Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Despite the fact that many older adults receive home or long-term care services, the effect of these care settings on hospital readmission is often overlooked. Efforts to reduce hospital readmissions, including capacity planning and targeting of interventions, require clear data on the frequency of and risk factors for readmission among different populations of older adults.

METHODS:

We identified all adults older than 65 years discharged from an unplanned medical hospital stay in Ontario between April 2008 and December 2015. We defined 2 preadmission care settings (community, long-term care) and 3 discharge care settings (community, home care, long-term care) and used multinomial regression to estimate associations with 30-day readmission (and death as a competing risk).

RESULTS:

We identified 701 527 individuals (mean age 78.4 yr), of whom 414 302 (59.1%) started in and returned to the community. Overall, 88 305 in dividuals (12.6%) were re admitted within 30 days, but this proportion varied by care setting combination. Relative to individuals returning to the community, those discharged to the community with home care (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.39–1.46) and those returning to long-term care (adjusted OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.27–1.43) had a greater risk of readmission, whereas those newly admitted to long-term care had a lower risk of readmission (adjusted OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.63–0.72).

INTERPRETATION:

In Ontario, about 40% of older people were discharged from hospital to either home care or long-term care. These discharge settings, as well as whether an individual was admitted to hospital from long-term care, have important implications for understanding 30-day readmission rates. System planning and efforts to reduce readmission among older adults should take into account care settings at both admission and discharge.

Thirty-day readmission rates are commonly used to assess health system performance and to guide resource allocation; they are also used as end points in studies of interventions designed to improve quality of care.1–3 Much of the research on 30-day readmission rates has focused on populations that are admitted to hospital from the community with subsequent return to the community. Although this group is useful for understanding readmissions among certain segments of the population, it overlooks users of home care and residential long-term care services, more specifically, frail older adults whose care poses one of the biggest challenges currently facing the health care system.

Much of the previous research on readmissions, including studies on population trends and risk prediction models, either excluded older adults discharged to home care or long-term care or did not account for the use of these services.1,4,5 The small number of studies that compared readmission rates across discharge settings have reported conflicting results.6–9 Even fewer studies have considered the care setting before hospital admission or the effects of a change in setting at discharge. As such, there is an important gap in our understanding of the frequency of the simple transition from the community to hospital and back to the community relative to that of other, more complicated transitions across care settings, and the impact of this on readmission rates. Furthermore, clinicians have little guidance about how to assess or reduce the risk of readmission for older adults admitted from and discharged to these care settings, and policy-makers have little evidence to inform system-level strategies designed to improve population health and use available resources efficiently.

Our objective was to describe and compare 30-day unplanned hospital readmissions among older adults characterized by their care setting both before and after hospital discharge. We hypothesized that a large proportion of older adults would experience a change in care setting after the hospital stay, that older adults with different care setting pathways would have different clinical and health service use profiles, and that older adults admitted from and discharged back to the community would have the lowest rate of readmission, even after adjustment for other variables. Given the limited data on readmissions that are available from other care settings, we could not anticipate how older adults discharged to home care and long-term care would differ. The information from this study will contribute to a better understanding of the extent to which complicated transitions to and from hospital influence re admission among older adults, which is essential for system planning, performance measurement, and the targeting and testing of interventions to improve transitions and reduce readmissions.

Methods

For this retrospective cohort study, we used health administrative data from multiple sectors in Ontario. Information on these data sources, including the Discharge Abstract Database, is provided in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.180290/-/DC1). Data were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES in Toronto.

Selection of study cohort

We identified all individuals aged 66 years and older who were discharged alive after a nonelective medical hospital admission between Apr. 1, 2008, and Dec. 31, 2015. For individuals with more than 1 discharge within the study period, we selected the first discharge. Hospital stays with evidence of transfer between institutions were treated as single episodes. Medical hospital admissions were identified using the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s case mix grouping (known as the CMG+ methodology).10 We excluded admissions associated with surgery, psychiatry, obstetrics or cancer therapy. We focused on medical admissions, to be consistent with other literature.9,11,12

