Abstract

Objectives

Screening for symptoms of postintensive care syndrome is based on a long list of questionnaires, filled out by the intensive care unit (ICU) survivor and manually reviewed by the health professional. This is an inefficient and time-consuming process. The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of a web-based triage tool and to compare the outcomes from web-based questionnaires to those from paper-based questionnaires.

Design

A mixed-methods study.

Setting

Nine Dutch ICU follow-up clinics.

Participants

221 ICU survivors and 14 health professionals.

Interventions

A web-based triage tool was implemented by nine ICU follow-up clinics. End users, that is, health professionals were interviewed in order to evaluate the feasibility of the triage tool. ICU survivors were invited to fill out web-based questionnaires 3 months after hospital discharge.

Primary outcomes

Outcomes of the questionnaires were merged with clinical data from a national quality registry to assess the differences in outcomes between paper-based and web-based questionnaires.

Results

221 ICU survivors received an invitation to fill out questionnaires, 93 (42.1%) survivors did not respond to the invitation. Respondents to the web-based questionnaires (n=54) were significantly younger and had a significantly longer ICU stay than those who preferred the paper-based questionnaires (n=74). The prevalence of mental, physical and nutritional problems was high, although comparable between the groups. Health professionals’ interviews revealed that the software was complex to use (n=8) and although emailing survivors is very convenient, not all survivors have an email address (n=7).

Conclusions

Web-based screening software has major benefits compared with paper-based screening. However, implementation has shown to be rather difficult and there are important barriers to consider. Although different in age, the health status is comparable between the users of the web-based questionnaire and paper-based questionnaire.

Keywords: health informatics, information management, world wide web technology, organisational development

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study is that we implemented the web-based triage tool in a clinical care setting instead of a clinical trial setting.

Outcomes and characteristics of patients which preferred the web-based questionnaires were compared with the outcomes and characteristics of patients which preferred the paper-based questionnaires.

By using mixed methods, we were able to verify the statements of health professionals with the clinical data and questionnaire outcomes.

Introduction

Intensive care unit (ICU) survivors frequently suffer long-term and severe complaints after ICU discharge1 2 and a single term is used to identify the presence of one or more impairments after critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome (PICS).3

Because of the complexity and magnitude of the complaints, multidisciplinary care after ICU discharge is required.4 ICU follow-up care aims to detect PICS in an early stage and the ICU survivors will be referred to the appropriate health professional(s) during consultation. In some ICU guidelines, it is recommended to have an ICU follow-up clinic.5

Generally, screening for symptoms of PICS is based on a long list of paper-based questionnaires, filled out manually by the survivor and reviewed by the health professional before or during consultation. This is an inefficient and time-consuming process. Moreover, there is a high rate of non-responders due to the age and medical conditions of survivors and because survivors cannot always be traced on their home address.6 7

We created a web-based triage tool to collect patient-reported screening data. The tool supports automatic processing of the data before presenting it to the health professional. Web-based screening has major benefits compared with paper-based screening, for example, more complete data, less entry errors and easy storage of data,8 leading to enhanced integrity and accuracy of outcome data.9 In previous literature, the benefits of web-based screening software have been pointed out in clinical trial settings.10 However, research on the implementation of software in clinical care and the use of web-based screening in ICU survivors and ICU personnel is scarce.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of our web-based triage tool in the ICU follow-up clinic and to assess the outcomes gained by web-based questionnaires compared with those from conventional paper-based questionnaires.

Materials and methods

Setting

Based on the recommendations of Van der Schaaf et al,11 (box 1), a new web-based triage tool was created and tested during a pilot study. The tool supports automatic collection and processing of data for ICU follow-up care. The study was conducted between 1 June 2014 and 30 June 2015. All ICUs participating in the Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) registry that had an ICU follow-up clinic were invited to participate in this pilot study. The NICE registry is a quality registry which contains demographic data, physiological data and clinical data for all ICU patients in the Netherlands.12 13 We aimed to include 10 ICU’s in this pilot study.

