Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful tool for visualizing traumatic brain injury(TBI)-related lesions. Trauma-induced encephalomalacia is frequently identified by its hyperintense appearance on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences. In addition to parenchymal lesions, TBI commonly results in cerebral microvascular injury, but its anatomical relationship to parenchymal encephalomalacia is not well characterized. The current study utilized a multi-modal MRI protocol to assess microstructural tissue integrity (by mean diffusivity [MD] and fractional aniosotropy [FA]) and altered vascular function (by cerebral blood flow [CBF] and cerebral vascular reactivity [CVR]) within regions of visible encephalomalacia and normal appearing tissue in 27 chronic TBI (minimum 6 months post-injury) subjects. Fifteen subjects had visible encephalomalacias whereas 12 did not have evident lesions on MRI. Imaging from 14 age-matched healthy volunteers were used as controls. CBF was assessed by arterial spin labeling (ASL) and CVR by measuring the change in blood-oxygen-level–dependent (BOLD) MRI during a hypercapnia challenge. There was a significant reduction in FA, CBF, and CVR with a complementary increase in MD within regions of FLAIR-visible encephalomalacia (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). In normal-appearing brain regions, only CVR was significantly reduced relative to controls (p < 0.05). These findings indicate that vascular dysfunction represents a TBI endophenotype that is distinct from structural injury detected using conventional MRI, may be present even in the absence of visible structural injury, and persists long after trauma. CVR may serve as a useful diagnostic and pharmacodynamic imaging biomarker of traumatic microvascular injury.

Keywords: : cerebral blood flow, cerebral vascular reactivity, diffusion tensor imaging, FLAIR, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

In the United States alone, over 2 million patients report to the emergency room for a brain injury annually, accounting for 50% of trauma-related deaths.1 Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a heterogeneous disease process, encompassing parenchymal contusions, intracranial hemorrhage, axonal injury,2 neuroinflammation,3,4 and microvascular injury.5 Each represents distinct endophenotypes present to varying degrees in individual patients. A better understanding of the spatial distribution of TBI endophenotypes in the brain, and their relationship to chronic disability will eventually aid in diagnosis, classification, and development of targeted treatments.6,7

Structural and microstructural brain tissue damage occurring after a TBI results from both the primary brain injury, caused by the mechanical forces to the head, and secondary injury, occurring hours to days after the initial impact attributed to hematoma expansion, brain edema, inflammation, and metabolic derangements. Recent evidence suggests that pathological changes in the brain likely accumulate long after the acute/subacute periods post-injury.8,9 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful tool for visualizing TBI-related anatomical damage. Trauma-induced encephalomalacia and gliosis are readily detected by fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI.10,11 Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a sensitive tool to detect cellular and microstructural alterations post-TBI.12–14 DTI abnormalities can be detected in various white matter structures years after a brain injury.15 A large body of literature suggests that DTI abnormalities, specifically reductions in fractional aniosotropy (FA), reflect axonal damage.16–19 However, DTI abnormalities are also informative of gray matter damage.12,20 Efforts are currently underway to detect subject-specific DTI abnormalities that can be clinically utilized to better diagnose and follow TBI-related structural abnormalities.21,22 Although structural changes to brain tissue are the most salient feature of TBI, it does not fully characterize TBI pathophysiology nor fully account for patient outcomes.

Traumatic cerebral vascular injury is a common endophenotype of TBI whose role in in TBI pathophysiology and outcome is often overlooked.5 Pathological studies in both experimental animals and humans have demonstrated extensive cerebral microvascular injury in both acute and chronic TBI, including after relatively minor injuries. Pathologically, evidence of vascular injury can be found distal to sites of contusions.23 Clinically, cerebrovascular abnormalities in the acute phase of severe TBI have been associated with worse outcome.24–26 Alterations in cerebral blood flow (CBF) post-TBI are common, and optimization of CBF has been used as a therapeutic target, particularly in severe TBI.26–29 In addition to these acute disruptions, alterations in blood flow and blood vessel function persist long after injury.30 Cerebral vascular reactivity (CVR), a measure of blood vessel dilation in response to a vasoactive stimulus, is impaired post-TBI.31–33 Unlike CBF, which is influenced by tissue metabolic demand in addition to vascular integrity, CVR may be a more specific measure of cerebral microvasculature dysfunction post-TBI.

The current study utilized multiple MRI modalities to study vascular and structural injury in regions of visible encephalomalacia as well as normal-appearing tissue in a cohort of chronic TBI subjects. We hypothesized that physiological vascular injury, measured by CVR, would be more pervasive than chronic parenchymal damage and perhaps prove to be a useful imaging biomarker of chronic TBI as well as a biomarker of the vascular TBI endophenotype.

Methods

Population study

We recruited 41subjects (27 with TBI and 14 control subjects) between the ages of 18 and 55. Subjects were consented under an institutional review board–approved protocol and prospectively studied in this ClinicalTrials.gov registered study, “Sildenafil for Cerebrovascular Dysfunction in Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury” (NCT01762475). Patients with TBI were eligible if they had suffered a moderate or severe TBI (by Department of Defense criteria34 defined by at least one of the following criteria: initial Glasgow Coma Score between 3 and 12, post-traumatic amnesia >24 h, or TBI-related abnormality on neuroimaging, i.e., computed tomography [CT] or MRI). TBI participants had been injured 6 months or more before enrollment. Patients were excluded if they had: penetrating TBI, pre-existing disabling neurological or psychiatric disorder, current pregnancy, or an unstable pulmonary or vascular disorder. Controls were sex- and age-matched (Table 1). Healthy controls (HCs) were enrolled if they had no history of TBI, pre-existing disabling neurological or psychiatric disorders, or current pregnancy.

