Abstract

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of depression in patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and to identify sociodemographic, clinical and psychological factors associated with depression in this population. Additionally, we examine the annual incidence rate of depression among patients with T2DM.

Methods

We performed a large prospective cohort study of patients with T2DM from the Madrid Diabetes Study. The first recruitment drive included 3443 patients. The second recruitment drive included 727 new patients. Data have been collected since 2007 (baseline visit) and annually during the follow-up period (since 2008).

Results

Depression was prevalent in 20.03% of patients (n=592; 95% CI 18.6% to 21.5%) and was associated with previous personal history of depression (OR 6.482; 95% CI 5.138 to 8.178), mental health status below mean (OR 1.423; 95% CI 1.452 to 2.577), neuropathy (OR 1.951; 95% CI 1.423 to 2.674), fair or poor self-reported health status (OR 1.509; 95% CI 1.209 to 1.882), treatment with oral antidiabetic agents plus insulin (OR 1.802; 95% CI 1.364 to 2.380), female gender (OR 1.333; 95% CI 1.009 to 1.761) and blood cholesterol level (OR 1.005; 95% CI 1.002 to 1.009). The variables inversely associated with depression were: being in employment (OR 0.595; 95% CI 0.397 to 0.894), low physical activity (OR 0.552; 95% CI 0.408 to 0.746), systolic blood pressure (OR 0.982; 95% CI 0.971 to 0.992) and social support (OR 0.978; 95% CI 0.963 to 0.993). In patients without depression at baseline, the incidence of depression after 1 year of follow-up was 1.20% (95% CI 1.11% to 2.81%).

Conclusions

Depression is very prevalent among patients with T2DM and is associated with several key diabetes-related outcomes. Our results suggest that previous mental status, self-reported health status, gender and several diabetes-related complications are associated with differences in the degree of depression. These findings should alert practitioners to the importance of detecting depression in patients with T2DM.

Keywords: depression; diabetes mellitus, type 2; self-care; cohort studies

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Time between both telephone interviews for depression screening was too short (12 months), making it difficult to compare cumulative incidence rates with those of other studies.

We preferred to exclude antidepressant agents from our combined variable for depression, because the antidepressants can be prescribed for diseases other than depression (ie, sleeping disorders, migraine, neuropathic pain, obsessive-compulsive disorders, anxiety/panic disorder).

In order to compare our findings with multivariable models from different studies, we may have adjusted variables unnecessarily. However, fortunately, overadjustment was avoided (changes >20% between crude and adjusted SE, data not shown).

The strengths of our study include its prospective design, which ensured that measurement of risk factors preceded the development of depression, and the assessment of information on potentially confounding variables, which reduces potential selection and confusion biases.

We also used an assessment of depression based on MINI V.5.0, which was completed with the patient’s general practitioner who used his/her clinical judgement to determine whether the patient’s symptoms and signs were compatible with a depressive disorder. Therefore, self-reported diagnosis was avoided.

Introduction

Currently, an estimated 8%–9% adults worldwide have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and a substantial increase in prevalence over time has been observed.1 The prevalence of T2DM in the Spanish population is even higher (13.8%).2

Previous studies have shown that coexistence of mental disorders such as depression is considerably more frequent in people with T2DM than in the overall population,3 4 with a prevalence ranging from 15% to 24%5 and an incidence rate of depression during the first year after initiation of oral antidiabetic treatment of 12.61 per 1000 person-years.6 The coexistence of diabetes and mental disorders has a strong impact on the patient, with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), all-cause mortality7 and cardiovascular mortality,7 especially as a result of cardiovascular complications of T2DM.8 In addition, patients with diabetes and mental disorders show poorer compliance with treatment recommendations than patients with T2DM without depression, and more frequently have cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyle and poor glycaemic control,9 which can impact on their health-related quality of life.10

To our knowledge, research on common mental disorders affecting patients with T2DM is scarce in Spain.11–13 In a recent cross-sectional study on patients with T2DM, Alonso-Morán et al14 reported that 9.8% of patients were diagnosed with depression (5.2% men and 15.1% women) and in a study by Nicolau et al,12 27.2% of patients had symptoms of depression. However, in these studies, data collection was often based on health surveys11 15 or self-reported scales,12 16 which yielded heterogeneous data. Thus, mental disorders have not been assessed using a clinical interview as the ‘gold standard’.

The aims of the present study were to estimate the prevalence of depression in patients diagnosed with T2DM, and to identify sociodemographic, clinical and psychological factors associated with the occurrence of depression in this population. Additionally, we examine the 1 year incidence rate of depression among patients with T2DM.

Material and methods

Design and participants

The Madrid Diabetes Study (MADIABETES Study) is a large prospective cohort study of various clinical and psychosocial aspects of outpatients with T2DM living in the metropolitan area of Madrid, Spain. The first recruitment drive in 2007 enrolled 3443 outpatients with T2DM from the 56 participating primary healthcare centres (PHCCs). Patients were selected by simple random sampling by participating general practitioners (n=131) based on the list of patients with a diagnosis of T2DM in their computerised clinical records (CCRs). A more complete description of this methodology can be found elsewhere.17

Reasons for not continuing till completion were leaving the participating PHCC, death or dropout. Furthermore, the dynamic character of the MADIABETES cohort, that is, new participants could enter over time, helped prevent loss of the study population. Therefore, at the end of 2010, a second recruitment drive involving 41 PHCCs included 727 new patients.

The inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of T2DM in the CCR (code T90 of the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2)),18 age ≥30 years, visit to a PHCC at least twice in the previous year, and agreement to take part in the study providing written informed consent. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus, being in an institution, inability to understand Spanish, severe chronic diseases or significant physical or psychological disabilities that might invalidate informed consent or interviews (according to clinical judgement), legal incompetence or legal guardianship, and participation in clinical trials.