Box 1. Recommendations for eligibility of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors for ICU follow-up clinics11 .

Invite all survivors who received >48 hours mechanical ventilation.

Invite the partners of survivors.

Plan the first visit to the ICU follow-up clinic 12 weeks after hospital discharge with the possibility for a follow-up at indication.

Screen survivors with respect to their needs and ICU-related sequelae.

Use electronic patient-reported screening instruments to identify survivors in the need for ICU follow-up care.

Have an ICU nurse, whether or not with an intensivist, carrying out the ICU follow-up clinic.

Involve a physiotherapist to perform a comprehensive physical screening.

Integrate follow-up care data into a national quality registry for ICU to monitor and improve quality of life and functional status of survivors.

Web-based triage tool

The triage tool includes a module for health professionals to be used in the follow-up clinic and a web-based questionnaire module for ICU survivors.

During the development of the triage tool, both modules were tested for usability. The module for health professionals was evaluated with four health professionals by means of semistructured interviews.14 The usability of the web-based questionnaire module was evaluated with four ICU survivors using the think aloud method.14 15 Outcomes of the semistructured interviews and the think aloud sessions resulted in minor adjustments of the triage tool prior to implementation of the triage tool in this pilot study.14

The triage tool automatically extracted data of eligible survivors from the hospital information system (HIS). Nine weeks after hospital discharge, the health professionals received a prompt to send the survivor an invitation by email to fill out a set of online questionnaires and to invite the survivor to visit the ICU follow-up clinic 3 months after hospital discharge. If there was no response from the survivor within the next week, the health professional received a prompt to call the survivor. During this phone call, the health professional would ask for the reason of the non-response and explain the importance of screening for PICS and a visit to the ICU follow-up clinic. If survivors stated that they were unable to fill out the online questionnaires, paper-based questionnaires were issued. The paper-based questionnaires were entered in the system manually by the health professional or the secretary.

The pilot study included the questionnaires described in table 1. Besides these validated questionnaires, work and income-related questions, common problems after ICU admission and visits to health professionals after ICU admission were queried (online supplementary appendix 1).

Table 1.

Validated questionnaires used during this study

| Name | Description | Cut-off point |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale27 | A 14-item screening tool consisting of two subscales which evaluate symptoms of depression (seven items) and symptoms of anxiety (seven items). | Scores of ≥8 to identify patients prone to develop depression or anxiety. |

| Short From 3628 | A 36-item screening tool comprising two components; a physical and a mental component score. Component scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health status.29 | Scores of <40 to identify a decreased physical or mental health. |

| Trauma Screening Questionnaire 30 | A 10-item screening tool used to identify post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). | Scores of ≥6 to identify possible PTSD. |

| Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool31 | A 3-item screening tool to obtain the risk of malnutrition. | Scores ≥1 to identify patients with a risk of malnutrition. |

bmjopen-2017-021249supp001.pdf (93.8KB, pdf)

The results of the questionnaires were automatically processed by the triage tool and compared with the cut-off points. During the follow-up consultation, the health professional and the survivor discussed the outcomes of the questionnaires and the survivor was referred to a specialist if necessary. This was similar to the process before the implementation of the triage tool except for the fact that the outcomes of the questionnaires were calculated and present before the start of the consultation.

Health professionals were trained to use the software before the start of the study. The 3-hour training was given by the developers of the tool and a researcher (IvB or FB-R). During the pilot study, the health professionals were contacted regularly and offered assistance when necessary.

Evaluation of the feasibility of the triage tool

After finishing the pilot study, semistructured interviews were conducted with health professionals who used the tool, to gain insight in the feasibility of the triage tool. The semistructured interviews were hold from July 2015 until September 2015 and conducted by one researcher (IvB). All health professionals were interviewed in their own working environment and an informed consent was verbally issued and recorded before the interview started.