Table 1.

Age and Sex Matching for Healthy Controls (HC) and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Subjects

| Age (mean ± SD) | Sex (%male) | |

|---|---|---|

| HC (n = 14) | 38.9 ± 6.8y | 78 |

| TBI (n = 27) | 37.6 ± 11.1y | 71 |

| t(39) = 0.28; p = 0.78 | χ2(1) = 0.32; p = 0.57 |

SD, standard deviation; y, years.

Imaging sequences

MRI was performed on a Siemens Biograph mMR, a fully integrated 3 Tesla MRI/positron emission tomography scanner. T1 magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE), susceptibility-weighted imaging, T2-gradient echo sequences, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), DTI, FLAIR, pulsed arterial spin labeling (ASL) and MRI/blood-oxygenation-level–dependent (MRI-BOLD) sequences were acquired on each subject.

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

FLAIR images were acquired with the following parameters: repetition time [TR] = 9090 ms, echo time [TE] = 112 ms, inversion time [TI] = 2450 ms, flip angle = 120 degrees, and voxel size = 0.9 × 0.9 × 3.0 mm3.

Diffusion tensor imaging

DWIs were acquired on the same scanner with parameters TR = 8900s, TE = 92 ms, flip angle = 90 degrees, voxel size = 2 × 2 × 3.5 mm3, matrix size = 128 × 128, and slices = 40. One image at b = 0 s/mm2 and 12 images with noncollinear directional gradients at b = 1000 s/mm2 were acquired twice with reversed-phase encoding gradients (also known as blip-up blip-down).35

Arterial spin labeling

ASL images were acquired using a pulsed sequence with the PICORE Q2TIPS labeling scheme, on the same scanner. The following parameters were established for the acquisition of 111 two-dimensional/echo planar imaging (EPI) volumes: TR/TE = 2700/15 ms, TI1/TI2 = 700/1800 ms.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging with hypercapnia challenge (cerebral vascular reactivity)

The parameters used were: TR/TE = 2000/25 msec, flip angle = 80 degrees, field of view = 220 × 220 mm2, matrix = 64 × 64, 36 slices, thicknes s = 3.6 mm, no gap between slices, 210 volumes. During the sequence, each participant underwent hypercapnia challenge according to the methods developed previously.36,37 Hypercapnia is induced by breathing alternatively room air and 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) mixed with 21% O2 and 74% N2. End-tidal CO2 (EtCO2) was measured continuously during the experiment using a capnograph (Model 9004; Smiths Medical, Norwell, MA). Arterial oxygenation and pulse were recorded by a fingertip pulse oximeter throughout the experiment.

Data processing

Diffusion tensor imaging

Images were processed using the CATNAP software38 for tensor estimation, with the exception that EPI and eddy current distortions were removed using the TOPUP software39 within the FMRIB software library (FSL),40 which takes advantage of the blip-up blip-down acquisition. This pipeline also takes into account motion correction and adjustments to the gradient table performed based on patient position. Linear tensor estimation was performed followed by computation of FA.

Cerebral blood flow

Image data analyses were performed with the Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM12) and ASL data processing toolbox. The control and label ASL images were realigned and resliced to correct for head motion. Images were smoothed using an isotropic Gaussian kernel with a 4-mm full-width at half-maximum. CBF images were reconstructed using the ASL Data Processing Toolbox: ASLtbx.

Cerebral vascular reactivity

Voxel-by-voxel CVR maps were calculated based on a linear regression between BOLD signal time courses and the vascular input function. The BOLD response signal is delayed from the EtCO2, which corresponds to the time needed for the blood to travel between the lungs to the cerebrovascular network. The EtCO2 time delay is individually corrected to achieve the maximum correlation between the two measures. CVR data were processed using a general linear model, with the EtCO2 time course utilized as the regressor to generate CVR maps for each subject. The full method is previously described by Lu and colleagues.41

All subject images (FA, mean diffusivity [MD], CBF, and CVR) were rigidly coregistered with their associated MPRAGE image using SPM12. The neuroradiologist's reports were used to identify which subjects had visible encephalomalacias (n = 15) and which did not (n = 12). The visible encephalomalacias were manually drawn on MPRAGE-registered FLAIR images by a researcher familiar with brain MRI (Fig. 1). Visible MD and FA abnormalities were taken into consideration when delineating the region of encephalomalacia. The manually drawn regions were converted to binary masks using MIPAV. All MRI maps and binary masks were then normalized into a common space (MNI-atlas) using SPM12. Normalization was performed using the MPRAGE images, and then applying the same transformation to all other images. The MD, FA, CBF, and CVR maps were then z-transformed using the pool of healthy controls from the study. The average z-score within the encephalomalacia and in the normal-appearing tissue (defined as all brain tissue outside the encephalomalacia) for each subject was extracted using a custom Matlab script (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). For some images, the mask for the enephalomalacia extended slightly outside the brain attributed to geometric distortions in those images. The voxels in those extended areas were not removed for the purposes of this study, because they encompassed a very small area and therefore minimally contributed to the extracted value for that region.

