Abstract

Purpose

Patient preference is an essential component of patient-centered supportive cancer care; however, little is known about the factors that shape preference for treatment. This study sought to understand what factors may contribute to patient preference for two non-pharmacological interventions, acupuncture or cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).

Methods

We conducted individual, open-ended, semi-structured interviews among cancer survivors who had completed active treatment and met the diagnostic criteria for insomnia disorder. Two forms of codes were used for analysis: a priori set of codes derived from the key ideas and a set of codes that emerged from the data.

Results

Among 53 participants, the median age was 60.7 (range 27–83), 30 participants (56.6%) were female, and 18 (34%) were non-white. We identified three themes that contributed to an individual’s treatment preference: perception of the treatment’s evidence base, experience with the treatment, and consideration of personal factors. Participants gave preference to the treatment perceived as having stronger evidence. Participants also reflected on positive or negative experiences with both of the interventions, counting their own experiences, as well as those of trusted sources. Lastly, participants considered their own unique circumstances and factors such as the amount of work involved, fit with personality, or fit with their “type” of insomnia.

Conclusions

Knowledge of the evidence base, past experience, and personal factors shaped patient preference regardless of whether they accurately represent the evidence. Acknowledging these salient factors may help inform patient-centered decision-making and care.

Keywords: Insomnia, Cancer, Treatment preference, Acupuncture, Cognitive behavior therapy, Qualitative research methods

Background

The prevalence of insomnia in individuals with cancer is 30–60% compared to roughly 10% in the general population [1, 2]. Insomnia also frequently co-occurs with other commonly reported cancer side effects, such as pain, fatigue, psychological distress, and depression [3–6]. The inability to achieve restorative sleep has the potential to increase depressive symptomatology [7,8], decrease overall perception of quality of life [9, 10], and potentially translate into worse physical outcomes and survival [11, 12]. At present, the treatment of sleep difficulties in cancer patients is typically pharmacological [13]; however, these medications are not recommended for use longer than 4–5 weeks and are associated with a number of undesirable side effects, such as continued sleep difficulty and performance problems, memory disturbances, driving accidents, and falls [14, 15]. As a result, patients are increasingly turning to non-pharmacological and/or integrative therapies to manage their insomnia and comorbid symptoms in cancer.

Patient values and preferences have been largely overlooked as important factors influencing outcomes of non-pharmacological and integrative therapies. The term “preference” refers to the person’s favored treatment option, accounting for their informed attitudes about the relative desirability or undesirability of the characteristics of that treatment [16]. Desire for a specific treatment may prevent individuals with a strong preference from enrolling in trials or initiating treatment, increase attrition in patients not assigned to their preferred treatment, and decrease adherence to recommendations, all of which produce less than optimal treatment results [17].

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) and acupuncture are both commonly used as non-pharmacological treatments for insomnia and other comorbid symptoms [18–20], but little is known about what factors influence patient preference and choice of treatment. A recent meta-analysis established that CBT-I is associated with statistically and clinically significant improvement in sleep quality in cancer survivors [20]. Despite the evidence that CBT-I is a safe, effective, and durable intervention, up to 40% of patients terminate prematurely, and a significant proportion do not adequately adhere to treatment recommendations [21, 22]. While the reasons for termination of, or suboptimal response to, CBT-I are not fully understood, there is reason to believe that individual factors, such as preference, may influence treatment outcome. Estimates suggest that up to one third of cancer patients use acupuncture to help manage cancer-related symptoms [23]. While the evidence for the use of insomnia and comorbid symptoms is compelling [24–27], acupuncture research has also been criticized for having significant methodological limitation,s such as small sample size, questionable randomization, poor reporting, and inappropriate analyses [28–30].

Despite being used for the same condition, CBT-I and acupuncture have different key characteristics and behavioral requirements that potentially make them more or less appropriate and/or appealing to certain individuals. The objective of this study was to explore factors that influence treatment preference for insomnia. Understanding and addressing these factors in a clinical context may lead to more shared decision-making, contribute to patient-centered care, and improve overall outcomes.