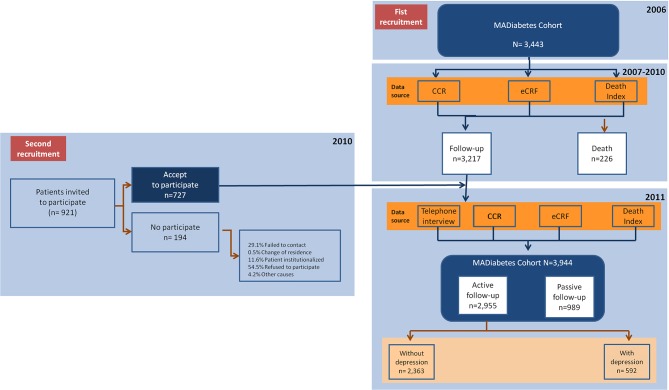

For the purpose of evaluating the prevalence of depression (DIAbetes and DEpression in MAdrid (DIADEMA) Study), we included those patients who participated in the interview process conducted between 1 January 2011 and 31 December 2011. Furthermore, to estimate the annual incidence of depression, the data from the second interview were included. The original protocol of the study was published in advance.19 Therefore, for the main variable the MADIABETES cohort included a total of 2955 patients (see the flow diagram in figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart. CCR, computerised clinical records; MADIABETES cohort, Madrid diabetes cohort.

Patient and public involvement

Major depression is prevalent among patients with diabetes, especially older adults, and is a risk factor for self-care, complications and death. Therefore, our research question focuses on screening for depressive symptoms in all patients with diabetes, with particular emphasis on those with a self-reported history of depression. We use age-appropriate depression screening measures and are aware that further evaluation will be necessary for individuals with a positive result. Treatment is prescribed accordingly.

Patients were not involved in the design, recruitment or conduct of the study. We report our results annually at a specific meeting, to which we invited the participating general practitioners and all the patients included in the MADIABETES cohort.

Source of data

To achieve the goal of the MADIABETES Study, data collection began in 2007 (baseline visit) and was then collected annually during the follow-up period (since 2008). Four data collection strategies were combined.

First, data concerning disease episodes (coded in ICPC-2),18 prescription of medication (coded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system), laboratory results, anthropometric variables and use of care facilities were obtained from the CCR. The CCR for primary healthcare in the Madrid Health Service was administered by the OMI-AP software. CCR registration is continuously updated in PHCC under routine clinical practice conditions, and once a year, data are transferred to our central database.

Second, the general practitioner of each participating patient collected information about morbidity and mortality, under routine clinical practice conditions using an electronic case report form (hosted on the website www.madiabetes.com). All general practitioners received training to standardise their knowledge of project objectives, data collection techniques and fieldwork procedures.

Third, 2011 onwards, all patients were invited each year to undergo an interview to provide sociodemographic and lifestyle data, determinants of health and psychosocial characteristics. Data were collected using a previously standardised protocol through a telephone interview with a clinical psychologist trained in the evaluation procedure of the study. Lastly, the vital status of the patients was ascertained from two mortality records: Índice Nacional de Defunciones (https://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/IND_TipoDifusion.htm) and Instituto Nacional de Estadística (http://www.ine.es). The latter indicates the underlying cause of death recorded on the death certificates, which is coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10).20

Variables

The primary outcome variable was depression. The diagnosis of depression was considered a combined variable, as suggested by other authors,21 consisting of a diagnosis based on the module of the major depressive disorder of MINI V.5.0.0.22 Following an interview by a trained psychologist, the diagnosis was made with the patient’s general practitioner who used his/her clinical judgement to determine whether the patient’s symptoms and signs were compatible with a depressive disorder.

The MINI is a short and efficient diagnostic interview to diagnose mental disorders; it was used in its Spanish version.23

The other psychosocial variables evaluated included the following:

A personal history of psychiatric disorder if the patient reported a positive response to the question: ’Has a clinician ever diagnosed you as having any psychiatric disorder?'. Alternatively, patients could have been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder before the last 12-month interval, as coded in the CCR.

A family history of psychiatric disorder was registered if the patient reported a positive response to the question: ‘Has any family member (first-degree relatives) ever been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder?’.

Anxiety disorder was defined based on the module of generalised anxiety disorder of the MINI23 and according to clinical judgement.

Social support, such as network size, was assessed based on the question: ’About how many close friends and close relatives do you have (people you feel at ease with and can talk to about what is on your mind)?', which corresponds to the first item of the Medical Outcomes Study-Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS).24

Health-related quality of life was measured using the SF-12 questionnaire, a composite of 12 items that assess eight dimensions of health: physical functioning, physical role, general health, body pain, vitality, social functioning, emotional role and mental health.25 The SF-12 measures various aspects of physical and mental health, from which physical and mental summary scores are computed using the scores of 12 questions. The score ranges from 0 to 100, where a 0 indicates the lowest level of health and 100 indicates the highest level of health. Both Physical and Mental Health Composite Scales combine the 12 items in such a way that they compare with a national norm (mean score of 50.0 and a SD of 10.0).

Insomnia was assessed using the Spanish version of the eight-item Athens Insomnia Scale26 which is a self-reported questionnaire designed to measure the severity of insomnia based on the diagnostic criteria of the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders.

Sociodemographic variables included age (date of birth), gender, nationality, length of residence in Spain, marital status (single, unmarried partners, married, divorced, widowed), educational level (no studies, primary, high school, university) and employment status (employed, unemployed, retired, housewife and other).

Medical variables included the following:

Comorbidity variables: hypertension, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg; heart failure, which was defined as symptoms of dyspnoea or oedema associated with bilateral rales, elevated venous pressure, or interstitial or alveolar oedema on chest X-ray, and required the addition of diuretics or inotropic medications; myocardial infarction, defined as a history of chest pain/discomfort associated with elevation of ST segment in ECG in two or more contiguous leads and elevation of myocardial enzymes; stroke, defined as a rapidly developing clinical syndrome of focal disturbance of cerebral function that lasted more than 24 hours; peripheral artery disease, defined as a symptomatic and documented obstruction of the distal arteries of the leg; low limb amputations, defined as the complete loss in the transverse anatomical plane of any part of the lower limb; erectile dysfunction, defined as the consistent inability to achieve or maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance; retinopathy, defined as a documented diagnosis by an ophthalmologist of non-proliferative retinopathy, proliferative retinopathy or macular oedema; nephropathy, defined as a history of renal disease due to diabetes mellitus or requiring dialysis; neuropathy, defined as diminished or lack of perception of touch or pain stimuli and loss of joint position sense and vibration sense, and renal failure, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate below 30 mL/1.73 m2. Cardiovascular disease was defined as one or more of the following: myocardial infarction, stroke or peripheral vascular disease.