All interviews were recorded digitally and transcribed verbatim. The thematic content analysis method was used to analyse the qualitative data.16 All interviews were coded individually by two researches (IvB and FB-R). Both researchers extracted the statements from the transcripts and grouped the statements by themes. The themes and statements were discussed until 100% agreement was achieved on the coding.

The statements of the health professionals were compared with the characteristics of the survivors and the outcomes of the questionnaires in order to relate the qualitative data to the quantitative data.

Finally, the health professionals were requested to fill out the System Usability Scale (SUS).17 The SUS is a tool to evaluate software tools. Scores range from 0 to 100 and a SUS score above 68 is indicating an above average usability.17

Questionnaire outcomes of the ICU survivors

The outcomes of the questionnaires were used to evaluate the type and severity of symptoms of PICS present in survivors. The anonymised data of the questionnaires were linked with clinical data from the NICE registry to gain insight in the demographics and clinical differences between survivors who filled out the web-based questionnaires compared with those who filled out the paper-based questionnaires. Data linking was based on a unique identifying number available in both databases.

Categorical data were presented as numbers and percentages, continuous data as medians and IQR. Differences between the web-based questionnaire group and the paper-based questionnaire group for non-normally distributed data were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences between the two groups for normally distributed data were calculated using the t-test. For categorical data, the χ2 test was used to assess the differences between the study groups. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.24.18

Patient and public involvement

No patients were directly involved in the development of the research question, design of the study or interpretation of the results. However, the usability of the web-based questionnaire module was evaluated with ICU survivors. Outcomes of the evaluation resulted in minor adjustments of the module prior to the implementation of the triage tool in this pilot study.

Results

Of the 23 Dutch ICUs with an ICU follow-up clinic, nine ICUs (39.1%) participated in the pilot study. One ICU withdrew due to reorganisation 8 months after the start of the study. Of the eight participating ICUs, one (12.5%) was located in a university hospital, one (12.5%) in a teaching hospital and six (75.0%) in community hospitals.

Evaluation of the feasibility of the triage tool

During this pilot study, 531 survivors were eligible for follow-up care and were extracted from the HIS. Before sending out the invitations, the health professional would check if the survivor was still alive and 42 (7.9%) survivors were reported as ‘deceased after hospital discharge’. Of the remaining survivors, 221 (45.2%) received an invitation to fill out the questionnaires and to attend follow-up care. Other reasons for not inviting the survivor, besides death, were not collected. There were no significant differences in characteristics between survivors who were invited or not.

Ninety-three (42.1%) survivors did not respond to the invitation. Of the non-responders, 28 (30.1%) were phoned by the health professional to ask for the reason for non-response; three (10.7%) could not be reached on their phone number, 8 (28.6%) said they were well and did not need follow-up care, three (10.7%) said they were unable to fill out questionnaires and to attend follow-up care due to their poor health status, two (7.1%) had no recollection of the ICU admission, six (21.4%) were already involved in a rehabilitation programme, one (3.6%) had no computer and five (17.9%) gave other reasons. It is unknown whether the other 65 non-responders were not contacted or that the phone calls were not registered. There were no significant differences in characteristics between non-responders and responders.

Fourteen health professionals worked with the system and were interviewed; five intensivists, six ICU nurses, one physical therapist and two medical secretaries. The duration of the interviews ranged from 21 to 39 min. Ten health professionals filled out the SUS with an average score of 56.

Table 2 shows the main barriers to using the tool for survivors, according to the health professionals. The email addresses of survivors or family members were not always routinely collected before the start of the study. During the study, this was implemented in the regular workflow in the HIS.

Table 2.

