Abstract

Introduction:

The complex relationships among HIV knowledge, condom-use skills, self-efficacy, peer influence and intention to use condoms have been rigorously investigated. However, studies guided by a linear behavior change model often explain only a limited amount of variances. This study aims to advance our understanding of the relationships through a nonlinear quantum change paradigm.

Methods:

Data (n=1970, 40.61% male, mean age 16.94±0.74) from a behavioral intervention program among high school students in the Bahamas were analyzed with a chained cusp catastrophe model in two steps. In the first step, self-efficacy was analyzed as the outcome with HIV knowledge/condom-use skills as asymmetry variables and peer influence as bifurcation variable. In the second step, condom-use intention was analyzed as the outcome while self-efficacy (outcome in the first step) was used as bifurcation variable allowing peer influence as bifurcation, and HIV knowledge/condom-use skills were included as asymmetry. Cusp modeling analysis was conducted along with equivalent linear models.

Results:

The cusp model performed better than the linear and logistic models. Cusp modeling analyses revealed that peer influence significantly bifurcated the relationships between HIV knowledge/condom-use skills and self-efficacy; while both self-efficacy and peer influence significantly bifurcated the relationship between HIV knowledge/condom-use skills and condom-use intention.

Conclusion:

Our findings support the central role of self-efficacy and peer influence as two chains in bridging the complex quantum relationships between HIV knowledge/condom-use skills and condom-use intention among adolescents. The nonlinear cusp catastrophe modeling provided a new method to advance HIV behavioral research.

Keywords: Chained quantum change, Cusp catastrophe model, Adolescents, Condom-use intention, Peer influence, Self-efficacy

1. Introduction

1.1. Condom Use in HIV Prevention

HIV/AIDS has been one of the global public health challenges in the 21st Century (WHO, 2015, 2017). To prevent HIV transmission, condom-use has been considered as one of the evidence-based strategies (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Condom-use intention, an individual’s perceived likelihood to engage in using a condom during sexual intercourse, is an immediate predictor of actual condom use (X. Chen, Stanton, Chen, & Li, 2013). People with higher condom-use intention are more likely to use condoms during sex (X. Chen et al., 2013). Therefore, promoting the intention and actual use of condoms has been recommended and widely used as a strategy to control and prevent HIV infection and transmission.

Adolescence is a period in life characterized with an imbalance between physical growth and neuro-cognitive development because of an approaching-to-mature physical growth and a rapid developing cognitive capability (Goddings, Dumontheil, Blakemore, & Viner, 2014; Hartshorne & Germine, 2015). This imbalance renders adolescents a particularly vulnerable subpopulation to almost all health-related risk behaviors, including cigarette smoking (Xu & Chen, 2016), alcohol consumption (Clair, 1998), drug use (Mazanov & Byrne, 2006), and particularly sexual risk behaviors (X. Chen et al., 2010, 2013; Xu, Chen, Yu, Joseph, & Stanton, 2017). Engaging in unprotected sex increases the probability of HIV infection. A better understanding of condom-use intention and behavior is therefore of great importance for developing more effective and targeted interventions aimed at promoting condom use among adolescents and reducing the risk of HIV infection.

1.2. Quantum Change of Condom-use Intention

To date, theories and models guiding health behavioral research studies are based primarily on the continuous behavior change (CBC) paradigm (X. Chen & Chen, 2015; X. Chen, 2018; X. Chen et al., 2010, 2013; Xu & Chen, 2016). Under a CBC paradigm, changes in behavior are governed by rational and analytical thinking, thus they are assumed to be linear and continuous. For example, people with better knowledge regarding tobacco harm are more likely to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked after rational cost-effect analysis (Yan et al., 2014). However, not all characters of a behavioral dynamics can be explained by CBC, limiting our understanding of health behaviors (X. Chen & Chen, 2015; X. Chen, 2018). First, behavior changes do not always follow a linear and continuous pattern, and some of them show nonlinear and discrete change. For example, many smokers quit smoking suddenly without any analytical thinking, reflecting as a nonlinear and discrete process (West & Sohal, 2006). Other examples with nonlinear discrete changes include suicide ideation and attempts (Simon et al., 2002), sexual risk behaviors (X. Chen et al., 2010), and condom use (Donohew et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2017). Second, many theory-based behavioral studies have only explained a small amount of total variance (less than 25% of the total variance) (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Chaudoir, Fisher, & Simoni, 2011; Crepaz & Marks, 2002). Third, many well-designed and evidence-based intervention programs have only achieved a small-to-moderate effect sizes (Aldrich & Cerel, 2009; Berman, DA Jobes, & Silverman, 2006; X. Chen et al., 2009, 2010; Dinaj-Koci et al., 2014; Gong, Chen, & Li, 2015; Herbst et al., 2005; Kaljee et al., 2005; Michielsen, Chersich, Temmerman, Dooms, & Van Rossem, 2012; Noar, Black, & Pierce, 2009; Tan, Huedo-Medina, Warren, Carey, & Johnson, 2012).

To overcome the limitation of CBC, an alternative paradigm entitled as quantum behavior change (QBC) is proposed (X. Chen & Chen, 2015; X. Chen, 2018; Miller & C’de Baca, 2001; Resnicow & Page, 2008). According to QBC paradigm, not only a behavior change can, in general be predictable, gradual, linear and continuous, but it can also, in specific settings, be unexpected, sudden, nonlinear, and discrete (X. Chen et al., 2013). For example, when people decide to stop smoking cigarettes, some of them will try to reduce the number of cigarettes every day, and finally achieve the goal of cigarettes cessation gradually; on the other hand, some people may quit smoking immediately following the sudden and discrete pattern. QBC paradigm incorporates both change patterns into one theoretical framework, making one step further to capture the nature of human behaviors. A number of studies have applied QBC paradigm to understand different health behaviors, including tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, drug abuse, unprotected sex, and intention to use condom during sex (Byrne, Mazanov, & Gregson, 2001; X. Chen et al., 2010, 2013; Clair, 1998; Stephen J Guastello, Aruka, Doyle, & Smerz, 2008; Mazanov & Byrne, 2006; Xu et al., 2017; Xu & Chen, 2016). The main purpose of the study is to apply the QBC paradigm to investigate the quantum change of intention to use condom and the influential factors among youth in the Bahamas.