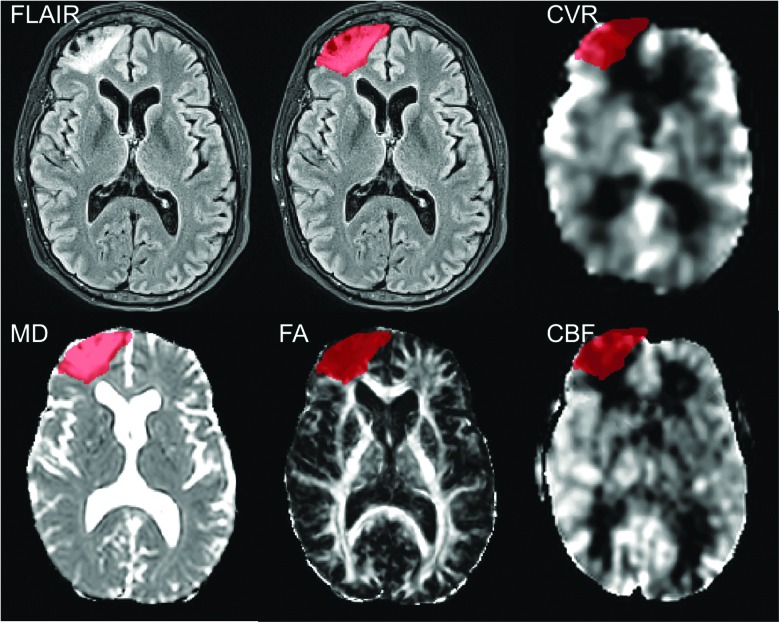

FIG. 1.

Representative images of encephalomalacia in FLAIR, CVR, MD, FA, and CBF maps. The region of encephalomalacia (red) shows imaging abnormalities in multiple MRI modalities. CBF, cerebral blood flow; CVR, cerebral vascular reactivity; FA, fractional anisotropy; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MD, mean diffusivity.

Statistical analysis

MRI maps were z-transformed using FSL42,43 to create voxel-wise mean and standard deviations (SDs) measured in 14 uninjured healthy volunteers. Group statistics were performed in Graphpad Prism (version 7; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Regions of encephalomalacia were statistically compared to normal appearing tissue using a one-tailed unpaired t-test. HCs, TBI/MRI+, and TBI/MRI− were compared using an ordinary one-way analysis of variance with Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons post-hoc test.

Results

Study population

TBI subjects (n = 27) were enrolled a median of 1.9 years post-injury (interquartile range [IQR] = 1.8 years; Table 2). Five TBI subjects received neurosurgical intervention (craniotomy or craniectomy) for their injury. The majority of brain injuries occurred as a result of road traffic incidents (58%). All but 3 subjects had acute TBI-related neuroimaging findings on initial cranial CT (e.g., subdural, subarachnoid, and/or intraparenchymal hemorrhages, among other acute lesions). A clinical neuroradiologist reviewed all MRI images from the 27 chronic TBI subjects. Many subjects with trauma-related abnormalities on CT scans in the acute period showed resolution at the time of study enrollment and MRI acquisition. Of the 27 TBI subjects, 15 were identified as having visible regions of encephalomalacia and 12 were classified as having grossly normal appearing brain tissue (Table 2).

Table 2.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Subjects with Visible Encephalomalacia on Conventional MRI (TBI/MRI+) Compared to TBI Subjects without Visible Encephalomalacia on Conventional MRI (TBI/MRI−)

| N | Age (mean ± SD) | Sex (%male) | Time post-injury (median, IQR) | GOS-E (median, IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI | 27 | 37.6 ± 11.1y | 71 | 1.9, 1.8 y | 7, 1.5 |

| TBI/MRI+ | 15 | 39.7 ± 10.7y | 67 | 1.9, 1.5 y | 6, 1.5 |

| TBI/MRI− | 12 | 35.0 ± 11.5y | 75 | 1.8, 1.9 y | 7, 2 |

| t(25) = 1.6; p = 0.13 | χ2(1) = 0.22; p = 0.64 | U = 87; p = 0.90 | U = 62; p = 0.18 |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; GOS-E, Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended, y, years.