Care settings

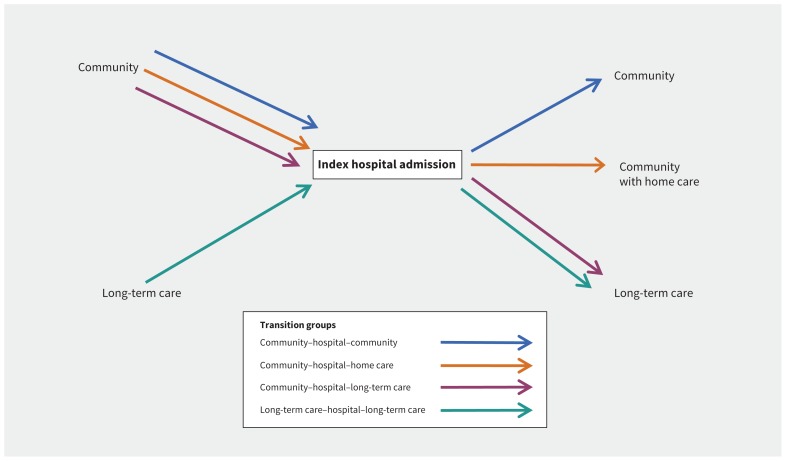

We created 4 mutually exclusive categories based on the combination of care settings before and after the index hospitalization (Figure 1): admission from and return to the community (C–C), admission from the community and return to the community with home care (C–H), admission from the community and discharge to long-term care (C–L), and admission from and return to long-term care (L–L). For individuals who started in long-term care, we considered only return to long-term care, because these people were unlikely to be discharged elsewhere. We considered an individual to have been discharged to home care or long-term care if we found evidence of either form of care within 14 days after discharge. We did not include home care as a care setting before hospital admission because we were unable to determine consistent use of home care services reliably, given the nature of these services and available data. We excluded individuals discharged to any rehabilitation setting because rehabilitation is likely to have different influences on readmission.

Figure 1:

Care setting combinations for patients admitted to hospital from the community or long-term care and discharged to various settings after the hospital stay.

Characteristics of study cohort

We characterized members of the cohort by demographic characteristics and chronic conditions that were present during the 5 years before the index hospital admission, specifically anxiety and depression, arthritis, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, diabetes mellitus, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, hypertension, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic heart disease, osteoporosis or osteopenia, and renal disease (with and without long-term dialysis). We characterized physician visits, emergency department visits and hospital admission in the year and in the 30 days before the index hospitalization, as well as home care use in the 30 days before hospitalization.

Index hospital admission

We estimated the total length of stay, in days, from the date of admission to the date of discharge (or from the initial admission to the final discharge if the patient was transferred during the hospitalization). We identified the most responsible diagnosis, defined as the diagnosis most responsible for the overall length of stay. We categorized these diagnoses according to case mix group,10 and then aggregated the case mix groups on the basis of clinical input, to reduce the number of categories. We identified days with alternate level of care (ALC), which refers to periods when an individual is considered to no longer require acute level services but cannot be discharged because appropriate care is not available elsewhere (such as when a long-term care bed is not available). In-hospital complications were defined as diagnoses that arose after admission.

Hospital readmissions

Each individual was followed from the discharge date for up to 30 days, during which time any nonelective admission to any hospital in Ontario or death was identified. If more than 1 readmission was detected, we used only the first. We characterized readmissions according to timing relative to index discharge, total length of stay, most responsible diagnosis, ALC days and readmission discharge disposition. We categorized discharge disposition as the same or a lower level of care (relative to before the readmission), a higher level of care or death.

Statistical analysis

For each combination of care settings, we used descriptive statistics to characterize baseline and index hospitalization variables, and to estimate the proportion of individuals who either were readmitted or died (without readmission) within 30 days after discharge. For those who were readmitted, we described the readmission. Estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To address competing risks, we created a multinomial outcome: readmission, death (without readmission) or neither within 30 days. We used a single multinomial model to quantify the effect of the care setting combination on the likelihood of each 30-day readmission and death, with C–C as the reference category. To address confounding, we included all baseline and index hospitalization variables that changed the unadjusted associations between care setting and either outcome by 10% or more. We used a generalized estimating equation to account for clustering within the index hospital. Final estimates were adjusted for age, sex, number of pre-existing chronic conditions, dementia, any emergency department visits in the previous 6 months, any nonelective hospital admissions in the previous year and index hospitalization variables (aggregated case mix groups, any ALC days, length of stay and in-hospital complications). We also adjusted for any home care visit within 30 days before the index hospitalization, because we did not have a pre-hospitalization home care group.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and Women’s College Hospital, Toronto.

Results

We identified a cohort of 701 527 individuals. The majority (414 302 or 59.1%) started in and returned to the community after the index hospital admission, whereas 221 169 (31.5%) were discharged with home care and 21 440 (3.1%) were newly admitted to long-term care.

The mean age for the cohort was 78.4 (standard deviation [SD] 8.0) years, 375 657 (53.5%) of cohort members were women, and 283 064 (40.3%) had 5 or more chronic conditions. In the year before the index admission, virtually everyone (685 372 [97.7%]) had visited a physician at least once, 331 168 (47.2%) had visited the emergency department, and 72 536 (10.3%) had been admitted to hospital.

Baseline variables differed by care setting combination (Table 1). Those who started in and returned to the community were the youngest and had the lowest proportion of women, whereas those discharged to long-term care were the oldest and had the highest proportion of women. Stark differences in preexisting chronic conditions emerged, with the greatest difference observed for dementia (from 11.6% for the C–C combination to 82.7% for the L–L combination). The C–H combination had the greatest frequency of emergency department visits in the year before the index admission, whereas the C–L combination had the greatest use of home care before hospital admission.