Methods

Participants

We recruited a sample of 63 patients who consented to enroll in a comparative effectiveness trial of CBT-I vs. acupuncture [Clinical trial registration: NCT02356575] [31]. Preference was assessed using the Treatment Acceptability and Preference (TAP) measure [32]. The TAP instrument was used to provide participants with equivalent information about the nature of each of the treatments, the treatment schedule, the effectiveness and benefits, and the respective risks and potential side effects. The TAP measure contains three parts: a description of each treatment options, specific items assessing perception of the acceptability of each option, and two final questions inquiring about participants’ choice. The items are presented immediately following the treatment description and include: (a) appropriateness (i.e., the treatment option seems logical for addressing insomnia), (b) suitability to individual lifestyle, (c) effectiveness in managing insomnia, and (d) convenience, operationalized as willingness to apply and adhere to the treatment. Participants are asked to rate the treatment on the four attributes on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Finally, the participants are asked to indicate whether they had a preference or not, and if so, which treatment they preferred. The treatment descriptions used in this study are included in Supplement 1.

Nine participants stated no preference and one reported conflicting preference between the questionnaire and interview; these participants were omitted from this analysis for a total of 53 participants included. Qualitative interviews took place after completing the TAP measure, but prior to participants’ randomization into one of the two treatment arms. We included all interested English-speaking individuals over the age of 18 years with an unrestricted cancer diagnosis. Participants were required to have completed active treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) at least 1 month prior to study initiation. Participants were required to have a score > 7 on the Insomnia Severity Index and meet the criteria for insomnia disorder as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) as determined by clinical interview. Patients were screened for the following exclusionary conditions: the presence of another sleep disorder not adequately treated, previous experience with CBT or acupuncture for insomnia, the presence of an unstable psychological disorder, and employment in a job requiring shift work.

Procedure

Open-ended, semi-structured interviews were conducted to elicit participants’ experiences with sleep problems during and after their cancer treatment. A copy of the interview guide is included in Supplement 2. A trained research assistant (RA) conducted the interviews, with support from personnel at the Mixed Methods Research Lab at the University of Pennsylvania. At the completion of each interview, the RA dictated field notes about their impressions during the interview as well as interview circumstances that may have affected the data that were recorded. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, de-identified, and entered into an NVivo 11 database for coding and analysis.

Analysis

We used an integrated approach to the analysis of the data [33]. Two forms of codes were used: an a priori set of codes derived from the key ideas we sought to understand (e.g., factors that contributed to preference) and a set of codes that emerged from the data themselves. A data dictionary was developed that included all codes, their definitions, and decision rules for applying the code. Every fifth transcript was double coded and we used the interrater reliability function in NVivo to ascertain agreement between coders. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Results

Demographic characteristics

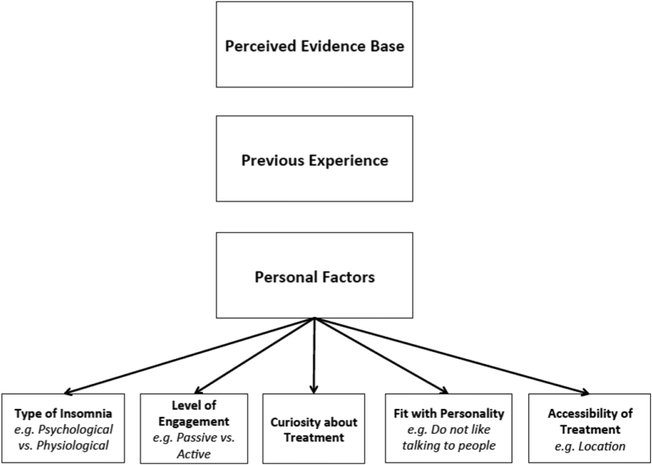

Of the 53 participants interviewed, 21 stated a preference for CBT-I compared to 32 reporting a preference for acupuncture. Please refer to Table 1 for a demographic breakdown by group. The mean age of the participants was 60.7 (SD = 12.8, range 27.5 to 83.6). The sample was comprised of 23 males (43.4%) and 30 females (56.6%). Eighteen individuals described themselves as non-white (34.0%). The factors that influenced patient preference for integrative insomnia therapies are summarized in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Preferred treatment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| CBT-I (n = 21) |