Vascular and structural abnormalities within the region of encephalomalacia

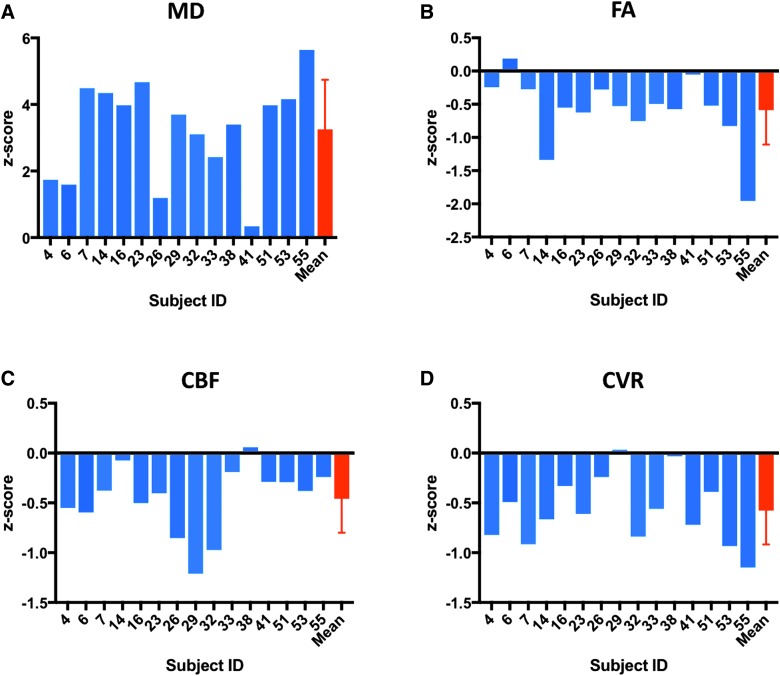

Vascular or structural imaging abnormalities were assessed in regions of encephalomalacia in chronic TBI patients (Fig. 1). Mean lesion volume was 57.4 (±44.7) cm3, which is 2.9% (±2.2%) of the total brain volume. The mean z-score value within the region of encephalomalacia is reported for each subject as well as across all 15 subjects (Fig. 2). Within the same region, z-score magnitudes were not consistently altered across the four different metrics. Overall, FA, CVR, and CBF showed negative mean z-scores within regions of encephalomalacia (mean ± SD: FA: −0.59 ± 0.52; CVR: −0.58 ± 0.34; CBF: −0.46 ± 0.34), whereas MD showed a positive mean z-score within regions of encephalomalacia (3.2 ± 1.5). These results indicate that, as expected, both microstructural and vascular imaging metrics are altered in chronic encephalomalacia.

FIG. 2.

All MRI modalities are altered within the region of encephalomalacia. TBI subjects with visible encephalomalacias were assessed. (A) MD was altered in the region of encephalomalacia for all subjects with an overall positive mean z-score within the abnormal region across subjects. (B–D) FA, CVR, and CBF showed negative z-score values within the region of encephalomalacia for several subjects, with an overall negative mean z-score across all 15 subjects. CBF, cerebral blood flow; CVR, cerebral vascular reactivity; FA, fractional anisotropy; MD, mean diffusivity; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Vascular abnormalities in normal-appearing brain tissue in chronic traumatic brain injury

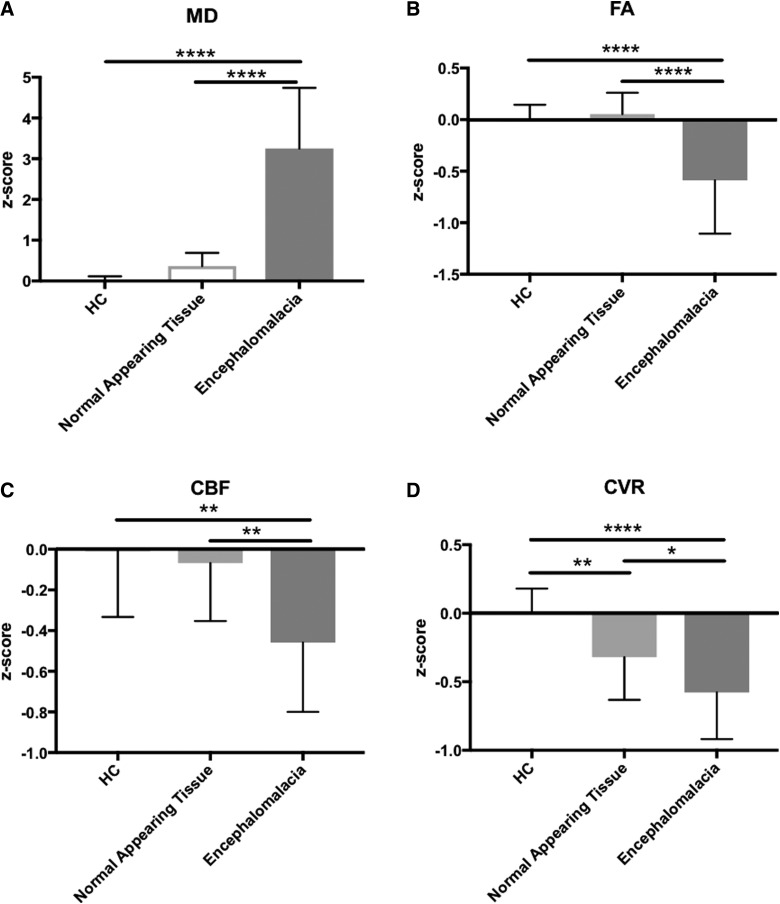

The regions of encephalomalacia were then compared to normal-appearing tissue within the chronic TBI subjects and HCs (Fig. 3). Mean z-score values were extracted for the normal-appearing tissue and in regions of visible encephalomalacia in the TBI subjects. For HCs, whole-brain MRI metric values were converted to z-scores. Regions of encephalomalacia showed a significant increase in MD (f2, 41 = 58.75, p < 0.0001; post-hoc, p < 0.0001) and a significant decrease in FA (f2, 41 = 16.83, p < 0.0001; post-hoc, p < 0.0001), CBF (f2, 41 = 8.802, p = 0.0007; post-hoc, p = 0.0012), and CVR (f2, 41 = 14.62, p < 0.0001; post-hoc, p < 0.0001) as compared to HCs. In the normal-appearing tissue, only CVR was significantly reduced compared to healthy control tissue (post-hoc, p = 0.0093). MD, FA, and CBF were not significantly altered in the normal-appearing tissue when compared to HC tissue (MD: post-hoc, p = 0.2809; FA: post-hoc, p = 0.6657; CBF: post-hoc, p = 0.5709). These results indicate CVR is altered in structurally normal-appearing tissue.

FIG. 3.