Themes exemplifying the statements of the 14 health professionals

| Themes | Statements |

| Personal themes | Emailing the patient is very convenient, especially during night shifts (n=7). |

| I did not think about emailing the patient, I like to call patients (n=2). | |

| Software-related themes | The software was complex (n=8). |

| Patients’ email addresses were not available in the HIS at the start of the pilot, calling the patient to collect the email address was very time consuming (n=8). | |

| Since we used so little, I forgot how to send an email with it (n=5). | |

| Patient-related themes | Patients did not have an email address, even not the patients of 40–50 years old (n=10). |

| Patients are not ready to use the web-based questionnaires, in 10 years this will be different (n=10). | |

| Some patients are not interested in follow-up care, sometimes they are too sick and sometimes they already have support (n=10). | |

| Organisation-related themes | There are no resources available for follow-up care, we arranged it in our own time (n=4). |

| A follow-up consultation is not part of the ‘routine care process’, patients perceive it as optional and might not come (n = 4). |

Health professionals were surprised to find out that a large part of survivors mentioned not to have an email address, even the ‘younger’ survivors of 40–50 years old. Over 70% of the health professionals said that the ICU population in general is older, and that survivors are not ready to use web-based questionnaires because of their age, that survivors were too sick to fill out the questionnaires or that survivors did not want to be confronted with the ICU admission.

According to the health professionals, if follow-up care is offered on a voluntary basis, some survivors will reject it (28.6%). Lack of interest, avoidance as part of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), distance to hospital, burden to ask caregivers for support are frequently stated reasons by the health professionals for survivors to reject ICU follow-up care. Most health professionals (85.7%) would like to see follow-up care as part of the routine care, only few health professionals think of the follow-up care as an extra service to the survivor.

Questionnaire outcomes of the ICU survivors

In total, 54 survivors filled out the web-based questionnaires and 74 survivors used the paper-based version. Eighty-seven survivors attended ICU follow-up care. Table 3 gives an overview of characteristics of survivors, grouped by paper-based or web-based data collection. Survivors who preferred web-based questionnaires were significantly younger compared with survivors who filled out the paper-based questionnaires (p<0.05) and had a longer ICU stay (p<0.05). Survivors who filled out the web-based questionnaires had a significant higher prevalence of PTSD, measured with the Trauma Screening Questionnaire. For all other patient-reported outcomes, there were no significant differences between survivors who filled out the web-based questionnaires as opposed to survivors who filled out paper-based questionnaires.

Table 3.

Characteristics of ICU survivors who returned the questionnaires

| Web-based questionnaire (n=54) |

Paper-based questionnaire (n=74) |

P values* | |

| Male n (%) | 29 (53.7) | 35 (47.3) | 0.59 |

| Age | 60.5 (52.3; 67.5) | 69.5 (54.5; 75.1) | <0.05 |

| Type of ICU admission | |||

| Medical n (%) | 46 (85.2) | 58 (78.4) | 0.43 |

| Surgical n (%) | 4 (7.4) | 5 (6.8) | |

| Emergency surgery n (%) | 4 (7.4) | 11 (14.9) | |

| ICU length of stay | 11.8 (6.5; 20.7) | 9.6 (5.9; 16.9) | <0.05 |

| Hospital length of stay | 21.0 (14.5; 37.5) | 22.0 (14.0; 31.0) | 0.45 |

| Mechanical ventilation days | 5.6 (4.0; 12.1) | 4.9 (3.4; 8.5) | 0.08 |

| APACHE IV score† | 70.0 (56.5; 82.0) | 73.5 (60.5; 88.8) | 0.13 |

| Questionnaires | |||

| HADS | 0 missing | 5 missing | |

| Anxiety n (%) ≥8 | 20 (37) | 17 (24.6) | 0.14 |

| Depression n (%) ≥8 | 15 (27.8) | 22 (31.9) | 0.66 |

| TSQ | 2 missing | 4 missing | |

| n (%) ≥6 | 15 (28.8) | 10 (14.3) | <0.05 |

| SF-36 | 0 missing | 8 missing | |

| Mental component | 48.4 (36.5; 53.6) | 47.9 (39.8; 53.8) | 0.44 |

| Physical component | 34.6 (25.1; 42.1) | 37.6 (30.2; 44.4) | 0.21 |

| MUST | 4 missing | 22 missing | |

| n (%) ≥1 | 27 (50) | 24 (32.4) | 0.43 |

*Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data, t-test for normally distributed data and χ2 test for categorical data.