Acupuncture (n = 32) |

Full sample (N = 53) |

|

| Age (M ± SD) | 62.5 ± 11.3 N (%) |

59.4 ± 13.6 N (%) |

60.7 ± 12.8 N (%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 11 (52) | 12 (38) | 23 (43) |

| Female | 10 (48) | 20 (62) | 30 (57) |

| Race | |||

| White | 13 (62) | 22 (69) | 35 (66) |

| Non-white | 8 (38) | 10 (31) | 18 (34) |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 0 (0) | 4 (12) | 4 (8) |

| College or above | 21 (100) | 28 (88) | 49 (92) |

| Marital status | |||

| Not married | 10 (48) | 15 (47) | 25 (47) |

| Married/cohabitating | 11 (52) | 17 (53) | 28 (53) |

| Cancer type | |||

| Breast | 7 (33) | 9 (28) | 16 (30) |

| Prostate | 4 (19) | 5 (16) | 9 (17) |

| Colon/rectal | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Head/neck | 1 (5) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) |

| Hematological | 2 (9) | 4 (12) | 6 (11) |

| Gynecological | 1 (5) | 2 (6) | 3 (6) |

| Other cancer* | 4 (19) | 6 (19) | 10 (19) |

| More than 1 cancer | 1 (5) | 5 (16) | 6 (11) |

| Cancer stage | |||

| Stage 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Stage I | 12 (57) | 12 (38) | 24 (45) |

| Stage II | 2 (9) | 10 (31) | 12 (23) |

| Stage III | 4 (19) | 2 (6) | 6 (11) |

| Stage IV | 2 (9) | 5 (16) | 7 (13) |

| Unknown | 1 (5) | 2 (6) | 3 (6) |

Other cancer includes skin, lung, other gastrointestinal, other genitourinary, etc.

Fig. 1.

Factors influencing patient preference for integrative insomnia therapies

Perceived evidence base

Participants’ preferences for a specific treatment were influenced by its perceived evidence base. Those participants preferring acupuncture held the belief that acupuncture’s long history of use in eastern cultures conveyed effectiveness and value in the treatment, and the use of acupuncture to successfully treat other ailments, such as pain, injuries, and anxiety, supported participants’ beliefs in its ability to successfully treat insomnia. Similarly, participants reporting a preference for CBT-I felt the therapeutic practices underlying the treatment have a strong evidence base, stating that it was scientifically-driven, logical, and appropriate for the treatment of insomnia. Interestingly, though CBT-I is the “Gold Standard” non-pharmaceutical treatment for insomnia [15, 20, 34, 35], fewer participants expressed a belief in a strong evidence base for CBT-I compared to acupuncture.

Acupuncture

“I think that acupuncture’s history with healing is so well established in so many areas, and I don’t – I haven’t read a lot about it, but redirecting things within the body seems like – I’m sure insomnia has some biological basis, and so that seems perfectly acceptable that it would be able to treat insomnia.” – Female, 68, Head & Neck Cancer

CBT-I

“I guess I just understand it a little bit more – or I think I understand it a little bit more. I mean, it's – from what I understand, it's changing your behavior and building behavioral – or giving you techniques to try to false lead them to – and ways to – it used to be time management and all that kind of stuff that we used to do in business. “ – Male, 56, Colorectal Cancer

Conversely, those participants who shared a lack of knowledge surrounding the evidence base of either treatment typically expressed a preference for the treatment they were more familiar with. Some shared skepticism of acupuncture, stating that they did not have much experience with it or understand how it worked. For others, CBT-I was viewed as unfamiliar or less efficacious than acupuncture. Many had no prior experience or knowledge of CBT-I and were unclear as to how it could be beneficial to them.