1.3. Dual Process Theory of Condom-use Intention

Through the QBC paradigm, we are able to observe the complex phenomena of human behaviors, however, it is still not clear why behaviors can present both linear and non-linear change. Theories from biological and cognitive perspectives are strongly needed to explain QBC of human behaviors. After reviewing the literatures, Dual Process Theory (DPT) was successfully located to represent a promising cognitive theory for QBC-based research (Evans, 2003; Kahneman, 2003; Xu et al., 2017). As a cognitive theory, DPT posits two different cognitive systems (System 1 and System 2, see Figure 1) in aiding behavioral decision making. System 1 represents a general and universal cognition process in charge of intuitive, impulsive, and implicit decision making (Evans, 2003). The decision-making process operated through System 1 is thus fast, cognitively less demanding, and often activated by contextual factors (Kahneman, 2003). Therefore, the dynamics of behavior changes governed by System 1 is nonlinear, sudden, and discrete. For example, an adolescent may simply use a condom during sexual intercourse without analytical thinking if he/she knows that most of his/her peers use condoms and/or is requested by his/her partner.

Figure 1.

Dual Process Theory and Quantum Behavior Change

In contrast, the cognitive process in System 2 is typically logic, rule- based, involving detailed reasoning, and explicit analysis (Evans, 2003). Behavioral decision-making through System 2 is thus gradual, time-consuming, cognitively more demanding (Kahneman, 2003). Therefore, the dynamics of behavioral change governed by System 2 will be gradual, linear and continuous; and System 2 is often activated by questions and requires for adequate amount of time, information, and reasoning and analytical capability to function (X. Chen & Chen, 2015; X. Chen et al., 2013). A typical example of behavioral changes through System 2 could be that an adolescent has decided to use condom during sex after comparing the pros and cons of condom when facing the challenge of HIV infection and knowing that condom could be an effective method to protect him/her from being infected by HIV or passing the virus to his/her partner.

1.4. QBC-guided Cusp Catastrophe Modeling

While DPT is applied to explain the QBC of human behaviors, a new challenge appears. Traditional statistical methods (e.g. linear and logistic regression) are unable to handle the QBC-based dual characters in one model. To address the limitation, cusp catastrophe model was developed to provide an alternative for human behaviors (D. Chen, Lin, Chen, Tang, & Kitzman, 2014; X. Chen & Chen, 2015) (Figure 2). Catastrophe models, belonging to nonlinear dynamic system, are developed to describe complex natural and social phenomena, such as earthquake, hurricane and social turmoil (Gilmore, 1993; S J Guastello, 2001; Thom, 1975). According to the number of control variables, seven elementary catastrophe models are developed (Gilmore, 1993; Thom, 1975). Cusp catastrophe model is one widely used catastrophe model with two control variables (i.e. asymmetry variable and bifurcation variable) (Stephen J Guastello et al., 2014; Ramos-Villagrasa, Marques-Quinteiro, Navarro, & Rico, 2018; Zeeman, 1976). To advance researches in human behaviors, we have applied cusp model to simultaneously characterize both a continuous and linear and a discrete and nonlinear character of behaviors (D. Chen, Chen, & Zhang, 2016; D. Chen et al., 2014; X. Chen et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2017; Xu & Chen, 2016). As shown in Figure 2, the equilibrium plane of a cusp catastrophe depicts the status of an outcome variable z along with changes in two predictor variables: asymmetry variable x and bifurcation variable y corresponding to the following mathematical model:

| (1) |

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagram of cusp catastrophe model in addressing QBC paradigm

The equilibrium plane contains two stable regions (lower and upper panel) and one unstable region (cusp region). Three paths (A, B and C) in the figure represent three typical change patterns of an outcome variable z along with changes in x and y. Path A depicts that when y < O, the relationship between x and z is linear and continuous. Path B shows that when y > O, with the increase in x passes threshold O-Q, the outcome z will suddenly jump from the lower stable region to the upper stable region. For Path C, when decrease in x passes the threshold line O-R, outcome z will suddenly drop from the upper stable region to the lower stable region. Thus changes in y can bifurcate the relationship between the asymmetry variable x and the outcome z. By connecting QBC paradigm with DPT in cusp catastrophe modeling, we can see that an asymmetry variable characterizes the part related to linear and continuous dynamic changes operated through System 2, and a bifurcation variable captures the part related to nonlinear and discrete dynamic changes operated through System 1. Application of the cusp catastrophe model guided by QBC will thus deepen our understanding of heath behavior change dynamics with potentials to provide new evidence for more effective and more precision interventions for risk reduction.

1.5. Construction of Cusp Catastrophe Models for Condom-use Self-efficacy

It has been well established that HIV knowledge and condom-use skills are positively associated with self-efficacy to use condom (Mahat, Scoloveno, & Scoloveno, 2016; Wulfert & Wan, 1993). An adolescent with greater HIV knowledge and more condom-use skills is more confident in using condoms during sex and more capable of persuading his/her partner to use condoms (Mahat et al., 2016). In addition, adolescents who perceived more condom-use among peers have greater self-efficacy for condom-use (Caron, Godin, Otis, & Lambert, 2004; Wulfert & Wan, 1993). According to DPT, the relationship of HIV knowledge and condom-use skills with self-efficacy could be continuous and linear, and the impact of peer influence on self-efficacy could be nonlinear and discrete. In a cusp catastrophe model with condom-use self-efficacy as outcome, HIV knowledge and condom-use skill will be best modeled as asymmetry variable, and peer influence as bifurcation variable. We termed this model as Quantum Change I.