Table 1:

Characteristics of older Ontarians at time of discharge from first nonelective medical hospital admission (baseline), by care setting combination (Apr. 1, 2008, to Dec. 31, 2015)

| Characteristic | Care setting combination; no. of individuals and % of individuals (95% CI for %)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community to community n = 414 302 |

Community to community with home care n = 221 169 |

Community to long-term care n = 21 440 |

Long-term care to long-term care n = 44 616 |

|

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 76.6 ± 7.3 | 80.0 ± 8.0 | 84.2 ± 7.2 | 84.2 ± 7.8 |

| Age group, yr | ||||

| 66–69 | 88 485 21.4 (21.2–21.5) |

28 075 12.7 (12.6–12.8) |

821 3.8 (3.6–4.1) |

2573 5.8 (5.6–6.0) |

| 70–74 | 92 083 22.2 (22.1–22.4) |

33 072 15.0 (14.8–15.1) |

1491 7.0 (6.6–7.3) |

3104 7.0 (6.7–7.2) |

| 75–79 | 89 271 21.5 (21.4–21.7) |

40 931 18.5 (18.3–18.7) |

2934 13.7 (13.2–14.2) |

5556 12.5 (12.1–12.8) |

| 80–84 | 76 876 18.6 (18.4–18.7) |

49 091 22.2 (22.0–22.4) |

5121 23.9 (23.2–24.5) |

9575 21.5 (21.0–21.9) |

| 85–89 | 47 885 11.6 (11.4–11.7) |

42 806 19.4 (19.2–19.5) |

5881 27.4 (26.7–28.1) |

12 030 27.0 (26.5–27.5) |

| ≥ 90 | 19 702 4.8 (4.7–4.8) |

27 194 12.3 (12.2–12.4) |

5192 24.2 (23.6–24.9) |

11 778 26.4 (25.9–26.9) |

| Sex, female | 205 067 49.5 (49.3–49.7) |

127 511 57.7 (57.3–58.0) |

13 900 64.8 (63.8–65.9) |

29 179 65.4 (64.6–66.2) |

| Neighbourhood income quintile | ||||

| Lowest | 83 342 20.1 (20.0–20.2) |

49 817 22.5 (22.3–22.7) |

5551 25.9 (25.2–26.6) |

10 635 23.8 (23.4–24.3) |

| Highest | 79 871 19.3 (19.1–19.4) |

39 025 17.6 (17.5–17.8) |

3305 15.4 (14.9–16.0) |

7354 16.5 (16.1–16.9) |

| Pre-existing chronic conditions | ||||

| Any | 408 499 98.6 (98.3–98.9) |

219 871 99.4 (99.0–99.8) |

21 381 99.7 (98.4–100) |

44 552 99.9 (98.9–100) |

| Anxiety or depression | 129 617 31.3 (31.1–31.5) |

83 443 37.7 (37.5–38.0) |

10 227 47.7 (46.8–48.6) |

23 227 52.1 (51.4–52.7) |

| Arthritis | 252 524 61.0 (60.7–61.2) |

139 831 63.2 (62.9–63.6) |

12 797 59.7 (58.7–60.7) |

23 897 53.6 (52.9–54.2) |

| Cancer | 100 783 24.3 (24.2–24.5) |

76 715 34.7 (34.4–34.9) |

4652 21.7 (21.1–22.3) |

9284 20.8 (20.4–21.2) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 83 407 20.1 (20.0–20.3) |

50 907 23.0 (22.8–23.2) |

3721 17.4 (16.8–17.9) |

10 776 24.2 (23.7–24.6) |

| Congestive heart failure | 93 773 22.6 (22.5–22.8) |

64 041 29.0 (28.7–29.2) |

5527 25.8 (25.1–26.5) |

15 678 35.1 (34.6–35.7) |

| Dementia | 48 036 11.6 (11.5–11.7) |

58 250 26.3 (26.1–26.5) |

15 157 70.7 (69.6–71.8) |

36 897 82.7 (81.7–83.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 148 694 35.9 (35.7–36.1) |

85 597 38.7 (38.4–39.0) |

7033 32.8 (32.0–33.6) |

17 646 39.6 (39.0–40.1) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding, upper | 21 943 5.3 (5.2–5.4) |

9844 4.5 (4.4–4.5) |

762 3.6 (3.3–3.8) |

3767 8.4 (8.2–8.7) |

| Hypertension | 338 096 81.6 (81.3–81.9) |

184 739 83.5 (83.1–83.9) |

17 776 82.9 (81.7–84.1) |

36 460 81.7 (80.9–82.6) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 65 893 15.9 (15.8–16.0) |

40 611 18.4 (18.2–18.5) |

3748 17.5 (16.9–18.0) |

9136 20.5 (20.1–20.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 156 005 37.7 (37.5–37.8) |

