Abstract

Background

Sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) is distinct from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder inattention (ADHD-IN) and concurrently associated with a range of impairment domains. However, few longitudinal studies have examined SCT as a longitudinal predictor of adjustment. Studies to date have all used a relatively short longitudinal time-span (six months to two years) and only rating scale measures of adjustment. Using a prospective, multi-method design, this study examined whether SCT and ADHD-IN were differentially associated with functioning over a ten-year period between preschool and the end of ninth grade.

Methods

Latent state-trait modeling determined the trait variance (i.e., consistency across occasions) of SCT and ADHD-IN across four measurement points (preschool and the end of kindergarten, first grade, and second grade) in a large population-based longitudinal sample (N=976). Regression analyses were used to examine trait SCT and ADHD-IN factors in early childhood as predictors of functioning at the end of ninth grade (i.e., parent ratings of psychopathology and social/academic functioning, reading and mathematics academic achievement scores, processing speed and working memory).

Results

Both SCT and ADHD-IN contained more trait variance (Ms = 65% and 61%, respectively) than occasion-specific variance (Ms = 35% and 39%) in early childhood, with trait variance increasing as children progressed from preschool through early elementary school. In regression analyses: (1) SCT significantly predicted greater withdrawal and anxiety/depression whereas ADHD-IN did not uniquely predict these internalizing domains; (2) ADHD-IN uniquely predicted more externalizing behaviors whereas SCT uniquely predicted fewer externalizing behaviors; (3) SCT uniquely predicted shyness whereas both SCT and ADHD-IN uniquely predicted global social difficulties; and (4) ADHD-IN uniquely predicted poorer math achievement and slower processing speed whereas SCT more consistently predicted poorer reading achievement.

Conclusions

Findings of the current study – from the longest prospective sample to date – provide the clearest evidence yet that SCT and ADHD-IN often differ when it comes to the functional outcomes they predict.

Keywords: academic achievement, ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbidity, processing speed, sluggish cognitive tempo, working memory

Introduction

Studies on sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) in children have demonstrated that SCT is (1) internally consistent, generally stable over time, and likely heritable, (2) empirically distinct from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other psychopathologies, and (3) associated with poorer functioning across a number of adjustment domains (Barkley, 2014; Becker et al., 2016). These findings raise the possibility that SCT may be its own psychiatric disorder (Barkley, 2014) or a construct of transdiagnostic importance (Becker et al., 2016; Becker & Willcutt, 2018).

SCT is currently defined by behavioral symptoms reflecting both slowness/drowsiness (e.g., sluggishness, appearing sleepy) and inconsistent alertness/mental confusion (e.g., daydreaming, seeming to be in a fog). Although SCT and ADHD inattentive (ADHD-IN) symptoms are empirically distinct, they are strongly correlated (r=0.63) in childhood (Becker et al., 2016). Both SCT and ADHD-IN are conceptualized as reflecting difficulties in attention regulation, though perhaps with different etiologies in attentional brain systems (Barkley, 2014; Becker & Willcutt, 2018). For example, it has been hypothesized that SCT may in part derive from poor efficiency in the orienting network (Becker & Willcutt, 2018), and a recent neuroimaging study found SCT to be associated with hypoactivity in the superior parietal lobe consistent with this possibility (Fassbender et al., 2015). Still, given the strong associations between SCT and ADHD-IN and at times similar item content, researchers have questioned if SCT and ADHD-IN are theoretically or empirically distinct as well as associated with distinct functional outcomes.

SCT in relation to mental health, social, academic, and neuropsychological functioning

Research examining the clinical correlates of SCT have largely focused on whether SCT is associated with functioning above and beyond the contribution of ADHD-IN. These efforts have generally reported consistent findings linking SCT to increased internalizing symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, somatization) (Barkley, 2013; Becker et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2017; Penny et al., 2009) and social difficulties including social withdrawal/isolation specifically (Becker et al., 2017; Carlson & Mann, 2002; Marshall et al., 2014; Willcutt et al., 2014). In addition, SCT and ADHD-IN are differentially related to externalizing behaviors; whereas ADHD-IN symptoms are strongly, positively associated with externalizing behaviors (e.g., hyperactivity-impulsivity [ADHD-HI], oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], aggression), SCT is either unassociated with these behaviors or negatively associated with externalizing behaviors when controlling for ADHD-IN (Becker et al., 2016).

There is less clear evidence linking SCT to academic functioning. Some recent studies have found SCT symptoms to be associated with greater academic impairment ratings, above and beyond ADHD-IN symptoms (Khadka et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016; Smith & Langberg, 2017), though mixed findings have also been reported (Belmar et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2018). The evidence is also mixed among studies examining SCT in relation to academic achievement test performance. Some studies have found SCT to be unassociated with academic achievement when controlling for ADHD-IN (Becker & Langberg, 2013; Marshall et al., 2014). Others have found parent-rated SCT to be associated with reading achievement but not math achievement (Hartman et al., 2004; Tamm et al., 2016), math achievement but not reading (Bauermeister et al., 2012), or uniquely associated with both (Willcutt et al., 2014). These mixed findings underscore the need for additional research.

Findings for neuropsychological test performance are even less consistent, though few studies have examined both SCT and ADHD-IN as independent predictors of neuropsychological functioning. When SCT and ADHD-IN have been considered simultaneously, SCT is uniquely associated with poorer sustained attention, whereas ADHD-IN is uniquely associated with poorer working memory performance (Bauermeister et al., 2012; Tamm et al., 2018; Wåhlstedt & Bohlin, 2010; Willcutt et al., 2014). In some studies, both SCT and ADHD-IN are associated with slower processing speed (Tamm et al., 2018; Willcutt et al., 2014), whereas others have found that SCT is unassociated with processing speed above and beyond ADHD-IN symptoms (Bauermeister et al., 2012; Wood et al., 2017). Additional studies are needed to evaluate whether SCT is associated with neuropsychological test performance and processing speed specifically.