1.6. Construction of Cusp Catastrophe Models for Condom-use Intention

HIV knowledge and condom-use skills play important roles in fostering condom-use intention (X. Chen et al., 2013). Adolescents with greater HIV knowledge and more condom-use skills are more likely to use condoms, and/or persuade their partner(s) to use condoms (Ajzen, 2011; X. Chen et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2008; Dinaj-Koci et al., 2014; Li, Li, Wang, Shao, & Dou, 2014; Taggart et al., 2016). According to DPT, these behavioral theory-based relationships between condom-use intention and HIV knowledge and condom-use skills are most likely to be processed by System 2. Therefore, the resultant changes in condom-use intention will be continuous and linear (X. Chen et al., 2013) and these two variables would best be modeled as asymmetry variables.

Condom-use self-efficacy is the self-assuredness to use or persuade partners to use condoms during sex (Baele, Dusseldorp, & Maes, 2001; X. Chen et al., 2013). Previous study indicated that condom-use self-efficacy was significantly related to both intention and actual use of a condom among high school students (Baele et al., 2001). In addition, peer influence plays a critical role in behavioral change. Engaging in a peer group is a developmental expectation for adolescents when they enter middle or high school (Santor, Messervey, & Kusumakar, 2000). Conformity with a group’s interests and behavioral patterns enhances the acceptance of an adolescent by the group (Santor et al., 2000; Selikow, Ahmed, Flisher, Mathews, & Mukoma, 2009). Therefore, peer influence as a contextual factor may exert significant impact on adolescent’s behavior, including condom use (Santor et al., 2000; Selikow et al., 2009). Adolescents in a group of peers with norms and behaviors pro-condom use are more likely to have intention to use a condom during sex (Crockett, Raffaelli, & Shen, 2006). According to DPT, both condom use self-efficacy and peer influence affect intention to use a condom primarily through System 1. Therefore, dynamic changes in condom-use intention with regard to these two factors could be nonlinear and discrete (X. Chen et al., 2013). Therefore these two factors will best be modeled as bifurcation variable. We termed this model as Quantum Change II.

1.7. A Chained Model Linking Condom Self-efficacy with Condom-use Intention

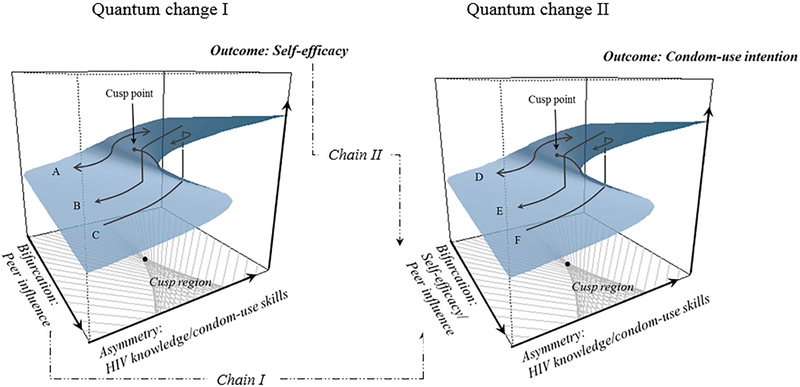

We purposefully constructed the two cusp models, Quantum Changes I and II as presented in Sections 1.5 and 1.6, so that they are conceptually linked together by shared predictors and outcome variables as chains (Figure 3). In Quantum Change I, HIV knowledge and condom use skills are asymmetry variables, and peer influence is bifurcation variable with condom use self-efficacy as outcome variable. In Quantum Changes II, asymmetry variables remain the same, peer influence and self-efficacy, the outcome variable in Quantum Change I, are bifurcation variables predicting the intention to use condom. These variables link the two models together with three potential chains. As shown in the Figure 3, Chain I is linked through one variable peer influence (bifurcation variable for both Quantum Changes I and II); and Chain II is developed through self-efficacy (the outcome in Quantum Change I and the bifurcation in Quantum Change II).

Figure 3.

Cusp catastrophe modeling analysis to test the proposed chained quantum change linking HIV knowledge, condom-use skills, self-efficacy and peer influence with condom-use intention (also see Figure 1).

Note: In Quantum Change I, line A is an example of continuous change and lines B and C are examples of discrete changes in condom self-efficacy; likewise, D, E, F represent another three example lines in Quantum Change II in explaining changes in condom use intention

If the proposed chained cusp model can be verified with the data, it will deepen our understanding of condom use behaviors, and their relationship with different predictors. If the Quantum Change I is verified, the peer influence will play an important role in the promoting the sudden change of condom use self-efficacy. On the other hand, if the Quantum Change II is created, and confirmed by the data, both peer influence and self-efficacy will contribute significantly to the sudden and discrete change of intention to use condom. To promote the condom use intention among youth, both peer influence and self-efficacy are the targets for intervention, while peer influence is the key to increase the self-efficacy in the first part of the chained quantum change model. Thus if the data is successfully fit the proposed chained quantum change model, more efforts of intervention in the future may be placed on the changing of environmental factor perceived peer influence and intrapersonal factor self-efficacy.

1.8. Purpose of This Study

This study aims at testing the hypothesized chained quantum change model (Figure 3) with data from a large behavioral intervention trial for HIV prevention among adolescents. The purpose of this analysis is to provide new data advancing our understanding of the mechanism of condom-use, potentially providing evidence strengthening intervention research with a focus on self-efficacy and peer influence to promote condom-use in adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sampling

The participants in this study were high school students enrolled in a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the Bahamian Focus on Older Youth (BFOOY) in reducing risk behaviors for HIV prevention. Confronting a major HIV epidemic since 1990’s, the Bahamas has developed aggressive prevention and treatment programs to combat the disease (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on HIV Prevention Strategies in the United States, 2001). BFOOY is one of such programs that has been developed based on a previous intervention that had shown to be effective in promoting HIV protective behaviors and discouraging HIV risk behaviors among middle school students in the Bahamas (X. Chen et al., 2013; Dinaj-Koci et al., 2014).