†Only calculated for the ICU survivors which met the APACHE IV inclusion criteria.

APACHE IV, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ICU, intensive care unit; MUST, Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool; SF-36, Short From 36; TSQ, Trauma Screening Questionnaire.

In the paper-based group, less questionnaire outcomes could be calculated due to missing items, that is, in the paper-based group 13.2% of the results were missing, in the web-based questionnaire group this was 2.8%.

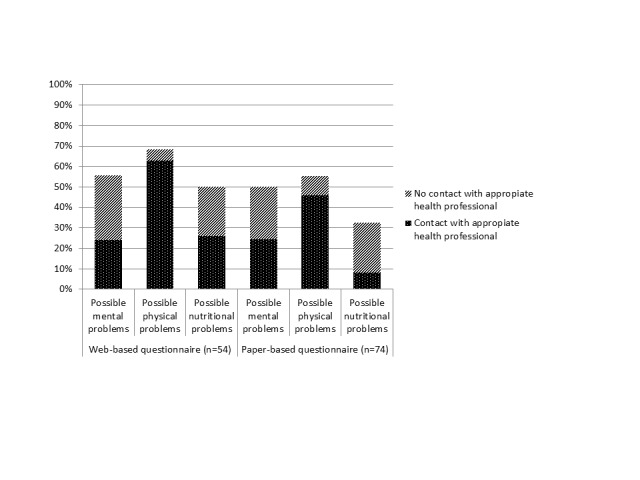

Within both questionnaire groups, there was a large prevalence of possible mental problems, physical problems and nutritional problems (table 3 and figure 1). Not all survivors with possible problems had contact with the appropriate health professionals during the time of filling out the questionnaires.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of possible mental problems, physical problems and nutritional problems.

Discussion

We implemented a web-based triage tool to evaluate its feasibility and to assess the outcomes of web-based questionnaires compared with paper-based questionnaires. In previous literature, the benefits of web-based screening software have been pointed out in clinical trial settings.10 However, our study showed that the implementation in daily practice might be difficult and we identified important barriers to consider. Survivors who responded to the web-based questionnaires were significantly younger and had a significantly longer ICU stay than those who preferred the paper-based questionnaires. Health status at the time of filing out the questionnaire did not differ between the two groups. Strikingly, the prevalence of mental, physical and nutritional problems was equally high in both groups and the majority did not receive care for these complaints before they visited the ICU follow-up clinic.

Though the tool was evaluated and adjusted before implementation, eight (57.1%) health professionals found the software too complex to use. The average SUS score was 56, indicating a less than average usability and necessitating improvement of the software. A point of interest is the time between the training and the start of the pilot study. Not all ICU follow-up clinics started the pilot study at the same time, while the training was given on three dates during two consecutive weeks. Moreover, during the evaluation the pilot study, five health professionals mentioned that they used the software so little, they forgot how to send an email with it. For future research, it is advised to plan the training shortly before the start of the study and to use the new software on a regular basis.

Over 40% of the respondents filled out the web-based questionnaires. Health professionals stated that many survivors did not have an email address and expressed that survivors in general are not ready yet to use the web-based triage tool because of their age. This was not in line with the results of the telephone calls where only one (3.6%) survivor stated that they did not had an email address. Moreover, as our society is focussing and relying more and more on digital systems, survivors not having an email address will be no barrier in the future. Already in 2013, 95% of all Dutch households had access to a computer with an internet connection.19

Digitally issued questionnaires have major benefits compared with paper-based questionnaires, such as more complete data, less entry errors and easy storage of data.8 Our study confirmed this finding as we found that in the paper-based questionnaire group, there was more information missing. A possible explanation can be the use of checks and prompts in the web-based questionnaires when items were not filled out. Another major benefit is that by using web-based screening software, survivors with possible health problems can be identified without visiting the hospital. The outcomes of the questionnaires can be used in clinical decision-making and tailored care. This will improve the effectiveness of the treatments.