The region of encephalomalacia is significantly different than normal appearing tissue for all MRI modalities. Within the region of encephalomalacia, there is a significant increase in MD (A) and a significant decrease in FA (B), CBF (C), and CVR (D) as compared to normal-appearing tissue (p < 0.05). (D) When compared to healthy controls, only CVR shows a significant alteration in normal-appearing tissue. ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. CBF, cerebral blood flow; CVR, cerebral vascular reactivity; FA, fractional anisotropy; MD, mean diffusivity; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

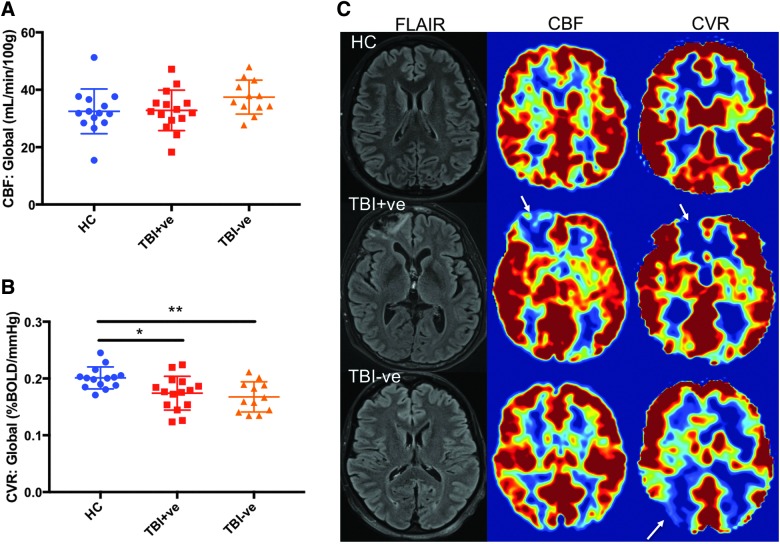

To determine whether tissue without visible encephalomalacia have regions of vascular dysfunction, TBI subjects with visible encephalomalacia (TBI/MRI+, n = 15) were compared to TBI subjects without visible encephalomalacia (TBI/MRI−, n = 12) on conventional MRI (Fig. 4). Whole-brain mean CBF was not significantly different between HC, TBI/MRI+, and TBI/MRI− groups (f2,38 = 2.0; p = 0.15). Whole-brain mean CVR was significantly decreased in the TBI/MRI+ and TBI/MRI− groups relative to controls (f2,38 = 6.4, p = 0.0040; post-hoc, TBI/MRI+: p = 0.015, TBI/MRI−: p = 0.0062). Overall, the mean whole-brain CVR was not significantly different between the TBI/MRI+ and the TBI/MRI− group (post-hoc, p = 0.5167). Given that CVR in regions of encephalomalacia was significantly reduced, an additional analysis was done to compare only the normal appearing tissue CVR in the TBI/MRI+ subjects to the mean whole-brain CVR for the TBI/MRI− subjects. There was no significant difference between the normal-appearing tissue CVR in TBI/MRI+ subjects and the mean whole-brain CVR for TBI/MRI- subjects (t(25) = 0.4916, p = 0.6273; data not shown). Representative images from a single subject from each group (TBI/MRI+, TBI/MRI−, and HC) show a reduction in CBF and CVR within the region of encephalomalacia (Fig. 4C). In the subject with no visible encephalomalacia, CBF appears normal throughout the brain while a large reduction in CVR can be observed in a region of normal appearing tissue (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that CVR abnormalities occur in seemingly intact brain regions in individuals with chronic TBI.

FIG. 4.

CVR is significantly altered in TBI subjects without structural MRI abnormalities. (A) Comparison of TBI subjects with visible encephalomalacias on conventional MRI (TBI/MRI+) to TBI subjects without visible encephalomalacias (TBI/MRI−) showed no significant difference in whole-brain CBF (p > 0.05). (B) Both TBI/MRI+ and TBI/MRI− showed a significant decrease in CVR relative to controls (p < 0.05). (C) Representative images indicate decreased CBF and CVR in the region of encephalomalacia (arrows). No apparent decrease in CBF is observed in the subject without encephalomalacia, whereas a large decrease in CVR can be observed in structurally normal-appearing tissue (arrow). **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05. CBF, cerebral blood flow; CVR, cerebral vascular reactivity.

Discussion

The current study shows that both microstructural (MD, FA) and vascular (CBF, CVR) imaging modalities are altered in regions of visible encephalomalacia post-TBI. In normal-appearing tissue without visible structural damage, CVR is also altered, indicating that there is vascular dysfunction post-TBI that extends beyond the visible lesions. These findings are significant because they indicate that vascular injury: 1) is spatially distinct from microstructural damage in chronic TBI; 2) is present even in the absence of large structural injury; and 3) persists years post-injury.

As expected, DTI imaging metrics showed abnormalities within regions of encephalomalcia. MD was elevated to some degree for all subjects with visible encephalomalacia whereas FA was decreased. Not surprisingly, both CBF and CVR were substantially decreased in the regions of structural encephalomalacia. Interestingly, the magnitude of change was not consistent between metrics within the same subject: that is, an unusually large decrease in CVR within a region was not predictive of an equally large increase in MD or decrease in FA or CBF. This supports the current study's finding that vascular and structural damage represent distinct endophenotypes in chronic TBI, even within regions of encephalomalacia.

Traumatic microvascular injury is a near-universal feature of severe TBI, given that more than 90% of autopsied brains from post-mortem TBI cases exhibit ischemic brain damage, but it is also observed extensively in experimental mild TBI.44–46 Swelling of endothelial cells on cerebral arterioles are apparent post-injury on vessels that have not been transected.47 Distribution and location of vascular injury in chronic TBI is distinct from structural damage detected by MRI, indicating that the pathophysiology of chronic TBI is more diffuse/extensive than can be appreciated using conventional MRI techniques. CVR abnormalities were found in structurally normal-appearing tissue and in chronic TBI subjects without lesions visible by conventional MRI techniques. The relationship between vascular and structural damage has been investigated in several animal and clinical studies48–50; however, few studies use CVR as an indicator of vascular functional integrity. CVR as measured by functional MRI has only recently been utilized in brain injury studies.31–33 CVR in response to a vasodilatory stimulus such as hypercapnia can accurately be measured by either ASL or MRI-BOLD.51 Control of the vasoactive stimulus as well as the sequence utilized can affect the sensitivity of CVR.51–53 The lack of CBF abnormalities within regions of decreased CVR in the chronic TBI group suggests that these findings are not attributed to decreased metabolic demand or blood vessel loss in that area. Our data suggest that CVR is sensitive to dysfunction of the cerebral vasculature that occurs after chronic TBI. CVR could serve as a useful predictive biomarker to help stratify patients for therapeutic trials by identifying traumatic microvascular injury in chronic TBI subjects with and without structural imaging abnormalities.