Details of the program BFOOY were described elsewhere (Dinaj-Koci et al., 2015). In brief, all eight government funded high schools in New Province, the largest island in the Bahamas, were invited and agreed to participate in the trial. Only the students who returned the signed consent forms were enrolled into the trial (Dinaj-Koci et al., 2014, 2015). Data from the 24-month post-intervention evaluation were included for this analysis. We selected this wave of data because more students at this period were sexually active than at earlier periods, and more of them might have experienced changes in attitudes and behaviors with regard to HIV/AIDS (X. Chen et al., 2013). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida.

2.2. Measurement

Condom-use intention

Condom-use intention was used as the outcome variable, and it was assessed based on participants’ response to the question “How likely is it that you will use a condom if you were to have sex in the next six months?” A five-point Likert scale was used to assess the levels of intention (1 = No, 2=Probably not, 3=Don’t know, 4=Maybe and 5=Yes). The response scores were used in analysis with higher scores indicating greater intention to use condoms.

Condom-use self-efficacy

Condom-use self-efficacy was assessed using a six-item scale measuring the perceived ability to obtain, use, and/or convince sex partners to use, to ask for condom in a store or clinic, and to refuse to have sex without condom. A typical item is “I could convince my partner that we should use a condom even if he (she) doesn’t want to”. A 5-point Likert scale was used to assess the scale with “1=No, I could not” to “5=Yes, I could”. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.81. Mean scores were computed based on participants’ responses to the six items such that larger scores indicating higher condom-use self-efficacy. In Quantum Change model I, this variable was used as the outcome. In Quantum Change model II, it was used as a bifurcation variable as in reported studies (Xu et al., 2017). According to DPT, the impact of self-efficacy on condom-use intention might be processed intuitively through System 1.

Peer influence

Peer influence was assessed using a three-item scale measuring the personal perception of peer condom-use when having sex with partners. The three items were “Of your close friends who have had sex, how many use condoms?”, “Of the boys you know who have had sex, how many use condoms?” and “Of the girls you know who have had sex, how many make sure their partner is using a condom?” Each item was assessed using a three-point Likert scale with “1=None used condoms”, “2=Some” and “3=Most”. The alpha for this study was 0.73, and mean scores were calculated based on responses to the three questions with higher scores indicating perceptions of more peers using condoms. Guided by DPT, peer influence was modeled as the bifurcation variable since it represents an important contextual factor and its impact is more likely to be processed intuitively through System 1.

HIV knowledge

This asymmetry variable was assessed using 18 true/false statements regarding the transmission, prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. Typical items are “There is a female condom that can help decrease a woman’s chance of getting HIV” and “Bush medicine can cure AIDS”. One point was assigned for each correct answer with a score range of 0 to 18 with higher scores indicating more knowledgeable about HIV/AIDS. This variable was modeled as asymmetry because its impact, according to DPT, is operated analytically through System 2.

Condom-use skills

Condom-use skills were also used as asymmetry variable. This variable was assessed using a checklist consisting 16 items regarding steps of appropriate use of a condom. Typical items were “Withdraw the penis while it is still erect by holding the condom firmly in place, remove the condom.” and “Unroll the condom before placing it on the penis”. One point was assigned to a participants for each correct answer. The assigned scores ranged from 0 to 16 with higher scores indicating better condom skills. Like HIV knowledge, this variable was modeled as asymmetry because its impact is more likely to be operated via System 2.

Demographic variables

Age (in years) and gender (male/female) were included in the analysis to describe the study sample and to use as covariates in modeling analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency, rate, mean and standard deviation) were used to describe the sample characteristics. The relationships among four predictor variables (HIV knowledge, condom-use skills, peer influence, condom-use self-efficacy) and the two outcome variable condom-use intention were examined first using the conventional CBC-based approach. Linear regression was conducted to explore the relationships between the predictor and the outcome variables.

The proposed chained quantum model (Figure 3) was tested employing cusp catastrophe modeling method guided by QBC. Cusp model uses a curved surface with two control variables (asymmetry and bifurcation) to describe the QBC in condom-use self-efficacy (Quantum I) and condom-use intention (Quantum II). When moving from any area on the surface, change in self-efficacy in Quantum I or condom-use intention in Quantum II manifests as discrete if it goes across the cusp region (Lines B and C); otherwise continuous (Line A) (Figure 3).

A set of six constructed cusp catastrophe models were used to test the proposed chained quantum models in two steps. In the first step, two cusp models were used to assess the effect of peer influence in bifurcating the relationship (1) between the HIV knowledge (asymmetry) and self-efficacy, and (2) between condom-use skills (asymmetry) and self-efficacy. In the second step, four cusp models were tested. Two models were used to assess the effect of self-efficacy in bifurcating the associations (1) between HIV knowledge and condom-use intention, and (2) between condom-use skills and condom-use intention, respectively; and two models were used to assess the effect of peer influences in bifurcating the same two associations.

These constructed cusp models were assessed with the R package “cusp” in which model parameters were estimated by employing the Cobb’s maximum likelihood method (Grasman, Maas, & Wagenmakers, 2009). For comparison purposes, a fitted cusp model was compared with models of linear and logistic regression. Three indices were used to assess data-model fit: R2, Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Models with higher R2, smaller AIC and BIC were considered better (X. Chen et al., 2010; Cobb, 1998; Grasman et al., 2009).

Descriptive analyses, correlation and regression analyses were conducted using the commercial software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Cusp catastrophe modeling analyses were completed using the open source software R version 3.2.4 (R Development Core Team).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Sample

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study sample. Among the 1970 participants included, 40.61% were male, aged from 16 to 19 with a mean age of 16.94 (SD=0.74) years. The mean scores were 14.29 (SD=2.39) for HIV knowledge, 11.96 (SD=2.19) for condom-use skills, 2.39 (SD=0.47) for peer influence and 4.36 (SD=0.80) for self-efficacy, respectively. Of the total sample, 36.15% reported having had sex in the past six months, and 77.54% reported having intention to use condom (75.35% for male, 79.05% for female).