Other clinical variables: duration of diabetes (years) and family history of diabetes (in the first-degree relatives).

Anthropometric variables: height, weight, body mass index (BMI), hip circumference, waist circumference, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure.

Laboratory results: albuminuria, creatinine, lipid profile, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and glucose.

Personal health habits: (1) Smoking (never, former or current smoker). (2) Physical activity level which was measured using a short questionnaire based on the FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation Report Energy and Protein Requirements (Geneva, 1985) and administered individually at a medical examination. The answers were coded from 1 to 3, with 1 representing inactivity or sedentary activity (remaining seated or at rest most of the time, sleeping, resting, sitting or standing, walking on flat ground, light housework, playing cards, sewing, cooking, studying, driving, typing, office duties, etc.), 2 representing low activity (walking at 5 km/hour, heavy housework (cleaning windows, etc), jobs such as carpenter, construction workers (except hard work), chemical industry, electrical, mechanised agricultural tasks, playing golf, child care, etc), and 3, moderate or vigorous activity (non-mechanised agricultural tasks, mining, forestry, digging, chopping wood, hand mowing, climbing, mountaineering, playing football, tennis, jogging, dancing, skiing, etc). (3) Drinking (0.1 through 4.9, or 5.0 or more g/d of alcohol).

Treatment: statins, β-blockers, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, antiplatelet drugs, antidiabetics, antidepressant drugs and anxiolytics.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and SD; qualitative variables were expressed as frequency distribution. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared using the t test, non-normally distributed variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d for continuous measures and Cramer’s V for categorical variables.

Given the hierarchical structure of our data, we used a logistic regression analysis with two levels: level 1, patients, and level 2, health centres (our sampling unit). However, in the initial step (null model), the variation in the prevalence of depression between centres was not significant (σ2u0=0.02, SE=0.02, p=0.115), with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.007; therefore, we did not consider it necessary to adjust for a hierarchical model.

Explanatory multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to identify variables that were independently associated with depression (prevalent). We report adjusted ORs with their respective 95% CIs. Variables that were statistically significant in the bivariate analysis and those shown to be predictors in previous studies were included in the multivariate analysis. We analysed the possibility of overadjustment, defined when after adjusting on the covariate it altered the adjusted OR of 10%–20% with a concomitant change in the SE higher than 20%.

The annual incidence rate of depression was calculated by the standard method as follows: number of new cases of depression over a period (year 2011)/population at risk of developing the disease at the beginning of the period.

In all cases, the accepted level of significance was 0.05 or less, with a 95% CI. Data were processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS for windows, V.21.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, USA).

Ethical aspects

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

Characteristics of the study population and prevalence of depression

A total of 3443 patients was included in the study at the first recruitment drive (January 2007). Of these 3217 were alive before the start of the survey (January 2013) and 2228 agreed to the interview (participation rate: 69.3%). At the second recruitment, 727 patients agreed to participate (December 2010). Therefore, for the main objective of this study, the sample consisted of 2955 people; 48.1% were women and the mean age was 70.2 years (SD 10.6).

Depression was prevalent in 20.03% (n=592; 95% CI 18.6% to 21.5%). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample, stratified by depression status.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample, with and without depression

| Total (n=2955) |

With depression (n=592) |

Without depression (n=2363) |

P values | Effect size* | |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||

| Gender (female); % (n) | 48.1 (1421) | 67.7 (401) | 43.02 (1020) | <0.001 | 0.197† |

| Age (years); mean (SD) | 70.2 (10.6) | 71.1 (10.3) | 69.9 (10.7) | 0.017 | 0.110‡ |

| Country of origin (foreign-born); % (n) | 2.4 (70) | 2.9 (17) | 2.2 (53) | 0.368 | 0.017† |

| Marital status; % (n) | <0.001 | 0.123† | |||

| Single without partner | 4.6 (136) | 2.7 (16) | 5.1 (120) | ||

| Married or with partner | 70.4 (2077) | 62 (366) | 72.5 (1711) | ||

| Divorced | 4.2 (124) | 5.9 (35) | 3.8 (89) | ||

| Widowed | 20.8 (614) | 29.3 (173) | 18.7 (441) | ||

| Educational level; % (n) | <0.001 | 0.081† | |||

| Not completed | 20.9 (613) | 25.7 (152) | 19.5 (461) | ||

| Primary | 46.7 (1367) | 48.6 (288) | 46.7 (1104) | ||

| Secondary | 19.7 (576) | 16.4 (97) | 20.3 (479) | ||

| University | 12.8 (374) | 9.3 (55) | 13.5 (319) | ||

| Employment status; n (%) | |||||

| Employed | 15.7 (459) | 9.5 (56) | 17 (403) | <0.001 | 0.084† |

| Variables related to diabetes | |||||

| Duration of diabetes (years); mean (SD) | 15.4 (10.2) | 16.5 (10.6) | 15.06 (10) | 0.002 | 0.143‡ |

| Family history of diabetes (yes); % (n) | 61.7 (1813) | 64.5 (382) | 61.3 (1448) | 0.145 | 0.027† |

| Type of diabetes treatment; % (n) | <0.001 | 0.121† | |||

| Only diet | 8.4 (248) | 7.4 (44) | 8.6 (204) | ||

| Oral antidiabetic agents | 53.2 (1572) | 47.3 (280) | 54.7 (1292) | ||

| Insulin | 5.4 (159) | 6.9 (41) | 5 (118) | ||

| Oral antidiabetic agents+insulin | 16.9 (498) | 25.2 (149) | 14.8 (349) | ||

| Not specified | 16.2 (478) | 13.2 (78) | 16.9 (400) | ||

| Lifestyle and self-care | |||||

| Smoking habit; % (n) | <0.001 | 0.127† | |||

| Never smoker | 46 (1360) | 58.6 (347) | 42.9 (1013) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 42.6 (1259) | 32.1 (190) | 45.2 (1069) | ||

| Smoker | 11.4 (336) | 9.3 (55) | 11.9 (281) | ||

| Current regular alcohol use; % (n) | 883 (33.6) | 22 (111) | 36.4 (772) | <0.001 | 0.120† |