72 955 33.0 (32.7–33.2) |

5581 26.0 (25.3–26.7) |

13 851 31.0 (30.5–31.6) |

| Osteoporosis or osteopenia | 106 986 25.8 (25.7–26.0) |

76 025 34.4 (34.1–34.6) |

9115 42.5 (41.6–43.4) |

19 484 43.7 (43.1–44.3) |

| Renal disease with long-term dialysis | 4685 1.1 (1.1–1.2) |

4024 1.8 (1.8–1.9) |

171 0.8 (0.7–0.9) |

583 1.3 (1.2–1.4) |

| Renal disease without long-term dialysis | 53 456 12.9 (12.8–13.0) |

37 149 16.8 (16.6–17.0) |

3188 14.9 (14.4–15.4) |

8089 18.1 (17.7–18.5) |

| No. of pre-existing conditions, mean ± SD | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 5.1 ± 1.9 |

| Health service use before index admission | ||||

| Any physician visit in previous year | 404 272 97.6 (97.3–97.8) |

216 437 97.9 (97.5–98.3) |

20 233 94.4 (93.1–95.7) |

44 430 99.6 (98.7–100.0) |

| Any ED visit in previous year | 184 516 44.5 (44.3–44.7) |

117 421 53.1 (52.8–53.4) |

10 763 50.2 (49.3–51.2) |

18 468 41.4 (40.8–42.0) |

| Any ED visit in previous 30 d | 73 274 17.7 (17.6–17.8) |

50 369 22.8 (22.6–23.0) |

4667 21.8 (21.1–22.4) |

5588 12.5 (12.2–12.9) |

| Any hospital admission in previous year | 32 873 7.9 (7.8–8.0) |

29 495 13.3 (13.2–13.5) |

2142 10.0 (9.6–10.4) |

8026 18.0 (17.6–18.4) |

| Any hospital admission in previous 30 d | 7154 1.7 (1.7–1.8) |

7295 3.3 (3.2–3.4) |

446 2.1 (1.9–2.3) |

1452 3.3 (3.1–3.4) |

| Home care use in previous 30 d | 13 973 3.4 (3.3–3.4) |

98 786 44.7 (44.4–44.9) |

10 903 50.9 (49.9–51.8) |

3997 9.0 (9.0–9.2) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, ED = emergency department, SD = standard deviation.

Except where indicated otherwise.

Gastrointestinal conditions were the most common reason for hospital admission among those in the C–C and C–H combinations (14.5% and 8.6%, respectively), stroke was the most common reason among those in the C–L combination (7.5%), and pneumonia or another respiratory condition was the most common reason among those in the L–L combination (15.5%) (Table 2). Dementia, which was not among the 10 most common reasons overall, was the most common reason for admission within the C–L combination (3521/21 440 [16.4%], compared with 9432/701 527 [1.3%] overall). Individuals in the C–L combination had the longest mean length of stay (56.9 [SD 70.6] d), the greatest proportion in hospital for 14 days or longer (83.6%), the highest proportion with ALC days (85.4%) and the longest mean time with ALC status (48.7 [SD 69.0] d).

Table 2:

Features of the index unplanned medical hospital admission for older Ontarians, by care setting combination (Apr. 1, 2008, to Dec. 31, 2015)

| Feature of hospital admission | Care setting combination; no. of individuals and % of individuals (95% CI for %)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community to community n = 414 302 |

Community to community with home care n = 221 169 |

Community to long-term care n = 21 440 |

Long-term care to long-term care n = 44 616 |

|

| Top 10 aggregated CMGs (based on overall population) | ||||

| Gastroenteritis, bowel obstruction, other GI problem | 60 159 14.5 (14.4–14.6) |

18 951 8.6 (8.4–8.7) |

675 3.1 (2.9–3.4) |

5167 11.6 (11.3–11.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 47 031 11.4 (11.2–11.4) |

9890 4.5 (4.4–4.6) |

509 2.4 (2.2–2.6) |

1843 4.1 (3.9–4.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25 273 6.1 (6.0–6.2) |

12 262 5.5 (5.4–5.6) |

522 2.4 (2.2–2.6) |

2693 6.0 (5.8–6.3) |

| Pneumonia or other respiratory infection | 22 955 5.5 (5.5–5.6) |

12 940 5.9 (5.7–6.0) |

960 4.5 (4.2–4.8) |

6907 15.5 (15.1–15.9) |

| Heart failure | 20 301 4.9 (4.8–5.0) |

12 007 5.4 (5.3–5.5) |

657 3.1 (2.8–3.3) |

2227 5.0 (4.8–5.2) |

| Arrhythmia | 26 458 6.4 (6.3–6.4) |

6099 2.8 (2.7–2.8) |

266 1.2 (1.1–1.4) |

958 2.1 (2.0–2.3) |

| Stroke | 18 124 4.4 (4.3–4.4) |

9801 4.4 (4.3–4.5) |

1598 7.5 (7.1–7.8) |

1761 3.9 (3.8–4.1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 11 890 2.9 (2.8–2.9) |