Acupuncture

“Because I don't really know that much about either one. I just think that acupuncture is more – I imagine it's more effective than the other thing, but I don't really know what the other thing is.” – Male, 65, Prostate Cancer

CBT-I

“Whereas the acupuncture, I just don’t have as much knowledge in terms of its scientific basis. I don’t particularly understand how it works.” – Male, 46, Pancreatic Cancer

Previous experience

Patient preferences were also influenced by prior experience with the treatment, whether that experience was personal or came from a trusted source of information, such as family, friends, and care provider. A higher proportion of participants shared having had previous experience receiving acupuncture compared to those sharing a previous experience with therapy or counseling. Most participants had encountered acupuncture in the treatment of ailments such as pain or injury, but also for weight loss, smoking cessation, and overactive bladder,; whereas participants generally shared second-hand experiences of psychological treatment broadly, knowing family and friends who had experience or worked in the field.

Acupuncture

“I think more so it’s just how I know that my body reacted to it [acupuncture] from the past experience. Like I said, I’m pretty open to anything right now that would make me feel better as a whole, but I just know that – I was surprised because I'm very skeptical. And when I did it the first time, I was surprised how much better I actually – that’s the only time I think I've ever felt relaxed.” – Female, 34, Cervical Cancer

CBT-I

“I'm very curious about the cognitive behavior therapy because I never tried it. But, I’ve heard about it in the context of alcoholism and through an old, old friend of mine who’s been very active in AA.” - Male, 73, Skin Cancer

Those participants that had less favorable experiences or outcomes with a treatment typically shared less enthusiasm for that treatment and often stated a preference for the other option. For acupuncture, lack of success in previous treatment left them feeling uncertain of its use and effectiveness to treat insomnia. Those that had ineffective or negative previous experiences with CBT or other forms of counseling or therapy had a definite preference for acupuncture, often sharing that they would prefer an unknown treatment over a known, but ineffective treatment.

Acupuncture

“I’ve tried acupuncture twice without success, for other things. […] Once was for smoking cessation, and it didn’t work at all. And once was for pain in my shoulders, and it also didn’t work at all.” – Male, 67, Esophageal Cancer

CBT-I

“Honestly, talk therapy doesn't work – not for me. I've tried the getting in the bed, laying down, don't turn on the television, don't play the game on the phone, staying downstairs until I'm tired. I do all those things. I still have insomnia. So I don't feel like the talk therapy helps with insomnia for me as an individual, so I need to try something else that may work.” – Female, 45, Breast Cancer

Personal factors

Lastly, patients considered their own unique characteristics or situation, personality, and type of insomnia in deciding which treatment would provide the best outcome or meet their specific needs.

Type of insomnia

Participants spoke of one treatment option being ideal for their “type” of insomnia. This appeared to be driven by participant perceptions that physiological versus psychological factors were central or critically relevant to their insomnia, with physiological factors associated with a preference for acupuncture and psychological factors associated with a preference for CBT-I.

Acupuncture

“I just don’t think that that’s really what I – my issues are not behavioral. I don’t think anything’s changed. I don’t know how I – a lot of people are – and I’m not in denial about my treatment or my diagnosis or my prognosis. But I’m not depressed or concerned about it […] So I don’t – and I don’t – and there’s just things that I don’t – I could be wrong. I am skeptical that my behavior needs any kind of modification to improve. I could be proven wrong. But I would be highly skeptical of that prospect. If that makes sense.” – Male, 63, Neuroendocrine Cancer

CBT-I

“But I’m a worrier and I tend to – I guess one of the reasons why I said I had a preference for the cognitive therapy, which I saw on your survey, but which I suspected from before was when they talked about do racing thoughts go through your mind when you’re trying to sleep and that kind of thing. And that does happen with me. But it varies.” – Female, 78, Breast

Level of engagement

Participants viewed acupuncture and CBT-I as necessitating drastically different levels of engagement by the participant, with CBT-I being perceived as requiring significant participant engagement and acupuncture being perceived as more passive. Others felt that level of engagement with CBT-I reflected a more personal, tailored treatment that would best meet their needs and treat their insomnia.