The need to differentiate SCT and ADHD-IN using longitudinal research

As research findings linking SCT to adjustment have accumulated, one key issue has remained largely unchanged: the need for longitudinal research (Becker, 2017). The vast majority of empirical findings are based on cross-sectional research. We are aware of only two samples that have examined SCT as a longitudinal predictor of adjustment (Becker, 2014; Bernad et al., 2016; Servera et al., 2016). In the first study, Becker (Becker, 2014) found SCT symptoms to predict increases in teacher-rated peer difficulties over the course of a single school year in a sample of 176 children. The other three longitudinal studies examining the predictive validity of SCT used the same sample of 758 Spanish children studied across one- and two-year longitudinal spans. Together, these studies generally found SCT symptoms to predict higher depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as increased social and academic impairment, independent of ADHD-IN. SCT symptoms were also either unassociated or associated with less ADHD-HI and ODD symptoms when controlling for ADHD-IN (Bernad et al., 2016; Servera et al., 2016).

Although these studies provide key initial evidence of SCT predicting later adjustment in children, they have all used a relatively short longitudinal time-span (i.e., six months to two years) and only rating scale measures of functioning. Studies examining the functional correlates of SCT over longer developmental periods are needed. Since SCT symptoms increase slightly from childhood to adolescence (Leopold et al., 2016), it is especially important to understand whether SCT symptoms in childhood also predict functioning during adolescent development. If SCT and ADHD-IN in childhood differentially predict functioning domains in adolescence, such findings would further advance the validity of the SCT construct and inform how distinct but closely related attentional problems may have different developmental outcomes. Research in this vein is important for advancing theory and, ultimately, clinical care. For instance, findings from longitudinal research linking SCT to greater internalizing psychopathology and less externalizing psychopathology would shed light on the hypothesis that SCT is best conceptualized as part of the internalizing rather than externalizing spectra of psychopathology, which itself is theoretically important and has implications for etiology, pathophysiology, developmental course, and treatment (Becker & Willcutt, 2018).

The current study

Using a prospective longitudinal, multi-method design, this study examined whether SCT symptoms were associated with functioning over a ten-year period between preschool and the end of ninth grade. Specifically, in a large sample representative of the State of Colorado (United States), parent report of SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms were collected when children were in preschool and again at the end of kindergarten, first grade, and second grade. These four assessments were used to determine the amount of trait and occasion-specific variance in the SCT and ADHD-IN symptom ratings in early childhood (Objective 1). Trait variance (i.e., consistency across occasions) reflects true score variance that is purely person-specific and independent of the occasion and/or person-occasion interaction while occasion-specific variance reflects true score variance that is specific to the occasion of measurement. We predicted that the SCT and ADHD-IN symptom ratings would contain more trait than occasion-specific variance (Preszler, Burns, Litson, Geiser, Servera, et al., 2017).

We then examined whether the SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors in early childhood were correlated with functioning assessed at the end of ninth grade (Objective 2). We examined functioning using parent ratings (i.e., internalizing symptoms, externalizing behaviors, social difficulties, reading/math skills), academic achievement test performance (i.e., reading achievement, mathematics achievement), and neuropsychological test performance (i.e., processing speed, working memory). Finally, regression analyses were conducted to examine whether the SCT trait factor in early childhood was independently associated with adolescent functioning above and beyond the ADHD-IN trait factor, and likewise, whether the ADHD-IN trait factor in early childhood was independently associated with adolescent functioning above and beyond the SCT trait factor (Objective 3). We hypothesized that trait SCT and ADHD-IN in early childhood would each be independently associated with adolescent functioning, but in different ways. We expected trait SCT in early childhood to uniquely predict greater internalizing symptoms and academic and social difficulties (Becker, 2014; Becker et al., 2016; Bernad et al., 2016; Willcutt et al., 2014). We also expected trait SCT in early childhood to be unassociated with or to predict lower externalizing behaviors in adolescence (Bernad et al., 2016; Carlson & Mann, 2002; Marshall et al., 2014). Given mixed findings in previous research, we tentatively hypothesized that trait SCT would uniquely predict lower reading and mathematics achievement scores, but would not uniquely predict processing speed or working memory test scores (Bauermeister et al., 2012; Hartman et al., 2004; Tamm et al., 2016; Willcutt et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2017). We expected trait ADHD-IN in early childhood to uniquely predict greater externalizing behaviors and academic and social difficulties, as well as lower achievement and neuropsychological test scores in adolescence (Bauermeister et al., 2012; Bernad et al., 2016; Willcutt et al., 2014). Finally, we expected trait ADHD-IN to be unassociated or weakly associated with internalizing symptoms when controlling for trait SCT (Becker et al., 2014; Bernad et al., 2016; Penny et al., 2009).

Methods

Participants

Participants were 976 individuals drawn from 224 monozygotic (i.e., identical) and 265 dizygotic (i.e., fraternal) twin pairs (50% female) with 965, 904, 884, 900, and 930 individuals at the pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, first grade, second grade, and ninth grade assessments, respectively. There were 12 pre-kindergarten children without SCT or ADHD-IN ratings at the pre-kindergarten timepoint, though these children could have SCT or ADHD-IN ratings at subsequent waves, resulting in a total of 976 unique children in the study. Thus, retention of the full sample at the ninth-grade assessment was 95%.

All participants were part of the Colorado component of the International Longitudinal Twin Study of Early Reading Development (ILTSERD; e.g., (Christopher et al., 2015). The Colorado twins were recruited from the Colorado Twin Registry, a registry based on birth records that includes information on over 90% of all twin births in Colorado. Comparisons with available normative data on several measures suggest that the current sample is representative of the overall population in the state (Christopher et al., 2015). Approximately 85% of mothers and 83% of fathers identified as White; most mothers (61%) and fathers (54%) completed 13–16 years of education See Table 1 for additional details regarding parental race/ethnicity, education level, and other sample characteristics.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| M ± SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Child Age (years) | ||

| Pre-kindergarten | 4.90 ± 0.19 | 4.5 – 5.9 |

| Kindergarten | 6.27 ± 0.31 | 5.5 – 7.1 |

| First grade | 7.42 ± 0.32 | 6.6 – 8.7 |

| Second grade | 8.45 ± 0.31 | 7.7 – 9.5 |

| Ninth grade | 15.46 ± 0.32 | 14.6 – 16.6 |

| Child IQ estimate (Pre-K) | ||

| WPPSI-R Vocabulary | 10.52 ± 3.08 | 1 – 19 |

| WPPSI-R Block Design | 10.30 ± 2.51 | 2 – 18 |

| N | % | |

|

|

||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 490 | 50.2 |

| Male | 486 | 49.8 |

| Second grade elevations in SCT and/or ADHD-INa | ||

| SCT (but not ADHD-IN) | 51 | 5.67 |

| ADHD-IN (but not SCT) | 25 | 2.78 |

| SCT + ADHD-IN | 17 | 1.89 |

| Mothers | Fathers | |

|

|

||

| Parent Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 84.9% | 82.8% |

| Black | 2.5% | 1.6% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1.6% | 0.8% |

| Hawaiian | 0.6% | 0.2% |

| Japanese | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Chinese | 0% | 0.4% |

| Filipino | 0% | 0.4% |

| Parent Highest Education Level | ||

| Fewer than 12 years | 1.8% | 2.3% |

| 12 years (completed high school) | 14.3% | 20.5% |

| 13–16 years | 61.3% | 53.7% |

| More than 16 years | 22.5% | 23.6% |

Note. N = 976. Parental race/ethnicity information was available for 830 mothers and 810 fathers. Parental education information was available for 976 mothers and 968 fathers.