Table 1.

Characteristics and key measurements of the study sample

| Variables | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 800(40.61) | 1170(59.39) | 1970 (100.00) |

| Age in years, n (%) | |||

| 16 | 207 (25.88) | 330(28.21) | 537 (27.26) |

| 17 | 420 (52.50) | 643 (54.96) | 1063 (53.96) |

| 18 | 144(18.00) | 167(14.27) | 311(15.79) |

| 19 | 29 (3.63) | 30 (2.56) | 59 (2.99) |

| Mean (SD) | 16.99 (0.76) | 16.91 (0.72) | 16.94(0.74) |

| HIV knowledge | |||

| Mean (SD) | 14.01 (2.58) | 14.48 (2.23) | 14.29 (2.39) |

| Range | 0–18 | 1–18 | 0–18 |

| Condom-use skills | |||

| Mean (SD) | 12.10(2.18) | 11.87(2.19) | 11.96(2.19) |

| Range | 1–16 | 4–16 | 1–16 |

| Peer influence | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.42 (0.50) | 2.37 (0.45) | 2.39 (0.47) |

| Range | 1–3 | 1–3 | 1–3 |

| Condom use self-efficacy | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.58 (0.70) | 4.21 (0.84) | 4.36 (0.80) |

| Range | 1–5 | 1–5 | 1–5 |

| If had sex in past six month | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 350 (44.08) | 357 (30.72) | 707(36.15) |

| Condom-use intention, n (%) | |||

| No | 68 (8.55) | 113(9.74) | 181 (9.26) |

| Probably not | 10(1.26) | 4 (0.34) | 14 (0.72) |

| Don’t know | 60 (7.55) | 53 (4.57) | 113(5.78) |

| Maybe | 58 (7.30) | 73 (6.29) | 131 (6.70) |

| Yes | 599 (75.35) | 917(79.05) | 1516(77.54) |

3.2. Relationships between the Predictors and the Outcome Variable

Results in Table 2 indicate that HIV knowledge (beta estimate=0.07, p<0.001), condom-use skills (beta estimate=0.08, p<0.001), and peer influence (beta estimate=0.30, p<0.001) were significantly associated with condom use self-efficacy. Further, HIV knowledge (beta estimate=0.07, p=0.05), condom-use skills (beta estimate=0.05, p<0.001), peer influence (beta estimate=0.50, p<0.001) and condom use self-efficacy (beta estimate=0.47, p<0.001) were significantly related with condom-use intention.

Table 2.

Results from seven linear regression models assessing the relationship between the key predictor variables and (1) self-efficacy and (2) condom-use intention

| Predictor variables | N | Beta estimate [95% CI] | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Condom-use Self-efficacy | |||

| HIV knowledge | 1965 | 0.07 [0.06, 0.08] | <.0001 |

| Condom-use skills | 1905 | 0.08 [0.06, 0.09] | <.0001 |

| Peer influence | 1786 | 0.30 [0.23, 0.37] | <.0001 |

| Outcome: Condom-use intention | |||

| HIV knowledge | 1955 | 0.07 [0.05, 0.10] | <.0001 |

| Condom-use skills | 1896 | 0.05 [0.03, 0.08] | <.0001 |

| Peer influence | 1777 | 0.50 [0.39, 0.61] | <.0001 |

| Self-efficacy | 1950 | 0.47 [0.40, 0.54] | <.0001 |

Note: Seven linear regression models were used to assess each of the seven relationships. In each regression model, two demographic variables age and gender were included as covariates. Missing data existed in different variables, and no imputation was conducted.

3.3. Chained Quantum Modeling Analysis

Results in Table 3 indicate that all cusp models performed better than both linear and logistic regression models (higher R2, lower AIC and lower BIC for cusp models than for linear and logistic regression models). The estimated coefficients from Model 1 and Model 2 indicated that peer influences significantly and respectively bifurcated the relationship between HIV knowledge and self-efficacy and the relationship between condom-use skills and self-efficacy (beta estimate= 0.15, p<.001 for both).

Table 3.

Chained cusp catastrophe modeling of (1) self-efficacy and (2) condom-use intention

| Quantum I (2 models) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable/model | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| Outcome: Self-efficacy | ||||||

| Asymmetry | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.20** | Intercept | 1.24** | |||

| HIV knowledge | 0.17** | Condom skills | 0.24** | |||

| Bifurcation | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.16** | Intercept | 2.13** | |||

| Peer influence | 0.15** | Peer influence | 0.15** | |||

| Model fit | R2 | AIC | BIC | R2 | AIC | BIC |

| Cusp | 0.24 | 3324 | 3356 | 0.26 | 3306 | 3337 |

| Logistic | 0.04 | 4074 | 4100 | - | - | - |

| Linear | 0.04 | 4070 | 4091 | 0.05 | 4051 | 3338 |

| Quantum II (4 models) | ||||||

| Variable/model | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

| Outcome: Condom-use intention | ||||||

| Asymmetry | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.56** | Intercept | 0.55** | |||

| HIV knowledge | 0.07** | Condom skills | 0.05* | |||

| Bifurcation | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.81** | Intercept | 4.82** | |||

| Self-efficacy | 0.07* | Self-efficacy | 0.08* | |||

| Model fit | R2 | AIC | BIC | R2 | AIC | BIC |

| Cusp | 0.82 | 1195 | 1227 | 0.82 | 1204 | 1236 |

| Logistic | 0.05 | 4058 | 4085 | 0.05 | 4061 | 4087 |

| Linear | 0.04 | 4072 | 4093 | 0.03 | 4081 | 4102 |

| Variable/model | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||

| Outcome: Condom-use intention | ||||||

| Asymmetry | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.55** | Intercept | 0.55** | |||