| Physical activity; % (n) | <0.001 | 0.117† | |||

| Sedentary | 11.3 (333) | 18.4 (109) | 9.5 (224) | ||

| Low | 81.5 (2408) | 76.5 (453) | 82.7 (1955) | ||

| Moderate-vigorous | 7.2 (214) | 5.1 (30) | 7.8 (184) | ||

| Clinical risk factors | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2); mean (SD) | 31.1 (5.6) | 32.4 (6.4) | 31.2 (5.8) | <0.001 | 0.196‡ |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg); mean (SD) | 131.5 (12.6) | 129.3 (12.6) | 131.9 (11.9) | <0.001 | 0.208‡ |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg); mean (SD) | 73.9 (7.5) | 73.3 (7.6) | 74.2 (7.4) | <0.001 | 0.120‡ |

| Biochemical risk factors | |||||

| HbA1c (%); mean (SD) | 7.1 (1.1) | 7.1 (1.2) | 7.3 (1.5) | 0.703 | 0.110‡ |

| Triglycerides; mean (SD) | 142.4 (87.6) | 148.9 (89.7) | 140.7 (86.9) | 0.070 | 0.092‡ |

| Cholesterol; mean (SD) | 175.7 (33.9) | 181.1 (37.1) | 174.3 (32.9) | <0.001 | 0.194‡ |

| LDL-cholesterol; mean (SD) | 99.2 (27.3) | 101.6 (29.9) | 98.3 (27.1) | 0.064 | 0.115‡ |

| HDL-cholesterol; mean (SD) | 49.5 (13.2) | 50.6 (12.9) | 49.1 (13.3) | 0.032 | 0.114‡ |

| Complications and comorbidities | |||||

| Cardiovascular event (includes non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke and peripheral artery disease); % (n) | 29.7 (1240) | 31.9 (212) | 29.3 (1028) | 0.178 | 0.021† |

| Heart failure; % (n) | 11.5 (480) | 13.7 (91) | 11.1 (389) | 0.053 | 0.030† |

| Lower limb amputation; % (n) | 1.4 (60) | 1.8 (12) | 1.4 (48) | 0.385 | 0.013† |

| Nephropathy; % (n) | 13.5 (400) | 16.2 (96) | 12.9 (304) | 0.033 | 0.039† |

| Neuropathy; % (n) | 10.1 (299) | 16.7 (99) | 8.5 (200) | <0.001 | 0.111† |

| Retinopathy; % (n) | 15 (442) | 15.7 (93) | 14.8 (349) | 0.566 | 0.011† |

| Renal failure; % (n) | 14.3 (424) | 17.6 (104) | 13.5 (320) | 0.012 | 0.046† |

| Psychosocial variables | |||||

| Family history of depression (yes); % (n) | 197 (6.7) | 10.6 (63) | 5.7 (134) | <0.001 | 0.080† |

| Personal history of depression (yes); % (n) | 557 (18.8) | 48.6 (288) | 11.4 (269) | <0.001 | 0.381† |

| Self-reported health status (fair or poor); % (n) | 34.3 (992) | 47 (269) | 31.1 (723) | <0.001 | 0.133† |

| Physical quality of life; mean (SD) | 40.1 (11.4) | 35.3 (12.5) | 41.5 (10.7) | <0.001 | 0.533‡ |

| Mental quality of life; mean (SD) | 47.4 (10.9) | 41.3 (12.5) | 49.1 (9.7) | <0.001 | 0.697‡ |

| Social support (network size); mean (SD) | 10.2 (8.3) | 8.5 (7.3) | 10.6 (8.5) | <0.001 | 0.217‡ |

| Sleep (AIS); mean (SD) | 2.6 (3.7) | 5.3 (5.2) | 2 (2.9) | <0.001 | 0.783‡ |

*0.2 is the recommended minimum effect size

†Cramer’s V

‡Cohen’s d

AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin. Cardiovascular event, includes nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral artery disease.

Compared with patients without depression, people with depression were more likely to be female (p<0.001), older (p=0.017), and widowed or divorced (p<0.001). They also, had a lower educational level (p<0.001), were less frequently classified as employed (p<0.001) and had been taking more intense diabetes treatment for a longer time (p=<0.001). Furthermore, patients with depression had higher BMIs (p<0.001), were lower consumers of alcohol (p<0.001) and had higher rates of never smoking (p<0.001), sedentary lifestyle (p<0.001), neuropathy (P<0.001) and renal failure (p=0.012). Anxiety was recorded in 14.8% of the sample (n=438; 95% CI 13.5 to 16.1). Coexistence of depression and anxiety was recorded in up to 8.6% (n=255) of the patients.

In addition, patients with depression more frequently had previous episodes of depression (p<0.001) and anxiety (p<0.001), and fair or poor self-reported health status (p<0.001) than patients without these disorders. No significant differences were observed between patients with depression and psychologically healthy subjects in the following: family history of diabetes, level of HbA1c, triglycerides values, nephropathy and retinopathy.

Factors associated with prevalent depression

Table 2 shows the variables associated with depression after adjusting fully for potential confounding factors. The variable most strongly associated with depression was previous personal history of depression (OR 6.482; 95% CI 5.138 to 8.178; p≤0.001), followed by neuropathy (OR 1.951; 95% CI 1.423 to 2.674; p≤0.001), treatment with oral antidiabetic agents plus insulin (OR 1.802; 95% CI 1.364 to 2.380; p≤0.001), fair or poor self-reported health status (OR 1.509; 95% CI 1.209 to 1.882; p≤0.001), mental health score (SF-12) below the mean (OR 1.423; 95% CI 1.054 to 1.921; p=0.021), ≤ female gender (OR 1.333; 95% CI 1.009 to 1.761; p=0.043) and blood cholesterol level (OR 1.005; 95% CI 1.002 to 1.009; p=0.002).

Table 2.