a Elevations in sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) and/or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder inattention (ADHD-IN) symptoms, defined as >2 SD above the mean, are provided to further describe the sample based on the second grade timepoint since this timepoint is when SCT and ADHD-IN demonstrated the greatest trait variance.

Procedures

The twins were first assessed during the summer prior to starting kindergarten (Mage=4.9 years). After the initial preschool assessment, participants were assessed again in the summers following kindergarten (Mage=6.3 years), first grade (Mage=7.4 years), second grade (Mage=8.5 years), and ninth grade (Mage=15.5 years).

Overall testing procedures for the ILTSERD are described in detail elsewhere (e.g., (Christopher et al., 2015). Briefly, at each wave the twins completed a battery of measures in an individual testing session while one parent or caregiver completed a battery of questionnaires that included the measures described in this study. Testing was completed in a single session in the twins’ homes or at the University of Colorado Boulder. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants and their parents at initial enrollment and at each follow-up assessment.

Measures

A brief overview of measures is provided here, with a more thorough description of the measures provided in the online supporting information, including a table summarizing the psychometric properties of the measures at each assessment wave (Table S1).

ADHD and SCT

At each of the assessments the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale (DBRS; (Barkley & Murphy, 1998) was used to obtain parent ratings of 18 symptoms of ADHD and 9 symptoms of ODD. Nearly all ratings were completed by the mother at all time points (90–95%). On the DBRS, the parent is asked to indicate how often in the last 6 months each symptom occurred on a four-point scale (0=never or rarely, 1=sometimes, 2=often, and 3=very often). At each assessment seven potential SCT symptoms were rated by parents on the same scale as the DBRS. Five of these seven SCT symptoms showed convergent and discriminant validity with the ADHD-IN factor: (1) sluggish, slow to respond, (2) seems to be in a fog, (3) drowsy or sleepy, (4) easily confused, and (5) daydreams, stares into space. These five symptoms defined the SCT construct. Two of the SCT symptoms (seems not to hear; absented minded, forgets things) loaded equally on the SCT and ADHD-IN factors for each of the four occasions, thus failing to show discriminant validity. The five items used to define the SCT construct in this study demonstrate adequate internal consistency (αs = .70 - .77 across waves; see Table S1) and include some aspects of both slowness/drowsiness and inconsistent alertness that have been used to define SCT in previous studies (Barkley, 2013; Lee et al., 2014; McBurnett et al., 2014; Penny et al., 2009).

Other Symptom Dimensions

During the assessment at the end of ninth grade, parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The narrow-band scales used in the current study were Withdrawn, Anxiety/Depression, Somatic Complaints, Aggressive Behavior, and Delinquent Behavior.

Social Functioning

A parent rating of shyness was provided on the same scale as the DBRS described earlier. In addition, overall social difficulties were assessed by parent ratings on the Colorado Learning Difficulties Questionnaire (CLDQ; (Willcutt et al., 2011).

Academic Functioning

Parent ratings on the CLDQ (Willcutt et al., 2011) Reading and Math subscales were used as a measure of academic functioning at the end of ninth grade. Participants also completed a battery of standardized measures of reading and mathematics achievement. The Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement: Third Edition (WJ-III; (McGrew & Woodcock, 2001) includes reliable subtests that assess untimed single word reading (Word Identification), timed reading fluency (Reading Fluency), and reading comprehension (Passage Comprehension). The Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE; (Torgesen et al., 1999) measures fluent reading of single words. For math, the WJ-III includes an untimed paper-and-pencil measure of mathematics calculations (Calculations), a subtest that requires participants to complete math word problems that are presented orally by the examiner (Applied Problems), and a subtest that requires participants to complete as many simple arithmetic problems as possible within three minutes (Math Fluency).

Cognition

Three widely-used cognitive measures were administered at the end of ninth grade to assess working memory and processing speed, two cognitive domains that may be associated with SCT (Becker et al., 2016). The WISC-R Digit Span subtest (Wechsler, 1974) assesses short-term verbal and working memory, and the WISC-R Coding subtest (Wechsler, 1974) and WISC-III Symbol Search subtest (Wechsler, 1991) are paper-and-pencil measures of processing speed.

Analytic approach

Estimation, clustering, and model fit

The analyses used the Mplus statistical software (version 8.0) (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). All the analyses used the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) since the manifest variables were approximately continuous. Given the twins were nested within families (i.e., two twins per family), the Mplus type=complex option was used to correct the standard errors. The global fit of the latent state-trait (LST) model was evaluated with the comparative fit index (CFI; close fit ≥.95), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; close fit ≤.05), and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR; close fit ≤.05) (Little, 2013).