| HIV knowledge | 0.07** | Condom skills | 0.05* | |||

| Bifurcation | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.89** | Intercept | 4.89** | |||

| Peer influence | 0.25** | Peer influence | 0.25** | |||

| Model fit | R2 | AIC | BIC | R2 | AIC | BIC |

| Cusp | 0.82 | 1153 | 1185 | 0.82 | 1161 | 1193 |

| Logistic | 0.04 | 4068 | 4094 | 0.04 | 4078 | 4104 |

| Linear | 0.04 | 4071 | 4092 | 0.03 | 4079 | 4100 |

Note: p<0.001

When the outcome variable self-efficacy in Models 1 & 2 was used as bifurcation variable in Models 3 & 4, self-efficacy significantly bifurcated the relationships between HIV knowledge and condom-use intention (beta estimate=.07, p<.05) and condom-use skills and condom-use intention (beta estimate=.08, p<.05). In addition to self-efficacy, results from Models 5 & 6 indicate that peer influence significantly bifurcated the relationship between HIV knowledge and condom-use intention and the relationship between condom-use skills and condom-use intention respectively, with beta estimate=0.25 and p<.01 for both.

4. Discussion

In this study, we tested a proposed a chained cusp catastrophe modeling approach in investigating the complex QBC relationships among four variables essential for promoting condom-use among adolescents. These variables were HIV knowledge, condom-use skills, condom-use self-efficacy, and peer influence. The proposed modeling approach was guided by DPT and analyzed with advanced cusp catastrophe modeling method. Findings of the study demonstrate the superiority of the QBC-based constructed cusp models over the CBC-based conventional linear and logistic regression models. The DPT-guided cusp catastrophe modeling method thus provides a powerful approach to investigate the complex relationship among these factors and changes in condom-use intention, which consists of a QBC dynamics with both a linear and continuous and a nonlinear and discrete component.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that dynamic changes in condom-use self-efficacy and intention to use a condom both are QBC in nature, consisting of, according to DPT, 1) a gradual, linear, and continuous process that is closely related to System 2; and 2) a sudden, nonlinear and discrete process that is closely related to System 1. Our findings on the QBC nature of self-efficacy of and intention to use condoms are consistent with those from previous research on various other health risk behaviors, including cigarette smoking (Xu & Chen, 2016), alcohol consumption (Stephen J Guastello et al., 2008), sexual initiation (X. Chen et al., 2010), and the condom use (X. Chen et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2017). What unique to our study was the application of DPT as guidance. With findings from this theory-guided research, we can conclude that intention to use condoms is highly context-oriented with strong impact from peers and self-efficacy, both of which are processed through System 1. Therefore, it would be more effective for condom use interventions to target on contextual factors in System 1 for sudden and intuitive change rather than knowledge and skills that are processed primarily through System 2 for gradual and reasoning-based changes.

Findings of the chained cusp modeling analysis also confirmed the role of HIV knowledge, condom-use skills, peer influence and self-efficacy in enhancing adolescents’ intention to use condom (X. Chen et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2008; Ford, Wirawan, Reed, Muliawan, & Sutarga, 2000; Li et al., 2014). The positive relationship between HIV knowledge/condom-use skills and condom-use self-efficacy intention could be bifurcated by peer influence. When peer influence level was low, the relationship was linear and continuous; when peer influence increased to certain levels, a small change in HIV knowledge/condom-use skills could trigger a sudden increase in adolescents’ self-efficacy for condom use. Likewise, peer influence and self-efficacy both could promote sudden increase (bifurcation) in the association between HIV knowledge/condom-use skills and condom-use intention. When the impact of peer influence or self-efficacy varies at low levels, the relationship between HIV knowledge/condom-use skills and condom-use intention was linear, gradual and continuous; when the impact of these two bifurcation variables was strong, a little increase in HIV knowledge/condom-use skills could make an adolescent with no intention to suddenly have strong intention to use condom.

Obviously, our chained modeling results support the central role of peer influence and self-efficacy, from a DPT-based QBC perspective, in predicting condom-use intention among U.S. adolescents. Although these two variables have been repeatedly shown to be related to intention and actual use of condoms (Baele et al., 2001; Caron et al., 2004), these studies were not guided by DPT. Peer influence is a contextual factor. When living in an environment with few peers, an adolescent’s decision to engage in a behavior may more likely be processed through System 2 – analytical, rational and gradual; when surrounded by peers, the same decision may more likely be operated through System 1 - non-analytic, intuitive, automatic and quick. Therefore, targeting peer influences to achieve sudden change would be a more effective educational strategy to promote condom use in adolescents. Since peer influence can bifurcate the relationship of knowledge/skills with a behavior, greater intervention effects can thus be achieved by simply altering the impact of peer influence to promote sudden changes.

Relative to peer-influences, self-efficacy represents an intrapersonal factor. Consistent with previous reported results, when self-efficacy level is low, accumulation of HIV knowledge and condom-use skills will play a major role, exerting a continuous and gradual effect on condom-use intention through System 2. However, when self-efficacy level is high, a little change in HIV knowledge and condom use skills may trigger a sudden increase in condom-use intention. Here self-efficacy plays a major role in promoting behavioral change through System 1 (X. Chen et al., 2013). Therefore, focusing on self-efficacy provide another approach to promote purposeful behavioral changes. Longitudinal studies guided by DPT and QBC are needed to verify these findings of our study.