The current study is limited by the resolution of MRI modalities. The voxel size utilized was on the order of cubic millimeters, a common voxel size for both clinical and research uses. Subtle structural or vascular abnormalities, such as damage to neurons immediately found at the interface of a vessel with the surrounding parenchyma or a small number of capillaries, were not detected because of averaging effects within a voxel. The current study focused on large and robust imaging abnormalities, traversing large volumes of tissue. Large regions of decreased CVR were often not associated with a visible structural abnormality.

The highly plastic nature of the cerebral vasculature makes it a compelling therapeutic target for TBI.5 Neurovascular therapeutic candidates, such at phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors54–56 and 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors,57,58 have shown efficacy in pre-clinical studies. In a rodent model of stroke, sildenafil promoted neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and axonal remodeling in the peri-infarct zone, as well as attenuated functional deficits.54–56 The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, has been shown to increase circulating endothelial progenitor cells and angiogenesis in a TBI rodent model.57 Specific therapeutic targeting of traumatic vascular injury in TBI patients may improve clinical outcome. Sildenafil has been shown to increase CVR specifically within regions with decreased CVR in chronic TBI subjects.33,59 This suggests CVR may be a useful biomarker to monitor response to therapy as well. These findings highlight the need for further study of traumatic vascular injury as distinct endophenotype of TBI.

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors' laboratory was supported by the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine (CNRM), Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS; Bethesda, MD) by the Military Clinical Neuroscience Center of Excellence (MCNCoE), Department of Neurology, USUHS, and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health. Support from the TBI Endpoints Development (TED) Project (DoD W81XWH-14-2-0176) is also acknowledged.

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Department of Defense, Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine (CNRM), Military Clinical Neuroscience Center of Excellence (MCNCoE), or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. (2010). Rates of TBI-related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths: United States, 2001–2010 | Data | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://data.cdc.gov/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-/Rates-of-TBI-related-Emergency-Department-Visits-H/45um-c62r.