Objective 1: Trait and state variance in SCT and ADHD-IN symptom ratings

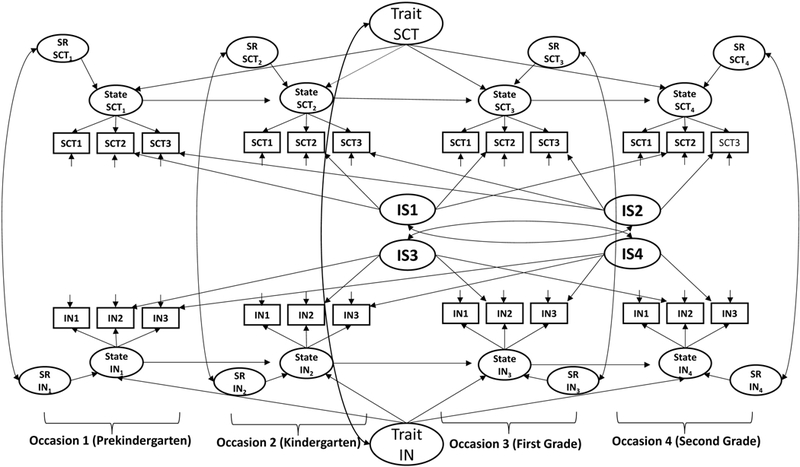

The first objective was to use a single source (mothers)—two construct (SCT and ADHD-IN) LST model to determine the amount of trait and occasion-specific variance in the SCT and ADHD-IN symptom ratings for the four occasions of measurement (i.e., pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, first grade, and second grade). The ADHD-IN state factor at each occasion of measurement was defined by three symptom parcels with three ADHD-IN symptoms in each parcel (i.e., each parcel contained the same three ADHD-IN symptoms at each of the four occasions). The SCT state factor at each occasion of measurement was also defined by two parcels and one indicator (i.e., two SCT symptoms in the first parcel, two SCT symptoms in the second parcel, and one SCT symptom in the third indicator). Little’s (Little, 2013) procedure to create homogenous parcels was used to assign items to the parcels (for justification on the use of parcels, see (Little et al., 2013). Figure 1 shows this LST model (see (Geiser et al., 2017), for a more detailed description of LST models).

Figure 1.

Single source-two construct (SCT and ADHD-IN) latent state-trait—autoregressive model. The supplementary materials show the Mplus code for the model. SCT = sluggish cognitive tempo; ADHD-IN = attention-deficit/hyperactivity-disorder – inattention; SR = state residual factor; IS = indicator (parcel) specific method factor. See Geiser et al. (2017) for additional information on latent state-trait models.

Objective 2: Early childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors as bivariate predictors of adolescent functioning

The childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors were correlated with the post ninth-grade measures of adolescent functioning (i.e., externalizing and internalizing symptom dimensions, social difficulties, parent perception of academic skills, reading achievement, mathematics achievement, processing speed and working memory). The analyses allowed us to determine the bivariate associations of childhood trait SCT and ADHD-IN with adolescent functioning.

Objective 3: Early childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors as unique predictors of adolescent functioning.

The childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors were used in regression analyses to predict the measures of adolescent functioning (i.e., the ninth-grade measures of adolescent functioning were regressed on childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors). These analyses allowed us to determine the unique ability of the childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors to predict adolescent functioning.

Results

Missing data

Participants with missing information on the 20 ninth grade measures were compared to participants with information on the 20 ninth grade measures on the ADHD-IN and SCT measures for the pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, first grade, and second grade assessments (i.e., 20 multivariate F-tests on the eight ADHD-IN and SCT measures). None of the 20 multivariate tests were significant (ps>.3). Covariance coverage varied from 85% to 99% for the LST trait model, indicating little missing information for the SCT and ADHD-IN symptom ratings for the first four years. For the regression models, covariance coverage varied from 79% to 98%. An examination of the patterns of missing information for the predictors and outcomes did not suggest any systematic reasons for missing information. The robust maximum likelihood estimator does not eliminate any data (Brown, 2015, chap. 9).

Latent State-Trait (LST) model

The LST model resulted in close fit, χ2(259)=345, p<.001, CFI=.990, RMSEA=.018 (.013, .023), and SRMR=.038. There was also no meaningful localized ill-fit in this model (e.g., for the 276 residuals in the residual covariance matrix there were none larger than .03 with most less than .01). The average amount of trait variance in the four SCT state factors (one at each of the four occasions of measurement, see Figure 1) was 65% (range: 48% to 79%). The average amount of trait variance in the four ADHD-IN state factors was 61% (range: 41% to 71%). The lowest amount of trait variance was for the pre-kindergarten state factor (i.e., 48% for SCT and 41% for ADHD-IN) with there being a significant (ps<.01) increase in trait variance for SCT and ADHD-IN symptom ratings as the children became older (i.e., significant autoregressive coefficients in the model).1 The correlation between the SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors was 0.66 (SE=.04), indicating moderate discriminant validity (i.e., only 44% of their true score variance was shared, which is considered good given both constructs represent attention problems). Given the close fit of this model and the substantial amount of trait variance in SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors (Objective 1), it was appropriate to determine the ability of the childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors to predict adolescent functioning.

Early childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors’ bivariate and unique relationships with adolescent functioning

Table 2 shows the correlations and partial standardized regression coefficients between the childhood SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors and the measures of adolescent functioning. With the exception of childhood trait SCT in relation to adolescent delinquency, both SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors in childhood were significantly correlated with adolescent functional outcomes. Our focus herein is on the unique effects of the SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors in relation to adolescent functioning.

Table 2.

Early Childhood Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and ADHD-Inattention Trait Factors’ Bivariate and Unique Relationships with Adolescent Functioning

| Bivariate Correlations | Regression Coefficients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCT | ADHD-IN | SCT | ADHD-IN | |||||

| Ninth Grade Measures | r | SE | r | SE | β | SE | β | SE |

| Externalizing Symptom Dimensions | ||||||||

| Aggressive Behavior | .11* | .04 | .32** | .06 | −.17* | .07 | .42** | .09 |

| Delinquent Behavior | .06ns | .05 | .24* | .07 | −.16* | .07 | .33** | .10 |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | .13* | .04 | .42** | .04 | −.27** | .07 | .59** | .07 |

| Oppositional Defiant | .17* | .04 | .38** | .05 | −.13* | .07 | .45** | .07 |

| Internalizing Symptom Dimensions | ||||||||

| Social Withdrawal | .29** | .06 | .26** | .05 | .20* | .08 | .12ns | .07 |

| Somatic Complaints | .14* | .05 | .14* | .06 | .08ns | .07 | .09ns | .08 |

| Anxiety/Depression | .23** | .05 | .21** | .05 | .17* | .08 | .09ns | .08 |

| Social Functioning Dimensions | ||||||||

| Shyness | .25** | .06 | .13* | .04 | .29** | .08 | −.06ns | .06 |

| CLDQ Social Difficulties | .35** | .05 | .39** | .04 | .19* | .08 | .24** | .07 |

| Parent Perception of Academic Impairment | ||||||||

| CLDQ Reading | .36** | .05 | .43** | .05 | .12ns | .08 | .35** | .07 |

| CLDQ Math | .33** | .05 | .37** | .04 | .15* | .08 | .26** | .07 |

| Reading Achievement | ||||||||

| WJ Reading fluency | −.30** | .04 | −.32** | .04 | −.16* | .06 | −.21* | .07 |

| WJ Word identification | −.21** | .05 | −.22** | .04 | −.17* | .07 | −.07ns | .07 |