In the chained cusp model, we successfully found that peer influence promotes the sudden change of self-efficacy while in turn both peer influence and self-efficacy promote the sudden change of condom use intention. Peer influence and self-efficacy linked the two cusp models together, presenting good targets for future effective intervention among youth. Additionally, relative to self-efficacy, peer influence may be more important as it promotes both quantum change of self-efficacy and the intention of condom use, and its effect on condom use intention is much greater than self-efficacy. Adolescents and young adults are much vulnerable to be influenced by the external environment, especially their peers surrounding them. The unbalancing between physical maturation and neuro-cognitive development may help explain this phenomena, and young people may not have strong capabilities to systematically analyze the behaviors by themselves, and would be more drove by the environment (X. Chen, Yu, Lasopa, & Cottler, 2017; Everett et al., 1999; Yu, Chen, & Wang, 2018). Therefore, interventions on the external environment may be a good option for preventing risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults.

There are limitations to this study. First, the original data were collected using questionnaire. Bias from self-report cannot be completely ruled out as indicated by the Cronbach alpha of the measurement instruments. Actual condom-use behavior was not used in the analysis because of the relatively fewer number of sexually active participants at the time of data collection. Second, only one wave of the study data were used, and cautions may be needed when inferencing the causal associations. Third, the cusp catastrophe is a new method in behavioral research, and further improvements are needed in the future. Despite the limitations, this study is the first to test a chained quantum change model with data from an important source. In addition to support findings from reported studies by others, this study added new knowledge to the current literature, and provided new data informing future research to better understanding adolescents’ behavior for HIV prevention.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was co-supported by the National Institute of Health/National Institute of Mental Health through two grant projects (R01 MH069229, Bonita Stanton and Xinguang Chen) and (R01 HD075635, Xinguang Chen and Din Chen).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Ajzen I (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich RS, & Cerel J (2009). The development of effective message content for suicide intervention: Theory of planned behavior. Crisis, 30(4), 174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, & Conner M (2001). Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analytic review. The British Journal of Social Psychology / the British Psychological Society, 40(Pt 4), 471–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baele J, Dusseldorp E, & Maes S (2001). Condom use self-efficacy: effect on intended and actual condom use in adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 28(5), 421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman AL, Jobes DA, & Silverman MM (2006). Adolescent suicide: Assessment and intervention. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne DG, Mazanov J, & Gregson RAM (2001). A cusp catastrophe analysis of changes to adolescent smoking behaviour in response to smoking prevention programs. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 5(2), 115–137. [Google Scholar]

- Caron F, Godin G, Otis J, & Lambert LD (2004). Evaluation of a theoretically based AIDS/STD peer education program on postponing sexual intercourse and on condom use among adolescents attending high school. Health Education Research, 19(2), 185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Condom use fact sheet in brief. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/brief.html

- Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD, & Simoni JM (2011). Understanding HIV disclosure: a review and application of the Disclosure Processes Model. Social Science & Medicine, 72(10), 1618–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Chen X, & Zhang K (2016). An exploratory statistical cusp catastrophe model. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) (pp. 100–109). IEEE. doi: 10.1109/DSAA.2016.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Lin F, Chen X, Tang W, & Kitzman H (2014). Cusp catastrophe model: a nonlinear model for health outcomes in nursing research. Nursing Research, 63(3), 211–220. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X (2018). Cognitive theories, paradigm in quantum behaviorchange, and cusp catastrophe modeling in social behavioral research:A system review. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Chen D (2015). Cusp catastrophe modeling in medical and health research In Chen D & Wilson J (Eds.), Innovative statistical methods for public health data (pp. 265–290). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lunn S, Deveaux L, Li X, Brathwaite N, Cottrell L, & Stanton B (2009). A cluster randomized controlled trial of an adolescent HIV prevention program among Bahamian youth: effect at 12 months post-intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 13(3), 499–508. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9511-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lunn S, Harris C, Li X, Deveaux L, Marshall S, … Stanton B (2010). Modeling early sexual initiation among young adolescents using quantum and continuous behavior change methods: implications for HIV prevention. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 14(4), 491–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stanton B, Chen D, & Li X (2013). Intention to use condom, cusp modeling, and evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention trial. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 17(3), 385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yu B, Lasopa S, & Cottler LB (2017). Current patterns of marijuana use initiation by age among US adolescents and emerging adults: implications for intervention. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(3), 261–270. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2016.1165239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K-H, Hoff C, Gregorich SE, Grinstead O, Gomez C, & Hussey W (2008). The efficacy of female condom skills training in HIV risk reduction among women: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1841–1848. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clair S (1998). A cusp catastrophe model for adolescent alcohol use: An empirical test. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 2(3), 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb L (1998). An introduction to cusp surface analysis Technical report, Aetheling Consultants, Louisville, CO, USA: URL http://www.aetheling.com/models/cusp/Intro.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, & Marks G (2002). Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: a review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS, 16(2), 135–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, & Shen Y (2006). Linking Self-Regulation and Risk Proneness to Risky Sexual Behavior: Pathways through Peer Pressure and Early Substance Use. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(4), 503–525. [Google Scholar]

- Dinaj-Koci V, Chen X, Deveaux L, Lunn S, Li X, Wang B, … Stanton B (2015). Developmental implications of HIV prevention during adolescence: Examination of the long-term impact of HIV prevention interventions delivered in randomized controlled trials in grade six and in grade 10. Youth & Society, 47(2), 151–172.doi: 10.1177/0044118X12456028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinaj-Koci V, Lunn S, Deveaux L, Wang B, Chen X, Li X, … Stanton B (2014). Adolescent age at time of receipt of one or more sexual risk reduction interventions. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(2), 228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohew L, Zimmerman R, Cupp PS, Novak S, Colon S, & Abell R (2000). Sensation seeking, impulsive decision-making, and risky sex: implications for risk-taking and design of interventions. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(6), 1079–1091. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00158-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JS (2003). In two minds: dual-process accounts of reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(10), 454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett SA, Warren CW, Sharp D, Kann L, Husten CG, & Crossett LS (1999). Initiation of cigarette smoking and subsequent smoking behavior among U.S. high school students. Preventive Medicine, 29(5), 327–333. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Reed BD, Muliawan P, & Sutarga M (2000). AIDS and STD knowledge, condom use and HIV/STD infection among female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS Care, 12(5), 523–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore R (1993). Catastrophe theory for scientists and engineers. Courier Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Goddings A-L, Dumontheil I, Blakemore S-J, & Viner R (2014). The relationship between pubertal status and neural activity during risky decision-making in male adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(2), S84–S85.24560082 [Google Scholar]