Factors associated with prevalence of depression (logistic regression analysis) (Hosmer-Lemeshow=5.132; df=5; p=0.743)

| OR | 95% CI | P values | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.333 | 1.009 to 1.761 | 0.043 |

| Age | |||

| <65 years | 1 | ||

| ≥65 years | 0.858 | 0.626 to 1.175 | 0.339 |

| Duration of T2DM (years) (per unit of increment) | 1.006 | 0.995 to 1.016 | 0.303 |

| Educational level | |||

| University | 1 | ||

| Secondary | 0.980 | 0.644 to 1.493 | 0.926 |

| Primary | 1.060 | 0.729 to 1.543 | 0.759 |

| Not completed | 1.118 | 0.735 to 1.699 | 0.602 |

| Country of origin | |||

| Spain | 1 | ||

| Other | 1.433 | 0.738 to 2.784 | 0.288 |

| Employment status | |||

| Not working | 1 | ||

| Working | 0.595 | 0.397 to 0.894 | 0.012 |

| Smoking | |||

| Never smoker | 1 | ||

| Former smoker | 0.854 | 0.652 to 1.119 | 0.252 |

| Current smoker | 0.874 | 0.585 to 1.306 | 0.510 |

| Family history of diabetes mellitus | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.109 | 0.888 to 1.385 | 0.362 |

| Current alcohol use | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.726 | 0.552 to 0.954 | 0.022 |

| Physical activity | |||

| Sedentary | 1 | ||

| Low | 0.552 | 0.408 to 0.746 | <0.001 |

| Moderate-vigorous | 0.636 | 0.377 to 1.074 | 0.091 |

| Diabetes treatment | |||

| Oral antidiabetic agents | 1 | ||

| Oral antidiabetic agents+insulin | 1.802 | 1.364 to 2.380 | <0.001 |

| Insulin | 1.476 | 0.938 to 2.323 | 0.092 |

| Diet | 0.932 | 0.623 to 1.394 | 0.731 |

| Unknown | 0.771 | 0.560 to 1.061 | 0.110 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (per unit of increment) | 1.012 | 0.992 to 1.032 | 0.249 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) (per unit of increment) | 0.982 | 0.971 to 0.992 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) (per unit of increment) | 0.992 | 0.974 to 1.009 | 0.358 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) (per unit of increment) | 1.005 | 1.002 to 1.009 | 0.002 |

| Neuropathy | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.951 | 1.423 to 2.674 | <0.001 |

| Nephropathy | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.077 | 0.782 to 1.483 | 0.649 |

| Retinopathy | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.784 | 0.578 to 1.065 | 0.119 |

| Renal failure | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.220 | 0.892 to 1.670 | 0.214 |

| Self-reported health status | |||

| Excellent-very good-good | 1 | ||

| Fair-poor | 1.509 | 1.209 to 1.882 | <0.001 |

| Family history of depression | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.419 | 0.975 to 2.066 | 0.067 |

| Personal history of depression | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 6.482 | 5.138 to 8.178 | <0.001 |

| Social support (network size) (per unit of increment) | 0.978 | 0.962 to 0.993 | 0.005 |

| Physical Health Score (SF-12) | |||

| Score ≥mean | 1 | ||

| Score <mean | 1.243 | 0.910 to 1.699 | 0.171 |

| Mental Health Score (SF-12) | |||

| Score ≥mean | 1 | ||

| Score <mean | 1.423 | 1.054 to 1.921 | 0.021 |

| History of cancer | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.961 | 0.716 to 1.290 | 0.792 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.156 | 0.901 to 1.482 | 0.255 |

| Heart failure | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.297 | 0.910 to 1.849 | 0.150 |

| Lower limb amputation | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.765 | 0.798 to 3.904 | 0.160 |

BP, blood pressure, BMI, body mass index; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

On the other hand, the variables inversely associated with depression were: being employed (OR 0.595; 95% CI 0.397 to 0.894; p=0.012), low physical activity (OR 0.552; 95% CI 0.408 to 0.746; p≤0.001), systolic blood pressure (OR 0.982; 95% CI 0.971 to 0.992; p=0.001), current alcohol use (OR 0.726; 95% CI 0.552 to 0.954) and social support (network size) (OR 0.978; 95% CI 0.962 to 0.993; p=0.005).

Incidence of depression and predictive factors

During a median 12-month follow-up, 28 patients without depression at baseline, developed an incident episode of depression, that is an annual incidence of 1.2% (95% CI 1.11% to 2.81%). There were differences by gender: 0.6% (95% CI 0.13% to 1.07%) in men and 2% (95% CI 1.11% to 2.81%) in women (p=0.002). Female gender was the variable most strongly associated with incidence of depression (OR 2.620; 95% CI 1.129 to 6.083; p=0.025). Other variables inversely associated with incidence of depression were: low physical activity (OR 0.334; 95% CI 0.136 to 0.818; p=0.018), diastolic blood pressure (per each unit of increment) (OR 0.937; 95% CI 0.887 to 0.988; p=0.017) and social support (network size) (OR 0.875; 95% CI 0.797 to 0.962; p=0.006).

Of the 592 patients initially identified as depressed, 394 (66.66%) had no symptoms or signs of depression after 1 year of follow-up and 198 (33.33%) persisted with symptoms.

Discussion

The association between diabetes and depression has been well known for at least three decades.4 The prevalence of depression in people with T2DM varies widely owing to circumstances such as differences in the methods used to assess depression (clinical interviews, questionnaires, self-report scales and medical records), sample origin (clinical or outpatient screening), ethnic subgroups, gender composition and age intervals. Two meta-analyses reported an overall prevalence of depression ranging from 17.6% to 27%.4 We analysed the prevalence of depression in a cohort of patients with T2DM from the city of Madrid based on a clinical interview completed with prescribing and clinical data from CCR. Depression was prevalent in 20.03% (n=592; 95% CI 18.6 to 21.5) of our sample, a finding that is lower than the 27.2% reported in primary-care settings and a hospital endocrinology department in Mallorca (Spain) using the Beck Depression Inventory as the screening tool.12 These findings are worrying, given the adverse impact of depression on the natural history of T2DM, which takes the form of poor metabolic control,27 non-adherence to treatment28 29 and increased risk of vascular complications.8

Poor social support and negative life events (ie, adverse socioeconomic circumstances, death of relatives) have been associated with depression in people with T2DM.30 These two factors are more frequent in women,31 32 thus explaining the predominance of depression among women, as reported by the vast majority of studies.33 34 However, not all the studies have confirmed this hypothesis.35

After adjusting for gender and other known risk factors, our findings show that the association with depression was reduced by 2.2% per unit of increment of network size. Similarly, the association with depression could be reduced by physical activity, as we found in patients with low physical activity compared with a sedentary lifestyle (OR 0.552; 95% CI 0.408 to 0.746; p≤0.001). However, we did not demonstrate a similar benefit in those who undertake moderate or vigorous physical activity. This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that very few had a high level of activity.