| WJ Passage comprehension | −.22** | .04 | −.20** | .04 | −.20* | .07 | −.04ns | .07 |

| TOWRE Reading fluency | −.25** | .05 | −.25** | .04 | −.18* | .07 | −.11ns | .07 |

| Mathematics Achievement | ||||||||

| WJ Math fluency | −.25** | .05 | −.33** | .04 | −.05ns | .06 | −.28** | .06 |

| WJ Applied problems | −.18** | .05 | −.23** | .05 | −.08ns | .07 | −.16* | .06 |

| WJ Calculations | −.21** | .05 | −.24** | .04 | −.11ns | .07 | −.15* | .06 |

| Processing Speed and Working Memory | ||||||||

| WISC Coding | −.29** | .04 | −.36** | .04 | −.06ns | .06 | −.33** | .06 |

| WISC Symbol Search | −.24** | .05 | −.30** | .04 | −.05ns | .06 | −.27** | .06 |

| WISC Digit Span | −.16* | .05 | −.16* | .04 | −.10ns | .06 | −.09ns | .06 |

Note. SCT=sluggish cognitive tempo; ADHD-IN=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-inattention; WJ=Woodcock Johnson; CLDQ=Colorado Learning Difficulties Questionnaire. WISC=Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children.

p<.05

p<.001

Externalizing symptom dimensions

Higher scores on the ADHD-IN trait factor significantly predicted (ps<.001) higher scores on the aggression, delinquency, ADHD-HI, and ODD measures after controlling for the SCT trait factor. In contrast, higher scores on the SCT trait factor significantly predicted (ps<.05) lower scores on the externalizing measures after controlling for the ADHD-IN trait factor (i.e., a double dissociation).

Internalizing symptom dimensions

Higher scores on the childhood SCT trait factor significantly (ps<.05) predicted higher scores on the withdrawal and anxiety/depression measures after controlling for childhood ADHD-IN trait factor whereas the reverse was not true. Neither the SCT or ADHD-IN trait factors showed a significant (ps>.05) unique relationship with somatic complaints.

Social functioning dimensions

Higher scores on the SCT trait factor significantly (p<.001) predicted greater shyness after controlling for the ADHD-IN trait factor whereas the ADHD-IN trait did not uniquely predict shyness. Higher scores on the ADHD-IN and SCT trait factors both uniquely predicted (p<.05) greater social impairment.

Parent perception of academic impairment

Higher scores on the SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors both uniquely predicted (ps<.05) higher levels of parent perception of math impairment while only higher scores on the ADHD-IN trait factor uniquely predicted (p<.001) parental perception of adolescent impairment in reading.

Reading achievement

Higher scores on the SCT trait factor significantly predicted (ps<.05) lower scores on the four reading measures even after controlling for the ADHD-IN trait factor. In contrast, higher scores on the ADHD-IN trait factor only uniquely predicted (p<.05) lower scores on WJ Reading Fluency.

Mathematics achievement

Only higher scores on the ADHD-IN trait factor uniquely predicted (ps<.05) lower scores on the three measures of mathematics achievement.

Processing speed and working memory

Only higher scores on the ADHD-IN trait factor uniquely predicted (ps<.001) lower scores on the Coding and Symbol Search measures of processing speed. Neither the SCT nor the ADHD-IN trait factor uniquely predicted scores on the Digit Span measure of working memory.2

Discussion

This study examined whether trait SCT in early childhood was associated with functioning in adolescence and, moreover, whether SCT and ADHD-IN trait factors in early childhood demonstrated independent and unique associations with adolescent functioning. This study, covering a 10-year period from preschool to the end of ninth grade, is by far the longest developmental span examined in studies evaluating the longitudinal outcomes associated with SCT, either in isolation or as differentiated from ADHD-IN.

The first key finding is that both SCT and ADHD-IN contained more trait variance than occasion-specific variance in early childhood. In addition, trait variance increased as children progressed from preschool through early elementary school. The mean trait variance for SCT and ADHD-IN (65% and 61%, respectively) across four measurement occasions in this study was very similar to two other studies that examined trait variance for SCT and ADHD-IN (69% for both factors) as well as ODD symptoms (67%) and callous-unemotional traits (64%) in Spanish children across three occasions over a 12-month period starting in the spring of first grade (Litson et al., 2016; Preszler, Burns, Litson, Geiser, & Servera, 2017; Preszler, Burns, Litson, Geiser, Servera, et al., 2017; Seijas et al., 2017). Thus, particularly once children are in formal schooling, both SCT and ADHD-IN are largely trait-like to a degree similar to some other psychopathologies. This finding casts doubt on the suggestion that SCT may primarily represent a fluctuating state caused by poor sleep (Fallone et al., 2005) and, indeed, SCT has now been shown in two studies to be as much trait-like as ADHD-IN. Nevertheless, both SCT and ADHD-IN have some degree of state variance, and improving sleep reduces both SCT and ADHD-IN symptoms (Becker et al., 2018; Garner et al., 2017). More research is needed to understand the trait and state nature of SCT, including whether certain aspects of SCT are more state-like than others and perhaps more receptive to intervention.

After isolating the trait variance of SCT and ADHD-IN from preschool through second grade, we examined whether these trait factors were not only correlated with but also differential predictors of functioning at the end of ninth grade. SCT and ADHD-IN are themselves strongly correlated (Becker et al., 2016). And yet, as has been repeatedly shown in cross-sectional studies and in a handful of short-term longitudinal studies, SCT and ADHD-IN have different external correlates when considered simultaneously (Becker & Barkley, 2018). We found the correlation between the trait ADHD-IN and trait SCT factors to be .66, indicating that these factors shared 44% of their true score variance. Further, the findings of the current study – from the longest prospective sample to date – provide the clearest evidence yet that SCT and ADHD-IN often part ways when it comes to the functional outcomes they predict. These findings can be summarized as follows: (1) SCT significantly predicted greater withdrawal and anxiety/depression whereas ADHD-IN did not uniquely predict these internalizing domains; (2) ADHD-IN uniquely predicted more externalizing behaviors whereas SCT uniquely predicted fewer externalizing behaviors; (3) SCT uniquely predicted shyness whereas both SCT and ADHD-IN uniquely predicted global social difficulties; and (4) ADHD-IN uniquely predicted poorer math achievement and slower processing speed whereas SCT more consistently predicted poorer reading achievement. Thus, the pattern of findings is one whereby the SCT attentional problem characterized in part by internal distractibility (e.g., excessive daydreaming) predicts subsequent internalizing psychopathology and withdrawn/shy behaviors whereas the ADHD-IN attentional problem characterized in part by external distractibility (e.g., extraneous stimuli) predicts subsequent externalizing psychopathology and behaviors. Although this is an oversimplification of the complexities of information processing and attention regulation difficulties, as well as their associations with functional outcomes, this possibility warrants empirical scrutiny with laboratory-based measures of mind wandering that can distinguish between internal and external distractors (Smallwood & Schooler, 2015). The separation of SCT and ADHD-IN in their relations to internalizing and externalizing psychopathologies also points to the value of examining SCT and ADHD-IN within hierarchical models of psychopathology, particularly as findings from such efforts may situate SCT within a theoretical framework and guide hypotheses for future work (Becker & Willcutt, 2018).