Acupuncture

“Acupuncture is something that – you have to go to the appointments and they do it. But the other, it’s like, you actually have to do the work yourself. It’s like, okay, it’s like, I’m lazy. I hadn’t thought about that until I was reading through, and I thought, okay, that’s probably why you really prefer the one over the other.” – Female, 72, Breast Cancer

CBT-I

“I’m uncertain how lying on a bed or lying on a couch with needles in me is gonna be able to address insomnia. Because if I’m lying there, I’m not able to talk. I’m not able to say anything. I may be able to relax for about a good 30, 45 minutes, depending on how long the needles are in me. But I’m not gonna be able to discuss how I’m feeling. So I would rather be in a position whereas I’m able to talk about how I’m feeling and get some sort of feedback versus lying on the bed or on a couch or on a chair even with needles stuck in me and just lying there and that’s it. “ – Male, 48, Prostate Cancer

Curiosity

Some participants shared curiosity or interest for a treatment as being the driving factor behind their preference. Participants who voiced this perspective universally preferred acupuncture.

“And I would like to give myself the opportunity to see if [acupuncture] works, because I do – I have wanted to try it. I do believe that our bodies are a collection of different energies down to the chemical and molecular level, but then also just spiritually. So I think that it would be an interesting approach to access your Qi from a restfulness.” – Female, 40, Lung Cancer

Fit with personality

Some participants shared feeling that CBT-I might not be the right fit for their personality; these participants viewed themselves as proud, not talkative, or happy with their sleep schedule and that these traits inherently conflicted with the central tenants of CBT-I.

“Not really a big – I don’t know how you would put this – chatter. So I don’t think though sitting there talking to somebody about my daily life is going to help me any.” – Female, 45, Lymphoma

Accessibility of treatment

Accessibility was another factor that appeared to significantly influence patients’ treatment preference. Accessibility was conceptualized in both physical location of the two treatment options, and which option could be financially feasible to continue after the study had completed.

“It’s strictly economic. It’s strictly an economic decision. I suspect, I mean, it’s one of the benefits of Medicare is that I can get counseling for free, pretty much. I can get CBT relatively cheap. I have two counselors I use right now. Acupuncture is not gonna be that easy to find, number one. Then somebody who’s gonna be able to do it properly – to handle my particular set of problems, number two – would be problematic. Number three, the cost would probably be – long-term as a treatment strategy, would probably be more prohibitive.” – Male, 58, Leukemia

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the factors that influence treatment preference for integrative therapies for insomnia in cancer patients. Patients’ perception of evidence for acupuncture or CBT-I, experience with either treatment, and several personal factors, such as curiosity or a believed “match or fit” with a treatment, were offered as explanations for these preferences. There is a growing body of literature assessing patient preference for treatment, both conventional and complementary; however, few other studies have examined what factors influence treatment preferences within oncology generally and none have examined preferences for supportive or complementary therapies. In a qualitative study with 20 men with newly diagnosed, localized prostate cancer, treatment preferences were influenced by fear, uncertainty, misconceptions the men had about the various treatments, and the anecdotes of others [36]. This is similar to our findings, where preferences were highly polarized and largely based on the experience of trusted others. As we reveal, informed decision-making is often sidetracked by inaccurate information (e.g., acupuncture has a stronger evidence base), misconceptions (e.g., insomnia is either psychological or physiological), and factors unrelated to the treatments themselves (e.g., one treatment is easier to access).

Understanding what factors influence preference is important in the context of assisting patients make appropriate decisions with regards to their treatment. In a randomized controlled trial comparing standard patient education with or without preference measurement in 122 men with prostate cancer, those patients who underwent preference assessment were more certain about their treatment decisions and reported decreased levels of decisional conflict [37]. Similar benefits of shared decision-making have been reported for lung cancer [38] and breast cancer [39]. Despite the benefits of informed decision-making, evidence also suggests that physicians may be selective in when or how patient preference for treatment is taken into account [40], or whether patient preference is considered at all [41]. Inclusion of preference into patient-provider conversations and increasing awareness of the factors that shape patient preference for treatment may help correct misunderstandings or inaccurate beliefs about treatment.