The prevalence of possible mental, physical and nutritional problems was high among the respondents. However, not all survivors received the appropriate care after hospital discharge. Even though there is no consensus on the (cost-) effectiveness of intensive care follow-up programmes,20–22 we believe that our triage tool is a step in the right direction. Follow-up care should be offered as stepped care, so it can be tailored to the needs of survivors. The triage tool makes it possible to highlight the problem areas so they can be addressed during consultation. Furthermore, the triage tool can be used to reach large groups of survivors as the data collection and processing is less labour intensive.

People choosing to fill out questionnaires online were significantly younger compared with those preferring paper-based questionnaires.23 According to previous published studies, younger age has been found to be a risk factor for PTSD24 and a prolonged hospital stay is associated with lower mental or physical quality of life.25 In our study, survivors who used the web-based questionnaires were also younger compared with survivors in the paper-based group and had a longer ICU stay. This can be a possible explanation for the finding that survivors in the web-based questionnaire group had a significantly higher risk of developing PTSD compared with survivors in the paper-based group.

A strength of this study was the use of mixed methods, that is, qualitative and quantitative methods. By using mixed methods, we were able to verify the statements of health professionals with the clinical data and questionnaire outcomes of survivors. For example, health professionals stated that a large part of survivors did not have an email address and that survivors were sometimes not able to fill out questionnaires due to their health status. However, these concerns were not validated with the phone calls. A possible explanation can be that survivors that could not been reached had the worst health status.26

Though 531 survivors were eligible for follow-up care, eventually only 128 survivors responded to the questionnaires. This is first due to the fact that only 221 of the 531 eligible survivors received an invitation to fill in the questionnaire and visit the follow-up clinic. A limitation of this study is that we have little information on why certain survivors were, and others were not, invited. During the interviews, the health professionals mentioned the absence of financial support from the department as a major problem. Some health professionals provide follow-up care in their own time, this makes it difficult to offer ICU follow-up care customarily. Second, of the 221 ICU survivors invited to fill out the questionnaires, 93 did not respond resulting in a response rate of 57.9%. A review conducted on the quality of life after ICU admission described that three (6%) of their included studies had a response rate of <50% and 24 studies (45%) had a response rate between 50% and 79%.2 In sight of this review, we consider the response rate of our study average.

During the interviews, all health professionals repeatedly stressed the importance of follow-up care for survivors, to address the burden these survivors suffer after their ICU admission. They all endorse the necessity and the benefits of ICU follow-up care, however, these ideas are not yet supported by scientific research. Filling out web-based questionnaires will have added value due to digitalising society. Questionnaire outcomes are present during consultation and can be discussed with survivors and their families. The results of these web-based questionnaires can be used to gain insight in the efficiency of the ICU follow-up care, if stored in a national database with options to benchmark the long-term outcomes of survivors.

Conclusions

Web-based screening software has major benefits compared with paper-based screening, however, the implementation has shown to be difficult and there are important barriers to consider. In order to successfully implement a new web-based triage tool, health professionals need time and support to use it. The email addresses should be queried at hospital admission so that it will not be necessary to collect the email address after hospital discharge. In both web-based and paper-based population, there was a large prevalence of survivors with possible mental, physical and nutritional problems and we suggest ICU follow-up care in order to address these problems. We think that our software is a starting point of making ICU follow-up care feasible and effective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all ICU survivors and health professionals of the participating hospitals who were willing to participate in this study. We would like to thank ItéMedical for all services provided with respect to the development of the web-based triage tool and the technical support during the pilot study.

Footnotes

Contributors: IvB gave the training to use the triage tool, conducted all semistructured interviews with the health professionals, transcribed the interviews verbatim, coded the interviews and drafted the manuscript. FB-R gave the training to use the triage tool, coded the interviews and helped to draft the manuscript. NFdK participated in the design and coordination of this study. DAD helped in analysing and interpreting the results. MvdS participated in the design and coordination of this study. All authors discussed the themes and statements of the coding, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The NICE registry is registered according to the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act. The need for ethical approval for this study was waived by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center and stored under number W17-354.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We obtained permission from the research board of the NICE registry and the participants to use data at the time of the study. The NICE board assesses each application to use the data on the feasibility of the analysis and whether or not the confidentiality of patients and ICUs will be protected. To protect confidentiality, raw data from ICUs are never provided to third parties. For the analyses described in this paper, we used an anonymised dataset. The use of anonymised data does not require informed consent in the Netherlands.