Our academic achievement findings indicate that both SCT and ADHD-IN are uniquely associated with poorer reading on timed fluency tests, and SCT is also uniquely associated with poorer reading performance on untimed tests that assess basic word identification and passage comprehension. It is noteworthy that the WJ Passage Comprehension subtest has a strong decoding component (Keenan et al., 2008), as do word identification skills, suggesting that SCT may have a more negative impact than ADHD-IN for decoding specifically. In contrast, our findings indicate that ADHD-IN has a more negative impact than SCT on mathematics achievement, including both timed and untimed math tasks. The link between ADHD-IN and poorer math achievement may be due to increased careless errors, especially in the face of possible working memory deficits (Antonini et al., 2016). Similarly, we found ADHD-IN but not SCT to be uniquely associated with slower processing speed, a finding that echoes some (Bauermeister et al., 2012; Wood et al., 2017) but not all (Jacobson et al., 2018; Tamm et al., 2018; Willcutt et al., 2014) previous cross-sectional research. In any event, SCT has not been consistently linked to slower processing speed, which raises the issue of what precisely is the “sluggish cognitive” nature of SCT. It would be advantageous for future studies to consider developmental differences in the possible link between SCT and processing speed (Jacobson et al., 2018), to employ multiple processing speed measures with varying degrees of complexity (Cepeda et al., 2013), and to examine processing speed under different conditions (e.g., high memory load). There is also preliminary evidence that SCT may be associated with slower motor speed (Hinshaw et al., 2002) and early selective attention deficits (Huang-Pollock et al., 2005), as well as parent ratings of children’s punishment (vs. reward) sensitivity (Becker et al., 2013), none of which were measured in the current study but nonetheless warrant further investigation.

Limitations and future directions

Findings should be considered in light of study strengths and limitations. Our use of a large sample representative of the state of Colorado bolsters confidence in the generalizability of the study findings. Still, all longitudinal studies examining SCT have relied on community/school-based samples, with no studies examining whether SCT predicts later functioning in clinical samples of youth or youth recruited based on elevated SCT specifically. In addition, our sample was primarily White and well-educated. It is thus unclear whether our findings will generalize to clinical samples or samples that are more racially and socio-economically diverse. In addition, the SCT items used in this study do not capture the full breadth of SCT symptomatology, though we have added confidence in our SCT symptom set given that it includes both the slowed/sleepy and inconsistent alertness aspects of SCT and our findings largely replicate previous cross-sectional research (Becker et al., 2016). Nevertheless, additional studies with well-validated measures of SCT would be informative for replicating and extending our findings. For example, studies using measures with more items tapping performance speed/mental confusion may be better poised to examine whether, and under what conditions, SCT is associated with processing speed. Although a strength of our study was the inclusion of parent ratings, academic achievement testing, and neuropsychological performance as outcome domains, it would be beneficial for future studies to incorporate other methods such as additional measures of academic and neuropsychological performance, along with teacher ratings (particularly for academic functioning) and youth self-report (particularly for internalizing symptoms). Indeed, the lack of adolescent self-report of internalizing symptoms is a significant limitation of the current study. It would also be informative for future studies to examine the overlap of children with clinically elevated SCT and/or ADHD, estimated to co-occur in 40–60% of cases (Barkley, 2013) and in 25–40% of participants in the current study (see Table 1), in longitudinal designs to examine the stability of elevations and their co-occurrence and correspondence with functional outcomes.

Conclusions

Findings of a prospective study spanning a ten-year period provide the strongest longitudinal evidence so far that SCT is more trait- than state-like and also uniquely associated with important developmental outcomes including withdrawal/shyness, internalizing symptoms, and lower reading achievement. These results provide strong support for the validity of SCT, the discriminant validity of SCT and ADHD-IN, and the importance of including SCT in broader models of attentional problems in youth.

Supplementary Material

Key points.

Sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) is distinct from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder inattention (ADHD-IN) and concurrently associated with poorer functioning, though few longitudinal studies have been conducted.

SCT and ADHD-IN similarly contained more trait variance than occasion-specific variance in early childhood, with trait variance increasing as children progressed from preschool through second grade.

In regression analyses predicting functioning at the end of ninth grade, SCT significantly predicted greater withdrawal and anxiety/depression whereas ADHD-IN did not uniquely predict these internalizing domains. ADHD-IN uniquely predicted more externalizing behaviors whereas SCT uniquely predicted fewer externalizing behaviors.

SCT uniquely predicted shyness whereas both SCT and ADHD-IN uniquely predicted global social difficulties at the end of ninth grade.

ADHD-IN uniquely predicted poorer math achievement and slower processing speed whereas SCT more consistently predicted poorer reading achievement at the end of ninth grade.

Findings of the current study – from the longest prospective sample to date – provide the clearest evidence yet that SCT and ADHD-IN often part ways when it comes to the functional outcomes they predict.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (R01HD38526 and R01HD68728). The authors were also supported in part during the preparation of this manuscript by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K23MH108603 (SPB), F31HD091967 (DRL), and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants P50HD27802 and R24HD75460 (EGW). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

DR. STEPHEN P. BECKER (Orcid ID : 0000-0001-9046-5183)

MR. DANIEL LEOPOLD (Orcid ID : 0000-0001-7250-9998)

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Descriptive information on study measures.

Appendix S1. Additional description of study measures.