General practitioners should be encouraged to implement strategies designed to reduce the risk of depression in patients with T2DM, especially in those at high risk of depression owing to exposure to chronic psychosocial stressors.29

We found an inverse association between low physical activity and social support and depression. While this association does not necessarily imply a causal relationship, it might encourage the implementation of physical activity programmes and the creation of support groups focused on psychological well-being and detection of depressive symptoms. Some of these suggestions have proven to be effective and feasible in older populations.36

On the other hand, it is necessary to bear in mind that treatment of depression can be a prerequisite for good diabetes control because people with diabetes might follow their treatment plan more easily if their mood is improved first.37

Other predictive factors of depression such as a previous depressive episode or family history of depression are not modifiable factors for reducing the risk of developing depression. However, health professionals must be alert to the presence of early symptoms of depression in order to treat this condition promptly. Indeed, routine screening for psychosocial problems such as depression is supported in well-conducted cohort studies.38 In this sense, screening for depression with questionnaires is insufficiently specific and needs to be complemented by a formal clinical assessment to confirm the diagnosis.37

Being in employment was inversely associated with depression (OR 0.595; p=0.012), as shown elsewhere.39 This aspect suggests that going to work might have a protective role against depression owing to the social support received from co-workers.

Of the classic complications of diabetes, neuropathy was the only one significantly associated with depression (OR 1.951; p≤0.001). Nephropathy, renal failure, heart failure, CVD and lower limb amputation tended to have a positive association with depression. However, other studies have shown a significant and consistent association between complications of diabetes and depressive symptoms.8 As it was logical to suppose, subjects with depression had lower values in the mental health component score obtained from the SF-12, as reported elsewhere.40

Consistent with other studies,41 42 we found that participants with depression self-rated their health status significantly lower than those without depression. Given the known relationship between fair/poor perceived health status and mortality,43 especially in patients with chronic diseases,44 it would be advisable for patients with poor self-rated health to be enrolled in a health coaching programme similar to that used in the Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia.45 In this programme, patients with diabetes who had the lowest self-reported health status at baseline improved their rating in the first question of the Short-Form 36 Quality of Life Instrument (SF-1) from 4.4 to 3.7 (p≤0.001), and improved their knowledge of diabetes. Their distress levels decreased significantly with respect to baseline values.

Medications for lowering blood sugar (insulin plus oral antidiabetic agents) were significantly associated with depression (OR 1.802; p≤0.001). Prior studies have highlighted the same phenomenon: glucose-lowering therapies that include insulin are strongly associated with depression.46 Two different factors could explain this association: first, the implementation of insulin therapy requires painful injections and frequent glucose measurements, thus increasing stress and favouring the onset of a depressive episode in old age;47 second, since insulin is usually necessary for situations of poor glycaemic control, it could be that non-optimal control of diabetes leads to worsening of mood, greater stress and less life satisfaction.

As for the incidence of depression after 1 year of follow-up, the present study reveals a value of 1.20% which is similar to that reported in the ZARADEMP Spanish Study,48 but lower than reported in other countries.5 49–51 A possible explanation for this result could be that, compared with other European countries, the greater number of hours of sunlight in Spain protect against depression.50 In a meta-analysis51 that evaluated 16 studies to analyse the relationship between diabetes and depression, the cumulative incidence of depression among people with diabetes ranged from 11.9%, after 2 years of follow-up,52 to 23.5%, after 5.9 years of follow-up.53 The conclusion of the meta-analysis54 is that there is evidence to support the hypothesis that diabetes is a ’depressogenic' condition. This affirmation implies a real public health problem that may be resolved only by a specific prevention strategy.

Our findings have some limitations. First, the external validity of these results is limited because the study population may not be representative of the actual population of patients with diabetes. Second, the time between both telephone interviews for depression screening was too short (12 months), making it difficult to compare cumulative incidence rates with most studies. Third, the prescription of antidepressants takes place in diseases other than depression (ie, sleeping disorders, migraine, neuropathic pain, obsessive-compulsive disorders, anxiety/panic disorder), and the use of a combined variable for the diagnosis of depression includes the prescription of antidepressant medication and could have therefore overestimated its prevalence. Fourth, in order to compare multivariate models from different studies, it is possible that we just performed an unnecessary adjustment of variables. But, fortunately, there was no significant evidence for overadjustment (changes >20% between crude and adjusted SE, data not shown).

Strengths of this study include: the prospective design, which ensured that measurement of risk factors preceded the development of depression; and the assessment of information on potentially confounding variables, which reduces the potential selection and confusion biases. We also used an assessment of depression based on MINI V.5.0, completed with having been diagnosed with depression, treatment with antidepressant medications or any of these conditions. Therefore, self-reported diagnosis was avoided.

Conclusions

Depression is very prevalent among patients with T2DM and it is associated with several key diabetes-related outcomes. Our results suggest that previous mental status, self-reported health status, and some diabetes-related complications are associated with differences in the degree of depression. We also found sex-related differences with respect to the prevalence of depression. Our study shows that the risk of depression could be reduced by physical activity and social support. These findings should alert practitioners to the importance of detection of depression in patients with T2DM, and to the need to reduce the risk of depression with prevention programmes focused on improving the physical activity of the patients and the creation of support groups. Our findings also suggest that the annual incidence rate of depression is low and that a high proportion of patients with T2DM who experience depression achieved full remission after 1 year of follow-up.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all health professionals of the Primary Health Care of Madrid who have made its development possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: CDB-L and MAS-F designed the study and obtained funding. JC-V, PG-C, JCA-H, RMC-M and DB-V selected the patient sample by the participating general practitioner, collected data and combined the data collection strategies in a single database. FJSA-R, CDB-L, YR-F, PG-C and MAS-F analysed the data. PG-C, MAS-F and JMdM-Y wrote the initial draft of the paper. RJ-G, AL-A, CDB-L and ECdSP were involved in further drafting of the paper. All authors interpreted the data, revised the paper critically for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the submitted version.

