominal hysterectomy under general anesthesia.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the study if they showed infection at injection site, allergy to local anesthetics, coagulation disorders, severe obesity, physical or mental diseases which could interfere with the evaluation of pain scores, or kidney failure or liver failure.

All patients were assessed preoperatively by history taking, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation. On arrival of the patients to the operative room, electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and capnography were applied. Baseline parameters such as systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean blood pressure, heart rate (HR), and arterial oxygen saturation were also recorded. Intravenous (IV) line was inserted and IV fluid was started. For both groups, general anesthesia was induced with IV injection of fentanyl (1 μg/kg) (Sunny Pharmaceutical, Egypt) and propofol (2 mg/kg) (AstraZeneca, UK), and then, atracurium (0.5 mg/kg) (GlaxoSmithKline, UK) was injected for endotracheal intubation. Mechanical ventilation was maintained to keep the end-expiratory CO2 values between 34 and 36 mmHg. Anesthesia was continued with isoflurane 1%–2% in 100% O2. Incremental dose of atracurium (0.1 mg/kg) was given every 30 min or when needed.

After endotracheal intubation and before the start of the surgery, anesthesiologist (who was blinded to the collected data until the end of the study) performed the block techniques and administered the medication. Both blocks were performed under complete aseptic precautions using ultrasound machine with high-frequency linear probe covered with sterile sheath (Sonoscape® SSI-6000, Chinawith12-6 MHz high-frequency linear probe) and 100-mm needle (B Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA).

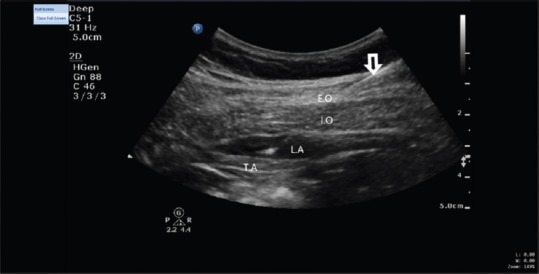

In TAP group, the probe was located between the iliac crest and the lower costal margin in the anterior axillary line at the level of umbilicus, and the layers of abdominal wall were identified (external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominis muscles). In-plane technique was used and the tip of the needle was inserted between the internal oblique and transverse abdominis muscles. After negative aspiration (to exclude intravascular injection), 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was injected. The same technique was performed on the other side [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Transversus abdominis plane block. EO = External oblique muscle, IO = Internal oblique muscle, TA = Transversus abdominis muscle, LA = Local anesthetic drugs (original figure)

In QL group, the patient was positioned supine with lateral tilt to perform the block, and the transducer was placed at the level of the anterior superior iliac spine and moved cranially until the three abdominal wall muscles were clearly identified. The external oblique muscle was followed posterolaterally until its posterior border was visualized (hook sign), leaving underneath the internal oblique muscle, like a roof over the QL muscle. The probe was tilted down to identify a bright hyperechoic line that represented the middle layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. The needle was inserted in plane from anterolateral to posteromedial. The needle tip was placed between the thoracolumbar fascia and the QL muscle, and after negative aspiration, the correct position of the needle was proved by injection of 5 mL of normal saline to confirm the space with a hypoechoic image and hydrodissection. An injection of 20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine was applied and the same technique was performed on the other side [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Quadratus lumborum block. QL = Quadratus lumborum muscle, EO = External oblique muscle, IO = Internal oblique muscle, TA = Transversus abdominis muscle, LA = Local anesthetic drugs, TLF = Thoracolumbar fascia (original figure)

Intraoperative fentanyl 1–2 ug/kg was given if the HR or the blood pressure or both increase >20% of the baseline. About 30 min before the end of the surgical procedure, paracetamol 1 g IV was given for all patients. Isoflurane was discontinued on completion of the surgical procedure, and neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg plus atropine 0.01 mg/kg was administered to reverse the effect of atracurium. After awakening from anesthesia and achieving an appropriate level of consciousness, the patient was discharged from the operating room. Visual analog scale (VAS) was used to assess the postoperative pain; if VAS >3 postoperatively, IV increment of morphine 3 mg was given. Any side effects were recorded as hypotension (systolic arterial pressure <90 mmHg), arrhythmia, bradycardia (HR <50 beat/min), nausea or vomiting, lower limb muscle weakness, or any other complications.