Appendix S2. Single source-two construct latent state-trait model with autoregressive coefficients.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

For descriptive purposes, we examined the percentage of children with elevated SCT and/or ADHD-IN symptoms (defined as >2SD above the mean) at the second grade timepoint, since this timepoint is when SCT and ADHD-IN demonstrated the greatest trait variance. 5.67% of children met the threshold for elevated SCT symptoms (but not elevated ADHD-IN symptoms), 2.78% met the threshold for elevated ADHD-IN symptoms (but not elevated SCT symptoms), and 1.89% met the threshold for both SCT and ADHD symptoms (see Table 1). We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

All the regression analyses were repeated with child sex, mother education (years), and father education (years) as separate control variables. All the significant and non-significant results in Table 2 remained the same with one exception: SCT’s unique association with CLDQ Math was only marginally significant, p = .07. All the regression analyses were repeated again with child sex, mother education (years), father education (years), and an estimate of pre-kindergarten IQ (mean of vocabulary and block design subtests) as four control variables. All the significant and non-significant results in Table 2 remained the same with these exceptions: (1) SCT was no longer uniquely related to parent-rated anxiety/depression, CLDQ math skills, and WJ word identification; and (2) ADHD-IN was no longer uniquely related to WJ calculations. In addition, to confirm that SCT symptoms are not a proxy of IQ, we examined correlations of SCT and ADHD-IN with estimated IQ (average of WPPSI-R Vocabulary and Block Design subtests). Both trait SCT and trait ADHD-IN were significantly associated with lower IQ (rs = -.23 and -.27, respectively), with Mplus model constraint procedure indicating that the magnitude of the correlation was stronger for ADHD-IN (p < .001).