In addition to aiding patients with treatment decisions, understanding patient preferences may lead to improved clinical outcomes. A multi-site randomized control trial with 271 participants diagnosed with stage I–III breast cancer showed that matching patients with preferred treatment translated into improved assessments of stress and quality of life [42]. Shingler et al. place treatment preference at the core of their theoretical model of determinants of clinical outcomes and adverse events. They identified that patient beliefs and values are both strongly influenced by, as well as impact, overall quality of life and success of treatment. Patients with strong preferences tend to exhibit better adherence, which could lead to better treatment outcomes. Fewer adverse events are reported in patients with strong beliefs in their treatment modality [43].

Providing treatment options, including open schedules, venues, and provider gender as well as modalities, have been found to impact treatment outcomes and perception of treatment success. In a survey of 14,587 patients receiving psychological treatments, those who had unmet preferences expressed significantly reduced benefit from treatment, whereas the greatest effect was seen in patients who were able to receive a preferred treatment modality [40]. These findings suggest that providing information and choices for treatment could provide better clinical outcomes, as well as higher patient satisfaction, while strengthening the patient-provider relationship [42].

Despite several strengths, including study size and participant diversity in terms of age, gender, and tumor type, there are a number of limitations, which must be noted. First, the interviews are necessarily based upon participants’ beliefs and experiences, which may be biased by the individual or interpreted incorrectly by the researcher. We made efforts to reduce the influence of the personnel responsible for data collection ; a senior researcher was consulted, and codes and extracted themes were validated with a subset of participants. Quotes were provided according to each topic to clearly convey the concepts identified with our interpretations. Second, participants recruited for the study may tend to have greater interest in insomnia treatments, particularly non-pharmacological options. Patients not willing to be randomized to an undesired treatment may not have consented to participate. As such, our findings may not generalize to those individuals with exclusive treatment preferences.