- 2.Johnson V.E., Stewart W., and Smith D.H. (2013). Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 246, 35–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziebell J.M., and Morganti-Kossmann M.C. (2010). Involvement of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Neurother. J. Am. Soc. Exp. Neurother. 7, 22–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziebell J.M., Adelson P.D., and Lifshitz J. (2015). Microglia: dismantling and rebuilding circuits after acute neurological injury. Metab. Brain Dis. 30, 393–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenney K., Amyot F., Haber M., Pronger A., Bogoslovsky T., Moore C., and Diaz-Arrastia R. (2016). Cerebral vascular injury in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 275, Pt. 3, 353–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saatman K.E., Duhaime A.-C., Bullock R., Maas A.I.R., Valadka A., and Manley G.T. (2008). Classification of traumatic brain injury for targeted therapies. J. Neurotrauma 25, 719–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz-Arrastia R., Kochanek P.M., Bergold P., Kenney K., Marx C.E., Grimes C.J.B., Loh L.Y., Adam L.G.E., Oskvig D., Curley K.C., and Salzer C.W. (2014). Pharmacotherapy of Traumatic Brain Injury: State of the Science and the Road Forward: Report of the Department of Defense Neurotrauma Pharmacology Workgroup. J. Neurotrauma 31, 135–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson V.E., Stewart J.E., Begbie F.D., Trojanowski J.Q., Smith D.H., and Stewart W. (2013). Inflammation and white matter degeneration persist for years after a single traumatic brain injury. Brain 136, 28–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay J.R., Johnson V.E., Young A.M.H., Smith D.H., and Stewart W. (2015). Blood-brain barrier disruption is an early event that may persist for many years after traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 74, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashikaga R., Araki Y., and Ishida O. (1997). MRI of head injury using FLAIR. Neuroradiology 39, 239–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee B., and Newberg A. (2005). Neuroimaging in traumatic brain imaging. NeuroRx 2, 372–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchinson E.B., Schwerin S.C., Avram A.V., Juliano S.L., and Pierpaoli C. (2018). Diffusion MRI and the detection of alterations following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 96, 612–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J.Y., Bakhadirov K., Devous M., Abdi H., McColl R., Moore C., Marquez de la Plata C., Ding K., Whittemore A., Babcock E., Rickbeil T., Dobervich J., Kroll D., Dao B., Mohindra N., Madden C., and Diaz-Arrastia R. (2008). Diffusion tensor tractography of traumatic axonal injury. Arch. Neurol. 65, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J.Y., Bakhadirov K., Abdi H., Devous Sr., M.D., Marquez de la Plata C.D., Moore C., Madden C.J., and Diaz-Arrastia R. (2011). Longitudinal changes of structural connectivity in traumatic axonal injury. Neurology 77, 818–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mac Donald C.L., Barber J., Andre J., Evans N., Panks C., Sun S., Zalewski K., Elizabeth Sanders R., and Temkin N. (2017). 5-Year imaging sequelae of concussive blast injury and relation to early clinical outcome. Neuroimage Clin. 14, 371–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mac Donald C.L., Dikranian K., Bayly P., Holtzman D., and Brody D. (2007). Diffusion tensor imaging reliably detects experimental traumatic axonal injury and indicates approximate time of injury. J. Neurosci. 27, 11869–11876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Q., Qu C., Chopp M., Ding G.L., Nejad-Davarani S.P., Helpern J.A., Jensen J.H., Zhang Z.G., Li L., Lu M., Kaplan D., Hu J., Shen Y., Kou Z., Li Q., Wang S., and Mahmood A. (2011). MRI evaluation of axonal reorganization after bone marrow stromal cell treatment of traumatic brain injury. NMR Biomed. 24, 1119–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van de Looij Y., Mauconduit F., Beaumont M., Valable S., Farion R., Francony G., Payen J.F., and Lahrech H. (2012). Diffusion tensor imaging of diffuse axonal injury in a rat brain trauma model. NMR Biomed. 25, 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett R.E., Mac Donald C.L., and Brody D.L. (2012). Diffusion tensor imaging detects axonal injury in a mouse model of repetitive closed-skull traumatic brain injury. Neurosci. Lett. 513, 160–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Budde M.D., Janes L., Gold E., Turtzo L.C., and Frank J.A. (2011). The contribution of gliosis to diffusion tensor anisotropy and tractography following traumatic brain injury: validation in the rat using Fourier analysis of stained tissue sections. Brain 134, 2248–2260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J.B., Hart T., Whyte J., Rabinowitz A., Detre J.A., and Kim J. (2017). Inter-subject variability of axonal injury in diffuse traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 34, 2243–2253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaker M., Erdogmus D., Dy J., and Bouix S. (2017). Subject-specific abnormal region detection in traumatic brain injury using sparse model selection on high dimensional diffusion data. Med. Image Anal. 37, 56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hay J.R., Johnson V.E., Young A.M., Smith D.H., and Stewart W. (2015). Blood-brain barrier disruption is an early event that may persist for many years after traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 74, 1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preiksaitis A., Krakauskaite S., Petkus V., Rocka S., Chomskis R., Dagi T.F., and Ragauskas A. (2016). Association of severe traumatic brain injury patient outcomes with duration of cerebrovascular autoregulation impairment events. Neurosurgery 79, 75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ojha B.K., Jha D.K., Kale S.S., and Mehta V.S. (2005). Trans-cranial Doppler in severe head injury: Evaluation of pattern of changes in cerebral blood flow velocity and its impact on outcome. Surg. Neurol. 64, 174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaloostian P., Robertson C., Gopinath S.P., Stippler M., King C.C., Qualls C., Yonas H., and Nemoto E.M. (2012). Outcome prediction within twelve hours after severe traumatic brain injury by quantitative cerebral blood flow. J. Neurotrauma 29, 727–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouma G.J., and Muizelaar J.P. (1995). Cerebral blood flow in severe clinical head injury. New Horiz. 3, 384–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly D.F., Martin N.A., Kordestani R., Counelis G., Hovda D.A., Bergsneider M., McBride D.Q., Shalmon E., Herman D., and Becker D.P. (1997). Cerebral blood flow as a predictor of outcome following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 86, 633–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akbik O.S., Carlson A.P., Krasberg M., and Yonas H. (2016). The utility of cerebral blood flow assessment in TBI. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 16, 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jullienne A., Obenaus A., Ichkova A., Savona-Baron C., Pearce W.J., and Badaut J. (2016). Chronic cerebrovascular dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 609–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis M.J., Ryner L.N., Sobczyk O., Fierstra J., Mikulis D.J., Fisher J.A., Duffin J., and Mutch W.A.C. (2016). Neuroimaging assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity in concussion: current concepts, methodological considerations, and review of the literature. Front. Neurol. 7, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mutch W.A.C., Ellis M.J., Ryner L.N., Morissette M.P., Pries P.J., Dufault B., Essig M., Mikulis D.J., Duffin J., and Fisher J.A. (2016). Longitudinal brain magnetic resonance imaging CO2 stress testing in individual adolescent sports-related concussion patients: a pilot study. Front. Neurol. 