9227 4.2 (4.1–4.3) |

755 3.5 (3.3–3.8) |

4360 9.8 (9.5–10.1) |

| Cardiovascular problem | 16 616 4.0 (4.0–4.1) |

8374 3.8 (3.7–3.9) |

286 1.3 (1.2–1.5) |

901 2.0 (1.9–2.2) |

| Cancer | 10 742 2.6 (2.5–2.6) |

13 690 6.2 (6.1–6.3) |

369 1.7 (1.5–1.9) |

611 1.4 (1.3–1.5) |

| Length of stay, d, mean ± SD | 4.8 (7.7) | 9.4 (11.6) | 56.9 (70.6) | 7.3 (13.6) |

| Length of stay category, d | ||||

| 1–3 | 220 555 53.2 (53.0–53.5) |

58 238 26.3 (26.1–26.5) |

680 3.2 (2.9–3.4) |

15 848 35.5 (35.0–36.1) |

| 4–6 | 111 322 26.9 (26.7–27.0) |

55 731 25.2 (25.0–25.4) |

712 3.3 (3.1–3.6) |

12 833 28.8 (28.3–29.3) |

| 7–10 | 49 728 12.0 (11.9–12.1) |

46 475 21.0 (20.8–21.2) |

1132 5.3 (5.0–5.6) |

8366 18.8 (18.3–19.2) |

| 11–13 | 13 414 3.2 (3.2–3.3) |

18 837 8.5 (8.4–8.6) |

985 4.6 (4.3–4.9) |

2942 6.6 (6.4–6.8) |

| ≥ 14 | 19 283 4.7 (4.6–4.7) |

41 888 18.9 (18.8–19.1) |

17 931 83.6 (82.4–84.9) |

4627 10.4 (10.1–10.7) |

| Alternate level of care (ALC) | ||||

| Any ALC time | 10 143 2.4 (2.4–2.5) |

23 507 10.6 (10.5–10.8) |

18 303 85.4 (84.1–86.6) |

1881 4.2 (4.0–4.4) |

| Time in ALC, d, mean ± SD | 14.0 ± 30.1 | 11.4 ± 16.9 | 48.7 ± 69.0 | 23.6 ± 50.8 |

| In-hospital complication | 25 617 6.2 (6.1–6.3) |

29 882 13.5 (13.4–13.7) |

6747 31.5 (30.7–32.2) |

5013 11.2 (10.9–11.5) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, CMG = case mix group, GI = gastrointestinal, SD = standard deviation.

Except where indicated otherwise.

The overall frequency of 30-day readmission was 12.6%, but frequency varied by setting combination: 10.6% of those returning to the community, 16.8% of those receiving home care, 8.4% of those newly admitted to long-term care and 12.4% of those returning to long-term care (Table 3). Overall, 2.3% of the cohort died within 30 days of discharge, and this too varied by setting.

Table 3:

All unplanned hospital readmissions among older Ontarians, within 30 days of discharge from index medical hospital admission, by care setting combination (Apr. 1, 2008, to Dec. 31, 2015)

| Variable | Care setting combination; no. of individuals and % of individuals (95% CI for %)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community to community | Community to community with home care | Community to long-term care | Long-term care to long-term care | |

| Individuals in care setting combination | n = 414 302 | n = 221 169 | n = 21 440 | n = 44 616 |

| Died without readmission within 30 d of discharge | 3526 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

6018 2.7 (2.6–2.8) |

851 4.0 (3.7–4.2) |

5904 13.2 (12.9–13.6) |

| Readmitted within 30 d of discharge | 43 731 10.6 (10.5–10.6) |

37 251 16.8 (16.7–17.0) |

1793 8.4 (8.0–8.8) |

5530 12.4 (12.1–12.7) |

| Among those with readmission | n = 43 731 | n = 37 251 | n = 1793 | n = 5530 |

| Time to readmission, d, mean ± SD | 11.5 ± 8.6 | 12.4 ± 8.4 | 13.3 ± 8.8 | 11.5 ± 8.5 |

| Time to readmission category, d | ||||

| 0 | 1040 2.4 (2.2–2.5) |

344 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

20 1.1 (0.7–1.7) |

65 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| 1–3 | 9042 20.7 (20.2–21.1) |

5718 15.3 (14.9–15.7) |

280 15.6 (13.8–17.6) |

1136 20.5 (19.4–21.8) |

| 4–7 | 8387 19.2 (18.8–19.6) |

7495 20.1 (19.7–20.6) |

300 16.7 (14.9–18.7) |

1107 20.0 (18.9–21.2) |

| 8–14 | 10 333 23.6 (23.2–24.1) |

9589 25.7 (25.2–26.3) |

431 24.0 (21.8–26.4) |

1324 23.9 (22.7–25.3) |

| 15–21 | 7500 17.2 (16.8–17.5) |

7223 19.4 (18.9–19.8) |

355 19.8 (17.8–22.0) |

961 17.4 (16.3–18.5) |

| 22–30 | 7429 17.0 (16.6–17.4) |

6882 18.5 (18.0–18.9) |

407 22.7 (20.5–25.0) |

937 16.9 (15.9–18.1) |

| Top 10 aggregated CMGs† at time of readmission | ||||

| Surgical | 7280 16.6 (16.3–17.0) |

3716 10.0 (9.7–10.3) |

173 9.6 (8.3–11.2) |

385 7.0 (6.3–7.7) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2548 5.8 (5.6–6.1) |