Primary outcome

The total dose of morphine used postoperatively/patient (rescue analgesia) for 24 h.

Secondary outcome

The total dose of fentanyl used intraoperatively was calculated

VAS for pain (ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 no pain and 10 maximum pain) was evaluated postoperatively at 30 min and 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h postoperative

Duration of postoperative analgesia (the time from recovery to the first given dose of morphine)

Number of patients needed rescue analgesia.

Sample size calculation

The total dose of morphine/patient was used to calculate sample size. The sample size was found to be 28 patients in each group assuming a standard deviation of 3.9 mg of morphine as rescue analgesic (from our pilot study), α error of 0.05, β error of 0.2, and a power of 80%. We intended to include 30 patients in each group to compensate for excluded patients.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, frequency, or frequency and percentage. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Independent sample t-test was used to analyze quantitative data. Qualitative data were analyzed using Chi-Square test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

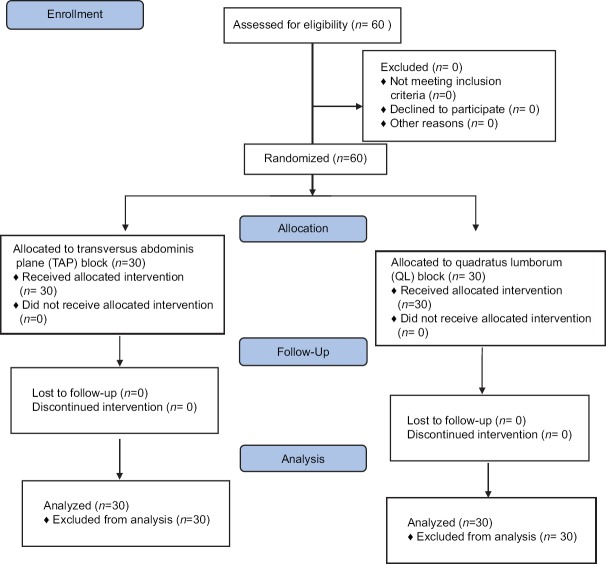

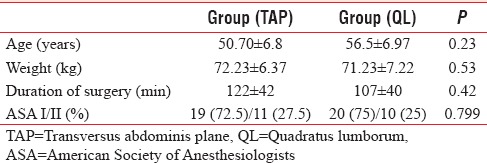

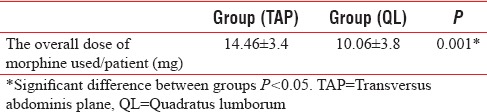

The study included 60 patients (30 patients in each group); no patients were excluded from the study [Figure 3]. No significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding age, weight, ASA Physical Status, or duration of surgery [Table 1]. Our results recorded that the mean amount of morphine used/patient postoperatively was significantly higher in TAP group than in QL group, P = 0.001 (14.46 ± 3.4 mg vs. 10.06 ± 3.8 mg, respectively) [Table 2]. VAS for pain was significantly higher in TAP group than in QL group at all the measured time postoperatively [Table 3]. Our results showed that the total amount of fentanyl used/patient intraoperatively was significantly higher in TAP group than in QL group, P = 0.001 (110.6 ± 22.4 μg vs. 43.16 ± 19.5 μg, respectively) [Table 4]. Duration of postoperative analgesia was shorter in TAP group than in QL group (8.33 ± 4 h vs. 15.1 ± 2.12 h, P = 0.001) [Table 4]. The number of patients requested analgesia was significantly higher in TAP group than in QL group (23 patients in TAP group vs. 8 patients in QL group, P = 0.017) [Table 4]. With regard to side effects, both groups were comparable and no serious complications were detected (one patient in each group suffered from vomiting and was treated with IV granesetrone 4 mg).

Figure 3.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1.

Demographic and operative data

Table 2.

Dose of morphine used/patient (mg) in the first 24 h postoperatively

Table 3.

Visual analog scale for pain

Table 4.