- Gong J, Chen X, & Li S (2015). Efficacy of a Community-Based Physical Activity Program KM2H2 for Stroke and Heart Attack Prevention among Senior Hypertensive Patients: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Phase-II Trial. Plos One, 10(10), e0139442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasman RP, Maas HLJ, & Wagenmakers EJ (2009). Fitting the cusp catastrophe in R: A cusp-package primer. Journal of Statistical Software, 32(8), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Guastello SJ (2001). Managing emergent phenomena: Nonlinear dynamics in work organizations. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guastello, Aruka Y, Doyle M, & Smerz KE (2008). Cross-cultural generalizability of a cusp catastrophe model for binge drinking among college students. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 12(4), 397–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastello Stephen J, Malon M, Timm P, Weinberger K, Gorin H, Fabisch M, & Poston K (2014). Catastrophe models for cognitive workload and fatigue in a vigilance dual task. Human Factors, 56(4), 737–751. doi: 10.1177/0018720813508777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne JK, & Germine LT (2015). When does cognitive functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the life span. Psychological Science, 26(4), 433–443. doi: 10.1177/0956797614567339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, DeLuca JB, Zohrabyan L, Stall RD, … Team HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis. (2005). A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 39(2), 228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on HIV Prevention Strategies in the United States. (2001). No Time To Lose: Getting More from HIV Prevention. (Ruiz MS, Gable AR, Kaplan EH, Stoto MA, Fineberg HV, & Trussell J, Eds.). Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). doi: 10.17226/9964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D (2003). A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. The American Psychologist, 58(9), 697–720. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaljee LM, Genberg B, Riel R, Cole M, Tho LH, Thoa LT, … Minh TT (2005). Effectiveness of a theory-based risk reduction HIV prevention program for rural Vietnamese adolescents. AIDS Education & Prevention, 17(3), 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Li X, Wang X, Shao J, & Dou J (2014). A cross-site intervention in Chinese rural migrants enhances HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitude and behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(4), 4528–4543. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110404528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahat G, Scoloveno MA, & Scoloveno R (2016). HIV/AIDS Knowledge, Self-Efficacy for Limiting Sexual Risk Behavior and Parental Monitoring. Journal of Pediatric Nursing-Nursing Care of Children & Families, 31(1), E63–E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanov J, & Byrne DG (2006). A cusp catastrophe model analysis of changes in adolescent substance use: assessment of behavioural intention as a bifurcation variable. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 10(4), 445–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michielsen K, Chersich M, Temmerman M, Dooms T, & Van Rossem R (2012). Nothing as practical as a good theory? The theoretical basis of HIV prevention interventions for young people in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR (William R, & C’de Baca J (2001). Quantum change: When epiphanies and sudden insights transform ordinary lives. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Black HG, & Pierce LB (2009). Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS, 23(1), 107–115. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Villagrasa PJ, Marques-Quinteiro P, Navarro J, & Rico R (2018). Teams as complex adaptive systems: reviewing 17 years of research. Small Group Research, 49(2), 135–176. doi: 10.1177/1046496417713849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, & Page SE (2008). Embracing chaos and complexity: a quantum change for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1382–1389. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santor DA, Messervey D, & Kusumakar V (2000). Measuring peer pressure, popularity, and conformity in adolescent boys and girls: Predicting school performance, sexual attitudes, and substance abuse. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(2), 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Selikow T-A, Ahmed N, Flisher AJ, Mathews C, & Mukoma W (2009). I am not “umqwayito’: a qualitative study of peer pressure and sexual risk behaviour among young adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 37 Suppl 2, 107–112. doi: 10.1177/1403494809103903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TR, Swann AC, Powell KE, Potter LB, Kresnow M, & O’Carroll PW (2002). Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32(s1), 49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart T, Taboada A, Stein JA, Milburn NG, Gere D, & Lightfoot AF (2016). AMP!: A Cross-site Analysis of the Effects of a Theater-based Intervention on Adolescent Awareness, Attitudes, and Knowledge about HIV. Prevention Science : The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 17(5), 544–553. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0645-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JY, Huedo-Medina TB, Warren MR, Carey MP, & Johnson BT (2012). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of HIV/AIDS prevention interventions in Asia, 1995–2009. Social Science & Medicine, 75(4), 676–687. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom R (1975). Structural stability and morphogenesis. New York, USA: Benjamin-Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- West R, & Sohal T (2006). Catastrophic” pathways to smoking cessation: findings from national survey. Bmj, 332(7539), 458–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2015). UNFPA, WHO and UNAIDS: position statement on condoms and the prevention of HIV, other sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregancy. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2015/july/20150702_condoms_prevention

- WHO. (2017). HIV/AIDS. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/

- Wulfert E, & Wan CK (1993). Condom use: A self-efficacy model. Health Psychology, 12(5), 346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, & Chen X (2016). Protection motivation theory and cigarette smoking among vocational high school students in China: a cusp catastrophe modeling analysis. Global Health Research and Policy, 1, 3. doi: 10.1186/s41256-016-0004-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Chen X, Yu B, Joseph V, & Stanton B (2017). The effects of self-efficacy in bifurcating the relationship of perceived benefit and cost with condom use among adolescents: A cusp catastrophe modeling analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 61, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Chen X, Xie N, Chen J, Yang N, … MacDonell KK (2014). Application of the protection motivation theory in predicting cigarette smoking among adolescents in China. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Chen X, & Wang Y (2018). Dynamic transitions between marijuana use and cigarette smoking among US adolescents and emerging adults. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2018.1434535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeman EC (1976). Catastrophe theory. Scientific American, 234(4), 65–83. [Google Scholar]