1171 3.1 (3.0–3.3) |

44 2.5 (1.8–3.2) |

208 3.8 (3.3–4.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2049 4.7 (4.5–4.9) |

1535 4.1 (3.9–4.3) |

97 5.4 (4.4–6.6) |

279 5.0 (4.5–5.7) |

| Pneumonia or other respiratory infection | 1400 3.2 (3.0–3.4) |

1535 4.1 (3.9–4.3) |

178 9.9 (8.5–11.5) |

765 13.8 (12.9–14.8) |

| Heart failure | 3194 7.3 (7.1–7.6) |

2572 6.9 (6.6–7.2) |

121 6.7 (5.6–8.1) |

403 7.3 (6.6–8.0) |

| Arrhythmia | 1727 3.9 (3.8–4.1) |

654 1.8 (1.6–1.9) |

22 1.2 (0.8–1.9) |

90 1.6 (1.3–2.0) |

| Stroke | 1277 2.9 (2.8–3.1) |

802 2.2 (2.0–3.2) |

42 2.3 (1.7–3.2) |

119 2.2 (1.8–2.6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 780 1.8 (1.7–1.9) |

1117 3.0 (2.8–3.2) |

116 6.5 (5.3–7.8) |

410 7.4 (6.7–8.2) |

| Cardiovascular problem | 1528 3.5 (3.3–3.7) |

1176 3.2 (3.0–3.3) |

29 1.6 (1.1–2.3) |

131 2.4 (2.0–2.8) |

| Cancer | 2352 5.4 (5.2–5.6) |

2548 6.8 (6.6–7.1) |

29 1.6 (1.1–2.3) |

65 1.2 (0.9–1.5) |

| Diagnostic concordance between index admission and readmission | ||||

| Same CMG | 9572 21.9 (21.4–22.3) |

7117 19.1 (18.7–19.5) |

193 10.8 (9.7–12.4) |

1076 19.5 (18.3–20.7) |

| Same aggregated CMGs† | 3163 7.2 (7.0–7.5) |

1858 5.0 (4.8–5.2) |

35 2.0 (1.4–2.7) |

321 5.8 (5.2–6.5) |

| Different aggregated CMGs† | 30 996 70.9 (70.1–71.7) |

28 276 75.9 (75.0–76.8) |

1565 87.3 (83.0–91.7) |

4133 74.7 72.5–77.0) |

| Among those with readmission | n = 43 731 | n = 37 251 | n = 1793 | n = 5530 |

| Length of readmission stay, d, mean ± SD | 11.2 ± 20.2 | 13.4 ± 23.3 | 12.4 ± 39.7 | 9.6 ± 25.3 |

| Length of stay category for readmission, d | ||||

| 1–3 | 13 165 30.1 (29.6–30.6) |

9136 24.5 (24.0–25.0) |

524 29.2 (26.8–31.8) |

1616 29.2 (27.8–30.7) |

| 4–6 | 10 033 22.9 (22.5–23.4) |

8154 21.9 (21.4–22.4) |

457 25.5 (23.2–27.9) |

1460 26.4 (25.1–27.8) |

| 7–10 | 7639 17.5 (17.1–17.9) |

6909 18.5 (18.1–19.0) |

341 19.0 (17.0–21.1) |

1113 20.1 (18.9–21.3) |

| 11–13 | 3237 7.4 (7.2–7.7) |

2989 8.0 (7.7–8.3) |

126 7.0 (5.8–8.4) |

393 7.1 (6.4–7.9) |

| ≥ 14 | 9657 22.1 (21.6–22.5) |

10 063 27.0 (26.5–27.5) |

345 19.2 (17.3–21.4) |

948 17.1 (16.1–18.3) |

| Any ALC time during readmission | 4554 10.4 (10.1–10.7) |

7166 19.2 (18.8–19.7) |

259 14.4 (12.7–16.3) |

340 6.1 (5.5–6.8) |

| Readmitted to same hospital as for index admission | 36 485 83.4 (82.6–84.3) |

32 021 86.0 (85.0–86.9) |

1231 68.7 (64.9–72.6) |

4743 85.8 (83.3–88.2) |

| Outcome, as level of care at discharge or death | ||||

| Returned to same site or lower level of care | 26 532 60.7 (59.9–61.4) |

25 120 67.4 (66.6–68.3) |

1336 74.5 (70.6–78.6) |

4324 78.2 (75.9–80.6) |

| Moved to higher level of care | 12 625 28.9 (28.4–29.4) |

5158 13.8 (13.5–14.2) |

62 3.5 (2.6–4.4) |

98 1.8 (1.4–2.2) |

| Died | 4574 10.5 (10.2–10.8) |

6973 18.7 (18.3–19.2) |

395 22.0 (19.9–24.3) |

1108 20.0 (18.9–21.2) |

Note: ALC = alternate level of care, CI = confidence interval, CMG = case mix group, SD = standard deviation.