The dose of fentanyl used/patient and postoperative data

DISCUSSION

There are several types of abdominal truncal blocks with different effects, such as paravertebral block (which can last for 24 h when using long-acting local anesthetic),[10] TAP block and rectus sheath block (which have shorter time of analgesia),[11,12] and QLB.[7] To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized prospective study comparing the intraoperative and postoperative analgesic effect of QL and TAP blocks in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy.

Our results recorded that the overall fentanyl doses which were given intraoperatively, VAS for pain, morphine requirements after surgery, and number of patients needed analgesia after surgery were significantly less in QL group than in TAP group, which showed shorter duration of postoperative analgesia.

QLB is not technically difficult to be done because it is a superficial fascial block between posterior abdominal wall muscle (QL and erector spinae). QLB type 2 (posterior approach) is more safer than QLB type 1 (anterolateral) or the transmuscular approach (in between QL and psoas muscles). QLB does not aim to target a nerve but rather a fascial plane that is very bright, hyperechoic, and easily dissected. More superficial point of injection is more safer (bowel injury and intraperitoneal injection are less because the needle tip is separated from the peritoneum by the QL muscle) with better ultrasonographic resolution.[13]

The key for the analgesic effect for the QL block is the thoracolumbar fascia (TLF). TLF is a complex tubular structure formed from connective tissue. It is formed by binding of aponeuroses and fascial layers covering the back muscles. TLF connects the lumbar paravertebral region with the anterolateral abdominal wall. TLF continues cranially with endothoracic fascia, caudally with the fascia iliaca, its medial side attached to the thorasic and lumbar vertebrae, potentially ensuring the spread of anesthetics in the craniocaudal direction. It is suggested that the analgesic effect for the QL block is due to spread of the local anesthetics along the TLF and the endothoracic fascia into the paravertebral space.[13,14]

Our result was in line with the result recorded by Blanco et al.,[13] who reported that QLB was better than TAP block after cesarean section as it was associated with longer analgesic time (exceeding 24 h), less opioid consumption, and wider spread of analgesia. TAP block affected from T10 to T12 dermatomes while QLB covered from T7 to T12 dermatomes, and they explained their results by the spread of local anesthetics drugs either into the paravertebral space or in the thoracolumbar plane (which contains mechanoreceptors and high-density network of sympathetic fibers), this extensive spread with the QLB produced analgesia for somatic and visceral pain.[13]

The spread of local anesthetics during QLB to paravertebral space was reported by Carney et al.,[15] who recorded that the dermatome segments from T4 to L2 were covered by single shot QLB and they proved that by injecting contrast solution posteriorly which accumulated at the lateral border of QL, then spread in the posterior-cranial fashion to the anterior aspect of the QL and psoas major to paravertebral space.

Our result was in line with the study was done by Öksüz et al.,[16] who compared TAP block and QLB in pediatric patients undergoing lower abdominal surgery and reported that TAP block group showed significantly higher postoperative FLACC scores than QLB group (P < 0.05); furthermore, the number of patients who received rescue analgesia in the first 24 h postoperatively was significantly higher in TAP block group than in QLB group (P < 0.05). Parent's satisfaction scores were lower in TAP block group than in QLB group.

Furthermore, Murouchi et al.[17] investigated the relationship between the local anesthetics blood level and the efficacy of the QLB type 2 and TAP block in adults, and they found that in TAP block, the local anesthetic blood levels were higher than QLB type 2, but the analgesic effect was better with QLB type 2 than with TAP block, and this result was explained by the following, during QLB, some of the administered drug is thought to move from the intermuscular space into the paravertebral space which is filled with adipose tissue[7] and the local tissue perfusion of the adipose tissue is low which results in low absorption speed of a local anesthetic into the blood.[18]

Our result was in line with the results recorded by Baidya et al.,[19] who performed single injection QL transmuscular block between the QL and psoas major in lateral position on five children undergo pyeloplasty, and they reported that it was associated with good postoperative analgesia. Murouchi[20] used bilateral QL intramuscular block in pediatric patients undergoing laparoscopic appendectomy and reported that it was associated with successful postoperative analgesia. A meta-analysis published in 2016 compared eight trials studying the lateral technique of TAP block (the widely recognized TAP block in between internal oblique and transverses abdominis muscles) versus four trials studying the posterior technique for a TAP block (which is similar to QLB type 1) and reported that patients who had the posterior TAP block had less postoperative morphine consumption during 12–24-h and 24–48-h intervals.[21]