Funding: This study forms part of research funded by FIS (Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias—Health Research Fund, Instituto de Salud Carlos III) grants no.: PI10/02796, PI12/01806 and PI15/00259 and co-financed by the European Union through the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER, “Una manera de hacer Europa”). Also, this article has been supported by the Foundation for Biomedical Research and Innovation of Primary Care FIIBAP through the call for aid for publications 2017.(https://saluda.salud.madrid.org/atencionprimaria/investigacion/Paginas/fiibap.aspx).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Review Board of the Ramón y Cajal Hospital (Madrid).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available

Collaborators: The members of the MADIABETES Group are as follows : AM Sobrado-de Vicente-Tutor; Mar Sanz-Pascual; M Arnalte-Barrera; S Pulido-Fernández; EM Donaire-Jiménez; C Montero-Lizana; M Domínguez-Paniagua; P Serrano-Simarro; R Echegoyen-de Nicolás; P Gil-Díaz; I Cerrada-Somolinos; R Martín-Cano; A Cava-Rosado; T Mesonero-Grandes; E Gómez-Navarro; A Maestro-Martín; A Muñoz-Cildoz; ME Calonge-García; M Martín-Bun; P Carreño-Freire; J Fernández-García; A Morán-Escudero; J Martínez-Irazusta; E Calvo-García; AM Alayeto-Sánchez; C Reyes-Madridejos; MJ Bedoya-Frutos; B López-Sabater; J Innerarity-Martínez; A Rosillo-González; AI Menéndez-Fernández; F Mata-Benjumea; P Vich-Pérez; C Martín-Madrazo; MJ Gomara-Martínez; C Bello-González; A Pinilla-Carrasco; M Camarero-Shelly; A Cano-Espin; J Castro Martin; B de Llama-Arauz; A de Miguel-Ballano; MA García-Alonso; JN García-Pascual; MI González-García; C López-Rodríguez; M Miguel-Garzón; MC Montero-García; S Muñoz-Quiros-Aliaga; S Núñez-Palomo; O Olmos-Carrasco; N Pertierra-Galindo; G Reviriego-Jaén; P Rius-Fortea; G Rodríguez-Castro; JM San Vicente-Rodríguez; ME Serrano-Serrano; MM Zamora-Gómez; and MP Zazo-Lázaro.

Contributor Information

The MADIABETES Research Group:

Sobrado-de AM, Mar Sanz-Pascual, M Arnalte-Barrera, S Pulido-Fernández, EM Donaire-Jiménez, C Montero-Lizana, M Domínguez-Paniagua, P Serrano-Simarro, R Echegoyen-de Nicolás, P Gil-Díaz, I Cerrada-Somolinos, R Martín-Cano, A Cava-Rosado, T Mesonero-Grandes, E Gómez-Navarro, A Maestro-Martín, A Muñoz-Cildoz, Me Calonge-García, M Martín-bun, P Carreño-Freire, J Fernández-García, A Morán-Escudero, J Martínez-Irazusta, E Calvo-García, AM Alayeto-Sánchez, C Reyes-Madridejos, Mj Bedoya-Frutos, B López-Sabater, J Innerarity-Martínez, A Rosillo-González, Ai Menéndez-Fernández, F Mata-Benjumea, P Vich-Pérez, C Martín-Madrazo, Mj Gomara-Martínez, C Bello-González, A Pinilla-Carrasco, M Camarero-Shelly, A Cano-Espin, J Castro Martin, B De Llama-Arauz, A De Miguel-Ballano, Ma García-Alonso, JN García-Pascual, MI González-García, C López-Rodríguez, M Miguel-Garzón, MC Montero-García, S Muñoz-Quiros-Aliaga, S Núñez-Palomo, O Olmos-Carrasco, N Pertierra-Galindo, G Reviriego-Jaén, P Rius-Fortea, G Rodríguez-Castro, Jm San Vicente-Rodríguez, ME Serrano-Serrano, MM Zamora-Gómez, and MP Zazo-Lázaro

References

- 1. Anon. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4·4 million participants. The Lancet 2016;387:1513–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00618-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soriguer F, Goday A, Bosch-Comas A, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose regulation in Spain: the Di@bet.es Study. Diabetologia 2012;55:88–93. 10.1007/s00125-011-2336-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knol MJ, Twisk JW, Beekman AT, et al. Depression as a risk factor for the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus. A meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2006;49:837–45. 10.1007/s00125-006-0159-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1069–78. 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA 2008;299:2751–9. 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lunghi C, Moisan J, Grégoire JP, et al. Incidence of depression and associated factors in patients with type 2 diabetes in Quebec, Canada: a population-based cohort study. Medicine 2016;95:e3514 10.1097/MD.0000000000003514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Dooren FE, Nefs G, Schram MT, et al. Depression and risk of mortality in people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e57058 10.1371/journal.pone.0057058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, et al. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2001;63:619–30. 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications 2005;19:113–22. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2004.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schram MT, Baan CA, Pouwer F. Depression and quality of life in patients with diabetes: a systematic review from the European depression in diabetes (EDID) research consortium. Curr Diabetes Rev 2009;5:112–9. 10.2174/157339909788166828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jimenez-Garcıa R, Martinez Huedo MA, Hernandez-Barrera V, et al. Psychological distress and mental disorders among Spanish diabetic adults: a case-control study. Prim Care Diabetes 2012;6:149–56. 10.1016/j.pcd.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nicolau J, Simó R, Sanchís P, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlators of undiagnosed significant depressive symptoms among individuals with type 2 diabetes in a mediterranean population. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes Off J Ger Soc Endocrinol Ger Diabetes Assoc 2016;124:630–6. 10.1055/s-0042-109606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lopez-de-Andrés A, Jiménez-Trujillo MI, Hernández-Barrera V, et al. Trends in the prevalence of depression in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes in Spain: analysis of hospital discharge data from 2001 to 2011. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117346 10.1371/journal.pone.0117346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alonso-Morán E, Satylganova A, Orueta JF, et al. Prevalence of depression in adults with type 2 diabetes in the Basque Country: relationship with glycaemic control and health care costs. BMC Public Health 2014;14:769 10.1186/1471-2458-14-769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esteban y Peña MM, Hernandez Barrera V, Fernández Cordero X, et al. Self-perception of health status, mental health and quality of life among adults with diabetes residing in a metropolitan area. Diabetes Metab 2010;36:305–11. 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hervás A, Zabaleta A, De Miguel G, et al. [Health related quality of life in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2]. An Sist Sanit Navar 2007;30:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salinero-Fort MÁ, San Andrés-Rebollo FJ, de Burgos-Lunar C, et al. Four-year incidence of diabetic retinopathy in a Spanish cohort: the MADIABETES study. PLoS One 2013;8:e76417 10.1371/journal.pone.0076417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Burgos-Lunar C, Gómez-Campelo P, Cárdenas-Valladolid J, et al. Effect of depression on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in type 2 diabetes mellitus after 3 years follow up. The DIADEMA study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:95 10.1186/1471-244X-12-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Organization of National Colleges, Academies, and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians. ICPC-2-R: international classification of primary care. Rev. 193 2nd edn Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 3 2nd edn Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pan A, Lucas M, Sun Q, et al. Increased mortality risk in women with depression and diabetes mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:42 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59:22–33. quiz 34-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferrando L, Bobes J, Gibert J, et al. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Versión en español 5.0.0. 2000: Madrid. 2000.