References

- 1. Angus DC, Carlet J. 2002 Brussels Roundtable Participants. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:368–77. 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, et al. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 2010;38:2386–400. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3dec5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA, et al. Functional status after intensive care: a challenge for rehabilitation professionals to improve outcome. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:360–6. 10.2340/16501977-0333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tan T, Brett SJ, Stokes T. Guideline Development Group. Rehabilitation after critical illness: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2009;338:b822 10.1136/bmj.b822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korkeila K, Suominen S, Ahvenainen J, et al. Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. Eur J Epidemiol 2001;17:991–9. 10.1023/A:1020016922473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA, et al. Poor functional recovery after a critical illness: a longitudinal study. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:1041–8. 10.2340/16501977-0443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Gelder MMHJ, Bretveld RW, Roeleveld N. Web-based Questionnaires: The Future in Epidemiology? Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:1292–8. 10.1093/aje/kwq291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coons SJ, Eremenco S, Lundy JJ, et al. Capturing Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Data Electronically: The Past, Present, and Promise of ePRO Measurement in Clinical Trials. Patient 2015;8:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox CE, Wysham NG, Kamal AH, et al. Usability Testing of an Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome System for Survivors of Critical Illness. Am J Crit Care 2016;25:340–9. 10.4037/ajcc2016952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van der Schaaf M, Bakhshi-Raiez F, Van der Steen M, et al. Recommendations for the organization of intensive care follow-up clinics; report from a survey and conference of Dutch intensive cares. Minerva Anestesiol 2015;81:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van de Klundert N, Holman R, Dongelmans DA, et al. Data resource profile: the Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) Registry of Admissions to Adult Intensive Care Units. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1850 10.1093/ije/dyv291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. NICE. Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) registry. http://www.stichting-nice.nl (accessed 08 Nov 2016).

- 14. Mahieu GR. Follow-up system for intensive care patients: preliminary evaluation of workflow and usability. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boren T, Ramey J. Thinking aloud: reconciling theory and practice. IEEE Trans Prof Commun 2000;43 261–78. 10.1109/47.867942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brooke J. SUS: A Quick and Dirty Usability Scale : Usability evaluation in industry. London: Taylor & Francis, 1996:189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 18. IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS). Statline, 2017. (accessed 01 Feb 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK, et al. The practical study of nurse led, intensive care follow-up programmes for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;339:b3723 10.1136/bmj.b3723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. Rehabilitation after critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2456–61. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000089938.56725.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elliott D, McKinley S, Alison J, et al. Health-related quality of life and physical recovery after a critical illness: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a home-based physical rehabilitation program. Crit Care 2011;15:R142 10.1186/cc10265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zuidgeest M, Hendriks M, Koopman L, et al. A comparison of a postal survey and mixed-mode survey using a questionnaire on patients' experiences with breast care. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e68 10.2196/jmir.1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:748–66. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baldwin FJ, Hinge D, Dorsett J, et al. Quality of life and persisting symptoms in intensive care unit survivors: implications for care after discharge. BMC Res Notes 2009;2:160 10.1186/1756-0500-2-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Unroe M, Kahn JM, Carson SS, et al. One-year trajectories of care and resource utilization for recipients of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2010;153 167 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1055–68. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brewin CR, Rose S, Andrews B, et al. Brief screening instrument for post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:158–62. 10.1017/S0007125000161896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elia M. Screening for malnutrition: a multidisciplinary responsibility. Development and use of the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (‘MUST’) for Adults. Redditch: BAPEN, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021249supp001.pdf (93.8KB, pdf)