Except where indicated otherwise.

Groupings of related CMGs (based on overall population), where the CMGs were defined according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s CMG+ methodology.10

The mean time between the index hospitalization and re admission was 11.9 (SD 8.5) days, with little difference by setting combination. Readmissions were longer than index hospitalizations for all combinations except C–L; this finding was driven by an increase in the proportion whose stay was 14 days or longer. Nearly 20% of those in the C–H combination had ALC days during the readmission. Ultimately, 10.5% of individuals in the C–C combination died during the readmission, compared with about 20% in the other setting combinations.

Following adjustment for demographic, clinical and health service use variables, including prior home care, we found that the C–H and L–L combinations had an increased likelihood, relative to the C–C combination, of 30-day readmission (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.43, 95% CI 1.39–1.46, and adjusted OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.27–1.43, respectively), and the C–L combination had a reduced likelihood (adjusted OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.63–0.72) (Table 4). Full model results are presented in Appendix 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.180290/-/DC1).

Table 4:

Odds ratios for 30-day unplanned hospital readmission and death, by care setting combination, among older adults in Ontario

| Care setting before index admission | Care setting after index admission | OR for 30-day readmission (95% CI) | OR for death (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted* | Unadjusted | Adjusted* | ||

| Community | Community | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

|

| |||||

| Community with home care | 1.76 (1.72–1.80) | 1.43 (1.39–1.46) | 3.52 (2.97–4.18) | 1.67 (1.31–2.12) | |

|

| |||||

| Long-term care | 0.80 (0.74–0.86) | 0.68 (0.63–0.72) | 4.71 (3.81–5.83) | 1.05 (0.74–1.48) | |

|

| |||||

| Long-term care | Long-term care | 1.40 (1.31–1.49) | 1.35 (1.27–1.43) | 18.52 (15.39–22.29) | 13.05 (10.85–15.69) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio, ref = reference.

Adjusted for age categories, sex, pre-existing chronic conditions (total number, dementia), any visit to the emergency department within 6 months before index hospital admission, any nonelective hospital admission within 1 year before index admission, any home care use in the 30 days before index hospital admission, case mix group at index hospital admission, length of index hospital stay (log), any alternate-level-of-care days during index hospital stay and any in-hospital complications during index hospital stay.

Interpretation

In this large, population-based cohort of older adults with an unplanned medical hospitalization, 31.5% were discharged to home care and 9.5% to long-term care (6.4% returning to long-term care and 3.1% newly admitted). Although most patients had a relatively simple transition, from the community to hospital and back to the community, a substantial proportion experienced more complicated transitions. These more complicated transitions have important resource implications that are directly related to the costs of home care and long-term care, but our work also shows that they are associated with important differences in terms of hospital readmission. Nearly 13% of the cohort was readmitted within 30 days after discharge, but this proportion varied by a factor of 2 when we considered the care setting before and after hospitalization. The spectrum of our results, from clinical profiles through service use patterns and outcomes, further shows that fundamental shortcomings in the health system’s ability to meet older adults’ needs, particularly those with dementia, manifest as frequent use of acute care, including readmissions, prolonged hospital stays with extended ALC periods and “non-acute” reasons for hospital admission.

Fundamental to a strong care system for older adults is sufficient access to appropriate home and long-term care services.13 We found that older adults discharged with home care were the most likely to be readmitted and, when they were readmitted, experienced the longest stays with the greatest frequency of ALC days. Others have suggested that mismatches between recipient needs and home care service provision result in poor outcomes,9 and a recent study suggested that associations between home care and emergency department use may result from the limited scope of home care services and lack of integration with primary care.14

Individuals who started in the community and were discharged to long-term care had the lowest likelihood of hospital readmission, which suggests that they were in the appropriate care setting but that the path to long-term care was marked by frequent acute care use, very long hospital stays and lengthy ALC periods. Individuals admitted from and discharged to long-term care had an increased likelihood of readmission. Some evidence suggests that long-term care residents are prematurely discharged from hospital because providers have little experience in long-term care and make erroneous assumptions about available resources.15 Although this issue is separate from the need for enhanced home and long-term care services, it is a reminder that improved management of frail older adults in the hospital is an important component of any comprehensive care strategy for older adults.

Quality end-of-life care, in any setting, is also critical to such a strategy. Among those readmitted from home care or long-term care, about 20% died during the readmission. The frequency of death following repeated transitions is concerning. Preferences for death at home, or in a home-like setting, over death in the hospital have been well documented,16 as has the burden of hospital admissions at the end of life.17 Quality end-of-life care reduces symptom burden and hospital transfers that are not desired by patients.

Finally, our data show the value of considering the care setting in risk assessment. The developers of clinical risk tools, such as the LACE+ index,18 did not account for out-of-hospital care setting, but it is clear from our findings that this important measurable factor is a predictor of readmission. Clinicians should be aware of patients’ care setting before admission and any change at discharge. Thirty-day readmission models are often used to compare the quality of care between hospitals, but this variable may also be affected by the omission of pre- and post-hospitalization care setting. Even after rigorous risk adjustment, care settings were strongly associated with 30-day readmission, which has implications for model validity, particularly when discharge patterns to home care, long-term care and other settings differ across hospitals.