- 24. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–14. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summaries: a user’s manual. Boston: New England Medical Centre, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gómez-Benito J, Ruiz C, Guilera G. A Spanish version of the athens insomnia scale. Qual Life Res 2011;20:931–7. 10.1007/s11136-010-9827-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Egede LE, Ellis C. Diabetes and depression: global perspectives. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:302–12. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin EH, Katon W, Rutter C, et al. Effects of enhanced depression treatment on diabetes self-care. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:46–53. 10.1370/afm.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin EH, Rutter CM, Katon W, et al. Depression and advanced complications of diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 2010;33:264–9. 10.2337/dc09-1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Habtewold TD, Alemu SM, Haile YG. Sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors associated with depression among type 2 diabetic outpatients in Black Lion General Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:103 10.1186/s12888-016-0809-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kraaij V, Arensman E, Spinhoven P. Negative life events and depression in elderly persons: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57:P87–94. 10.1093/geronb/57.1.P87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krag MØ, Hasselbalch L, Siersma V, et al. The impact of gender on the long-term morbidity and mortality of patients with type 2 diabetes receiving structured personal care: a 13 year follow-up study. Diabetologia 2016;59:275–85. 10.1007/s00125-015-3804-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cols-Sagarra C, López-Simarro F, Alonso-Fernández M, et al. Prevalence of depression in patients with type 2 diabetes attended in primary care in Spain. Prim Care Diabetes 2016;10:369–75. 10.1016/j.pcd.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naranjo DM, Fisher L, Areán PA, et al. Patients with type 2 diabetes at risk for major depressive disorder over time. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:115–20. 10.1370/afm.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dalgard OS, Dowrick C, Lehtinen V, et al. Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression: a multinational community survey with data from the ODIN study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:444–51. 10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cole MG. Brief interventions to prevent depression in older subjects: a systematic review of feasibility and effectiveness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;16:435–43. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318162f174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petrak F, Baumeister H, Skinner TC, et al. Depression and diabetes: treatment and health-care delivery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:472–85. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2016 Abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes 2016;34:3–21. 10.2337/diaclin.34.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mocan AS, Iancu SS, Duma L, et al. Depression in romanian patients with type 2 diabetes: prevalence and risk factors. Clujul Med 2016;89:371–7. doi:10.15386/cjmed-641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yoshida S, Hirai M, Suzuki S, et al. Neuropathy is associated with depression independently of health-related quality of life in Japanese patients with diabetes. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;63:65–72. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01889.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sundaram M, Kavookjian J, Patrick JH, et al. Quality of life, health status and clinical outcomes in Type 2 diabetes patients. Qual Life Res 2007;16:165–77. 10.1007/s11136-006-9105-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McCollum M, Ellis SL, Regensteiner JG, et al. Minor depression and health status among US adults with diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care 2007;13:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mossey JM, Shapiro E. Self-rated health: a predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am J Public Health 1982;72:800–8. 10.2105/AJPH.72.8.800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37. 10.2307/2955359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Delaney G, Newlyn N, Pamplona E, et al. Identification of patients with diabetes who benefit most from a health coaching program in chronic disease management, Sydney, Australia, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2017;14:E21 10.5888/pcd14.160504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Otieno F, Kanu J, Karari E, et al. adequacy of metabolic control, and their relationship with comorbid depression in outpatients with type 2 diabetes in a tertiary hospital in Kenya. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther 2017;10:141–9. 10.2147/DMSO.S124473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Brilman EI, Ormel J. Life events, difficulties and onset of depressive episodes in later life. Psychol Med 2001;31:859–69. 10.1017/S0033291701004019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. de Jonge P, Roy JF, Saz P, et al. Prevalent and incident depression in community-dwelling elderly persons with diabetes mellitus: results from the ZARADEMP project. Diabetologia 2006;49:2627–33. 10.1007/s00125-006-0442-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knol MJ, Heerdink ER, Egberts AC, et al. Depressive symptoms in subjects with diagnosed and undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. Psychosom Med 2007;69:300–5. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31805f48b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nouwen A, Winkley K, Twisk J, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for the onset of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2010;53:2480–6. 10.1007/s00125-010-1874-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lambert GW, Reid C, Kaye DM, et al. Effect of sunlight and season on serotonin turnover in the brain. Lancet 2002;360:1840–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11737-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hasan SS, Mamun AA, Clavarino AM, et al. Incidence and risk of depression associated with diabetes in adults: evidence from longitudinal studies. Community Ment Health J 2015;51:204–10. 10.1007/s10597-014-9744-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, et al. Vascular risk factors and incident late-life depression in a Korean population. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:26–30. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.015032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maraldi C, Volpato S, Penninx BW, et al. Diabetes mellitus, glycemic control, and incident depressive symptoms among 70- to 79-year-old persons: the health, aging, and body composition study. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1137–44. 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.