Limitations

I did not assess dermatomal levels of the block as I focused on opioid consumption and demands; however, I think that this did not affect the accuracy of our results and may be covered by further study.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study showed that in patients undergoing hysterectomy bilateral QLB provided more effective intraoperative and postoperative analgesia with less intraoperative fentanyl consumption, less VAS for postoperative pain, less number of patients needed analgesia after surgery, and less postoperative morphine consumption compared with bilateral TAP block, which showed shorter duration of postoperative analgesia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stanley G, Appadu B, Mead M, Rowbotham DJ. Dose requirements, efficacy and side effects of morphine and pethidine delivered by patient-controlled analgesia after gynaecological surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:484–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodhouse A, Mather LE. The effect of duration of dose delivery with patient-controlled analgesia on the incidence of nausea and vomiting after hysterectomy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:57–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng A, Swami A, Smith G, Davidson AC, Emembolu J. The analgesic effects of intraperitoneal and incisional bupivacaine with epinephrine after total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:158–62. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonnell JG, O'Donnell B, Curley G, Heffernan A, Power C, Laffey JG. The analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after abdominal surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:193–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000250223.49963.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco R. TAP block under ultrasound guidance: The description of a ‘non pops technique’. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:130. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadam VR. Ultrasound-guided quadratus lumborum block as a postoperative analgesic technique for laparotomy. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:550–2. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.119148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanco R, Ansari T, Girgis E. Quadratus lumborum block for postoperative pain after caesarean section: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32:812–8. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraborty A, Goswami J, Patro V. Ultrasound-guided continuous quadratus lumborum block for postoperative analgesia in a pediatric patient. A A Case Rep. 2015;4:34–6. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akerman M, Pejčić N, Veličković I. A review of the quadratus lumborum block and ERAS. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018;5:44. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal RR, Wallace AM, Madison SJ, Morgan AC, Mascha EJ, Ilfeld BM, et al. Single-injection thoracic paravertebral block and postoperative analgesia after mastectomy: A retrospective cohort study. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:371–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murouchi T, Iwasaki S, Yamakage M. Chronological changes in ropivacaine concentration and analgesic effects between transversus abdominis plane block and rectus sheath block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:568–71. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Støving K, Rothe C, Rosenstock CV, Aasvang EK, Lundstrøm LH, Lange KH, et al. Cutaneous sensory block area, muscle-relaxing effect, and block duration of the transversus abdominis plane block: A Randomized, blinded, and placebo-controlled study in healthy volunteers. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:355–62. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco R, Ansari T, Riad W, Shetty N. Quadratus lumborum block versus transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative pain after cesarean delivery: A Randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:757–62. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueshima H, Otake H, Jui-An L. Ultrasound-Guided Quadratus Lumborum Block: An Updated Review of Anatomy and Techniques. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7. doi: 10.1155/2017/2752876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carney J, Finnerty O, Rauf J, Bergin D, Laffey JG, Mc Donnell JG, et al. Studies on the spread of local anaesthetic solution in transversus abdominis plane blocks. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:1023–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Öksüz G, Bilal B, Gürkan Y, Urfalioğlu A, Arslan M, Gişi G, et al. Quadratus lumborum block versus transversus abdominis plane block in children undergoing low abdominal surgery: A Randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:674–9. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murouchi T, Iwasaki S, Yamakage M. Quadratus lumborum block: Analgesic effects and chronological ropivacaine concentrations after laparoscopic surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:146–50. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas JM, Schug SA. Recent advances in the pharmacokinetics of local anaesthetics. Long-acting amide enantiomers and continuous infusions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:67–83. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baidya DK, Maitra S, Arora MK, Agarwal A. Quadratus lumborum block: An effective method of perioperative analgesia in children undergoing pyeloplasty. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:694–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murouchi T. Quadratus lumborum block intramuscular approach for pediatric surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2016;54:135–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdallah FW, Laffey JG, Halpern SH, Brull R. Duration of analgesic effectiveness after the posterior and lateral transversus abdominis plane block techniques for transverse lower abdominal incisions: A meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:721–35. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]