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Antonini TN, Kingery KM, Narad ME, Langberg JM, Tamm L, & Epstein JN. (2016). Neurocognitive and behavioral predictors of math performance in children with and without ADHD. J Atten Disord , 20(2), 108-118. doi: 10.1177/1087054713504620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. (2013). Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from ADHD in children and adolescents: Executive functioning, impairment, and comorbidity. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol , 42(2), 161-173. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.734259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo (concentration deficit disorder?): current status, future directions, and a plea to change the name. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 42(1), 117-125. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9824-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, & Murphy KR. (1998). Atention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A clinical workbook. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JJ, Barkley RA, Bauermeister JA, Martinez JV, & McBurnett K. (2012). Validity of the sluggish cognitive tempo, inattention, and hyperactivity symptom dimensions: neuropsychological and psychosocial correlates. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 40(5), 683-697. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9602-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP. (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo and peer functioning in school-aged children: a six-month longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res , 217(1–2), 72-78. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP. (2017). "For some reason I find it hard to work quickly": Introduction to the Special Issue on sluggish cognitive tempo. J Atten Disord , 21(8), 615-622. doi: 10.1177/1087054717692882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, & Barkley RA. (2018). Sluggish cognitive tempo In Banaschewski T, Coghill D. & Zuddas A. (Eds.), Oxford textbook of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (pp. 147-153). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Epstein JN, Tamm L, Tilford AA, Tischner CM, Isaacson PA, . . . Beebe DW. (2018). Shortened sleep duration causes sleepiness, inattention, and oppositionality in adolescents with ADHD: Findings from a crossover sleep restriction/extension study. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Fite PJ, Garner AA, Greening L, Stoppelbein L, & Luebbe AM. (2013). Reward and punishment sensitivity are differentially associated with ADHD and sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms in children. Journal of Research in Personality , 47(6), 719-727. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Garner AA, Tamm L, Antonini TN, & Epstein JN. (2017). Honing in on the social difficulties associated with sluggish cognitive tempo in children: Withdrawal, peer ignoring, and low engagement. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2017.1286595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, & Langberg JM. (2013). Sluggish cognitive tempo among young adolescents with ADHD: relations to mental health, academic, and social functioning. J Atten Disord , 17(8), 681-689. doi: 10.1177/1087054711435411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Leopold DR, Burns GL, Jarrett MA, Langberg JM, Marshall SA, . . . Willcutt EG. (2016). The internal, external, and diagnostic validity of sluggish cognitive tempo: A meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry , 55(3), 163-178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, Luebbe AM, Fite PJ, Stoppelbein L, & Greening L. (2014). Sluggish cognitive tempo in psychiatrically hospitalized children: Factor structure and relations to internalizing symptoms, social problems, and observed behavioral dysregulation. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 42(1), 49-62. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9719-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SP, & Willcutt EG. (2018). Advancing the study of sluggish cognitive tempo via DSM, RDoC, and hierarchical models of psychopathology. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-1136-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmar M, Servera M, Becker SP, & Burns GL. (2017). Validity of sluggish cognitive tempo in South America: An initial examination using mother and teacher ratings of Chilean children. J Atten Disord , 21, 667-672. doi: 10.1177/1087054715597470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernad MD, Servera M, Becker SP, & Burns GL. (2016). Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD inattention as predictors of externalizing, internalizing, and impairment domains: A 2-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 44(4), 771-785. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0066-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson CL, & Mann M. (2002). Sluggish cognitive tempo predicts a different pattern of impairment in the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, predominantly inattentive type. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol , 31(1), 123-129. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda NJ, Blackwell KA, & Munakata Y. (2013). Speed isn't everything: complex processing speed measures mask individual differences and developmental changes in executive control. Dev Sci , 16(2), 269-286. doi: 10.1111/desc.12024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher ME, Hulslander J, Byrne B, Samuelsson S, Keenan JM, Pennington B, . . . Olson RK. (2015). Genetic and environmental etiologies of the longitudinal relations between prereading skills and reading. Child Dev , 86(2), 342-361. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallone G, Acebo C, Seifer R, & Carskadon MA. (2005). Experimental restriction of sleep opportunity in children: effects on teacher ratings. Sleep , 28(12), 1561-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender C, Krafft CE, & Schweitzer JB. (2015). Differentiating SCT and inattentive symptoms in ADHD using fMRI measures of cognitive control. Neuroimage Clin , 8, 390-397. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner AA, Hansen A, Baxley C, Becker SP, Sidol CA, & Beebe DW. (2017). Effect of sleep extension on sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms and driving behavior in adolescents with chronic short sleep. Sleep Med , 30, 93-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser C, Hintz FA, Burns GL, & Servera M. (2017). Latent variable modeling of person-situation data In Rauthmann JF, Sherman R. & Funder DC. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Psychological Situations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman CA, Willcutt EG, Rhee SH, & Pennington BF. (2004). The relation between sluggish cognitive tempo and DSM-IV ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 32(5), 491-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Carte ET, Sami N, Treuting JJ, & Zupan BA. (2002). Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: II. Neuropsychological performance in relation to subtypes and individual classification. J Consult Clin Psychol , 70(5), 1099-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang-Pollock CL, Nigg JT, & Carr TH. (2005). Deficient attention is hard to find: applying the perceptual load model of selective attention to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder subtypes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry , 46(11), 1211-1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson LA, Geist M, & Mahone EM. (2018). Sluggish cognitive tempo, processing speed, and internalizing symptoms: The moderating effect of age. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 46(1), 127-135. doi: 10.1007/s10802-017-0281-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan JM, Betjemann RS, & Olson RK. (2008). Reading comprehension tests vary in the skills they assess: Differential dependence on decoding and oral comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading , 12(3), 281-300. doi: 10.1080/10888430802132279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khadka G, Burns GL, & Becker SP. (2016). Internal and external validity of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD inattention dimensions with teacher ratings of Nepali children. J Psychopathol Behav Assess , 38(3), 433-442. doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9534-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Burns GL, Beauchaine TP, & Becker SP. (2016). Bifactor latent structure of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)/oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms and first-order latent structure of sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms. Psychol Assess , 28(8), 917-928. doi: 10.1037/pas0000232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Burns GL, & Becker SP. (2017). Can sluggish cognitive tempo be distinguished from ADHD inattention in very young children? Evidence from a sample of Korean preschool children. J Atten Disord , 21, 623-631. doi: 10.1177/1087054716680077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Burns GL, & Becker SP. (2018). Toward establishing the transcultural validity of sluggish cognitive tempo: Evidence from a sample of South Korean children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol , 47, 61-68. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1144192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Burns GL, Snell J, & McBurnett K. (2014). Validity of the sluggish cognitive tempo symptom dimension in children: Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-inattention as distinct symptom dimensions. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 42(1), 7-19. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9714-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DR, Christopher ME, Burns GL, Becker SP, Olson RK, & Willcutt EG. (2016). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sluggish cognitive tempo throughout childhood: Temporal invariance and stability from preschool through ninth grade. J Child Psychol Psychiatry , 57(9), 1066-1074. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litson K, Geiser C, Burns GL, & Servera M. (2016). Trait and state variance in multi-informant assessments of ADHD and academic impairment in Spanish first-grade children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol, 1-14. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1118693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, & Schoemann AM. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn't be one. Psychol Methods , 18(3), 285-300. doi: 10.1037/a0033266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SA, Evans SW, Eiraldi RB, Becker SP, & Power TJ. (2014). Social and academic impairment in youth with ADHD, predominately inattentive type and sluggish cognitive tempo. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 42(1), 77-90. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9758-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurnett K, Villodas M, Burns GL, Hinshaw SP, Beaulieu A, & Pfiffner LJ. (2014). Structure and validity of sluggish cognitive tempo using an expanded item pool in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 42(1), 37-48. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9801-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew KS, & Woodcock RW. (2001). Technical Manual: Woodcock-Johnson III. Itasca, IL: Riverside. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (Eigth ed). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Penny AM, Waschbusch DA, Klein RM, Corkum P, & Eskes G. (2009). Developing a measure of sluggish cognitive tempo for children: content validity, factor structure, and reliability. Psychol Assess , 21(3), 380-389. doi: 10.1037/a0016600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preszler J, Burns GL, Litson K, Geiser C, & Servera M. (2017). Trait and state variance in oppositional defiant disorder symptoms: A multi-source investigation with Spanish children. Psychol Assess , 29(2), 135-147. doi: 10.1037/pas0000313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preszler J, Burns GL, Litson K, Geiser C, Servera M, & Becker SP. (2017). How consistent is sluggish cognitive tempo across occasions, sources, and settings? Evidence from latent state-trait modeling. Assessment, 1073191116686178. doi: 10.1177/1073191116686178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seijas R, Servera M, García-Banda G, Barry CT, & Burns GL. (2017). Evaluation of a four-item DSM-5 limited prosocial emotions specifier scale within and across settings with Spanish children. Psychol Assess. doi: 10.1037/pas0000496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servera M, Bernad MD, Carrillo JM, Collado S, & Burns GL. (2016). Longitudinal correlates of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-inattention symptom dimensions with Spanish children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol , 45, 632-641. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1004680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood J, & Schooler JW. (2015). The science of mind wandering: empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annu Rev Psychol , 66, 487-518. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZR, & Langberg JM. (2017). Predicting academic impairment and internalizing psychopathology using a multidimensional framework of sluggish cognitive tempo with parent- and adolescent reports. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry , 26(9), 1141-1150. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1003-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm L, Brenner SB, Bamberger ME, & Becker SP. (2018). Are sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms associated with executive functioning in preschoolers? Child Neuropsychol , 24(1), 82-105. doi: 10.1080/09297049.2016.1225707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamm L, Garner AA, Loren RE, Epstein JN, Vaughn AJ, Ciesielski HA, & Becker SP. (2016). Slow sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms are associated with poorer academic performance in children with ADHD. Psychiatry Res , 242, 251-259. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.05.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen J, Wagner R, & Rashotte CA. (1999). A Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Wåhlstedt C, & Bohlin G. (2010). DSM-IV-defined inattention and sluggish cognitive tempo: independent and interactive relations to neuropsychological factors and comorbidity. Child Neuropsychol , 16(4), 350-365. doi: 10.1080/09297041003671176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1974). Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1991). Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Boada R, Riddle MW, Chhabildas N, DeFries JC, & Pennington BF. (2011). Colorado Learning Difficulties Questionnaire: Validation of a parent-report screening measure. Psychol Assess , 23(3), 778-791. doi: 10.1037/a0023290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Chhabildas N, Kinnear M, DeFries JC, Olson RK, Leopold DR, . . . Pennington BF. (2014). The internal and external validity of sluggish cognitive tempo and its relation with DSM-IV ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol , 42(1), 21-35. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9800-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood WL, Potts HE, Lewandowski LJ, & Lovett BJ. (2017). Sluggish cognitive tempo and speed of performance. J Atten Disord , 21, 684-690. doi: 10.1177/1087054716666322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.