The results demonstrate that understanding and experience with a treatment option, as well as the patient's perception of treatment fit, significantlty shape preference. Informed decision-making requires that both physicians and patients are informed about the evidence for available treatments. Informed decision-making requires more than just providing the patient with information and asking them to describe their preference. Patients should be encouraged to describe the factors behind their preference so that this information can be corrected if necessary and factored into the treatment recommendation. For individuals with no or limited experience with the treatment, exposure and education may allow the patients to form a more accurate personal understanding of the intervention, reducing their likelihood of relying on the anecdotes of others. Ultimately, understanding factors that influence motivations for treatment in the context of integrative oncology care can help providers support their patients make informed treatment decisions and improve satisfaction and outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this article was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CER-1403-14292). This manuscript is also supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center (P30 CA008748). The statements presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. Sincere thanks go to the CHOICE Study Patient Advisory Board members (Bill Barbour, Winifred Chain, Linda Geiger, Donna-Lee Lista, Jodi MacLeod, Alice McAllister, Hilma Maitland, and Edward Wolff), the participants, and clinical staff for their support of this study.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest This research was supported by the sources acknowledged above. The funders had no part in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. The corresponding author has full control of all primary data and we agree to allow the journal to review this data if requested.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4086-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, Roth T, Savard J, Ancoli-Israel S, Heckler C, Purnell JQ, Janelsins MC, Morrow GR (2010) Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol 28(2):292–298. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savard J, Ivers H, Villa J, Caplette-Gingras A, Morin CM (2011) Natural course of insomnia comorbid with cancer: an 18-month longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol 29(26):3580–3586. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fiorentino L, Rissling M, Liu L, Ancoli-Israel S (2011) The symptom cluster of sleep, fatigue and depressive symptoms in breast cancer patients: severity of the problem and treatment options. Drug Discov Today Dis Models 8(4):167–173. 10.1016/j.ddmod.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bower JE (2008) Behavioral symptoms in patients with breast cancer and survivors. J Clin Oncol 26(5):768–777. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Kwan L, Breen EC, Cole SW (2011) Inflammation and behavioral symptoms after breast cancer treatment: do fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance share a common underlying mechanism? J Clin Oncol 29(26):3517–3522. 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Onselen C, Cooper BA, Lee K, Dunn L, Aouizerat BE, West C, Dodd M, Paul S, Miaskowski C (2012) Identification of distinct subgroups of breast cancer patients based on self-reported changes in sleep disturbance. Support Care Cancer 20(10):2611–2619. 10.1007/s00520-012-1381-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colagiuri B, Christensen S, Jensen AB, Price MA, Butow PN, Zachariae R (2011) Prevalence and predictors of sleep difficulty in a national cohort of women with primary breast cancer three to four months postsurgery. J Pain Symptom Manag 42(5):710–720. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franzen PL, Buysse DJ (2008) Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 10(4):473–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Fiorentino L, Rissling M, Natarajan L, Parker BA, Dimsdale JE, Mills PJ, Sadler GR, Ancoli-Israel S (2013) Decreased health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer is associated with poor sleep. Behav Sleep Med 11(3):189–206. 10.1080/15402002.2012.660589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grutsch JF, Ferrans C, Wood PA, Du-Quiton J, Quiton DF, Reynolds JL, Ansell CM, Oh EY, Daehler MA, Levin RD, Braun DP, Gupta D, Lis CG, Hrushesky WJ (2011) The association of quality of life with potentially remediable disruptions of circadian sleep/activity rhythms in patients with advanced lung cancer. BMC Cancer 11(1):193 10.1186/1471-2407-11-193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mormont MC, Waterhouse J (2002) Contribution of the rest-activity circadian rhythm to quality of life in cancer patients. Chronobiol Int 19(1):313–323. 10.1081/CBI-120002606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mormont MC, Waterhouse J, Bleuzen P, Giacchetti S, Jami A, Bogdan A, Lellouch J, Misset JL, Touitou Y, Levi F (2000) Marked 24-h rest/activity rhythms are associated with better quality of life, better response, and longer survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and good performance status. Clin Cancer Res 6(8):3038–3045 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore TA, Berger AM, Dizona P (2011) Sleep aid use during and following breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Psychooncology 20(3):321–325. 10.1002/pon.1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kripke DF (2006) Risks of chronic hypnotic use In: Lader M, Cardinali DP, Pandi-Perumal SR (eds) Sleep and sleep disorders: a neuropsychopharmacological approach. Springer Science, Berlin, pp 141–145. 10.1007/0-387-27682-3_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians (2016) Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 165(2):125–133. 10.7326/M15-2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llewellyn CD, Horney DJ, McGurk M, Weinman J, Herold J, Altman K, Smith HE (2011) Assessing the psychological predictors of benefit finding in patients with head and neck cancer. Psychooncology 22:97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preference Collaborative Review Group (2008) Patients’ preferences within randomised trials: systematic review and patient level meta-analysis. BMJ 337(oct31 1):a1864 10.1136/bmj.a1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi TY, Kim JI, Lim HJ, Lee MS (2017) Acupuncture for managing cancer-related insomnia: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Integr Cancer Ther 16(2):135–146. 