Limitations

This study had limitations. Although we adjusted for many variables, we lacked data on measures such as physical or cognitive function and caregiver availability; however, we were able to adjust for dementia and other factors associated with declining function. Smaller studies have shown that physical function has a moderate influence on readmission,19,20 but it is difficult to know how this would translate to our cohort. That such measures are not routinely collected poses substantial barriers to implementing and monitoring a care system for older adults. We could not capture home care that was paid for privately. Nonetheless, we still found very large differences between the groups who did and did not receive publicly funded home care.

Conclusion

In this large cohort of older adults who had been admitted to hospital, we found that 40% had been discharged to either home care or long-term care and that the discharge setting, coupled with the prior care setting, had important implications for understanding 30-day hospital readmissions. Health system planning and strategies to reduce readmissions among older adults should take into account the care setting both before admission and at discharge. Furthermore, by contextualizing hospitalization within these care settings, our findings suggest an approach to understanding readmissions as a signal of the health system’s preparedness for the aging population.

Footnotes

Visual abstract available at: www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.180290/-/DC2

Competing interests: Chaim Bell is a medical consultant with the Policy and Innovations Branch of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Andrea Gruneir conceived of and designed the study and analysis plan, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. Kinwah Fung contributed to the design of the study and analysis plan, conducted the analyses and revised the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. Hadas Fischer contributed to the design of the study and analysis plan and revised the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. Susan Bronskill, Chaim Bell and Irfan Dhalla contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of the data analysis and revised the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. Dilzayn Panjwani contributed to the analysis plan and revised the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. Paula Rochon contributed to the conception and design of the study and revised the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. Geoff Anderson contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to interpretation of the data analysis and revised the manuscript for critically important intellectual content. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This research was funded by the Institute for Health Services and Policy Research (grant FRN 119330), Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). Andrea Gruneir is funded by a CIHR New Investigator Award. Paula Rochon holds the Retired Teachers of Ontario/ERO Chair in Geriatric Medicine.

Disclaimers: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the opinions and conclusions of Health Quality Ontario. No endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1.van Walraven C, Jennings A, Taljaard M, et al. Incidence of potentially avoidable urgent readmissions and their relation to all-cause urgent readmissions. CMAJ 2011;183:E1067–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berenson RA, Paulus RA, Kalman NS. Medicare’s readmissions-reduction program — a positive alternative. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1364–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhalla IA, O’Brien T, Morra D, et al. Effect of a postdischarge virtual ward on readmission or death for high-risk patients. JAMA 2014;312:1305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruneir A, Dhalla IA, van Walraven C, et al. Unplanned readmissions after hospital discharge among patients identified as being at high risk for readmission using a validated predictive algorithm. Open Med 2011;5:e104–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah T, Churpek MM, Coca Perraillon M, et al. Understanding why patients with COPD get readmitted: a large national study to delineate the Medicare population for the readmissions penalty expansion. Chest 2015;147:1219–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novotny NL, Anderson MA. Prediction of early readmission in medical inpatients using the Probability of Repeated Admission instrument. Nurs Res 2008;57:406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corrigan JM, Martin JB. Identification of factors associated with hospital re admission and development of a predictive model. Health Serv Res 1992;27: 81–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camberg LC, Smith NE, Beaudet M, et al. Discharge destination and repeat hospitalizations. Med Care 1997;35:756–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CMG+ [Case Mix Groups+ methodology]. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2015. Available: www.cihi.ca/en/cmg (accessed 2018 Feb. 28). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindenauer PK, Normand SLT, Drye EE, et al. Development, validation, and results of a measure of 30-day readmission following hospitalization for pneumonia. J Hosp Med 2011;6:142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan PS, et al. Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:587–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The state of seniors health care in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 2016. Available: www.cma.ca/En/Lists/Medias/the-state-of-seniors-health-care-in-canada-september-2016.pdf (accessed 2018 Sept. 4). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones A, Schumacher C, Bronskill SE, et al. The association between home care visits and same-day emergency department use: a case–crossover study. CMAJ 2018;190:E525–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:533–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruneir A, Mor V, Weitzen S, et al. Where people die: a multilevel approach to understanding influences on site of death in America. Med Care Res Rev 2007; 64:351–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter HE, Winch S, Barnett AG, et al. Incidence, duration and cost of futile treatment in end-of-life hospital admissions to three Australian public-sector tertiary hospitals: a retrospective multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Walraven C, Wong J, Forster AJ. LACE+ index: extension of a validated index to predict early death or urgent readmission after hospital discharge using administrative data. Open Med 2012;6:e80–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, et al. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:559–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Depalma G, Xu H, Covinsky KE, et al. Hospital readmission among older adults who return home with unmet need for ADL disability. Gerontologist 2013;53:454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]