7, 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amyot F., Kenney K., Moore C., Harber M., Turtzo L.C., Shenouda C.N., Silverman E., gong Y., Qu B., Harburg L., Lu H., Wassermann E., and Diaz-Arrastia R. (2018). Imaging of cerebrovascular function in chronic traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 35, 1116–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Neil M., Carlson K., Storzbach D., Brenner L., Freeman M., Quiñones A., Motu'apuaka M., Ensley M., and Kansagara D. (2013). Complications of mild traumatic brain injury in veterans and military personnel: a systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, pp. 1–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang H., and Fitzpatrick J.M. (1992). A technique for accurate magnetic resonance imaging in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 11, 319–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yezhuvath U.S., Lewis-Amezcua K., Varghese R., Xiao G., and Lu H. (2009). On the assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity using hypercapnia BOLD MRI. NMR Biomed. 22, 779–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yezhuvath U.S., Uh J., Cheng Y., Martin-Cook K., Weiner M., Diaz-Arrastia R., van Osch M., and Lu H. (2012). Forebrain-dominant deficit in cerebrovascular reactivity in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 75–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landman B.A., Bogovic J.A., Carass A., Chen M., Roy S., Shiee N., Yang Z., Kishore B., Pham D., Bazin P.L., Resnick S.M., and Prince J.L. (2013). System for integrated neuroimaging analysis and processing of structure. Neuroinformatics 11, 91–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersson J.L.R., Skare S., and Ashburner J. (2003). How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 20, 870–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jenkinson M., Beckmann C.F., Behrens T.E.J., Woolrich M.W., and Smith S.M. (2012). FSL. Neuroimage 62, 782–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu H., Liu P., Yezhuvath U., Cheng Y., Marshall O., and Ge Y. (2014). MRI mapping of cerebrovascular reactivity via gas inhalation challenges. J. Vis. Exp. December 17. doi: 10.3791/52306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Smith S.M., Jenkinson M., Woolrich M.W., Beckmann C.F., Behrens T.E., Johansen-Berg H., Bannister P.R., De Luca M., Drobnjak I., Flitney D.E., Niazy R.K., Saunders J., Vickers J., Zhang Y., De Stefano N., Brady J.M., and Matthews P.M. (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23, Suppl. 1, S208–S219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woolrich M.W., Jbabdi S., Patenaude B., Chappell M., Makni S., Behrens T., Beckmann C., Jenkinson M., and Smith S.M. (2009). Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage 45, 1 Suppl., S173–S186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graham D.I., Adams J.H., and Doyle D. (1978). Ischaemic brain damage in fatal non-missile head injuries. J. Neurol. Sci. 39, 213–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graham D.I., Ford I., Adams J.H., Doyle D., Teasdale G.M., Lawrence A.E., and McLellan D.R. (1989). Ischaemic brain damage is still common in fatal non-missile head injury. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 52, 346–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rostami E., Engquist H., and Enblad P. (2014). Imaging of cerebral blood flow in patients with severe traumatic brain injury in the neurointensive care. Front. Neurol. 5, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez-Baeza A., Reina-de la Torre F., Poca A., Marti M., and Garnacho A. (2003). Morphological features in human cortical brain microvessels after head injury: a three-dimensional and immunocytochemical study. Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 273, 583–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cechetti F., Pagnussat A.S., Worm P. V., Elsner V.R., Ben J., da Costa M.S., Mestriner R., Weis S.N., and Netto C.A. (2012). Chronic brain hypoperfusion causes early glial activation and neuronal death, and subsequent long-term memory impairment. Brain Res. Bull. 87, 109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ding G., Jiang Q., Li L., Zhang L., Wang Y., Zhang Z.G., Lu M., Panda S., Li Q., Ewing J., and Chopp M. (2011). Cerebral tissue repair and atrophy after embolic stroke in rat: an MRI study of Erythropoietin therapy. J. Neurosci. Res. 88, 3206–3214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Promjunyakul N.O., Lahna D.L., Kaye J.A., Dodge H.H., Erten-Lyons D., Rooney W.D., and Silbert L.C. (2016). Comparison of cerebral blood flow and structural penumbras in relation to white matter hyperintensities: a multi-modal magnetic resonance imaging study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 36, 1528–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellis M.J., Ryner L.N., Sobczyk O., Fierstra J., Mikulis D.J., Fisher J.A., Duffin J., and Mutch W.A.C. (2016). Neuroimaging assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity in conclusion: current concepts, methodological considerations, and review of the literature. Front. Neurol. 7, 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravi H., Thomas B.P., Peng S.L., Liu H., and Lu H. (2016). On the optimization of imaging protocol for the mapping of cerebrovascular reactivity. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 43, 661–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halani S., Kwinta J.B., Golestani A.M., Khatamian Y.B., and Chen J.J. (2015). Comparing cerebrovascular reactivity measured using BOLD and cerebral blood flow MRI: The effect of basal vascular tension on vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive reactivity. Neuroimage 110, 110–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding G., Jiang Q., Li L., Zhang L., Zhang Z.G., Ledbetter K.A., Panda S., Davarani S.P., Athiraman H., Li Q., Ewing J.R., and Chopp M. (2008). Magnetic resonance imaging investigation of axonal remodeling and angiogenesis after embolic stroke in sildenafil-treated rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 28, 1440–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li L., Jiang Q., Zhang L., Ding G., Gang Z.Z., Li Q., Ewing J.R., Lu M., Panda S., Ledbetter K.A., Whitton P.A., and Chopp M. (2007). Angiogenesis and improved cerebral blood flow in the ischemic boundary area detected by MRI after administration of sildenafil to rats with embolic stroke. Brain Res. 1132, 185–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang R., Wang Y., Zhang L., Zhang Z., Tsang W., Lu M., Zhang L., and Chopp M. (2002). Sildenafil (Viagra) induces neurogenesis and promotes functional recovery after stroke in rats. Stroke 33, 2675–2680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang B., Sun L., Tian Y., Li Z., Wei H., Wang D., Yang Z., Chen J., Zhang J., and Jiang R. (2012). Effects of atorvastatin in the regulation of circulating EPCs and angiogenesis in traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 319, 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsumura M., Fukuda N., Kobayashi N., Umezawa H., Takasaka A., Matsumoto T., Yao E.H., Ueno T., and Negishi N. (2009). Effects of atorvastatin on angiogenesis in hindlimb ischemia and endothelial progenitor cell formation in rats. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 16, 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kenney K., Amyot F., Moore C., Haber M., Turtzo L.C., Shenouda C., Silverman E., Gong Y., Qu B.-X., Harburg L., Wassermann E.M., Lu H., and Diaz-Arrastia R. (2018). Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor potentiates cerebrovascular reactivity in chronic traumatic brain injury. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. July 3. doi: 10.1002/acn3.541. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]