10.1177/1534735416664172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun H, Sun L, Mao JJ (2017) Growth of integrative medicine at leading cancer centers between 2009 and 2016: a systematic analysis of NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center websites. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2017(52). 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgx004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JA, Rash JA, Campbell TS, Savard J, Gehrman PR, Perlis M, Carlson LE, Garland SN (2015) A systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) in cancer survivors. Sleep Med Rev 27:20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews EE, Arnedt JT, McCarthy MS, Cuddihy LJ, Aloia MS (2013) Adherence to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 17(6):453–464. 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ong JC, Kuo TF, Manber R (2008) Who is at risk for dropout from group cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia? J Psychosom Res 64(4):419–425. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu W, Dean-Clower E, Doherty-Gilman A, Rosenthal DS (2008) The value of acupuncture in cancer care. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 22(4):631–648, viii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao K (2013) Acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia. Int Rev Neurobiol 111:217–234. 10.1016/B978-0-12-411545-3.00011-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeung WF, Chung KF, Zhang SP, Yap TG, Law AC (2009) Electroacupuncture for primary insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep 32(8):1039–1047. 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeung WF, Chung KF, Leung YK, Zhang SP, Law AC (2009) Traditional needle acupuncture treatment for insomnia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med 10(7):694–704. 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruan JW, Wang CH, Liao XX, Yan YS, Hu YH, Rao ZD, Wen M, Zeng XX, Lai XS (2009) Electroacupuncture treatment of chronic insomniacs. Chin Med J 122(23):2869–2873 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheuk DK, Yeung WF, Chung KF, Wong V (2012) Acupuncture for insomnia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9:CD005472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ernst E, Lee MS, Choi TY (2011) Acupuncture for insomnia? An overview of systematic reviews. Eur J Gen Pract 17(2):116–123. 10.3109/13814788.2011.568475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao H, Pan X, Li H, Liu J (2009) Acupuncture for treatment of insomnia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med 15(11):1171–1186. 10.1089/acm.2009.0041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garland SN, Gehrman P, Barg FK, Xie SX, Mao JJ (2016) CHoosing Options for Insomnia in Cancer Effectively (CHOICE): design of a patient centered comparative effectiveness trial of acupuncture and cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia. Contemp Clin Trials 47:349–355. 10.1016/j.cct.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sidani S, Epstein DR, Bootzin RR, Moritz P, Miranda J (2009) Assessment of preferences for treatment: validation of a measure. Res Nurs Health 32(4):419–431. 10.1002/nur.20329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH (2009) Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 119(10):1442–1452. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, Friedman L, Boehlecke B, Brown T, Coleman J, Kapur V, Lee-Chiong T, Owens J, Pancer J, Swick T, American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2006) Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep 29(11):1415–1419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger AM, Matthews EE, Kenkel AM (2017) Management of sleep-wake disturbances comorbid with cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 31(8):610–617 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Steiner JF (2006) Patient treatment preferences in localized prostate carcinoma: the influence of emotion, misconception, and anecdote. Cancer 107(3):620–630. 10.1002/cncr.22033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shirk JD, Crespi CM, Saucedo JD, Lambrechts S, Dahan E, Kaplan R, Saigal C (2017) Does patient preference measurement in decision aids improve decisional conflict? A randomized trial in men with prostate cancer. Patient. 10.1007/s40271-017-0255-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt K, Damm K, Prenzler A, Golpon H, Welte T (2016) Preferences of lung cancer patients for treatment and decision-making: a systematic literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 25(4):580–591. 10.1111/ecc.12425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamelinck VC, Bastiaannet E, Pieterse AH, Jannink I, van de Velde CJ, Liefers GJ, Stiggelbout AM (2014) Patients’ preferences for surgical and adjuvant systemic treatment in early breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 40(8):1005–1018. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams R, Farquharson L, Palmer L, Bassett P, Clarke J, Clark DM, Crawford MJ (2016) Patient preference in psychological treatment and associations with self-reported outcome: national cross-sectional survey in England and Wales. BMC Psychiatry 16(1):4 10.1186/s12888-015-0702-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scherr KA, Fagerlin A, Hofer T, Scherer LD, Holmes-Rovner M, Williamson LD, Kahn VC, Montgomery JS, Greene KL, Zhang B, Ubel PA (2017) Physician recommendations trump patient preferences in prostate cancer treatment decisions. Med Decis Mak 37(1):56–69. 10.1177/0272989X16662841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carlson LE, Tamagawa R, Stephen J, Doll R, Faris P, Dirkse D, Speca M (2014) Tailoring mind-body therapies to individual needs: patients’ program preference and psychological traits as moderators of the effects of mindfulness-based cancer recovery and supportive-expressive therapy in distressed breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2014(50):308–314. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shingler SL, Bennett BM, Cramer JA, Towse A, Twelves C, Lloyd AJ (2014) Treatment preference, adherence and outcomes in patients with cancer: literature review and development of a theoretical model. Curr Med Res Opin 30(11):2329–2341. 10.1185/03007995.2014.952715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.